Abstract

The correlation between insomnia and visual impairment has not been extensively studied. This study aims to investigate this relationship among individuals aged 45 and above in India. This investigation utilized data from the 2017–2018 Wave 1 of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI). Visual impairment was self-reported, including presbyopia, cataracts, glaucoma, myopia, and hyperopia. Insomnia symptoms were determined by at least one of the following: difficulty in initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty in maintaining sleep (DMS), or early morning awakening (EMA) occurring three or more times per week. Analytical methods involved multivariate logistic regression, subgroup analyses, and interaction tests to interpret the data. In our cohort of 65,840 participants, 29.6% reporting insomnia symptoms demonstrated a higher risk for visual impairment. There was a significant association between visual impairment and increased risk of insomnia symptoms after adjustment for confounders. Furthermore, age in the relationship between insomnia and cataracts, sex in the relationship between insomnia and myopia, and age, sex, and smoking status in the relationship between insomnia and hyperopia, was found to have a significant interaction effect, respectively. Visual impairment was significantly associated with a higher incidence of insomnia among middle-aged and older adults in India. These findings underscore the importance of timely interventions to improve sleep quality and overall well-being in visually impaired populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Visual impairment (VI) is an increasingly prevalent health concern globally, particularly among older adults who naturally experience declines in health, physical, and cognitive functions1. Worldwide, around 36 million individuals are affected by blindness, over 217 million experience moderate to severe visual impairment, another 188 million have mild visual impairment, and an additional 667 million people aged 45 and above suffer from visual impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia2. The leading causes of significant vision loss among adults aged 45 and over are cataracts, refractive errors, and glaucoma3. Recent research suggests that visual impairment may significantly increase the risk of mortality4, mental health conditions such as depression5 and anxiety6, cognitive decline7,8,9, and dementia10. This association also extends to greater utilization of healthcare services and higher medical expenditures11.

Insomnia is recognized when an individual persistently struggles with sleep initiation, maintenance, or premature awakening, accompanied by daytime dysfunction, even with ample opportunity to sleep. Affecting 10–20% of the global population, with half enduring chronic insomnia, it presents at least three times weekly for over 3 months12. This condition is marked by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity, leading to significant distress or functional impairment, and cannot be attributed to other disorders or substance use13. Surveys in India indicate insomnia prevalence of around 15% among older adults in urban West Bengal, and a Bangalore study found a 13% occurrence in elderly participants14. In South India, 36% of patients with insomnia symptoms reported difficulties with sleep onset and maintenance, while 7.9% experienced early morning awakenings15. Insomnia also coexists with various other health issues, including psychological distress, cognitive impairment, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic syndrome, and contributes to substantial medical and occupational expenses, both direct and indirect16,17,18,19.

Visual impairment can lead to disturbances in the circadian rhythm20 and exacerbate neuropsychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression, ultimately impairing central nervous system functionality and contributing to the development of insomnia21. Existing research underscores the negative impact of visual impairment on sleep patterns. Studies conducted in Russia found that individuals with visual impairment had more than twice the odds of reporting insomnia symptoms compared to those without, with this association remaining significant even after adjusting for factors such as age and gender21. This finding further confirms the link between visual dysfunction and sleep disturbances. Community research in the U.S. suggested that older adults with visual impairment are more likely to experience various sleep issues, such as difficulty falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, early morning awakenings, and daytime sleepiness22. Additionally, such individuals often report increased disrupted sleep patterns and a higher prevalence of sleep/wake disturbances23. Although several studies have addressed the association between visual impairment and insomnia, these investigations are often confined to specific ethnic cohorts23,24,25. We are the first to study the association between visual impairment and insomnia among middle-aged and older people in India. Our study identifies the prevalence of insomnia and visual impairment among those aged 45 and older in India and explores the correlation between self-reported visual impairment and insomnia, using baseline data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). We hypothesize the occurrence of insomnia symptoms is more prevalent in individuals with visual impairment compared to those without such impairments.

Methods

Data

The data for our analysis were sourced from the first wave of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), conducted between 2017 and 201826. LASI included 73,408 individuals aged 45 and above, and their spouses, spanning all Indian states and union territories, barring Sikkim. LASI is principally geared towards examining the health and socioeconomic facets of aging. Employing a multi-stage stratified area probability clustering sampling design, the survey extracted comprehensive individual, household, and community details. This study specifically utilized the Harmonized LASI dataset after excluding entries with incomplete data on visual impairment, insomnia symptoms, or covariates, resulting in an analytic sample size of 65,840 (Fig. 1). Ethical clearances for LASI were secured from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and all partner entities. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. Further methodological specifics and microdata are detailed in the Harmonized LASI documentation27.

Visual impairment

Visual impairment was determined through self-reported histories of treatment or surgery for specific eye conditions, including cataracts, glaucoma, myopia, and hyperopia.

Insomnia symptoms

Insomnia was assessed by the presence of symptoms including difficulties with sleep initiation, maintenance, or premature morning awakenings. Symptom frequency was categorized as: never/rarely (0–2 times weekly), occasionally (3–4 times weekly), or frequently (5+ times weekly). Participants reporting at least one symptom occurring frequently were classified as experiencing insomnia symptoms. Accordingly, frequent reports of trouble falling asleep were indicative of difficulty in initiating sleep (DIS), trouble staying asleep or resuming sleep after waking was considered difficulty in maintaining sleep (DMS), and premature awakenings were classified as early morning awakening (EMA).

Covariates

Covariates known to influence visual impairment were included in the analysis. Gender was classified as male or female. Age was recorded in years. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Marital status was categorized as married/partnered or other. The intensity of physical activity was assessed by frequency. Family income was measured in rupees. We also accounted for chronic diseases based on self-reported medical diagnoses, including hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, heart disease, and thyroid disease. Self-rated health (SRH) was rated from excellent to poor. Drinking and smoking status were recorded as yes or no. The residential setting was categorized as rural or urban. To address missing covariate data, we employed multivariate imputation using predictive mean matching.

Statistical analysis

In the baseline characteristics, continuous variables were presented using mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were presented by frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to derive p-values, chosen for its non-reliance on data normality and homogeneity of variances, enhancing its suitability. The chi-square test was utilized for categorical variables, and where expected frequencies were less than 10, Fisher’s exact test was applied.

Initially, we categorized insomnia symptoms as a categorical variable and divided participants into groups with and without symptoms. Employing multivariate logistic regression, we investigated associations between five different visual impairment and insomnia symptoms, while controlling for various covariates to mitigate confounding influences. Model I entailed no adjustments; Model II adjusted for age, gender, and BMI; and Model III further adjusted for drinking, smoking, SRH, and vigorous physical activity, economic situation, marital status, place of residence, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, thyroid disease. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software, with a p-value threshold of < 0.05 denoting significance.

To evaluate the heterogeneity in the relationship between insomnia and visual impairment across different covariates (including age, sex, smoking status, and drinking status), we conducted interaction analyses. Stratified logistic regression models were employed for the subgroup analyses, and the p-values for interaction were obtained using the log-likelihood ratio test to compare models with and without the inclusion of covariate interactions. All statistical analyses in this study were performed using R software, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The characteristics of participants stratified by insomnia symptoms are presented in Table 1. Among 65,840 participants, females were more likely to report insomnia symptoms (62.8% female vs. 37.2% male). The average weighted age of participants was 57.7 years (SD = 11.5). A total of 19,462 (29.6%) reported insomnia symptoms. These participants tended to be older, have a lower BMI, be unmarried, suffer from chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, heart disease, and thyroid disease, exhibit signs of depression, report poorer self-rated health, engage in less vigorous physical activity, currently smoke, and reside in rural areas. Moreover, as shown in Table 1, a greater prevalence of visual impairment, including presbyopia, cataracts, glaucoma, myopia, and hyperopia, was observed in those with insomnia symptoms compared to those without.

Association between Insomnia symptoms and visual impairment

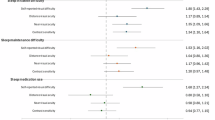

The multivariate logistic regression analysis detailed in Table 2 explores the link between insomnia symptoms and visual impairment. Initially, the unadjusted model (Model 1) established significant associations (Cataracts: OR 1.59 [1.51–1.67]; Presbyopia: OR 1.49 [1.40–1.58]; Glaucoma: OR 1.83 [1.63–2.06]; Myopia: OR 1.28 [1.23–1.33]; Hyperopia: OR 1.34 [1.29–1.39]). Subsequent adjustment for age, gender, and BMI (Model 2) maintained these associations as significant (Cataracts: OR 1.32 [1.25–1.39]; Presbyopia: OR 1.41 [1.32–1.50]; Glaucoma: OR 1.67 [1.48–1.87]; Myopia: OR 1.29 [1.24–1.34]; Hyperopia: OR 1.32 [1.26–1.37]). Adding environmental covariates (Model 3), including drinking, smoking status, self-rated health, vigorous physical activity, marital status, education level, and place of residence, still showed significant associations (Cataracts: OR 1.25 [1.18–1.32]; Presbyopia: OR 1.37 [1.29–1.46]; Glaucoma: OR 1.55 [1.38–1.75]; Myopia: OR 1.32 [1.27–1.38]; Hyperopia: OR 1.31 [1.26–1.37]). The fully adjusted model (Model 4), which incorporated additional biological covariates, continued to demonstrate significant relationships (Cataracts: OR 1.22 [1.15–1.29]; Presbyopia: OR 1.34 [1.26–1.43]; Glaucoma: OR 1.52 [1.34–1.71]; Myopia: OR 1.29 [1.24–1.34]; Hyperopia: OR 1.28 [1.23–1.33]).

Subgroup analysis

To further assess the relationship between different types of visual impairment and insomnia symptoms, we conducted heterogeneity analyses across various subgroups. The results are presented in Table 3. Our samples were stratified by age categories, sex, drinking status, and smoking status. Overall, the ORs in each subgroup were consistent with the main association results, indicating a positive association between visual impairment and insomnia symptoms. Interaction tests revealed that age significantly influences the relationship between insomnia and cataracts, sex significantly influences the relationship between insomnia and myopia, and age, sex, and smoking status significantly influence the relationship between insomnia and hyperopia.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, the size and proportion of the middle-aged and older population in India have changed dramatically, which have gradually increased, from 24.71 million (5.6%) in 1961 to 104 million (8.6%) in 201128. India’s aging population has become a major concern for policy makers, researchers, and other stakeholders. Insomnia remains one of the most common sleep disorders in the middle-aged and older population. Older adults are more likely to suffer from the medical and psychiatric effects of insomnia29. Our study demonstrated up to 30% of the middle-aged and older population reporting insomnia symptoms, which was consistent with the previous study30 but apparently higher than the another studies conducted in india14. Women, older adults, people with socioeconomic hardship, patients with coexisting medical disorders or poor self-rated physical health are more vulnerable to insomnia31. We identified that the middle-aged and older population who drunk alcohol had a lower incidence of insomnia than those who did not. Conversely, Britton et al.32 found that men maintaining a heavy volume of drinking or having an unstable consumption pattern tended to have worse sleep profiles. Perhaps because the latter study included only men. Additionally, of the several visual impairments, the prevalence of uncorrected refractive errors (myopia or hyperopia) was the highest, followed by cataracts, and glaucoma was the lowest. Compared with previous data, there was no change in the prevalence of refractive errors but a significant reduction in cataracts, reflecting the positive effect of eye care services (cataracts surgery)1,33.

Our study demonstrated that visual impairment was significantly associated with insomnia. A previous cross-sectional study revealed that visual impairment in college students was associated with short sleep duration23. A study conducted by Lanzani et al.34 reported that nighttime sleep efficiency was significantly decreased, and mean wake episodes during the night was significantly increased in patients with glaucoma. Our results indicated that visually impaired individuals were more likely to suffer from insomnia than those without visual impairment, regardless of age, gender, and other confounding factors.

It has been shown that the occurrence of insomnia is closely associated with visual loss or inhibited light perception (LP)35. Approximately 55–70% of totally blind individuals (those lacking LP) experience desynchronized circadian rhythms with accompanying sleep disturbances36. A community-based study found that visual impairment may affect sleep in older adults by limiting daily activities or reducing light exposure22. Thus, older adults with visual impairment may need brighter lighting for circadian movement. Work by Lucassen and colleagues further suggested that high light intensity prevented the decrease in vasopressin(AVP)-expressing neurons in the senescent suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is considered to be the principal component of the biological clock in the brain37. Recently, Zhou et al.38 established cortical adenosine signaling as the neurochemical basis responsible for the sleep-inducing effects of 40 Hz light flickering, providing a novel, promising, and non-invasive approach to insomnia treatment.

Furthermore, there may be a connection between glaucoma and sleep disturbances mediated by changes in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Previous research indicated that degeneration in RGCs can disrupt the pathways that transmit light signals essential for regulating circadian rhythms, potentially contributing to sleep issues39,40. Specifically, ipRGCs, a subtype of RGCs sensitive to blue light, play a key role in aligning the circadian rhythm41. Dysfunction in ipRGCs can reduce melatonin production, which is vital for sleep regulation, thus leading to increased risk of insomnia or disrupted sleep patterns in individuals with glaucoma41. These findings suggest that considering non-image-forming visual functions may be important when addressing sleep problems in visually impaired populations. Supporting circadian alignment through approaches like bright light therapy or melatonin supplementation could be beneficial for those with glaucoma-related sleep disturbances.

While refractive errors such as myopia and hyperopia generally do not directly impair circadian rhythms, their association with insomnia may be explained by indirect factors. Uncorrected refractive errors can lead to symptoms such as eye strain, headaches, and visual discomfort, which may contribute to stress and negative affect, ultimately impacting sleep quality42. Furthermore, individuals with uncorrected refractive errors may experience increased daytime fatigue, leading to napping during the day and potentially disrupting their sleep-wake cycle, thereby increasing the risk of insomnia. These factors may help explain the observed association between refractive errors and insomnia in our study. Future research is needed to investigate the underlying mechanisms linking refractive errors and insomnia.

Our study has several limitations. First, the self-reported data on visual impairment may be affected by reporting errors, including recall bias and subjective interpretations. Second, the cause-and-effect relationship between various ophthalmic diseases and insomnia may not be accurately recognized due to the cross-sectional design of this study; subsequent prospective and intervention studies may offer a more comprehensive explanation. Third, although we adjusted for multiple covariates, we did not specifically exclude participants with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is known to have a strong association with glaucoma risk. Future studies should consider OSA screening to better isolate the effects of visual impairment on sleep disturbances. Finally, the influence of uncontrolled covariates cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Our study identified a significant association between visual impairment and insomnia among middle-aged and older adults in India, underscoring the importance of timely sleep assessments and interventions for individuals with visual impairments. Early detection and management of insomnia symptoms could improve patients’ quality of life and reduce healthcare burdens. Additionally, these findings can guide healthcare policymakers and clinicians in developing comprehensive health strategies to provide holistic care for individuals with visual impairments. Future prospective studies are needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms of this association and to evaluate the efficacy of targeted interventions in promoting overall health and well-being in this population.

Data availability

All data were from the public database (https://lasi-india.org); no ethical approval was needed.

References

Pascolini, D. & Mariotti, S. P. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 96, 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 (2012).

Collaborators, G. B. a. V. I. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 9, e130–e143. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30425-3 (2021).

Dandona, L. & Dandona, R. What is the global burden of visual impairment? BMC Med. 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-4-6 (2006).

Zhang, X. et al. Association between dual sensory impairment and risk of mortality: a cohort study from the UK Biobank. BMC Geriatr. 22, 631. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03322-x (2022).

Um, Y. J. et al. Association of changes in sleep duration and quality with incidence of depression: a cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 328, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.031 (2023).

Genario, R. et al. Sleep quality is a predictor of muscle mass, strength, quality of life, anxiety and depression in older adults with obesity. Sci. Rep. 13, 11256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37921-4 (2023).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868 (2013).

Fischer, M. E. et al. Age-related sensory impairments and risk of cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1981–1987. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14308 (2016).

Maharani, A., Dawes, P., Nazroo, J., Tampubolon, G. & Pendleton, N. Associations between Self-reported sensory impairment and risk of Cognitive decline and impairment in the Health and Retirement Study Cohort. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 75, 1230–1242. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz043 (2020).

Hwang, P. H. et al. Longitudinal changes in hearing and visual impairments and risk of dementia in older adults in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2210734. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10734 (2022).

Ding, Y. et al. Association of sensory impairment with healthcare use and costs among middle-aged and older adults in China. Public. Health 206, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.02.012 (2022).

Gulia, K. K. & Kumar, V. M. Sleep disorders in the elderly: a growing challenge. Psychogeriatrics 18, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12319 (2018).

Wittchen, H. U. et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 (2011).

Muhammad, T., Gharge, S. & Meher, T. The associations of BMI, chronic conditions and lifestyle factors with insomnia symptoms among older adults in India. PLoS One 17, e0274684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274684 (2022).

Panda, S. et al. Sleep-related disorders among a healthy population in South India. Neurol. India 60, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.93601 (2012).

Suzuki, E. et al. Sleep duration, sleep quality and cardiovascular disease mortality among the elderly: a population-based cohort study. Prev. Med. 49, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.016 (2009).

Shi, L. et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 40, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.010 (2018).

Zhai, L., Zhang, H. & Zhang, D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress. Anxiety 32, 664–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22386 (2015).

Depner, C. M., Stothard, E. R. & Wright, K. P. Jr. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr. Diab Rep. 14, 507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-014-0507-z (2014).

Lawrenson, J. G., Hull, C. C. & Downie, L. E. The effect of blue-light blocking spectacle lenses on visual performance, macular health and the sleep-wake cycle: a systematic review of the literature. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 37, 644–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12406 (2017).

Seixas, A. et al. Relationship between visual impairment, insomnia, anxiety/depressive symptoms among Russian immigrants. J. Sleep. Med. Disord 1, 569 (2014).

Zizi, F. et al. Sleep complaints and visual impairment among older americans: a community-based study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 57, M691–694. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/57.10.m691 (2002).

Ghemrawi, R. et al. Association between visual impairment and sleep duration in college students: a study conducted in UAE and Lebanon. J. Am. Coll. Health 71, 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1888738 (2023).

Ingram, D. G. et al. Sleep challenges and interventions in children with visual impairment. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 59, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.3928/01913913-20210623-01 (2022).

Peltzer, K. & Phaswana-Mafuya, N. Association between visual impairment and low vision and sleep duration and quality among older adults in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070811 (2017).

Chien, S. et al. 3. The Gateway to Global Aging Data. Produced and distributed by the University of Southern California with funding from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG042778, 2R01 AG030153, 2R01 AG051125). https://doi.org/10.25549/h-lasi (2023).

Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18, India Report. In International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai (2020).

Census of India. Office of the Registrar General & census commissioner, New Delhi 2013 (2011).

Patel, D., Steinberg, J. & Patel, P. Insomnia in the elderly: a review. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 14, 1017–1024. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7172 (2018).

Foley, D. J. et al. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep 18, 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/18.6.425 (1995).

Morin, C. M. & Jarrin, D. C. Epidemiology of Insomnia: prevalence, course, risk factors, and Public Health Burden. Sleep. Med. Clin. 17, 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.03.003 (2022).

Britton, A., Fat, L. N. & Neligan, A. The association between alcohol consumption and sleep disorders among older people in the general population. Sci. Rep. 10, 5275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62227-0 (2020).

Blindness, G. B. D., Vision Impairment, C. & Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to Sight: an analysis for the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health. 9, e144–e160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7 (2021).

Lanzani, M. F. et al. Alterations of locomotor activity rhythm and sleep parameters in patients with advanced glaucoma. Chronobiol. Int. 29, 911–919. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.691146 (2012).

Skene, D. J., Lockley, S. W., Thapan, K. & Arendt, J. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 39, 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1051/rnd:19990302 (1999).

Emens, J. S. & Eastman, C. I. Diagnosis and treatment of Non-24-h sleep-wake disorder in the Blind. Drugs 77, 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0707-3 (2017).

Lucassen, P. J., Hofman, M. A. & Swaab, D. F. Increased light intensity prevents the age related loss of vasopressin-expressing neurons in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. 693, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(95)00933-h (1995).

Zhou, X. et al. 40 hz light flickering promotes sleep through cortical adenosine signaling. Cell. Res. 34, 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-023-00920-1 (2024).

Turner, P. L. & Mainster, M. A. Circadian photoreception: ageing and the eye’s important role in systemic health. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 92, 1439–1444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2008.141747 (2008).

Sozen-Delil, F. I., Comba, O. B. & Ucar, G. Evaluation of insomnia effect on ganglion cell complex, middle retina, and choroid. Int. Ophthalmol. 44, 381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-024-03303-6 (2024).

Reutrakul, S. et al. Relationship between intrinsically photosensitive ganglion cell function and circadian regulation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 10, 1560. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58205-1 (2020).

Lücke, A. J. et al. Good night-good day? Bidirectional links of daily sleep quality with negative affect and stress reactivity in old age. Psychol. Aging 37, 876–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000704 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This analysis uses data or information from the Harmonized LASI dataset and Codebook, Version A.3 as of April 2023, developed by the Gateway to Global Aging Data (DOI: https://doi.org/10.25549/h-lasi). The development of the Harmonized LASI was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG042778, 2R01 AG030153, 2R01 AG051125). For more information about the Harmonization project, please refer to https://g2aging.org/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by X.C and Y.Z. The first draft of the manuscript was written by X.C and Y.Z, and the manuscript was critically revised by M.L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Zhu, Y. & Luo, M. The relationship between visual impairment and insomnia among people middle-aged and older in India. Sci Rep 14, 30261 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82125-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82125-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive functions in elderly patients with insomnia: a case-control study

Middle East Current Psychiatry (2026)

-

Association between visual impairment and sleep quality: A cross-sectional, comparative study of severity, eye conditions, and risk factors

Eye (2026)

-

The impact of visual and hearing impairments on the risk of arthritis among middle-aged and older Chinese adults (2011–2015): the mediating role of depressive symptoms

BMC Public Health (2025)