Abstract

As a result of human activities, surface waters worldwide are experiencing increasing levels of eutrophication, leading to more frequent occurrences of microalgae, including harmful algal blooms. We aimed to investigate the impact of decomposing camelina straw on mixed phytoplankton communities from eutrophic water bodies, comparing it to the effects of barley straw. The research was carried out in 15 aquaria (five of each type – containing no straw, camelina straw, and barley straw). The experiment lasted eight weeks, and the water used in the aquaria was sourced from an eutrophic reservoir. Our research revealed that the camelina straw had the most significant inhibitory effect on the growth of specific groups and species of phytoplankton (especially chrysophytes, potentially toxic cyanobacteria, and dinoflagellates). This inhibition was achieved by releasing polyphenols, primarily gallic and caffeic acids and flavonoids. Simultaneously, polyphenols promoted the growth of filamentous green algae. Our findings present novel data on the vulnerability of freshwater species and taxonomic groups of algae to the effects of camelina and barley straw exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Standing-water ecosystems, such as shallow lakes and ponds, are highly susceptible to eutrophication and degradation primarily due to their easily exploited natural characteristics. Eutrophication, resulting from excessive nutrient loadings from human activities and worsened by climate changes, is currently the primary global concern in these aquatic ecosystems1,2.

Human-induced eutrophication of ponds and lakes significantly affects their functioning and the organisms that live in them. Hypoxia, the disappearance of submerged macrophytes, biodiversity loss, and algae blooms are the primary consequences of a gradual rise in water fertility3. Consequently, persistent and regular occurrences of water blooms result in an ecological imbalance in aquatic ecosystems. The rapid proliferation of phytoplankton, particularly cyanobacteria, as well as chlorophytes and cryptophytes, is further exacerbated by global warming4,5due to the preference of these groups for elevated water temperatures. Furthermore, climate change exacerbates the potential danger of toxic cyanobacteria in aquatic systems6. Elevated temperatures stimulate microalgae growth, specifically cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (cyanoHABs)7.

To address eutrophication and algal blooms and enhance the ecological condition and water quality of lakes and ponds, it is imperative to initially decrease the influx of nutrients from the surrounding area into the waterbody8. Furthermore, restoration interventions are frequently required to mitigate the excessive proliferation of phytoplankton.

Reclamation methods should be affordable, user-friendly, productive, and sustainable. That entails avoiding harm to aquatic flora and fauna9.

These methods include introducing straws of certain plant species into the water ecosystems. The most popular is barley straw, a recognized and effective approach for restoring lakes, ponds, and dammed rivers by controlling algal growth10. Barley straw decomposition releases allelopathic substances, primarily phenolic compounds, which can potentially hinder the growth of specific phytoplankton species11. The algaecides are produced through the microbial breakdown of lignin in the straw tissues, carried out by fungi in well-oxygenated water12. Most studies focus on the impact of barley straw on particular taxonomic groups of algae10or only examine specific taxa13,14. Although waterbody restoration efforts have become more common and extensive, there is still limited understanding of the impact of straw on phytoplankton communities. That includes not only the overall abundance of algae and the abundance of different taxonomic groups but also the densities of dominant species and the qualitative composition of the communities.

In addition, based on our initial laboratory findings (unpublished data), it has been observed that camelina straw has the potential to impede the growth of algae. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no existing literature on this topic. Our research aims to compare the impact of camelina and barley straw on algal development, considering both physico-chemical and microbiological factors. The study’s primary objectives were to determine whether camelina and barley straw similarly reduce species richness and inhibit microalgal growth during nutrient inflow, including potentially toxic cyanobacteria species. Additionally, the study aimed to identify which type of decomposing straw is more effective in restraining algae growth. Thus, we conducted experiments on phytoplankton communities from an eutrophic reservoir composed of representatives of different taxonomical groups of algae.

The research hypotheses were: (1) Straw derived from Camelina sativa and Hordeum vulgare plants will release distinct allelopathic compounds, namely polyphenols and flavonoids, in varying quantities. These compounds will impact the taxonomic groups and species of algae present. (2) As the straw from both plant species decomposes, the diversity of phytoplankton species will decrease. (3) The straw from each plant species will selectively inhibit or stimulate the growth of specific taxonomic groups of algae, resulting in a noticeable shift in their dominance within algal communities. (4) The response of dominant algae taxa to camelina and barley straw will be specific to each species. (5) Camelina and barley straw will significantly alter the water’s physico-chemical and microbiological properties, influencing algal growth and shaping the structure of phytoplankton communities in distinct ways.

Materials and methods

In September 2022, water samples were collected from the surface layers of Rusałka Lake in the pelagic zone. The lake is in the Wielkopolska Province, Western Poland, at 52°25’30.2’’N 16°52’56.9’’E. The samples were taken for phycological, microbiological, and physico-chemical analyses. Lake Rusałka is a shallow and heavily enriched urban reservoir. The concentration of nutrients accumulated in previous years, combined with a low N: P ratio, frequently triggers vigorous growth of cyanobacteria between June and November15. The field measurements included the determination of water temperature (19.12 °C), pH (7.20), and oxygenation (17.10%). Samples were collected using vessels calibrated to hold 1 L of water for quantitative analysis and a plankton net with a mesh size of 25 μm for qualitative analysis to study phytoplankton. The collected samples were then preserved using Lugol solution.

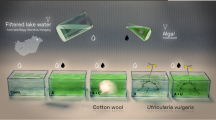

We obtained a 15-liter sample of bottom sediments and a 345-liter sample of surface water from the lake for use in the microcosm experiments (Fig. 1). The sediments were meticulously blended in the laboratory, partitioned into identical sub-samples, and allocated into 15 glass aquaria containing 1 L of sediments for the experiment. Every aquarium was filled with 23 L of lake water and equipped with a 6500 K, 900 lumens cold light source programmed to operate for 14 h. The aquaria were categorized into three groups: five with 20 g of barley straw, five with 20 g of camelina straw, and five without any straw as a control. The water was continuously aerated to optimize the conditions for the decomposition of straw. The aquaria have been stored for eight weeks in a room with a consistently maintained temperature of approximately 20 °C. This temperature closely resembled the conditions observed in Rusałka Lake when collecting water for the experiments.

From September 20, 2022, to November 15, 2022, samples were collected every week from each aquarium for phycological analysis (0.5 L), microbiological analysis (60 ml), and chemical analysis (450 ml). 2 ml of nutrients were added to the aquaria after each sampling starting from the second week of the experiment. These nutrients included 0.2 mg P-PO4 dm−3 and 1 mg N-NO3 + N-NH4 dm−3, which were added in equal amounts. This addition of nutrients replaced the natural inflow of nutrients from the catchment areas in aquatic ecosystems that are affected by human activities. The experimental design of our study sought to replicate freshwater environments experiencing eutrophication. Observations were made on the growth of macrophytes in aquaria, and the percentage of vegetation coverage was measured for each aquarium.

Based on the collected samples, temporal variations in phytoplankton have been detected for eight weeks. Each water sample (120 in total) was consistently preserved using Lugol solution for phycological analyses. The samples were subjected to sedimentation in the laboratory, followed by concentration to a volume of 5 mL, and finally preserved using formalin. Phytoplankton taxa were identified using a light microscope at 200x, 400x, and 1000x magnifications. The sediment samples were processed in the laboratory and concentrated to a volume of 5 ml for quantitative analysis. The abundance of phytoplankton was determined by enumerating the number of individuals present in a minimum of 300 fields of a Fuchs-Rosenthal chamber (height: 0.2 mm, area: 0.0625 mm2; Brand GmbH + CO KG in Wertheim, Germany). Single cells and algae cenobia were considered as one individual. For blue-green algae colonies, such as Aphanocapsa and Microcystis, each colony with an area of 400 µm2was considered one individual. In the case of trichomes, a segment of 100 μm length was considered as one individual. The dominant taxa were determined to constitute 10% or greater of the overall phytoplankton abundance in each sample. The classification of microalgae taxa names and concepts was based on the classifications provided in Algaebase16.

The Hanna HI 9828 multi-parameter meter (MERA Sp. z o. o., Warsaw, Poland) was used to measure various parameters, including pH, oxygenation (%), electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), formazin nephelometric units (FNU), and water temperature (oC). The measurement was conducted on each occasion when the samples were collected. The VEA (visual expansion of algae) index was determined through visual estimation, considering the proportion of the aquarium volume occupied by the spatial structures of macroalgae (%).

Nitrogen and phosphorus

Water samples to determine the nutrient content were taken into three test tubes as mixed samples – 50 ml from each aquarium containing (1) camelina straw (250 ml in total), (2) barley straw (250 ml in total), and (3) control (250 ml in total). The total N in H2O samples was determined using the Kjeldahl method. In the initial stage, the sample was mineralized with H2SO4 and a catalyst at a temperature of 350oC for 90 min. Then, after cooling and adding NaOH, the sample was distilled. In the last step, the ammonium form was combined with HCl and titrated with a standard NaOH solution in the presence of a Tashiro indicator.

After their prior mineralization, total P was determined in a Mars 6 microwave mineralizer (CEM Corporation, Matthews, USA) in water samples by adding H2O2. Then, P was determined by atomic emission spectrometry with microwave N and the Agilent 4210 MP-AES device (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA).

TNB

The following procedure determined the total bacteria count (TNB). The volume of a single sample for analysis was 10 ml water. Initially, 10 ml of the test material from each test was suspended in 90 mL of the diluting fluid (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Then, tenfold dilutions were made from the prepared suspensions in the diluting fluid. Inoculations were performed up to 20 min from the preparation of the solutions. To this end, 1 mL of the suspension from the two dilutions of each sample was transferred with a sterile pipette to sterile Petri dishes (two for each dilution). Then, they were flooded with 15 mL of agar medium (BTL nutrient agar, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at 45oC. The prepared Petri dishes were incubated in aerobic conditions and placed flat in an incubator at 30 ± 1oC for 72 h. After incubation, the bacterial colonies on all Petri dishes were counted, and based on the number of colonies counted, the total number of bacteria in 1 g of test material was obtained (CFU g−1). The result was the mean and was expressed as log CFU g−1.

TNM

The number of molds and yeasts per 1 g of water was assessed according to the test procedure using the standard decimal dilution dish method – PN-ISO 21527-2: 2009. The diluted method was used: 1 g of sample was put in 10 mL of sterile distilled water and mixed with the magnetic stirrer for 2 min. Next, 1 mL of suspension was carried on potato-dextrose agar medium (BTL, Łódź, Poland) in Petri dishes and spread on the medium surface with a sterile glass stick. The Petri dishes were incubated at 25oC for seven days.

Phenolic acids and flavonoids

The obtained water samples were analyzed for the content of total phenolic compounds, total phenolic acids, and total flavonoids using a modified spectrophotometric method adapted to liquid chromatography conditions. The total polyphenol content was tested using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. A sample (40 µL) of the dissolved mixture in 1 mL of Me/H2O (1:1, v/v) was added to 3 mL of distilled water and 200 µL of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and mixed. The mixture was shaken and allowed to stand for 6 min, then 600 µL of a sodium carbonate solution was added and shaken to mix. The solutions were left at 20 °C for two hours. The samples were then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter.

Total bioactive compounds were analyzed using an Acquity UPLC liquid chromatography (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a Waters Acquity PDA detector (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) on an Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 column (100 mm x 2.1 mm, particle size 1.7 μm) (Waters, Dublin, Ireland) at a 320 nm wavelength for total phenolic acids, 765 nm wavelength for total phenolic compounds, and 624 nm wavelength for total flavonoids, relative to the blind test. The sample injection volume was 10 µL, and the flow rate was 0.4 mL min−1. The isocratic elution was performed using a mobile phase, a mixture of A: 0.1% formic acid solution in acetonitrile and B: 0.1% aqueous formic acid solution17. The peak areas were summed to determine the total polyphenol content.

The total phenolic acid content in the water (three replicates per treatment) was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per gram (mg GAE g−1) compared with the caffeic acid calibration curve. The calibration curve range was 10–1000 mg L−1 (r2 = 0.9982). The total flavonoid extract content (three replicates per treatment) was expressed as mg rutin equivalents per gram (mg RUTE g−1) compared with the rutin calibration curve. The calibration curve range was 10–1000 mg L−1 (r2 = 0.9871). Each commercial compound standard was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses and models were based on discriminant analysis. The analyses showed which variables – phenolic acids, flavonoids derived from camelina or barley straw biomass decomposition, and environmental parameters – may affect reducing taxonomic groups and phytoplankton species in water. The model was constructed using canonical variate analysis (CVA) – the canonical variation of Fisher’s linear discriminant analysis (LDA)18. The borderline significance level was determined with the Monte Carlo permutation test (number of permutations: 9.999).

The Canoco 5 for Windows package and the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (accessed October 3, 2019) were used for all comparisons, calculations, and graphic elements. In addition, the following tools from Canoco for Windows were used: Canoco for Windows 4.5, CanoDraw for Windows, and WCanoImp (Microcomputer Power, New York, USA). A one-way analysis of variance was used to determine statistical differences between types of aquaria in terms of the studied variables (one-way ANOVA).

Results

The taxonomic diversity of phytoplankton communities

A total of 151 phytoplankton taxa belonging to eight taxonomic groups were identified. The groups with the highest number of taxa were Chlorophyta (chlorophytes) – 63 taxa, Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) – 30 taxa, and Cyanobacteria – 25 taxa. By contrast, the Euglenophyta (euglenoids), Cryptophyceae (cryptophytes), Dinophyceae (dinoflagellates), Tribophyceae (tribophytes), and Chrysophyceae (chrysophytes) were in smaller numbers, with 14, 7, 5, 4, and 3 taxa, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). In the control group, which did not have any straw, including the initial sample taken directly from the lake, we observed the highest number of different taxa (120) in the water throughout the entire research period. In comparison, the aquaria with camelina straw had 113 taxa, and the aquaria with barley straw had only 94 phytoplankton taxa. The aquaria without straw (Fig. 2) contained the greatest diversity of cyanobacteria (22 taxa) and diatoms (26 taxa). Nevertheless, the camelina straw aquaria exhibited the most significant number of chlorophytes and euglenoid taxa, with 54 and 11 taxa, respectively. The study also identified phytoplankton species that occur only in specific types of aquaria, including 25 in control, 15 in the aquaria containing camelina straw, and nine in the aquaria containing barley straw (Supplementary Table S2).

Temporal variations in the relative abundance of different algal taxonomic groups in the phytoplankton communities of the studied microcosms

During the initial phase of the experiment, the control group exhibited the highest mean phytoplankton abundance. Starting on October 18, 2022, the significant decrease in the total phytoplankton abundance in the control sample can be explained by high oxygenation and higher pH (Table 1; Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S6), which was thoroughly explained in the discussion section, while water samples taken from aquaria containing camelina and barley straw showed increased phytoplankton abundance compared to previous observations. The increase in the total number of algae individuals in straw primarily occurred due to the significant prevalence, or even dominance, of filamentous green algae. With their shorter filaments, these algae unintentionally entered phytoplankton communities as tychoplankton organisms (originally periphyton organisms) (Figs. 3 and 4).

Temporal distribution of the share of different phytoplankton groups among the total algal abundance in three types of aquaria (CYA – Cyanobacteria; fCHL – filamentous Chlorophyta, n-CHL – non-filamentous, coccal Chlorophyta; EUG – Euglenophyta, BAC – Bacillariophyceae; CHR – Chrysophyceae; TRI – Tribophyceae; DIN – Dinophyceae; CRY – Cryptophyceae).

Temporal changes in the distribution of different taxonomic groups of algae were observed. Specifically, there was a noticeable decline in the proportion of cyanobacteria in the total phytoplankton. This decrease was observed just two weeks after the experiment was initiated in all types of aquaria (Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables S8–S10). Subsequently, alterations in the proportion of distinct phytoplankton taxonomic groups were noted in the aquaria. The control was primarily dominated by chrysophytes, with a maximum abundance of 6297.8 ind. mL−1. Initially, diatoms were the predominant organisms in the aquaria containing camelina straw (maximum 1058.40 ind. mL−1). Following those, filamentous green algae became the most abundant (reaching a maximum of 2448.8 ind. mL−1), and that dominance continued until the last week of the study. The most significant differences in the share of phytoplankton groups were observed in water collected from aquaria with barley straw. In the first three dates, the dominance of mainly chrysophytes was observed (up to a maximum of 769 ind. mL−1). In the following four dates, green algae dominated (a maximum of 2158.2 ind. mL−1), and on the last date, chrysophytes reappeared (3517.6 ind. mL−1).

The phytoplankton taxonomic groups and dominating taxa respond to the polyphenols and physicochemical parameters of water

The study found significant correlations between the gallic and caffeic acid concentration in water and decreased abundance of chrysophytes, cyanobacteria, and dinoflagellates (Supplementary Table S4). Furthermore, a positive correlation was established between increases in filamentous green algae and the concentration of the phenolic acids mentioned above. The abundance of phytoplankton groups exhibited significant variations between control aquaria (where the prevalence of chrysophytes was highly correlated) and aquaria containing camelina (Fig. 5).

CCA model describing the impact of polyphenols and flavonoids on phytoplankton groups in three types of aquaria (CYA – Cyanobacteria; fCHL – filamentous Chlorophyta, n-CHL – non-filamentous, coccal Chlorophyta; EUG – Euglenophyta, BAC – Bacillariophyceae; CHR – Chrysophyceae; TRI – Tribophyceae; DIN – Dinophyceae; CRY – Cryptophyceae).

The O2 content in the water had a negative correlation with most phytoplankton groups (diatoms, cryptophytes, tribophytes, cyanobacteria, and euglenoids), indicating that high O2 concentration could limit the growth of these algae groups (Fig. 6). An analogous correlation was observed between pH and FNU. However, the degree of association was significantly weaker (Supplementary Table S5). A positive relationship was found between the nitrogen concentration in water and the presence of green algae and dinoflagellates. The EC exhibited a positive correlation with both cyanobacteria and euglenoids. The distribution of vectors signifies significantly contrasting environmental conditions in control aquaria as opposed to aquaria containing camelina straw. The model was not affected by variations in water temperature, as the observed differences were not statistically significant.

CCA model describing the impact of environmental variables on phytoplankton groups in three types of aquaria (CYA – Cyanobacteria; fCHL – filamentous Chlorophyta, n-CHL – non-filamentous, coccal Chlorophyta; EUG – Euglenophyta, BAC – Bacillariophyceae; CHR – Chrysophyceae; TRI – Tribophyceae; DIN – Dinophyceae; CRY – Cryptophyceae).

The water collected from camelina aquaria exhibited elevated levels of phenolic acids and flavonoids, as indicated in the model depicted in Fig. 7; Table 1, and Supplementary Table S7. Phenolic acids (mainly gallic and caffeic) were primarily associated with representatives of filamentous chlorophytes (Oedogonium sp. 1, Oedogonium sp. 2, Uronema confervicolum, and Mougeotia sp.) and with some taxa belonging to non-filamentous chlorophytes (e.g., Carteria sp., Scenedesmus ecornis, Tetradesmus lagerheimii, Characium angustum, Desmodesmus communis, and Desmodesmus opoliensis), as well as could act antagonistically towards most taxa of dominant cyanobacteria (Chroococcus sp., Cuspidothrix issatschenkoi, Hyella sp., Planktothrix agardhii) and cryptophytes (e.g., Cryptomonas erosa, Cryptomonas marssonii, Cyanomonas acuta) marked in the research (Supplementary Table S3). The most neutral taxonomic group turned out to be diatoms, whose species formed a compact group in the central point of the model (Fig. 7).

CCA model describing the influence of polyphenols and flavonoids on different phytoplankton dominating taxa in three types of aquaria (Chsp – Chroococcus sp.; Hysp – Hyella sp.; Ossp – Oscillatoria sp.; Plag – Planktothrix agardhii; Cuis – Cuspidothrix issatschenkoi; Caco – Carteria coccifera; Casp – Carteria sp.; Chan – Characium angustum; Chgl – Chlamydomonas globosa; Chlsp – Chlamydomonas sp.; Deco – Desmodesmus communis; Mosp – Mougeotia sp.; Osp1 – Oedogonium sp. 1; Osp2 – Oedogonium sp. 2; Tela – Tetradesmus lagerheimii; Scec – Scenedesmus ecornis; Deop – Desmodesmus opoliensis; Teca – Tetraedron caudatum; Urco – Uronema confervicolum; Stco – Staurosira construens; Frcr – Fragilaria crotonensis; Frin – Fragilaria intermedia; Nami – Navicula minima; Niac – Nitzschia acicularis; Nipa – Nitzschia palea; Ulac – Ulnaria acus; Ulul – Ulnaria ulna; Chrsp – Chromulina sp.; Cyac – Cyanomonas acuta; Crer – Cryptomonas erosa; Crma – Cryptomonas marssonii; Rhte – Rhodomonas tenuis).

Microbiological and physicochemical conditions and total phytoplankton abundance in the studied aquaria

The experiment’s observation revealed that, despite identical conditions set up for all aquaria, different types of straw impacted alterations in environmental parameters, including both physico-chemical and biological factors. The control group exhibited higher pH levels and oxygenation compared to the aquaria containing camelina and barley straw, as indicated in Table 1. The observed differences were statistically significant, as confirmed by Anova analysis.

By examining temporal fluctuations in these variables, it can be inferred that the water’s pH levels and oxygen concentration gradually increased in all aquarium types. The water taken from the aquarium with barley straw exhibited the most notable variations in these parameters. Simultaneously, the control aquaria exhibited relatively elevated values on the initial date (excluding sample 0) for water parameters, with an average pH of 8.17 and an average O2 level of 46.20% (Supplementary Table S6). The pH value of the sample taken from the lake (sample 0) was 7.2, while the O2 content was 17.10%.

When barley and camelina straw were used in the aquaria, lower levels of total molds and bacteria were observed compared to the control group. The temporal variations of these parameters were characterized by distinct irregularity. Significant correlations were observed in aquaria containing camelina straw. They exhibited the most significant proportion of macroscopic structure-forming algae, specifically filamentous green algae, as indicated by the highest recorded value of the VEA index. On the fourth study date, macroscopic algae structures were observed in all aquaria. The growth rate of macroscopic algae was highest in camelina aquaria, reaching an average VEA index value of 80% at the end of the study (Supplementary Table S6).

Water collected from aquaria with barley straw had the highest average values for specific electrolytic conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), and turbidity (FNU), and these differences were statistically significant. The experiment’s ambient temperature was regulated using air conditioning. Consequently, no notable disparities were observed in the water temperatures among the various types of aquaria tested. However, fluctuations in temperature were evident within the aquaria on different dates, which may be attributed to varying levels of solar exposure in the room. The straw-containing aquaria exhibited the greatest average abundance of algae, primarily due to the prevalence of green algae in camelina straw and a combination of green algae and chrysophytes in barley straw. However, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The camelina aquarium had the lowest average N concentration levels in the collected water. No significant statistical differences were observed in the P content of the water.

Table 1 shows that the water collected from aquaria where camelina straw decomposed had the highest phenolic acids and flavonoids concentrations. Gallic and caffeic acids had the highest average values, measuring 2.89 and 1.99 mg L−1, respectively. The temporal changes indicate an apparent increase in the concentration of these acids in water collected from aquaria containing camelina and barley straw over time. That suggests the acids are released into the water as the straw decomposes (Supplementary Table S7). The concentrations of 2, 4-; 2, 5-; and 2, 6-hydroxybenzoic acids ranged from 0 to 0.47 mg L−1, with slight variations. An analogous correlation was noted for shikimic acid, with an amplitude ranging from 0 to 0.29. Camelina aquaria exhibited elevated levels of flavonoids in the analysis. Significant disparities were statistically observed in catechin, naringenin, and quercetin levels. For naringenin, the values were insignificant and did not surpass 0.45 mg L−1. The concentration of all phenolic acids and flavonoids tested in water collected from aquaria with straw increased over time. The highest rate of increase was observed for gallic and caffeic acid in aquaria with camelina straw.

Discussion

In line with our predictions, camelina and barley straw impacted the structure of phytoplankton communities in the studied microcosms differently (Fig. 8). That influence was evident in the number of phytoplankton taxa, total abundance, and the abundance of the particular taxonomic groups and dominating species.

Our research revealed that barley straw was the most efficient in reducing the total number of taxa (Supplementary Table S1) and the number of exclusive species (Supplementary Table S2). Meanwhile, aquaria containing camelina straw had more representatives of chlorophytes and euglenoids (which prefer high organic contents) than aquaria with barley straw or no straw (Fig. 2). That indicates that camelina straw positively impacts the diversity of these algae groups. By contrast, conditions lacking straw appeared more conducive to the number of cyanobacterial and diatom species. Moreover, chlorophytes, diatoms, and cyanobacteria had the highest number of representatives/taxa in all three types of aquaria (Fig. 2) compared to the remaining taxonomic groups of algae, which is characteristic of eutrophic water bodies19. The predominance of representatives of these groups resulted from the fact that the water for the study was collected from a lake with high nutrient levels, but also from the fact that during the investigation, a regular supply of nutrients in constant concentrations was provided in all aquaria to replicate the trophic conditions found in eutrophic lakes and ponds affected by ongoing human activities. The selection of appropriate phytoplankton communities (with species composition characteristic of eutrophic water bodies) for this type of experimental research is crucial because it is precisely the water bodies with a high trophic state and with species preferring such conditions that require the most reclamation treatments due to excessive phytoplankton development (especially cyanobacteria). Regrettably, the available research lacks sufficient data on the impact of decomposing straw on phytoplankton species composition. Most studies (e.g10,14). , prioritize analyzing quantitative structure while neglecting the biodiversity aspect. However, investigating the influence of straw on changes in species composition in eutrophic reservoirs is vital because these changes will, in turn, result in potential substantial changes in the food webs of aquatic ecosystems in the future.

In the case of the total phytoplankton abundance in investigated microcosms, temporal changes in each type of aquaria were observed, but also between three types of aquaria (Fig. 3), which was mainly related to the direct effect of camelina and barley straw, but also to some physicochemical parameters of water (especially oxygenation). The decrease in the overall average number of phytoplankton abundance in aquaria with control resulted from the high oxygenation and pH (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S6), which reached the highest average values in these aquaria (Table 1). High and increasing concentrations of dissolved oxygen inhibited phytoplankton growth. Similar observations were made in other studies20,21 in artificial, microalgal culture systems with air saturation. According to Peng et al.22, the reduction of cell growth or even culture collapse at high concentrations of dissolved oxygen is caused by inhibiting photosynthesis because of photochemical damage to photosynthetic apparatus and other cellular components. In our experiments, the values of oxygen concentrations have increased at least twice as compared to the values noted in the lake, from which water for the aquaria was taken (Supplementary Table S6). An additional factor causing the decrease of the total phytoplankton abundance over time was the increase in pH value, especially in control (Supplementary Table S6), related to the increase in oxygenation. According to Kawecka & Eloranta23, the optimal pH range for most freshwater planktonic algal growth is 6.5–8.5. These values were exceeded in aquaria with straw, but only on the last two dates of the study, and they reached a value of approximately pH = 9 in the last week of the experiment. In the water reservoir from which water was collected for the aquaria, the pH was lower than that in the aquaria during the experiment in the laboratory and amounted to 7.2, which would suggest that this acidity level was optimal for the development of the algae species that occurred in the water we used. However, our statistical analysis showed that the inhibitory effect of changes in the pH of aquarium water on the abundance of phytoplankton and most taxonomic groups was not as significant as the effect of oxygenation (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table S5). The lower pH in the aquaria with straws (compared to the control) could be caused by the release of phenolic acids from the decomposing straw.

The decrease in the overall average number of phytoplankton individuals in aquaria with straw (especially with barley straw) compared to the number in aquaria with control, observed in the first three weeks of the experiment (Fig. 3), suggests an inhibitory effect of straw on planktonic algae at that time, which was confirmed by statistical analyses. The fourth week of research found an opposite tendency: the average abundance values in aquaria with straws were higher than in control. That was only due to a significant increase in the number and share of filamentous green algae (Fig. 4). Their short trichomes accidentally fell into phytoplankton communities, becoming part of them as tychoplankton organisms (originally periphytic), which broke away from compact large structures. They significantly enriched phytoplankton communities until the sixth week of the study, increasing their total abundance. Subsequently, in aquaria with straw, it was recorded that filamentous green algae were replaced mainly by cryptophytes and planktonic chlorophytes (in aquaria with camelina straw) and by planktonic chlorophytes and chrysophytes (in aquaria with barley straw). Thus, our observations have shown that a large share of filamentous green algae does not have to persist long (Fig. 4). Fervier et al.10 stated that macrophytes even replaced filamentous chlorophytes during the experiments using barley straw after time. A similar scenario was entirely possible in the continuation of our investigations because, at the end of the experimental period, an occurrence of growing aquatic higher plants was noted. High concentration and nitrogen inflow favored the development of filamentous green algae (Fig. 6) but should also favor the growth of macrophytes, which will compete with filamentous green algae for nutrients.

When comparing the effects of camelina straw and barley straw on the growth of different algal groups and species, it was found that camelina straw had a more significant inhibiting effect on phytoplankton abundance (Figs. 5, 6 and 7). The decomposition of camelina straw substantially impacted the chrysophytes, cyanobacteria, and dinoflagellates, reducing their abundance (Fig. 6). Remarkably, during our investigations, this variety of straw released significantly greater levels of phenolic acids (primarily gallic and caffeic) than barley straw (Table 1, Supplementary Table S7). Over time, the concentration of these polyphenols increased, selectively acting on systematic groups of algae (Fig. 6). The growth of the three taxonomic algae groups was further exacerbated by additional chemical compounds released by camelina straw, particularly protocatechuic acid and two flavonoids (catechin and quercetin), whose concentrations also progressively increased (Supplementary Table S7). Curiously, barley straw did not emit 2, 5-hydroxybenzoic acid and kaempferol flavonoid.

Eladel et al.13 demonstrated that decomposed rice straw was also found to release gallic and caffeic acids, both of which have inhibiting effects on various cyanobacteria taxa (such as Anabaena sp., Microcystis aeruginosa, Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, Oscillatoria tenuis), chrysophytes (from the genera Dinobryon and Synura), and freshwater algae in general. The results were consistent with ours regarding the inhibitory impact on the same two phytoplankton groups (Fig. 5), even though the straw originates from a different plant. However, certain studies have indicated that rice straw can promote the growth of chlorophytes, such as Chlorella sp.13. For comparison, we discovered that barley straw has a comparable but less potent impact on planktonic chlorophytes (Fig. 5).

Comparing the results of our investigations on camelina straw with other studies regarding the influence of decomposing barley straw on algal growth, the inhibiting effect on cyanobacteria abundance was also found10, but it was a short-term effect. Similarly, some study results also stated the negative impact of barley straw on specific cyanobacteria taxa (Dolichospermum flos-aquae, Microcystis aeruginosa, and Microcystis sp.)24. However, according to Fervier et al.10, barley straw promoted diatom growth, which was not observed in our experiments (Fig. 7). In our experiment, a strong inhibitory effect on algae development was observed for camelina straw, and the impact of barley straw was comparably low (Figs. 6 and 7). Unfortunately, due to the lack of literature on the effect of camelina, we compare the results with data relating to the release of similar polyphenols by straw from other plant species and its impact on algal development.

We also found that camelina straw (mainly by releasing gallic and caffeic acids) strongly stimulated the growth of filamentous chlorophytes (representatives of the genera Oedogonium, Uronema, and Mougeotia), together with the nitrogen inflow and high temperature (Figs. 6, 3 and 7). Those green algae formed compact, macroscopic structures, and smaller threads accidentally found their way into phytoplankton communities (as a tychoplanktonic species). According to other research10, barley straw did not affect filamentous algae growth. On the contrary, Islami & Filizadeh24 stated that barley straw extract negatively affected the growth of some filamentous green algae taxa (Cladophora glomerata and Spirogyra sp.). In our study, the most considerable appearance of filamentous green algae in aquaria with camelina straw, compared to aquaria with barley straw and control, resulted in a decrease in nitrogen in aquaria with camelina straw, probably because filamentous green algae (together with planktonic green algae) intensively absorbed it. Filamentous chlorophytes compete with microalgae for nutrients and light, thus leading to a secondary effect on phytoplankton. That suggests these microalgae will suffer mainly from nutrient competition with green macroalgae in aquatic ecosystems when the share of filamentous chlorophytes increases.

We also found a positive effect of camelina straw (especially phenolic acid – gallic) not only on filamentous green algae (especially Oedogonium species) but also on small, single-celled chlorophyte Carteria sp. (Fig. 7). Most of the other dominating and non-filamentous, planktonic chlorophytes (e.g., Desmodesmus opoliensis, Scenedesmus ecornis, Tetraedron caudatum, Tetradesmus lagerheimii) were also, but weaker associated with gallic and protocatechuic acids and flavonoid catechin. However, many studies proved that barley straw inhibited small planktonic chlorophytes of the genera Ankistrodesmus, Chlorella, and Scenedesmus 11,14. The species of diatoms dominating in our experiment (especially Staurosira construens and Ulnaria acus) seemed indifferent to the effect of polyphenols and flavonoids. Our results align with those showing that diatoms seemed resistant to straw treatment25. In line with our findings relating to the lack of impact of camelina straw on some phytoplankton taxa, barley straw, in some cases, also does not affect selected phytoplankton species according to data from other researchers26.

The impact of polyphenols and flavonoids on other phytoplankton-dominating taxa was negative (Fig. 7). Notably, most of the dominating cyanobacteria (Planktothrix agardhii, Cuspidothrix issatschenkoi, Chroococcus sp., Hyella sp.), cryptophytes (Cryptomonas marssonii, C. erosa, Cyanomonas acuta) and some chrysophytes taxa (e.g., Chromulinasp.), where inhibited mainly by gallic, protocatechuic and caffeic acids. However, Molversmyr27 stated that the growth of bloom-forming cyanobacteria Planktothrix aghardii was stimulated by barley straw.

Some cyanobacteria taxa occurred in lake water (Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, Dolichospermum spiroides, Microcystis aeruginosa) or even dominated in aquaria (Planktothrix agardhii and Cuspidothrix issatschenkoi) in our study are known to be common species, often causing water blooms in eutrophic ecosystems (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). In addition, P. agardhii, C. issatschenkoi, D. flos-aquae, Limnothrix redekei, M. aeruginosa, Raphidiopsis raciborskii and representatives of the genera Dolichospermum and Oscillatoria can produce toxins (neuro-, hepato- and dermatotoxins) and pose a severe risk to human and animal health28,29, which further increases the importance of using camelina straw in the fight against cyanobacteria. Dominating P. agardhii is one of the most famous bloom-forming species in many shallow eutrophic lakes of temperate climate zone, especially in summertime when the temperatures are high30, typical for turbid mixed environments19. In contrast to algae from other taxonomic groups, cosmopolitan and ubiquitous cyanobacteria are particularly dangerous in large quantities. In addition, they are not eagerly eaten by filter feeders (e.g., zooplankton), so they have no natural enemies that could regulate their numbers31. Therefore, expanding knowledge about natural methods of limiting their development is essential. According to our results, camelina straw seems more effective in preventing their mass occurrence than the commonly used barley straw.

Surprisingly, in microcosms with camelina and barley straw, a lower total molds and bacteria value was noted than in aquaria without straw (Table 1). The low contribution of these organisms in water caused reduced competition with algae for nutrients, which excludes this biotic factor as potentially beneficial in the “fight” against excessive phytoplankton growth. Therefore, decomposing straw did not indirectly inhibit algal growth.

Conclusions

In conclusion, planktonic algae well reflect changes from experimental treatments using camelina and barley straw. They quickly respond to changing environmental conditions due to their short life cycles and rapid reproduction rate. Obtained results should expand knowledge about the new, biological, and effective methods (using camelina straw) of limiting their growth, especially of potentially toxic and filamentous cyanobacteria, which often cause harmful algal blooms in eutrophic shallow lakes and ponds and of chrysophytes, which also can be toxic. This study also includes meaningful species-specific responses and shifts in species dominance in mixed phytoplankton communities. In addition, the research provides an understanding of the reasons for the allelopathic effect of decomposing camelina straw on phytoplankton communities compared to barley straw. It has been shown that camelina straw secretes more types and significant amounts of polyphenols and flavonoids. Even if decomposing barley straw strongly reduced phytoplankton species richness, camelina straw was the best tool to inhibit the growth of the main phytoplankton groups and species.

From a long-term perspective, the positive effect of camelina straw on filamentous green algae will promote a shift from dominance by microalgae to filamentous macroalgae and later even to macrophytes as leading primary producers and consequently to clear-water state. Fortunately, compact structures of filamentous chlorophytes can be removed mechanically, so their excessive growth (especially in small home water reservoirs) does not seem as troublesome as the development of cyanobacteria or other microalgae groups. However, this research shows that the development of filamentous green algae does not have to be long-lasting.

Our results also show that good oxygenation is necessary for straw’s beneficial effects, enabling its decomposition and inhibiting algal growth. In practice, using camelina extract should be considered to avoid the need for artificial oxygenation necessary for straw decomposition in eutrophic waters. However, using this method in small reservoirs such as ponds or garden ponds will be easier.

The results of this paper should help develop new strategies to improve the quality and ecological condition of water reservoirs using camelina straw by inhibiting the excessive growth of some algae and, thus, the adverse effects of water blooms. In the future, it is worth expanding research on the impact of camelina straw on other potentially toxic species, especially from the group of cyanobacteria and chrysophytes. According to our results, replacing barley straw with camelina straw is worth considering, as it may provide a better effect in inhibiting the development of cyanobacteria that form long-lasting and frequent blooms in eutrophic ponds and lakes.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary files).

Change history

11 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96967-8

References

Chuai, X. et al. Effects of climatic changes and anthropogenic activities on lake eutrophication in different ecoregions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 9, 503–514 (2012).

Yan, Q. et al. Internal nutrient loading is a potential source of eutrophication in Shenzhen Bay, China. Ecol. Ind. 127, 107736 (2021).

Sinclair, J. S., Fraker, M. E., Hood, J. M., Reavie, E. D. & Ludsin, S. A. Eutrophication, water quality, and fisheries: a wicked management problem with insights from a century of change in Lake Erie. Ecol. Soc. 28, (2023).

Celewicz, S. & Gołdyn, B. Phytoplankton communities in temporary ponds under different climate scenarios. Sci. Rep. 11, 17969 (2021).

Tewari, K. A review of Climate Change Impact studies on Harmful Algal blooms. Phycology 2, 244–253 (2022).

Erratt, K. J., Creed, I. F., Lobb, D. A., Smol, J. P. & Trick, C. G. Climate change amplifies the risk of potentially toxigenic cyanobacteria. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 5240–5249 (2023).

Clark, J. M. et al. Satellite monitoring of cyanobacterial harmful algal bloom frequency in recreational waters and drinking water sources. Ecol. Ind. 80, 84–95 (2017).

Alhamarna, M. Z. & Tandyrak, R. Lakes Restoration approaches. Limnological Rev. 21, 105–118 (2021).

Gołdyn, R., Podsiadłowski, S., Dondajewska, R. & Kozak, A. The sustainable restoration of lakes—towards the challenges of the Water Framework Directive. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 14, 68–74 (2014).

Fervier, V. et al. Evaluating nutrient reduction, grazing and Barley Straw as measures against Algal Growth. Wetlands 40, 193–202 (2020).

Pęczuła, W. Influence of barley straw (Hordeum vulgare L.) extract on phytoplankton dominated by Scenedesmus species in laboratory conditions: the importance of the extraction duration. J. Appl. Phycol. 25, 661–665 (2013).

Newman, J. & Barrett, P. R. F. Control of Microcystis aeruginosa by decomposing barley straw. J. Aquat. Plant. Manage. 31, 203–206 (1993).

Eladel, H. M., Abd-Elhay, R. & Anees, D. Effect of Rice Straw Application on Water Quality and Microalgal Flora in Fish ponds. Egypt. J. Bot. 59, 171–184 (2019).

Nikitin, O., Kuzmin, N., Nasyrova, E., Gliakina, M. & Stepanova, N. The effects of barley straw extract on the microalgae growth. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 315, 042051 (2019).

Gołdyn, R. et al. Functioning of the Lake Rusałka ecosystem in Poznań (western Poland). Oceanological Hydrobiol. Stud. 39, (2010).

Guiry, M. D. & Guiry, G. M. AlgaeBase. Worldwide electronic publication, University of Galway. (2024). https://www.algaebase.org/

Wijngaard, H. H. & Brunton, N. The optimisation of solid–liquid extraction of antioxidants from apple pomace by response surface methodology. J. Food Eng. 96, 134–140 (2010).

Lepš, J. & Šmilauer, P. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data Using CANOCO (Cambridge University Press, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615146

Reynolds, C. S., Huszar, V., Kruk, C., Naselli-Flores, L. & Melo, S. Towards a functional classification of the freshwater phytoplankton. J. Plankton Res. 24, 417–428 (2002).

Kazbar, A. et al. Effect of dissolved oxygen concentration on microalgal culture in photobioreactors. Algal Res. 39, 101432 (2019).

López Muñoz, I. & Bernard, O. Modeling the influence of temperature, light intensity and oxygen concentration on Microalgal Growth Rate. Processes 9, 496 (2021).

Peng, L., Lan, C. Q. & Zhang, Z. Evolution, detrimental effects, and removal of oxygen in microalga cultures: a review. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. 32, 982–988 (2013).

Kawecka, B. & Eloranta, P. V. Zarys ekologii glonów wód słodkich i środowisk lądowych [Outline of Ecology of Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae] (Wydaw. Naukowe PWN, 1994).

Islami, H. R. & Filizadeh, Y. Use of barley straw to control nuisance freshwater algae. J. AWWA. 103, 111–118 (2011).

Ridge, I. & Pillinger, J. M. Towards understanding the nature of algal inhibitors from barley straw. Hydrobiologia 340, 301–305 (1996).

Brownlee, E. F., Sellner, S. G. & Sellner, K. G. Effects of barley straw (Hordeum vulgare) on freshwater and brackish phytoplankton and cyanobacteria. J. Appl. Phycol. 15, 525–531 (2003).

Molversmyr, Å. Some effects of rotting straw on algae. SIL Proc. 1922–2010. 27, 4087–4092 (1998).

Kosiba, J., Wilk-Woźniak, E. & Krztoń, W. The effect of potentially toxic cyanobacteria on ciliates (Ciliophora). Hydrobiologia 827, 325–335 (2019).

Tapia-Larios, C. & Olivero-Verbel, J. Potentially toxic Cyanobacteria in a Eutrophic Reservoir in Northern Colombia. Water 15, 3696 (2023).

Budzyńska, A., Gołdyn, R., Zagajewski, P., Dondajewska-Pielka, R. & Kowalczewska-Madura, K. The dynamics of a Planktothrix agardhii population in a shallow dimictic lake. Oceanological Hydrobiol. Stud. 38, 7–12 (2009).

Kuczyńska-Kippen, N., Kozak, A. & Celewicz, S. Cyanobacteria respond to trophic status in shallow aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 949, 174932 (2024).

Funding

The publication was financed by the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education as part of the Strategy of the Poznan University of Life Sciences for 2024–2026 in the field of improving scientific research and development work in priority research areas. The participation of Maya Stoyneva-Gärtner was supported by the SUMMIT project No BG-RPR-2.004-0008, part 3.1.11 Algology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Ś. was responsible for methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing of the original draft, review and editing, visualization, supervision, and project administration. S.C. was responsible for methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing of the original draft, review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. M.K. was responsible for formal analysis, investigation, writing of the original draft, review and editing, and visualization. P.A. was responsible for formal analysis, writing of the original draft, visualization, and funding acquisition. K.S.-S. was responsible for methodology and formal analysis. T.S. was responsible for methodology and formal analysis. D.K.-P. was responsible for formal analysis and resources. T.K. was responsible for methodology and formal analysis. M.S.-G. was responsible for formal analysis, as well as the writing of the original draft, review and editing. S.K. was responsible for the investigation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Submission declaration

The work described has not been published previously; it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and all authors approve its publication. If accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English, or any other language, including electronically, without the copyright holder’s written consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Funding section, where the project number was incomplete. Full information regarding the correction made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Świerk, D., Celewicz, S., Krzyżaniak, M. et al. The influence of active metabolites from the decomposition of camelina and barley straw on the development of phytoplankton from eutrophic freshwater ecosystem. Sci Rep 15, 305 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82343-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82343-5