Abstract

Globally, prostate cancer is the second most common malignancy in males, with over 400 thousand men dying from the disease each year. A common treatment modality for localized prostate cancer is radiotherapy. However, up to half of high-risk patients can relapse with radiorecurrent prostate cancer, the aggressive clinical progression of which remains severely understudied. To address this, we have established an orthotopic mouse model for study that recapitulates the aggressive clinical progression of radiorecurrent prostate cancer. Radiorecurrent DU145 cells which survived conventional fraction (CF) irradiation were orthotopically injected into the prostates of athymic nude mice and monitored with bioluminescent imaging. CF tumours exhibited higher take rates and grew more rapidly than treatment-naïve parental tumours (PAR). Pathohistological analysis revealed extensive seminal vesicle invasion and necrosis in CF tumours, recapitulating the aggressive progression towards locally advanced disease exhibited by radiorecurrent tumours clinically. RNA sequencing of CF and PAR tumours identified ROBO1, CAV1, and CDH1 as candidate targets of radiorecurrent progression associated with biochemical relapse clinically. Together, this study presents a clinically relevant orthotopic model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer progression that will enable discovery of targets for therapeutic intervention to improve outcomes in prostate cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common malignancy in men worldwide, with approximately 10 million men currently living with the disease and over a million new cases being diagnosed each year1,2,3. Unfortunately, prostate cancer contributes to the deaths of over 400 thousand men annually, while causing a similar number of men to live with significant disease-related morbidity for many years3. Men living with advanced prostate cancer often experience markedly reduced quality of life, as evidenced by less vitality and poor mental health4,5. Prostate cancer therefore remains a significant contributor to cancer-related death in men globally, while also deleteriously impacting the lives of patients currently living with the disease.

External beam radiotherapy is an effective primary treatment modality for localized prostate cancer6. However, half of high-risk patients will experience biochemical relapse (BCR) within ten years of radiotherapy treatment, indicating a recurrence of their cancer in a form known as radiorecurrent prostate cancer7,8. Radiorecurrent prostate cancer is characterized by its rapid clinical progression towards incurable metastatic disease and mortality. Approximately 50% of all men with radiorecurrent prostate cancer will develop metastases within five years of biochemical relapse, with half of these men experiencing rapid onset of metastatic disease as early as one year after recurrence8.

Despite the poor outcomes of high-risk patients who relapse after radiotherapy8, the mechanisms by which radiorecurrent prostate cancer adopts an aggressive clinical phenotype continue to be understudied. Modeling radiorecurrent disease in the preclinical setting remains a challenge, in large part due to the considerable difficulty of obtaining tumour samples from a patient after relapse. To address the limited availability of radiorecurrent specimens for preclinical research, isogenic radioresistant cell lines are often generated in the laboratory setting for studying the development of radiorecurrent disease9. Previously, we generated an isogenic radioresistant model by treating the established DU145 prostate cancer cell line to daily 2 Gy doses of irradiation for a total of 59 fractions, thereby simulating the clinical scenario of conventional fractionation. Consistent with the aggressive, treatment-resistant phenotype of radiorecurrent prostate cancer observed clinically, our conventionally fractionated DU145 cell line (CF) is more radioresistant, tumorigenic, and invasive than their treatment-naïve, parental control cells (PAR) in vitro10.

Although the characterization of radioresistant cell lines in vitro is a significant first step in understanding the mechanisms of radiorecurrence, these models nevertheless fail to fully recapitulate the clinical progression of radiorecurrent cancer as it occurs within the context of the tumour microenvironment (TME). The progression of locally advanced prostate cancer involves complex interactions between the tumour cells and their local environment, resulting in changes to the tumour vasculature through angiogenesis, remodelling of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and dysregulation of surrounding stromal cell types. These changes to the TME –which occur in large part due to the effects of tumour cells on their local niche– work in concert to provide improved conditions for tumour cell survival, while also enhancing the invasive capacity of tumour cells11,12,13,14. To better understand the dynamic interactions between tumour cells and the prostate TME preclinically, the past several decades have borne witness to the establishment and refinement of orthotopic prostate cancer mouse models, in which tumour progression occurs in vivo within the TME of the mouse prostate15,16,17. These models have been integral to the preclinical study of tumour progression, drug testing, and therapy resistance within the prostate TME18,19; however, an orthotopic mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer –one which uses radiorecurrent tumour cells generated from a clinically relevant regimen of fractionated radiotherapy– has yet to be established.

In this study, we report for the first time the establishment of an orthotopic xenograft mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer, using radiorecurrent CF cells generated through conventional fractionation radiotherapy. Monitoring of tumour progression using bioluminescent imaging showed higher tumour take rates and more rapid growth of CF tumours, which was confirmed by pathohistological examination. RNA sequencing of extracted tumour RNA revealed widespread changes in transcriptional activity of CF tumours, and identified candidate targets of in vivo radiorecurrent prostate cancer progression for further characterization and therapeutic development.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic patient analysis

ICGC PRAD-CA patients with pathologically confirmed prostate cancers were used in this study. Fresh-frozen samples of treatment and hormone naïve tumors were sequenced and processed as described before20,21,22,23. Patients were treated with either radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy. Following radiotherapy, BCR was defined as an increase of more than 2.0 ng/mL above the nadir serum PSA abundance. Following radical prostatectomy, BCR was defined as two consecutive measurements of more than 0.2 ng/mL after surgery. CNAs were defined as previously described24 in 380 ICGC patients. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the relationship between ROBO1 or CAV1 amplification and BCR risk, using the survival R package v3.2–10. ICGC PRAD-CA CNA data is made available in a previous publication24.

The rate of BCR was compared between patient samples with a high CDH1 RNA abundance (upper 50%), to those with low RNA abundances (lower 50%) using a log-rank test. Analysis was conducted using a dataset from a previous publication25, accessed from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number GEO: GSE70769 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE70769) following counts per million (CPM) normalization and log2 transformation (edgeR v4.0.16)26,27. Visualizations and statistical analysis were conducted in the R statistical environment v4.2.0. Related plots were created using the BPG package v7.0.328.

Cell culture

The human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line DU145 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. The CF cell line was generated as previously described10. Cells were grown on tissue-culture flasks in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 4.5 g/L D-glucose and GlutaMAX (DMEM; Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin. The cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and passaged upon reaching 80% confluency.

Creation of lentiviral plasmids

The pLUEF1-IRES-GFP (plasmid Lentivirus UCOE-containing EF1α) vector was designed to include a ubiquitous chromatin opening element (UCOE) inserted upstream of the EF1α constitutively active promoter to reduce epigenetic silencing of the desired transgene. The UCOE was PCR amplified from pMH0006 plasmid (a gift from Martin Kampmann & Jonathan Weissman (Addgene plasmid # 135,448; RRID:Addgene_135448)) using the following primers AAGACCACCGCACAGCAAGCGCGGCCGCTGATCTTCAGACCTGGAGG forward and CAGGCACCAGAGCAGGCCGGGGCCGGCCAGCTTGAGACTACCCCCG reverse, then cloned into pWPI vector (a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid # 12,254; RRID:Addgene_12254) between Noti and Fsei restriction sites using the Gibson reaction (Gibson Assembly Mastermix, New England Biolabs # E2611S). Luciferase2 (Luc2) was then PCR amplified from pFU Luc2-eGFP (a gift from Professor Jennifer Prescher) using the following primers: cgagactagcctcgaggtttaaacATGGAAGATGCCAAAAAC forward, attcctgcagcccgtagtttaaacTTATTACACGGCGATCTTG reverse and Gibson cloned into pLUEF1-IRES-GFP between the Pmei restriction site (this is detailed in Immunological tolerance to luciferase and fluorescent proteins using Tol transgenic mice allows improved preclinical tumor models for immunotherapy and metastasis studies, a manuscript by Khan et al. under revision at the time of preparing this manuscript).

Production of lentivirus and transduction of PAR and CF cell lines

HEK293T cells (a gift from Dr David Andrew’s lab, Sunnybrook Research Institute) were used to produce lentivirus containing Luc2-IRES-GFP transgenes. HEK293T cells in 10 cm plates (3 × 106) were transfected with PEI (Sigma-Aldrich #408,727, molecular weight ~ 25,000, branched) at a ratio of 1:4 DNA:PEI. A total of 9 ug of DNA was transfected per plate including transgene, packaging and envelope vectors: pLUEF1 Luc2-IRES-GFP, psPax2 and pMD2.G, at a ratio of 3.3:2.5:1. 24 h later, transfection media was changed, and lentivirus was collected 48 h later. Lentivirus media was incubated with PAR and CF cells in the presence of 8 ug/mL of polybrene. The top 10% GFP + cells were sorted and cultured (BD, FACS Aria).

In vitro bioluminescence assay

Luciferin stock solution for in vitro use was prepared by dissolving D-luciferin sodium salt (CAT# LUCNA-100; Goldbio, USA) in molecular grade H2O (Wisent, Canada) at a concentration of 15 mg/ml. PAR and CF cells stably expressing Luc2 transgene were seeded in a 96-well plate at increasing cell concentrations: 2000, 4000, 6000, 8000, and 10 000 cells per well. Luciferin stock solution was added to the wells at a final concentration of 150 μg/ml, and allowed to incubate for at least 5 min to allow the bioluminescent reaction to occur. The plate was then placed inside the Newton FT500 imager (Vilber, France) and bioluminescent signal intensity was recorded. Mean bioluminescent signal intensity in units of ph.s-1.cm-2.sr-1 was collected from each cell-seeded well demarcated by a region of interest (ROI) using Kuant imaging analysis software (Vilber, France).

Orthotopic injection of DU145 cells

6-week old immunodeficient athymic nude mice (Crl:NU(NCr)-Foxn1nu ; strain code: 490; Charles River Lab) were anesthetized with isoflurane, and an open surgical procedure was performed as follows: a ~ 1 cm incision was made along the midline of the lower abdomen, and the bladder and seminal vesicles were externalized; the seminal vesicles were retracted to expose the dorsal lobes of the prostate; 17.5 μl of cell suspension was injected into each lobe of the prostate, for a total of 35 μl (7 × 105 cells). PAR or CF cells in DMEM (Gibco, USA) were mixed with 1mg/ml Matrigel (Corning, USA) at a 1:1 ratio to make the cell suspension for orthotopic injection. After, the peritoneum was sutured, and stainless-steel staple clips were used to close the incisions. Meloxicam was administered subcutaneously immediately post-procedure and on the following day. The stainless-steel staple clips were removed approximately 1 week later once the incisions were fully healed.

Bioluminescent imaging of mice in vivo and mouse tissue ex vivo

Luciferin stock solution for in vivo use was prepared by dissolving D-luciferin sodium salt (CAT# LUCNA-100; Goldbio, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Wisent, Canada) to a final concentration of 15 mg/ml. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 mg/kg of PBS-luciferin stock solution (200 μl total), then were allowed to move freely for 8 min to promote circulation. Mice were then anesthetized and placed in the Newton FT500 imager for bioluminescent imaging. Mean bioluminescent signal intensity in units of ph.s-1.cm-2.sr-1 was collected from a standardized region of interest (ROI) placed on the lower abdomen of each mouse using Kuant imaging analysis software. At 6 weeks post-implantation, all surviving mice were sacrificed and organs were excised. To conduct ex vivo bioluminescent imaging, excised prostates were soaked in PBS-luciferin for 1 min, imaged in the Newton FT500 imager, and bioluminescent signal intensity was quantified in units of ph.s-1.cm-2.sr-1 using Kuant imaging analysis software.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

When mice were sacrificed, excised tissue was fixed for 24 h in 10% formalin. Tissues were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histology was completed by the Histology Core Facility at Sunnybrook Research Institute. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned and immunostained with anti-GFP antibody (CAT# ab6556; Abcam, USA). Immunohistochemistry was completed by the Pathology Research Program (PRP) Laboratory at the University Health Network (UHN). Histopathological confirmation of tumour and seminal vesicle invasion in H&E slides was confirmed by a genitourinary pathologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

RNA sequencing analysis

Samples for sequencing were prepared by extracting total RNA from PAR and CF tumour tissue using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA). RNA library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis was performed by Novogene Co., LTD. (Sacramento, USA). Sample quality control and library preparation were conducted according to their outlined protocols. Sequencing was performed using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and clean reads were obtained after quality control. Reads were mapped to the reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. Gene expression was quantified with featureCounts29 v1.5.0-p3, with the FPKM of each gene calculated based on gene length and reads count mapped to the gene. Differential gene expression analysis comparing CF versus PAR tumour tissue was conducted using the DESeq2Rpackage (1.20.0)30, with differential gene expression defined as (|log2(FoldChange)|> = 1 & padj < = 0.05). Gene Ontology (GO)31 pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler R package, and GO terms were determined to be significantly enriched if the corrected P value was less than 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise stated, statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 10.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA), with all data presented as mean values with standard deviation. Significance was defined as P < 0.05. For the in vitro bioluminescence assay, a simple linear regression test was used to assess correlation of cell density and bioluminescent signal intensity. To assess differences in mean bioluminescent signal intensity of PAR and CF tumours at endpoint, the Mann–Whitney U test was used.

Ethics declarations

All animal experiments were conducted under a Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre approved animal use protocol (AUP#24,873). All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. All authors complied with ARRIVE guidelines.

Results

Workflow for establishing an orthotopic bioluminescent mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer

Before establishing our orthotopic model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer, we sought a means by which to monitor in vivo tumour growth in a minimally invasive manner. To this end, we introduced the Luc2 luciferase transgene to our radiorecurrent DU145 cells (CF) and treatment-naïve DU145 cells (PAR) via lentiviral transduction, thereby enabling their in vivo detection by bioluminescent imaging (BLI). Before implementing this BLI system to monitor tumour growth in vivo, we validated that bioluminescent signal intensity corresponded with cell density using an in vitro bioluminescence assay. Luc2-expressing PAR and CF cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at increasing densities with luciferin and imaged (Fig. 1A). Bioluminescent signal intensity was plotted, displaying a highly linear relationship with cell density in both PAR and CF cell lines (Fig. 1B). Additionally, there were no significant differences in bioluminescent signal intensity between the PAR and CF cell lines across the range of cell densities tested. These results indicate that bioluminescent signal intensities are comparable between PAR and CF cells, and can therefore be used to detect cell density as a measure of orthotopic tumour growth in vivo.

Workflow for establishing an orthotopic bioluminescent mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer. (A) Luc2-expressing PAR and CF cells are plated in a 96-well plate with luciferin at linearly increasing densities, and bioluminescent signal intensity is measured. (B) Bioluminescent signals of PAR and CF cells are quantified and fit to a simple linear regression model (PAR: r2 = 0.99, P = 0.0004; CF: r2 = 0.9813, P = 0.0011). Means, standard deviations, and statistical significance of biological replicates are shown. (C) To orthotopically implant cells into the prostates of athymic nude mice, a midline abdominal incision was made, revealing the seminal vesicles (SV) and bladder (B). (D) The seminal vesicles were gently retracted to expose the dorsal prostate lobes (P), contoured in white. (E) Cells were injected bilaterally into each lobe of the prostate via needle (parallel to yellow arrow). (F) After orthotopic injection, mice were administered 150 mg/kg of luciferin and placed in the Newton FT500 imager to monitor in vivo tumour growth with BLI.

To establish our orthotopic bioluminescent mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer, implantation of PAR and CF cells into immunodeficient athymic nude mice was conducted using an open surgical procedure. First, an incision was made along the midline of the lower abdomen, revealing the seminal vesicles and bladder of the mouse (Fig. 1C). The seminal vesicles were then gently retracted to reveal the dorsal prostate lobes (Fig. 1D). Once the prostate was exposed, cells were injected bilaterally into each lobe of the prostate to achieve orthotopic implantation (Fig. 1E). After orthotopic implantation of PAR and CF cells, mice were injected with 150 mg/kg of luciferin through intraperitoneal route and placed in the Newton FT500 imager to monitor orthotopic tumour progression by BLI (Fig. 1F). Collectively, these results illustrate a workflow for establishing an orthotopic model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer, that allows for monitoring of tumour growth in a minimally invasive manner through BLI.

Radiorecurrent orthotopic prostate tumours have accelerated growth in vivo

After successful orthotopic implantation of PAR and CF cells into athymic nude mice (n = 6 per group), BLI was conducted 24 h later to assess variations in injection efficiency between mice, then once weekly thereafter to track tumour growth until endpoint (Fig. 2A). To compare tumour progression between PAR and CF mice, the BLI signals of each individual mouse was normalized to its respective BLI signal 24 h post-injection, and plotted over time (Fig. 2B). Initially, both PAR and CF tumours grew rapidly within the first 4 weeks post-implantation, with CF tumours displaying increased growth compared to PAR tumours. Notably, however, PAR tumours entered a phase of regression at week 4, while CF tumours continued to grow steadily. CF mouse 6 succumbed to tumour-related complications before week 5, and was therefore excluded from subsequent analysis. Overall, these results demonstrate that radiorecurrent CF tumours exhibit more rapid and persistent growth than treatment-naïve PAR tumours in vivo, suggesting a greater potential for progression to locally advanced disease.

Radiorecurrent orthotopic prostate tumours have accelerated growth in vivo. (A) BLI of athymic nude mice orthotopically implanted with PAR or CF cells (n = 6 per group). BLI was conducted 24 h post-implantation, then conducted weekly until endpoint. (B) Quantified BLI signals of PAR and CF mice over time (individual tumour BLI signals were normalized to their respective BLI signals 24 h post-implantation). Means and standard deviations of biological replicates at each timepoint are shown.

Radiorecurrent prostate tumours have higher implantation rates, grow more aggressively and model locally advanced disease

At endpoint (week 6), all mice were sacrificed and prostates with intact seminal vesicles were excised. Prostates were imaged ex vivo (Fig. 3A), and BLI quantification of ex vivo tumours, normalized to their respective BLI signal 24 h post-injection, was conducted to assess tumour growth at endpoint. Although not statistically significant, CF tumours displayed greater mean BLI signal intensity compared to PAR tumours at endpoint (Fig. 3B). Bioluminescent imaging revealed the formation of large tumours concurrent with increased BLI signal in PAR mice 2 and 4, and CF mice 1, 4, 5, and 6. There were no detectable tumours in the prostates of PAR mice 1 and 3, either visually or by ex vivo BLI. A small BLI focus was detected on the prostate of PAR mouse 5; however, a larger and more intense BLI signal was detected in the excised abdominal smooth muscle wall adjacent to the prostate, suggesting the formation of an extra-prostatic tumour (imaged in the panel above PAR mouse 5 prostate, Fig. 3A). Unfortunately, PAR mouse 6 succumbed to tumour-related complications before sacrifice was possible, and the prostate could not be recovered. Ex vivo BLI of CF mouse 2 and 3 prostates revealed small bioluminescent foci with relatively low and high signal intensities, respectively, requiring further confirmation of tumour formation by histology.

Radiorecurrent prostate tumours have higher implantation rates, grow more aggressively and model locally advanced disease. (A) Ex vivo BLI of excised prostate tumours with intact seminal vesicles from PAR and CF mice. The lower panel of PAR 5 shows the prostate, while the upper panel shows the extra-prostatic tumour excised from the abdominal smooth muscle wall adjacent to the prostate. Scale bar = 1 cm. (B) BLI quantification of PAR versus CF tumours ex vivo at endpoint. Means of biological replicates are shown. (C) Histology of PAR and CF mouse prostates stained with H & E. Tumour regions are contoured in yellow. “5 (SM)” denotes the extra-prostatic tumour of PAR mouse 5. Scale bar = 2 mm.

Histological examination by a genitourinary pathologist confirmed the presence of tumours in 60% of PAR specimens (mice 2, 4, 5) and 83% of CF specimens (mice 1, 3, 4, 5, 6), thereby confirming higher rates of CF tumour take (Fig. 3C). Tumours detected in PAR mouse 5 and CF mouse 3 were confirmed to be extra-prostatic, with the tumour in PAR mouse 5 growing on the abdominal smooth muscle wall adjacent to the prostate, and the tumour in CF mouse 3 developing in the periprostatic adipose tissue. Although small BLI foci were detected on the prostates of PAR mouse 5 and CF mouse 2 ex vivo (Fig. 3A), there was no histological evidence of tumour cells within these prostates. Seminal vesicle invasion, a defining feature of locally advanced disease, was identified in 67% of PAR tumours (mice 2 and 4) and 80% of CF tumours (mice 1, 4, 5, and 6). Comedonecrosis, a characteristic of aggressive Gleason pattern 5 disease, was also present in all 4 intraprostatic CF tumours (mice 1, 4, 5, 6) and both intraprostatic PAR tumours (mice 2 and 4). To summarize, these results show that radiorecurrent CF tumours have higher rates of implantation and more rapid progression overall than treatment-naïve PAR tumours, supported by histological evidence of more locally advanced disease. These findings therefore led us to investigate the expression profile of CF tumour cells, in order to explore the cellular mechanisms driving their aggressive phenotype within the prostate TME.

Sequencing of tumour RNA reveals candidate targets of in vivo radiorecurrent progression

To investigate changes in gene expression driving local progression of radiorecurrent cancer within the prostate TME, we sequenced RNA extracted from PAR or CF tumours and compared their expression. Differential gene expression of CF versus PAR tumours was expressed as |log2(FoldChange)|> = 1 and padj < = 0.05 (Supplementary table 1). Radiorecurrent CF tumours exhibited widespread transcriptional changes in comparison to treatment-naïve PAR tumours, with 103 genes and numerous cellular pathways found to be significantly dysregulated after false discovery rate (FDR) correction (Supplementary Fig. 1). In particular, pathways involved in angiogenesis, ECM organization and remodeling, and cell migration and locomotion were among the most upregulated GO pathways in CF tumours (Fig. 4A).

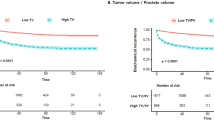

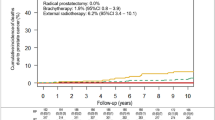

Sequencing of tumour RNA reveals candidate targets of in vivo radiorecurrent progression. (A) Gene Ontology (GO) pathways significantly enriched in orthotopic CF prostate tumours. Gene ratio on the x-axis is the ratio of the number of differential genes linked with the GO term to the total number of differential genes. The size of a point represents the number (count) of genes upregulated in the specified GO term, and colour represents significance of enrichment after p-value adjustment. (B) Workflow for selecting candidate targets of radiorecurrent progression. Integration of in vivo RNA analysis, and in vitro RNA and proteomic analysis is leveraged to find gene targets consistently dysregulated in CF cells compared to PAR control cells. (C) Expression heat map of significantly dysregulated candidate gene targets in CF tumour cells in vivo (ROBO1: log2FC = 2.03, Padj = 0.008; CAV1: log2FC = 2.01, Padj = 0.003; CDH1: log2FC = -1.57, Padj = 0.048). Kaplan–Meier plots of biochemical relapse (BCR)-free survival rate for patients in the ICGC PRAD-CA dataset with ROBO1 (D) or CAV1 (E) amplification copy number alteration (n = 380). (F) Kaplan–Meier plot of biochemical relapse (BCR)-free survival rate for patients in the GSE70769 dataset with high (upper 50%) or low (lower 50%) CDH1 RNA expression (n = 92).

To identify candidate targets of radiorecurrent progression, we selected significantly dysregulated genes involved in these pathways, and validated their expression patterns with RNA32 and proteomic33 sequencing datasets previously generated from PAR and CF cells grown in vitro (Fig. 4B). Specifically, the significance and direction of dysregulation of these gene candidates was validated against a dataset of dysregulated genes from in vitro RNA sequencing of CF versus PAR cells32 (log fold change threshold parameter was 0.5 and FDR ≤ 0.05 was set to identify significant changes), and a dataset of dysregulated genes from in vitro proteomic analysis of CF versus PAR cells33 (CF versus PAR cells with fold change > 1 and p-value < 0.05), from past investigations. If a gene target was also significantly dysregulated in the same direction in either the RNA dataset, the proteomic dataset, or both, it was considered a promising candidate target of radiorecurrent progression. ROBO1, CAV1, and CDH1 met these criteria, and therefore were investigated further for clinical outcomes (Fig. 4C). Roundabout Guidance Receptor 1 (ROBO1) was consistently upregulated at the RNA level in CF cells both in vivo and in vitro, although it was not detected in the proteomic analysis. Given the involvement of ROBO1 in angiogenesis and cellular chemotaxis GO pathways (both of which were enriched in CF tumours), we investigated clinical outcomes in prostate cancer patients from the ICGC PRAD-CA dataset, revealing that genomic amplification of ROBO1 was significantly associated with biochemical relapse (BCR; Fig. 4D). Caveolin 1 (CAV1), involved in angiogenesis-related GO pathways, was significantly upregulated in CF RNA in vivo, and CF RNA and protein in vitro; consistent with these findings, its genomic amplification in ICGC PRAD-CA patients was closely approaching statistically significant association with BCR (Fig. 4E). Finally, cadherin 1 (CDH1), the downregulation of which is well-known to promote the pro-invasive epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of cancer cells34,35, was significantly downregulated in CF tumour RNA in vivo, as well as in RNA and protein in vitro. Although genomic deletion of CDH1 was not associated with any clinical outcomes in ICGC PRAD-CA patients (Supplementary Fig. 2), reduced CDH1 RNA expression was significantly associated with BCR in prostate cancer patients from the GSE70769 dataset (Fig. 4F). Overall, these results suggest that CAV1, ROBO1, and CDH1 are among many genes involved in mechanisms essential to tumour progression such as angiogenesis, cell motility and invasion, which are upregulated in radiorecurrent tumours and associated with poor clinical outcomes.

Discussion

The rapid clinical progression of radiorecurrent prostate cancer accounts for a significant proportion of cancer related morbidity and mortality in men worldwide1,8, yet innovation of novel therapeutic approaches to address this treatment-resistant disease is severely stifled by a lack of preclinical research. Although reports of irradiation promoting tumour progression and metastatic propensity have prompted concern in the field of radiation oncology for the past several decades36,37,38,39, the molecular mechanisms conferring the aggressive radiorecurrent phenotype observed clinically remain to be fully elucidated. To address this paucity in preclinical research on radiorecurrence, our group had generated a radioresistant –and highly aggressive– prostate cancer cell line by treating DU145 cells with a conventional fractionation (CF) radiation schedule10, as delivered in the clinic. Generation and characterization of the CF cell line was previously conducted in vitro; therefore, in this work we sought to establish a methodology for orthotopic implantation of CF cells into immune-incompetent mice as a clinically relevant model for studying radiorecurrent progression in the prostate TME. To our knowledge, this is the first orthotopic mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer that uses cells treated with a clinically derived regimen of fractionated radiotherapy.

While numerous orthotopic mouse models of prostate cancer have been developed in pursuit of more clinically applicable research discoveries15,16,17,18,19, in vivo monitoring of prostate tumour progression over time poses a significant challenge due to the physical inaccessibility of the prostate. To address this issue, a variety of imaging modalities have been adapted to visualize tumour growth in mice, such as positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and ultrasound, among others40,41. For our orthotopic prostate model described herein, we used bioluminescence as an imaging modality to monitor in vivo tumour progression as it is minimally invasive, and uses a methodology that is accessible to most researchers in the field of oncology who come from different training backgrounds. Moreover, the simultaneous detection of BLI signal in all organs harbouring tumour cells from a single whole-body image provides a rapid and efficient means of tracking tumour cell dissemination in mice, making this model well-suited for future metastatic studies.

Consistent with the aggressive clinical progression of radiorecurrent prostate cancer8, radiorecurrent CF tumours in our orthotopic model had higher rates of tumour take and grew more rapidly than treatment-naïve PAR tumours. Furthermore, these results also validate our previous in vitro studies10, in which CF cells exhibited increased cellular proliferation and soft agar colony formation compared to PAR cells. Soft agar assays are commonly used as an in vitro assessment of anchorage-independent growth that is considered to be strongly associated with tumorigenicity in vivo42; our in vivo observations thus corroborate the results of our in vitro proliferation and tumorigenicity assays. Additionally, pathohistological examination by a genitourinary pathologist confirmed high rates of seminal vesicle invasion –corroborating the increased invasive capacity of CF cells observed in vitro10– and extensive comedonecrosis in CF tumours. The presence of comedonecrosis in prostate tumours is a hallmark of Gleason pattern 5, the most aggressive histopathological classification of prostate cancer, and is an independent prognostic factor for BCR and metastasis-free survival43. Therefore, our orthotopic model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer is characteristic of high-grade, locally advanced disease, recapitulating the aggressive clinical phenotype of radiorecurrence. Although CF mouse 2 was the only CF-implanted mouse not to show histological evidence of tumour formation, ex vivo BLI of the prostate revealed a small BLI focus, similar to the minor BLI focus found on the histologically tumour-negative prostate of PAR mouse 5. Given that an extra-prostatic tumour was discovered on the abdominal smooth muscle wall adjacent to the PAR mouse 5 prostate, it is reasonable to infer that the ex vivo BLI signal of the CF mouse 2 prostate was likely indicative of an extra-prostatic growth that was lost during excision or subsequent sectioning for histological analysis. These findings thus highlight the utility in using ex vivo BLI in future studies to localize visually subtle tumour foci, to enable more selective histological analysis of regions of interest within a given tissue.

Tumour cells engage in an interactive relationship with their local niche, whereby tumour-induced microenvironmental remodeling evokes the release of signaling cues that in turn can alter the gene expression of tumour cells. These changes in expression alter their cellular phenotype, often resulting in further microenvironmental remodeling, while also promoting their growth, survival, and invasion –features that are necessary for prostate cancer to progress to locally advanced disease12,13,14. To investigate how radiorecurrence changes the transcriptomic profile of prostate cancer specifically in the TME, we sequenced RNA extracted from our PAR and CF tumours. Global transcriptomic changes were observed in CF tumours when compared to their PAR counterparts, including significant upregulation in pathways known to drive local progression, such as those related to ECM remodeling and cell motility. The most significantly enriched GO pathway, however, was angiogenesis, a compelling process to explore in vivo as it is a prominent mechanism by which tumour cells remodel their local milieu to support survival. Angiogenesis promotes the progression of highly proliferative tumours that commonly outgrow their own vasculature, initiating the formation of new blood vessels in response to hypoxic conditions. However, constitutive angiogenic signaling in tumour cells –occurring due to prolonged hypoxic exposure– stimulates the formation of immature, abnormally formed blood vessels44. The poorly organized and highly permeable vasculature that is formed in consequence facilitates tumour cell intravasation to promote metastasis, while also further contributing to the formation of hypoxic niches that promote therapy resistance and pro-invasive phenotypes in tumour cells45,46.

Given the significance of angiogenesis as a critical hallmark of tumour progression in vivo47,48, we identified significantly upregulated genes in the GO angiogenesis pathway of CF tumours, and cross-validated their expression patterns with our RNA and proteomic datasets comparing CF and PAR cell expression in vitro; as a result, we selected ROBO1 and CAV1 as consistently upregulated candidate targets of radiorecurrent progression. Roundabout guidance receptor 1 (ROBO1) is part of the immunoglobulin family of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), and is involved in axon migration guidance and tissue development, in addition to angiogenesis49,50. Although there are conflicting reports regarding the role of ROBO1 in cancer51,52,53, its activity in osteosarcoma, colorectal and prostate cancers has been associated with increased tumour progression and metastatic potential51,54,55,56. Furthermore, inhibition of its angiogenic signaling in vascular endothelial cells has been shown to reduce microvessel densities and tumour growth in vivo57. Caveolin 1 (CAV1) is a scaffolding protein and key structural component required for the formation of caveolae at the plasma membrane of cells, thereby playing an important role in endocytosis58. While CAV1 can also act as both a tumour suppressor and promoter depending on cancer type and stage59, its previous association with poor clinical prognosis in prostate cancer and its involvement in tumorigenesis, tumour progression, and invasion have been well established60,61. Notably, it has been shown that expression and secretion of CAV1 by prostate cancer cells functions to promote angiogenesis within the prostate TME by eliciting endothelial cell migration and tubule formation, thereby driving tumour progression and metastasis62. Upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors such as ROBO1 and CAV1 might account for the sustained growth of our orthotopic CF tumours beyond week 4 post-implantation, at which point the PAR tumours began a phase of regression. Whereas the treatment-naïve PAR tumours may begin to outgrow their vasculature after 4 weeks of rapid growth, the radiorecurrent CF tumours might sustain their aggressive progression through increased angiogenic neovascularization. Finally, in addition to ROBO1 and CAV1, we also explored clinical associations with CDH1 in prostate cancer. Cadherin 1 (CDH1), or epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin), was significantly downregulated at the RNA level in our CF tumours, as well as at the RNA and protein levels in CF cells in vitro. CDH1 is a junctional protein essential to the cell–cell adhesion of epithelial cells, and loss of its expression is a critical step in the process of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), in which cancer cells adopt a more invasive, mesenchymal cellular phenotype34,35,63,64. Irradiation of cancer cells has previously been reported to promote EMT-induced cell motility65; therefore, reduction of CDH1 expression in our CF tumour cells may be one mechanism by which radiorecurrence enhances cell motility to promote locally advanced disease.

Future studies comparing our in vitro and in vivo CF RNA datasets will be conducted to identify expression changes that occur as a direct result of the TME. Indeed, previous comparative expression analyses between in vitro and in vivo cancer culture has highlighted the significant changes in expression that occur due to growth in an orthotopic environment, and the oncogenic consequences this imparts on the phenotype of the cancer cell66. By comparing the pathway analyses of CF vs PAR tumours (in vivo; Fig. 4A) and CF vs PAR cells (in vitro)32, we observed that angiogenesis, cell motility, and ECM organization are enriched in vivo, whereas MYC targets, G2M checkpoints, E2F targets, and EMT are enriched in vitro. This implies that there are distinct molecular changes resulting from the tumour microenvironment that are not captured in the in vitro model.

There are several limitations to this study that warrant addressing in future research. Firstly, the immune component of the TME is missing from our immune-deficient xenograft mouse model. To this end, our group is currently investigating the role of the immune compartment within the prostate TME using a syngeneic mouse model. Secondly, although BLI is an ideal modality to track progression of distant metastases, the aggressive growth of our tumours resulted in termination of our experiments before the formation of distant metastases, due to complications from urinary retention caused by malignant obstruction of the urethra. Orthotopic models of metastatic progression are more clinically representative than other in vivo metastatic models such as tail vein injection, since tumour cells must successfully overcome all stages of the metastatic cascade, including invasion and intravasation at the primary site. Future work using a small animal irradiator, for example, could provide a clinically relevant means of controlling primary tumour growth to allow sufficient time for tumour cells to metastasize. During in vivo BLI of our mice, weak bioluminescent foci did in fact appear in distant organs such as the testes, liver, spleen, and lungs; however, IHC staining confirmed there were no GFP-luciferase-expressing tumour cells in these tissues (Supplementary Fig. 3). This indicates that non-specific BLI signals can occur away from the primary tumour site, which could confound studies of metastatic spread. Future metastatic experiments will need to be optimized to account for this, such as setting a BLI signal threshold for detecting tumours forming at secondary sites. Furthermore, although the mean BLI signal intensity of CF tumours was greater than PAR tumours ex vivo at endpoint, this difference was not statistically significant, likely due to the small sample size. Additional studies using a greater number of mice in each group will improve the statistical power, to allow for a fully quantitative assessment of tumour growth using BLI. It would also be beneficial to conduct histological analysis of tumours at earlier timepoints –before total replacement of the prostate by tumour cells– since this may reveal microenvironmental changes known to promote tumour progression and invasion, such as ECM remodeling. Pathways involved in ECM remodeling were significantly enriched in our RNA sequencing analysis of CF tumours, and previous work by our group has revealed that CF cells upregulate collagen remodelling proteins such as PLOD2, which was shown to promote their invasive and metastatic potential67. Finally, the DU145 cell line is castrate-resistant, and thus cannot fully model the earlier stage of hormone-sensitive radiorecurrent prostate cancer. Future studies should focus on generating radiorecurrent models from either established hormone-sensitive prostate cancer lines, or primary patient-derived prostate cancer cells.

In conclusion, we have established an orthotopic, bioluminescent mouse model of radiorecurrent prostate cancer that exhibits aggressive progression towards locally advanced disease, recapitulating the clinical reality of radiorecurrence. Using this model, we have identified candidate targets of radiorecurrent progression such as ROBO1, CAV1, and CDH1, all of which are shown to be prognostic for biochemical relapse in prostate cancer patients. Overall, this study provides a clinically relevant model for elucidating potential therapeutic targets for future development, to ultimately suppress the aggressive clinical progression of radiorecurrent prostate cancer and improve outcomes in our high-risk patients.

Data availability

The significant differentially expressed genes from our RNA sequencing analysis are uploaded as a separate Microsoft Excel file in the supplementary information files (Supplementary table 1). RNA sequencing data has been deposited to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under PRJNA1168545. Otherwise, all data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article.

References

Wong, M. C. et al. Global incidence and mortality for prostate cancer: Analysis of temporal patterns and trends in 36 countries. Eur. Urol. 70, 862–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.043 (2016).

Collaborators, G. D. a. I. I. a. P. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 (2018).

Sandhu, S. et al. Prostate cancer. Lancet 398, 1075–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00950-8 (2021).

Albertsen, P. C., Aaronson, N. K., Muller, M. J., Keller, S. D. & Ware, J. E. Health-related quality of life among patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 49, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00485-2 (1997) (discussion 216-207).

Eton, D. T. & Lepore, S. J. Prostate cancer and health-related quality of life: A review of the literature. Psychooncology 11, 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.572 (2002).

Rebello, R. J. et al. Prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0 (2021).

Zumsteg, Z. S. et al. The natural history and predictors of outcome following biochemical relapse in the dose escalation era for prostate cancer patients undergoing definitive external beam radiotherapy. Eur. Urol. 67, 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.028 (2015).

Philipson, R. G. et al. Patterns of clinical progression in radiorecurrent high-risk prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 80, 142–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2021.04.035 (2021).

McDermott, N., Meunier, A., Lynch, T. H., Hollywood, D. & Marignol, L. Isogenic radiation resistant cell lines: Development and validation strategies. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 90, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.3109/09553002.2014.873557 (2014).

Fotouhi Ghiam, A. et al. Long non-coding RNA urothelial carcinoma associated 1 (UCA1) mediates radiation response in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 8, 4668–4689. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.13576 (2017).

Barker, H. E., Paget, J. T., Khan, A. A. & Harrington, K. J. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3958 (2015).

Winkler, J., Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A., Metcalf, K. J. & Werb, Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 11, 5120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18794-x (2020).

Bonnans, C., Chou, J. & Werb, Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 786–801. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3904 (2014).

Cox, T. R. The matrix in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-00329-7 (2021).

Stephenson, R. A. et al. Metastatic model for human prostate cancer using orthotopic implantation in nude mice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 84, 951–957. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/84.12.951 (1992).

Shahryari, V. et al. Pre-clinical orthotopic murine model of human prostate cancer. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/54125 (2016).

Chaudary, N. et al. An orthotopic prostate cancer model for new treatment development using syngeneic or patient-derived tumors. Prostate 84, 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.24701 (2024).

Park, S. I. et al. Targeting SRC family kinases inhibits growth and lymph node metastases of prostate cancer in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Cancer Res. 68, 3323–3333. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2997 (2008).

Tumati, V. et al. Development of a locally advanced orthotopic prostate tumor model in rats for assessment of combined modality therapy. Int. J. Oncol. 42, 1613–1619. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1858 (2013).

Espiritu, S. M. G. et al. The evolutionary landscape of localized prostate cancers drives clinical aggression. Cell 173, 1003-1013.e1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.029 (2018).

Sinha, A. et al. The proteogenomic landscape of curable prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 35, 414-427.e416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.005 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell. 176, 831-843.e822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.025 (2019).

Bhandari, V. et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor hypoxia across cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51, 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0318-2 (2019).

Lalonde, E. et al. Tumour genomic and microenvironmental heterogeneity for integrated prediction of 5-year biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 15, 1521–1532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71021-6 (2014).

Ross-Adams, H. et al. Integration of copy number and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: A discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2, 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.017 (2015).

Robinson, M. D. & Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 11, R25. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25 (2010).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26, 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 (2010).

Png, C. et al. BPG: Seamless, automated and interactive visualization of scientific data. BMC Bioinformatics. 20, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-2610-2 (2019).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 30, 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 (2014).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 (2010).

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14 (2010).

Haas, R. et al. The proteogenomics of prostate cancer radioresistance. Cancer Res. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-24-0292 (2024).

Kurganovs, N. et al. A proteomic investigation of isogenic radiation resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 15, e2100037. https://doi.org/10.1002/prca.202100037 (2021).

Yang, J. & Weinberg, R. A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev. Cell 14, 818–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.009 (2008).

Polyak, K. & Weinberg, R. A. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2620 (2009).

Strong, M. S. et al. A randomized trial of preoperative radiotherapy in cancer of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Am. J. Surg. 136, 494–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(78)90268-4 (1978).

Kaplan, H. S. & Murphy, E. D. The effect of local roentgen irradiation on the biological behavior of a transplantable mouse carcinoma; increased frequency of pulmonary metastasis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 9, 407–413 (1949).

von Essen, C. F. Radiation enhancement of metastasis: a review. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 9, 77–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01756381 (1991).

Vilalta, M., Rafat, M. & Graves, E. E. Effects of radiation on metastasis and tumor cell migration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 2999–3007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2210-5 (2016).

Lyons, S. K. Advances in imaging mouse tumour models in vivo. J. Pathol. 205, 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1697 (2005).

Puaux, A. L. et al. A comparison of imaging techniques to monitor tumor growth and cancer progression in living animals. Int. J. Mol. Imaging. 2011, 321538. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/321538 (2011).

Shin, S. I., Freedman, V. H., Risser, R. & Pollack, R. Tumorigenicity of virus-transformed cells in nude mice is correlated specifically with anchorage independent growth in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 72, 4435–4439. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.72.11.4435 (1975).

Hansum, T. et al. Comedonecrosis gleason pattern 5 is associated with worse clinical outcome in operated prostate cancer patients. Mod. Pathol.. 34, 2064–2070. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00860-4 (2021).

Lugano, R., Ramachandran, M. & Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 77, 1745–1770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03351-7 (2020).

Gilkes, D. M., Semenza, G. L. & Wirtz, D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 14, 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3726 (2014).

Semenza, G. L. Cancer-stromal cell interactions mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors promote angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, and metastasis. Oncogene 32, 4057–4063. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.578 (2013).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 (2011).

Welch, D. R. & Hurst, D. R. Defining the hallmarks of metastasis. Cancer Res. 79, 3011–3027. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0458 (2019).

Ypsilanti, A. R., Zagar, Y. & Chédotal, A. Moving away from the midline: New developments for slit and robo. Development 137, 1939–1952. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.044511 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Slit2 promotes angiogenic activity via the robo1-VEGFR2-ERK1/2 pathway in both in vivo and in vitro studies. Invest. Ophthalmol Vis. Sci. 56, 5210–5217. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs-14-16184 (2015).

Zhao, S. J. et al. SLIT2/ROBO1 axis contributes to the Warburg effect in osteosarcoma through activation of SRC/ERK/c-MYC/PFKFB2 pathway. Cell. Death Dis. 9, 390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0419-y (2018).

Parray, A. et al. ROBO1, a tumor suppressor and critical molecular barrier for localized tumor cells to acquire invasive phenotype: study in African-American and caucasian prostate cancer models. Int. J. Cancer 135, 2493–2506. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28919 (2014).

Feng, Y., Feng, L., Yu, D., Zou, J. & Huang, Z. srGAP1 mediates the migration inhibition effect of Slit2-Robo1 in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 35, 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-016-0469-x (2016).

Zhang, Q. Q. et al. Slit2/Robo1 signaling promotes intestinal tumorigenesis through Src-mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Oncotarget 6, 3123–3135. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3060 (2015).

Yao, Y. et al. Activation of slit2/robo1 signaling promotes tumor metastasis in colorectal carcinoma through activation of the TGF-β/smads pathway. Cells. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8060635 (2019).

Kim, S. H. et al. ROBO1 protein expression is independently associated with biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer patients who underwent radical prostatectomy in Asian patients. Gland Surg. 10, 2956–2965. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-21-406 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by slit-robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking robo activity. Cancer Cell 4, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8 (2003).

Parton, R. G. Caveolae: structure, function, and relationship to disease. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 34, 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617-062737 (2018).

Gupta, R., Toufaily, C. & Annabi, B. Caveolin and cavin family members: dual roles in cancer. Biochimie. 107(Pt B), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2014.09.010 (2014).

Bian, Q. et al. Molecular pathogenesis, mechanism and therapy of Cav1 in prostate cancer. Discov. Oncol. 14, 196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-023-00813-0 (2023).

Thompson, T. C. et al. The role of caveolin-1 in prostate cancer: clinical implications. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 13, 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2009.29 (2010).

Tahir, S. A. et al. Tumor cell-secreted caveolin-1 has proangiogenic activities in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2668 (2008).

Dongre, A. & Weinberg, R. A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4 (2019).

Nauseef, J. T. & Henry, M. D. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer: paradigm or puzzle?. Nat. Rev. Urol. 8, 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2011.85 (2011).

Jung, J. W. et al. Ionising radiation induces changes associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation and increased cell motility of A549 lung epithelial cells. Eur. J. Cancer 43, 1214–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.034 (2007).

Hum, N. R. et al. Comparative molecular analysis of cancer behavior cultured in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030690 (2020).

Frame, G. et al. Targeting PLOD2 suppresses invasion and metastatic potential in radiorecurrent prostate cancer. BJC Rep. 2, 60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-024-00085-3 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Petia Stefanova and the Histology Core Facility at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre for their histology services. The authors would also like to thank the Pathology Research Program (PRP) laboratory at the University Health Network (UHN) for their immunohistochemistry services. Finally, the authors would like to thank Ping Xu for facilitating usage of the Newton FT500 imager.

Funding

S.K.L acknowledges the very kind support provided by Wayne and Maureen Squibb. G.F. is supported by the Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s (CGS-M) from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, The Strategic Training in Transdisciplinary Radiation Science for the 21st Century Program (STARS21) co-funded by Princess Margaret Research (PMR) and the Radiation Medicine Program (RMP) at UHN, and by the Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology (QEII-GSST) funded by the Terry Fox Programme, Sunnybrook, the Province of Ontario and the University of Toronto. S.K.L received research funding from Prostate Cancer Canada Movember Discovery Grant (D2017- 1811). S.K.L and T.K. received funding from Project Grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (PJT-162384) (PJT-189979). S.K.L and T.K. also received funding from the Canadian Cancer Society Challenge Grant (grant #708133), the Prostate Cancer Canada Movember Rising Star (RS2014-03), and the Prostate Cancer Fight Foundation/Ride for Dad. R.H. is supported by EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship ALTF (1131–2021) and the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (22YOUN32). P.C.B. is supported by Prostate Cancer Foundation (20CHAS0), Early Detection Research Network (1U2CCA271894-01 and 3U01CA214194-0552) and NIH Informatics Technology for Cancer Research (ITCR) (1U24CA248265-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.F., X.H., R.H., K.A.K, H.S.L., T.K., P.C.B., M.D., S.K.L. contributed to study design. G.F., X.H., R.H., K.A.K performed the experiments. G.F., X.H., K.A.K, R.H. performed data analysis and figure preparation. G.F. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. H.S.L., T.K., P.C.B., M.D., S.K.L. supervised the research. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.C.B. sits on the scientific advisory board of Intersect Diagnostics Inc., BioSymetrics Inc., Sage Bionetworks. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frame, G., Huang, X., Haas, R. et al. Accelerated growth and local progression of radiorecurrent prostate cancer in an orthotopic bioluminescent mouse model. Sci Rep 14, 31205 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82546-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82546-w