Abstract

The unique saddle articulation of the trapeziometacarpal joint allows for a wide range of motion necessary for routine function of the thumb. Inherently unstable characteristics of the joint can lead painful instability. In this study, we modified a surgical dorsal ligament reconstruction technique for restoring trapeziometacarpal joint stability. We evaluated and compared the biomechanical efficacy of our reconstruction technique with that of dorsoradial capsulodesis by creating a cadaveric model of rotational instability. Twenty-four specimens were subjected to dorsoradial capsulodesis (n = 12) or dorsoradial ligament reconstruction using the abductor pollicis longus (APL) (n = 12). The modified dorsoradial ligament reconstruction entailed detaching one distally based slip of the APL. The harvested tendon’s proximal end was passed through a bone tunnel created at the dorsoradial ridge of the trapezium. A suture anchor was inserted at the dorsal base of the metacarpal bone. The tendon stump was sutured to the metacarpal bone using fiber wire in figure-of-eight configuration. The load to failure of the trapeziometacarpal joint under compression was higher in the reconstruction group (p = 0.003). The improvement in the rotational arc (observed in all specimens) was significantly greater in the reconstruction group than the capsulodesis group (p = 0.003). Our technique reconstructs only the necessary ligament, requires a smaller incision and relatively simpler surgical procedure, and enables precise determination of the insertion and exit sites of the tendon, making it a promising treatment for trapeziometacarpal joint instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The trapeziometacarpal (TM) joint is a complex anatomical structure composed of the trapezium and metacarpal bone of the thumb. It is supported by surrounding ligaments that maintain its unstable double-saddle articulation1. The morphology of the TM joint enables various thumb movements such as pinching, gripping, and opposition. Instability of the TM joint leads to alterations in joint kinematics, resulting in increased contact stress2, pain, and cartilage damage3. In addition, TM joint instability contributes to the development of osteoarthritis4,5,6. To prevent progression of arthritis, ligament reconstruction has been attempted in the initial stages of TM joint arthritis (stage 1 in the Eaton-Glickel classification7) and in the event of failure of conservative treatment8.

Instability of the TM joint can be caused by various factors, including repeated overuse, trauma, and congenital disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan syndromes, which can weaken the ligaments supporting the joint9,10. Previously, the volar beak ligament was thought to be the primary stabilizer of the TM joint2,4,5,11,12; however, recent biomechanical cadaveric studies have shown that the dorsoradial ligament is the primary stabilizer that prevents dorsal dislocation of the thumb metacarpal base13,14,15,16. Furthermore, during pinching or grasping, the volar beak ligaments are relaxed and the dorsoradial ligaments are tensed, whereas in the resting position, the dorsoradial ligaments are relaxed17. These findings highlight the significance of the dorsoradial ligament as a key stabilizer of the TM joint.

In 1973, Eaton and Littler proposed a reconstruction procedure using half of the flexor carpi radialis tendon that mimicked the anatomy of the volar beak ligaments4. Since then, various surgical methods have been proposed. As the importance of the dorsoradial ligament as a stabilizer emerged, Rayan and Do devised capsulodesis by imbricating the dorsoradial ligament18, and Birman et al. devised dorsoradial ligament imbrication using a suture anchor10. Zeba et al. introduced a dorsal ligament reconstruction technique using the abductor pollicis longus (APL) tendon with a tenodesis anchor; however, the clinical efficacy of this technique has not been evaluated19. We devised a modification of the surgical technique introduced by Zeba et al. to simplify dorsoradial ligament reconstruction. In our modified procedure, we detached one distally based slip of the APL, passed it through a bone tunnel in the trapezium and anchored it to the dorsum of the metacarpal base using a suture.

In the study, we aimed to evaluate the biomechanical efficacy of our reconstruction technique using a cadaveric model and compare it with that of dorsoradial capsulodesis.

Results

The characteristics of the cadavers used in this study are summarized in Table 1. The median age of the cadavers was 72 (IQR 68.5–80.3) years. The specimens included eight male and four female cadavers. The causes of death included cancer, sepsis, septic shock, heart failure, and pneumonia.

One pair of specimens was excluded from the study because of fracture of the metacarpal bone during bone tunneling for ligament reconstruction. Therefore, 22 specimens (11 per group) were included in the experiments. During the rotation test, the rotational arc values increased after cutting the dorsoradial ligament and decreased after the procedure for each specimen (Fig. 4).

The biomechanical outcomes are presented in Table 2. Prior to the procedure, no significant differences were observed in the initial arc of motion or the arc after ligament transection between the two groups (p = 0.238 and 0.095, respectively). However, after the procedure, the arc of motion differed significantly between the groups (p = 0.003). Furthermore, changes in the values of the arcs before and after the procedure were statistically significant (p = 0.003), as were the ratios of the post-procedure to pre-procedure angles, indicating a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.003). The compression test showed that median value of the load to failure was 296.3 N (241.8 to 376.7) in the capsulodesis group and 528.4 N (403.4 to 663.9) in the reconstruction group. In addition, there were significant differences between the groups in the compression tests (p = 0.003).

Discussion

In our cadaveric study, cutting the dorsoradial ligament led to increased rotational instability in all specimens. However, after the procedures, each specimen showed improvement in the rotation arc in both groups. Notably, the reconstruction group showed greater improvement than the capsulodesis group, and the load to failure was higher in the reconstruction group during the compression test.

The results of our study suggest that the dorsoradial ligament plays a significant role in stabilizing the TM joint because its transection resulted in increased instability. We countered TM joint instability using our modified dorsoradial ligament reconstruction technique with a distally based slip of the APL tendon. Our technique has several advantages over reconstruction using the flexor carpi radialis tendon4. First, our modified method reconstructs only the necessary ligament, resulting in a smaller incision and relatively simpler surgical procedure. Moreover, unlike previous dorsoradial ligament reconstruction techniques19,20, the APL tendon is passed through a bone tunnel created in the trapezium and fixed with a suture anchor in a figure-of-eight manner. This technique facilitates precise determination of the insertion and exit sites of the tendon, and the contact area between the tendon and bone for healing21 is wider than that of other dorsoradial ligament reconstruction techniques.

Previous studies have evaluated the role of the dorsoradial ligament in TM joint stability13,14,15, and our findings are consistent with their results. The arc of rotation after dorsoradial ligament transection and the difference in the angles before and after the procedure were similar to those reported in previous studies. Moreover, capsulodesis was effective in addressing TM joint instability, as demonstrated by the decreased angles after the procedure. However, the arc of motion in the rotational test was significantly greater in the capsulodesis group than in the reconstruction group. Moreover, the load-to-failure force was higher in the reconstruction group. We performed reconstruction using the tendon and passed it through a bone tunnel. In contrast, the joint capsule was duplicated and sutured in the capsulodesis group. Generally, tendons have higher tensile strength and stiffness than joint capsules22,23,24,25,26. The higher tensile strength and stiffness of tendons are due to the abundance of collagen fibers, which are organized in a highly aligned and parallel manner to resist tensile forces. In contrast, joint capsules have a more disorganized and loosely packed collagen structure that is better suited for resisting compressive and shear forces27. These material properties may have contributed to our results.

The results of the compression test showed that the median value of the load to failure was 296.3 N (241.8–376.7) in the capsulodesis group and 528.4 N (403.4 to 663.9) in the reconstruction group. In a previous study, the load to failure for an uninjured TM joint was reported as 217.76 N (SD = 66.03)28. When comparing this to the load to failure values observed following our procedures, both surgical techniques in this study demonstrated values exceeding those of the uninjured joint. This indicates that both techniques provide satisfactory resistance to axial flexion load on the joint. Notably, the reconstruction group exhibited higher load to failure than the capsulodesis group. These load test results align with the trends observed in rotational test comparisons between normal joints and post-surgical outcomes, suggesting that the reconstruction technique may offer greater stability to the joint. The maximal average values of key pinch power are 76.4–102.9 N29, indicating that a higher force is typically applied at the TM joint in pinch positions.

Our study had several limitations. First, the procedures were performed on cadavers. Cadaveric specimens do not have the same physiological functions as living humans and therefore, may not accurately represent the in vivo conditions of the surgical procedure. Therefore, the healing process occurring within the bone tunnel or fibrosis during each procedure cannot be reflected in cadaveric specimens. Second, the cadavers were older than the age at which TM joint instability is typically encountered. However, paired tests were performed on each cadaver to minimize errors and increase the reliability of the results. Third, no standardized method was used to evaluate the applied force in the rotational test. To minimize errors, one experimenter conducted the experiment and fixed the camera during the experiment for each specimen. Fourth, the sample size was relatively small, as we used 11 cadavers and 22 specimens. Therefore, the generalizability of our results is limited.

In conclusion, our cadaveric study suggests that dorsoradial ligament reconstruction using a distally based slip of the APL tendon may be a promising option for the treatment of TM joint instability. The procedure resulted in improved stability in the rotational and compression tests compared with dorsoradial capsulodesis. However, further studies, particularly clinical trials, are required to verify our findings and assess the long-term outcomes of the procedure.

Methods

Rotational test

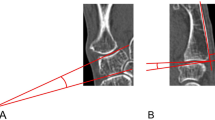

Twelve fresh frozen cadavers were used in this study. The specimen was fixed by inserting a 2.8-mm Steinmann pin into the radius (Fig. 1A). A camera was placed at a fixed position during the experiment for each specimen. The first metacarpal bone, trapezium, and their joints were exposed by dissecting the skin and subcutaneous tissue and cutting the extensor pollicis longus and brevis. A 1.6-mm Kirschner wire was drilled into the radial styloid and metacarpal shaft, distal to the joint capsule. One author (S. H. Kim) rotated the distal Kirschner wire to the point of maximal laxity to prevent interobserver variability. Photographs were captured at the point of maximal laxity during supination and pronation (Fig. 1B and C). The angles between the two Kirschner wires were measured using the Infinitt PACS program. The dorsoradial ligament was removed to induce joint instability (Fig. 2A) and the same experiment was repeated.

Rotational test of capsulodesis group and reconstruction group. To induce TM joint instability, we cut the dorsal ligament in the cadaver study. (A) The specimen was fixed by inserting a 2.8 mm Steinmann pin into the radius. And the skin and subcutaneous tissue were incised, the extensor pollicis longus and brevis were cut, and the first metacarpal bone, trapezium, and their joints were exposed, and a 1.6 mm Kirschner wire was inserted into the radial styloid and metacarpal shaft, which are distal to the joint capsule. (B, C) The Kirschner wire inserted in the distal part was rotated to the supination and the pronation until the maximum laxity point.

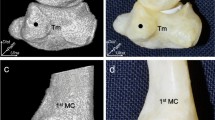

Capsulodesis group and reconstruction group model making procedure. A series of steps illustrate the experimental procedures and comparisons between the capsulodesis and reconstruction groups: (A) The dorsoradial ligament was cut from a normal joint to induce instability prior to each procedure. (B) Dorsoradial ligament reconstruction was performed using the abductor pollicis longus (APL) tendon. (C) Dorsoradial capsulodesis was performed. (D) graphic schematic showing the dorsoradial ligament reconstruction technique. One distally based slip of the APL tendon was detached, passed through a bone tunnel in the trapezium, and anchored to the dorsum of the metacarpal base using a suture. (E) A graphic schematic illustrating the dorsoradial capsulodesis technique.

Twelve cadavers (24 specimens) were divided into two groups and subjected to dorsoradial capsulodesis (group A, n = 12) or dorsoradial ligament reconstruction using the APL tendon (group B, n = 12). Paired (contralateral) specimens were assigned to each of the two groups to minimize differences, with an equal ratio of left to right sides in both groups.

In group A, dorsoradial capsulodesis was performed using a previously described technique30. In brief, the TM joint was anatomically reduced by abducting and pronating the thumb metacarpal shaft, followed by overlapping and imbrication of the ligaments and capsules. Finally, the joint was repaired with six 3 − 0 Ethibond sutures under maximum tension to ensure strong and durable repair (Fig. 2B). In group B, dorsoradial ligament reconstruction was performed as follows. First, a half-slip of the APL tendon was harvested by cutting it at 4 cm proximal to the TM joint. Thereafter, bone tunnels were created at the dorsoradial ridge of the trapezium from the dorsal to the radial side using a 2.5 mm drill bit. The proximal end of the harvested tendon was passed through the trapezial bone tunnel in the dorsal to radial direction. A 3 − 0 suture anchor was inserted at the dorsal base of the metacarpal bone. Finally, the tendon stump was sutured to the metacarpal bone using fiber wire in figure-of-eight configuration (Fig. 2C and D). After the procedure, the same author performed a rotational test similar to that performed before the procedure.

Biomechanical test

To test the load to failure (under compression) of the TM joint, each specimen was separated from the cadaver and the base of the trapezium was positioned on a jig. The specimen was then fixed using unsaturated resin (EC-304, Aekyung Chemical Co.) and a load was applied to the metacarpal head, flexing the TM joint until the dorsal structure failed (Fig. 3). Throughout the experiment, all data on the applied loads were saved on a computer. All mechanical loading tests were performed using an Instron 3366 electrodynamic testing machine (Instron Co. Ltd., Norwood, MA, USA) (Fig. 4).

The load to failure (under compression) of TM joint using electrodynamic testing machine. To compare the results of the compression test between the capsulodesis group and the reconstruction group, the TM joint was separated from the cadaver and the base of the trapezium was positioned on a jig. The TM joint was flexing until the dorsal structure failed when a load was applied to the metacarpal head.

Data and statistical analyses

Using the rotational data, we analyzed the angles in each condition (before the procedure, dorsoradial ligament, and capsule transection, and after the procedure) and plotted a graph to depict the change in the angle or ratio in each specimen. For the compression data, we generated elasticity and load graphs to depict the force pattern until joint failure. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to determine the normality of distribution of each variable. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as means and standard deviation. Medians and interquartile ranges were reported for variables showing non-normal distribution. A paired t-test was used to compare the two procedures. A pilot study was conducted using three cadavers. Three specimens each were assigned to the capsulodesis and reconstruction groups. The mean difference in the ratio after the procedure between the two groups was 0.17 and the standard deviation was 0.03. Power analysis indicated that a sample size of 8 was required to achieve 80% power at an alpha level of 0.05.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

06 December 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Affiliation 1 was incomplete. The correct affiliation is listed here. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, International St. Mary's Hospital, Catholic Kwandong University College of Medicine, Incheon, South Korea. Additionally, this Article omitted an affiliation for Sang-Hee Kim. His correct Affiliations are 1 and 2. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Bettinger, P. C. et al. An anatomic study of the stabilizing ligaments of the trapezium and trapeziometacarpal joint. J. Hand. Surg. 24(4), 786–798 (1999).

Pellegrini, V. D. Jr, Olcott, C. W. & Hollenberg, G. Contact patterns in the trapeziometacarpal joint: the role of the palmar beak ligament. J. Hand. Surg. 18(2), 238–244 (1993).

Rust, P. A. & Tham, S. K. Ligament reconstruction of the trapezial-metacarpal joint for early arthritis: a preliminary report. J. Hand. Surg. 36(11), 1748–1752 (2011).

Eaton, R. G. & Littler, J. W. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. JBJS 55(8), 1655–1666 (1973).

Pellegrini, V. D. Jr Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: the pathophysiology of articular cartilage degeneration. I. anatomy and pathology of the aging joint. J. Hand. Surg. 16(6), 967–974 (1991).

CHO, K. O. Translocation of the abductor pollicis longus tendon: a treatment for chronic subluxation of the thumb carpometacarpal joint. JBJS 52(6), 1166–1170 (1970).

Eaton, R. G. & Glickel, S. Z. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 3(4), 455–469 (1987).

Athlani, L. Trapeziometacarpal joint ligament reconstruction in early stages of first carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. Hand Surg. Rehabilitation. 40, S42–S45 (2021).

Takwale, V., Stanley, J. & Shahane, S. Post-traumatic instability of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb: diagnosis and the results of reconstruction of the beak ligament. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. Vol. 86(4), 541–545 (2004).

Birman, M. V. et al. Dorsoradial Ligament Imbrication for Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint instability. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 18(2), 66–71 (2014).

Pieron, A. P. The mechanism of the first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint: an anatomical and mechanical analysis. Acta Orthop. Scand. 44(sup148), 1–104 (1973).

Imaeda, T. et al. Anatomy of trapeziometacarpal ligaments. J. Hand. Surg. 18(2), 226–231 (1993).

Strauch, R. J., Behrman, M. J. & Rosenwasser, M. P. Acute dislocation of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb: an anatomic and cadaver study. J. Hand. Surg. 19(1), 93–98 (1994).

Van Brenk, B. et al. A biomechanical assessment of ligaments preventing dorsoradial subluxation of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J. Hand. Surg. 23(4), 607–611 (1998).

Lin, J. D., Karl, J. W. & Strauch, R. J. Trapeziometacarpal joint stability: the evolving importance of the dorsal ligaments. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Research®. 472, 1138–1145 (2014).

D’Agostino, P. et al. Comparison of the anatomical dimensions and mechanical properties of the dorsoradial and anterior oblique ligaments of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J. Hand. Surg. 39(6), 1098–1107 (2014).

Edmunds, J. O. Current concepts of the anatomy of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. J. Hand. Surg. 36(1), 170–182 (2011).

Rayan, G. & Do, V. Dorsoradial capsulodesis for trapeziometacarpal joint instability. J. Hand. Surg. 38(2), 382–387 (2013).

Zeba, N., Horvath, A. & Wallmon, A. First carpometacarpal joint instability: dorsal ligament reconstruction. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 25(3), 169–174 (2021).

Stauffer, A. et al. Outcomes after thumb carpometacarpal joint stabilization with an abductor pollicis longus tendon strip for the treatment of chronic instability. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 140, 275–282 (2020).

Rodeo, S. A. et al. Tendon-healing in a bone tunnel. A biomechanical and histological study in the dog. JBJS 75(12), 1795–1803 (1993).

Benedict, J. V., Walker, L. B. & Harris, E. H. Stress-strain characteristics and tensile strength of unembalmed human tendon. J. Biomech. 1(1), 53–63 (1968).

Wren, T. A. et al. Mechanical properties of the human achilles tendon. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 16(3), 245–251 (2001).

Hansen, P. et al. Mechanical properties of the human patellar tendon, in vivo. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 21(1), 54–58 (2006).

Little, J. S. & Khalsa, P. S. Material properties of the human lumbar facet joint capsule. J. Biomech. Eng. 127(1), 15–24 (2005).

Rachmat, H. et al. Material properties of the human posterior knee capsule. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 25(2), 177–187 (2015).

Neumann, D. A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal system-e-book: Foundations for Rehabilitation(Elsevier Health Sciences, 2016).

Preston, H. et al. Anatomic and biomechanical study of Thumb Carpometacarpal dislocations: a Laboratory Study. HAND 19(4), 637–642 (2024).

Jansen, C. W. S. et al. Measurement of maximum voluntary pinch strength:: effects of forearm position and outcome score. J. Hand Ther. 16(4), 326–336 (2003).

Chenoweth, B. A. et al. Efficacy of dorsoradial capsulodesis for trapeziometacarpal joint instability: a cadaver study. J. Hand. Surg. 42(1), e25–e31 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-H.K. and Y.-R.C. conceptualized the study and developed the methodology. Software usage was managed by S.-H.K., H.-K.K., D.-H.K., and J.-Y.C. The investigation was conducted by S.-H.K., W.-T.O., and I.-H.K., while Y.-R.C. provided the necessary resources. Visualization was handled by S.-H.K., H.-K.K., D.-H.K., and J.-Y.C. Project administration was managed by S.-H.K. and Y.-R.C., with supervision provided by Y.-R.C. The original draft was written by S.-H.K. and Y.-R.C., and reviewed and edited by S.-H.K. and Y.-R.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statements

The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System (approval number: 4-2024-0659). Informed consent was obtained for the use of cadavers legally donated to the Surgical Anatomy Education Centre at Yonsei University College of Medicine. The authors confirm that all applicable local and international ethical guidelines and laws for the use of human cadaveric donors in anatomical research were followed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SH., Kim, HK., Kim, DH. et al. Dorsoradial ligament reconstruction versus imbrication for restoring trapeziometacarpal joint stability: a comparative biomechanical study. Sci Rep 14, 31372 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82714-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82714-y