Abstract

Elevated Body Mass Index in infertile women has important implications for medically assisted reproduction. The prevalence and impact of elevated BMI on assisted reproductive technology treatment outcomes in low-income settings remain under-studied and little known. This study investigated the prevalence of elevated BMI and associated socio-demographic characteristics among infertile women in Ghana. Retrospective analysis of five-years data of 3,660 infertile women attending clinic in Ghana for assisted conception treatment was carried out. The data was analysed using the SPSS-22; descriptive statistics performed and chi square used to assess associations between categorical variables, p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Overall, 76.83% of women with infertility had elevated BMI, of whom 39.56% were obese and 37.27% were overweight. Majority of participants with elevated BMI was aged between 30–49 years. (p < 0.001). Infertility prevalence and BMI increased with increasing level of education (p < 0.003). Secondary infertility was more common among overweight or obese women. Traders had the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity followed by civil servants and health workers. Elevated BMI was highly prevalent among women seeking infertility care in Ghana, particularly so among those with secondary infertility. Traders had the highest prevalence of elevated BMI, probably reflecting their predominantly sedentary lifestyles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity has become a major global public health challenge over the past few decades because of its established health risks and its rising prevalence worldwide1,2. Previously considered a problem of only high-income countries, overweight and obesity from recent studies in low and middle income countries, have been shown to be attaining global epidemic proportions affecting nearly all countries2. According to the World Obesity Atlas 2023 Report, 38% of the global population are currently either overweight or obese, with an alarming projection that over half of the global adult population would be affected by 20353.

Elevated BMI levels co-existing with various degrees of underweight have been demonstrated in several African countries including Nigeria and other Sub-Saharan African countries, giving rise to the double-burden of malnutrition4,5. In the case of Ghana, a similar trend of increasing levels of overweight and obesity has been reported in recent years6 – 9 The health risks of overweight and obesity have been established and include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemias, increased risk of stroke and heart attacks, increased risk of malignancies (breast, endometrial and colon), and an overall escalated risk of early death10. Additionally, overweight and obesity are associated with poor reproductive health outcomes including infertility, delayed time-to-conception, increased risk of miscarriage and increased risk of macrosomia leading to increased risk of caesarean section. Among women with infertility, the elevated BMI, adversely impacts their health and infertility treatment outcomes including Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs). Obese and overweight women often require higher doses of gonadotropins for longer durations11,12,13 due to poorer response to ovarian stimulation14. Women with elevated BMI produce poorer quality oocytes and embryos14,15,16,17, due to higher prevalence of oocyte morphological abnormalities18,19 resulting in significantly lower numbers of embryos available for transfer. Further, they have lower pregnancy rates with increased rates of miscarriages compared to non-obese controls15,20.

Studies on the prevalence of elevated BMI among infertile women attending ART facilities is limited globally. Our literature search revealed very scanty data available on this subject globally, with one such study among 60 purposively selected Indian infertile women21. Despite its importance, prevalence of abnormal BMI among women seeking infertility treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has not received the needed research attention. This study sought to document this and fill the knowledge gap on the subject in the Ghanaian context while providing evidence to inform preventive interventions.

Method

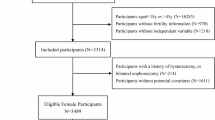

This retrospective study involved the review and analysis of a five-year archived data of patients from 2012 to 2017 who attended the Ruma Fertility and Specialist Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana, to seek treatment for infertility. The data was retrieved from patients’ case notes in the hospital’s main database and included data of all females 18years and above. The study protocol was approved, and permission granted by the management of Ruma Hospital (RUMA/PT/OL/019/030) before data collection commenced. Ethical clearance and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for the study were granted by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. (CHRPE/AP/135/20). The research methodology, data collection, analysis, and reporting processes have been carried out with full compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All necessary approvals and informed consent have been obtained, and the rights and confidentiality of all participants have been safeguarded.

Patients who visited the hospital with complaints other than infertility were excluded from the study, as well as those with missing BMI records.

Data obtained focussed on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics; patients’ body mass index (BMI) in kilogram per square meter; type and duration of infertility in years. The sociodemographic characteristics included patients’ age, occupation, educational level, religion, and marital status. Infertility was categorized as ‘primary’ if the woman had never been pregnant, and ‘secondary’ if she had ever been pregnant irrespective of its outcome. The patients’ BMI were categorised as: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2); normal weight (18.5 kg/m2 – 24.99 kg/m2); overweight (25.0 kg/m2 – 29.99 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). The weight, height and the BMI were calculated with an electronic scale (JENIX® height, weight, and BMI measuring system – model: DS-103-South Korea). The electronic scale simultaneously measured the three afore-mentioned indices automatically and displayed results digitally. The resulting data was entered in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, cleaned and exported into SPSS (version 22; Chicago, IL) for analysis. Data was summarized as frequencies and proportions. Chi-square test was used to test for associations between demographic characteristics and BMI measurement categories. All reported p-values were considered statistically significant at a level of p-value below 0.05.

Results

A total of 3,660 patients reported for infertility treatment over the study period and were included in the review. The ages of the patients ranged between 18 and 68 years, the mean age was 36years, with standard deviation 7 years (36 + 7). Majority of the participants 51.94% (1,898/3,660) seeking infertility treatment was in the 30–39 years age category, whilst 2.20% (80/3,660) of the women were aged 50years and above. (Table 1).

Approximately half, 47.24% (1,729/3,660) of the respondents had completed secondary education; 45.90% (1,680/3660) completed tertiary education; 5.82% (213/3660) completed primary education; and 1.04% (38/3660) had no formal education. Christianity was the dominant religion practised by 90.98.% (3,330/3660) of the participants and Islam by 9.02% (330/3,660) (Table 1).

Majority of participants, 91.83% (3,361/3660) were married, 4.64% (170/3660) were in relationships, 3.22% (118/3660) were single, while 0.08% (3/3,660) and 0.22% (8/3,660) were divorced or widowed respectively.

Overall, the average weight and height of the participants were 75 kg ± 14.8 and 1.6 m ± 0.1 respectively. Regarding participants’ BMI, 39.56% (1,446/3,660) and 37.27% (1,363/3,660) of participants were obese and overweight respectively; whilst 22.35% (818/3,660) and 0.82% (30/3,660) had normal weight and underweight respectively (Table 1).

Of participants who were overweight, 51.47% (702/1,364) were aged between 30–39years, 25.15% (343/1,364) were within 40–49years, whilst 21.48% (293/1,364) were 18–29 years (Table 2).

Of the obese participants, 53.52% (775/1,448) were between 30 and 39 years, 31.08% (450/1,448) were between 40–49years, whilst 12.50% (181/1,448) were between ages 18–29years, and 2.90% (42/1,448) were at least 50 years old (Table 2).

Comparing the educational levels of participants and their BMI categories, it was found that, overweight participants, 47.87% (653/1,364) had secondary education whilst 45.60% (622/1,364) had tertiary education. Only 5.57% (76/1,364) of the overweight participants had primary education with 0.95% (13/1,364) having had no formal education.

Of the participants who were obese, the majority, 50.62% (733/1,448) had attained secondary education and 42.54% (616/1,448) had tertiary education. Only 5.87% (85/1,448) of these participants had primary education whilst 0.96% (14/1,448) had no formal education (Table 3).

As indicated in Tables 4 and 63.05% (860/1,364) of the patients diagnosed with secondary infertility were overweight with the remaining being primary infertility patients. A similar trend was observed in those with obesity with 63.19% (915/1,448) of the patients who were obese had secondary infertility.

Analysis of the type of infertility in relation to the BMI category revealed that, majority of the women with both primary 36.95% (504/1,364) and secondary infertility 63.05% (860/1,364) were overweight. Similarly, most of the participants who were obese had primary 36.81% (533/1448) and secondary 63.19% (915/1,448). This analysis illustrates an increase prevalence of both primary and secondary amongst the overweight and obese BMI categories (Table 4).

Significantly higher number of clients who were overweight (457) and obese (526) had infertility duration of 2–5 years compared with those who were of normal weight (295). Similarly, higher number of clients who were overweight (464) and obese (498) had infertility duration of 6–10 years compared with those who were of normal weight. This showed that in all BMI categories, the duration of infertility was longer in overweight and obese clients than in clients with normal weight (Fig. 1).

Further, the highest occurrence of overweight and obesity was amongst traders (508 and 533 respectively) followed by civil servants (328 and 345 respectively). The least occurrence of overweight and obesity was amongst students and health workers (Fig. 2).

As indicated in Table 5, only two parameters - age and level of education of participants had statistically significant associations with their BMI categories (p < 0.05). The remaining characteristics showed no association with BMI scale.

Discussion

This study reviewed the body mass index distribution of women seeking infertility treatment in Ghana.

From this study, the mean age and BMI of women seeking infertility treatment were 35.50years and 29.08 kg/m2 respectively. This is comparable to findings reported from a similar study by Owiredu WKBA, et al., on the association of anthropometric indices with hormonal imbalance among women with infertility who sought treatment at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana8.

Overall, 76.83% of the women with infertility at the Ruma Fertility and Specialist Hospital were obese (39.56%) and overweight (37.27%), with just over one-fifth (22.35%) having normal BMI. The prevalence of overweight and obesity from our study appears much higher than findings from a previous similar study by Shanthakumari K, et al.21 that reported 35% of infertile women to be overweight and obese in India. The proportions of normal and underweight were comparable from these two studies21. Again, the prevalence of overweight and obesity from our study appears higher than those reported from a systematic review on the epidemic of obesity in Ghana in the same year of our study7 and among participants of the earlier Women’s Health Study of Accra, Ghana9.

This high prevalence found from our study is over twice what Asosega et al. reported as an overall prevalence of overweight/obesity among reproductive-age women in Ghana as 35.4%, without a breakdown of those who were fertile or infertile, nor the various BMI categories of participants50. Further, the Ghana Demography and Health Survey (2022) reported a lower 50% prevalenc of overweight or obesity among Ghanaian women51.

Admittedly, while our current study was among a clinical cohort of women with infertility, the other studies were among women in the general population and not necessarily those with infertility. As a result, and seeing the availability of evidence that suggest a link between elevated BMI and infertility, our study population may have demonstrated such a high prevalence due the inherent selection bias of our population of women with infertility22. Our findings are also consistent with the research evidence that indicates the prevalence of infertility in obese women is on the ascendancy15, and that increasingly larger numbers of women seeking medical intervention to achieve pregnancy are reportedly overweight or obese23,24.

Similarly, infertility has been reported to be three-fold higher in obese women than non-obese women, with reduced overall pregnancy probability when the woman’s BMI exceeds 29 kg/m215,25.

Our study found that a significant majority of women with elevated BMI were between 30 to 49years, in keeping with existing evidence that BMI generally increases with age among urban women28,29 with women within the 35 and 44 year age-bracket reportedly having the highest odds of being overweight and obese, according Agbeko et al.30. The rural – urban distribution of elevated BMI was not included in this retrospective review.

Our current study also found that infertility and BMI increase with participants’ educational level. These findings are consistent with previous studies which revealed that higher education was associated with twice the tendency of becoming overweight or obese in women, compared with women with lower education30,39. It also agrees with evidence that women with tertiary education had the highest prevalence of obesity compared with less literate and illiterate women29. However, this finding appears to contrast other researchers’ reports that indicated a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among women with no or low education compared with those with secondary education or higher in seven Sub-Saharan African countries4. The disparity may probably be explained by the fact that our review focused on a clinical cohort of women with infertility, and differs from the continent-wide non-clinical based health survey among those seven African countries.

Another important finding in this current study is that many more obese and overweight women presented with secondary than primary infertility, suggesting the possibility that elevated BMI plays a major role in secondary infertility. A plausible explanation could be the effect of retained pregnancy-related weight gain from their previous pregnancies, however, this may not entirely account of early loss of previous pregnancies. This is consistent with research finding which suggest that childbearing is a risk factor for BMI elevation40, and that for every childbirth there is a risk of 7% increase in BMI41, as women usually struggle to lose all the weight gained during pregnancy30,42.

In terms of occupation, the risk of being obese and overweight was greatest among traders, followed closely by civil servants, artisans, health workers and students. This finding reflects the national narrative by Ofori-Asenso et al., that, in Ghana, women tend to settle for more sedentary occupations such as table-top trading, resulting in lower levels of physical activity among Ghanaian women than men36. Further, the elevated BMI risk among health workers agrees with findings of high level of physical inactivity and compromised dietary habits such as late night eating as contributory factors to overweight and obesity among Nurses and Midwives in Ghana46. Occupation dictates an individual’s physical or sedentary activity level, and together with behavioural lifestyle and socioeconomic characteristics, may potentially influence the propensity for elevated BMI43,44,45.

Overall, only two among the seven main sociodemographic characteristics, namely age and level of education had significant associations with elevated BMI. This finding is in line with findings from a previous Health Survey data by Agbeko et al.30 and a large Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) involving 32 Sub-Saharan African countries by Neupane et al.47 who observed a positive significant association between age, education, wealth, and overweight and obesity. However, findings from a similar prevalence study done among clinical cohorts in Mangalore, India by Shanthakumari21 found no such associations. This may possibly be explained by their limited sample size of only 60 infertile women.

Strengths and limitations of study

To the best of our information, this work has been the first such research to analyse elevated BMI and associated sociodemographic parameters among women with infertility in Ghana. Additionally, data collection was done by highly trained research assistants comprising Nurses and Health Information Technologists in this reputable fertility hospital with very stringent internal data quality assurance mechanisms in place.

The results of this research must be interpreted with cautions because of the limitation of retrospective archival research methodology. Notably among these limitations, our findings cannot assign causality of infertility as only due to elevated BMI from our work. Also, the inherent disadvantages of the tendency of selection bias need to be considered.

Finally, generalizability of the present study is limited because it was based on data from a single ART service provider in Ghana.

There is therefore the need for an expanded prospective follow-up study involving a representative sample of women attending multiple fertility hospitals in Ghana to give a wider and more representative picture of the prevalence of elevated BMI among this clinical cohort.

Conclusion

Overall, 76.83% of the women with infertility at Ruma, in Ghana had elevated BMI, made up of 39.56% obese and 37.27% overweight, while 22.35% have normal BMI. The participants’ age and level of education were significantly associated with elevated BMI. Elevated BMI was more prevalent among women with secondary infertility.

Increased awareness creation on the prevalence, impact and prevention of elevated BMI among women needs to be prioritized in Ghana.

Recommendations for further research

On the basis of our findings, we recommend a more rigorous prospective, multi-center research design to further examine the impact of elevated BMI on fertility and pregnancy outcomes in our Ghanaian context to inform public health policy and interventions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Amiri, P. et al. Which obesity phenotypes predict poor health-related quality of life in adult men and women? Tehran Lipid and glucose study. PLoS ONE 13(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203028 (2018).

Ng, M. et al. Global, regional and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults 1980–2013: A systematic analysis. Lancet 384(9945), 766–781 (2014).

Koliaki, C., Dalamaga, M. & Liatis, S. Update on the obesity epidemic: after the sudden rise, is the upward trajectory beginning to flatten?. Curr. Obes. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-023-00527-y (2023).

Ziraba, A. K., Fotso, J. C. & Ochako, R. Overweight and obesity in urban Africa: A problem of the rich or the poor?. BMC Public Health 9, 1–9 (2009).

Chukwuonye, I. I. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adult Nigerians - A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 6, 43–47 (2013).

Lartey, S. T. et al. Rapidly increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in older Ghanaian adults from 2007–2015: Evidence from Who-sage waves 1 & 2. PLoS One 14(8), 1–16 (2019).

Ofori-Asenso, R., Agyeman, A. A., Laar, A. & Boateng, D. Overweight and obesity epidemic in Ghana - A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3901-4 (2016).

Owiredu, W. K. B. A. et al. Weight management merits attention in women with infertility: A cross-sectional study on the association of anthropometric indices with hormonal imbalance in a Ghanaian population. BMC Res Notes 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4593-5 (2019).

Duda, R. et al. Prevalence of obesity in women of Accra, Ghana. Afr. J. Health Sci. 14(3), 154–159 (2008).

Must, A. et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 282(16), 1523–1529 (1999).

Rittenberg, V. et al. Effect of Body Mass Index on IVF Treatment Outcome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Vol. 23, 421–439 (Elsevier, 2011).

Bellver, J. et al. Female obesity impairs in vitro fertilization outcome without affecting embryo quality. Fertil. Steril. 93(2), 447–454 (2010).

Metwally, M. et al. Effect of increased body mass index on oocyte and embryo quality in IVF patients. Reprod. Biomed. Online 15(5), 532–538 (2007).

Khairy, M. & Rajkhowa, M. Effect of obesity on assisted reproductive treatment outcomes and its management: A literature review. Obstet. Gynaecol. 19(1), 47–54 (2017).

Dağ, Z. Ö. & Dilbaz, B. Impact of obesity on infertility in women. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 16(2), 111–117 (2015).

Pandey, S., Pandey, S., Maheshwari, A. & Bhattacharya, S. The impact of female obesity on the outcome of fertility treatment. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 3(2), 62–67 (2010).

Vural, F., Vural, B. & Çakiroglu, Y. The role of overweight and obesity in in vitro fertilization outcomes of poor ovarian responders. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 5–9 (2015).

Depalo, R. et al. Oocyte morphological abnormalities in overweight women undergoing in vitro fertilization cycles. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 27(11), 880–884. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2011.569600 (2011).

MacHtinger, R. et al. The association between severe obesity and characteristics of failed fertilized oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 27(11), 3198–3207 (2012).

Bellver, J. et al. Obesity and poor reproductive outcome: The potential role of the endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 88(2), 446–451 (2007).

Shanthakumari, K., Frank, R. W. & Tamrakar, A. Prevalence of obesity among infertile women visiting selected infertility clinic at mangalore with a view to develop an informational pamphlet. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 3(3), 07–10 (2014).

Wilkes, S. & Murdoch, A. Obesity and female fertility: A primary care perspective. J. Fam. Plan Reprod. Health Care 35(3), 181–185 (2009).

Garalejic, E. et al. A preliminary evaluation of influence of body mass index on in vitro fertilization outcome in non-obese endometriosis patients. BMC Womens Health 17(1), 1–9 (2017).

Vahratian, A. & Smith, Y. R. Should access to fertility-related services be conditional on body mass index?. Hum. Reprod. 24(7), 1532–1537 (2009).

Rich-Edwards, J. W. et al. Adolescent body mass index and infertility caused by ovulatory disorder. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 171(1), 171–177 (1994).

Chaurasiya, D., Gupta, A., Chauhan, S., Patel, R. & Chaurasia, V. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of obesity among reproductive-age women in India. SSM Popul. Health 9(June), 100507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100507 (2019).

Gouda, J. & Prusty, R. K. Overweight and obesity among women by economic stratum in Urban India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 32(1), 79–88 (2014).

Wilk, P., Maltby, A. & Cooke, M. Changing BMI scores among Canadian Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, youth and young adults: Untangling age, period, and cohort effects. Can. Stud. Popul. 44(1–2), 28–41 (2017).

Amoah, A. G. Sociodemographic variations in obesity among Ghanaian adults. Public Health Nutr. 6(8), 751–757 (2003).

Agbeko, M. P., Akwasi, K. K., Andrews, D. A. & Gifty, O. B. Predictors of overweight and obesity among women in Ghana. Open Obes. J. 5(1), 72–81 (2013).

Abdulai, A. Socio-economic characteristics and obesity in underdeveloped economies: Does income really matter?. Appl. Econ. 42(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701604313 (2010).

Allman-Farinelli, M. A., Chey, T., Bauman, A. E., Gill, T. & James, W. P. T. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian adults from 1990 to 2000. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 62(7), 898–907 (2008).

An, R. & Xiang, X. Age–period–cohort analyses of obesity prevalence in US adults. Public Health 141, 163–169 (2016).

Agrawal, P., Gupta, K., Mishra, V. & Agrawal, S. Effects of sedentary lifestyle and dietary habits on body mass index change among adult women in India: Findings from a follow-up study. Ecol Food Nutr. 52(5), 387–406 (2013).

Galobardes, B. & Morabia, A. B. M. The differential effect of education and occupation on body mass and overweight in a sample of working people of the general population. Ann. Epidemiol. 10(8), 532–537 (2000).

Mirowsky, J. & Ross, C. E. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Res Aging 20(4), 415–449 (1998).

Thompson, B. et al. Baseline fruit and vegetable intake among adults in seven 5 A day study centers located in diverse geographic areas. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 99(10), 1241–1248 (1999).

Caban-Martinez, A. J. et al. Leisure-time physical activity levels of the US workforce. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 44(5), 432–436 (2007).

Yaya, S. & Ghose, B. Trend in overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Uganda: 1995–2016. Obes. Sci. Pract. 5(4), 312–323 (2019).

Wolfe, W. S. Parity-associated body weight: Modification by sociodemographic and behavioral factors. Obes. Res. 5(2), 131–141 (1997).

Martorell, R., Kettel Khan, L., Hughes, M. L. & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. Obesity in women from developing countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 54(3), 247–252 (2000).

Abubakari, A. R. et al. Prevalence and time trends in obesity among adult West African populations: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 9(4), 297–311 (2008).

Allman-Farinelli, M. A., Chey, T., Merom, D. & Bauman, A. E. Occupational risk of overweight and obesity: An analysis of the Australian health survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 5(1), 1–9 (2010).

Barlin, H. & Mercan, M. A. Occupation and obesity: Effect of working hours on obesity by occupation groups. Appl. Econ. Finance https://doi.org/10.11114/aef.v3i2.1351 (2016).

Kajitani, S. Which is worse for your long-term health, a white-collar or a blue-collar job?. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 38, 228–243 (2015).

Duodu, C. Assessment of overweight and obesity prevalence among practicing nurses and midwives in the hohoe municipality of the volta region, Ghana. Sci. J. Public Health 3(6), 842 (2015).

Neupane, S., Prakash, K. C. & Doku, D. T. Overweight and obesity among women: Analysis of demographic and health survey data from 32 Sub-Saharan African Countries. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2698-5 (2016).

Bolboacă, S. D., Jäntschi, L., Sestraş, A. F., Sestraş, R. E. & Pamfil, D. C. Pearson-fisher chi-square statistic revisited. Information 2(3), 528–545 (2011).

Van Der Steeg, J. W. et al. Obesity affects spontaneous pregnancy chances in subfertile, ovulatory women. Hum. Reprod. 23(2), 324–328 (2008).

Asosega, K. A., Adebanji, A. O. & Abdul, I. W. Spatial analysis of the prevalence of obesity and overweight among women in Ghana. BMJ Open 11, e041659. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041659 (2021).

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and ICF. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2022: Summary Report (GSS and ICF, 2023).

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the Management and Staff of the Ruma Specialist Hospital and Fertility Center for their immense support to make this study very successful.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A. and R.K.A. co-designed the study and data extraction form. C.A. and E.K.A. participated in proposal writing, data collection and analysis. R.K.A. supervised proposal writing and data collection. C.A., E.K.A. and P.E.S. drafted the first version of the manuscript and P.E.S. is responsible for correspondence. All authors participated in manuscript writing and review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for the study were granted by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. (CHRPE/AP/135/20). The study was conducted in accordance with the fundamental ethical principles outlined in the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Policy, which encompasses the Declaration of Helsinki (1996), International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP E6) Guidelines, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) principles, the Belmont Report, and applicable laws and statutory regulations of Ghana and the University. By adhering to these esteemed guidelines, we ensured the highest ethical standards in the design, implementation, and reporting of our research.

Consent to participate

The research methodology, data collection, analysis, and reporting processes have been carried out with full compliance to the above ethical standards. All necessary Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals were obtained from the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. (CHRPE/AP/135/20); informed consent obtained, and the rights and confidentiality of all participants have been safeguarded.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amoah, C., Adageba, R.K., Appiah, E.K. et al. Obesity and overweight and associated factors among women with infertility undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment in a low income setting. Sci Rep 15, 6163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82818-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82818-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

IVF and pregnancy outcomes: the triumphs, challenges, and unanswered questions

Journal of Ovarian Research (2025)

-

Health of adipose tissue: oestrogen matters

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2025)