Abstract

Passive temperature sensing systems based on the Internet of Things (IoT) present an efficient, reliable, and convenient solution for temperature monitoring with extensive application prospects and market value. This paper introduces a passive, battery-free, chipless, metasurface temperature sensing tag. The key insight is that the sensing tag uses vanadium dioxide (\(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)) to solve the problems of measuring distance, large size, and high cost related to active devices. The sensing tag fabricated with tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder demonstrated a significant variation in the reflection magnitude within the temperature range of 34–42 °C. It was achieved through coating, sintering, metasurface design, and ion beam etching. Experimental results showed that the square resistance of the prepared coating decreased from 1003 to 90 \({\Omega }/{\square }\) as the temperature increased from 34 to 42 °C. Additionally, the reflection magnitude of the tag significantly increased with the temperature decrease in the 3.5–5.27 GHz frequency band. These results indicate that the passive temperature sensing tags can achieve rapid and accurate temperature sensing within the 34–42 °C range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of the Internet of Things (IoT), sensors, and smart monitoring systems represents the forefront of advancements in sensing technology. Passive temperature sensing systems, leveraging IoT, play a critical role in monitoring the temperature of objects and environments, ensuring safety across various applications. For both humans and other warm-blooded animals, body temperature serves as a fundamental indicator of health, and a deviation in body temperature may indicate serious health problems1. Effective temperature monitoring facilitates timely diagnosis and treatment, preventing life-threatening conditions and minimizing economic losses. Given the high transmissibility of many pathogens through droplets and contact, and the constant mobility of target populations, it is imperative to research methods capable of rapid, remote, and accurate temperature detection2,3.

Current temperature monitoring methods, such as infrared thermometers, offer efficient and convenient body temperature measurements. However, these devices are susceptible to external environmental interference, leading to inaccurate readings. The limited measurement range hinders their effectiveness in detecting the temperature, especially when the target is obstructed by complex barriers. The algorithm of radiation calibration data correction has been proposed in previous research to improve measurement accuracy. However, these solutions are device-specific and impractical for large-scale deployment due to the need for individualized calibration of each instrument4.

In contrast, radio frequency (RF)-based temperature sensing can demonstrate superior accuracy with reduced external interference. Traditional active RF devices require power modules, which increase device size and necessitate frequent power supply replacements, escalating costs. Although existing passive RF devices address these issues, they rely on near-field coupling coils for energy acquisition. The rapid attenuation of near-field radiation intensity and limited transmitter power constrain their communication range, typically to tens of centimeters. Extending this range to several meters would require substantial power increment, which is not feasible for low-power devices or applications5.

Materials with high-temperature sensitivity are needed to address these challenges. When applied to passive devices, these materials should respond swiftly to RF signals under minor temperature changes. These materials can enhance the measurement distance and accuracy while minimizing environmental interferences and reducing costs. Vanadium dioxide (\(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)), a typical phase-change material, exhibits a reversible transition between its insulating phase (\(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(M)) and metallic phase (\(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(R)) at around 68 °C. This phase transition, accompanied by significant changes in the crystal structure and physicochemical properties, can be fine-tuned through doping and applying stress6,7,8,9. Consequently, \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) materials hold promise for diverse applications, including smart windows10,11, sensors12,13,14,15,16,17,18, infrared stealth technologies19,20, etc.

\(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) preparation methods include the synthesis of thin films and powders. Thin film preparation, primarily via magnetron sputtering21,22 and atomic layer deposition23, offers high-quality thin films with excellent phase-change capabilities. However, these methods are costly, require specific substrates, and involve complex processes unsuitable for large-scale production. In contrast, \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder preparation methods, such as hydrothermal synthesis24,25, pyrolysis26,27, and sol–gel28,29, a low-cost and scalable alternative. \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders can be transformed into coatings or inks to affiliate on various substrates. This will promote rapid, large-scale production and widespread commercial applications.

Meanwhile, metasurface technology has been introduced into the design of temperature sensing tags to further enhance the response amplitude of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) tags to electromagnetic waves. The \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) thin film can be designed as a periodic two-dimensional pattern structure to form a frequency selective surface (FSS) metasurface30. Utilizing the unique spatial filtering characteristics of FSS greatly improved the level of changes in the electromagnetic wave response during the phase transition of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating.

This paper proposes a passive temperature sensing tag based on tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\). Firstly, \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was prepared using the hydrothermal method, and the phase transition temperature of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) was reduced to 36–38 °C by tungsten doping. Secondly, the tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was configured into an ink and coated on a quartz glass substrate, and the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating was obtained after sintering. The corresponding FSS structure was designed using simulation software, which enabled the structure to achieve more obvious changes in the reflected signal when the temperature changed. This helped the detection and analyze of the reflected signal. Then, the prepared coatings were subjected to ion beam etching to etch the simulated FSS structures. Finally, Our sensor demonstrates high accuracy, resolution, and stability within 34–42 °C, showing a significant reflection coefficient change (2.04 dB per 1 °C) and stable polarization response. Key advantages include remote, non-contact measurement, high sensitivity due to \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) phase transition, robustness against environmental interference, cost-effectiveness for large-scale use, and selective frequency response, making it ideal for industrial and commercial remote temperature monitoring applications.

Experiments

Synthesis of tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder

We systematically optimized the phase, morphology, and crystallinity of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) through repeated experiments that adjusted precursor ratio, reaction temperature, time, and annealing conditions, confirming their impact on product purity. Firstly, a certain amount of oxalic acid in a beaker was weighed, ultrapure water was added, and it was stirred to dissolve. We waited until the oxalic acid was completely dissolved and then added a certain amount of vanadium pentoxide (\(\hbox{V}_{2}\hbox{O}_{5}\)) to the solution; the molar ratio of oxalic acid and \(\hbox{V}_{2}\hbox{O}_{5}\) was 2:1. The precursor solution was stirred at a constant temperature of 50 °C for 45 min. A certain amount of ammonium metatungstate was added as a tungsten doping source, and the stirring was continued at a constant temperature for 45 min. In the next step, the solution was filled into the reactor and put into a blast drying oven for hydrothermal reaction at a reaction temperature of 240 °C for 24 h. The reaction was carried out in a drying oven at a temperature of 240 °C for 24 h. After the reaction, the products were centrifuged with ultrapure water and anhydrous ethanol, washed, dried, and finally put into a drying oven at 60 °C for 12 h to obtain the tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(B) powder.

The dried B-phase tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was fully ground and placed in an alumina crucible for high-temperature annealing in a tube furnace. Vacuum and nitrogen were introduced before annealing. The material was annealed under a nitrogen atmosphere at 700 °C for 4 h to obtain the M-phase tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder. Figure 1 shows the synthesis process of the tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder.

Preparation of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) inks and \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coatings

Pineol and Triton X-100 were mixed in a mass ratio of 3:1, heated, and stirred homogeneously. Ethylcellulose with a mass ratio of 20% was added slowly, and heating and stirring were continued until the ethyl cellulose was completely dissolved. Then, the tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder and an organic solvent were mixed in a mass ratio of 1:1. Finally, the inks were fully dispersed by an ultrasonic crusher. The prepared quartz glass substrate was washed with acetone, anhydrous ethanol, and ultrapure water. The prepared ink was uniformly coated on the substrate with a four-side applicator, placed in a box furnace, heated to 200 °C, and sintered for 1 h to obtain the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating.

Simulation of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)

The full-wave simulation software was used to simulate the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating in this paper to study the effect of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) on electromagnetic waves. The Drude model is generally used to describe the dispersion properties of the material because \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) has the property of transitioning from a low-temperature insulating state to a high-temperature metallic state. The dielectric constant of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) is calculated as follows:

Where the high-frequency relative permittivity \(\varepsilon _{\infty }=12,\) the collision frequency constant \(\gamma =5.75\times 10^{13}\,\hbox{rad}/\hbox{s},\) and the plasma frequency \(\omega _{p}(\sigma )\) is related to the conductivity:

Where the reference conductivity \(\sigma _{0}=3\times 10^{5}\,\hbox{S}/\hbox{m}\) and the reference plasma frequency \(\omega _{p}\left( \sigma _{0}\right) =1.4\times 10^{15}\,\hbox{rad}/\hbox{s}\), \(\sigma _{\text{VO}_{2}}\) is the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) conductivity. The phase transition of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) materials with the temperature change was simulated by different conductivity values, and the dielectric constant of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) at different temperatures was obtained. As shown in Fig. 2 ,the phase transition of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) from an insulator to a metal between 45 and 55 °C is marked by a sharp increase in the imaginary part of the dielectric constant \((\varepsilon _{image}),\) indicating higher dielectric loss due to increased conductivity. Meanwhile, the real part \((\varepsilon _{real})\) decreases, reflecting reduced electrostatic energy storage capacity as \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) becomes metallic. These changes validate the suitability of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) for passive temperature sensing labels.

Characterization and testing of tungsten doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders and coatings

Characterization of tungsten doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders

As shown in Fig. 3, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the material before high-temperature annealing corresponds to the standard card PDF#31-1438, related to \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(B) prepared using the hydrothermal method. The intensity of the main peak before annealing was weak, and the peaks were slightly disordered. After annealing, the XRD pattern of the material became consistent with the standard card PDF#43-1051, as shown in Fig. 3. The crystalline shape of the material was transformed, and \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(M) was successfully prepared. The main peak after annealing was clear and sharp with high intensity, which significantly improved the crystallinity compared with that before annealing. There were no other heterogeneous peaks, indicating the formation of pure-phase \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)(M).

Figure 4 shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the material. The material as a whole was a large-sized bulk structure with a carambola-like structure composed of nanosheets and a number of spherical-like particles with an average particle size in the range of 4–6 \(\upmu\)m, with the largest being 10 \(\upmu\)m.

Pure-phase \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) has the phase transition capability from a low-temperature high-resistance state to a high-temperature low-resistance state. However, the excessively high phase transition temperature of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) compared to room temperature and human body temperature restricts its range of application. Therefore, it is necessary to dope the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder with tungsten to reduce the phase transformation temperature of the material. As shown in Fig. 5, the material was analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to discuss the chemical composition of tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder and the valence states of V and W elements in the sample.

Figure 5 shows the low-resolution XPS spectrum of tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder. It can be seen that the prepared tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder contained four elements, V, O, C, and W. Figure 5 shows the narrow range analyze of \(O1_{S}\) with a binding energy of around 530 eV. The fine spectrum of \(V2_{P}\) is shown in Fig. 5. It is observed that the characteristic peaks of \(V2_{P}\) were double peaks, and the peaks with binding energies of 516.48 and 523.77 eV belong to \(V2_{P3/2}\) and \(V2_{P1/2}\), respectively, which belong to the characteristic peaks of V4+. The two peaks with binding energies of 35.41 and 37.48 eV in Fig. 5 correspond to \(W4_{f5/2}\) and \(W4_{f7/2}\), respectively. According to the standard spectrum analyze, the tungsten element was in the form of +6 valence in the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder, proving that tungsten atoms replaced the vanadium atoms in the doping process.

Characterization of tungsten doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders

The differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) test curve of undoped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) is shown in Fig. 6. The phase transition temperature was 66.67 °C during the warming process, while the phase transition temperature was 60.24 °C during the cooling process. It can be seen that the thermotropic phase transition of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) was reversible, but there was a certain hysteresis phenomenon, and the thermotropic width was 6.43 °C. The phase transition temperature of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) decreased from 63.16 to 57.41 °C as the content of doped tungsten increased from 2 to 8 at%, as shown in Fig. 6. It shows that the tungsten atoms were successfully doped into \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\), and the phase transition temperature decreased gradually with the increase in the doping amount.

However, with the increase in the doping amount, the temperature width of the phase transition gradually widened, and the intensity of the enthalpy change decreased. This indicates that the doping of tungsten weakened the phase transition ability of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\). This is due to the substitution of doped tungsten atoms for the vanadium atoms, which destroyed the symmetry of the crystal structure. Based on the calculation results in Fig. 6, it was found that each 2 at% of tungsten doping reduced the phase transition temperature by only 3.6 °C6.

There may be two reasons, one is that the actual doping of tungsten is inefficient due to deviations in the solubility of reactants, material filling degree, reaction pressure, and ideal state; Secondly, the change in crystal structure of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) generated by hydrothermal treatment results in insufficient ability of tungsten doping to regulate the phase transition temperature. After repeated experiments, it was found that the phase transition temperature could be continuously reduced by adding more tungsten dopant into the hydrothermal precursor solution. Doping 18 at% tungsten could reduce the phase transition temperature to the body temperature range of humans or other mammals (36–38 °C).

The tungsten doping was controlled to be 18 at%, and the phase transition temperatures of these samples were tested and measured several times; the results are shown in Fig. 7. The phase transition temperatures of the four samples were 32.63, 36.81, 38.91, and 38.37 °C, most of the samples can be well controlled at 36–38 °C, and the temperature range was about 34–43 °C. According to the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) results in Fig. 7, the actual doping amount of tungsten was 5.5 at% at this time, and the phase transition temperature decreased by 5.2 °C for every 1 at% of tungsten atoms doped.

Testing of tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coatings

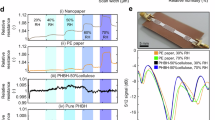

The preparation of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) ink begins by mixing terpineol and Triton, then heating and stirring the mixture until fully blended.The tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders were formulated with organic binder solutions in mass ratios of 60%, 80%, 100%, and 120% to formulate four inks while keeping the ethylcellulose content unchanged, and the results were tested as shown in Fig. 8. It can be seen that the magnitude of the change in the square resistance of the four samples before and after the phase transition is only 2–3 times, which is a large difference from the performance of the ideal \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) film. This difference may be caused by the following two factors: firstly, the particle size, crystallinity and purity of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) particles have an influence on their phase transition properties; secondly, the dispersion and stability of the ink system cannot be ensured by the chemical dispersion method alone, and large particles and agglomerates are still present in the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powders after high-temperature annealing. For this reason, an ultrasonic crusher was used to further crush and disperse the ink. Subsequently, the ultrasonic crushing-treated ink was uniformly coated on the quartz glass substrate and sintered to form a coating, as shown in Fig. 8.

Then, the square resistance of the prepared coating was measured by a four-probe tester. The coating was heated by a heating stage to analyze the relationship between the square resistance and temperature. As shown in Fig. 9, the square resistance of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating at room temperature decreased from 1003 to 90 \({\Omega }/{\square }\) after heating to 60 °C, which showed a significant decrease in the square resistance when compared with the sample that had not undergone ultrasonic crushing. For the cooling process, the square resistance increased from 90 to 973 \({\Omega }/{\square }\), with a significant hysteresis in the cooling process compared to the heating curve, and the maximum change occurred at 26–28 °C. The thickness of the coating was measured to be in the range of 0.18–0.21 \(\upmu\)m using a thickness gauge.

Design of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) based passive temperature sensing tags

Design and simulation analyze of unpatterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating

Electromagnetic waves need to be used to identify the designed temperature sensing tag to achieve passive temperature sensing. The electromagnetic scattering model contained Rayleigh, resonance, and optical regions in the frequency domain, where the resonance region contained the physical information of the target and, therefore, could be used as a signal to identify the target. The tag was attached to the target when the electromagnetic wave was incident on the surface of the label. The temperature information of the target was reflected in the backscattered signal through the temperature-sensitive characteristics of the tag, and the temperature of the target could be analyzed by processing the scattered signal of the tag.

When exposed to electromagnetic waves, the level of the signal reflected from the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) tag determined the sensing distance. The rate of changes in the level of the reflected signal from the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) tag determined the sensing accuracy. Therefore, the reflection coefficient (\(S_{11}\)) of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) tag was analyzed using full-wave simulation software by ANSYS. Figure 10 shows the unpatterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)-coated tag with the structure of a thin \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) film and a substrate; the thickness of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) was \(h_{2} = 0.2\) mm. Based on the measured square resistance and thickness of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating at 34–42 °C, the corresponding dielectric constant and loss tangent were calculated by the Drude model. The data were imported into the electromagnetic simulation software as the parameters of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) material. The substrate was made of quartz glass with a thickness of \(h_{1} = 0.5\) mm (\(\varepsilon _{\textrm{r}}=3.78, tan\delta \approx 0\)).

Figure 10 shows the \(S_{11}\) of the unpatterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating at the vertical incidence of Transverse Electric (TE)—and Transverse Magnetic (TM)—polarized electromagnetic waves, respectively. Port 1 was aligned to the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) surface, and Port 2 was aligned to the substrate. It can be seen that when the temperature increased from 34 to 40 °C, the \(S_{11}\) gradually decreased from \(-11.63\) to \(-7.20\) dB, but there was only a very small change in \(S_{11}\). This means that when the tag was irradiated by electromagnetic waves, the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) tag had a smaller discrimination in the reflection of electromagnetic waves at different temperatures, which is not conducive to fine-grained temperature sensing.

This is due to doping causing a deterioration in the phase transition of \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\), resulting in a decrease in the rate of change of conductivity with temperature, which leads to the fact that using only unpatterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) can only cause a weak response to the electromagnetic wave. The sensing and the analyze of the reflected signal became difficult. Thus, it was necessary to pattern the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating to respond to the electromagnetic wave with a large change in a specific frequency band, which facilitates temperature sensing.

Design and simulation analyze of patterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating

For these reasons, the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating was patterned and designed as a metasurface structure to improve the sensitivity of the reflection coefficient of the tag to temperature. The FSS was adopted as a metasurface structure. The FSS is being increasingly applied in various fields due to its excellent spatial filtering properties. The FSS unit structure was the cross- aperture type, as shown in Fig. 11; the design parameters are shown in Table 1. The designed patterned \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\)-coated structure was the same as the unpatterned one, with a quartz glass substrate with a 0.5 mm thickness and the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating with a 0.2 mm thickness.

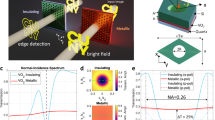

The patterned FSS unit structure based on \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) was simulated using the periodic boundary conditions method to demonstrate the necessity of a patterned design. Figure 10 shows the \(S_{11}\) of the FSS structure under different polarized wave incidences. For TE-polarized waves, resonance occurred at 4.30 GHz, with significant \(S_{11}\) variation in the 4–4.5 GHz range as temperature increased, and a gradual shift of the resonance frequency to lower frequencies. For TM-polarized waves, the temperature-dependent \(S_{11}\) curve was similar, indicating that the structure’s response remained stable across both polarizations, reflecting good polarization stability of the FSS structure.

To further analyze the electromagnetic response at different temperatures, results for both polarizations at 2.4 GHz, 4.3 GHz, and 5.2 GHz were examined. Table 2 show that \(S_{11}\) gradually increases with rising temperature under both polarizations. Specifically, at 4.30 GHz, as the temperature increases from 34 to 42 °C, \(S_{11}\) rises from \(-56.88\) dB and \(-42.28\) dB to \(-13.90\) dB and \(-14.17\) dB for TE and TM polarizations, respectively, showing a more substantial response to TE-polarized waves.

Figure 12 analyzes the variation curves of resonant frequency with temperature for the proposed FSS structure. As the temperature increased, the incident wave had the same change for both polarization modes, and the resonance frequency decreased linearly from 4.30 to 4.05 GHz.

The actual tag model was constructed using the FSS structure designed by unit simulation. At this point, the tag was simulated without using the periodic boundary condition method. The monostatic radar cross section (RCS) of the tag was simulated to discuss the effect of the tag on the intensity of electromagnetic wave reflection under temperature changes. Figure 13 shows the designed passive FSS sensing tag using a cellular structure arranged in an array of \(6\times 6\).

Figure 14 shows the variation of the monostatic RCS with temperature in the 2–6 GHz band range. When the temperature increased from 34 to 42 °C, the monostatic RCS increased gradually, in which the monostatic RCS increased from \(-31.63\), \(-28.28\), and \(-24.25\) dBsm to \(-26.24\), \(-22.98\), and \(-20.12\) dBsm at 2.4, 4.3, and 5.2 GHz respectively. On average, for every 1 °C increase in temperature, the RCS increased by approximately 0.56 dB. Figure 15 shows the variation of the monostatic RCS at 2.4, 4.3, 5.2, and 5.8 GHz for different temperatures with the change in incident angle. It can be seen that for these four frequency points, the monostatic RCS changed considerably with respect to temperature in a wide range of incidence angles. Therefore, the passive FSS temperature sensing tag had good sensitivity to temperature over a wide angular range.

The measurements based on vanadium dioxide passive temperature sensing tags

The prepared \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating was etched with periodic patterns by ion beam etching to obtain the FSS tag specimens; the processed tags are shown in Fig. 16.

Before the measurement, a copper metal substrate was placed in front of the horn antenna to determine the standard reflection coefficient. Then, the metal substrate was replaced by a passive temperature sensing tag, and the measurement results were compared with the standard reflection coefficient to get the normalized reflection coefficient. the experimental environment is shown in Fig. 17. Two horn antennas must be connected to Ports 1 and 2 of the vector network analyzer as the transmitter and receiver, respectively. Considering the difference in the antenna apertures and tag sizes, four FSS tags were pasted on the cardboard, as shown in Fig. 17. Finally, the label was placed on the heating table, and an infrared thermometer was used to measure the temperature of the label in real-time. Experimental data were recorded every 1 °C within the temperature range of 34–42 °C.

Figure 18 shows the measured normalized reflection coefficients. It can be seen that the reflection coefficients changed significantly over a wide frequency range (3.5–5.27 GHz) when the temperature was changed. As the temperature decreased from 42 to 34 °C, the reflection coefficient increased gradually, and the most obvious change was at 4.185 GHz, where the reflection coefficient increased from \(-29.04\) to \(-12.72\) dB. The reflection coefficient changed by 2.04 dB for each change of 1 °C on average, proving that the tag was feasible and highly accurate for temperature sensing. Meanwhile, there were some differences between the measured results and the simulation. This may be due to the following three reasons: first, the size of the passive temperature sensing tag was smaller than the horn antenna. Part of the electromagnetic wave bypassed the tag. Second, there were differences in the actual square resistance of different tags. The large granular tissue on the surface affected the etching process, resulting in poor patterning accuracy. Third, the measured results were affected by spatial multipath effects. The experimental environment was the laboratory room with an abundant multipath environment, and these multipath signals might impact the measured results.

Conclusion

This paper presented a passive temperature sensing patch based on tungsten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\), characterized by its low cost, battery-free, passive chipless, and accurate temperature sensing capabilities. Based on this insight, the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was prepared using the hydrothermal method. The phase transition temperature of the \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was reduced to 36–38 °C through tungsten doping. The tung sten-doped \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) powder was formulated into an ink, coated onto a quartz glass substrate, and sintered to produce a \(\hbox{VO}_{2}\) coating. The square resistance of this coating decreased from 1003 to 90 \({\Omega }/{\square }\) when heated from room temperature to 60 °C. A cross-aperture metasurface structure with polarization stability was designed using full-wave simulation software, and the coating was etched by an ion beam to enhance the changes in the reflection magnitude with the temperature variation. The experiment results indicated that in the frequency of 3.5–5.27 GHz, the reflection magnitude changed significantly as the temperature increased from 34 to 42 °C. The most notable change was observed at 4.185 GHz, where the reflection magnitude increased from \(-29.04\) to \(-12.72\) dB, achieving an average change of 2.04 dB per Celsius. It demonstrates the high accuracy and feasibility of the tag for temperature sensing. Therefore, this passive temperature sensing tag has great potential for practical applications, offering a cost-effective and reliable solution for temperature monitoring across various industries, especially human temperature sensing.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brandt, E. E., Roberts, K. T., Williams, C. M. & Elias, D. O. Low temperatures impact species distributions of jumping spiders across a desert elevational cline. J. Insect Physiol. 122, 104037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2020.104037 (2020).

Shajkofci, A. Correction of human forehead temperature variations measured by non-contact infrared thermometer. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 16750–16755. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3058958 (2022).

Liu, Y., Wen, J., Feng, Y., Huang, L. & Dong, J. Miniaturized high-sensitivity temperature sensor based on cascaded fiber-optic FPI. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 35, 430–433. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2023.3251412 (2023).

Lü, Y., He, X., Wei, Z.-H., Sun, Z.-Y. & Chang, S.-T. Ambient temperature-independent dual-band mid-infrared radiation thermometry. Appl. Opt. 55, 2169–2174. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.55.002169 (2016).

Vaz, A. et al. Full passive uhf tag with a temperature sensor suitable for human body temperature monitoring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 57, 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2010.2040314 (2010).

Guo, H., Wang, Y., Fu, H., Jain, A. & Chen, F. Influence of dopant valence on the thermochromic properties of \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 47, 21873–21881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.205 (2021).

Gomez-Heredia, C. L. et al. Measurement of the hysteretic thermal properties of W-doped and undoped nanocrystalline powders of \(\text{ VO}_{2}\). Sci. Rep. (2019).

Hong, B. et al. Dynamic strain control of the metal–insulator transition and non-volatile resistance switching in (010) \(\text{ VO}_{2}\)/(111) Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)0.7Ti0.3O3 epitaxial heterostructures. Mater. Lett. 196, 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2017.03.014 (2017).

Nakano, M. et al. Distinct substrate effect on the reversibility of the metal–insulator transitions in electrolyte-gated \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) thin films. Adv. Electron. Mater. 1, 321–330 (2015).

Gagaoudakis, E. et al. Low-temperature RF sputtered \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) thin films as thermochromic coatings for smart glazing systems. Sol. Energy 165, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.03.010 (2018).

Gao, Y. et al. Nanoceramic \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) thermochromic smart glass: A review on progress in solution processing. Nano Energy 1, 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2011.12.002 (2012).

Kim, M. S. et al. Simultaneous measurement of temperature and pressure using voltage-induced oscillation in vanadium-dioxide-based planar device. Sens. Actuators A 295, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2019.05.042 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. A novel vanadium dioxide-based dual-heater microfluidic thermal flow sensor with record high sensitivity. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 7244–7252. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3251662 (2024).

Kuzubasoglu, B. A. & Bahadir, S. K. Flexible temperature sensors: A review. Sens. Actuators A 315, 112282 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. A temperature sensor based on flexible substrate with ultra-high sensitivity for low temperature measurement. Sens. Actuators A 315, 112341 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Flexible temperature sensor with high sensitivity ranging from liquid nitrogen temperature to 1200 °C. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 5, 015601 (2022).

Su, Y. et al. Printable, highly sensitive flexible temperature sensors for human body temperature monitoring: A review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 15, 1–34 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. A thin-film temperature sensor based on a flexible electrode and substrate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 42 (2021).

Mikhail, et al. Vanadium dioxide as a natural disordered metamaterial: Perfect thermal emission and large broadband negative differential thermal emittance. Phys. Rev. X 3, 41004 (2013).

Zhiping et al. Infrared stealth property based on semiconductor (M)-to-metallic (R) phase transition characteristics of W-doped \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) thin films coated on cotton fabrics. Thin Solid Films (2014).

Mamun, M., Zhang, K., Baumgart, H. & Elmustafa, A. A. Evaluation of the nanomechanical properties of vanadium and native oxide vanadium thin films prepared by RF magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. (2015).

Cheikhou, et al. Fabrication of high-quality \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) thin films by ion-assisted dual AC magnetron sputtering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 5, 12520–12525 (2013).

Kim, C.-Y., Kim, S. H., Kim, S. J. & An, K.-S. \(\text{ VO}_{2}\)(110) film formation on tio2(110) through post-reduction of ALD grown vanadium oxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 313, 368–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.05.216 (2014).

Zhang et al.\(\text{ VO}_{2}\)(a) nanorods: One-pot synthesis, formation mechanism and thermal transformation to \(\text{ VO}_{2}\)(m). Ceram. Int. 44 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. New-phase \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) micro/nanostructures: Investigation of phase transformation and magnetic property. New J. Chem. 36 (2012).

Kong, F. Y., Li, M., Pan, S. S., Zhang, Y. X. & Li, G. H. Synthesis and thermal stability of W-doped \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) nanocrystals. Mater. Res. Bull. 46, 2100–2104 (2011).

Sidorov, A. I., Vinogradova, O. P., Lyubimov, V. Y. & Nashchekin, A. V. Synthesis and modification of micro-and nanorods of vanadium oxides. Tech. Phys. Lett. 34, 133–135 (2008).

Qi, J., Zhao, B., Yu, N., Niu, C. & Sun, G. G. Preparation of tungsten-doped \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) (m) nanoparticles through sol–gel method and hydrothermal synthesis. Adv. Mater. Res. 881–883, 960–963 (2014).

Greenberg, C. B. Undoped and doped \(\text{ VO}_{2}\) films grown from \(\text{ VO }(\text{ OC}_{3}\text{ H}_{7})_{3}\). Thin Solid Films 110, 73–82 (1983).

Sun, Z. et al. A miniaturized wireless passive frequency selective surface sensor for high-temperature applications. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 22734–22740. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3215518 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Shaanxi Science and Technology Innovation Team Program under Grant 2024RSCXTD05, the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi under Grant 2023-YBNY-049, the Science and Technology Project of Xi’an City under Grant 2024JH-CGKP-0003. (Corresponding authors: Fuwei Wang.)

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, F., Sun, R., Zhang, X. et al. Passive temperature sensing through chipless vanadium dioxide metasurface tags. Sci Rep 14, 31753 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82874-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82874-x