Abstract

Timely recognition and initiation of basic life support (BLS) before emergency medical services arrive significantly improve survival rates and neurological outcomes. In an era where health information-seeking behaviors have shifted toward online sources, chatbots powered by generative artificial intelligence (AI) are emerging as potential tools for providing immediate health-related guidance. This study investigates the reliability of AI chatbots, specifically GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Bard, and Bing, in responding to BLS scenarios. A cross-sectional study was conducted using six scenarios adapted from the BLS. Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) by United Medical Education. These scenarios covering adult, pediatric, and infant emergencies, were presented to each chatbot on two occasions, one week apart. Responses were evaluated by a board-certified emergency medicine professor from Tehran University of Medical Sciences, using a checklist based on BLS-OSCE standards. Correctness was assessed, and reliability was measured using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. GPT-4 demonstrated the highest correctness in adult scenarios (85% correct responses), while Bard showed 60% correctness. GPT-3.5 and Bing performed poorly across all scenarios. Bard achieved a correctness rate of 52.17% in pediatric scenarios, but all chatbots scored below 44% in infant scenarios. Cohen’s kappa indicated substantial reliability for GPT-4 (k = 0.649) and GPT-3.5 (k = 0.645), moderate reliability for Bing (k = 0.503), and fair reliability for Bard (k = 0.357). While GPT-4 showed the highest correctness and reliability in adult BLS situations, all tested chatbots struggled significantly in pediatric and infant cases. Furthermore, none of the chatbots consistently adhered to BLS guidelines, raising concerns about their potential use in real-life emergencies. Based on these findings, AI chatbots in their current form can only be relied upon to guide bystanders through life-saving procedures with human supervision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recognition of life-threatening situations and starting the proper basic life support (BLS) before Emergency Medical Service (EMS) arrives can save lives and improve neurologic outcomes and prognoses1. Organizations such as the American Heart Association (AHA), the Red Cross societies, and the Laerdal Foundation have been working globally to enhance the availability of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Automated External Defibrillator (AED) training2. However, in recent years, people’s health information-seeking habits have shifted to online and digital sources3. One of the most recent innovations in this area is generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots. These chatbots are virtual conversational agents that simulate human interactions using natural language processing systems4. They can offer immediate answers to health-related questions, recognize specific symptom patterns, and provide personalized recommendations for treatment plans based on individual symptoms and medical history5. A remarkable example of AI in CPR is an application that helps bystanders recognize out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and supports initiating bystander CPR during a call to the EMS dispatch center6,7. These AI tools have demonstrated high quality and empathy in their responses, sometimes outperforming physician-authored responses8. These AI tools have demonstrated high quality and empathy in their responses, sometimes outperforming physician-authored responses8. However, while specialized software can assist in such scenarios, the question remains whether widely-used chatbots like GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Bard, and Bing, designed for general purposes, possess this same capability. Research by Fijačko et al. demonstrated that ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, California, USA) responded well to BLS and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) examination questions, showing high relevance, accuracy, and alignment with resuscitation guidelines. This highlighted the potential of AI-powered chatbots to support healthcare professionals during critical scenarios, improving patient safety and optimizing outcomes9. Another study found that ChatGPT provided mostly accurate, relevant, and comprehensive responses to inquiries about cardiac arrest from survivors, their family members, and lay rescuers, although its responses related to CPR received the lowest ratings10. Similarly, research by Birkun revealed that Bing engaged effectively in meaningful conversations to assess simulated cardiac arrest situations and deliver CPR instructions, performing better than other web search assistants tested previously11. Conversely, Bard and Bing performed poorly in a separate study, with correct response rates of only 11.4% and 9.5%, respectively, raising concerns about potential harm if resuscitation instructions were not adequately followed12.

Trust and trustworthiness are central concepts in AI in medicine, encompassing factors like validity, reliability, safety, resilience, accountability, explainability, transparency, privacy, and fairness, especially in managing harmful biases13. These factors impact user perceptions of AI systems, and research is ongoing to explore how they affect trust in medical applications. The need for fairness in managing biases cannot be overstated, as it is critical for safe AI use in medicine. Furthermore, explainability in AI enhances accountability, particularly in high-stakes scenarios like BLS14. In these cases, the complexity and urgency of the situation demand that chatbots interpret rapidly changing information and provide accurate, actionable guidance. AI systems must be continuously monitored and evaluated to ensure patient safety.

The reliability of chatbots in some contexts15,16,17,18,19 was evaluated, but there is still a need to assess their reliability in responding to BLS prompts. Therefore, this study aims to assess the reliability of four widely-used AI chatbots, GPT-3.5, GPT-4, Bard, and Bing, in their ability to respond carefully crafted BLS scenarios designed to simulate real-life emergencies. These scenarios span a range of clinical contexts, covering adults, children, and infants. By subjecting the chatbots to these scenarios, we aim to evaluate their performance and highlight the importance of human oversight in such scenarios.

Method

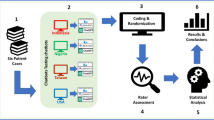

This cross-sectional study evaluated the reliability of responses from four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Bard, and Bing. Six scenarios adapted from the BLS Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) provided by United Medical Education (UME)20 were presented to each chatbot. These scenarios involved two adult, two pediatric, and two infant cases, with the first scene of each group focusing on a single rescuer, and the second on two rescuers Each scenario was rewritten in the first-person singular form, and the phrase “please teach me how to help him/her” was added to request instructional guidance. These scenarios are displayed in Table 1.

The chatbots were accessed using the Microsoft Edge web browser (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA) for Bing and the Google Chrome web browser (Google LLC; Mountain View, California USA) for Bard, ChatGPT-3.5, and ChatGPT-4. Browser histories and cookies were cleared before each scenario to eliminate potential bias. The scenarios were presented twice to each chatbot with a one-week interval between presentations. We assessed the responses using the previously mentioned OSCE standard UME checklists, which is why we employed a single rater. The evaluation was done by a board-certified professor of emergency medicine from Tehran University of Medical Sciences, an expert in AHA BLS guidelines. Each scenario had a particular checklist containing questions about scene safety, responsiveness check, call to EMS, request for AED, proper hand position in chest compression (CC), proper CC rate, proper CC depth, opening airway by maneuvers, rescue breaths, and AED use. Correct answers were marked as “Yes”, and incorrect ones were marked as “No”. The number of “yes” demonstrated the correctness of the chatbots’ responses. The rater was blind to the name of chatbots. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp.) to assess reliability.

Results

In adult scenarios, GPT-4 provided 85% correct answers (17 out of 20 questions) on its first attempt, followed by Bard with 60% correctness (12 out of 20 questions). The correctness rates for the other chatbots were below 50%. For pediatric scenarios, Bard provided 52.17% (12 out of 23 questions) on its second attempt, while all other chatbots scored below 44%. In infant scenarios, the correctness rate across all chatbots was less than 27% (23 questions). Bard’s second response was the most accurate overall, answering 42.42% of questions correctly (28 out of 66), followed by GPT-4’s first response, with 25 out of 66 (37.88%). Details of these data are presented in Table 2.

All chatbots correctly identified the BLS scenarios and proposed appropriate CPR sequences. However, only Bing could differentiate between one and two rescuers in infant scenarios, although it was not directly prompted. Bing’s recommendation to perform one minute of CPR before seeking additional help and retrieving an AED was inconsistent with AHA guidelines. Furthermore, although GPT-4, Bing, and Bard considered using an AED in adult scenarios, none of the chatbots advised bystanders to retrieve an AED if possible. The exact number of correct responses provided by each chatbot, categorized by question, can be found in Table 3.

Cohen’s kappa coefficient revealed substantial reliability forGPT-4 (k = 0.649,95% CI 0.460 to 0.837, p < 0.001), and GPT-3.5 (k = 0.645,95% CI 0.444 to 0.847, p < 0.001). Bing demonstrated moderate reliability (k = 0.503,95% CI 0.281 to 0.724, p < 0.001), while Bard showed fair reliability (k = 0.357,95% CI 0.143 to 0.570, p = 0.002). The kappa values for each chatbot across different scenarios are detailed in Table 4.

Discussion

This study evaluated the correctness and reliability of responses from four chatbots in BLS scenarios. GPT4 showed the best performance in adult BLS scenarios, with an 85% correctness but had weaker performance in pediatric and infant scenarios. Bard demonstrated relatively acceptable performance in adult BLS scenarios, with a 60% correctness, but like GPT-4, struggled in pediatric and infant cases. Bing and GPT-3.5 did not meet expectations, particularly in pediatric and infant emergency scenarios, raising concerns about the adequacy of current AI models for high-stakes medical decision-making. The study’s findings emphasize that while GPT-4 performed adequately in adult BLS scenarios, it and the other chatbots displayed significant weaknesses in pediatric and infant emergency cases. This suggests that generative AI models, as they currently stand, may not be suitable for life-critical scenarios involving younger patients. These findings resonate with prior research highlighting the complexity of pediatric and infant BLS protocols, which require precise adjustments based on age and physiological differences. The lower correctness rates observed in these groups may be attributed to the chatbots’ limitations in understanding these nuanced requirements, as their training data may have been primarily based on adult scenarios or non-clinical conversations.

Results of a study on GPT4, GPT3.5, Bard, and Microsoft Copilot (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) as a newer version of Bing showed that the accuracy of answers of these chatbots to the pre-course Advanced Life Support (ALS) Multiple Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) was 87.5%, 42,25%, 57.5% and 62.5% respectively21. Zhu et al. also tried to check GPT’s ability to pass the BLS-ACLS exams of AHA22. They found that the accuracy of GPT in the BLS exam was 84% and increased to 96% using open-ended questions for incorrect answers. However, in scenario-based prompts, the performance of chatbots changes. Bushuven et al. reported that ChatGPT provided only 40% correct medical advice in a pediatric choking case23. They found that ChatGPT provided accurate first-aid guidance in only 45% of cases. Birkun et al. showed that Bing and Bard performed poorly in the scenario of non-breathing victims. The alignment of responses with guideline-consistent instructions was inadequate, with the average percentage of completely satisfactory answers being 9.5% for Bing and 11.4% for Bard12. The study found that the chatbots’ responses were aligned with the AHA’s BLS guidelines. For example, all chatbots could identify BLS scenarios; most of them checked the victim’s responsiveness and recommended calling EMS. However, it is essential to note that the chatbots’ responses lacked specific life-saving advice, such as not advising bystanders to bring and use an AED or providing instructions for proper hand position during chest compression and the appropriate rate and depth of CPR. This could significantly undermine the trustworthiness of the chatbot. This misconception of chatbots was highlighted in a study where none of the responses concerning instructions to use AED, monitoring a person’s breathing and responsiveness, and starting CPR were entirely satisfactory24.

Another important consideration raised by this study is the concept of trust in AI systems, particularly in high-stakes environments like BLS. Trustworthiness is determined by the accuracy of the information and the AI’s reliability, transparency, and explainability—factors that were inconsistent across the chatbots tested. For example, GPT-4 showed substantial reliability, yet its failure in some scenarios suggests that users may be unable to trust it fully in critical situations. Of course, while these kappa values suggest varying levels of response reliability, they do not inherently attest to the chatbots’ usefulness; for instance, GPT-3.5 demonstrated complete consistency in adult scenarios, yet only 25% of its answers were correct. Similarly, Bing’s agreements were high in specific scenarios, but its correct response rates were 21.74% and 8.7%, indicating reliable but incorrect responses. Walker et al. did assess GPT-4 reliability in hepatic-pancreatic-biliary (HPB) conditions, finding 60% accuracy and substantial agreement (k = 0.78, p < 0.001)25. However, some studies state that chatbots cannot provide reliable answers in managing clinical scenarios; therefore, they must be developed to be reliable assistants for physicians15,19. One solution to increasing trust in artificial intelligence, especially in medicine, is to move towards explainable AI, which is being researched in new studies. In these AI, the decision-making path and results can be tracked and evaluated, unlike AI such as GPT, whose results are obtained from a black box. These findings align with the decisions mentioned in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights. Artificial intelligence can only be used in clinical decision-making for diagnosis or treatment with human supervision and oversight. Even if it is used as an assistant, the patient should be informed and even given informed consent26.

Limitations of the study

It is essential to acknowledge the limitations of our study. The small sample size, consisting of only six scenarios presented twice, may restrict the generalizability of our findings. Future studies should encompass broader BLS scenarios for a more comprehensive evaluation. Additionally, the use of the English language in our prompts can limit the results of this study to English-speaking people. Checking the accuracy and reliability of chatbots in other languages can be evaluated in future studies.

Future directions

Future research should prioritize training chatbots using larger datasets tailored to pediatric and infant BLS protocols to enhance their performance in these areas. Additionally, developing chatbot architectures specifically tailored for healthcare information retrieval and decision-making could enhance the accuracy and consistency of BLS instructions. Future studies could compare general-purpose AI tools like GPT-4, Bard, and Bing with those specifically designed for medical contexts to determine whether domain-specific AI systems offer better performance in BLS and other emergency scenarios.

Real-world applications

Integrating chatbots with high accuracy in BLS into smartphone applications or wearable devices could provide real-time guidance to bystanders during emergencies. Continued research and development may lead to the implementation of chatbots capable of offering BLS support and addressing user queries in emergencies. In essence, thorough evaluation and continuous improvement of AI chatbots are pivotal to ensuring their reliability in BLS scenarios, ultimately enhancing patient safety and optimizing patient outcomes. However, based on ethical and legal principles, these popular chatbots may not currently be advisable in medical real-world applications.

Conclusion

While GPT-4 showed the highest correctness and reliability in adult BLS situations, all tested chatbots struggled significantly in pediatric and infant cases. Furthermore, none of the chatbots consistently adhered to BLS guidelines, raising concerns about their potential use in real-life emergencies. Based on these findings, AI chatbots in their current form can only be relied upon to guide bystanders through life-saving procedures with human supervision.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Blewer, A. L. et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training disparities in the United States. J. Am. Heart Association. 6 (5), e006124 (2017).

Bray, J. E. et al. Public cardiopulmonary resuscitation training rates and awareness of hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross‐sectional survey of victorians. Emerg. Med. Australasia. 29 (2), 158–164 (2017).

Mirzaei, A., Aslani, P., Luca, E. J. & Schneider, C. R. Predictors of health information–seeking behavior: systematic literature review and network analysis. J. Med. Internet. Res. 23 (7), e21680 (2021).

Ivanovic, M. & Semnic, M. (eds) The role of agent technologies in personalized medicine. 2018 5th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI); : IEEE. (2018).

Tripathy, A. K., Carvalho, R., Pawaskar, K., Yadav, S. & Yadav, V. (eds) Mobile based healthcare management using artificial intelligence. International Conference on Technologies for Sustainable Development (ICTSD); 2015: IEEE. (2015).

Byrsell, F. et al. Machine learning can support dispatchers to better and faster recognize out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during emergency calls: a retrospective study. Resuscitation 162, 218–226 (2021).

Blomberg, S. N. et al. Effect of machine learning on dispatcher recognition of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during calls to emergency medical services: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. open. 4 (1), e2032320–e (2021).

Ayers, J. W. et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 183 (6), 589–596 (2023).

Fijačko, N., Gosak, L., Štiglic, G., Picard, C. T. & Douma, M. J. Can ChatGPT pass the life support exams without entering the American heart association course? Resuscitation ;185. (2023).

SCQUIZZATO, T. et al. Testing ChatGPT ability to answer frequently asked questions about cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. (2023).

Birkun, A. Performance of an artificial intelligence-based chatbot when acting as EMS dispatcher in a cardiac arrest scenario. Intern. Emerg. Med. 18 (8), 2449–2452 (2023).

Birkun, A. A. & Gautam, A. Large Language Model (LLM)-powered chatbots fail to generate guideline-consistent content on resuscitation and may provide potentially harmful advice. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 38 (6), 757–763 (2023).

Chen, F., Zhou, J., Holzinger, A., Fleischmann, K. R. & Stumpf, S. Artificial Intelligence ethics and trust: from principles to practice. IEEE. Intell. Syst. 38 (6), 5–8 (2023).

Longo, L. et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) 2.0: a manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Inform. Fusion. 106, 102301 (2024).

Goodman, R. S. et al. Accuracy and reliability of chatbot responses to physician questions. JAMA Netw. open. 6 (10), e2336483–e (2023).

Kasthuri, V. S. et al. Assessing the accuracy and reliability of AI-Generated responses to patient questions regarding spine surgery. JBJS :102106. (2021).

Schick, A., Feine, J., Morana, S., Maedche, A. & Reininghaus, U. Validity of chatbot use for mental health assessment: experimental study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 10 (10), e28082 (2022).

Amaro, I., Della Greca, A., Francese, R., Tortora, G. & Tucci, C. (eds) AI unreliable answers: A case study on ChatGPT. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; : Springer. (2023).

Platz, J. J., Bryan, D. S., Naunheim, K. S. & Ferguson, M. K. Chatbot Reliability in Managing Thoracic Surgical Clinical Scenarios (The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 2024).

Education, U. M. BLS Skills Checklist Download, accessed 5 December 2023, (2019). https://www.acls-pals-bls.com/bls-skills-session-test-with-checklist/ [.

Semeraro, F., Gamberini, L., Carmona, F. & Monsieurs, K. G. Clinical questions on advanced life support answered by artificial intelligence. A comparison between ChatGPT, Google Bard and Microsoft Copilot. Resuscitation ;195. (2024).

Zhu, L., Mou, W., Yang, T. & Chen, R. ChatGPT can pass the AHA exams: open-ended questions outperform multiple-choice format. Resuscitation 188, 109783 (2023).

Bushuven, S. et al. ChatGPT, can you help me save my child’s life?-Diagnostic accuracy and supportive capabilities to lay rescuers by ChatGPT in prehospital Basic Life Support and Paediatric Advanced Life Support cases–an in-silico analysis. J. Med. Syst. 47 (1), 123 (2023).

Birkun, A. A. & Gautam, A. Large language model-based chatbot as a source of advice on first aid in heart attack. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. :102048. (2023).

Walker, H. L. et al. Reliability of medical information provided by ChatGPT: assessment against clinical guidelines and patient information quality instrument. J. Med. Internet. Res. 25, e47479 (2023).

Stöger, K., Schneeberger, D. & Holzinger, A. Medical artificial intelligence: the European legal perspective. Commun. ACM. 64 (11), 34–36 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hadi Mirfazaelian for helping us with statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saeed Aqavil-Jahromi Conceptualized the objections and methodology of the article. Mohammad Eftekhari carried out Data curation and formal analysis. Mehrnoosh Aligholi-Zahraie wrote the original draft. Hamideh Akbari reviewed and edited the article. Saeed Aqavil-Jahromi took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study did not use human data and according to Iranian regulations, no ethical approval was required for it.

Content of publication

While preparing this work, the authors used ChatGP4 and ChatGPT3.5 to improve readability, text integrity, and language grammar. After using this, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aqavil-Jahromi, S., Eftekhari, M., Akbari, H. et al. Evaluation of correctness and reliability of GPT, Bard, and Bing chatbots’ responses in basic life support scenarios. Sci Rep 15, 11429 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82948-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82948-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Artificial intelligence to improve patient care in emergency medicine: a workflow-based analysis

Internal and Emergency Medicine (2025)