Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the correlation between baseline MRI features and baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) expression status in rectal cancer patients. A training cohort of 168 rectal cancer patients from Center 1 and an external validation cohort of 75 rectal cancer patients from Center 2 were collected. A nomogram was constructed based on the training cohort and validated using the external validation cohort to predict high baseline CEA expression in rectal cancer patients. The nomogram’s discriminative ability and clinical utility were tested using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and decision curve analysis (DCA). The baseline CEA high-expression group had significantly higher MRI-detected metastatic lymph node (mLN), MRI-detected extramural vascular invasion (mEMVI), infiltrating tumor border configuration (iTBC), peritoneal invasion, annular infiltration, maximum extramural depth (MED), and tumor length than the normal CEA group (P < 0.05). Among them, MED [odds ratio (OR):1.19 (1.03–1.38), P = 0.016] and annular infiltration [OR:2.36 (1.06–5.25), P = 0.036] were independently predicting factors for high baseline CEA expression. The trained and validated model for predicting high baseline CEA expression in the training and external validation cohorts had the area under the curves (AUC) of 0.787 (95% CI 0.716–0.859) and 0.799 (95% CI 0.698–0.899), respectively. The calibration curves of both cohorts demonstrated good agreement between predicted and observed outcomes. Decision curve analysis indicated the clinical value of the nomogram. We developed a visual nomogram to predict high baseline CEA expression for patients with rectal cancer, enabling clinicians to conduct a personalized risk assessment and therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most prevalent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with rectal cancer (RC) accounting for approximately one-third of these cases1,2. Despite the significant benefits of various treatment modalities, including surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, the survival rate for locally advanced rectal cancer remains unsatisfactory, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 12%3,4. Therefore, further research is needed to identify prognostic markers for better assessment of disease progression in colorectal cancer. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is associated with cell adhesion and metastasis in colorectal cancer5,6,7. It plays a role in intercellular recognition, diffusion, and proliferation, and facilitates the adhesion of colorectal cancer tumor cells to metastatic sites. CEA levels have been shown to predict poor prognosis, recurrence, and response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients8,9,10. In our previous research, we have identified certain MRI characteristics of primary rectal tumors that are associated with recurrence and metastasis11. Consequently, we hypothesize that these MRI features of primary tumors, which correlate with poor prognostic indicators, may also be associated with an initially high expression of CEA. Consequently, the objective of this study is to explore the MRI features associated with high baseline expression of CEA in rectal cancer. By identifying readily accessible biomarkers detected by MRI of baseline serum CEA expression, this research may facilitate the screening of high-risk rectal cancer patients characterized by aggressive tumor behavior and a propensity for distant metastasis. Such findings could contribute to implementing earlier intervention strategies and developing more precisely tailored treatment methodologies.

Materials and methods

Patients

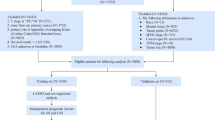

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital and Tai’an City Central Hospital, and the requirement for informed consent was waived. We assembled a training cohort of 168 patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma based on histopathological examination at Beijing Friendship Hospital (center 1) from 2015 to 2019. Additionally, an external validation cohort of 75 patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma at Tai’an City Central Hospital (center 2) from 2017 to 2022 was collected. MRI scans were performed for all patients before surgery. The exclusion criteria were the following: (i) patients without total mesorectal excision; (ii) patients with incomplete magnetic resonance imaging images or clinicopathologic data; (iii) patients with more than one week between baseline MRI and initial CEA; (iv) patients whose baseline MRI and CEA were performed after neoadjuvant therapy; (v) patients with concurrent other malignancies. The final inclusion included 168 patients in the training cohort and 75 patients in the external validation cohort (Fig. 1). In the training cohort, there were 16 cases of synchronous metastasis (including 9 liver metastases, 2 simultaneous liver and lung metastases, 4 pulmonary metastases, and 1 sacral bone metastasis). Additionally, in this cohort, 27 cases received preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. In the external validation cohort, there were 8 cases of synchronous metastasis (including 7 liver metastases and 1 pulmonary metastasis). Additionally, in this cohort, 9 cases received preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. Due to social and economic reasons in our country, the rate of preoperative neoadjuvant therapy among rectal cancer patients at our two centers was not high.

MRI technique

MRI scans were conducted using two 3.0T systems: the GE Signa Excite HD 3.0T and the Siemens Magnetom Skyra 3.0T. Each system had an 8-channel and a 16-channel body surface coil, respectively. Before the scan, patients were instructed to adhere to a light diet for 24 h. Antispasmodic drugs were not administered before the MRI scan, but an enema was performed. Sagittal high-resolution T2-weighted imaging (HRT2WI), oblique axial HRT2WI, and oblique coronal HRT2WI sequences were all acquired with a slice thickness of 3 mm and a gap of 0.5 mm, without fat saturation. The oblique axial HRT2WI sequence was oriented perpendicular to the long axis of the affected bowel segment, covering the entire tumor. Conversely, the oblique coronal HRT2WI sequence was aligned parallel to the long axis of the diseased bowel segment, encompassing the entire tumor as well as the anterior and posterior walls of the rectum. The sagittal HRT2WI sequence was acquired perpendicular to the intestinal lumen, covering both lateral walls of the rectum.

Imaging interpretation

Two radiologists, one with 10 years and the other with 21 years of clinical experience in abdominal MRI diagnosis, conducted a retrospective analysis of MRI data for all patients. They were familiar with the diagnostic criteria and would engage in discussions to resolve any disagreements that arose. If the disagreements persisted, a third experienced gastrointestinal radiologist would be brought in for further consultation until a consensus was reached. None of the radiologists were aware of the pathological results for the patients.

Based on Smith’s 5-point rating system12, mEMVI negative was diagnosed with a score of 0 to 2, while mEMVI positive was determined with a score of 3 to 4. Pelvic nodules that showed high signal on high b-value DWI were classified as mLN13 if they met either of the following two criteria on HRT2WI: (i) nodules with a short diameter greater than or equal to 1.0 cm; (ii) nodules with a short diameter less than 1 cm exhibited significant internal signal heterogeneity, rough or lobulated margins. Primary lesions of rectal cancer could grow in two distinct patterns: annular infiltration, where the tumor extended in a circular or semi-circular manner along the rectal wall (Fig. 2A), and localized mass growth, characterized by a round or oval shape. When the primary lesion was confined within a limited area and had an irregular shape, but its maximum width was greater than half of its length, it was also considered as localized mass (Fig. 2B and C). Referring to the histopathological concept of TBC14, we classified the MRI tumor border morphology into iTBC and pushing TBC (pTBC). iTBC was characterized by multiple nodules or cords of varying sizes at the margin of the primary tumor, exhibiting irregular and rough boundaries (Fig. 2C and D). On the other hand, pTBC was characterized by clear boundaries of the primary tumor or the presence of a single smoothly-bordered nodular protrusion, or uniformly thick and well-defined cords at the tumor margin (Fig. 2B).

A: The primary lesion of rectal cancer demonstrates circumferential wall infiltration. B: A morphologically irregular, lobulated, focal soft tissue mass is observed in the left posterior wall of the rectum. The mass predominantly protrudes into the lumen, with clear lesion boundaries. It is categorized as a localized mass and pTBC. C: An irregular mass is observed in the right wall of the rectum, with multiple uneven and rough border indistinctive strands (white arrow) seen on its right edge. The growth pattern is classified as localized mass and iTBC. D: Axial HRT2WI shows multiple small nodular projections (white arrow) along the edge of a round-shaped primary cancer lesion. These nodules exhibit rough margins, and irregular small strands are observed near the margins. It is classified as iTBC.

MED was assessed by measuring the vertical distance from the most distal point of the tumor to the residual intrinsic muscle layer in the area of the tumor on oblique axial HRT2WI. Tumor length was measured along the longitudinal axis of the affected intestine at multiple points within the upper and lower boundaries of the tumor. According to the extent of tumor infiltration into the intestinal wall, the circumferential extent is classified into three groups: ≤1/3, 1/3 − 2/3, and ≥ 2/3. According to the distance between the lower edge of the primary tumor in the rectum and the anus, the tumor location is classified into lower (≤ 5 cm) and mid-upper (> 5 cm).

Clinicopathological assessment

The surgical samples were preserved in a 10% formalin solution for over 48 h. They were then sectioned both horizontally and vertically along the longitudinal axis of the rectum at a thickness of 3 micrometers. Histopathological examination evaluated and documented various parameters such as pathology-proven extramural vascular invasion (pEMVI), pathology-proven lymph node metastasis (pLN), degree of differentiation, and adenocarcinoma subtypes. A highly skilled pathologist specializing in colorectal pathology performed the histopathological examination. CEA collected within one week of the baseline MRI were categorized into two groups: normal (≤ 5 ng/ml) and high expression (> 5 ng/ml).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests used in this study were performed using SPSS 26.0 and R4.2.1. The normality of the continuous data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and the differences between the two groups were analyzed using an independent samples t-test. The results were reported as the median [interquartile range (IQR)] for non-normally distributed data, and the differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were presented as n (%), and the differences between the two groups were assessed using the Chi-square test. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and a significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the observed differences.

First, a univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the impact of diagnostic factors such as age, gender, and mLN. Subsequently, a stepwise regression (backward method) was performed using binary logistic regression to select the optimal predictor variables for the final model. Second, a calibration plot was used to assess the calibration. Third, based on binomial logistic regression analysis results, the R software implemented the nomogram to predict the risk of high baseline CEA in the training cohort. This nomogram underwent rigorous internal validation via Bootstrap resampling and external validation. The ROC curve assessed its discriminative ability, and DCA evaluated its clinical utility. In our model, the risk of high baseline CEA expression was quantified probabilistically, ranging from 0 (highly unlikely) to 1 (highly probable).

Results

.

Patient characteristics

A total of 243 patients (150 males and 93 females) with rectal cancer were enrolled in this study. The mean age of these patients was 64.0 ± 10.5 yrs. 65.6 ± 10.6 yrs for training cohort patients and 64.9 ± 10.2 yrs for female patients. The baseline characteristics of the training and external validation cohorts were in Table 1. There were statistically significant differences in TBC, tumor location, pEMVI, pLN, growth pattern, MED, and CEA between the training cohort and the external validation cohort.

Univariable and stepwise multivariable regression analysis for CEA

Univariate analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the variables mLN, mEMVI, TBC, nodular protrusion or mLN on the posterior wall, peritoneal invasion, circumferential extent, pEMVI, growth pattern, subtypes of adenocarcinoma, MED, and tumor length between the high expression and normal groups of CEA (Table 2). After conducting stepwise multivariable regression analysis, MED [OR: 1.19 (1.03–1.38), P = 0.016] and annular infiltration [OR: 2.36 (1.06–5.25), P = 0.036] were identified as independent predictors of high baseline CEA expression (Table 2).

Construction and validation of the nomograms

The nomogram (Fig. 3) was developed to predict high baseline CEA expression in the training cohorts using the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis. The nomogram went through internal verification by Bootstrap self-sampling and external validation. The AUC of the nomograms in the training and external validation cohorts were 0.787 (0.716–0.859) and 0.799 (0.698–0.899), respectively. Calibration curves analysis (Fig. 4A and D) revealed a strong correlation between predicted and actual outcomes. The ROC curves (Fig. 4B and E) exhibited satisfactory discriminative ability, and the DCA (Fig. 4C and F) demonstrated good clinical utility.

Nomogram for predicting expression status of initial CEA. For a rectal cancer patient with a primary tumor displaying annular infiltration and a maximum extramural depth (MED) of 16 mm, the total score for this patient is approximately 80 (18 + 62). Consequently, the risk of high CEA expression for this patient at this stage is approximately 87%.

Predictive performance of MRI indicators and nomograms for CEA

The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and AUC of the nomogram predicting high baseline CEA expression in the training cohort were 70.0%, 78.7%, 75.6%, and 0.787 (0.716–0.859), respectively (Table 3). The AUC of the external validation cohort was 0.799 (0.698–0.899), which was higher than that of the training cohort with a value of 0.787(0.716–0.859) and MED with a value of 0.775 (0.702–0.847) (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study was one of the few articles that explored the correlation between MRI features of rectal cancer and baseline serum CEA expression. In our study, we retrospectively collected MRI and clinical pathological data of patients with rectal cancer to demonstrate that the growth pattern and depth of infiltration of the primary tumor in rectal cancer can predict the baseline expression status of CEA in these patients. These MRI features serve as readily accessible and cost-effective clinical tools that can assist clinicians in distinguishing patients with invasive tumors.

Our study found that MED and annular infiltration were independent predictive factors for high baseline serum CEA expression. For every 1 mm increase in MED of the primary tumor, the likelihood of high baseline CEA expression in the patient increased by 1.19 times. MED reflected the size of the primary tumor and its invasive capacity in rectal cancer. A larger MED indicated a larger tumor volume and higher T stage, indicating a stronger invasion and infiltration at the margins of the primary tumor. Simultaneously, larger tumors are associated with increased production of CEA. Tong et al.15similarly found a correlation between larger MED, higher CEA expression, and lymph node metastasis, which is consistent with some of the findings from our study. Several studies have confirmed that larger MED is often associated with poorer prognosis11,16,17and is related to extramural vascular invasion11, local recurrence and distant metastasis11,17. In addition to the tumor, all these metastatic lesions can produce CEA, leading to high baseline CEA levels, thereby supporting our research findings. Studies have shown that higher levels of CEA are associated with advanced N/M staging and larger tumor volume18,19. These findings are consistent with our research findings, where we also observed a correlation between high baseline CEA expression and the extent of rectal wall invasion, MED, tumor length, and tumor growth pattern. Previous studies have found that CEA is also involved in tumor cell proliferation, modulation of the sinusoidal microenvironment, and stimulation of tumor angiogenesis20, resulting in accelerated tumor growth and increased tumor volume, which may serve as the pathological molecular basis of our research findings.

Additionally, rectal cancer patients with annular infiltration had 2.36 times higher chances of developing high baseline CEA expression compared to patients with localized mass growth. Rectal primary lesions with annular infiltration had a larger volume and surface area. This may result in the primary lesion coming into contact with and infiltrating a greater number of lymph nodes, blood vessels, and surrounding rectal tissue structures. Consequently, there is a higher likelihood of multiple metastases occurring, leading to increased production of CEA from both the primary and metastatic lesions. Additionally, we further analyzed the association between iTBC and annular infiltration using Chi-square tests. Observational results demonstrated that among 72 cases of rectal primary lesions with tumors in the form of iTBC in the training cohort, annular infiltration was exhibited in 55 of these cases, accounting for 76.4% (P< 0.05), suggesting a close correlation between the two variables. It is worth noting that rectal cancers with iTBC display lower immune responses21,22, and iTBC was associated with increased tumor size and conventional adenocarcinoma, high tumor budding and low tumor stroma ratio23. This suggests that iTBC and annular infiltration may indicate a higher invasive capability of such rectal primary lesions.

The presence of mLN, mEMVI, and pEMVI indicates the occurrence of distant metastasis through the lymphatic and vascular systems. These distant metastatic lesions can also contribute to the production of CEA. CEA has been extensively studied and its involvement in cancer cell adhesion and metastasis has been well-documented24,25. This may provide a pathological and molecular basis for the observed correlation between high baseline serum CEA expression and the presence of peritoneal invasion, iTBC, annular infiltration, mLN, mEMVI, and pEMVI in our study. In addition to promoting distant metastasis, EMVI may potentially facilitate the direct release of tumor-derived CEA into the intravascular space through compromised blood vessels. This mechanism could plausibly contribute to the observed high expression of mEMVI, pEMVI, and baseline serum CEA in our study.

The nomogram constructed based on the training cohort was well-validated in the external validation cohort. Additionally, our MRI scanning sequences belong to conventional rectal imaging sequences, featuring easily accessible and intuitive observation indicators. These characteristics may provide more practical assistance to clinicians and radiologists. It is worth noting, however, that there are statistical differences in multiple indicators, such as TBC, growth pattern, pEMVI, and MED, between the two centers as shown in Table 1, which may be related to sample differences between them. Center 1, located in Beijing, the capital of China, is a top-tier tertiary comprehensive hospital with significantly higher diagnostic and treatment capabilities than Center 2, and it serves a large number of patients from across China. In contrast, Center 2 is a regional tertiary comprehensive hospital with moderate diagnostic and treatment capabilities, serving a relatively smaller number of patients mainly from the Tai’an area. Moreover, the economic development of this region lags behind Beijing. Therefore, factors such as diagnostic and treatment capabilities, geographical location, and economic development of the two centers may have contributed to the sample differences observed.

Indeed, there are some limitations in our study. Firstly, we acknowledge that the current study provides limited direct assistance to clinicians; we have merely uncovered some correlations between MRI features and high baseline CEA expression. Furthermore, due to the fact that CEA levels can be elevated in various situations, including smoking, as well as benign and malignant diseases, the specificity of CEA in diagnosing and assessing rectal cancer is not strong. Moreover, CEA values fluctuate during different stages of the disease. Perhaps in future studies, we should consider raising the threshold for high baseline CEA expression to > 13.0 ng/ml10 or analyze the dynamic changes of CEA with shorter intervals to baseline MRI. By doing so, the results of our study on rectal cancer MRI characteristics are likely to be more persuasive. Secondly, it is worth noting that a significant interval between the MRI and total mesorectal excision exists for certain patients. This extended duration has the potential to alter the tumor status and consequently impact the assessment of certain indicators. Thirdly, despite being a multicenter study, the sample size remained relatively small, and there was also a bias in the samples from the two centers. Fourthly, although this study has an external validation cohort, and the training cohort model has been well validated by the external validation cohort, there are technical and regional differences between the two hospitals, which are Center 1 and Center 2, which resulted in statistical differences in several indicators across the two cohorts. Lastly, this study is a retrospective study, and precise matching between baseline mEMVI, mLN, and postoperative pEMVI and pLN could not be achieved. In addition, some patients in this study underwent preoperative neoadjuvant therapy, which resulted in a long interval between baseline CEA and postoperative pathology in these patients, which was sufficient for tumor progression, resulting in postoperative pathology that could not reflect the real status of rectal cancer lesions at the stage of baseline CEA.

Conclusion.

Our study found that primary lesions of rectal cancer with larger MED and annular infiltrative growth tend to have high baseline serum CEA expression. A visual nomogram based on MRI features for predicting high baseline CEA expression in patients with rectal cancer may aid in identifying those with rapid tumor growth and a propensity for distant metastasis.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen.

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic.

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis.

- mLN:

-

MRI-detected metastatic lymph node.

- mEMVI:

-

MRI-detected extramural vascular invasion.

- iTBC:

-

infiltrating tumor border configuration.

- MED:

-

maximum extramural depth.

- OR:

-

odds ratio.

- AUC:

-

area under the curve.

- CRC:

-

colorectal cancer.

- RC:

-

rectal cancer.

- HRT2WI:

-

high resolution T2-weighted imaging.

- pTBC :

-

pushing tumor border configuration.

- PEMVI:

-

pathology-proven extramural vascular invasion.

- pLN :

-

pathology-proven lymph node metastasis.

- IQR:

-

interquartile range.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72 (1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21708 (2022).

Siegel, R., DeSantis, C. & Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 64 (2), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21220 (2014).

Benson, A. B. et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colon Cancer, Version 2.2018. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 16 (4), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0021 (2018).

Bramswig, K. H. et al. Prager. Soluble carcinoembryonic antigen activates endothelial cells and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 73 (22), 6584–6596. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0123 (2013).

Beauchemin, N. & Arabzadeh, A. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules(CEACAMs) in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 32 (3–4), 643–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-013-9444-6 (2013).

Bajenova, O. et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen promotes colorectal cancer progression by targeting adherens junction complexes. Exp. Cell. Res. 324 (2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.04.007 (2014).

Qian, X., Wang, H., Ren, Z., Jin, F. & Pan, S. Y. The value of NLR, FIB, CEA and CA19-9 in colorectal cancer. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 55 (4), 499–505 (2021).

Lakemeyer, L. et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of CEA and CA19-9 in Colorectal Cancer. Diseases 9 (1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases9010021 (2021).

Cai, H., Chen, Y., Zhang, Q., Liu, Y. & Jia, H. High preoperative CEA and systemic inflammation response index (C-SIRI) predict unfavorable survival of resectable colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 21 (1), 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-023-03056-z (2023).

Lv, B. et al. Predictive value of lesion morphology in rectal cancer based on MRI before surgery. BMC Gastroenterol. 23 (1), 318. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02910-4 (2023).

Smith, N. J., Shihab, O., Arnaout, A., Swift, R. I. & Brown, G. MRI for detection of extramural vascular invasion in rectal cancer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 191 (5), 1517–1522. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.08.1298 (2008).

Kim, J. H., Beets, G. L., Kim, M. J., Kessels, A. G. & Beets-Tan, R. G. High-resolution MR imaging for nodal staging in rectal cancer: are there any criteria in addition to the size? Eur. J. Radiol. 52 (1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.005 (2004).

Jass, J. R. et al. Assessment of invasive growth pattern and lymphocytic infiltration in colorectal cancer. Histopathology 28 (6), 543–548. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-467.x (1996).

Tong, T. et al. Extramural depth of tumor invasion at thin-section MR in rectal cancer: associating with prognostic factors and ADC value. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 40 (3), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24398 (2014).

Cho, S. H. et al. Prognostic stratification by extramural depth of tumor invasion of primary rectal cancer based on the Radiological Society of North America proposal. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 202 (6), 1238–1244. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.13.11311 (2014).

Cho, J., Kim, Y. H., Kim, H. Y., Chang, W. & Park, J. H. Extramural venous invasion and depth of extramural invasion on preoperative CT as prognostic imaging biomarkers in patients with locally advanced ascending colon cancer. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 47 (11), 3679–3687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-022-03657-4 (2022).

Saito, G. et al. Relations of Changes in Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels before and after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and after Surgery to Histologic Response and Outcomes in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Oncology 94 (3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485511 (2018).

You, W. et al. Clinical Significances of Positive Postoperative Serum CEA and Post-preoperative CEA Increment in Stage II and III Colorectal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Front. Oncol. 10, 671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00671 (2020).

Cai, Z. et al. Accessing new prognostic significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen in colorectal cancer receiving tumor resection: More than positive and negative. Cancer Biomark. 19 (2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.3233/CBM-160287 (2017).

Halvorsen, T. B. & Seim, E. Association between invasiveness, inflammatory reaction, desmoplasia and survival in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 42 (2), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.42.2.162 (1989).

Sonal, S. et al. Immunological and Clinico-Molecular Features of Tumor Border Configuration in Colorectal Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 236 (1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000000440 (2023).

Aboelnasr, L. S., El-Rebey, H. S., Mohamed, A. & Abdou, A. G. The Prognostic Impact of Tumor Border Configuration, Tumor Budding and Tumor Stroma Ratio in Colorectal Carcinoma. Turk. Patoloji Derg. 39 (1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.5146/tjpath.2022.01579 (2023).

Bramswig, K. H. et al. Soluble carcinoembryonic antigen activates endothelial cells and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 73 (22), 6584–6596. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0123 (2013).

Bajenova, O. et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen promotes colorectal cancer progression by targeting adherens junction complexes. Exp. Cell. Res. 324 (2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr (2014).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BHL conceived and designed the analysis. Data collection was performed by BHL, DHL, JZL and KS. Analysis and interpretation of the data were performed by HBL and KW. BHL, EHJ and XJL critically revised the manuscript focusing on the important intellectual content. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital (Approval No.2022-P2-332-01) and Tai’an City Central Hospital (Approval No. 2024-05-93) waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Consent for publication

Individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, B., Li, D., Li, J. et al. Prediction of Synchronous Serum CEA Expression Status Based on Baseline MRI Features of Primary Rectal Cancer Lesions Pre-treatment: A Retrospective Study. Sci Rep 14, 31469 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83166-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83166-0