Abstract

Knee osteoarthritis offers significant opportunities for prevention and the mitigation of its severity and associated symptoms through lifestyle modifications. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy of an educational intervention based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in promoting preventive behaviors against knee osteoarthritis among women aged over 40 years residing in Fars, Iran. This research utilized a quasi-experimental design. The study population comprised 100 women over the age of 40 who were registered at health centers in Fasa, Iran. Data were collected using a questionnaire based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The intervention was implemented through eight educational sessions specifically designed to promote TPB-informed preventive behaviors against knee osteoarthritis. The findings revealed statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding their scores on attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, and behavior, both before and after the intervention. At 3 months post-intervention, the experimental group demonstrated significant improvements in all measured constructs, while the control group showed no substantial changes. This study demonstrates that implementing structured educational interventions grounded in behavioral theory, specifically the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), can effectively promote preventive behaviors against knee osteoarthritis, thereby potentially reducing its associated morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Degenerative Joint Diseases (DJD) represent one of the most prevalent diseases impacting individuals worldwide1. In 2019, approximately 528 million people worldwide were living with osteoarthritis (OA), representing an increase of 113% since 1990. Approximately 73% of people living with osteoarthritis are older than 55 years, and 60% are female2,3. With a prevalence of 365 million, the knee is the most frequently affected joint, followed by the hip and the hand3,4. Females demonstrate a greater risk for the development of knee OA5, being affected at nearly twice the rate of males6. Women typically have less cartilage and experience greater cartilage volume loss5,7. Both knee laxity and OA symptoms are more severe in females compared to males5,8,9,10. Furthermore, women experience decreased estrogen levels during the postmenopausal period5,11,12. The estimated lifetime risk of knee OA for people with obesity is 24% for females and 16% for males5,13. Yoshimura et al.14 identified a higher prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in women compared to men, suggesting a potential sex disparity in the disease.

Osteoarthritis prevention and treatment can potentially mitigate both its onset and the severity of associated symptoms, which can be achieved through lifestyle modifications, early intervention for genu varum deformity (prior to the manifestation of arthritis), and weight reduction in obese individuals1. Therefore, adopting a healthy and appropriate lifestyle may contribute to lowering the prevalence of osteoarthritis, its complications, and the resultant challenges15. Research by Messier et al. (2021) demonstrated that older adults with knee OA who completed 1.5-year Diet or Diet + Exercise interventions experienced partial weight regain 3.5 years later; however, relative to baseline, they maintained statistically significant changes in weight loss and reductions in knee pain16. A study by Kaddah et al. (2023) revealed that the treatment of proximal tibia vara using high tibial osteotomy (HTO) with a dynamic axial fixator (DAF) in adolescents and young adults proved safe and effective17. Additionally, Preece et al. developed an intervention with five components for knee osteoarthritis (2021): making sense of pain, general relaxation, postural deconstruction, responding differently to pain, and functional muscle retraining, which they termed Cognitive Muscular Therapy. Their preliminary feedback and clinical indications were positive18.

Health experts emphasize lifestyle modification as a cornerstone of treatment, advocating for the adoption of healthy behaviors and the modification of detrimental ones for long-term benefits19. The Theory of Planned Behavior continues to provide a useful framework for research in the social20, health21, and behavioral sciences. The studies reported in these special issues illustrate the ongoing interest in using the TPB to explain and predict behavior in various domains. Furthermore, they demonstrate that the theory is a work in progress, as investigators continue to explore the intricacies of the structural model, such as the moderating effects of perceived behavioral control, and propose additional factors to account for the complexity of human behavior20.

Given the importance of osteoarthritis prevention in vulnerable populations, particularly women, this study aimed to design and implement an educational intervention based on the TPB to promote preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis among women aged over 40 residing in Fasa, Fars province, Iran. The research question addressed in this study was: What is the impact of an educational intervention based on the TPB model on preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis among women aged over 40 residing in Fasa, Fars province, Iran?

Materials and methods

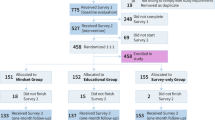

Study design

This research employed a quasi-experimental design that was conducted in 2019. The study sample comprised 100 women aged over 40, all of whom were registered with the Fasa Health Centers in Iran. Two centers were randomly selected from the six available; one served as the control group, and the other was designated as the experimental group. Within each center, 50 subjects were selected using a simple sampling method based on their family file numbers in the computer records (50 per group). The sample size of 100 participants was determined to achieve a significance level of 5% (Type I error) and a power of 95%, while anticipating a 20% mean difference between groups.

The inclusion criteria were: (a) being female and over 40 years old and (b) being literate. The sole exclusion criterion was a pre-existing diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Participation in the study was voluntary, and all participants were assured that their data would remain strictly confidential. Both groups then completed the assigned questionnaires.

After participant selection, the intervention commenced with the experimental group. The intervention program consisted of eight training sessions designed to promote the adoption of preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis, based on the principles of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The behaviors of interest (maintaining a proper diet, achieving proper and sufficient sleep, learning how to sit, walk, stand, and sleep, maintaining weight control, performing exercise according to expert opinion, and understanding the amount and proper execution of these activities) were clearly defined in terms of their target, action, context, and time elements based on Fishbein and Ajzen’s (2010) perspective22. The program employed a multifaceted approach, incorporating lectures, group discussions, role-playing activities, video presentations, and PowerPoint slides. To further enhance engagement, two of the training sessions included workshops led by an orthopedist and physiotherapist, during which participants could be accompanied by a family member. Each participant in the experimental group received an instructional booklet upon completion of the training sessions. Additionally, two follow-up sessions were held at monthly intervals, and weekly text message reminders were sent to participants. To assess the impact of the intervention, both groups completed questionnaires 3 months after the program’s conclusion.

The second section of the questionnaire was designed to assess constructs associated with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), including behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, control beliefs, intention, and behavior. The researchers constructed the TPB questionnaire following Ajzen’s recommendations (1991) to establish the foundation for each construct operationalized within the research tool23,24. The questionnaire’s development was further informed by additional studies25.

Data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire in which participants provided their responses. The questionnaire’s content validity was established through evaluation by health education professionals and rheumatologists. A pilot study confirmed the questionnaire’s reliability using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The alpha values for the constructs under investigation ranged from 0.70 to 0.89, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Participants’ attitudes were evaluated using 12 Likert-scale items (ranging from 1 = “completely disagree” to 5 = “completely agree”). For subjective norms, the questionnaire included 11 items, such as “To prevent knee osteoarthritis, my friends believe I should maintain a proper weight” or “To prevent knee osteoarthritis, my family rarely uses stairs,” measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). Perceived behavioral control was assessed using 10 items, such as “Due to time constraints, it is impossible for me to exercise,” also rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “completely disagree,” 5 = “completely agree”). Participants’ intention to engage in preventive behaviors was measured using 9 items, such as “I intend to exercise regularly to prevent osteoarthritis.” The behavior questionnaire comprised 9 items rated from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“always”). All construct scores were calculated as percentages. Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation), independent t-tests, chi-square tests, and paired t-tests were performed. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The mean age was 51.22 years (SD ± 12.35) for women in the experimental group and 50.39 years (SD ± 12.64) for those in the control group. No significant difference in age was found between the groups (independent t-test, p > 0.05). Similarly, the mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.54 (SD ± 3.34) and 23.01 (SD ± 3.21) for the experimental and control groups, respectively, with no significant difference observed (independent t-test, p > 0.05). Chi-square analysis revealed no significant differences in education level (p = 0.34) or marital status (p = 0.28) between the groups. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Independent t-tests revealed significant differences between the experimental and control groups in pre-intervention scores for attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, and behavior. However, significant improvements in all constructs were observed only in the experimental group three months post-intervention, as evidenced by paired t-tests. The control group showed no significant changes over the same period (see Table 2).

Discussion

Educational interventions serve as a crucial tool in promoting preventive behaviors. Their impact extends beyond individual well-being, demonstrably enhancing quality of life for individuals and reducing the economic burden placed on families and communities affected by chronic disorders. In particular, educating communities about adhering to safety principles and avoiding risky activities can effectively prevent knee osteoarthritis. Drawing upon the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as a theoretical framework, this study aimed to promote preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis among women over 40 who reside in Fasa, Fars province, Iran. The current study demonstrated a significant increase in the experimental group’s mean score for attitudes toward preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis following the educational intervention. The implementation of group discussions and role-playing techniques effectively facilitated the participants’ adoption of preventive behaviors, enabling them to model proper techniques. To further reinforce these positive attitudes, participants received a training booklet upon completion of the program and weekly motivational messages. Mohammadi Zaidi et al. observed a significant positive shift in mean attitude scores among computer users in their experimental group compared to the control group (n = 150)26. Research by Morowatisharifabad et al. (2020) revealed a positive correlation between attitude and self-care behaviors of patients; specifically, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control predicted 8% of the variance in knee OA self-care behavior intention, with attitude emerging as the strongest predictor27. However, Mazlumi et al.25 reported no significant change in participant attitudes following educational intervention. The findings of Jormand et al. (2022) corroborate the current study, demonstrating significant increases in mean attitude scores post-intervention28.

The intervention resulted in a significantly higher mean score for subjective norms within the experimental group compared to the control group. This improvement was potentially facilitated by two key strategies: first, the delivery of educational sessions by an orthopedist and a physiotherapist, who were perceived as credible sources of information and influential figures; and second, a dedicated session involving family members, who also act as influential figures, which targeted abstract subjective norms related to adopting preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis. Family support plays a crucial role in promoting preventive behaviors by creating supportive environments and offering consistent encouragement. Within the culture of Fars province and Fasa, women (mothers, wives, and daughters) play a central and prominent role in the family, and other family members prioritize women’s health over their own. When they perceive women to be at risk, they endeavor to provide additional care and reduce work-related and social pressures. Notably, studies utilizing the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) have demonstrated significant increases in mean subjective norm scores within the intervention group21,28.

According to Supriya and Latika (2023), the lifestyle and family structure prevalent in the Indo-Pak region, where living in joint families is the norm, may be beneficial to patients with rheumatoid diseases compared to other parts of the world where independent living is more common29. However, research by Mazlumi et al.25 and Mohammadi Zaidi et al.26 yielded contrasting results, indicating no significant impact on subjective norms.

The intervention employed training sessions to impart cognitive skills and new behaviors, while group discussions facilitated the exchange of constructive feedback and information. These combined strategies demonstrably enhanced perceived behavioral control within the experimental group. Of note, Robertson et al. observed that ergonomics training in workplaces significantly improved participants’ perceived control and posture30. Similarly, Mohammadi Zaidi et al. reported that the intervention group achieved higher perceived behavioral control scores at 3 and 6 months post-intervention compared to the control group26. Adding further support to these findings, Mazlumi et al. documented higher perceived behavioral control scores in their intervention group compared to the control group25. Martin’s study31 underscored the critical role of perceived behavioral control in facilitating the adoption of proactive behaviors. In the present study, the mean score for women’s intentions regarding preventive measures for knee osteoarthritis demonstrated a significant increase in the intervention group compared to the control group. In accordance with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the experimental group exhibited elevated mean scores for attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control three months after the educational intervention. This synergistic increase ultimately led to the promotion of intentional behavior, thus highlighting the positive impact of the intervention. Similarly, Mohammadi Zaidi et al.26 observed that educational intervention successfully promoted individuals’ intentions to improve their physical condition at both three and six months post-intervention.

Several studies, including those conducted by Akbarian Moghaddam et al.32, Vatanparast et al.33, Alami et al.34, and Rakhshani et al.35, have demonstrated the effectiveness of educational interventions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in increasing participants’ intention to engage in specific behaviors. Consistent with these findings, this study observed that a TPB-based educational intervention successfully promoted preventive behaviors for knee osteoarthritis among women over 40 in the experimental group. By focusing on the key factors influencing behavior change, the intervention employed strategies such as group discussions, active participation, and the clarification of benefits, barriers, and consequences. Additionally, it incorporated skill-building approaches to enhance communication, decision-making, problem-solving, and the acquisition of appropriate behaviors, while providing constructive feedback. Collectively, these elements contributed to the improved adoption of preventive behaviors against knee osteoarthritis within the experimental group. Furthermore, Kalte et al.‘s research lends support to the effectiveness of educational interventions, demonstrating their ability to reduce musculoskeletal risk factors through ergonomics training36.

Numerous studies have highlighted the positive impact of educational programs on health and performance outcomes. Viljanen et al.37 demonstrated a significant reduction in work-related ergonomic problems following an educational program. Similarly, Thomas et al.38 observed a decrease in knee pain among participants aged 45 and over who had undergone an educational intervention. Additionally, Albaladejo39, Coleman40, French41, Kroon42, and Tavafian43 all underscore the positive influence of educational interventions on participant performance. While Erfanian and Zorofi44 observed improvements in pain-related variables in both experimental and control groups after implementing resistance training modifications, Allegrante et al.45 reported performance gains among patients with knee osteoarthritis who participated in a walking training program. Duarte et al.46 examined the effectiveness of applying the Theory of Planned Behavior in predicting physical activity among Portuguese older adults with osteoarthritis. Of particular relevance, Mazlumi et al.25,47 found that a Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)-based educational intervention led to a significant increase in participants’ behavioral scores within the experimental group, thereby demonstrating its potential to drive positive behavioral changes. The researchers acknowledge several limitations encountered during program implementation, including a lack of organizational and financial support, as well as the potential for social desirability bias inherent in self-reported questionnaires used to measure behavior and intention. Future studies should consider incorporating more objective measures, such as physical activity tracking or clinical assessments of knee function. It is recommended that future studies assess participants’ behavior through direct observation and trials, or require them to maintain daily records of their self-care behaviors.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study indicate that implementing educational interventions grounded in theoretical frameworks, particularly the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), aimed at preventing knee osteoarthritis holds promise for reducing its associated morbidity. To maximize effectiveness, such interventions should be specifically tailored through the incorporation of educational methodologies and alternative approaches that facilitate target group acceptance of the desired behavioral changes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Allen, K. D., Thoma, L. M. & Golightly, Y. M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 30 (2), 184–195 (2022).

GBD. : Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (2019).

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. (Key facts), 14 July 2023.

Long, H. et al. Prevalence trends of site-specific osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Arthritis Rheumatol. 74 (7), 1172–1183 (2022).

Messier, S. P. et al. The osteoarthritis prevention study (TOPS) - A randomized controlled trial of diet and exercise to prevent knee osteoarthritis: design and rationale. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open. 6 (1), 100418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2023.100418 (2023).

Vos, T. et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380 (9859), 2163–2196 (2012).

Hanna, F. S. et al. Women have increased rates of cartilage loss and progression of cartilage defects at the knee than men: a gender study of adults without clinical knee osteoarthritis. Menopause N Y N. 16 (4), 666–670 (2009).

McAlindon, T. E., Cooper, C., Kirwan, J. R. & Dieppe, P. A. Knee pain and disability in the community. Br. J. Rheumatol. 31 (3), 189–192 (1992).

Cho, H. J., Chang, C. B., Yoo, J. H., Kim, S. J. & Kim, T. K. Gender differences in the correlation between symptom and radiographic severity in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. 468 (7), 1749–1758 (2010).

Shultz, S. J. et al. ACL research retreat VI: an update on ACL injury risk and prevention. JAthlTrain 47 (5), 591–603 (2012).

Richmond, R. S., Carlson, C. S., Register, T. C., Shanker, G. & Loeser, R. F. Functional estrogen receptors in adult articular cartilage: estrogen replacement therapy increases chondrocyte synthesis of proteoglycans and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2. Arthritis Rheum. 43 (9), 2081–2090 (2000).

Hame, S. L. & Alexander, R. A. Knee osteoarthritis in women. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 6 (2), 182–187 (2013).

Losina, E. et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res. 65 (5), 703–711 (2013).

Yoshimura, N. et al. Risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in Japanese women: heavy weight, previous joint injuries, and occupational activities. J. Rheumatol. 31, 157–162 (2004).

Ng, N., Parkinson, L., Brown, W. J., Moorin, R. & Geeske Peeters, G. Lifestyle behaviour changes associated with osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14, 6242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54810-6 (2024).

Messier, S. P. et al. Changes in body weight and knee pain in adults with knee osteoarthritis 3.5 years after completing diet and exercise interventions. Arthritis Care Res. 74, 607–616 (2022).

Kaddah, A. M., Wesam, G., Alanani, W. G., Hegazi, M. M. & AbdAlFattah, M. T. Management of knee osteoarthritis using percutaneous high tibial osteotomy for correction of genu varum deformity in adolescents and young adults, Egypt. Rheumatologist. 45, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejr.2023.04.003 (2023).

Preece, S. J. et al. A new integrated behavioural intervention for knee osteoarthritis: development and pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 22(1), 526. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04389-0. (2021) (Erratum in: BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022; 23(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04993-0).

Doherty, M., Roddy, E.. Changing life-styles and osteoarthritis what is the evidence? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 20(1), 81–97 (2006).

Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I. & Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 16, 352–356. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107 (2020).

Mohammadkhah, F., Kamyab, A. & Khani Jeihooni, A. Oral cancer preventive behaviors in rural women: application of the theory planned behavior. Front. Oral Health. 5, 1408186. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2024.1408186 (2024).

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach (Psychology, 2010).

Ajzen, I. & Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 1991, 50, 179–211; Ajzen, Handbook of theories of social psychology. 1, 438–459 (2012).

Saffari, M. et al. A theory of planned behavior-based intervention to improve quality of life in patients with knee/hip osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 37 (9), 2505–2515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4120-4 (2018).

MazloomyMahmoodabad, S. S., Bajalan, M., DormohammadiToosi, T., Tarahi, M. J. & Bonyadi, F. The effect of training on adopting behaviors preventing from knee osteoarthritis based on planned behavior theory. Tolooebehdasht 14 (1), 12–23 (2015).

Mohammadi Zeidi, I. & Mohammadi Zeidi, B. The effect of stage–matched educational intervention on reduction in musculoskeletal disorders among computer users. JBUMS 14 (1), 42–49 (2011).

Morowatisharifabad, M. A. et al. Determinants of self-care behaviors in patients with knee osteoarthritis based on the theory of planned behavior in Iran. Indian J. Rheumatol. 15, 201–206. https://doi.org/10.4103/injr.injr_150_19 (2020).

Jormand, H., Mohammadi, N., Khani Jeihooni, A. & Afzali Harsini, P. Self-care behaviors in older adults suffering from knee osteoarthritis: Application of theory of planned behaviour.

Raj, R., Agarwal, S., Gupta, L. Theory of planned behavior—the need of the hour? Indian J. Rheumatol. 17(1), 97–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/injr.injr_252_20 (2022).

Robertson, M. et al. The effects of an office ergonomics training and chair intervention on worker knowledge, behavior and usculoskeletal risk. Appl. Ergon. 40 (1), 124–135 (2009).

Martin, J. J., Oliver, K., McCaughtry, N. The theory of plannedbehavior: predicting physical activity in Mexican American children. J.Sport Exerc. Psychol. 29(2), 225–238 (2007).

Akbarian Moghaddam, Y., Moradi, M., Vahedian Shahroodi, M.,Ghavami, V. Effectiveness of the education based on the theory ofplanned behavior on childbearing intention in single-child women.JHNM. 31(2), 135–145. https://www.hnmj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-1598-en.html (2021).

Vatanparast, Z., Peyman, N., Esmaeili, H. & Gholian Avval, M. Effect of educational program based on the theory of planned behavior on the childbearing intention in one-child women. J. Educ. Community Health. 8 (4), 279–281 (2021).

Alami, A. et al. Effectiveness of an educational intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on fertility intention of single-child women: a field trial study. Intern. Med. Today. 26(3), 212–227. http://imtj.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-3199-en.html (2020).

Rakhshani, T. et al. The effect of education based on the theory of planned behavior to prevent the consumption of fast food in a population of teenagers. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43, 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-024-00640-1 (2024).

Kalte, H. O., Faghih, M. A., Taban, E. & Faghih, A., Yazdani Aval, M. Effectiveness of ergonomic training intervention on risk reduction of musculoskeletal disorders. 3. 1(2), 38–45 (2015).

Viljanen, M. et al. Effectiveness of dynamic muscle training,relaxation training, or ordinary activity for chronic neck pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 327 (7413), 475 (2003).

Thomas, K. S. et al. Home based exercise programme for knee pain and knee osteoarthritis: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 325 (7367), 752 (2002).

Albaladejo, C., Kovacs, F. M., Royuela, A., Del Pino, R. & Zamora, J. The efficacy of a short education program and a short physiotherapy program for treating low back pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Spine 35, 483e96 (2010).

Coleman, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of a self-management education program for osteoarthritis of the knee delivered by health care professionals. Arthritis Res. Ther. ; 14. (2012).

French, S. D. et al. Evaluation of a theory-informed implementation intervention for the management of acute low back pain in general medical practice: the IMPLEMENT cluster randomised trial. PLoS One. 8 (6), e65471 (2013).

Kroon, F., Burg Lvd, Buchbinder, R., Osborne, R., Johnson, R. & Pitt, V. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis (review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1. (2014).

Tavafian, S. S., Jamshidi, A. R. & Montazeri, A. A randomized study of back school in women with chronic low back pain: quality of life at three, six, and twelve months follow-up. Spine 33, 1617e21 (2008).

Erfanian zorofi, F., Mahtab Moazzami, M. & Mohammadi, M. The effect of resistance training on static balance and pain in elderly women with varus knee and osteoarthritis by using elastic band. JPSR 5 (2), 14–24 (2016).

Allegrante, J. P., Kovar, P. A., MacKenzie, C. R., Peterson, M. G. & Gutin, B. A walking education program for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: theory and intervention strategies. Health Educ. Q. 20 (1), 63–81 (1993).

Duarte, N., Hughes, S. L. & Paúl, C. Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Physical Activity among Portuguese Older Adults with Osteoarthritis. Activ. Adapt. Aging. 46 (1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2021.1916717 (2021).

Jeihooni, A. K., Fereidouni, Z., Bahmandoost, M. & Harsini, P. A. The effect of educational intervention on promotion of preventive behavior of knee osteoarthritis in women over 40 based on the theory of planned behavior in sample of Iranian women. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-656824/v1

Acknowledgements

This study was previously published as a preprint in Research Square with this title (51). Formal approval for this study was granted by the Fasa University of Medical Sciences. We express our sincere gratitude to the Research and Technology Department of Fasa University of Medical Sciences for their support. We also extend our heartfelt appreciation to the women who participated in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F., M.B., P.A.H. and A.K.H.J. conceptualized and designed the study, oversaw data collection, conducted data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Z.F. and A.K.H.J. also played a lead role in conceptualizing and designing the study, contributed to data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript thoroughly. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and all authors agree to the revised authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Fasa University of Medical Sciences with the ethical code: IR. FUMS. REC. 1396. 302. Informed consent was secured from all participants, and for students involved, additional parental and/or legal guardian consent was obtained. All methodologies employed strictly adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Maintaining participant privacy was paramount, ensuring data was stored and presented accurately without identifying information. Participants were empowered to withdraw from the interview at any time and were promised access to the final study results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fereidouni, Z., Bahmandoost, M., Harsini, P.A. et al. The effect of an educational intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on the prevention of knee osteoarthritis in women. Sci Rep 14, 31953 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83439-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83439-8