Abstract

The present study explored the determinants influencing students’ intentions towards utilizing digital learning technologies (DLTs). It proposes a holistic view model for students’ utilization of digital learning technologies by integrating social support theory and the “Technology Acceptance Model” (TAM). Data were gathered from 262 students of the University of Ha’il through utilizing a questionnaire. Two steps in SEM were applied for data analysis: CFA was employed to develop the model measurement, and SEM was conducted to analyze the relationships between constructs. The results revealed that “Educational Support” (EDS) significantly affected students’ “behavior intention” (BI) to utilize digital learning technologies through perceived usefulness (PU) (EDS→PU: β = 0.338, p < 0.05). Furthermore, “Emotional support” (EMS) significantly affected behavioral intention through both “perceived ease of use” (PEU) and PU (EMS→PEU: β = 0.635, p < 0.05; EMS→PU: β = 0.310, p < 0.05). Surprisingly, students’ “perceived ease of use” (PEU) did not affect digital learning technologies’ “perceived usefulness” (PU) (PEU→PU: β = 0.195, p > 0.05). The present study contributes to a refined understanding of how educational and emotional support influence students’ receptivity towards and engagement with learning technologies. Thus, institutions and universities should enhance their students’ educational and emotional support to facilitate the successful utilization of digital learning technologies. Furthermore, the study revealed that PU and PEU affected students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. Thus, PU and PEU can enhance the utilization of digital learning technologies. This study provides practical implications that educational institutions and universities could apply to achieve successful usage of these digital learning technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transformation of learning methods in education has received considerable attention recently1,2,3,4,5. Digital learning technologies (DLTs) have received increasing interest in higher education6. DLTs are related to using “information and communication technologies” (ICT) to enhance academic fields7,8,9,10,11. DLTs can build a digital space that includes digital support tools, curricula, and educational services12. DLTs also include other features such as learning by modeling games and animations, live classes, virtual classrooms, and online tutorials13. This allows students to use digital learning materials and sources at any location and time. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, most universities have increasingly utilized DLTs to enhance teaching and student learning14. Educational institutions in several nations, such as the “United States” (US), provide DLTs to approximately 90% of their students15. Additionally, the utilization of DLTs has increased, covering approximately 95 per cent of higher educational institutions in the United Kingdom16. Moreover, the COVID-19 epidemic forced US “higher education institutions” (HEIs) to apply online courses and activate DLTs, resulting in most undergraduate students transferring their learning to online learning. Similar transfers of DLTs have occurred in Asia and Europe. Projections indicate that online learning will comprise between 20 and 25 per cent of all courses within the next decade, while blended learning, encompassing both traditional classroom instruction and distributed learning technologies (DLTs), is expected to constitute the remaining 70 to 80 per cent17. In Saudi Arabia, the “Ministry of Education” (MoE) has formulated an initiative aimed at cultivating student interest and proficiency in the application of DLTs across all educational levels. For instance, the MoE has founded a national center dedicated to e-learning to develop e-learning materials for all academic levels and disciplines. Most universities in Saudi Arabia provide students with DLTs. For instance, the University of Ha’il has transformed some compulsory courses during the first year for their students to be delivered using DLTs, such as virtual classrooms using blackboards, discussion forms, and other technologies. Some of these courses are in the English language, Arabic, and university skills. However, providing students with DLTs did not necessarily lead to their adoption or acceptance of them among students. Therefore, there is a need to assess the factors determining the acceptance of DLTs. Past research has primarily investigated the influence of experience, instructors’ role, Technology acceptance mode (TAM), and students’ views on their acceptance of DLTs18,19. Previous studies have focused on implementing DLTs in schools; however, their current status in higher education remains unclear. Additionally, the practical implementation of DLTs has encountered significant challenges, and their adoption within student communities may not translate to widespread acceptance and active use. Thus, it is critical to assess the variables that could affect the utilization of DLTs among students20,21. To address this research gap, the present study developed a novel theoretical framework model by integrating the tenets of “social support theory” with the TAM. This integrated model aims to comprehensively assess the factors influencing students’ utilization of DLTs. To our knowledge, these two theories have not yet been assessed in the context of the DLTs. Thus, this research adds to the existing body of knowledge in this field by providing a combined theory that properly explains the influential factors affecting students’ utilization of DLTs.

This study examines the determinants that affect students’ behavioural intentions to use DLTs by combining the “Social Support Theory” and the “Technology Acceptance Model” (TAM). This provides several contributions to theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, (1) Integration of models; the integration of “Social Support Theory” into the framework formulated based on TAM helps to expand the picture of the factors that promote the use of DLT. This approach adds extra concepts to the normal foundation of TAM research as different variables such as educational and emotional support. (2) Role of Support; concerning the analysed research hypotheses, it can be stated that emotional support has a positive influence on both PU and PEU of the technology, though educational support affects only PU. Thus, emotional factors are identified as having the most significant impact on the PU and the likelihood of utilising the DLTs among students.

From a practical standpoint, (1) User-Friendly design; specifically, the process means that developers should work on the DLTs that will be useful, easy to use and convenient. This corroborates with the findings that PU and PEU, have a direct influence on the students’ intentions to use these technologies. (2) Enhanced support; the institutions particularly universities should be in a position to offer appropriate education as well as help the student deal with emotional issues. This includes (a) Educational support; assist students in carrying out their operations and provide the effective usage of DLTs. (b) Emotional support; to enhance students’ interaction with DLTs, provide encouragement and respond to their psychological issues. (3) Instructor role; educators should incorporate supportive actions into the teaching approaches, for instance, showing empathy and offering further assistance, a move that will help shift students’ attitudes toward the DLTs.

Literature review

In the study by22, a research model was proposed to investigate the influence of anxiety, self-efficacy, and enjoyment on student satisfaction and acceptance of digital learning. Previous research has had various goals. The issues of security and safety in using digital learning information are important and have been addressed by23,24. Other studies focused on the uptake of digital information. Furthermore, earlier research was carried out to assess the effect of digital storytelling methods on the ability of digital literacy, with a specific focus on developing the adoption method18,25. Moreover, scholars revealed that the digital literacy threshold shifted with the implementing of new digital information technology, implying that students and instructors’ prospectives shifted the difficulties they receive once using new DLTs22,25. Regarding the model used with DLTs, the majority of prior research primarily investigated factors including “perceived ease of use” (PEU), “perceived usefulness” (PU), enjoyment, self-efficacy, and anxiety. Based on the literature review, perceived self-efficacy and support significantly impacted DLTs, whereas parental assistance and self-control were the main barriers for learners. Thus, training program sessions should be provided to student instructors and practitioners in DLTs to address self-efficacy issues18. Some barriers may prevent the adoption of DLTs, such as digital challenges, student attendance, involvement, and connectivity considerations. Therefore, suggestions were made, such as creating content that provides bidirectional communication to enhance interinstitutional collaboration18,24. Although previous literature has used several models focusing on the TAM and extended the TAM to evaluate the adoption and acceptance of digital technologies12,22,26, the current study is different. It integrates the social support theory with the TAM to assess the variables that may influence the adoption and acceptance of DLTs among students. To our knowledge, these model combinations have not yet been assessed in the literature. Thus, this study proposes a theoretical model contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the variables that shape students’ acceptance and utilization of DLTs.

In the context of DLTs, various theories were applied. For instance, the UTAUT which is an extension of TAM, integrates aspects of other models to explain the use of technology comprehensively27. In addition, the “Expectation Confirmation Theory” (ECT) shows further how users’ perceptions in post-adoption affect the sustained use of the technology; extending TAM’s adoption stage28. Further, “innovation diffusion theory” (IDT) explains the process of adopting and diffusion of innovations in the context of the organization29. This study will also examine the integration of TAM with other theories, particularly the “Social Support Theory” (SST). This integration has also been beneficial in the analysis of the effect of social factors on the acceptance of technological commodities in learning institutions30. Thus, incorporating these theories our study, complemented the mentioned shortcomings of previous studies and offered a more enriched theoretical model for explaining the adoption of “Digital Learning Technologies” (DLTs).

This integration addresses limitations of prior research in that it considers the social and contextual factors of using the technology, which are not captured in TAM alone. Thus, with reference to both the SST and the TAM, the present study will try to provide a better perspective on what influences DLT adoption. Such an approach fits well with the novel trends in IT adoption literature that stress the importance of social support and context factors31. Furthermore, expanding the theoretical background will also be useful in future studies, for example, by including other appropriate models like “Expectation Confirmation Theory” (ECT) in the analysis.

Existing research gaps and significance of SST-TAM integration

Previous studies on the perceived use of DLT primarily involve factors like PEU and PU as explained under the TAM. This approach fails to take into account how social and support structures help to determine the extent of technology integration. In particular, there is a significant lack of information on the role of social networks and support systems in changing the perception and acceptance of DLT by users. Most of the existing models take a narrow perspective of categorizing the factors separately as individual or social factors, thus providing a fragmented view of the technology adoption process.

This brings a gap between the two models. In this case, the integration of SST with TAM bridges this gap as it looks at the individual and social factors. SST complements TAM by providing awareness of social networks’ influence on technology acceptance and adds knowledge that social support can either be a positive or negative factor for DLT adoption. This integration enables enhanced and well-coordinated techniques concerning the incorporation of social support as an influential strategy in promoting the acceptance of technology, a more comprehensive and realistic model that depicts the relationship between cognitive and social techniques in influencing DLT.

Theoretical framework

First, the study’s assessment of DLTs benefits from the theoretical framework that encompasses SST and TAM. Second, the integration of SST and the TAM for testing the DLT’s adoption provides theoretical advances in this research area. This integration contributes to new insights in several ways:

1. Maturation of understanding of social dynamics in technology implementation

SST focuses on the influence of the people in an individual’s social circle and their attitudes and behaviours. Regarding the adoption of DLT, SST explains how influences by peers, families, and professional networks may affect people’s decision to accept innovative solutions. TAM in the past has primarily been based on PEU and PU as key adoption constructs of technology. By integrating SST, the model can be expanded to consider how social support affects these perceptions. New insight: When integrated, SST and TAM indicate that social support processes have the potential to cause significant changes to users’ attitudes towards DLT. For example, encouragement by influential nodes in the network could boost the perceived level of usefulness and ease which could in turn increase the rate of acceptance and adoption of DLT.

2. Perception of social factors on technology

Incorporating SST validates that PEU and PU are influenced not only by the technology but also by the social context surrounding the technology. New insight: social support is capable of intervening directly with users’ perception of a given technology. For instance, if a user gets encouragement/ support and suggestions from friends or teachers, such a technology may appear more friendly and helpful to such a user. In other words, technology adoption is much more than a cognitive development exercise but a function of people’s social presence and interaction.

3. Recognition of social support as a modulator of technology adoption factors

TAM factors can be modulated by social support. For example, if there is social support, people can perceive technology as useful and easy to use, even if their initial assessment was otherwise. New insight: This work confirms that social support can function as a facilitator or a shield in technology adoption processes. This implies that there is a way through which attempts to increase the supply of social support to DLT users can help to increase the rates of adoption through positive changes in users’ understanding and predisposed attitudes.

Thus, the integration of SST with TAM explains the concept of DLT adoption by offering more insights into the effects of social support. This approach enriches various theoretical models by integrating individual and social factors in order to provide a more profound understanding of the factors that impact the acceptance and adoption of technology.

TAM

In this study, the authors decided to extend the TAM instead of alternative theoretical models like UTAUT or UTAUT2 since TAM is known to provide fundamental knowledge regarding technology acceptance and has been proven relevant for educational environments. TAM, originally developed by Davis (1986), has a strong theoretical background based on two variables inherent in the technology adoption process: “perceived ease of use” and “perceived usefulness” of the technology in various contexts, including learning settings. TAM is simple to understand and apply, which makes it suitable for studying user acceptance in the context of DLTs.

Although UTAUT and UTAUT2 are better equipped with a number of constructs and the extension of TAM32,33, they may at times overburden the simplistic determinants of the technology acceptance. TAM has been used in a multitude of contexts especially in education as pointed out by Venkatesh and Davis (2000) followed by Venkatesh et al. (2012)34,35,36 and shows how it is capable of measuring important aspects of technology utilization. The emphasis on perceived usefulness and ease of use corresponds to the goal of examining the basic factors that determine DLT adoption.

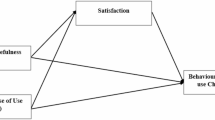

Drawing upon the TAM established by Davis37, this study adopted it as the theoretical foundation, in addition to social support theory. The TAM has two main factors: PEU and PU. Both PEU and PU affect behavioral intentions toward technology. The TAM has been extensively adapted to encompass a broader scope of IT/IS, including those employed within the healthcare domain38, automated vehicles39, e-learning platforms40, and e-business systems41. The research work of Ref42. stated that when considering e-learning as an IT, learners will gain higher intentions to utilise it when they perceive it as a valuable technology that supports and enhances their performance and perceive it as easy to use. Thus, the subsequent hypothesized was formulated:

H1

Students’ PU positively affects their intention toward using DLTs.

H2

Students’ PEU positively affects their intention toward using DLTs.

H3

Students’ PEU positively affects students’ PU.

Social support theory

Social support refers to assistance provided to others and protection from adverse outcomes and unforeseen contingencies43. While direct problem-solving may not be the sole function of support, recent research suggests it plays a crucial role in “critical nudging” and fostering mental well-being44,45. Research on social support has broadened its scope to encompass the online context46,47. Additionally, the e-learning community could produce an effective mutual environment that offers an alternate space for social exchange and social interaction and enhances mental health resilience for members to avoid negative emotions and interactions48.

Educational support (EDS)

EDS refers to tangible assistance; for instance, teachers’ assistance in supporting students in finalizing specific required tasks and providing them with the necessary course materials49. Effective EDS facilitates the interaction with coarse materials; thus, it positively impacts PEU. Additionally, once students have a sense of EDS, for instance, assistance from instructors in solving or explaining problems, they are more likely to participate in and value their courses, enabling them to exercise self-regulation49. Thus, it is expected that EDS could positively affect students’ LP. Therefore, the subsequent hypothesis is proposed:

H4

EDS positively affects PU.

H5

EDS positively affects PEU.

Emotional support (EMS)

Emotionally supportive behavior, hereafter referred to as empathic engagement, encompasses the active provision of compassion, encouragement, positive regard, and expressions of care and affection, fostering a sense of worth and belonging in the recipient49, which lacks both relevance and efficacy in addressing the identified concerns related to the course but is related to uncomfortable experiences and stress that students may have during the use of e-learning. An EMS can minimize the mental efforts required to deal with adverse aspects, resulting in fewer difficulties adopting digital learning. This was explained by cognitive load theory, as less effort is essential and needed to address adverse emotions, which assists in making the mental efforts ready for adopting digital learning50. In the same regard, EMS could decrease students’ efforts to deal with negative emotions and make greater efforts to understand and focus on course materials, thus leading to better effectiveness and efficiency in their learning. Therefore, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H6

EMS positively affects PU.

H7

EMS positively affects PEU.

Proposed research model diagram (Fig. 1).

Methodology

Data collection

This research utilized an online-based questionnaire and the study population was confined to the convenience sampling technique. The online survey was e-mailed to a specific and targeted sample of a student-related online community to be invited to participate. Furthermore, the objective of the study and the link to the online questionnaire was to the respondents through their official e-mails and social media platforms such as the WhatsApp groups, and official social media accounts of the universities. Participation in the study was carried out completely voluntarily. All the respondents were made aware of the anonymity of the data collected and the reasons for the study. A questionnaire was administered to undergraduate students at the University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia. The data collection involved the distribution of 380 questionnaires during the second semester, and 262 respondents were included in further analysis. The population in the College of Education was 817 (532 were enrolled in physical education and sports, and 285 in psychology). Ref51. suggested an acceptable sample size of 800, which should exceed 260. Furthermore, for SEM, which is utilized to analyze the research hypothesis, the minimum sample size should be approximately 20052. Thus, the current received respondents, which is 262, are convenient as a sample size and suitable for further analysis in SEM AMOS.

The study instrument

The survey instrument was divided into two parts. The first part collected background information on the participants, including their demographic characteristics, for example, their major and experiences with utilizing DLTs. These items were self-designed. The second section is concerned with measuring the constructs of the model. Three items measuring PU are adapted from53 to measure the TAM constructs. The three items that measure PEU and three items measuring the BI were adapted from53. To measure the constructs of social support theory, four items measuring EDS and four measuring EMS were adapted from54. A total of 17 were applied to evaluate all factors in the proposed framework. Some word modifications were made to the items to adapt them to the specific context of this investigation. Due to the questionnaire being translated into Arabic, a back-translation was applied. Two bilingual experts (English and Arabic) were asked to translate the questionnaire, which was originally in English to Arabic, to maintain the equivalence of the translation. Each item was assessed using a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger agreement and lower scores indicating stronger disagreement.

Research design and data analysis

A quantitative approach technique was employed for the current research55. This method is the most convenient for achieving the study’s objective: to analyze the relationship between the factors that affect students’ utilization of DLTs. Two approaches were used for data analysis. To analyze the demographic information of the respondents. Two steps were applied in SEM AMOS to analyze the “measurement model” and examine the hypothesized relationships in this study. CFA was utilized to develop the measurement of the model in terms of its construct, convergent, and discriminant validity, and SEM was employed to analyze the relationship and test the study hypotheses in the proposed framework.

Results

Demographic information

A total of 262 male students from the College of Education at the University of Ha’il responded to questionnaires. As shown in Table 1, most students were enrolled in physical education and support (157, 59.9%), while others were enrolled in psychology (105, 40.1%). Regarding their experience using DLTs for learning, most used (207, 79.0%), while the remainder did not (55, 21.0%). An overview of the respondents’ demographic characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

A pooled CFA was run to validate the measurement model and the correlations of the constructs56,57. The construct, convergent, and discriminant validities must be evaluated during CFA before running the SEM57. Thus, construct validity was assessed, and the CFA output is shown in Fig. 2.

Building on Ref.44, construct validity is established when all indices meet the values suggested by the scholars. The findings, illustrated in Table 2, confirm that all indices’ values meet the thresholds previous researchers suggested.

Then, the convergent validity needs to be assessed. According to Ref.57,58, the convergent validity is confirmed when the CR value is > 0.60 and the AVE is > 0.50. Based on the output of CFA, the values confirm that the convergent validity is met as all values of CR are above 0.60, and AVE is above 0.60. Table 3 presents the CR and AVE output. Convergent validity requires to be evaluated before assessing discriminant validity. It is reached once the AVE value is above 0.50 and CR is above 0.6056,57,,57,59. The values were assessed, indicating that convergent validity was achieved in the current research (Table 3).

Finally, to ensure that each construct in the model is discriminant from the other constructs, discriminant validity was checked (see Table 4). According to Ref.57,60,61,62, discriminant validity is reached when all values of AVE in BOLD are greater than the other values in its own columns and rows. Thus, as shown in the output of the discriminant validity, this was confirmed. The table below shows the discriminant analysis.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

Standardized estimate

SEM has two outputs: standardized and unstandardized estimates. The standardized estimate was used to assess the factor loading of items into its constructs, R square, and the strength of the relationships between constructs. The standardized estimate is run, and its output is shown in Fig. 3.

Unstandardized estimate

Calculating an unstandardized estimate is needed to obtain the regression weighting (beta estimate) and critical ratio, which are essential for testing the research hypothesis57,63. The output of an unstandardized estimate is run, and its output is shown in Fig. 4.

Regression weight

The results revealed that PU and PEU significantly affected BI (β = 0.427, p < 0.05; β = 0.185, p < 0.05). Hence, H1 and H2 are confirmed. Furthermore, PEU had an insignificant impact on PU (β = 0.195, p > 0.05). Thus, H3 is rejected. Additionally, EDS significantly affected PU (β = 0.338, p < 0.05). Thus, H4 is confirmed. However, EDS had an insignificant impact on PEU (β = -0.052, p > 0.05). Thus, H5 is rejected. Moreover, EMS significantly affected both PU and PEU (β = 0.310, p < 0.05; β = 0.635, p < 0.05). Thus, H6 and H7 are supported. Table 5 illustrates the statistical analysis for these hypotheses.

Discussion

The present study proposes a theoretical framework combining “social support theory” and the TAM to examine factors affecting students’ intention to utilize DLTs. Then, two steps in SEM AMOS were used to analyze the collected data: CFA for developing the measurement model and SEM for analyzing the relationship between constructs and testing the hypothesis. The results revealed an interesting finding that will be discussed in detail.

Starting with the TAM constructs, the findings revealed that PU and PU affect students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. These results are in line with prior investigations42,64,65,66,67. The results indicated that students were more likely to have positive intentions to utilize DLTs when they perceived them as easy and useful. In other words, when they believe that using DLTs would improve their effective learning and that they are simple to utilize, they would build a positive intention toward using them. Thus, educators and policymakers should focus on providing students with simple and useful DLTs that affect their intentions to utilize them. Furthermore, ICT developers and providers must design vital user-friendly systems to improve their PEU. Additionally, educators may explain to students the effectiveness of using DLTs to improve learning outcomes. This would positively affect their intention to use DLTs and, hence, to use them. Moreover, PEU did not affect PU, which contradicts the results of prior research68,69,70. These findings may explain why when students perceive DLTs as “easy to use” and beneficial, their intention to use them is affected. However, perceiving DLTs as easy to use does not necessarily make them useful. Thus, the PEU did not affect the PU.

The hypothesis that stated that students’ “perceived ease of use” (PEU) has a positive impact on students’ “perceived usefulness” (PU) of “Digital Learning Technologies” was deemed not significant (H3 was not supported). This means that there is no correlation between the “ease of use” of DLTs and “perceived usefulness” by the students. In simpler terms, students’ perception of a certain technology is not enough to conclude that that particular technology enhances learning among students.

The possible reasons for the insignificant effect could be:

-

1.

Other Factors Dominate: There might be other factors, like the quality, the relation to the curriculum content, or the support given by the instructions that might also have an impact on students’ perceived usefulness that is stronger than the perceived ease of use.

-

2.

Technology Maturity: It could be that because the technology is so common that students use it all the time, then ease of use is not a critical factor that students consider in determining the usefulness of the technology.

-

3.

Contextual Factors: Concerning the generalization of the findings, it has been pointed out that the type of technology studied, the age of the students or the type of education may affect the relationship held between PEU and PU.

This finding therefore implies that efforts that seek to make this technology comprehensible are probably not adequate for the promotion of the use of the technology by students. Feedback should also be taken on different factors that makeup perceived usefulness, for example, how the technology supports the learning objectives of a course as well as the practices that are in line with instruction.

The findings also revealed that the emotional support (EMS) affected students’ intention to utilize DLTs through PEU and PU. Our results align with the existing body of research54,71. The results indicate that students’ perceived emotional support from their instructors and peers affected their intentions to utilize DLTs. The emotional support instructors provide can affect students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. The findings also revealed that perceived emotional support affects both PEU and PU, which means that when students perceive emotional support from their instructors, it affects their PEU and PU, resulting in the perception of DLTs as beneficial and “easy to use”. Hence, their intentions to utilize DLTs were affected. Furthermore, for enhancing the adoption of DLTs, there is a need of EMS which is the enthusiastic support shown through teachers embracing and demonstrating care, passion, and positive feedback towards learners. This fosters a sense of belonging and respect for other students in class and this helps create the best learning atmosphere. Though EMS is not primarily focused on course material, the ability of EMS to help learners manage their stress and anxiety towards online classes cannot be dismissed. Hence, EMS can increase students’ ability to attend to and process relevant course information and beliefs while decreasing the demands of negative emotions on cognitive resources50.

Furthermore, the findings showed that the perceived educational support affected students’ intention to utilize DLTs through PU. These findings were consistent with earlier research54,72,73. The findings indicate that when students perceive educational support, such as instrumental support, information support, and support in using DLTs, it affects their intention to use them. Perceived educational support also affects PU. This indicates that when students perceive educational support from their instructor, university administrators, and policymakers, they show the worth and usefulness of DLTs, which affects their perceived usefulness of DLTs, thereby affecting their intention toward utilizing these DLTs. It is also interesting to know that the coefficient of “educational support” (EDS) has no relation to “perceived ease of use” (PEU) when adopting “digital learning technologies” (DLTs) among students (H5 was not supported). This implies that contrary to what would be anticipated if more support would entail students perceiving that the technology is easier to use, this is not what was observed in the present study.

Potential explanations could be: (1) Adequate extant support; in some cases, students might indeed be supported by the appropriate educational aid, somewhere it is possible that extra support is simply not helping the students. It may be that other variables, such as the nature of the technology as being more straightforward than, say, a computer, or the effectiveness of the instructions provided which translate to good instructional design, play a significant role in the question of PEU. (2) Ineffective Support; such support given to the learners may not be adequate and suitable to aid in solving problems arising from the use of the technology. Thus, the support should address the factors that constitute the inherent difficulty with the use of the technology in order to influence PEU. (3) Other factors predominate in PEU; there can be other influences in PEU such as computer literacy, earlier use of this technology (prior experience) or some parameters of the technology’s interface design that can have a much more defining role in PEU than educational support. These factors could possibly overshadow the effects of EDS.

Therefore, this has a connotation of indicating that augmenting educational support may not be the best way of enhancing students’ PEU of DLTs. It is made clear that more studies are required in order to understand which factors affect PEU in a deeper manner as well as to identify the nature of support interventions which can be introduced to enhance students’ performance. Another factor to qualifies in this research is the context in which it has been formulated. The findings could be limited, in terms of setting or time, and/or may not be applicable to other conditions or human groups.

Theoretical implication

This study differs from previous studies in that it expands the existing body of knowledge by providing a holistic theoretical framework that combines social support theory and the TAM to determine the variables that affect students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. Unlike previous studies conducted in the Saudi Arabian context74,75, the current research proposes a theoretical model that combines two models to examine external factors drawn from social support theory to the TAM, namely educational support and emotional support, along with other TAM constructs. To our knowledge, this combination of the two models has not yet been assessed in the context of DLTs. Thus, it will provide a clear explanation of the factors influencing students’ intention to utilize DLTs, which will assist in successfully implementing these DLTs among students. Furthermore, this study applied a second-generation analysis technique using two steps in SEM AMOS, which clearly explains the associations among all the variables in the suggested combined models.

Practical implication

Because both PU and PEU affect students’ intentions to utilize DLTs, developers, and designers should provide a friendly user interface for DLTs to make them easy to use and useful. When students perceive these DLTs as easy and useful, then that would affect their intention toward utilizing them, hence using them. Furthermore, implementing DLTs requires efforts from universities in higher education to not only provide these digital earning technologies but also to re-evaluate them in terms of how easy they are and how useful they are for students’ learning. Moreover, Educational and emotional support affected students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. Thus, instructors and university administrators should consider the importance of educational and emotional support for students when implementing DLTs. This will lead to a positive intention to utilize them among students. The findings also revealed that emotional support affected both PU and PU, whereas educational support only affected PU. Thus, instructors should focus not only on teaching but also on including the required educational and emotional support, for instance, expressing empathy and care, maintaining interaction with students, and enhancing company.

Furthermore, the practical implications of this study are the integration of the results obtained in the current study with existing knowledge from previous research. undefined.

-

“Perceived Usefulness” (PU) and “Perceived Ease of Use” (PEU) affecting students’ intentions: This is in line with previous studies, e.g.,40. It focuses on simplicity and calls attention to the potential of DLTs that should be explained to students.

-

Educational Support affecting PU: This is in line with the findings made by earlier literature49. Again, it emphasizes that instructors and administrators must guide learners on the application of DLTs and demonstrate how helpful the technologies are in learning.

-

Emotional Support affecting PU and PEU: This accords with the prior research work50. It emphasizes the need for instructors to help students get over their uncertainties and concerns about DLTs.

By linking these results with existing knowledge, the authors can also propose practical implications for:

-

Developers and designers: They should improve the interfaces of DLTs to be user-friendly.

-

Universities: They should also be able to supply DLTs and assess the user-friendliness of the DLTs as well as their effectiveness for student learning.

-

Instructors: When implementing DLTs, they should focus on academic support including guidance and emotional support such as empathy.

In sum, the practical contributions build on the current study to enhance extant knowledge of the factors that drive students’ use of DLTs. This can help stakeholders for planning, executing, and facilitating the proper use of DLTs in learning environments.

Limitations and future work

The limitation in the current research highlights key areas for improvement in future investigations. Firstly, the conclusions were restricted to a single university, and that is why they cannot be applicable to other “high education institutions” (HEIs). For future studies, it is recommended more universities should be sampled or the study should cover both public and private universities across different regions of Saudi Arabia. This procedure of sampling will broaden to ensure that observed behaviours and attitudes towards DLTs are consistent across different educational settings.

Further, the research work’s entirely quantitative approach restricts deeper analysis of the student’s engagement with the DLTs. Integrating paradigms could extend the perspectives of quantitative or, potentially, mixed methods into how aspects such as social support contribute to DLT utilization in a more sophisticated way than simply the numbers. Also, this study adopted “Social Support Theory” (SST) in conjunction with the “Technology Acceptance Model” (TAM); nevertheless, the subsequent research may use other theoretical frameworks like “Expectation Confirmation Theory” (ECT). This could reveal further patterns of DLTs’ utilisation and improve the richness of theoretical paradigms within this sphere.

Conclusion

The current study aimed to examine how educational and emotional support affects students’ intention to utilize DLTs. Thus, a combined theoretical model of “social support” theory and the TAM was developed. The theoretically proposed integrated model was tested using a two-step second-generation analysis technique in SEM AMOS: CFA and SEM. In total, 262 students contributed to this study and completed a questionnaire. The results found that the EMS indirectly affected students’ BI to utilize DLTs through its effect on PU and PET. In contrast, educational support affected students’ intention to utilize DLTs through PU. The findings also revealed that the TAM constructs, namely, PU and PEU, affected students’ intentions to utilize DLTs. The current findings provide an interesting view regarding the important role of educational and emotional support, along with the TAM constructs PU and PEU, in shaping students’ intention to utilize DLTs.

Data availability

Data are contained within the article.

References

Almaiah, M. A. et al. Factors affecting the adoption of digital information technologies in higher education: An empirical study. Electronics 11(21), 3572 (2022).

Alkhwaldi, A. F. Investigating the social sustainability of immersive virtual technologies in higher educational institutions: Students’ perceptions toward metaverse technology. Sustainability 16(2), 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020934 (2024).

Alshammari, S. H. & Alshammari, R. A. An integration of expectation confirmation model and information systems success model to explore the factors affecting the continuous intention to utilise virtual classrooms. Sci. Rep. 14, 18491. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69401-8 (2024).

Alshammari, S. H. & Alshammari, M. H. Factors affecting the adoption and use of ChatGPT in higher education. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 20(1), 1–16 (2024).

Khalifeh, A. et al. Influence of students’ self-control and smartphone E-Learning readiness on Smartphone-Cyberloafing. J. Inf. Technol. Educ.: Res. 23, 016 (2024).

Ambalov, I. A. Resistance to online learning technology: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Inf. Dev. 02666669241257197 (2024).

Elkaseh, A., Wong, K. W. & Fung, C. C. A review of the critical success factors of implementing E-learning in higher education. Int. J. Technol. Learn. 22(2) (2015).

Alksasbeh, M., Abuhelaleh, M. & Almaiah, M. Towards a model of quality features for mobile social networks apps in learning environments: An extended information system success model (2019).

Almaiah, M. A., Jalil, M. A. & Man, M. Preliminary study for exploring the major problems and activities of mobile learning system: A case study of Jordan (2016).

Almaiah, M. A. et al. The role of quality measurements in enhancing the usability of mobile learning applications during COVID-19. Electronics 11(13), 1951 (2022).

Al-Adwan, A. S. et al. Unlocking future learning: Exploring higher education students’ intention to adopt meta-education. Heliyon 10(9), e29544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29544 (2024).

Songkram, N. & Chootongchai, S. Adoption model for a hybrid SEM-neural network approach to education as a service. Educ. Inform. Technol. 25(5), 5857–5887 (2022).

Paechter, M., Maier, B. & Macher, D. Students’ expectations of, and experiences in e-learning: Their relation to learning achievements and course satisfaction. Comput. Educ. 54(1), 222–229 (2010).

Sobaih, A. E. E., Hasanein, A. & Elshaer, I. A. Higher education in and after COVID-19: The impact of using social network applications for e-learning on students’ academic performance. Sustainability 14(9), 5195 (2022).

Songkram, N. et al. Students’ adoption towards behavioral intention of digital learning platform. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28(9), 11655–11677 (2023).

McGill, T. J. & Klobas, J. E. A task–technology fit view of learning management system impact. Comput. Educ. 52(2), 496–508 (2009).

Bates, T. Online Enrolments After Covid-19: A Prediction, Part 2–Policy Implications (Online Learning and Distance Education Resources, 2020).

Börnert-Ringleb, M., Casale, G. & Hillenbrand, C. What predicts teachers’ use of digital learning in Germany? Examining the obstacles and conditions of digital learning in special education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36(1), 80–97 (2021).

He, T. et al. Exploring students’ digital informal learning: The roles of digital competence and DTPB factors. Behav. Inf. Technol. 40(13), 1406–1416 (2021).

Al-Gahtani, S. S. Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: A structural equation model. Appl. Comput. Inf. 12(1), 27–50 (2016).

Al-Rahmi, W. M. et al. Social media–based collaborative learning: The effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberstalking and cyberbullying. Interact. Learn. Environ. 30(8), 1434–1447 (2022).

Sayaf, A. M. et al. Information and communications technology used in higher education: An empirical study on digital learning as sustainability. Sustainability 13(13), 7074 (2021).

Wahyuningsih, T., Oganda, F. P. & Anggraeni, M. Design and implementation of digital education resources blockchain-based authentication system. Blockchain Front. Technol. 1(01), 74–86 (2021).

Aydin, E. & Erol, S. The views of Turkish language teachers on distance education and digital literacy during covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 9(1), 60–71 (2021).

Çetin, E. Digital storytelling in teacher education and its effect on the digital literacy of pre-service teachers. Think. Skills Creat. 39, 100760 (2021).

Almaiah, M. A. et al. Determinants influencing the continuous intention to use digital technologies in higher education. Electronics 11(18), 2827 (2022).

Venkatesh, V. et al. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 425–478 (2003).

Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 351–370 (2001).

Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations 551 (Free Press, 2003).

Kong, F. et al. Technology acceptance model of mobile social media among Chinese college students. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 6, 365–369 (2021).

Yakubu, M. N. & Dasuki, S. I. Factors affecting the adoption of e-learning technologies among higher education students in Nigeria: A structural equation modelling approach. Inf. Dev. 35(3), 492–502 (2019).

Alkhwaldi, A. F. & Al-Ajaleen, R. T. Toward a conceptual model for citizens’ adoption of smart mobile government services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan. Inf. Sci. Lett. 11(2), 573–579 (2022).

Dbesan, A. H., Abdulmuhsin, A. A. & Alkhwaldi, A. F. Adopting knowledge-sharing-driven blockchain technology in healthcare: a developing country’s perspective. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-01-2023-0021 (2023).

Venkatesh, V. & Davis, F. D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 46(2), 186–204 (2000).

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L. & Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 36(1), 157–178 (2012).

Liu, G. & Ma, C. Measuring EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT in informal digital learning of English based on the technology acceptance model. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 18(2), 125–138 (2024).

Davis, F. D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1985).

Kamal, S. A., Shafiq, M. & Kakria, P. Investigating acceptance of telemedicine services through an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Technol. Soc. 60, 101212 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transport. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 98, 207–220 (2019).

Sánchez-Prieto, J. C., Olmos-Migueláñez, S. & García-Peñalvo, F. J. Informal tools in formal contexts: Development of a model to assess the acceptance of mobile technologies among teachers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 519–528 (2016).

Taherdoost, H. Development of an adoption model to assess user acceptance of e-service technology: E-service technology acceptance model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 37(2), 173–197 (2018).

Mailizar, M., Burg, D. & Maulina, S. Examining university students’ behavioural intention to use e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended TAM model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26(6), 7057–7077 (2021).

Wortman, C. B. & Dunkel-Schetter, C. Conceptual and methodological issues in the study of social support. In Handbook of Psychology and Health: Stress, Vol. 5 (eds Baum, A. & Singer, J. E.) 63–108 ( Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1987).

Hu, X. et al. Understanding the impact of emotional support on mental health resilience of the community in the social media in Covid-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 308, 360–368 (2022).

Lin, T. C. et al. Exploring the relationship between receiving and offering online social support: A dual social support model. Inf. Manag. 52(3), 371–383 (2015).

Liu, C. & Ma, J. Social support through online social networking sites and addiction among college students: The mediating roles of fear of missing out and problematic smartphone use. Curr. Psychol. 39(6), 1892–1899 (2020).

Yao, Z. et al. Influence of online social support on the public’s belief in overcoming COVID-19. Inf. Process. Manag. 58(4), 102583 (2021).

Marzouki, Y., Aldossari, F. S. & Veltri, G. A. Understanding the buffering effect of social media use on anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Humanit. Social Sci. Commun. 8(1) (2021).

Federici, R. A. & Skaalvik, E. M. Students’ perception of instrumental support and effort in mathematics: The mediating role of subjective task values. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 17, 527–540 (2014).

Porumbescu, G. et al. Translating policy transparency into policy understanding and policy support: Evidence from a survey experiment. Public Adm. 95(4), 990–1008 (2017).

Krejcie, R. V. & Morgan, D. W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30(3), 607–610 (1970).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Guilford, 2015).

Wu, B. & Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 67, 221–232 (2017).

He, S. et al. The influence of educational and emotional support on e-learning acceptance: An integration of social support theory and TAM. Educ. Inf. Technol. 1–21 (2023).

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (Sage, 2017).

Hair, J. F. et al. Multivariate Data Analysis New Jersey (Pearson Education, 2010).

Awang, P. SEM Made Simple: A Gentle Approach to Learning Structural Equation Modeling (MPWS Rich Publication, 2015).

Alshammari, S. H. & Alrashidi, M. E. Factors affecting the intention and use of metaverse: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 20(1), 1–14 (2024).

Alshammari, S. H. & Alshammari, M. H. Modelling the effects of perceived system quality and personal innovativeness on the intention to use metaverse: a structural equation modelling approach. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 10, e2331 (2024).

Alkhwaldi, A. F. & Abdulmuhsin, A. A. Understanding user acceptance of IoT based healthcare in Jordan: Integration of the TTF and TAM. In Digital Economy, Business Analytics, and Big Data Analytics Applications. Studies in Computational Intelligence, Vol. 1010. (eds Yaseen, S. G.) (Springer, Cham, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05258-3_17.

Alkhwaldi, A. F., Alidarous, M. M. & Alharasis, E. E. Antecedents and outcomes of innovative blockchain usage in accounting and auditing profession: an extended UTAUT model. J. Organ. Change Manag. 37(5), 1102–1132. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-03-2023-0070 (2024).

Alharasis, E. E. Evaluating AIS implementation to improve accounting information quality: the prospect in Jordanian family SMEs in the post-Covid-19 age. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-08-2024-0194 (2024).

Alrashidi, O. & Alshammari, S. H. The effects of self-efficacy, teacher support, and positive academic emotions on student engagement in online courses among EFL university students. Educ. Inf. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13139-3 (2024).

Al-Maroof, R. S. et al. Understanding an extension technology acceptance model of Google translation: A multi-cultural study in United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. (3) (2020).

Islam, A. Y. M. A. et al. ICT in higher education: An exploration of practices in Malaysian universities. IEEE Access 7, 16892–16908 (2019).

Sapta, I., Muafi, M. & Setini, N. M. The role of technology, organizational culture, and job satisfaction in improving employee performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 8(1), 495–505 (2021).

Stockless, A. Acceptance of learning management system: The case of secondary school teachers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 23, 1101–1121 (2018).

Devy, N. P. I. R., Wibirama, S. & Santosa, P. I. Evaluating user experience of english learning interface using User Experience Questionnaire and System Usability Scale. In 1st International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences (ICICoS), 2017 (IEEE, 2017).

Granić, A. Experience with usability evaluation of e-learning systems. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 7, 209–221 (2008).

Huang, H. & Liu, G. Evaluating students’ behavioral intention and system usability of augmented reality-aided distance design learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Univ. Access Inf. Soc., 1–15 (2022).

Makmor, N., Alam, S. S. & Aziz, N. A. Social support, trust and purchase intention in social commerce era. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 7(5), 572–581 (2018).

Aristovnik, A. et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability 12(20), 8438 (2020).

Cifuentes-Faura, J. et al. Cross-cultural impacts of COVID-19 on higher education learning and teaching practices in Spain, Oman, Nigeria and Cambodia: A cross-cultural study. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 18(5), 8 (2021).

Alamri, M. M., Almaiah, M. A. & Al-Rahmi, W. M. Social media applications affecting students’ academic performance: A model developed for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 12(16), 6471 (2020).

Alyoussef, I. Y., Alamri, M. M. & Al-Rahmi, W. M. Social media use (SMU) for teaching and learning in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8, 942–946 (2019).

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to all stages of writing and reviewing this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This study has been reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at the University of Hai’l (No. H-2024-009), “and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations”.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alshammari, S.H., Alkhwaldi, A.F. An integrated approach using social support theory and technology acceptance model to investigate the sustainable use of digital learning technologies. Sci Rep 15, 342 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83450-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83450-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Latent obstacles in older adults’ digital health participation: a community-based hybrid cluster analysis with natural language processing

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Cancer patients’ acceptance of virtual reality interventions for self-emotion regulation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Factors influencing AI adoption by Chinese mathematics teachers in STEM education

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Unraveling the dynamics of online learning engagement: a Cambodian perspective

Educational Research for Policy and Practice (2025)

-

Medical students' intentions to use virtual reality for dynamic learning: a TAM-based approach

Education and Information Technologies (2025)