Abstract

Generally, to address the resource management issues in high-speed railway operations, particularly in the context of large-scale networked high-speed train transportation organizations, a phased optimization approach is introduced. This approach divides the problem into two stages: the high-speed train timetabling and the planning of Electric Multiple Unit (EMU) route. The lack of direct integration between these stages has hindered the flexible and efficient utilization of line capacity and EMU resources based on large-scale network, limiting the potential for mutual compensation and coordination among different types of resources across different regions. Furthermore, the coupling between interconnected resources has been overlooked. Compared to the aforementioned phased research areas, this study proposes an integrated optimization of train timetables and EMU routing plans in the context of networking. This study is capable of handling a large number of comprehensive optimization decision variables, which increase exponentially as the number of trains and EMUs considered grows. It thoroughly examines the importance of the linkage and coupling relationships between train timetables and EMUs, providing a new feasible method as the theoretical foundation. Adopting a resource linkage perspective, this paper employs complex system modeling, combined with empirical data from actual high-speed rail cases. This approach can significantly shorten the preparation period for high-speed train timetables and EMU routing plans, accelerating the frequency of updates and upgrades to high-speed rail passenger transportation services. To verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed model and method, a case study was conducted on the EMU circulation plan and draft train timetable for the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway, with the results analyzed accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China has invested a staggering amount of construction funds and accumulated related resources amounting to RMB 6 trillion in its high-speed rail development. By October 2024, it has built 46,000 km of high-speed railways, accounting for over 70% of the world’s total operational high-speed railway mileage, and maintains a fleet of 4,427 standard EMUs (Electric Multiple Units). China boasts an extensive high-speed railway network characterized by its “numerous station points, long railway lines, widespread population coverage, and varying operational conditions across different lines.” The diverse train routes and OD (Origin-Destination) passenger flow demand characteristics vary significantly. The management of the high-speed rail transportation resources is inherently complex. To simplify the resource management problem in high-speed railway operation, the management problem is divided into various stages during the operation plan preparation process. There are two solutions to the allocation of track resources and EMU resources: stage-based and integration. The stage-based optimization method divides the problem into two phases: the high-speed train timetabling and the EMU routing plan. The integration optimization method addresses both aspects simultaneously.

High-speed railway train timetabling involves scheduling train operation times including safety-time intervals and train arrival, departure times, and passage times at stations. Previous research on train timetabling primarily relies on continuous variable and integer 0–1 variable models, with problem-solving techniques such as heuristic algorithms1, genetic algorithms2, simulated annealing algorithms3, hybrid heuristic algorithms4, and commercial mathematical modeling optimization software5. However, the challenge of accurately assessing the solution quality of such models and their limited scalability has diminished the appeal of this modeling method6. Consequently, numerous methods based on spatiotemporal discretization networks have emerged.

The spatiotemporal discretization network-based modeling method has played a key role in advancing networking and enabling precise timetabling of high-speed train schedules7,8. Based on discrete spatial-temporal arc description, train timetabling problems can be depicted using multi-commodity flow models with additional constraints. It can illustrate the logical relationship of track occupation and relax the safety-coupling constraint to achieve the decomposability of the problem. This approach fully facilitates the capabilities of decomposition algorithms to solve large-scale networked train timetabling problems. Column generation9, alternating direction multiplier method10, and bender decomposition11 can be used.

According to recent statistics on the development trend of the transportation industry, EMU resources have emerged as a crucial factor limiting the operation of high-speed passenger and freight trains. In the context of a high-speed railway network, the operation of EMUs utilization faces numerous challenges. The diverse needs of different types of passengers lead to the coexistence of long and short routes, and the existence of multiple operation modes simultaneously complicates the EMU routes planning process. Moreover, while the flexibility of train connections has increased, the difficulty of coordination between different areas has also risen. In China’s high-speed railway system, there are multiple EMU operation modes, including fixed-segment, unfixed-segment, semi-fixed-segment, and cluster modes. The fixed-segment operation mode, as seen in the Beijing-Tianjin intercity railway, is suitable for relatively simple and stable intercity lines. In contrast, the unfixed-segment operation mode is widely applied in high-speed railways with large network coverage and complex lines. By optimizing the EMU routes, the operation of EMUs in different lines and time periods can be rationally arranged, making full use of EMU resources and avoiding waste of transport capacity. Optimization of the routes can also better match the operation of EMUs with line capacity, station facilities, and other resources, thereby improving line utilization and station operation efficiency and achieving the optimal allocation of network resources. The maintenance system and cycle of EMUs affect their operation efficiency. According to China’s railway EMU maintenance regulations, EMUs undergo regular inspections and maintenance to ensure their safe and reliable operation. However, the maintenance resources are limited, with the number of advanced maintenance bases being insufficient and their distribution unbalanced. This results in a relatively tight maintenance capacity, where the demand for maintenance often exceeds the available resources. Therefore, in formulating the EMU operation plan, full consideration must be given to maintenance requirements to ensure that EMUs are maintained on time while avoiding conflicts between maintenance and transportation tasks. The efficient scheduling of maintenance activities and the allocation of maintenance resources are crucial for maintaining the overall operation efficiency of the high-speed railway system.

In general, the multi-commodity flow model with additional constraints can be integrated into the EMU routing plan and decomposed into the shortest path problem while considering resource constraints12,13. The EMU maintenance constraint14,15, which specifies the maximum cumulative running time and mileage of the EMU, must be considered when developing the EMU routing plan16. It can be abstracted into the multi-traveling salesman problem with the challenging constraints and can also be reduced to the vehicle routing problem. Heuristic methods and swarm-intelligence algorithms have become effective approaches for addressing cumulative constraints17,18,19. Zhou et al. established a model by comparing the problem with the problems of aircraft routing and vehicle routing17.

The stage-based optimization method results in the dominance of the train safety constraint structure. First, after the train time schedule is determined, and then the EMU is arranged. This process leads to the restriction of the spatial and temporal layout of the train and the structure of the safety interval coupling relationships. It directly determines the number of EMUs used and the requirements of maintenance resources20. However, it rarely considers adjusting the number of trains and the spatial and temporal layout structure based on the number of EMUs and EMU maintenance resource arrangement21,22. Due to the centralized arrival and departure characteristics of high-speed trains in China, the space available for the EMU turnover and combination of train connections is very limited result in the high demand for EMUs. The high-speed rail transportation system requires a new model that can simultaneously consider the allocation of two types of resources.

The primary approach to integration optimization involves integrating functional modules and achieving indirect resource matching through an “intermediary” method. Yang (2024) comprehensively considers stopping station plans, train schedules, and EMUs22, replacing manual judgment with algorithmic processes and making repeated adjustments until a satisfactory goal is achieved. By establishing an integrated optimization mechanism, the management of high-speed railway track resources and EMU resources can be parallelized facilitating the rapid adaptation of the system to internal and external environmental changes.

The high-speed railway operation plan is a multi-faceted, multi-departmental, and multi-stage interconnected plan that requires coordination among various aspects, including train scheduling and timetabling23, station dispatching24,25, rolling stock and EMU (Electric Multiple Unit) turnover26, track maintenance by railway engineering departments27,28,29, joint scheduling of high-speed railway lines and inspection trains30, synchronized coordination between overnight express trains and track maintenance windows31,32, and train speed control33. Additionally, comprehensive transportation research considers air-rail intermodal transportation for passengers34,35, as well as research on the design of multimodal express transportation networks36. The in-depth research findings on various interconnected coupling relationships in the field of high-speed railway transportation, with the goal of “integrated optimization,” have been continuously and steadily increasing.

In China, the coordination and matching of resources required for train operations rely heavily on manual factors. However, human energy and computational capabilities are insufficient to effectively handle the complex, interconnected, and coupled relationships among multiple resources. In the context of a large-scale, interconnected high-speed railway network, the lack of a top-down design for the transportation organization mode of high-speed trains poses a constraint on the flexible and efficient utilization of line capacity and EMU resources based on a large-scale network model. This, in turn, limits the potential for mutual compensation and coordination among different regions and types of resources, as well as the frequency of iteration and updates of transportation service products.

The phased approach to resource allocation results in a dominant type of safety constraint in the optimization process of train timetables, which restricts the EMU (Electric Multiple Unit) connection relationships. The train timetable is determined first, followed by the allocation and arrangement of EMUs. This sequence leads to restrictions on connection relationships due to the spatial and temporal layout of trains, directly determining the number of EMUs in use and the arrangement of maintenance resources. Conversely, the adjustment of the number of trains and their spatial and temporal layout based on the number of EMUs and maintenance resources is rarely considered. The concentrated arrival and departure characteristics of high-speed trains in China result in very limited space for connection combinations and persistent high demand for the number of EMUs in use. Therefore, a new mode is needed for the high-speed railway transportation system that can simultaneously consider the mutual matching of these two types of resources.

The existing research on the coordination and matching mechanism between route and EMU (Electric Multiple Unit) resources focuses on EMUs passively adapting to the safety coupling relationship structure of train timetables. There is a lack of research from the perspective of improving EMU utilization efficiency to adjust connection coupling relationships and promote refined management of EMU resources. Additionally, there is insufficient research on the interdependent coupling mechanism between changes in connection constraint relationships and the safety constraint relationships. Furthermore, given China’s vast road network structure and connection relationships, as well as complex transportation organization modes and passenger and freight train operation demands, the current human-computer interaction methods employed in the field are insufficient to support substantial improvements in resource matching quality and iterative efficiency of operation plans.

The main contributions of our work are as follows.

-

(1)

Compared with the previously mentioned stage-based research areas, we propose a study on the integrated optimization of train schedules and EMU route plans. From a systemic perspective, we aim to disrupt established management mechanisms, transcend existing high-speed rail resource management theories and practices, and reconstruct the regulatory structure and processes for resource management within the high-speed rail system. We will delve into the coupling effects based on the interoperability of the high-speed rail network and investigate the network-integrated regulatory mechanism for core and critical resources within the system. This research entails handling a vast number of integration optimization decision variables, which increase exponentially as the number of trains and EMUs considered grows. However, only a limited number of studies have explored the establishment of methods for integrating these two resources, and previous studies have been constrained by the limited processing capabilities of available computing resources. Enhancing the coordination of the overall system planning process avoids conflicts between plans at different stages of development. Additionally, it allows for comprehensive consideration of the optimization of both train and EMU operation quality.

-

(2)

To establish a new resource management and regulatory mechanism, it is crucial to understand how to reform the resource regulation process, reduce the transmission, coordination, and control within intermediate links, optimize the hierarchical structure of resource management, and overcome the limitations of the existing departmentalized and phased resource coordination and matching mechanisms that hinder the smooth preparation of train operation plans, the effective sharing and integration of information and transportation resources, and the alignment of objectives across various stages. To improve the existing division of labor and cooperation among departments, the significance of the linkage and coupling relationships between trains and EMUs is fully explored, providing a new and feasible method as the theoretical foundation. This can significantly shorten the preparation time for high-speed rail train schedules and EMU routing plans, accelerating the frequency of updates and upgrades to high-speed rail passenger and freight transportation services. Feedback information can be utilized to promptly ascertain the degree of mutual influence between consecutive stages. Therefore, the optimization method proposed in this paper serve as a crucial supplement to conventional optimization methods.

Method

In this paper, the main goal is to optimize connections, reduce the number of EMUs used, and EMU maintenance tasks based on the provided train line plan and required train travel time window. The factors involved are listed in Table 1.

The process is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the planning of high-speed railway train operations, it is necessary to consider the passenger flow demands and the availability in the train timetabling to achieve integrated optimization of the train timetable and EMU utilization. The high-speed railway train timetable serves as a technical document that indicates the movement of trains within track segments and their arrival, departure, or passing times at stations. The train diagram represents the outcome of competition and interaction among trains for the limited spatial-temporal resources of track lines, aiming to achieve a rational allocation. The problem of scheduling EMUs involves formulating their train connection plans and daily maintenance schedules based on the operational spatial-temporal structure stipulated in the train diagram, in accordance with safety inspection regulations for EMUs, the availability of EMU resources, and management models. This ensures the orderly and efficient circulation and utilization of EMUs.

Model of the EMU routing plan

Tables 2, 3 and 4 clarify the related symbols used in the model.

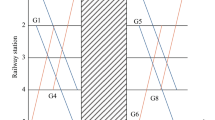

(1) Connection network.

The connection network \(G=({\varvec{N}},{\varvec{A}})\) is a directed graph, where \({\varvec{N}}={\varvec{T}} \cup {\varvec{D}}\) is a collection of nodes and \({\varvec{A}}\) is a collection of directed arcs. T is a given set of train schedules. The conditions for establishing an arc are as follows:

① The destination station of train i is the same as the departure station of train j;

② The arrival time of train i and the departure time of train j meet the connection requirements;

③ The two consecutive trains use the same EMU type;

④ The two connected trains are served by the same operator.

Accordingly, four types of arcs are created as follows: \({\varvec{A}}={{\varvec{A}}_0} \cup {{\varvec{A}}_1} \cup {{\varvec{A}}_2} \cup {{\varvec{A}}_3}\). Here, \({{\varvec{A}}_0}\) is the set of train connection arcs, \(a_{0}^{{ij}} \in {{\varvec{A}}_0}\). When the corresponding trains meet conditions ①, ②, ③ and ④, a train connection arc \(a_{0}^{{ij}}\) is established. An EMU connection of this type generally has a very short travel distance, so the corresponding mileage can be ignored.

\({{\varvec{A}}_1}\) is the deadheading arc set, \(a_{1}^{{ij}} \in {{\varvec{A}}_1}\), for trains that cannot meet condition ① and need a long connection time but can meet conditions ③ and ④. If a connection can be realized by transferring empty cars over a reasonable distance within a reasonable time, then the corresponding deadheading arc \(a_{1}^{{ij}}\) can be established. \(DI{S_{ij}}\) is the distance traveled during the deadheading transfer process, which is a known constant (in this paper, a time of only 30 min is considered, where a certain redundancy time is provided to ensure the feasibility of deadheading transfer).

\({{\varvec{A}}_2}\) is the overnight accommodation arc set, \(a_{2}^{{ij}} \in {{\varvec{A}}_2}\). If a train meets conditions ①, ③ and ④ with respect to the EMU’s required trip to the track at the depot where it will remain overnight after the train tasks of the previous day have been executed, then the accommodation arc \(a_{2}^{{ij}}\) can be established. The destination station of the previous train and the origin station of the subsequent train the next morning may be the same, or trains associated with different stations may be connected. \(DI{S_{ij}}\) is the corresponding travel distance of the accommodation arc.

\({{\varvec{A}}_3}\) is the depot-train arc set, which describes the relationship between the depot nodes and the train nodes. When a depot can provide an EMU of the appropriate type for a particular train task, a corresponding arc is established. When an EMU needs to be maintained after its train tasks are completed, if the depot meets the restrictions on the EMU type, a corresponding depot-train arc can also be established.

(2) Model of the master problem.

Path-formulation variables are defined based on EMU routes with the cost of maintenance tasks as the objective.

EMU circulation plan optimization model:

where \({c_r}\) is the cost of an EMU’s circulation plan, \({c_{r1 }}\) represents the total time for the EMU to turn over in the connection process, \({c_{r2}}\) represents the cost of an EMU maintenance task, and \({w_1}\) and \({w_2}\) are the weight coefficients for the two costs, respectively. Because reducing the EMU purchasing cost provides more benefits than reducing the costs associated with EMU maintenance, \({w_1}\) is much larger than \({w_2}\).

s.t.

Notably, (2) each train must be operated using an EMU, (3) the EMU maintenance limit cannot be exceeded, (4) the capacity for EMU accommodation cannot be exceeded, and (5) the number of used EMU cannot exceed the limitation.

Model of draft train timetabling

The railway company aims to maximize its revenue by reducing costs associated with the number of Electric Multiple Units (EMUs) used and maintenance tasks. The primary goal of the timetabling problem is to minimize train travel durations. The related symbol is explained in Table 5.

Train timetabling model:

The optimization objective is as follows:

In this objective function, \(({t_{SAi}} - {t_{SDi}})\) denotes the train run time, which is to be minimized.

The constraints are as follows.

Train departure time window constraint:

In this paper, the train departure time windows in the model are established to ensure the required train service quality. This quality reflects the standards of passenger transport service, the operational strategy, and the service level of the railway passenger transport enterprise. The departure time of each train must fall within the specified time window.

Shortest train travel time constraint:

This value can be calculated based on the running scale and interval, the shortest stop time and the estimated wait time.

Train departure interval constraint:

Trains with the same origin station need to satisfy this safety constraint.

Station interval time constraints:

Overtaking restriction:

No trains in the set TYX are allowed to overtake each other.

Connection relationship selection constraint:

The alternative connection relationships of each train must be identified to establish a comprehensive turnover relationship.

Connection time constraint:

The difference between the final arrival time of the preceding train, as calculated from its departure time, and the departure time of the subsequent train should be not less than the minimum connection time for the EMU.

Maintenance time window constraints:

The departure time of the train should not be earlier than the end of the railway maintenance time, and the arrival time should not be later than the start of the maintenance time; thus, the high-speed railways in China should adopt rectangular maintenance time windows.

Redundant time range constraint for the travel time:

The relationship between the departure time, the arrival time, and the stop time of a train is as follows:

The departure time of the train plus the travel time is equal to the arrival time at the next station.

The following binary (0–1) decision variable constraint can be established:

The above model is a common mixed-linear-integer programming model that can be solved with CPLEX https://www.ibm.com/docs/zh/icos/12.10.0.

Algorithm

The algorithm process consists of two main modules: the EMU routing planning module and the train timetabling module. The EMU routing planning module primarily focuses on formulating a reasonable train connection plan to meet the train operation demands outlined in the train operation scheme. Simultaneously, it arranges the first-level maintenance tasks and parking of EMUs based on the capacity of the EMU depot, the given EMU operation and maintenance schedule, and the EMU maintenance regulations. The train timetabling module aims to minimize the overall travel time of trains and the deviation from the optimal departure time within the time window. It compiles the train timetable by considering constraints such as passenger service quality, station interval time, EMU resource availability, and comprehensive maintenance windows.

The calculation results can be adjusted based on feedback information related to the following situations: (1) when the demands for train services exceed the transportation capacity, the line plan needs to be reformulated; (2) when the input train connections and the feasibility of the train timetable conflict, it is necessary to return to the first module, adjust the train connection relationships, and recalculate the EMU circulation scheme; and (3) to obtain an improved train timetable, we need to appropriately adjust the departure time windows of the relevant trains and restart the entire coordinated optimization process.

As shown in Fig. 2, first, the EMU circulation planning problem is solved with given departure time windows via column generation to find the optimal linear relaxed train connection relationships.

In the optimization process, the train connections within the EMU circulation plan serve as constraints for the timetabling process. Given these constraints, the timetabling is conducted, and the results are utilized to adjust the parameters for the subsequent iteration. If the outcomes fail to meet the desired level of optimality, this interactive iteration process continues until a satisfactory compromise solution for the objectives of both models is achieved or the allocated computation time is exhausted. In this approach, the departure time window is employed to link the EMU circulation planning problem and the timetabling problem. Initially, the EMU circulation planning problem is tackled using column generation, subject to the specified departure time window, to derive an optimal linear relaxation solution with a dynamic programming algorithm. Subsequently, a macroscopic elementary train timetable is generated through the timetabling process, utilizing the same departure time window. With each iteration, the departure time window is dynamically narrowed based on the computed results for individual trains.

Column generation for EMU circulation

Solution method for the master problem

In this method, the Big M method is used to initialize the model of the restricted master problem, and CPLEX is called to solve the problem. After CPLEX solves the restricted master problem, we obtain not only the optimization result for the restricted master problem but also the optimal solution to the dual problem.

Solution approach for the pricing problem.

Pricing problem model

This model is expressed as follows:

s.t.

In Eq. (21), RC is the reduced cost calculated with the dual variable values (shadow prices of the resources) for each constraint in the restricted master problem model, where \({\pi _i}\)\({\lambda _d}\)\({\rho _d}\)\({\omega _d}\)\(\mu\)are the dual variable value in the Model(1–5) from constraint Eqs. (2), (3), (4), and (5) respectively. Constraint (22) indicates that each train node in the network can be accessed only once per path. Constraint (23) indicates that each EMU can only return to its home-depot for maintenance. Constraint (24) indicates that the mileage accumulated since the last maintenance task should not exceed the mileage specified in the maintenance regulations. Constraint (25) indicates that the time interval from the previous maintenance task to the next maintenance task should not exceed the time specified by the maintenance regulations.

The dynamic programming approach is effective for solving complex problems involving many factors and constraints and offers good algorithmic scalability and solution flexibility. This section details the labeling method. Table 6 explains the parameters used in the approach.

H is the upper limit on the number of labels that can be stored in the set L(i). When the number of generated labels cannot meet the needs of problem optimization, H can be dynamically adjusted as needed. As H increases, the solution time for the problem increases significantly. Each time a new label is produced, if the number of existing labels has reached the upper limit of storage, the new label is compared against the labels in the set L(i). If the newly generated label is better than the existing labels, it is inserted into the set, and the worst label is deleted; otherwise, the new label will be immediately deleted. This comparison process consumes increasingly more time as the storage space increases.

Feasibility Definition. For any i∈NS(r), if \(A{T_i} \leqslant MT\& A{D_i} \leqslant MM\) are satisfied, then route r or the corresponding label is feasible.

Dynamic programming labeling algorithm

Definition

Let \(l_{i}^{1}=(RC_{i}^{1},AD_{i}^{1},AT_{i}^{1},P_{i}^{1})\) and \(l_{i}^{2}=(RC_{i}^{2},AD_{i}^{2},AT_{i}^{2},P_{i}^{2})\) be two labels for node i. If at least one of the inequalities \(RC_{i}^{1} \leqslant RC_{i}^{2}\), \(AD_{i}^{1} \geqslant AD_{i}^{2}\), and \(AT_{i}^{1} \leqslant AT_{i}^{2}\) is satisfied, the label \(l_{i}^{1}\) is considered to be better than \(l_{i}^{2}\).

The list LN is used to store nodes with labels that need to be extended. The function \(Extend(l_{i}^{h},j)\) extends the feasible label lj from the outgoing arcs to node j in accordance with the resource constraints. If the label lj is not feasible, the function will not return a result. The functions START(r) and ARRIVE(r) are used to obtain the starting and end nodes, respectively, of segment r. The details are displayed as following.

Pseudocode for dynamic programming labeling

(1) set \(l_{d}^{1}=(RC_{d}^{1},AD_{d}^{1},AT_{d}^{1},p_{d}^{1})\) with \(RC_{d}^{1}=0\), \(AD_{d}^{1}=0\), \(AT_{d}^{1}=0\), and,\(p_{d}^{1}=(0,...,0)\);

(2) \({\varvec{L}}(d)=l_{d}^{1}\)\(\forall d \in {\varvec{D}}\);

(3) \({\varvec{L}}(i)=\phi\)\(\forall i \in {\varvec{T}}\);

(4) set LN=D;

(5) repeat

(6) select a node i from LN;

(7) parallel.foreach \(l_{i}^{h}=(RC_{i}^{h},AD_{i}^{h},AT_{i}^{h},p_{i}^{h}) \in L(i)\) do

(8) parallel.foreach \(j \in {\varvec{F}}{\varvec{S}}(i)\& \theta _{j}^{h}<1,where\;\theta _{j}^{h} \in P_{i}^{h}\) do

(9) \({l_j} \leftarrow Extend(l_{i}^{h},j)\)

(10) if lj is not null & lj is not dominated by any label in L(j), then

(11) set L(j)=L(j)∪{lj};

(12) remove all labels from \({\varvec{L}}(i)\) that are dominated by lj;

(13) add node j to the list LN if j is not already included in it;

(14) end if

(15) end foreach

(16) end foreach

(17) until LN=ø

(18) return L(d) for all d∈D;

The “parallel.foreach” program is based on pseudocode written in C# in Professional Parallel Programming with C#: Master Parallel Extensions with .NET 4 (Gaston C. Hillar) https://www.microsoft.com/zh-cn/download/details.aspx?id=17718.

Case study

Case situation

The Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway, as shown in Fig. 3, is an important part of the infrastructure in China and is the core of the high-speed railway network. Table 7 is the main capacity parameters in the case.

This is a railway route map of some Chinese cities, showing their railway connections. In the map, red lines indicate main railway lines, blue lines indicate branch lines, and dots indicate stations.

Taking the actual train timetable of the abovementioned Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway as a study case to extract the corresponding line plan, the train departure time windows are determined in accordance with the train departure times in the timetable, with the lower bound on each time window being the original relaxation time minus the given relaxation time. The right endpoint of the time window is the original time plus the relaxation time, and the best time window is the existing departure time. As the reference parameters for adjustment, the detailed information in the train operation plan includes the number of trains, the origin stations, the final arrival stations, the train levels, and so on.

The departure interval between consecutive trains at each station is \(IDD_{s}^{v}=4\hbox{min}\), the arrival interval between consecutive trains at each station is \(IAA_{s}^{v}=5\hbox{min}\), and the minimum turnaround time for each type of EMU at each station is 15 min. The accumulated mileage before first-level maintenance for each of the EMU models is 4000 km, and the corresponding time period is 48 h. The maintenance mileage and time standards can be expanded by 10%, and the time required for a first-level maintenance operation is 4 h. Railway line maintenance starts at \(MS=0:00\) and ends at \(ME=4:00\).

(1) Optimization results analysis

Table 8 shows the cases investigated in our numerical experiments. The originally given departure time is used as a reference.

An extended time window refers to the permissible range for adjusting the arrival and departure times of trains. On the one hand, during the formulation of the EMU routing plan, the time window restricts the adjustable time frame of trains to ensure they are not excessively rescheduled to other time periods. On the other hand, the EMU routing calculated based on a relaxed time window aims to obtain numerous equivalent train connection opportunities under optimal conditions. Considering only strict train connection relationships, i.e., the optimal and unique connection for each train, would impose overly stringent constraints on the compilation of the train operation diagram. Meanwhile, a larger feasible solution space with multiple connections increases the feasibility of generating an effective train operation diagram, thereby ensuring the efficiency of the iterative process. However, if the provided connections are unreasonable, repeated solutions for the routing plan will be required, consuming significant computation time.

EMU routing involves numerous equivalent train connection relationships. When using the same number of EMUs and incorporating as many equivalent connections as possible as input (although this solution is not yet a strictly defined routing plan but a relaxed solution with uncertain connections), the train operation plan optimization model can select the most suitable connections based on those provided by the relaxed solution during the timetabling. The relaxed solution offers a favorable solution space for drawing the train operation diagram. Even if a feasible solution is obtained for the timetable, subsequent trials are needed to reschedule the routing plan based on the timetable, requiring multiple attempts until both the routing plan and the timetable yield feasible and satisfactory optimization results. Therefore, this section mainly proposes a method for solving relaxed EMU routing plans, while strict EMU routing plans are gradually obtained through subsequent adjustments to the train arrival and departure time windows.

Comparisons and analyses of the data in Table 9 show that the overall cost of the EMU circulation plan declines as the time window range expands, while the train travel speed improves. In Cases 1 and 2, the number of EMUs used is 169; in Cases 3, 4, and 5, this number is reduced to 167, and the number of EMU maintenance tasks decreases from the 138 tasks in Case 0 to as few as 118, corresponding to a reduction of 14.5% in the total maintenance task time. The total travel time is also significantly reduced, meaning that passengers can effectively travel at higher speeds, thus improving service. The optimization results for each case in terms of the main important indicators are given in Table 9.

Analysis of the number of EMUs used

Table 9; Fig. 4 shows that the proposed coordinated optimization method can reduce the number of EMUs used. By expanding the time windows, the number of required EMUs is reduced by two. However, in the case of a 25-minute expansion, the number of EMUs does not change. The train timetable can be adjusted and optimized to reduce the number of EMUs used. Figure 5 presents the time-space diagram of the optimized trains for the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway. Figure 5 shows that the main feature of these trains is a long travel distance. During train travel, the running times of most of the trains overlap, resulting in time conflicts between trains. Due to the long travel times of the trains and the small intervals between train departures and arrivals, which are densely distributed in certain periods, there is limited capacity for train adjustment.

In Fig. 5, we plot the train assignments for each EMU. In Fig. 4, we present this data as a Gantt chart, which clearly shows the occupancy times of each EMU. This chart reveals that in a large railway network, trains often travel for long durations and their departure and arrival times cluster within specific periods. Consequently, due to extended travel times and significant train interactions, there is limited flexibility for adjustments. This characteristic increases computational complexity when expanding the departure time window.

Analysis of the number of EMU maintenance tasks

The data in the last column of Table 10 show that with time window expansion and through optimization, the number of EMU maintenance tasks gradually decreases. Table 10 shows the variations in the percentage of maintenance tasks that are performed after different levels of accumulated mileage under different conditions. With time window expansion, the EMU maintenance tasks initially performed after short periods are gradually merged, thus reducing the total number of EMU maintenance tasks. The departure times of some trains that cannot be connected are adjusted so that the same EMUs can accumulate longer operating distances, thereby reducing the number of EMU maintenance tasks.

EMU maintenance after 2000 km to 3000 km accounts for the largest proportion of maintenance because in the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway network, the origin and destination stations of many trains are Beijing South and Shanghai-Hongqiao, between which the mileage is more than 1,300 km. Therefore, it is common to assign EMUs to a circulation plan with a mileage of more than 2,600 km. This will cause the EMUs to need to be maintained every day so that they are ready for use the next day. Otherwise, the next-day EMU usage will violate maintenance regulations.

Analysis of train travel times and speeds

The integration optimization considers the influence of train stops. During adjustment of the train timetable, some train stops will be adjusted may even be canceled; as result, the running speed of the trains is improved. In addition, the actual train timetable includes redundant time as well as the necessary running time; therefore, with optimization, the train travel time is reduced, the running speed is improved, and the train service quality is enhanced.

Conclusion

Because of the current shortage of available EMUs, train operations will be gradually affected as the train timetable and EMU circulation plan are adjusted to accommodate new railway network conditions; consequently, for some lines, the limitations on the available EMU resources must be considered during train operation planning. This study mainly discusses how to improve the efficiency of EMU utilization from the enterprise perspective. We propose a method of optimization based on a given train timetable that is based on a different approach than conventional methods. The proposed EMU circulation planning scheme is mainly designed to optimize the numbers of required EMUs and EMU maintenance tasks considering the train service quality based on a given train schedule and given preferences for passenger travel times.

To verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed model and method, case studies of EMU circulation planning and train timetabling for the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway were investigated, and the results were analyzed. The main innovations presented in this research include the construction of an integration optimization method for the mathematical modeling of the EMU circulation plan and the train timetable to enhance the efficiency of EMU utilization and the train operation quality.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

References

Yixiang Yue, X., Wang, Y. S. & Li, M. Ardeshir Faghri. New heuristic algorithm based on the Lagrangian relaxation for a real-world high-speed railway timetabling problem. Transp. Res. Rec. 2678, 1–15 (2023).

Nitisiri Krisanarach, G., Mitsuo, O. & Hayato A parallel multi-objective genetic algorithm with learning based mutation for railway scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 130, 381–394 (2019).

Zhang Qin, Z., Xiaoning, W. & Li Track allocation optimization in high-speed railway stations from infrastructure management and service perspectives. Meas. Control 51243–51259 (2018).

Gao Yuan, K., Leo, Y., Lixing, G. & Ziyou. Three-stage optimization method for the problem of scheduling additional trains on a high-speed rail corridor. Omega 80, 175–191 (2018).

Xu Guangming, G., Jing, Z., Linhuan, Z. & Fangni, L. Wei. Optimal capacity allocation for high-speed railway express delivery. Comput. Ind. Eng., 185 (2023).

Gestrelius, S., Aronsson, M. & Peterson, A. A MILP-based heuristic for a commercial train timetabling problem. Transp. Res. Proc. 27, 569–576 (2017).

Feng Ziyan, C., Chengxuan, M., Alireza, W., Haizhong, C. & Ximing Uncertain demand based integrated optimisation for train timetabling and coupling on the high-speed rail network. Int. J. Prod. Res. 61 (5), 1532–1555 (2023).

Yue Yixiang, W., Shifeng, Z., Leishan, T. & Lu, S. M. Rapik. Optimizing train stopping patterns and schedules for high-speed passenger rail corridors. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 63, 126–146 (2016).

Wang Jin, Z. & Leishan, Y. Accelerating column generation strategies for high speed railway train timetabling problem form low-carbon and environmentally-friendly. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 20, S408–S415 (2019).

Zhong Mingxuan, Y., Yixiang, Z., Leishan & Zhu Jianping. Parallel optimization method of train scheduling and shunting at complex high-speed railway stations. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. (2023).

Leutwiler Florin, C. & Francesco Set covering heuristics in a Benders decomposition for railway timetabling. Comput. Oper. Res. 159106339 (2023).

Wenjun, L. & Peng, L. EMU route plan optimization by integrating trains from different periods. Sustainability 14 (20), 13457 (2022).

Gao Yuan, S., Marie, Y., Lixing, G. & Ziyou A branch-and-price approach for trip sequence planning of high-speed train units. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 92, 102150 (2020).

Amorosi, L., Dell’Olmo, P. & Giacco, G. L. An integrated model for high-speed rolling-stock planning and maintenance scheduling. Eng. Optim. 2201698 (2023).

Lin Boliang, Z., Yinan, L. & Jian, L. R. Fuzzy programming approach for the electric multiple unit circulation planning problem using simulated annealing. Transp. Res. Rec. 2676 (7), 456–467 (2022).

Qingwei, Z., Lusby Richard, M., Jesper, L., Yongxiang, Z. & Qiyuan, P. Rolling stock scheduling with maintenance requirements at the Chinese high-speed railway. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 126, 24–44 (2019).

Zhou Yu, Z., Leishan, W., Yun, Y. & Zhuo, W. Application of multiple-population genetic algorithm in optimizing the train-set circulation plan problem. Complexity 2017, 1–14 (2017).

Liao Zhengwen, L., Haiying, M., Jianrui, C. & Francesco Railway capacity estimation considering vehicle circulation: Integrated timetable and vehicles scheduling on hybrid time-space networks. Transp. Res. Part C. 124, 102961 (2021).

Habiballahi, M. A. & Tamannaei, M. Hossein Falsafain locomotive assignment problem with consideration of infrastructure and freight train constraints: Mathematical programming model and metaheuristic solution approaches. Comput. Ind. Eng. 172, 108625 (2022).

Zhong, Q. et al. Collaborative optimization of depot location, capacity and rolling stock scheduling considering maintenance requirements. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 7231 (2024).

Hui, J., Bo, L., & Junyuan, H. Research on the framework of intelligent train working diagram compilation technology system based on artificial intelligence. Railway Transp. Econ. 46 (1), 1–9 (2024).

Yang Lin, L., Dewei, W., Hui, G. & Yuan Integrating stop planning, timetabling and rolling stock planning on high-speed railway lines: A multi-objective optimization approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 237(Part b), 121515 (2024).

Yongxiang, Z., Qiyuan, P., Gongyuan, L., Qingwei, Z. & Zhou, X. Integrated line planning and train timetabling through price-based cross-resolution feedback mechanism. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol. 155, 240–277 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. ADMM-based joint rescheduling method for high-speed railway timetabling and platforming in case of uncertain perturbation. Transport. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 152, 104150 (2023).

Li Yawei, H., Baoming, Z. & Peng, Y. Collaborative optimization for train stop planning and train timetabling on high-speed railways based on passenger demand. PLOS ONE. 18 (4), e0284747 (2023).

Habiballahi, M. A., Tamannaei, M. & Falsafain, H. Locomotive assignment problem with consideration of infrastructure and freight train constraints: Mathematical programming model and metaheuristic solution approaches. Comput. Ind. Eng. 172(Part A), 108625 (2022).

Nijland, F., Gkiotsalitis, K. & van Berkum, E. C. Improving railway maintenance schedules by considering hindrance and capacity constraints. Transport. Res. Part C-Emerg. Technol. 126103108 ( 2021).

Hangyu, J. et al. Optimization of train schedule with uncertain maintenance plans in high-speed railways: A stochastic programming approach. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 124, 102999 (2024).

Zhang Qin, L. R., Martin, S., Pan, Z. & Xiaoning A heuristic approach to integrate train timetabling, platforming, and railway network maintenance scheduling decisions. Transp. Res. Part. B Methodol.. 158, 210–238 (2022).

Xu Minhao, S., Bin, W., Xin, L., Jing, H. & Wencheng A two-stage optimization approach for inspection plan formulation of comprehensive inspection train: The China case. Comput. Ind. Eng. 159, 107465 (2021).

Xu Zhengfu, Li, K. & Qinyu, Z. Double-track one-direction operation mode for overnight trains on high-speed railway. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 13 (6), 3527 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Integrated optimization of line planning and train timetabling in railway corridors with passengers’ expected departure time interval. Comput. Ind. Eng. 162, 107680 (2021).

Xuewu, D. et al. Dynamic scheduling, operation control and their integration in high-speed railways: A review of recent research. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (9), 13994–14010 (2022).

Zhang, H., Min, X., & Min, O. A multi-perspective functionality loss assessment of coupled railway and airline systems under extreme events. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 243109831 (2024).

Yuyan, T., Yibo, L., Wang, R., Xiwei, M., Yaxuan, L., Hao, Z., Yu, K. & Yan, W. Improving synchronization in high-speed railway and air intermodality: Integrated train timetable rescheduling and passenger flow forecasting. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23(3), 2651–2667 (2022).

Li Siyu, L., Maoxiang, C., Xinghan, L., Wenqian, S. L. & Weilin, T. Logistics hub location for high-speed rail freight transport with road-rail intermodal transport network. PLOS ONE. 18 (7), e0288333 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Fund of the Ministry of Education (No. 23YJC630094, No. 21YJC630054) and Research Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Science and technology leading talent team project, No. 2022JBQY005); The High-Speed Rail Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U2368212); The Young Scientists Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (72001021); The research plan of China Railway (K2023X047, K2023X031, P2023X029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Li Wenjun, and Tong lu; methodology, Li wenjun and Han peiwen; software, Liwenjun and Hanpeiwen; validation, Lang xiao and Han peiwen; formal analysis, Li wenjun; resources, Tong lu and Li wenjun; writing—original draft preparation, Li wenjun and Han peiwen. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Tong, L., Xiao, L. et al. The integration of optimizing train timetables with EMU route plans. Sci Rep 15, 1705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83501-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83501-5