Abstract

To compare two different secondary IOL fixation techniques, either flanged or hooked, regarding the least required force to dislocate the haptic in human corneoscleral donor tissue (CST). Experimental laboratory investigation. The least required dislocation force (LRDF) of two different fixation techniques, namely the flanged haptics (FH, as described by Yamane) and the harpoon haptic technique (HH, as described by Carlevale) were investigated using 20 three-piece IOLs (KOWA PU6AS) and 20 single-piece IOLs (SOLEKO CARLEVALE) fixated to human scleral tissue. The main outcome, differences in LRDF of the investigated techniques, was measured with a tensiometer. The dislocation force needed to dislocate the flanged haptics was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the flanged 3-piece IOL (0.93 ± 0.43 N) than the specialized, harpoon haptics single-piece IOL (0.45 ± 0.18 N). During externalization, breakage occurred in three harpoon haptics. However, no breakage was observed in either haptics during dislocation. The flanged haptic technique proved to be the stronger form of secondary IOL fixation regarding dislocation force in this in vitro study. The harpoon haptics fixation technique showed significantly less resistance to axial traction and a susceptibility to breakage during externalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prior to the first sutureless intraocular lens (IOL) scleral fixation technique, which was reported by Scharioth in 2007, several surgical methods for secondary intraocular lens (IOL) implantation were employed when there was a lack of capsular support. These methods included anterior chamber IOL fixation, iris fixated IOLs, and transscleral sutured posterior chamber IOLs1,2,3,4,5. While sutured transscleral IOL fixation may be linked to suture erosion and breaking, anterior chamber and iris fixated IOLs may cause corneal endothelial cell loss, glaucoma, and peripheral anterior synechiae4,6,7,8,9,10,11.

Numerous sutureless IOL fixation methods have been described so far, including fixation using glued haptics (Argawal), flanged haptics (Yamane), transscleral tunnels (Scharioth), or bent haptics (Behera/Bolz).1,12–15 Mentioned techniques all have a3-piece IOL in common. In 2020, a special single piece IOL, namely the Carlevale (SOLEKO), has been introduced, which features T-shaped harpoons protruding off the closed haptics to allow self-anchoring in a scleral pocket16.

The requirement for secondary IOL fixation is predicted to increase at a rate commensurate with the anticipated continued rise in the number of cataract procedures performed annually worldwide. Emphasizing this supposition, a recent article could show that IOL dislocation came in third place for problems following IOL exchange, occurring 7.1% of the time, and that the overall number of IOL exchanges grew progressively over time17. The frequency of dislocation within 4 years after secondary IOL implantation is stated as 0.57% in another source18. Dislocation might be due to disinsertion from the haptic through the scleral opening or of the haptic from the optic at their junction. Two important biomechanical parameters are the scleral-haptic dislocation force, followed by the haptic-optic disinsertion force. This was underlined by Ma et al., showing that the force needed for haptic-optic disinsertion for most 3-piece IOLs with PMMA haptics, was higher than the scleral-haptic dislocation force. As a result, the foremost important dislocation parameter is the scleral-haptic dislocation force19.

There are still no long-term studies regarding the durability of the different techniques. In a laboratory study, we could show that the flanged PMMA haptic technique showed most resistance to longitudinal dislocation force compared to the techniques described by Scharioth, Argawal, Behera and Bolz, in vitro20. Spela et al. demonstrated that flanged PVDF haptics even showed a higher least required dislocation force (LRDF) than flanged PMMA haptics21. Moreover, as compared to PMMA haptics, PVDF haptics are less prone to breakage and more resistant to loop memory loss22, thus IOLs consisting of PVDF haptics are recommended for a flanging technique.

The aim of this study is to compare a 3-piece IOL with flanged PVDF haptics and a specialized single piece IOL with T-shaped harpoons, regarding the LRDF from human scleral tissue (CST) in a laboratory setting.

Methods

The requirement for approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) was waived by the local IRB, since remaining human tissues from corneal donor tissues have been used in the experimental set-up. The research was carried out adhering to the Declarations of Helsinki and its later amendments23.

Human corneoscleral tissue

The Medical University of Vienna provided the human CSTs used in the experimental setup. All corneoscleral tissue was not pre-treated with any fixation media, kept in 100 ml culture medium (Tissue C, Alchimia, S.r.l) and used within one month of harvesting. Tissue C consists of balanced saline (EAGLE MEM), 2% bovine serum, sodium bicarbonate, 100 UI/ml penicillin G, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B, and sodium pyruvate, at a pH 7.4 and allows storage of donor tissue for up to one month. The scleral tissue was inspected under the surgical microscope previous to intervention (Zeiss OPMI Lumera 700) for relevant changes and to guarantee uniform thickness, as CSTs without uniform appearance were excluded. In total, 10 CSTs without relevant changes, were included into this study and prepared by one experienced ophthalmologist. Two IOL fixations of each secondary IOL fixation technique were performed on every single CST. Externalization of the haptics were located at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions to ensure uniform conditions. Furthermore, to eliminate any potential influence from the location on the sclera and potential drying of the CST during preparation, the order in which each technique was applied was randomized using list randomization (www.randomizer.org). Throughout the intervention, great care was taken to guarantee a stable graft by irrigating it with culture medium.

Flanged haptic technique

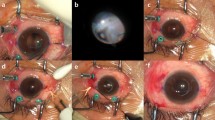

A 3-piece IOL, namely the PU6AS IOL (KOWA, Japan), a hydrophobic, acrylic, biconvex monofocal lens with Polyvinylidenfluorid (PVDF) c-type haptics, with a total diameter of 13.0 mm, an angulation of 5 degrees, and an optic diameter of 6 mm, was used for intrascleral fixation in the flanged haptic group. A 30 gauge (G) thin wall needle with a length of 13 mm (TSK Laboratory Europe, Oisterwijk, Netherlands) was used for the penetration of the sclera and externalization of the haptics. For the creation of the tunnels and flaps, depending on the technique used, the distance was measured with a standardized surgical ruler. An intrascleral tunnel of 2 mm length, parallel to the limbus, was formed with a 30 G needle at a distance of 2 mm to the limbus. The haptic was externalized using the 30 G needle. Then the flange was formed by approaching the tip of a disposable cautery (Accu-Temp, BVI) close to the haptic end, melting 1 mm of the haptic, supported by forceps placed just behind the intended melting length (Fig. 1)13,24. The flange was buried into the sclera by pushing it with forceps.

Harpoon Haptic technique

This technique requires a special IOL, the Carlevale IOL (Soleko, Italy) made out of ultrapurified, copolymer PolyHema, which comes with a total horizontal diameter of 13.2 mm and an optical diameter of 6.5 mm. The harpoons at each end are 1 mm long and the anchor is 2 mm broad to avoid slippage through the formed tunnel.

For the creation of the tunnels, a 3.5 × 3.5 mm partial thickness scleral flap was sculped with a crescent knife up to the limbus. A 25-G needle was used to perforate the deep scleral lamella bed at 1.5 mm distance from the limbus (Fig. 2). Consecutively, a 25G crocodile forceps was used to grasp the specialized IOL at the proximal T-shaped harpoon haptic (HH) and externalize it through the scleral tunnel (Fig. 3). The scleral flaps were sutured with a 10 − 0 Nylon suture. One finding during the performance of the HH technique was that some breakage points in the material became apparent. In two IOLs, at the moment of externalisation with the crocodile forceps, one arm of the harpoon haptics toreoff (Fig. 4). In another case, the bridge of the IOL got separated (Fig. 5). Those three attempts were not included in the analysis.

Tensiometry setup

Applying a horizontal bench setup and a tensiometer (PCE-DFG-N20, PCE Instruments), the dislocation force was measured (Fig. 6)20. Just one haptic end was attached in the CST for each measurement. A straight clamp was used to precisely fixate the IOL at the optic’s centre. To measure the LRDF, the CST was tugged longitudinally in the opposite direction of the tensiometer, using forceps at a distance of 1 mm from the IOL haptic’s attachment point. As a result, the acting force matched the scleral tunnel. The tensiometer was used to monitor the LRDF, which was graphically represented as a constant power curve that ended with forced dislocation of the haptic.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis SPSS Statistics v.27 (IBM) was used. The groups were investigated for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Since the data was normally distributed, it was analyzed using an unpaired t-test. Graphs were generated using R Studio.

Results

The mean dislocation force for the 3-piece IOL PU6AS (KOWA, Japan) was 0.93 ± 0.43 (range 0.23–1.79) Newton (N) and for the specialized Carlevale IOL (Soleko, Italy) 0.45 ± 0.18 N (0.22–0.80). Test of normality showed normally distributed data with a Shapiro-Wilk test. When performing an unpaired t-test between the two groups, a significant difference of 0.38 ± 0.25 N (p < 0.001) became apparent (Fig. 7).

Discussion

There has been no study comparing the LRDF regarding the two mentioned scleral fixation techniques. The results of this laboratory study underline the superiority of the FH technique as described by Yamane compared to the HH fixation technique by Carlevale. A fundamental difference is that no creation of a flap is necessary in the FH technique, furthermore this technique can be applied in 3-piece IOLs made of PMMA and PVDF, depending on location and availability. Erosion of the sclera can be most likely be avoided if performed properly. An advantage of the HH fixation technique is the availability of a toric IOL if needed.

PMMA haptics result in conic shaped flanges when heated and PVDF haptics form mushroom shaped flanges21,24. In a direct comparison, Spela et al. demonstrated that the LRDF was greater for flanged PVDF haptics compared to flanged PMMA haptics. A recent observation of our study group using a study setup similar to this study indicated that the LRDF for flanged PMMA haptics was 1.39 ± 0.39 N, while in this study, the LRDF for flanged PVDF haptics was 0.94 ± 0.39 N20,21. The differences in data between the studies could be attributed to variations in study setup, donor age, tissue storage solution, and storage duration. Thus, in a setup comparable to this study, the LRDF for PMMA haptics was notably higher than the LRDF for the harpoon haptics of the harpoon haptics IOL. We therefore hypothesize that the LRDF for flanged PMMA haptics, similar to flanged PVDF haptics in this study, is significantly higher than that for the harpoon haptics of the Carlevale IOL.

Regarding the material, the harpoon haptics IOL comes with a ultrapurified, copolymer PolyHema. During the measurements, a tendency towards breakage at the harpoon haptics, in two IOLs, and the bridge of the IOL, in one IOL, became apparent. Contrary to the 3-piece IOL, the single-piece IOL is particularly soft and flexible. This advantage during the implantation process might be a point of weakness for fixation of the IOL. Interestingly no haptic breakage occurred in the dislocation process, but in the preceding step, the grasping and externalization. This circumstance could also be influenced by used forceps and should be investigated further. Therefore, particular care is recommended during the externalization process in vivo.

Another study also describes the creation of the scleral tunnel employing a 27 G needle in the FH technique25. This can be contingent upon the surgeon’s inclinations, accessibility in specific countries, or medical facilities. The diameter of the tunnel produced by a 27 G needle is around 400 μm, while a 30 G thin-walled needle produces a diameter of 300 μm. When using the FH technique, heating the haptic by 1 mm produces a flange diameter of about 350 μm. Therefore, in order to produce an ideal flange and prevent lower LRDF, it is advised to heat the haptic by 1.5 to 2 mm from its end while using a 27 G needle24.

One crucial factor might be the amount of time since the sclera has been harvested. Scleras with longer duration since harvesting may alter measurement for the dislocation force. We used all two procedures on each collected sclera to prevent these variances. It should be noted that the sclera in the superior area is often thinner than in the inferior regions of the eye26. A lower LRDF would most likely be the consequence of a thinner sclera. The sequence in which the various procedures were applied to each CST was randomised to mitigate the potential bias resulting from the position on the sclera and the drying process during CST preparation. To counteract drying of the sclera, Tissue-C solution was applied to the sclera with a Q-Tip every minute.

Long-term stabilization variables such as scleral scarring could not be explored because this work was carried out on donor tissue in a laboratory setting. This circumstance may modify the required LRDF in each group to varying degrees. We suggest that it alters the LRDF in both techniques equally, even though the LRDF could be increased by scarring tissue around the anchor. Nevertheless, it should be noted that only the longitudinal force, in respect to the scleral tunnel, was examined during this work, despite our assumption that the measured forces can be transferred to other direction-, expansion-, or acceleration forces in space. Furthermore, it has to be emphasized, that presented results were obtained in vitro, and therefore, it is possible that these cannot be directly extrapolated to in vivo. However, we assume that the acting forces and the LRDF in vivo respond similar to those investigated in vitro.

In conclusion, the FH approach proved to be the more resilient method concerning the LRDF as opposed to the HH technique. With this method, a flange is made that is bigger in diameter than the tunnel the 30 G needle creates; as a result, more force is needed to get past the resistance and dislocate the haptic. The harpoon haptics fixation of the Carlevale IOL proved less secure under axial stress.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (MK) upon reasonable request.

References

Scharioth, G. B. & Pavlidis, M. M. Sutureless intrascleral posterior chamber intraocular lens fixation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg.. 33 (11), 1851–1854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.07.013 (2007).

Anand, R. & Bowman, R. W. Simplified technique for suturing dislocated posterior chamber intraocular lens to the ciliary sulcus. Arch. Ophthalmol. 108 (9), 1205–1206. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1990.01070110021001 (1990).

Friedberg, M. A. & Pilkerton, A. R. A new technique for repositioning and fixating a dislocated intraocular Lens. Arch. Ophthalmol. 110 (3), 413–415. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1992.01080150115039 (1992).

Kokame, G. T., Yamamoto, I. & Mandel, H. Scleral fixation of dislocated posterior chamber intraocular lenses: Temporary haptic externalization through a clear corneal incision. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg.. 30 (5), 1049–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.09.065 (2004).

Thach, A. B. et al. Outcome of sulcus fixation of dislocated posterior chamber intraocular lenses using temporary externalization of the haptics. Ophthalmol. Mar. 107 (3), 480–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00111-6 (2000). discussion 485.

Azar, D. T. & Wiley, W. F. Double-knot transscleral suture fixation technique for displaced intraocular lenses. Am. J. Ophthalmol.. 128 (5), 644–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00244-5 (1999).

Bloom, S. M., Wyszynski, R. E. & Brucker, A. J. Scleral fixation suture for dislocated posterior chamber intraocular lens. Ophthalmic Surg. 21 (12), 851–854 (1990).

Koh, H. J., Kim, C. Y., Lim, S. J. & Kwon, O. W. Scleral fixation technique using 2 corneal tunnels for a dislocated intraocular lens. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 26 (10), 1439–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00477-6 (2000).

Kumar, D. A., Agarwal, A., Packiyalakshmi, S., Jacob, S. & Agarwal, A. Complications and visual outcomes after glued foldable intraocular lens implantation in eyes with inadequate capsules. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg.. 39 (8), 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.03.004 (2013).

Por, Y. M. & Lavin, M. J. Techniques of intraocular lens suspension in the absence of capsular/zonular support. Surv. Ophthalmol.. 50 (5), 429–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.06.010 (2005).

Zeh, W. G. & Price, F. W. Jr. Iris fixation of posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J. Cataract Refract. Surg.. 26 (7), 1028–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00322-9 (2000).

Agarwal, A. et al. Fibrin glue-assisted sutureless posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in eyes with deficient posterior capsules. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 34 (9), 1433–1438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.04.040 (2008).

Yamane, S., Sato, S., Maruyama-Inoue, M. & Kadonosono, K. Flanged intrascleral intraocular lens fixation with double-needle technique. Ophthalmol.. 124 (8), 1136–1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.03.036 (2017).

Behera, U. C. & Thakur, P. S. Scleral Fixation of Intraocular Lens in Aphakic eyes without capsular support: Description of a new technique. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 4689–4696. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S344506 (2021).

Bolz, M., Casazza, M., Reifeltshammer, S. A., Hirnschall, N. & Mariacher, S. Introducing a novel transscleral intraocular lens fixation technique using haptic bending. ESCRS Congress Vienna 2023.

Rossi, T. et al. A novel intraocular lens designed for sutureless scleral fixation: Surgical series. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol.. 259 (1), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04789-3 (2021).

Son, H. S. et al. Visual acuity outcomes and complications after Intraocular Lens Exchange: An IRIS(R) Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) analysis. Ophthalmol. 18 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.10.021 (2023).

Rao, G. N., Kumar, S., Sinha, N., Rath, B. & Pal, A. Outcomes of three-piece rigid scleral fixated intraocular lens implantation in subjects with deficient posterior capsule following complications in manual small incision cataract surgery. Heliyon 9 (9), e20345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20345 (2023).

Ma, K. K., Yuan, A., Sharifi, S. & Pineda, R. A biomechanical study of flanged intrascleral haptic fixation of three-piece intraocular lenses. Am. J. Ophthalmol.. 227, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.02.021 (2021).

Zeilinger, J. et al. Influence of sutureless scleral fixation techniques with 3-piece intraocular lenses on dislocation force. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 10, 264:229–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2024.03.001 (2024).

Stunf Pukl, S. et al. Dislocation force of scleral flange-fixated intraocular lens haptics. BMC Ophthalmol. 5 (1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-024-03369-x (2024).

Izak, A. M. et al. Loop memory of haptic materials in posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J. Cataract Refract. Surg.. 28 (7), 1229–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01326-3 (2002).

World World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama. 27 (20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Kronschlager, M., Blouin, S., Roschger, P., Varsits, R. & Findl, O. Attaining the optimal flange for intrascleral intraocular lens fixation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg.. 44 (11), 1303–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.07.042 (2018).

Kronschläger, M., Blouin, S., Ruiss, M. & Findl, O. Attaining optimal flange size with 5 – 0 and 6 – 0 polypropylene sutures for scleral fixation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg.. 1 (11), 1342–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000001024 (2022).

Dhakal, R., Vupparaboina, K. K. & Verkicharla, P. K. Anterior sclera undergoes thinning with increasing degree of myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.. 9 (4), 6. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.4.6 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to the cornea bank of the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical University of Vienna and especially to the head, Prof. Gerald Schmidinger and the biomedical analyst Bsc. Andrea Binder, for providing the corneoscleral transplants and the seamless cooperation.

Funding

There was no government or non-government support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this manuscript, guarantor is Oliver Findl. JZ (planning, conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing manuscript). AS (analysis and interpretation of data, revising manuscript), NB (planning, acquisition of data, administration, logistics), MK (analysis and interpretation of data, revision of manuscript) OF (guarantor, planning, design, supervision, revision of manuscript).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeilinger, J., Kronschläger, M., Schlatter, A. et al. Comparing dislocation force between a flanged haptics IOL and a harpoon haptics IOL. Sci Rep 14, 32085 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83774-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83774-w