Abstract

Deep learning-based image segmentation has allowed for the fully automated, accurate, and rapid analysis of musculoskeletal (MSK) structures from medical images. However, current approaches were either applied only to 2D cross-sectional images, addressed few structures, or were validated on small datasets, which limit the application in large-scale databases. This study aimed to validate an improved deep learning model for volumetric MSK segmentation of the hip and thigh with uncertainty estimation from clinical computed tomography (CT) images. Databases of CT images from multiple manufacturers/scanners, disease status, and patient positioning were used. The segmentation accuracy, and accuracy in estimating the structures volume and density, i.e., mean HU, were evaluated. An approach for segmentation failure detection based on predictive uncertainty was also investigated. The model has improved all segmentation accuracy and structure volume/density evaluation metrics compared to a shallower baseline model with a smaller training database (N = 20). The predictive uncertainty yielded large areas under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves (AUROCs ≥ .95) in detecting inaccurate and failed segmentations. Furthermore, the study has shown an impact of the disease severity status on the model’s predictive uncertainties when applied to a large-scale database. The high segmentation and muscle volume/density estimation accuracy and the high accuracy in failure detection based on the predictive uncertainty exhibited the model’s reliability for analyzing individual MSK structures in large-scale CT databases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of deep learning (DL)-based image segmentation has allowed for the fully automated, accurate, and rapid analysis of MSK structures from medical images1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. These models assist in extracting the structure’s shape and estimating diagnostic image biomarkers, such as volume and muscle density, for assessing muscle atrophy and fatty degeneration11,12. These biomarkers can be used for the diagnosis of muscle pathologies, such as muscular dystrophy13, cachexia14, and sarcopenia15. The models were tested on the rotator cuff8, chest3, hip and thigh7, and abdominal muscles1,2,4,9,10,16,17. However, multiple issues exist in those studies that limit the reliable application in large-scale databases.

-

Several studies addressed the segmentation of the muscles in only a single or a few two-dimensional (2D) CT slices1,18,19, which do not reflect the three-dimensional (3D) properties of the muscles and depend on the subjective selection of the slices20.

-

The 3D muscle segmentation has also been attempted8,10,21; however, only a few muscles were addressed. A recent study22 addressed the 3D segmentation of 27 hip and thigh muscles in CT images; however, the model was tested on a small database consisting of 12 cases, and the average accuracy was lower than that reported in a previous study targeting similar muscles7.

-

Current muscle segmentation approaches assess the model’s accuracy only in cross-sectional area or volume estimation. However, muscle density, which can be quantified based on the mean Hounsfield units (HU) in the CT image23, has shown higher correlations with muscle strength and functions11,24. This necessitates the accuracy assessment of muscle density estimation, as well.

-

Even though some studies attempted the analysis of large-scale databases21,25, no rigid criteria were applied for segmentation failure detection. In other words, it is not clear how to determine whether the automatic predictions can be safely adopted, possibly corrected with moderate efforts, or better excluded for a reliable downstream analysis.

Our group has developed a segmentation tool, i.e., Bayesian UNet with Monte-Carlo dropout sampling (MCDS), that outputs the model’s uncertainty, a.k.a predictive uncertainty in addition to the target segmentations using multiple predictions from random dropouts of the model weights (i.e. dropout samples) at the inference time7. The model was validated on a database of 20 cases of hip osteoarthritis (hip OA) patients. It has shown high accuracy in segmenting 19 hip and thigh muscles as well as the possibility of predicting the segmentation accuracy in unannotated CT images based on the predictive uncertainty. In the future, we want to leverage this tool to segment large-scale databases of CT images collected from many health centers26, and analyze the impact of the demographic and disease factors in the Japanese population. These databases include large variations from the training data, such as manufacturer/scanner, imaging conditions, and disease variations, which may lead to segmentation failure due to the domain shift problem27,28,29,30. Furthermore, even though the number of dropout samples was found to affect the accuracy of MCDS-based approaches31, the impact of this parameter on the MSK segmentation was not investigated. Fitzpatrick et al. reported the automated volumetric and demographic analysis of the iliopsoas muscle segmented from magnetic resonance (MR) images of 5,000 subjects25. Their database was collected from the UK Biobank database32, which, in contrast to ours, has a unified imaging scanner and protocol that mitigates the domain shift problem. The predictive uncertainty was also addressed in previous studies to predict the segmentation accuracy in unannotated images7,15,33,34,35; however, the analysis was limited to small databases, and no quantitative criteria were applied for the detection of the segmentation failures for the down-stream analysis.

In this study, we report the preparations conducted to employ the model for muscle segmentation in the large-scale database. In particular, a larger fully annotated database consisting of 50 cases of hip OA patients acquired by two CT scanners has been prepared. In addition, the model’s capacity has been increased to account for the enlarged training database. The major contributions of this work are as follows:

-

Investigating the segmentation accuracy and volume/intensity prediction in 22 MSK structures from four databases of CT images acquired from multiple manufacturers/scanners with various disease conditions, and patient positioning, i.e., standing and supine positions.

-

Assessing the accuracy of the predictive uncertainty as a predictor of the segmentation accuracy under various imaging conditions and disease variations and suggesting quantitative criteria for detecting segmentation failures.

-

Showcasing the capability of the predictive uncertainty and suggested criteria in detecting segmentation failures at a large database of > 2,500 volumetric CT images of hip OA patients, and investigating the impact of the disease status on the predictive uncertainty.

Materials and methods

CT images and annotations

In this study, databases of CT images from multiple manufacturers/scanners, disease status, and patient positioning were used. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the databases (DBs) used in this study. DB#1 included pre-operational images from 50 unilateral hip OA patients (mean age: 61.4 ± 13.0 yrs, min: 30 yrs, max: 86 yrs; 44 females, 6 males) acquired by two scanners from different generations by the same manufacturer (HiSpeed ”old” (N=20) and Optima CT660 ”new” (N=30), GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The images were resampled so the slice interval became 1.0 mm throughout the entire volume. The disease severity was assessed using Crowe36 and Kellgren and Lawrence (KL)37 grading, in which higher grades indicate higher disease severity. The affected sides were those with KL,Crowe>1. This database was used for the internal validation of the model accuracy, for investigating the impact of the training and inference settings, and for disease status.

The three databases DB#2-4 were for subjects without hip OA from institutions different from that of DB#1, and were used for external validation of the model accuracy. DB#2 was collected from a public database38, including 18 cases (age anonymized; 13 females, 5 males) with soft tissue sarcoma acquired by a scanner from the same manufacturer as DB#1 but a different model (Discovery ST, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). DB#3 included images for 10 subjects (mean age: 50.1 ±7.6 yrs, min: 41 yrs, max: 64 yrs; 10 males) who were scanned for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer using a scanner from a different manufacturer (Supria, Hitachi Medical, Tokyo, Japan). DB#4 included images of 20 healthy volunteers (mean age: 65.1 ± 6.3 yrs, min: 55 yrs, max: 76). The images were acquired for the volunteers in the supine and standing positions. The supine images were acquired with a 320-row detector CT scanner (Aquilion ONE, Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan), while the standing images were acquired with an upright 320-row detector CT (prototype TSX-401R, Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan)39.

DB#5 included pre-operational images for uni/bilateral hip OA patients collected from the same institution as DB#1. This database was used to showcase the usability of the predictive uncertainty in failure detection and the impact of disease status in a large-scale setting. The original database contained 9,260 CT images, acquired with hip-to-knee and whole lower limb imaging protocols for total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery. Digitally reconstructed radiographs (DRRs) were constructed from each CT volume. The DRR was used to visually confirm the presence of metal implants from hip-to-knee, and truncate the original volume below the knee level if the image covered the whole limb. The process ended up with 2,579 CT volumes (mean age: 61.8 ± 15.2 yrs, min: 13 yrs, max: 98 yrs; 2,062 females, 497 males). The affected and unaffected sides in each CT image were assigned based on an automatic grading model40. Particularly, a cubic region of interest (ROI) centered at the hip center on each side was extracted using a CNN-based landmark detection tool. A DRR was constructed for each side, and was input to a 7-class disease severity classification model with a vision transformer (ViT) architecture41. A pre-trained model with a classification accuracy of .962 was used to predict the disease severity, and the sides with KL,Crowe>1 were considered affected, and unaffected otherwise.

Figure 1 shows an example of the target structures including 19 muscles and three bones, whereas Table 2 lists the structures names, abbreviations used in text, and the visualization colors. A collaborative group consisting of a health science researcher with a medical physics background, computer science researchers, and orthopedic surgeons specializing in musculoskeletal imaging created and validated the ground-truth (GT) labels of all the target structures in DB#1 and the GMED muscle in DBs#2-4. The annotations of the 50 cases in DB#1 passed through multiple annotation and validation cycles. The annotations were first created using a pre-trained model7, and the automated segmentations were corrected using 3D Slicer42.

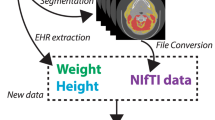

Overall scheme

Figure 2 shows the overall scheme of validating the segmentation model for the automated assessment of bones and muscles in CT images. The CT image was input to the model, where each axial slice was processed to segment the bones and muscles. Each bone and muscle were extracted from the concatenated volume of all slices for qualitative, i.e., muscle density visualization, and quantitative, i.e., volume and mean HU assessments. Besides the bone/muscle labels, the structure-wise predictive uncertainty was computed based on MCDS.7,31 The databases and proposed scheme were used to tackle the following research questions:

-

DB#1: What is the model’s performance (i.e., segmentation and muscle/bone assessment accuracy) under variations the training settings (i.e., number of UNet encoder/decoder layers and number of training cases), and inference settings (number of dropout samples and estimation method of predictive uncertainty)?

-

DB#2–4: How would the model performance change if applied to external databases of CT images from multiple manufacturers/scanners, with various disease conditions and patient positioning (standing and supine positions)?

-

DB#5: Can the predictive uncertainty be used for segmentation failure detection in large-scale unannotated databases?

-

DB#1,5: What is the impact of the disease status on the model performance and predictive uncertainty?

Figure 3 summarizes the research questions in this study with the corresponding databases.

Image segmentation

In this study, a cascaded 2D Bayesian U-Net model, which outputs the predicted structure labels with pixel-wise predictive uncertainty maps, was used7. The baseline model architecture consisted of an encoder and decoder composed of multiple down/upsampling layers (hereinafter called layers for simplicity). Each encoder layer consisted of two basic blocks each consisting of padding-convolution-activation blocks, followed by a dropout block. The decoder layer consisted of an upconvolution block, whose output was concatenated with the corresponding encoder layer’s output, followed by a basic block. The model’s output feature map was input to a softmax layer to obtain the voxel-wise class probabilities. Two modifications were made to the baseline architecture: 1) increasing the depth of the model (i.e., using six encoder/five decoder layers instead of five encoder/four decoder layers), and 2) adding a batch normalization layer43 to the basic convolutional blocks, which stabilizes the training of large neural network models and improves the overall performance33. Similar to7, at the inference time, the mean and the variance of 10 MC dropout samples were used to obtain the output label and voxel-wise uncertainty map, respectively. The structure-wise predictive uncertainty was computed as the average of the voxel-wise uncertainty map within the segmented label.

To investigate the impact of the modified model and larger annotated database, including 50 cases, the performance was compared with the baseline model consisting of five encoder/four decoder layers and validated on 20 or 50 cases. For simplicity, the aforementioned models were termed (5layers,20), (5layers,50), and (6layers,50). The parameters were ∼10 M and ∼44 M for the 5layers and 6layers models, respectively.

Muscle/bone assessment

The labels predicted by the segmentation model were used to assess each structure’s volume and muscle density. The volume was computed as a multiplication of the number of voxels by the size of each voxel in centimeter cubes (cc) normalized by the subject’s height. The muscle density was computed as the mean of the intensity or CT values in HU within the segmented label. Structures on the right and left sides of the patient’s body were assessed separately based on a postprocessing using connected component analysis (CCA). An additional watershed algorithm and CCA were used to separate the right and left sides when connected (e.g., the connection of right and left hemi-pelvises at the pubic symphysis).

A transfer function was used to comprehensively convert the HU values into scalar muscle density to visualize lean muscle and intramuscular fat. HU values less than -30 HU were considered fat, values within the range [−30,30] were considered muscle/fat composite, and values larger than 30 HU were considered lean muscle23. Color and opacity transfer functions were used to visualize the transformed image (see Fig. 2, right).

Evaluation metrics

The segmentation accuracy, and accuracy in estimating the structures volume and density, i.e., mean HU, were evaluated. The segmentation accuracy was evaluated using the Dice coefficient (DC) and average symmetric surface distance (ASD). DC assesses the overlap between the GT and predicted labels. ASD assesses the surface distance, i.e., surface error, to assess the presence of small yet distant false positive structures. The predicted volume and mean HU accuracy were evaluated using the absolute difference between the quantities measured at the GT and predicted labels. The volume error (average volume error [AVE]) was computed as a percentage relative to the GT volume. The intensity error (average intensity error [AIE]) was reported as the average of absolute differences between the mean HUs of the GT and predicted labels.

The accuracy of the predictive uncertainty for detecting inaccurate (correctable with moderate human effort) or failed (correctable with notable efforts) segmentations was investigated. For each structure, a threshold based on the standard deviation of DC was determined to consider the segmentation inaccurate or failed. To make the threshold setting more statistically robust against outliers, the median absolute deviation (MAD) was used. Particularly, a threshold of MedianDC+1.4826∗k*MADDC was used, where k was set as -2 or -3 for inaccurate or failed segmentations, respectively. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves of the predictive uncertainty based on the DC threshold was used to assess the detection accuracy. The AUROCs of the predictive uncertainty from both 5layers,20 and 6layers,50 were computed. Linear regression lines were computed between DC (dependent) and the predictive uncertainty (independent) for each structure and the averages of all structures combined.

Statistical analysis

The concordance correlation coefficient (CCC)44 was used to assess the agreement between the GT and predicted volume and mean HU. The Pearson correlation coefficient (ρ) assessed the linear relationship between the predictive uncertainty and DC. To investigate the statistical significance of the differences between paired measurements, the Shapiro test was first used to assess the normality of the different distributions. Student’s t-test was used when normality was found. Otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. A probability of p = 0.05 was considered significant in all tests. Bonferroni correction was used when multiple comparisons between the models or databases were made.

Implementation details

The proposed approach was developed and validated in Python and Keras45,46. The segmentation models (5layers,20), (5layers,50), and (6layers,50) were trained and validated on DB#1 based on 5-fold cross-validation. For a matched comparison among the models, the remaining 30 out of the 50 cases used in training the (5layers,20) model were used in the inference phase. Models with 5 and 6 layers were retrained on all the images in DB#1 and were used to predict the labels in DBs#2-5. The quantitative validation of DBs#2-4 was limited to the GMED muscle, whereas the average of the predictive uncertainty in all structures was used in DB#5. The predictive uncertainty thresholds used for failure detection in DB#5 were derived based on the linear regression lines computed in DB#1.

The segmentation model training and inference were performed on a Linux-based cluster of servers with graphical processing units (GPUs; Nvidia Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Similar to the previous study7, the (5layers,20) model was trained for 150k iterations with a batch size of 3, whereas the models 5layers,50 and 6layers,50 were trained for 200k iterations due to the increased training data and model capacity. The inference time per volume (approximately 500 CT slices) was approximately 3 minutes.

Results

Segmentation accuracy and predictive uncertainty

The improved model 6layers,50 has shown overall improvements with respect to all evaluation metrics. Figure 4 shows the segmentation accuracy, predictive uncertainty, and volume/mean HU accuracy of the three models. Each point represents the average metric value of all structures in a single subject. The accuracy of the 6layers,50 model was significantly higher than that of the 5layers,20 in terms of all metrics. The average DC of the 6layers,50 model was .945±.015, with an average increase of 1.2% at all structures compared with 5layers,20 (p<.017). An average improvement of approximately 0.4 mm was observed in ASD (p<.017). The improvement by 6layers,50 model was statistically significant in most MSK structures, as shown in Supplementary Figs. A.1 (DC), A.2 (ASD).

Distributions of the segmentation accuracy (a), predictive uncertainty (b), and volume/mean HU accuracy (c) of the bones and muscles (averaged on all structures) by each model applied to DB#1 (N = 50). Horizontal lines in the boxes represent the medians, while blue boxes represent the means. Detailed values are depicted in Supplementary Figs. A.1-A.5. DC: Dice coefficient, ASD: average symmetric surface distance, AVE: average volume error, AIE: average intensity error, n.s.: not significant, *: p < 0.017, Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank sum test with Bonferroni correction

The box plots in Fig. 4(b) show that the uncertainty proportionally decreased with the improved segmentation accuracy in Fig. 4(a) regarding the number of training cases and model depth. Scatter plots of DC versus the predictive uncertainty for each model are depicted in Supplementary Fig. A.6(a). Linear relationships with strong correlations were obtained between the segmentation accuracy and the predictive uncertainty by all the models. A strong correlation of ρ=-.79 was obtained in the 6layers,50 model. This emphasizes the usability of the predictive uncertainty as a predictor of the segmentation accuracy, which supports the findings by the previous studies7,33.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the average DC and average predictive uncertainty of all structures in each patient in DB#1 and the corresponding ROC curve for failure detection. The predictive uncertainty of both models (5layers,20 and 6layers,50) yielded high AUROCs (≥.95) in detecting inaccurate and failed segmentations. Table 3 shows the AUROCs of each structure. The median AUROCs of all structures by 6layers,50 for detecting inaccurate and failed segmentations were .979 and .959, respectively. The OE and OI muscles had the lowest accuracy. Supplementary Fig. A.9 shows the detailed results of each structure. Supplementary Figure A.11 shows scatter plots of the predictive uncertainty by the two models in DB#5. Based on the thresholds computed in DB#1 (Fig. 5), three representative cases were visualized. The improved segmentation by the 6layers,50 model can be observed in the three cases and the scatter plot. The representative case of the failed segmentation exhibits unusual positioning of the hip, possibly due to the patient’s discomfort as a result of the disease.

Relationship between segmentation accuracy/predictive uncertainty and disease stage

Figure 6 shows the distributions of the evaluation metrics and predictive uncertainty at the internal DB#1 (a) and predictive uncertainty in the large-scale database DB#5 (b) in terms of the hip OA disease status (unaffected vs. affected) in each body side. The model 6layers,50 showed statistically significant improvement (p<.01) in all the structure groups in DB#1. The proportional relationship between the accuracy and predictive uncertainty can also be observed in all structure groups, where smaller uncertainty was accompanied by increasing accuracy. The unaffected sides significantly showed higher accuracy in the bones than the affected ones in DB#1. All groups had a similar tendency in DB#5, where the affected sides had higher predictive uncertainty. In addition to the sensitivity to the variations in the positioning, as shown in Fig. A.11, this shows a possible impact of the disease status on the performance of the segmentation model in large-scale databases.

Distributions of the accuracy evaluation metrics and predictive uncertainty of the three MSK structure groups, i.e., thigh (left) and hip (middle) muscles and bones (right), in terms of the disease status of body sides in hip OA patients in internal validation DB#1 (a) and large-scale predictive uncertainty analysis in DB#5) (b). N: number of cases. n.s.: not significant, *: p < 0.004. (Based on Shapiro’s normality test, the hypothesis test was performed using either the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or the Student’s t-test. Bonferroni correction was used for the multiple comparisons.)

Validation on a multi-manufacturer/scanner database

Figure 7 shows the evaluation metrics and predictive uncertainty of GMED muscle segmented at the databases DB#1-4 from multiple manufacturers/scanners and disease variations (see Table. 1). Representative cases (5th (blue filled triangle) and 95th (red filled upside down triangle) quantiles of the predictive uncertainty visualized in Supplementary Figs.A.7 and A.8) are depicted. Statistically significant improvements in the DC, ASD, and AIE were observed in the four databases using the model 6layers,50. The predictive uncertainty was obviously related to the accuracy metrics, where low uncertainty cases mostly had high accuracy metric values and vice versa.

Comparison between segmentation model accuracy (a, c) and predictive uncertainty (b) of the GMED muscle in the multi-manufacturer/scanner databases DB#1(N = 50), DB2(N = 18), DB#3(N = 10) and DB#4(N = 20). DC: Dice coefficient, ASD: Average symmetric surface distance, AVE: Average volume error, AIE: Average intensity error, su: supine, st: standing, n.s.: not significant, *: p < 0.01. (Based on Shapiro’s normality test, the hypothesis tests were performed using either the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or the Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction). The triangles indicate the cases corresponding to the 5th (blue filled triangle) and 95th (red filled upside down triangle) quantiles of the predictive uncertainty visualized in A.7 and A.8.

Table 4 summarizes the means and SDs of the evaluation metrics in the four databases. Using the 6layers,50 model, the segmentation accuracy at a predictive uncertainty of 5 × 10−4 was > 0.90 (DC) and approximately less than 2.00 mm (ASD) in all the databases. Notably, a sub-HU accuracy was obtained in predicting the mean HU in the four databases. Overall improvements were observed in all the muscles by the 6layers,50 model (see Supplementary Fig. A.7). At the GMED muscle, the 5layers,20 model failed to capture the boundaries with the GMAX muscle, which reduced its segmentation accuracy, whereas the errors were less in the 6layers,50 model results. The PSOAS muscle’s lower part was undersegmented in multiple instances by the 5layers,20 model. Noteworthy, only a slight degradation in accuracy was observed at standing compared with the supine positioning in DB#4.

Table 5 summarizes the predictive uncertainty and its correlations with the segmentation accuracy (DC) of the GMED muscle in the four databases. With the four databases combined, both models yielded strong correlations, where the average PCCs for the 5layers,20 and 6layers,50 models were -.85 and -.60, respectively. Table 6 shows the AUROCs of failure detection at the four databases. The median AUROCs by the 6layers,50 were .963 and .995 for inaccurate (-2σ) and failed (-3σ) segmentation detection, respectively.

Muscle/bone assessment

Table 7 compares the volume and mean HU prediction applied to the GT and auto segmentations in DB#1 obtained from the 6layers,50 model. The measurements of the unaffected and affected hip OA sides were reported separately. Most structures exhibited substantial agreement between the GT and auto measurements on both sides (ρ ≥ .95). The PI muscle showed weak agreement in the volume and HU measurements, whereas the TFL muscle showed weak agreement only in mean HU. In both the volume and mean HU predictions, the unaffected side has shown a slightly larger MAE than the affected side. MAE of the predicted volumes at the bones and muscles for the affected and unaffected sides was 1.77±1.06 cc/m2 and 1.89±1.17 cc/m2, respectively. The MAE of the mean HU for the affected and unaffected sides was 1.46±0.95 HU and 1.38±0.89 HU, respectively. Notably, a sub-HU MAE was obtained at the GMAX, GMED, AD, BF, RF, SM, VLVI, VM muscles on the affected and unaffected sides.

Figure 8 shows representative case (median DC) segmentations with muscle histograms and 3D volume rendering of muscle density of the GMAX and GMED muscles. High reproducibility of the GT-based histograms and muscle density visualizations could be observed. In particular, the auto segmentations could comprehensively reproduce lean muscle (red) and fat (yellow) portions.

Ground-truth (GT) and predicted (Auto) segmentations of the unaffected (Un.) and affected (Aff.) sides of a representative hip OA case (median DC in Fig. 4) with diagnostic biomarkers, histograms, and muscle density visualizations of the gluteus maximus (GMAX) and gluteus medius (GMED) muscles.

Impact of the training and inference settings

Number of training images

Table 8 shows the impact of the number of training images on the segmentation accuracy (DC, ASD) of the 6layers model applied to DB#1. The highest accuracy was obtained when 40 cases were used. However, no statistically significant differences were observed in comparison to 30 cases. Compared with cases fewer than 30 cases, statistically significant differences were observed. In addition, strong correlations between DC and the predictive uncertainty were obtained in all numbers of training cases (see Supplementary Fig.A.6,b). This emphasizes the generalizability of the predictive uncertainty as a predictor of the segmentation accuracy regardless of the number of training images.

Number of dropout samples.

Table 9 shows the impact of the number of training samples on the segmentation accuracy by the 6layers model applied to DB#1. No improvement was observed by increasing the samples to larger than 10 samples. This indicates that 10 samples are sufficient to obtain a stable performance by the model.

Estimation method of the predictive uncertainty.

Table 10 shows the correlation between the uncertainty, estimated using entropy and MCDS-based variance, and the segmentation accuracy (DC). Both uncertainties were estimated using the 6layers model applied to DB#1. The entropy was computed from the probability maps of a single sample (deterministic setting) following the previous studies15,33 whereas the MCDS was computed from the variance of 10 dropout samples. The entropy produces stronger correlations with the segmentation accuracy (mean: -.71 vs. -.69); however, the usage of a single sample led to a decreased segmentation accuracy (DC: .941±.014 vs. .947±.013; as shown in Table 9).

Discussion

This study validated a DL model for the segmentation of MSK structures with uncertainty estimation in clinical CT images. The novelty of this work is that it showed the usability of the predictive uncertainty for predicting the MSK segmentation accuracy and detecting segmentation failures in databases of CT images from multi-manufacturers/scanners and with disease and positioning variations, such as supine and standing, and with different scales, including a large-database with 2,579 CTs. This showed the possibility of using the predictive uncertainty as a tool for detecting the failed segmentation in unannotated CT images. The study also exhibited the potential of the 6layers,50 model in producing accurate segmentations for assessing the muscle/bone volume and mean intensity, with DC > 0.90 in almost all the muscles and > 0.95 in the bones (see Supplementary Fig. A.1). The validation on the external databases has shown high generalizability of the model’s performance, where a DC > 0.95 and an AIE < 1 HU were obtained in evaluating the GMED segmentations, and the predictive uncertainty could detect the cases with segmentation failures.

Systematic improvements were observed using the 6layers,50 model at all the structure groups, regardless of the disease status. However, the PI muscle showed the smallest DC of 0.845 ± 0.091, with the largest ASD, AIE, and AVE (see Supplementary Figs. A.1, A.2, A.4, A.5). The degraded accuracy could be interpreted by the location of this muscle among various bony, abdominal, and vascular structures, making it challenging for automated segmentation. 3D segmentation models47 might improve the segmentation accuracy of this muscle as they better involve the volumetric relationships with the surrounding structures.

The predictive uncertainty was investigated in several studies to predict the segmentation accuracy in medical images.7,15,33,34,35. Nowak et al. investigated the predictive uncertainty (entropy) in segmenting skeletal muscles in lumbar-level CT slices from dual centers with CT scanners from multiple manufacturers. Their study showed the applicability of the predictive uncertainty on the data from both centers; however, it was only applied to 2D CT slices, with the muscles combined into a single label. Mehtrash et al. investigated the predictive uncertainty (entropy) based on ensemble models. The method was validated on multiple structures at MRIs, and strong correlations between the predictive uncertainty and segmentation accuracy were reported. However, both studies did not address the segmentation of individual muscles or bones and did not investigate the impact of practically important factors, such as disease condition or numbers of training data on the segmentation accuracy15,33. In our experiments, we attempted to use the entropy of single samples and observed slightly improved correlations with the segmentation accuracy. However, the segmentation accuracy has decreased. Indeed, larger numbers of 10 samples seem to improve the overall accuracy (See Table 9). Compared with the ensemble approach33, the MCDS approach showed a good balance between the segmentation accuracy, computation time, and accuracy of the predictive uncertainty.

Compared with the baseline model7, this study showed a potential improvement when increasing the depth of the segmentation model and the number of training data. Increasing the training data to larger than 20 cases improved overall, as shown in Fig. 4. Other studies have also investigated the segmentation of thigh muscles from CT images48,49,50. However, the number of cases was smaller, making the comparison invalid. Recently, Kim et al. attempted a 3D UNETR47 for the segmentation of the full thigh muscles22. The model was trained on a larger dataset (60 cases) and tested on 12 cases; however, the dataset included only patients with hip fractures, and it showed lower accuracy (DC=0.84; ASSD=1.419±0.91 mm). These comparisons collectively emphasize the higher accuracy of the improved model and the uniqueness of our fully annotated database (DB#1) and validation of external databases (DB#2-4) regarding the number of cases and the diversity of disease, patient positioning, and imaging conditions.

The assessment of the volume and intensity of the muscles and bones are among the ultimate goals of automated MSK image segmentation. In particular, the mean HU measured at abdominal muscles has shown a higher potential to predict age-related adverse outcomes compared with the muscle area9. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the accuracy of these measurements in automatically segmented hip and thigh MSK structures in CT images. High accuracy of the volumes and mean HU of most muscles and bones in HOA patients was obtained. Furthermore, the validation experiment on the four databases showed the robustness of the improved model in the segmentation of the GMED muscle with respect to the multi-manufacturer/scanners and disease variations. These findings indicate the potential usability of the segmentation model for hip-to-knee MSK assessments in clinical routines. The rapid inference time (∼3 min) of the entire CT volume adds to the model’s practicality for adoption in surgical planning or musculoskeletal simulation platforms. Furthermore, the muscle-wise density visualization depicted in Fig. 7 would help in the rapid and comprehensive assessment of muscle quality under several conditions, such as hip OA, cancer, sarcopenia, and obesity23.

On the other hand, MSK segmentation approaches in magnetic resonance images (MRIs) are attracting attention due to patient safety and high soft tissue contrast51,52, and the possibility of quantifying the muscle/fat composition using special sequences, such as Dixon53. However, MRIs usually require a long scanning time, represent various characteristics based on the acquisition sequence, and cover limited fields of view (FOVs). This necessitates integrating multiple acquisitions and registration processing to assess the whole knee-to-hip52, which could be limited to a few research-purposed databases25.

This study has the following limitations. The 2D segmentation model, even though it has a rapid inference time, does not capture the 3D information of neighboring structures, which affects the segmentation of small structures, such as the PI muscle. State-of-the-art 3D models, such as nnUNet54 or swin UNETR55, may potentially improve the segmentation of the small muscles; however, those models are known for their higher computational cost and longer inference time than their 2D counterparts56. This study did not investigate those models because it aimed to explore the potential improvements in the baseline 2D model and its predictive uncertainty, leveraging its fast inference time for large-scale analysis. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate the potential of 3D models to improve the segmentation accuracy of small structures. Furthermore, the small hip muscles (OI and OE muscles) showed low AUROC in failure detection based on the predictive uncertainty. The usage of the auto segmentations of those muscles requires attention in unannotated databases.

The failure detection approach and improved model (6layers,50) create a basis for several future directions in our research. The model’s potential in analyzing the disease progression of individual bones and muscles in large-scale databases of unannotated CTs will be investigated. Cases with segmentation failures could be detected based on the predictive uncertainty and excluded or refined by human annotators for downstream MSK analyses. Furthermore, the extension of the segmentation model to predict the MSK structures in other regions, such as the abdomen and back muscles, is currently under development. Furthermore, a few muscles in the hip, such as the quadratus femoris and Gemelli muscles, were not addressed, besides combining several muscles, such as the adductors, into a single label due to the challenging boundary definition. These structures will be addressed in our future work by involving higher-resolution images, such as from photon-counting CTs. This study focused on hip OA as a target MSK pathology. As the model has shown possible dependency on the disease severity in the large-scale analysis, we plan to further investigate its performance on other muscle pathologies, such as muscular dystrophy13, cachexia14, and sarcopenia15.

Conclusions

This study validated a DL model for MSK segmentation with uncertainty estimation in clinical CT images. The improved model (6layers,50) allowed for the automated, rapid, and accurate assessment of the volume and density of the hip and thigh bones and muscles from clinical CT images. The study has shown an impact of the disease severity on the model’s performance, and the usability of the predictive uncertainty as a tool for predicting the segmentation accuracy and failure detection in individual MSK structures at unannotated CT image databases. The high segmentation and muscle volume/density estimation accuracy, along with the high accuracy in failure detection, exhibited the model’s reliability for the analysis of individual MSK structures in large-scale CT databases.

Data availability

The datasets and the pre-trained models used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Fully automated deep learning tool for sarcopenia assessment on ct: L1 versus l3 vertebral level muscle measurements for opportunistic prediction of adverse clinical outcomes. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 218, 124 (2022).

Islam, S. et al. Fully automated deep-learning section-based muscle segmentation from ct images for sarcopenia assessment. Clin. Radiol. 77, e363–e371 (2022).

Bridge, C. P. et al. A fully automated deep learning pipeline for multi–vertebral level quantification and characterization of muscle and adipose tissue on chest ct scans. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 4, e210080 (2022).

McSweeney, D. M. et al. Transfer learning for data-efficient abdominal muscle segmentation with convolutional neural networks. Med. Phys. 49, 3107–3120 (2022).

Yokota, F. et al. Automated ct segmentation of diseased hip using hierarchical and conditional statistical shape models. In Mori, K., Sakuma, I., Sato, Y., Barillot, C., Navab, N. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention MICCAI 2013, vol. 8150 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40763-5 24 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Yokota, F. et al. Automated muscle segmentation from CT images of the hip and thigh using a hierarchical multi-atlas method. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-018-1758-y (2018).

Hiasa, Y. et al. Automated muscle segmentation from clinical ct using bayesian u-net for personalized musculoskeletal modeling. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2019.2940555 (2020).

Taghizadeh, E. et al. Deep learning for the rapid automatic quantification and characterization of rotator cuff muscle degeneration from shoulder ct datasets. Eur. Radiol. 31, 181–190 (2021).

Graffy, P. M. et al. Deep learning-based muscle segmentation and quantification at abdominal ct: application to a longitudinal adult screening cohort for sarcopenia assessment. Br. J. Radiol. 92, 20190327 (2019).

Kamiya, N. et al. Surface muscle segmentation using 3d u-net based on selective voxel patch generation in whole-body ct images. Appl. Sci. 10, 4477 (2020).

Iwasa, M. et al. Artificial intelligence-based volumetric analysis of muscle atrophy and fatty degeneration in patients with hip osteoarthritis and its correlation with health-related quality of life. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 18, 71–78 (2023).

Uemura, K., Takao, M., Sakai, T., Nishii, T. & Sugano, N. Volume increases of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and thigh muscles after hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 31, 906–912 (2016).

Hirayama, M., Ayaki, T., Yoshii, D., Yasuda, K. & Takahashi, R. Utility of skeletal muscle ct in diagnosing spinal muscular atrophy type 3 in a patient who had been undiagnosed for 50 years. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38709 (2023).

Ko, H. S. & Attenberger, U. Medical imaging in cancer cachexia. Die. Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00117-024-01346-5 (2024).

Nowak, S. et al. End-to-end automated body composition analyses with integrated quality control for opportunistic assessment of sarcopenia in ct. Eur. Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08313-x (2021).

Pu, L. et al. Automated segmentation of five different body tissues on computed tomography using deep learning. Med. Phys. 50, 178–191, https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15932 (2023). https://aapm.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/mp.15932.

Dabiri, S. et al. Muscle segmentation in axial computed tomography (ct) images at the lumbar (l3) and thoracic (t4) levels for body composition analysis. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 75, 47–55 (2019).

Pickhardt, P. J. et al. Automated abdominal CT imaging biomarkers for opportunistic prediction of future major osteoporotic fractures in asymptomatic adults. Radiology 297, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200466 (2020).

Hashimoto, F., Kakimoto, A., Ota, N., Ito, S. & Nishizawa, S. Automated segmentation of 2D low-dose CT images of the psoas-major muscle using deep convolutional neural networks Radiol. Phys. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12194-019-00512-y (2019).

Ogawa, T. et al. Validation study of the CT-based cross-sectional evaluation of muscular atrophy and fatty degeneration around the pelvis and the femur. J. Orthop. Sci. 25, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2019.02.004 (2020).

Wasserthal, J. et al. Totalsegmentator: Robust segmentation of 104 anatomic structures in ct images. Artif. Intell. Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.230024 (2023).

Kim, H. S. et al. Precise individual muscle segmentation in whole thigh ct scans for sarcopenia assessment using u-net transformer. Sci. Reports 14, 1–11 (2024).

Aubrey, J. et al. Measurement of skeletal muscle radiation attenuation and basis of its biological variation. Acta Physiol. 210, 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12224 (2014).

Cawthon, P. M. et al. Do muscle mass, muscle density, strength, and physical function similarly influence risk of hospitalization in older adults?. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 1411–1419 (2009).

Fitzpatrick, J. A. et al. Large-scale analysis of iliopsoas muscle volumes in the UK Biobank. Sci. Reports 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77351-0 (2020).

Kakihara, D., Nishie, A., Machitori, A. & Honda, H. The japan medical imaging database (j-mid). In Epidemiologic Research on Real-World Medical Data in Japan: Volume 1, 87–93 (Springer, 2022).

Li, D., Yang, Y., Song, Y.-Z. & Hospedales, T. M. Deeper, broader and artier domain generalization In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.03077 (2017).

Liu, P. et al. Deep learning to segment pelvic bones: large-scale ct datasets and baseline models. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 16, 749–756 (2021).

Selim, M. et al. Cross-vendor ct image data harmonization using cvh-ct. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, vol. 2021, 1099 (American Medical Informatics Association, 2021).

Roa, A. M. A., Andersen, H. K. & Martinsen, A. C. T. Ct image quality over time: comparison of image quality for six different ct scanners over a six-year period. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 16, 350–365 (2015).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. Int. Conference Mach. Learn. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.02142 (2016).

Sudlow, C. et al. Uk biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Mehrtash, A., Wells, W. M., Tempany, C. M., Abolmaesumi, P. & Kapur, T. Confidence calibration and predictive uncertainty estimation for deep medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 3868–3878 (2020).

Wickstrøm, K., Kampffmeyer, M. & Jenssen, R. Uncertainty and interpretability in convolutional neural networks for semantic segmentation of colorectal polyps. Med. Image Anal. 60, 101619 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Yang, C., Schweidtmann, A. & Tao, Q. Efficient bayesian uncertainty estimation for nnu-net. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 535–544 (Springer, 2022).

Okano, K., Kawahara, N., Chiba, K. & Shindo, H. Radiographic joint space width in patients with crowe type-i dysplastic hips. Clin. Orthopaedics Related Res. 466, 2209–2216 (2008).

Kellgren, J. H. & Lawrence, J. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheumatic Dis. 16, 494 (1957).

Vallieres, M., Freeman, C. R., Skamene, S. R. & El Naqa, I. A radiomics model from joint fdg-pet and mri texture features` for the prediction of lung metastases in soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Phys. Med. Biol. 60, 5471 (2015).

Jinzaki, M. et al. Development of upright computed tomography with area detector for whole-body scans: phantom study, efficacy on workflow, effect of gravity on human body, and potential clinical impact. Investig. Radiol. 55, 73 (2020).

Masuda, M., Soufi, M., Otake, Y. et al. Automatic hip osteoarthritis grading with uncertainty estimation from computed tomography using digitally-reconstructed radiographs. Int J CARS 19, 903–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-024-03087-1 (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929 (2020).

Kikinis, R., Pieper, S. D. & Vosburgh, K. G. 3d slicer: a platform for subject-specific image analysis, visualization, and clinical support. In Intraoperative imaging and image-guided therapy, 277–289 (Springer, 2013)

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International conference on machine learning, 448–456 (pmlr, 2015).

Lin, L.I.-K. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics 45, 255–268 (1989).

Hiasa, Y. Bayesian U-Net: Keras implementation. Github. https://github.com/yuta-hi/keras_bayesian_unet/ (2019).

Chollet, F., et al. Keras. GitHub. https://github.com/fchollet/keras (2015)

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Unetr: Transformers for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 574–584 (2022).

Molaie, M. & Zoroofi, R. A. A knowledge-based modality-independent technique for concurrent thigh muscle segmentation: Applicable to ct and mr images. J. Dig. Imaging 33, 1122–1135 (2020).

Molaie, M. & Zoroofi, R. Thigh muscle segmentation using a hybrid FRFCM-based multi-atlas method and morphology based interpolation algorithm*. IET Image Process 15, 2572–2579. https://doi.org/10.1049/ipr2.12245 (2021).

Nishiyama, D. et al. Deep generative models for automated muscle segmentation in computed tomography scanning. Plos One 16, e0257371 (2021).

Andrews, S. & Hamarneh, G. The generalized log-ratio transformation: learning shape and adjacency priors for simultaneous thigh muscle segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 34, 1773–1787 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Hybrid representation-enhanced sampling for bayesian active learning in musculoskeletal segmentation of lower extremities. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-024-03065-7 (2024).

Taniguchi, M. et al. A higher intramuscular fat in vastus medialis is associated with functional disabilities and symptoms in early stage of knee osteoarthritis: a case–control study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 25, 1–9 (2023).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnu-net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 203–211 (2021).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Swin unetr: Swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in mri images. In International MICCAI brain lesion workshop, 272–284 (Springer, 2021)

Zhang, Y., Liao, Q., Ding, L. & Zhang, J. Bridging 2d and 3d segmentation networks for computation-efficient volumetric medical image segmentation: An empirical study of 2.5 d solutions. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.06163 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers JP19H01176, JP20H04550, JP21K16655, JP21K18080, JP17H04266, JP17K16482, JP20K08056, JP21H03799, and JP23K07214), Uehara Memorial Foundation, and the Takeda Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. drafted the manuscript, conducted the experiments, and performed the data analysis. Y.O., M.I., K.U., M.T., N.S, and Y.S. made a substantial contribution to the study design and data collection. T.H., M.H., Y.Y., M.Y., Y.Y., S.O., M.J. contributed to data collection. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Masahiro Jinzaki received a grant from Canon Medical Systems. However, Canon Medical Systems was not involved in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the institutions participating in this study (IRB approval numbers: 21115 for Osaka University Hospital, 2023-28 for Hitachi Health Care Center, 2020-M-7 for Nara Institute of Science and Technology, and jRCTs032180267 for Keio University.)

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soufi, M., Otake, Y., Iwasa, M. et al. Validation of musculoskeletal segmentation model with uncertainty estimation for bone and muscle assessment in hip-to-knee clinical CT images. Sci Rep 15, 125 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83793-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83793-7

This article is cited by

-

Lower-limb muscle mass quantification and whole-body muscle loss detection using preoperative computed tomography images in patients with hip disease

International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery (2025)