Abstract

The Urmia Lake Basin has been severely affected by the unbalanced exploitation of water resources. To better manage the use of integrated water resources, the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT was adopted for the Mahabad Plain in the Urmia Lake Basin, N.W. Iran. The results indicated that a multifunctional calibration of SWAT and MODFLOW-NWT hydrological models in a large-scale irrigated area was necessary, using parameters such as evapotranspiration and crop yield in addition to the usual surface runoff and water table measures. The coupled model was then used to evaluate several water allocation scenarios, such as alternate proportions of irrigation water allocation from conjunctive water resources. The ultimate objective of adopting these scenarios was to increase the residual share of the water supply in order to compensate for the deprived share of Urmia Lake. The results of this study demonstrated that that the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model was able to satisfactorily simulate the surface and groundwater balance components at different spatial and temporal dimensions. The results indicate that the Mahabad aquifer is capable of supplying irrigation water needs in the central and northern regions, with some limitations around running rivers. Furthermore, groundwater sustainability indicators showed that even with an additional 30% of the water supply from groundwater, the long-term sustainability of groundwater resources was preserved Ultimately, the findings indicated that a reduction in water allocation from surface waters can lead to an increase in water release to the lake of 16 million cubic meters (21%) to 18 million cubic meters (25%) in different years. The outcomes of this study can serve as a guiding principle for the optimal and sustainable allocation of surface and groundwater resources in highly competitive and fragile basins such as Lake Urmia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surface and groundwater resources interact continuously at different spatial and temporal scales, and they are used in the agriculture sector in many plains. It is important, therefore, accurately to delineate the components of the surface water and groundwater balance. The recharge and abstraction of surface and groundwater resources are unique challenges in this regard due to the location of rivers, wells, and human intervention in the management of irrigation water supply in different areas1,2,3,4,5.

The sustainable use of water resources, especially in conditions of water scarcity, requires a complete and comprehensive understanding of their ambiguous and complex situation. This knowledge requires the use of a tool capable of taking into account all the processes in both surface and subsurface systems6,7,8. It is important to use a comprehensive model of surface water and groundwater resources in order to simulate agricultural water supply in areas where water resources are consolidated. The main question is whether this model will be able to simulate hydrological processes, including surface runoff and water table, in the exploitation of combined surface water and groundwater resources. Is the integrated model capable of simulating the interaction and exchange of surface water and groundwater between the river and the aquifer? Furthermore, by applying different withdrawal scenarios in different regions and temporally in the combined model, it is possible to extract the best exploitation patterns according to the desired goals of each study. A comprehensive model with specific characteristics of temporal and spatial scale that can estimate the effectiveness of integrated operation patterns on water balance components will provide the necessary infrastructure to resolve inconsistencies between supply and demand of water resources in the study area9,10,11. Despite the rapid expansion of numerical models over the past decade, there is still a need for an integrated model to provide for a better assessment of surface water and groundwater balance components7,8,12,13. Combined surface water and groundwater models are especially important for connecting saturated and unsaturated water balance5,7,14.

The MODFLOW model (the USGS Modular Three-Dimensional Finite-Difference Ground-Water Flow Model) has been widely used as a standard model for simulating groundwater flow fluctuations in steady and transient states15,16,17,18,19. In this model, recharge values are commonly defined as a predetermined percentage of rainfall and total irrigation water6,20. Studies have demonstrated that the uncertainty in determining this parameter will significantly impact the groundwater recharge and consequently the water flow in the long-term simulation of an aquifer20,21. There are several methods for determining the amount of groundwater recharge. The SWAT model (The Soil and Water Assessment Tool), a comprehensive surface water simulation model, is capable of estimating the actual evapotranspiration and recharge from rainfall and irrigation water at Hydrological Response Units (HRUs) and the basin scale1,5,7,10,11,13,14,22.

Studies have demonstrated that coupled SWAT and MODFLOW-NWT models can more accurately simulate the exchange of surface water and groundwater5,7,8,11,23. Estimates of soil infiltration as a recharge can be more precisely estimated by using coupled SWAT-MODFOW-NWT2,4,5,8. The existing limitations of the two models, namely the inadequate estimation of recharge in the MODFLOW-NWT model, and the subsurface flows in the SWAT model can be resolved when they are used together. The coupled model can also reflect the temporal and spatial characteristics of the region3,7,8. The coupled model also has the advantage of examining balance components at both the temporal and spatial scales, such as the interaction between surface water and groundwater. It is also feasible to manage changes in the water table and hydraulic gradient of groundwater under management strategies, such as the rate of withdrawal from surface and groundwater under different13,24.

Many studies have been conducted using the combined SWAT-MODFLOW model have in small or large watersheds in order to estimate water balance components and examine different management scenarios of water resources exploitation5,7,10,13,22,25,26,27,28,29,30. Surveys have shown that the use of comprehensive and integrated models of surface and underground water resources such as SWAT-MODFLOW can be a useful tool for examining the water balance components and evaluating the implementation of different management and exploitation scenarios2,11,31,32,33,34. However, the data must have sufficient temporal and spatial distribution (including soil data, land use data, irrigation management data, and integrated supply of irrigation from surface water and groundwater sources, etc.). Because the uncertainty in the use of the data will be effective in achieving the desired outcomes and estimating the components of the water balance13,35,36,37. These models can be used as a guide for optimal allocation and as a practical tool for explaining the pattern of sustainable and appropriate exploitation of consolidated surface water and groundwater resources under the influence of different management scenarios in competitive and highly fragile basins27,38,39,40.

The scope of activities related to water resources and operations suggests that adequate attention is not being given to integrated planning and management of water resources. Furthermore, due to the spatial and temporal imbalances in the distribution of water resources and the limitations of surface water use, it is necessary to investigate the operation of both surface water and groundwater resources. In recent decades, the supply of water required from groundwater resources has led to the development of management strategies for the conjunctive use of surface water and groundwater resources. Specifically, in the Urmia Lake basin, which has been impressed by the unconventional operation of water resources, these models can be used to maximize the water supply of Urmia Lake according to the pattern of supplying irrigation requirements of agricultural lands from integrated sources. In most previous studies, the calibration of the coupled model has been performed based on groundwater level and runoff. In areas under intensive agriculture, less attention has been given to the calibration of the model based on evapotranspiration and crop yield. The multi-objective calibration can have a significant impact on the simulation results41. The main objective of this study was to assess the simulation of surface water and groundwater components by using a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model under multi-purpose calibration of surface runoff, evapotranspiration, crop yield, and groundwater table in the Mahabad plain located in the Urmia Lake basin, Iran. Balance components are strongly influenced by recharge and discharge in different years. Therefore, the components of surface water and groundwater balance will be analyzed in different years in the study. In the following, the appropriate integrated operation pattern of integrated surface water and groundwater resources was investigated using the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model, considering the limitations of consumption and the priorities of allocation of water resources in the study area. This is accomplished by determining the maximum safe extraction of groundwater in order to supply irrigation requirements in different temporal and spatial intervals in different hydrological years. This is done by maintaining a long-term relative balance of the water table and without any negative impact on river flows in different zones of the plain. The main challenge was to identify the regions with the highest potential for groundwater withdrawal, based on the contour lines of the water table. Previous studies have failed to account for this level of detail in exploitation patterns. In the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model, several scenarios were adopted for the conjunctive use of surface water and groundwater resources, and results were evaluated based on groundwater sustainability indicators. The objective was to reduce the share of irrigation supply from surface water and, as a result, increase the share of inflow to the lake without changing the amount of irrigation water supply.

Results and discussion

Parameterization, sensitivity, uncertainty analysis, calibration and validation

SWAT model

According to Abbaspour et al.42, the calibration of the hydrological model (SWAT) solely based on stream flow is insufficiently precise to accurately determine the components of surface water balance in an irrigated area. The crop parameters have a direct impact on the actual evapotranspiration of crops (ETa) and their crop yield. Therefore, the data of ETa and crop yields of major crops of the region, namely wheat, barley, sugar beet, corn, alfalfa, apple, and grapes, were used to improve the model results. Various parameters can affect the simulation of stream flow, ETa, and the yield of crops. Many parameters were selected based on a comprehensive review of studies conducted by the SWAT model43,44,45,46,47. The most sensitive parameters for the stream flow, evapotranspiration, and crop yield simulation were determined through sensitivity analysis and included in the calibration process. The sensitivity analysis of the SWAT model resulted in the selection of 43 of the most sensitive parameters about the accuracy of stream flow estimation, evapotranspiration, and crop yield. These parameters were taken into account during the calibration and automatic uncertainty analysis of the SWAT model using the SUFI2 algorithm as an inverse modeling technique. Overall, the most important parameters were related to groundwater (.gw), basin (.bsn), sub-basin (.sub), hydrological responsible unit (.hru), and soil (sol.). The most sensitive parameters in the hydrological calibration period were the SCS runoff curve number for moisture condition II (CN2), and effective hydraulic conductivity of channel (CH_K2), Water transfer losses (TRNSRCH) were the most sensitive parameters in the hydrological calibration period. The obtained outcomes are in accordance with the findings of previous studies14,20,44,48,49,50. The potential heat units for plants growing at the beginning of the simulation (heat units) also were found to be one of the most sensitive parameters for the proper simulation of ET and yield of crops Furthermore, the leaf area index (LAI) and harvest index (HI) were used for the proper estimation of crop yields during the calibration process of the model. The effective parameters, after performing a sensitivity analysis, and their final range after calibration are given in the supplementary information file (Appendix 1).

MODFLOW-NWT model

Numerous parameters are involved in the simulation of groundwater flow and must be assessed for their sensitivity in the simulation model. The sensitivity analysis of five hydraulic conductivity (K), specific yield (Sy), recharge (RCH), pumping rate (Q), and river bed hydraulic conductivity coefficient (Cod.) was investigated due to their maximum effect and high uncertainty in the model. The investigation of sensitivity analysis revealed that the amount of Sy affects the temporal distribution of errors and the parameters of K and coefficient of riverbed conductivity (Cod.) mainly affect the spatial distribution of errors. Hydraulic conductivity (K) and specific yield (Sy) were found to be the most sensitive parameters related to the simulation of the groundwater level. Furthermore, the recharge parameter can have a significant impact on the water table fluctuations. Like hydraulic conductivity, it had high sensitivities. The above parameters discussed so far can affect the simulation of the water table for the entire region, but the conductivity coefficient of the riverbed can affect readings from piezometers along the river shores. The conductivity coefficient of the riverbed was found to have a lower sensitivity than other parameters. Taheri tizero and Kamali51 and Hamraz et al.52 also showed that the model was highly sensitive to changes in hydraulic conductivity (K) and behaved similarly to specific yield (Sy). Koohestani et al.53 also indicated that, if the values of K and Sy are properly defined in the conceptual model, the error introduced in the estimation of the groundwater level will be minimal. Furthermore, the recharge parameter can affect the fluctuations of the water table. The sensitivity was similar to hydraulic conductivity. Further detailed information of the MODFLOW-NWT model can be found in Appendix 2 in the supplementary information file.

Stream flow

In this study, the SWAT model was evaluated under different weather conditions in order to determine the temporal distribution of recharge and discharge over a ten-year period in the Mahabad Plain. Figure 1 shows the results of the criteria used to evaluate the Gerdyaghoub hydrometric station. In general, the findings indicate that the P-factor and R-factor criteria obtained during in the process of checking model uncertainty were acceptable. Based on the statistical indices of R2, NS, RMSE, and PBIAS, the results showed that the SWAT model was able to simulate run-off, which had a low flow most of the time, especially during the calibration period. The statistical indices in the validation period were even significantly than the results of the calibration period. During the calibration and validation periods, the average flow rate measured at this station was reported to be 1.1 m3/s and 6.2 m3/s respectively. In low river flows, the model was highly unstable, which led to overestimation. In this study, the model has over-estimated run-off by about 4.5% during the calibration period, and under-estimated the run-off by about 1.6% during the validation period. Moriasi et al.54 reported that the model is well capable of estimating the run-off when the PBIAS is less than 10%. A review of several studies has shown that the value of groundwater withdrawal and the impact of human activities along the rivers influence the run-off simulation by SWAT1,45,55,56. Furthermore, the simulation models have poor performance in estimating the runoff at low flow rates. This problem can be attributed to the many simplifying assumptions in simulating surface water models, such as the SWAT model, and the complex interaction between surface and sub-surface flows in areas with low rainfall57. It should be noted that the modeling of run-off in semi-arid and arid regions is more complex than in wet regions due to the low flow these regions, and flow continuity is established solely for rainfalls with a significant value44,55,58.

Figure 1 presents the average monthly flow rates for the calibration and validation periods for the Gerdyaghoub station. The calibration of the SWAT model was a big challenge for smaller regions characterized by a seasonal river in the plain. The ecological equilibrium of the Mahabad river basin is significantly disturbed by human activities. During the period of 2009–2018, there has been a significant increase in activities involving land use, over-use of surface water and groundwater, and increased water allocation in the agricultural, industrial, and rural sectors. Consequently, the SWAT simulation of the river base flow was not readily feasible for the initial calibration. Furthermore, the peak river flow was often highly overestimated. For this study, the base flow of the river was determined using the Mahabad dam release flow information. The base flow was then separated from the total flow and added to the model59,60. Other limitations, such as the lack of well-distributed rain gauge stations in the plain46, or the lack of accuracy in quantifying various human activities, such as unauthorized withdrawals from the Mahabad River56, inadequate physical nature of the SCS method in estimating the runoff from snow melt61 can affect the hydrology of the region. Further details of the stream flow simulation can be found in Appendix 3 of the supplementary information file.

Actual evapotranspiration (ETa), and crop yield

In addition to stream flow, actual evapotranspiration (ETa) and crop yields for wheat, barley, corn, sugar beet, alfalfa, apple, and grape were used for the evaluation of the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model. For the simulation period, there were no direct field evapotranspiration data for the major crops. Therefore, an evaluation of the model for estimating ETa was performed using the ETa results obtained from WaPOR (The FAO Water Productivity Open-access portal) using satellite image processing62. The ETa estimations from the WaPOR model were obtained by pairing the WaPOR images with land use maps for different crops. The crop yields simulated by the coupled model are compared with the reported data from the Agriculture Organization of West Azerbaijan Province (AOWAP). Figures 2 and 3 present scatterplots of the ETa and crop yields for wheat, barley, corn, sugar beet, alfalfa, apple, and grape for the period 2009–2018.

The performance of the coupled model in estimating ETa for calibration and validation periods indicated that the model was well capable of simulating the ETa. In summary, a comparison of the results obtained from the model and WaPOR shows that, for the majority of crops, the estimated ETa values are close to the results obtained from WaPOR. Nevertheless, the WaPOR ETa values are typically higher than the estimates values from the model. Generally, the results show a good correlation between the two estimations. The RMSE between the simulated and observed values showed a high efficiency of the model. Bennour et al.63 and Herman et al.64 indicated that the new approach of using remote sensing ETa is efficient for calibration and validation of an eco-hydrological model for a basin with limited data. These openly accessible satellite-derived ETa datasets give a very good performance. The findings of Alizadeh et al.65 and Ahmadzadeh et al.66 also confirm the efficacy of the SWAT model in estimating ETa. Other studies also suggest that the estimated ETa by the SWAT model can serve as a benchmark for assessing the outcomes of remote sensing techniques63,67,68,69.

The results demonstrated that the model was capable of estimating the yield of crops based on the irrigation supply in different hydrological years. For example, yields were lower in the dry year (2016) than in the wet year (2018) for all crops. The yield values estimated by the model for different years are close to the yield values of crops reported by the AOWAP. Eini et al.43 and Musyoka et al.70 demonstrated that using of crop yields in calibration and validation periods were robust and gave a very good performance. Further details of the actual evapotranspiration (ETa), and crop Yield simulation can be found in Appendix 3 of the supplementary information file.

Groundwater table

The performance of the coupled model in estimating the water table for calibration and validation periods indicated that the model was well capable of simulating the water table (Table 1). The coefficient of determination, R2 values, indicate a significant correlation between the observed and simulated values of the water table. The results of the RMSE, based on piezometers readings of the water table fluctuations, showed that the error value was 0.35 and 0.34 m for the calibration and validation periods, respectively. The error value of less than one meter is deemed satisfactory and appropriate result for the region. The errors obtained were acceptable for the majority of piezometers. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of the errors was almost uniform throughout the aquifer. If the NS value is close to one, then the model will be more efficient. Based on this indication, it can be inferred that the model has been adequately calibrated and validated. Overall, the results indicated that the model simulates the water table well for both periods.

Figure 4 presents the results of the simulated and observed groundwater level values for all 22 piezometers. The results obtained from both calibration and validation periods showed that there is a good correlation between the simulated and observed water tables. All piezometer hydrographs demonstrate that the model was able to accurately estimate the seasonal and long-term trend of the groundwater level change by taking into account the change in the value of recharge and discharge from the aquifer based on the land use and irrigation pattern during the simulation period. To ensure that there is no significant error in the fluctuations of the water table in most of the piezometers between the simulated and observed values. The findings of other studies also illustrate the significance of the developed integrated modeling tool in quantifying the impact of changes in surface water and groundwater resources on its subsurface water system25,26,32.

Surveys indicated that 16 out of 22 piezometer wells displayed a RMSE error of less than 0.4 m compared with the observed values. This indicates the high accuracy of the model calibration. Studies have also demonstrated that the use of a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model can be a useful tool for the simulation of the water table and the groundwater balance components2,11,31,32,33. The existing differences and contradictions can be attributed to errors in recording the discharge of wells, sudden changes in the water table, and human error in recording the water table in observation wells13,36,37, and unavoidable errors in estimation of hydrodynamic coefficients such as hydraulic conductivity and specific yield34,71. Furthermore, it is not inaccurate to assume that the physical properties of an aquifer in a 500 m × 500 m grid cell are unique. In addition, if the observation well is located at the edge of the grid cell, the simulated water table in the center of each cell will probably be different from the observed value5. Further details on the accuracy of the model in simulation of the water table fluctuations can be found in Appendix 4 in the supplementary information file.

It should be noted that, in addition to the optimal determination of the parameters of hydraulic conductivity and the specific yield, tributary seasonal streams, were also introduced into the simulation process. The input data for these streams were taken from the SWAT model. The tributary stream flows can directly affect the fluctuations of the localized water table4,11. Recharge values are one of the primary and crucial input important input components in groundwater modeling in semi-arid and arid regions. In the coupled model, the recharge values obtained from the SWAT model were used in the calibration process of the MODFLOW-NWT model. The results indicate the reliability of the adopted procedure for determining the value of recharge, and improve its effect on the estimation of the fluctuations of the water table. This has also been confirmed by other researchers2,8,35,72.

Adoption of water allocation scenarios

Groundwater level fluctuation and values of drop in water table

The objective of this study was, after adoption and evaluation of the coupled conjunctive surface and groundwater SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT simulation model, to examine a series of scenarios in increasing the share of groundwater to supply irrigation water and evaluate their outcome on the fate of surface water release to the lake while establishing sustainability for the groundwater. The adopted scenarios showed that an increased share of irrigation water supply from groundwater (by 10%, 20%, and 30%), will result in a decline in the groundwater table. The water table drops in the central and northern areas of the plain are greater than those in the eastern and southern regions, where the proportion of irrigation water supplied from combined water sources remained unchanged. Changes in the water table in piezometers after applying the current condition, scenarios 1, scenarios 2, and scenarios 3 can be found in Appendix 4 in the supplementary information file.

The coupled model was used to calculate values of drop in the water table at the location of piezometers (Scenario 1, Scenario 2, and Scenario 3). In the southern and eastern regions of the plain, a groundwater drop also occurred (Fig. 5) because of the hydraulic connection between the cells. This resulted in fluctuations in the water table in the central and northern regions of the plain from the increased share of irrigation water supply from groundwater sources. The central and northern regions of the plain had different values for water table drops. The higher water level dropped in areas with higher densities of wells (such as in Arazi_Darlak, Arazi_Daryaz, Arazi_Gerdgeroy, Gapiss, and Ghezlgapi-Gharegashlagh). Nevertheless, the water table drop in proximity to the Mahabad river is lower due to the creation of a reverse hydraulic slope and the recharge from the river to the groundwater (namely Arazi_Ghezelgapi, Egirghash, Darlak, and Ghomghaleh_Koreh). The surveys indicate a lower water table drop in Arazi Koseh_Kahriz, Serah_Ghezlgapi, Gharegashlagh, Koseh_Kahriz, Gerdgroy, and Kohneh_Deh. The density of wells and groundwater withdrawal rates are lower in these regions than in other areas (Fig. 5). Yifru et al.34 found that groundwater pumping significantly impacts stream flow at the beginning of the irrigation period. Under affected environmental flow management and with an average groundwater level fluctuation of one meter, the exploitable groundwater during the irrigation period can reach up to 2.96 Mm3/day. With this amount of pumping, the average groundwater discharge to streams declined by around 13%. While groundwater level fluctuations near the watershed outlet were minimal, in the upstream area, levels could decrease by as much as 2.5 m. The groundwater level fluctuation underscores the necessity of accounting for both spatial and temporal factors, particularly in highly affected regions.

Values of drop in water table calculated by the coupled model at the location of piezometers (Scenario 1, Scenario 2, and Scenario 3: Irrigation water allocation was reduced by 10, 20, and 30 percent reduction in surface water resources, and the same amount of groundwater resources increased to preserve the total amount of allocation.)

The value of water flow rate to Urmia Lake

Table 2 presents the total surface flow value in the current situation and after applying scenarios 1, 2, and 3. The hydrograph at the Gerdyaqoub station for the existing conditions and after applying scenarios 1, 2, and 3 shows that the flow of water has increased in different years. Specifically, due to an increase in the share of irrigation supply from groundwater, the flow of water from the Gerdyaqoub station to the lake was more than in the existing condition. Investigations indicate that an increased allocation of groundwater for irrigation will result in an extra recharge from the river to the groundwater. The seepage in a wet year is more than a normal year, and its value in a normal year is more than in a dry year. Gao et al.73 also suggested that surface water resources could be supplementary irrigation sources to mitigate the water resources scarcity in the Big Sunflower River Watershed (BSRW). It was found that the proportion of sub-basins in BSRW with stream water resources was 21% in dry years, while this increased to 35% in normal years and 57% in wet years.

Therefore, by applying each scenario, the value of flow at the Gerdyaqoub station towards the lake will increase. However, by applying scenario 3, the release rate of water to the lake in a dry year (2016–2017) could increase by 10.30 million cubic meters per year (MCM/year) compared to the existing conditions. The surface flow increases in normal (2017–2018) and wet (2018–2019) years is estimated at 12.60 and 15.10 MCM/year, respectively (Table 2). The value of flow release in the current situation and after applying the scenarios shows that the share of flow release to the lake has been significant in wet years, and is more in the dry years. However, the effectiveness of applying scenarios to increase the release of water to the lake in dry years is far more valuable. For example, during the hydrological years of 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 (dry years), the flow release from applying scenario 3 increased from 32.01 and 15.70 MCM/year to 45.11 and 28.60 MCM/year, respectively, representing an increase of 41% and 82%. Liu et al.26 also demonstrated that irrigation from groundwater led to enhanced streamflow by the SWAT-MODFLOW simulations. The SWAT–MODFLOW simulations can, therefore, lead to correct and more realistic assessments of the impacts of groundwater abstractions for irrigation on streamflow.

It should be noted that long-term simulation studies show that the water table would drop after applying scenario 3 for 10 consecutive years compared to the existing conditions by a range of 0.25 m to 0.95 m. It seems that this decrease is not significant, especially considering the high-water table in the northern and central areas of the Mahabad Plain. In addition, an increase in the share of irrigation supply from groundwater by more than 30% could decrease the allocation of irrigation supply from surface water, which could ultimately increase the release to Urmia Lake. However, excessive groundwater withdrawals in the long term could lead to an increase in the water table drop, which may eventually lead to unsustainable water resources in this region.

Surface water and groundwater interactions

One of the primary concerns related to the development of groundwater resources is the effect of groundwater pumping on streamflow. Therefore, investigating the spatio-temporal patterns of surface water leakage from the river to the aquifer or groundwater drainage from the aquifer to the river network is very important. A key output of the SWAT–MODFLOW-NWT model is a detailed surface water–groundwater interaction for each MODFLOW-NWT river cell in the aquifer74. The results indicate a significant difference in interaction between surface water and groundwater, especially for the cells located along the main river of Mahabad and the secondary streams each year. The values of the simulated interaction varied for nearly every river cell in the region. The spatial and temporal pattern of the value of recharge and discharge between the groundwater and the river network is not uniform, and it follows the pattern of annual rainfall, irrigation, and flows released from the Mahabad dam to the Urmia Lake. Therefore, the temporal variation of the interaction could be clearly observed in each hydrological year.

The results indicate that interactions between surface water and groundwater mainly lead to flow discharge from groundwater to the rivers in the central and northern parts of the aquifer, for which the depth of the water table is high (2 to 5 m), as compared to the southern and western parts of the aquifer (5 to 9 m). The topography is also nearly flat in the central and northern parts of the aquifer. In these areas, the rivers serve as drainage and discharge paths for the groundwater. Furthermore, the calibration process indicated that the river bed’s hydraulic conductivity value was significantly higher than in other regions, which led to a higher discharge from groundwater to surface streams. In general, within the river network of the region, the main river of Mahabad functions as a permanent river, whereas the streams function as a seasonal river. The distribution of the interaction pattern was consistent with the results of a previous study75. These variations were based on a multitude of factors, which mainly depend on the hydraulic head found at each of these river cells. The hydraulic conductivity of the aquifers can also affect the simulated surface water–groundwater interaction, especially in areas with variable conductivity. Xu and Beekman76 and Le Maitre and Colvin9 have demonstrated that the interaction between the aquifer and the river depends on several factors, including the value of recharge, the water table, the hydraulic conductivity of the riverbed, the storage coefficient, and the transferability of the aquifer. Further details on the accuracy of the model in simulation of the surface water and groundwater interactions can be found in Appendix 5 in the supplementary information file.

Groundwater sustainability indicators

The analysis of the groundwater sustainability indicators in the current situation and after applying scenarios 1, 2, and 3 showed that the dependence on groundwater (DG) index in the current situation is moderate (Table 3). After applying scenario 3, the dependence on groundwater remains moderate but it increases with the increase of groundwater irrigation supply (to more than 50%). Based on the GD index, the ability and potential of groundwater development in the Mahabad aquifer, indicate that it is in conditional development under the current conditions (33.4%). The GD index will increase to 42.8% following scenario 3, indicating the non-development of the aquifer. The index is still in close proximity to the threshold of 40% (conditional development). Hence, it appears that a 30% increase in irrigation supply from groundwater and a 30% decrease from surface water (scenario 3) is deemed a suitable scenario. The GDR index also indicates that the level of confidence in the long-term withdrawal of the aquifer decreases with the increase in the water table drop. After applying scenario 3, the GDR index will decrease to 61 years compared to the current situation (422 years). Furthermore, based on the aquifer sustainability index (AS), the aquifer will still remain sustainable after applying scenario 3. The ability of the aquifer to recover and return to normal conditions, as determined by the ARP index, indicates that this value is less than 10 in the current situation and after applying the scenarios. This indicates that the aquifer has a high recovery potential. Singh and Prashant77 also indicated the actual status of sustainability of groundwater, especially in the hyper-arid region of Rajasthan, by integrating all important indicators such as the development of groundwater sustainability index related to the protection and management of groundwater in the region.

Material and methods

The flowchart for this study is shown in Fig. 6. After defining the study area, the water supply status from combined surface and groundwater determined. The SWAT model was then selected as a comprehensive surface hydrological model to accurately estimate deep percolation and real evapotranspiration, and was linked to the MODFLOW groundwater model. The required data for each of the SWAT model and MODFLOW model were collected. Each of the models were separately calibrated and validated. Both the calibrated SWAT and MODFLOW models were coupled together. Finally, several practical scenarios were adopted due to the study objectives and run in the coupled model.

Study area

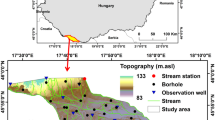

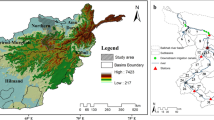

The Mahabadchay Basin (MCHB) is one of the sub-basins located in the northwest of Iran and southwest of the Urmia Lake Basin. It is the eighth sub-basin with an area of 1516 km2, which is about 2.9% of the total area of the Urmia Lake Basin (Fig. 7). In this area, the Mahabad dam is an important structure in the region, and the Mahabad irrigation and drainage network is located downstream. The Mahabad plain and aquifer are located in the Mahabadchay basin, which has an area of 275 and 253 km2, respectively. According to Domarten and Amberjeh’s drought coefficient, the climate of the region is a semi-arid climate.

During the statistical period 1990–2020, the average annual precipitation and the average annual evaporation from the pan were 402 mm and 1820 mm per year, respectively. In August and February, the average maximum and minimum monthly temperatures were 33.7 and -2.2 degrees Celsius, respectively. Precipitation amounts were 30.1%, 37.1%, 31.2%, and 1.6% during autumn, winter, spring, and summer according to this period.

According to the aquifer characteristics and the groundwater table obtained from 22 groundwater observation wells, the thickness of the bedrock ranges from 21 to 53 m from southwest to northeast, and the groundwater level varies from 1.5 m in the northern areas to 6.5 m below the ground surface in the south of the aquifer. The trend of groundwater level over the past 23 years (1996–2020) indicates that the water table has dropped by 1.5 m, or by an average of about 6 cm annually. Generally, the main trend of the plain water level in recent years (2014–2020) has been low, with a negligible annual decline. Groundwater evaporation is high due to the high groundwater table in the central and northwest regions of the plain. Groundwater recharge, by the infiltration of precipitation and deep percolation of applied irrigation, with the increased groundwater head creating a gradient that leads to discharge to the stream network and base flow for the river. Cultivation and associated irrigation occurred between March to September. Wheat, barley, corn, sugarbeet, alfalfa, apple, and grape are the major crops in the MCHB.

Development of the coupled SWAT‑MODFLOW-NWT model

MODFLOW-NWT has limitations in specifying the hydrological processes within the watershed. Hence, it is often linked with land surface models, such as SWAT5,7,8,13,78. Bailey et al. (2016) developed a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model with the source codes for SWAT 2012 and MODFLOW-NWT to better represent the river-aquifer interchanges. The SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT integrated modeling framework as proposed by Bailey et al.8 was used in this study. In the present coupled model, SWAT simulates the land surface and vadose zone, in-stream-, and soil domain processes in each HRU. Whereas, MODFLOW-NWT simulates groundwater hydrology in each grid cell, including groundwater level, a three-dimensional simulation of underground water flow, and interactions between surface and groundwater.

As indicated in Table 4, spatial (e.g., DEM, soil and land use), hydro-climate, and agricultural management data were used as inputs to SWAT. The main input data for the SWAT model consists of topography, soil physical properties, land use maps, and climate data. The soil data, conditioned and corrected digital elevation model (DEM), and land use maps were obtained from the global soil map of the Urmia Lake Restoration Plan (https://www.ulrp.ir/en/), and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)79,80.

In many studies, the calibration of the SWAT model has been performed only based on the data from hydrometer stations. According to Abbaspour et al.42, a multipurpose calibration method has been recommended to increase spatial accuracy. In this study, in addition to calibrating the model based on discharge values (Gerdyaghoub gage), simulated and observed crop yields and evapotranspiration for wheat, barley, corn, sugar beet, alfalfa, apple, and grape were compared with reported data from the Agriculture Organization of West Azerbaijan Province (AOWAP) for the period of 2009–2018. The SWAT model is evaluated by using field values, such as measurements through lysimeters or estimates from satellite image processing. Due to the lack of evapotranspiration field data, the SWAT estimated ET values were compared with the findings obtained from WaPOR (https://www.fao.org/in-action/remote-sensing-for-water-productivity/en). The calibration guidelines within the documentation for the SWAT-CUP software, which were used in this study, can be found in Abbaspour et al.57. Based on a Bayesian framework, SUFI2 quantifies the uncertainties through the sequential and fitting processes. In SUFI2, the parameter uncertainty is calculated from all sources such as the indeterminacy of input variables (e.g., rainfall data, temperature, and land use), the model structure, and measured data (e.g., surface runoff). Further details on the input data, and calibration processes of the SWAT model can be found in Appendix 6 in the supplementary information file.

The data of MODFLOW-NWT input can be seen in Table 5. The MODFLOW-NWT model relies on DEM, observation wells, pumping wells, bedrock properties, and boundary conditions. The MODFLOW-NWT model was developed using the Groundwater Modeling System (GMS) interface to prepare the input files required for the coupled SWAT-MODLOW-NWT model. Different sources of data were used in this study to determine hydrodynamic coefficients of the aquifer material including hydraulic conductivity (K), transmissivity (T), and specific yield (Sy), such as pumping tests and the grading of soil samples82. The process of MODFLOW-NWT calibration involves the modification of uncertain parameters, such as groundwater level, in order to achieve a minimal disparity between measured and simulated values. Initially, in this study, the calibration methodology for groundwater flow modeling using MODFLOW-NWT was conducted based on a trial-and-error approach. Subsequently, the Parameter ESTimation (PEST) algorithm was used as a non-linear estimator to obtain the optimal calibration83. The project setup and initial runs were carried out under steady-state (SS) conditions, in order to establish an initial condition for subsequent runs. In order to ensure SS conditions, the model was calibrated for September 2009 average groundwater levels. At this stage, the initial hydraulic conductivity values were calibrated in SS conditions using a trial-and-error approach, and then the model was prepared for the next implementation. As the distinct stresses, including discharge and recharge periods are primarily applied to the Mahabad aquifer on a seasonal time scale, a stress period of three months (one season) was assumed. Subsequently, the stress period was further divided into six-time steps, as suggested by Anderson and Woessner84, who indicate that the numerical solution is in satisfactory agreement with the analytical solution. After estimating the initial values of the hydrodynamic coefficients in order to reduce the difference between the simulated and observed water table, the model for the transient state was run by using time-varying data, such as water supply of operation wells, recharge, and the water table of the observation wells. The values of specific yield (Sy), hydraulic conductivity coefficient (K), and hydraulic conductivity of the riverbed and streams were calibrated automatically by inverse modeling using the PEST method in the GMS software. Further details on the input data, and calibration processes of the MODFLOW-NWT model can be found in Appendix 7 in the supplementary information file.

The calibration and validation of the total integrated SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model was accomplished through independent calibration and validation of the two models, followed by calibration and validation of the integrated SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model. The SWAT model was constructed and simulated in the Mahabad plain for a duration of 13 years from 2006 to 2018, considering the first three years as a warmup period, which is the time required to achieve a reasonable initial hydrological state. The total available period was partitioned into two intervals, namely six years (2009–2014) for calibration and four years (2015–2018) for validation. The MODFLOW-NWT calibration and validation periods were treated the same as those of the SWAT, namely six years (2009–2014) for calibration and four years (2015–2018) for validation. No additional work in the determination of the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT parameters in the validation period was done because they were estimated in the SWAT and MODFLOW-NWT models calibration process. More details of the required input data used for the construction and calibration of the SWAT, MODFLOW-NWT, and the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model are described in the supplementary information file.

SWAT–MODFLOW-NWT linkage and application

The detailed linkages for the linkages in the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model can be found in the study of Bailey et al.8 and are summarized as a flowchart in Fig. 8. The SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model for the study region uses both the calibrated SWAT model and the calibrated MODFLOW-NWT model. In order to link these two models, the surface water and subsurface water flow components are exchanged between the Disaggregated Hydrological Response Units (DHRUs) of SWAT and the MODFLOW-NWT grid cells. The basic procedure of linking the two models is processed using ArcGIS. Both disaggregated HRUs (DHRUs) and SWAT stream networks intersect with the MODFLOW-NWT grid in order provide the necessary data for the linking files. In this study, a total of 40121 DHRUs were generated. The model was run for the 2009–2018 time period. The calibration and validation of the integrated SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model were divided into two distinct intervals, namely 6 years (2009–2014) for calibration and 4 years (2015–2018) for validation. The SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model is calibrated through a combination of automated and manual procedures. The automatic parameter estimation is carried out using SWAT-CUP 2012 using the Sequential Uncertainty Fitting Algorithm (SUFI2)41. Following model coupling, the SWAT groundwater module is replaced with the MODFLOW-NWT. Consequently, the groundwater parameters of SWAT model were excluded from the automatic calibration of SWAT-CUP. Figure 8 illustrates the major steps in the daily loop of the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT code and the most important steps of the coupled model.

No additional work in the determination of the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT parameters in the RIV package (Cond—riverbed hydraulic conductance) and the UPW package (i.e., Sy—specific yield, Ss—specific storage) was done because they were estimated in the MODFLOW-NWT model calibration process. Since hydraulic conductivity was calibrated in MODFLOW-NWT development, it was not included in the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT calibration process. Monthly streamflow, groundwater level, evapotranspiration, and crop yield were compared to the SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model. The monthly streamflow simulated was compared to the measured streamflow from the West-Azarbaijan Regional Water Authority along the Mahabad River (Gerdyaghoub gauge). A time-series comparison was used to compare the monthly groundwater level with the observed level for the 22 wells.

Applied scenarios

The coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model was to manage surface water and groundwater resources based on different schemes of water supply in the plain for different years. In general, the objective of this study was to examine the variable design of combined withdrawals of surface water and groundwater to supply the irrigation requirements of the major crops using a coupled model. This was done by determining the maximum safe extraction of groundwater for irrigation requirements across various zones and hydrological years, while maintaining a long-term relative groundwater sustainability without any negative impact on the flow of rivers in different areas of the study area. The overall objective was to decrease the share of irrigation requirement supply from surface water resources while simultaneously increase the share of inflow to Urmia Lake.

The main challenge was to locate the regions with a higher potential for the withdrawal of groundwater to supply the irrigation water. The sub-basins located at the aquifer level were divided into two zones based on the contour lines of the water table (See Fig. 9). The examination of the contour lines of the water table indicated that the central and northern regions (red areas) possess a higher potential for groundwater withdrawal due to the high water table (ranging from 1.5 to 3 m). However, the depth of groundwater in the eastern and southeastern regions of the aquifer is observed to be between 4 and 9 m (represented by white areas). Hence, the share of irrigation water supply from both surface water and groundwater was modified at 177.80 km2 (red areas), and remained constant the same in the 75.2 km2 (represented by white areas) of the aquifer, as depicted in Fig. 9.

The share of irrigation water supply in the red regions was changed as compared to the current conditions. In the current conditions, the supply of irrigation water is on average 61% from surface water and 39% from groundwater. The total water withdrawal from both surface water and groundwater sources remains constant and is determined based on the current agricultural water demand. In the design scenarios, irrigation water allocation was reduced by 10, 20, and 30 percent in surface water, while the same amount of groundwater was increased to preserve the total allocation. A literature review of studies also supports such this approach and the percentage of shifts53,86,87.

The adopted scenarios lead to a reduction in the share of evaporation as a non-beneficial consumption in the central and northern regions with high water tables. However, there is a limitation to the increased withdrawal from the groundwater in the zones of the river due to the possibility of developing a reverse hydraulic slope between surface water and groundwater sources, resulting in leakage from the river to the aquifer. In the following, the withdrawal management was also done within the river zone. It is expected that this management will lead to the prevention of river leakage to ground water, resulting in the intensification of the flow of the rivers to Urmia Lake. Therefore, the surface water supply will decrease by increasing the supply of groundwater in areas with the high water table. If this result leads to less demand for surface water supply, the share of releases to the lake will increase. After applying the scenarios, the indicators of the groundwater sustainability were examined to assess the significance of the drop in the water table in altering the storage capacity of the aquifer. The resulting changes also in the hydrograph of the water table, especially in the piezometers located in the northern and central piezometers of the study area, and the river flow at the Gerdyaghoub station were examined for confirmation.

Groundwater sustainability indicators

A set of indicators was used to evaluate the sustainability of groundwater based on of the proposed scenarios. Each of the proposed indicators emphasizes a specific aspect of the groundwater system based on both quantitative and qualitative data. Using indicators, as a standard, can provide effective and expected information for planners, managers, and policymakers. In this study, Groundwater Dependence (DG), Groundwater Development (GD), Groundwater Decay Rate (GDR), Aquifer Sustainability (AS), and Aquifer Recovery Potential (ARP) indices were used. The index of DG shows the importance of groundwater in relation to all water resources at the level of the study area88. The GD index shows the potential and ability to develop groundwater in each region. In the long-term planning of the exploitation of groundwater in the region, there is a need for an index that can evaluate the level of trust in the long-term exploitation of the aquifer. Therefore, to achieve this goal, the groundwater decay (GDR) rate index has been defined, which specifies the number of years that the aquifer can be relied upon88. The Aquifer Sustainability (AS) index indicates the sustainability of the aquifer according to the hydraulic and structural properties of the groundwater system. This index is very useful for policymaking due to its simplicity and national and regional scale. To calculate AS, it is necessary to obtain the total discharge and total recharge of the aquifer. The Aquifer Recovery Potential (ARP) index means the ability to recover and return to the normal condition of the aquifer according to the hydraulic and structural properties of the aquifer88. The description and equation of groundwater sustainability indicators are presented in Table 6.

Conclusion

Surface water and groundwater resources are often used in combination in the agriculture sector. They interact on different spatial or temporal scales within a plain, such as the Lake Urmia basin. Lake Urmia has gone through a devastating and rapid drying process over the past two decades. The current state of the lake is a result of a series of human and natural factors. Recently, the restoration of Lake Urmia has been a national priority. The lower water flow of rivers due to more occurring droughts, in addition to overexploitation of upstream water resources, has resulted in a significant reduction in the ecological share of water flow into Lake Urmia. In order to achieve sustainable use of water resources, especially in conditions of water scarcity, it is essential to have a tool that can consider all the processes in surface and subsurface systems. A comprehensive model is a practical tool that can simulate agricultural water supply in areas where water resources are used conjunctively of surface water and groundwater resources. Many studies have demonstrated that the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model can serve as a useful tool for evaluating the various withdrawal strategies on the water balance components.

The main objective of this study was to assess the simulation of surface water and groundwater components by using a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model under multi-purpose calibration of surface runoff, evapotranspiration, crop yield, and groundwater table in the Mahabad plain located within the Urmia Lake basin. The coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model was used as a comprehensive and integrated model to evaluate alternative irrigation water allocation schemes on the water balance components, namely water table and water inflow to the lake. The practical outcome of this study was to examine various predefined patterns of combined surface water and groundwater allocation to supply the irrigation requirements of regional crops by using the coupled model. This was done by determining the maximum safe extraction of groundwater in different zones and hydrological years, while maintaining a relatively sustainable groundwater balance without any negative impact on the flow of rivers in different areas of the plain.

The results indicated that the coupled model was well capable of simulating the fluctuations in the flow rate of the Mahabad river and water table in calibration and validation periods. The results also indicated that the new approach of using remote sensing ETa and crop yields gave excellent results. After the adoption of the coupled surface and groundwater SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model, a series of scenarios were examined to increase the share of groundwater to supply irrigation water and to examine their impact on the surface water release to the lake. The results demonstrated that the aquifer had a higher extraction capacity of the aquifer in the northern and central areas due to the relatively high-water table (1 to 3 m). Furthermore, an additional advantage of lowering the water table could translate into a reduction in direct evaporation loss from groundwater, improved soil quality, better aeration in the root zone area, and facilitated machinery operation by maintaining proper groundwater level (in sustainable conditions).

An increased share of groundwater irrigation supply would lead to a lower abstraction from surface water, which would ultimately increase the release of water to Urmia Lake. However, the results of long-term simulation studies showed that the water table would drop by about 0.25 m to 0.95 m after a 30% increase in groundwater for 10 consecutive years compared to the existing conditions. Excessive withdrawal of groundwater in the long term can lead to an increased drop in the water table, which may ultimately lead to unsustainable water resources in this region. After applying the scenarios, an analysis of the groundwater sustainability indicators in the current situation and after applying the scenarios indicated that a 30% increase in irrigation supply from groundwater and a 30% decrease from surface water (scenario 3) is still considered a suitable scenario. It should be noted that the analysis was based only on reallocation scenarios. Other management practical schemes, such as modification of the cropping pattern, reduced scale of irrigated areas, and other irrigation management plans, using the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model, can further augment the objectives of this study toward the restoration of Lake Urmia. It is also recommended that the pattern of optimal use of surface water and groundwater resources be evaluated by linking the coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model with an optimization algorithm or artificial intelligence in the future researches.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Bejranonda, W., Koontanakulvong, S., & Koch, M. Surface and groundwater dynamic interactions in the Upper Great Chao Phraya Plain of Thailand: Semi-coupling of SWAT and MODFLOW. Groundwater and Ecosystems, IAH Selected Papers on Hydrogeology. IAH, Goring, UK. 17, 17–21 (2007).

Dowlatabadi, S. & Ali Zomorodian, S. M. Conjunctive simulation of surface water and groundwater using SWAT and MODFLOW in Firoozabad watershed. KSCE J. Civil Eng. 20(1), 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-015-0354-8 (2016).

Wei, X., Bailey, R. T., Records, R. M., Wible, T. C. & Arabi, M. Comprehensive simulation of nitrate transport in coupled surface-subsurface hydrologic systems using the linked SWAT-MODFLOW-RT3D model. Environ. Model. Softw. 122, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2018.06.012 (2018).

Mosase, E., Ahiablame, L., Park, S. & Bailey, R. Modelling potential groundwater recharge in the Limpopo River Basin with SWAT-MODFLOW. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 9, 100260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2019.100260 (2019).

Wei, X. & Bailey, R. T. Assessment of system responses in intensively irrigated stream–aquifer systems using SWAT-MODFLOW. Water 11(8), 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11081576 (2019).

Sophocleous, M. A. et al. Integrated numerical modeling for basin wide water management: The case of the Rattlesnake Creek basin in South Central Kansas. J. Hydrol. 214(1–4), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00289-3 (1999).

Kim, N. W., Chung, I. M., Won, Y. S. & Arnold, J. G. Development and application of the integrated SWAT–MODFLOW model. J. Hydrol. 356(1–2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.02.024 (2008).

Bailey, R. T., Wible, T. C., Arabi, M., Records, R. M. & Ditty, J. Assessing regional-scale spatio-temporal patterns of groundwater–surface water interactions using a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model. Hydrol. Process. 30(23), 4420–4433. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10933 (2016).

Le Maitre, D. C. & Colvin, C. A. Assessment of the contribution of groundwater discharges to rivers using monthly flow statistics and flow seasonality. Water SA 34(5), 549–564. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v34i5.180652 (2008).

Chu, J., Zhang, C., & Zhou, H. Study on interface and frame structure of SWAT and MODFLOW models coupling. In Egu General Assembly Conference Abstracts 4559 (2010).

Aliyari, F. et al. Coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model for large-scale mixed agro-urban river basins. Environ. Model. Softw. 115, 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.02.014 (2019).

Sophocleous, M. A. & Perkins, S. P. Methodology and application of combined watershed and ground water models in Kansas. Hydrogeol. J. 236(3–4), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(00)00293-6 (2000).

Chunn, D., Faramarzi, M., Smerdon, B. & Alessi, D. S. Application of an integrated SWAT–MODFLOW model to evaluate potential impacts of climate change and water withdrawals on groundwater–surface water interactions in West-Central Alberta. Water 11(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11010110 (2019).

Sophocleous, M. A. Groundwater recharge and sustainability in the High Plains aquifer in Kansas, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 13(2), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-004-0385-6 (2005).

McDonald, M. G. & Harbaugh, A. W. A modular three-dimensional finite-difference ground-water flow model. Open-File Rep. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr83875 (1984).

Barazzuoli, P., Nocchi, M., Rigati, R. & Salleolini, M. A conceptual and numerical model for groundwater management: A case study on a coastal aquifer in southern Tuscany, Italy. Hydrogeol. J. 8(16), 1557–1576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-008-0324-z (2008).

Sibanda, T., Nonner, J. C. & Uhlenbrook, S. Comparison of groundwater recharge estimation methods for the semi-arid Nyamandhlovu area, Zimbabwe. Hydrogeol. J. 17, 1427–1441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0445-z (2009).

Niswonger, R. G., Panday, S, & Ibaraki, M. MODFLOW-NWT, A Newton formulation for MODFLOW-2005: USGS Survey Techniques and Methods 6-A37. https://doi.org/10.3133/tm6a37 (2011).

Bedekar, V., Niswonger, R. G., Kipp, K., Panday, S. & Tonkin, M. Approaches to the simulation of unconfined flow and perched groundwater flow in MODFLOW. Groundwater 50(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2011.00829.x (2012).

Scanlon, B. et al. Global synthesis of groundwater recharge in semiarid and arid regions. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 20(15), 3335–3370. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6335 (2006).

Raja, O., Parsinejad, M. & Tajrishy, M. Estimation and evaluation of water balance components by calibrated SWAT model, case study: Mahabad Plain. Watershed Eng. Manag. 15(1), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.22092/ijwmse.2022.357631.1957.(InPersian) (2023).

Nair, S. S., King, K. W., Witter, J. D., Sohngen, B. L. & Fausey, N. R. Importance of crop yield in calibrating watershed water quality simulation tools 1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 47(6), 1285–1297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2011.00570.x (2011).

Raja, O., Parsinejad, M. & Tajrishi, M. Simulation of groundwater balance using integrated surface and groundwater SWAT-MODFLOW-NWT model (Case Study: Mahabad Plain). J. Water Soil 36(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.22067/jsw.2022.74890.1138.(InPersian) (2022).

Izady, A. et al. Application of “panel-data” modeling to predict groundwater levels in the Neishaboor Plain, Iran. Hydrogeol. J. 20(3), 435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-011-0814-2 (2012).

Ehtiat, M., Jamshid Mousavi, S. & Srinivasan, R. Groundwater modeling under variable operating conditions using SWAT, MODFLOW and MT3DMS: A catchment scale approach to water resources management. Water Resour. Manag. 32, 1631–1649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-017-1895-z (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Quantifying the streamflow response to groundwater abstractions for irrigation or drinking water at catchment scale using SWAT and SWAT–MODFLOW. Environ. Sci. Europe 32, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00395-6 (2020).

Salmani, H. et al. Compilation simulation of surface water and groundwater resources using the SWAT-MODFLOW model for a karstic basin in Iran. Hydrogeol. J. 31(3), 571–587 (2023).

Aslam, R. A. et al. Integrated SWAT-MODFLOW modeling-based groundwater adaptation policy guidelines for lahore, Pakistan under projected climate change, and human development scenarios. Atmosphere 13(12), 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13122001 (2001).

Correa-González, A., Hernández-Bedolla, J., Martínez-Cinco, M. A., Sánchez-Quispe, S. T. & Hernández-Hernández, M. A. Assessment of nitrate in groundwater from diffuse sources considering spatiotemporal patterns of hydrological systems using a coupled SWAT/MODFLOW/MT3DMS model. Hydrology 10(11), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology10110209 (2023).

Shaabani, M. K., Abedi-Koupai, J., Eslamian, S. S. & Gohari, S. A. R. Simulation of the effects of climate change, crop pattern change, and developing irrigation systems on the groundwater resources by SWAT, WEAP and MODFLOW models: A case study of Fars province, Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26(4), 10485–10511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03157-5 (2024).

Doble, R., Pickett, T., Crosbie, R. & Morgan, L. A new approach for modelling groundwater recharge in the South East of South Australia using MODFLOW. Goyder Inst. Water Res. Tech. Rep. 15, 26 (2015).

Ware, H. H., Mengistu, T. D., Yifru, B. A., Chang, S. W. & Chung, I. M. Assessment of spatiotemporal groundwater recharge distribution using SWAT-MODFLOW model and transient water table fluctuation method. Water 15(11), 2112. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15112112 (2023).

Liang, F. et al. The development of a coupled soil water assessment tool-MODFLOW model for studying the impact of irrigation on a regional water cycle. Water 15(20), 3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15203542 (2023).

Yifru, B. A. et al. Estimating exploitable groundwater for agricultural use under environmental flow constraints using an integrated SWAT-MODFLOW model. Agric. Water Manag. 303, 109024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2024.109024 (2024).

Taie Semiromi, M. & Koch, M. Analysis of spatio-temporal variability of surface–groundwater interactions in the Gharehsoo river basin, Iran, using a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW model. Environ. Earth Sci. 78(6), 201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8206-3 (2019).

Sisay, B. M., Nedaw, D., Birhanu, B. & Gigar, A. G. Application of SWAT and MODFLOW models for characterization of surface–groundwater interaction in the Modjo River catchment, central Ethiopia. Environ. Earth Sci. 82(13), 34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-10988-y (2023).

Shaabani, M. K., Abedi-Koupai, J., Eslamian, S. S. & Gohari, A. Simulation of the effects of climate change and reduce irrigation requirements on groundwater recharge using SWAT and MODFLOW models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9(2), 1681–1693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01580-7 (2023).

Hamdi, M. & Kalifa, G. Analysis of groundwater depletion in the Saskatchewan river basin in Canada from coupled SWAT-MODFLOW and satellite gravimetry. Hydrology 10(9), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology10090188 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Identification of surface water-groundwater nitrate governing factors in Jianghuai hilly area based on coupled SWAT-MODFLOW-RT3D modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168830 (2024).

Yang, X., Dai, C., Liu, G., Meng, X. & Li, C. Evaluation of groundwater resources in the middle and lower reaches of Songhua River based on SWAT model. Water 16(19), 2839. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16192839 (2024).

Abbaspour, K. et al. A continental-scale hydrology and water quality model for Europe: Calibration and uncertainty of a high-resolution large-scale SWAT model. J. Hydrol. 524, 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.03.027 (2015).

Abbaspour, K. et al. Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. J. Hydrol. 333(2), 4413–4430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.09.014 (2007).

Eini, M. R., Javadi, S., Delavar, M., Gassman, P. W. & Jarihani, B. Development of alternative SWAT-based models for simulating water budget components and streamflow for a karstic-influenced watershed. Catena 195, 104801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104801 (2020).

Akoko, G., Le, T. H., Gomi, T. & Kato, T. A review of SWAT model application in Africa. Water. 13(9), 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13091313 (2021).

Busico, G. et al. Evaluating SWAT model performance, considering different soils data input, to quantify actual and future runoff susceptibility in a highly urbanized basin. J. Environ. Manag. 266, 110625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110625 (2020).

Tan, M. L. & Yang, X. Effect of rainfall station density, distribution and missing values on SWAT outputs in tropical region. J. Hydrol. 584, 124660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.124660 (2020).

Raja, O., Parsinejad, M. & Tajrishi, M. Multipurpose calibration of SWAT model in estimating runoff, evapotranspiration, and crop yield (A Case Study: Mahabad Plain). Iran-Water Resour. Res. 17(4), 11–34 (2022) ((In Persian)).

Wheater, H. S. Hydrological processes, groundwater recharge and surface-water/groundwater interactions in arid and semi-arid areas. In Groundwater Modeling in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas, 1st ed., 5–37. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Yin, L. et al. Groundwater-recharge estimation in the Ordos Plateau, China: Comparison of methods. Hydrogeol. J. 8(19), 1563–1575 (2011).

Samimi, M. et al. Modeling arid/semi-arid irrigated agricultural watersheds with SWAT: Applications, challenges, and solution strategies. J. Hydrol. 590, 125418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125418 (2020).

Taheri Tizro, A. & Kamali, M. Groundwater modeling by MODFLOW model in Toyerkan aquifer and evaluation of hydrogeological state under present and future conditions. Water Eng. 12(40), 89–104 (2019) ((In Persian)).

Hamraz, B. S., Akbarpour, A. & Pourreza Bilondi, M. Assessment of parameter uncertainty of MODFLOW model using GLUE method (Case study: Birjand plain). Water Soil Conserv. 22(6), 61–79 (2016) ((In Persian)).

Koohestani, N., Halaghi, M. M. & Dehghani, A. Numerical simulation of groundwater level using MODFLOW software (a case study: Narmab watershed, Golestan province). Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 1(8), 858–873 (2013).

Moriasi, D. N. et al. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 50(3), 885–900. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.23153 (2007).

Barlow, P. M. & Leake, S. A. Streamflow depletion by wells: Understanding and managing the effects of groundwater pumping on streamflow (Vol. 1376). (US Geological Survey, 2012). https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1376

Xu, R. et al. Quantifying climate and anthropogenic impacts on runoff using the SWAT model, a Budyko-based approach and empirical methods. Hydrol. Sci. J. 68(10), 1358–2137. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2023.2218551 (2023).

Abbaspour, K.C. SWAT-CUP, SWAT Calibration and uncertainty programs, version 2 (user manual), EAWAG, 105 (2009).

Boufala, M. H. et al. Assessment of the best management practices under a semi-arid basin using SWAT model (case of M’dez watershed, Morocco).. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-021-01123-6 (2022).

Aboelnour, M., Gitau, M. W. & Engel, B. A. A comparison of streamflow and baseflow responses to land-use change and the variation in climate parameters using SWAT. Water 12(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010191 (2020).

Kim, J. T., Lee, C. H. & Lee, N. Improvement and analysis for accuracy of baseflow using SWAT-CUP premium in the Yongjeon Stream, South Korea. Pure Appl. Geophys. 181(1), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-023-03381-0 (2024).

Maidment, F. Human resources. Horizons (1992).

Bastiaanssen, W. G. M., Cheema, M. J. M., Immerzeel, W. W., Miltenburg, I. J. & Pelgrum, H. J. W. R. R. Surface energy balance and actual evapotranspiration of the transboundary Indus Basin estimated from satellite measurements and the ETLook model. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011wr010482 (2012).

Bennour, A. et al. Calibration and validation of SWAT model by using hydrological remote sensing observables in the Lake Chad Basin. Remote Sens. 14(6), 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14061511 (2022).

Herman, M. R., Hernandez-Suarez, J. S., Nejadhashemi, A. P., Kropp, I. & Sadeghi, A. M. Evaluation of multi-and many-objective optimization techniques to improve the performance of a hydrologic model using evapotranspiration remote-sensing data. J. Hydrol. Eng. 25(4), 04020006. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001896 (2020).

Alizadeh, A. et al. Estimation of actual evapotranspiration at the basin year scale using SWAT. Iran. J. Irrig. Drain. 2(7), 258–2437. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijswr.2020.300306.668567.(InPersian) (2013).

Ahmadzadeh, H., Morid, S. & Delavar, M. Assessment of changes in agricultural crop yields and inflows to Lake Urmia in Zarrinehrud River basin due to changing irrigation systems from surface to pressurized using the SWAT model. Iran. J. Irrig. Drain. 8(1), 1–15 (2014) ((In Persian)).

Yan, B., Fang, N. F., Zhang, P. C. & Shi, Z. H. Impacts of land use change on watershed streamflow and sediment yield: An assessment using hydrologic modelling and partial least squares regression. J. Hydrol. 484, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.01.008 (2013).

Gao, Y. & Long, D. Intercomparison of remote sensing-based models for estimation of evapotranspiration and accuracy assessment based on SWAT. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 22(25), 4850–4869. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7104 (2008).

Ningthoujam, V. & Ngangbam, R. SWAT model calibration and validation with remotely sensed evapotranspiration data in Maklang-Tuyungbi-Taret lok Ungauged Basin in Manipur India. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01454-1 (2024).

Musyoka, F. K., Strauss, P., Zhao, G., Srinivasan, R. & Klik, A. Multi-step calibration approach for SWAT model using soil moisture and crop yields in a small agricultural catchment. Water 13(16), 2238. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13162238 (2021).

Jafari, T., Kiem, A. S., Javadi, S., Nakamura, T. & Nishida, K. Fully integrated numerical simulation of surface water-groundwater interactions using SWAT-MODFLOW with an improved calibration tool. Journal of Hydrology. Regional Studies 35, 100822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2021.100822 (2021).

Molina-Navarro, E. et al. Comparison of abstraction scenarios simulated by SWAT and SWAT-MODFLOW. Hydrol. Sci. J. 64(4), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2019.1590583 (2019).

Gao, F. et al. Assessment of surface water resources in the big sunflower river watershed using coupled SWAT–MODFLOW model. Water 11(3), 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030528 (2019).

Park, S. & Bailey, R.T. SWAT-MODFLOW tutorial—Documentation for preparing model simulations. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA; 56 (2017).

Water Consulting Engineers and Sustainable Development. Update studies of water resources balance study areas of Urmia Lake catchment area leading to the water year of 2009–2010, Mahabad study area water balance report, 81 (2014). (In Persian)

Xu, Y. & Beekman, H. E. Review: Groundwater recharge estimation in arid and semi-arid southern Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 27(3), 929–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-018-1898-8 (2018).

Singh, A. P. & Prashant, B. Development of groundwater sustainability index: A case study of western arid region of Rajasthan, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23(2), 1844–1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00654-9 (2021).

Guzman, A. et al. A model integration framework for linking SWAT and MODFLOW. Environ. Model. Softw. 73, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.08.011 (2015).

Lehner, B., Verdin, K. & Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 89(10), 93–94. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008eo100001 (2008).

Water Engineering Research Institute. Collaborative land cover mapping of the Lake Urmia Basin, Iran. Tarbiat Modares University, GCP/IRA/066/JPN-18-003, 61 pp (2019).

Sedighi Hamidi, P. Investigating the effect of expansion of pressurized irrigation systems on water resources of Urmia Lake basin (Mahabad sub-basin), M.Sc. thesis, Urmia university, 131 (2018) (In Persian)

Ledger, D. C., Davis, S. N. & de Wiest, R. J. M. Hydrogeology. Geograp. J. 133(3), 391. https://doi.org/10.2307/1793590 (1967).

Gallagher, M. & Doherty, J. Parameter estimation and uncertainty analysis for a watershed model. Environ. Model. Softw. 22(7), 1000–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2006.06.007 (2007).

Woessner, W. W. & Anderson, M. P. The hydro-malaprop and the ground water table (Technical Commentary). Ground Water 40(5), 465–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2002.tb02529.x (2002).

Valizadegan, E. & Yazdanpanah, S. Quantitative model of optimal conjunctive use of Mahabad plain’s surface and underground water resources. Amirkabir J. Civ. Eng. 50(4), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.22060/ceej.2017.12739.5266(InPersian) (2018).

Amiri, F. et al. Prediction of groundwater level fluctuations in steady and unsteady state conditions using PMWIN in Rayen Aquifer, Iran. Desalin. Water Treat. 151, 414–424. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2019.24099 (2019).

Arumugam, K., Karthika, T., Elangovan, K., Sangeetha, R. K. & Vikashini, S. Groundwater modelling using visual modflow in Tirupur Region, Tamilnadu, India. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 19(4), 1423–1433. https://doi.org/10.46488/nept.2020.v19i04.008 (2020).

Vrba, J. et al. Groundwater resources sustainability indicators 114. A. Lipponen (Ed.). Paris: UNESCO. (2007)

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Agricultural Organization of West Azarbaijan, Regional Water Company of West Azarbaijan, and Urmia Lake Restoration Plan (ULRP) that provided access to data required for the preparation of this article.

Funding