Abstract

This study modeled the impact of anthropogenic heat (AH) on urban climates, focusing on Sydney during 2017’s heightened temperatures. The motivation behind this study stems from the increasing significance of understanding urban heat dynamics as cities globally grapple with regional climate change, necessitating targeted strategies for effective climate resilience cities. By investigating how varying levels of AH influence local urban climate conditions, this study addresses a critical gap in current urban climate study, particularly in the context of Sydney, an area that has not yet been extensively explored. Utilizing the weather research and forecasting (WRF) model coupled with building effect parameterization (BEP) and building energy model (BEM), i.e., the WRF/BEP + BEM model, four AH release scenarios were analyzed. Higher AH levels, especially at 14:00 LT, exhibited significant peaks: 266.5 W m−2 for sensible heat and 35.3 W m−2 for latent heat compared to the control scenario. This increase corresponded to a notable rise in ambient temperatures by 2.1 °C, with surface temperatures surging by 8.1 °C. Wind speeds notably increased by 4.6 m s−1 during higher AH release periods, affecting city airflow patterns. Moreover, elevated AH levels amplified the convective planetary boundary layer (PBL) height by 2013.7 m at 14:00 LT, potentially impacting pollutant dispersion and atmospheric quality. Notably, heightened AH profiles intensified sea breeze circulations, particularly impacting densely populated urban areas. These findings demonstrate a direct link between AH, exacerbated local urban warming, altered boundary layer dynamics, and intensified sea breeze circulations. This study emphasizes the urgent need to comprehend and manage AH for sustainable urban development and effective climate resilience strategies in Sydney and similar urban environments. By shedding light on these relationships, this study aims to contribute to the formulation of policies that mitigate urban overheating and enhance the livability of urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The urban environment is increasingly becoming a focal point for various human activities and a hub of socioeconomic development1. This growth leads to alterations in the local climate2, with anthropogenic heating (AH) emerging as a significant factor in this shift. Understanding the complex relationship between urbanization, AH, and their collective impact on climate, particularly during heatwaves, is crucial to address the challenges posed by climate change3. AH, stemming from human activities such as industrial processes, transportation, and energy usage, significantly alters the thermal balance within urban regions4. This surplus heat can lead to localized temperature variations, commonly known as the urban heat island (UHI) effect, wherein urban areas experience higher temperatures compared to their rural surroundings5. The implications of increased AH become particularly pronounced during heatwaves, which are characterized by prolonged periods of excessively high temperatures. Urban planners, policymakers, and researchers must collaborate closely to understand this phenomenon, considering factors such as land use changes, building materials, energy use patterns, and AH source distribution, all crucial in shaping the UHI effect6,7. The consequences of climate change extend beyond mere temperature changes, encompassing alterations in precipitation patterns, air quality degradation, and the overall microclimatic conditions experienced by urban residents8. Increased AH during heatwaves raises health risks, including heat-related illnesses and mortality, as well as increased energy demand for cooling, thus exacerbating the vulnerability of urban populations, particularly those in disadvantaged communities9.

Despite these complexities, technological advances and analytical methods offer promising ways to assess AH’s influence on urban climate during heatwaves10. High-resolution satellite data, sophisticated climate models, and advanced sensors aid researchers in quantifying, simulating, and predicting the UHI effect and its impacts during extreme heat events11. However, the study of AH and its impact on urban climates, especially during heatwaves, is underrepresented in scientific research12. There is a significant scarcity of studies specifically addressing the detailed ramifications of AH, despite its profound impact on local temperatures, energy dynamics, and atmospheric processes13. Few studies have investigated the complex relationship between human-induced heat and urban meteorology at a city scale, particularly in diverse urban landscapes like Sydney14. This scarcity emphasizes the urgent need for more extensive investigations into AH effects during heatwaves, highlighting the rarity of studies examining its complex implications on urban environments. The study of AH in Sydney is critical due to its significant implications for urban climate dynamics during heatwaves, public health, and energy systems. Sydney, like many global cities, is experiencing increasingly frequent and severe heatwaves as a result of climate change. AH—resulting from human activities such as building energy consumption, transportation, and industrial processes—exacerbates the UHI effect, leading to elevated localized temperatures during heat events. This intensification of heat contributes to rising health risks, including heat-related illnesses and mortality, increased energy demand for cooling, and a general decline in urban livability, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. Despite the well-recognized role of AH in urban heat dynamics, there is a notable lack of comprehensive, city-wide data quantifying AH in Sydney, particularly during heatwaves. This absence of detailed information limits the accuracy of predictive models and constrains the development of effective urban planning and policy interventions. To address this gap, our study hypothesizes the potential impacts of AH at the city scale, utilizing existing data from similar urban environments and integrating it with advanced modeling techniques. This approach allows us to estimate AH’s contribution to urban overheating during heatwaves and identify its spatial variability, particularly in densely populated and industrial areas.

The current state of study on AH in urban areas encompasses a multifaceted understanding of its sources, effects, and mitigation strategies. Advanced measurement techniques, including remote sensing and modeling approaches such as computational fluid dynamics, aid in quantifying and predicting the spatial distribution of AH within cities15. Recent studies indicate that AH significantly contributes to urban heat, with estimates suggesting it can raise local temperatures by 1–3 °C or more in densely populated areas during heatwaves16. Buildings are responsible for approximately 50–60% of this heat, particularly from air conditioning, heating systems, and electronic devices17. Transportation, including vehicle emissions and road surfaces, accounts for around 20–30%18, while industrial activities contribute approximately 10–20%19. Advanced modeling techniques, such as computational fluid dynamics and energy balance models, have improved estimates of AH distribution, revealing localized hotspots within cities20. Mitigation strategies, including the incorporation of green infrastructure and energy-efficient building designs, have shown potential to reduce AH emissions by up to 30% in certain urban zones21. Ongoing interdisciplinary study and technological advancements are refining understanding and aiding in the development of targeted solutions for managing AH in urban areas while addressing challenges in accurately quantifying and modeling the complex interplay of AH with urban microclimates, particularly during heatwaves, and integrating AH considerations into broader climate change mitigation efforts, ensuring equitable urban development22.

This study fills the study gap by evaluating how increased AH affects various aspects of Sydney’s urban climate dynamics during heatwaves, including meteorological parameters, energy fluxes, boundary layer dynamics, and sea breeze circulations. Sophisticated modeling systems, the weather research and forecasting (WRF) model coupled with building effect parameterization (BEP) and building energy model (BEM), i.e., the WRF/BEP + BEM model, simulated different AH emission scenarios across Sydney’s urban landscape, representing controlled increases in human-generated heat emissions across low, medium, and high-density urban settings. The study also explores the intricate relationship between AH profiles and boundary layer dynamics, notably affecting the convective planetary boundary layer (PBL) height and potentially influencing air quality, pollutant dispersion, and atmospheric dynamics in urban environments during heatwaves. Additionally, it investigates AH’s influence on sea breeze circulations, highlighting its impact on wind patterns and local climatic conditions.

The insights gained from the outcomes of this study can contribute significantly to understanding the multifaceted impacts of increased AH on Sydney’s urban climate during heatwaves, informing effective urban planning, sustainable infrastructure design, and climate change mitigation measures for resilient urban environments. By filling this critical knowledge gap, our study enhances the understanding of AH’s influence on Sydney’s heat distribution during extreme heat events and provides a valuable framework for future studies in cities facing similar climatic and urbanization challenges. The findings offer actionable insights for urban planners and policymakers, enabling the design of targeted heat mitigation strategies, such as increasing urban green cover, implementing reflective surfaces, and optimizing building energy systems. Moreover, the results can directly inform Sydney’s climate adaptation policies, providing evidence-based strategies to mitigate the impacts of AH, improve energy efficiency, and bolster urban resilience against future heat events. This study has broader implications beyond Sydney, offering transferable methodologies and insights that can be applied to other cities globally. By addressing a significant gap in AH research, this study advances knowledge in urban climate resilience and provides a scientific basis for developing sustainable, heat-resilient urban environments. The study’s findings are crucial for shaping climate adaptation strategies and contribute to the growing body of research on urban overheating and the impacts of human-induced climate stressors.

Overview of the study area

The city is characterized by a temperate climate, with warm summers and mild winters, but recent decades have seen increasing temperature extremes, particularly in the summer months. Sydney has been identified as particularly vulnerable to urban heat intensification due to its rapid urbanization, expansive infrastructure, and reliance on energy-intensive activities, all of which contribute to AH emissions. Sydney’s urban morphology is highly diverse; encompassing densely populated central business districts (CBDs), sprawling residential suburbs, industrial zones, and green spaces. The high-density built-up areas, particularly the CBD and commercial districts, are characterized by a concentration of high-rise buildings, extensive transportation networks, and significant industrial activities. These factors contribute to increased AH emissions and intensify the UHI effect. Conversely, the city’s coastal areas and green spaces, such as parks and urban forests, serve as cooler zones, helping to mitigate some of the heat impacts. The city’s energy infrastructure also plays a key role in shaping its heat dynamics. Sydney relies heavily on electricity for cooling during extreme heat events, and the widespread use of air conditioning in commercial and residential buildings contributes to elevated levels of waste heat release. Industrial hubs, such as those in Western Sydney, are significant sources of AH due to high levels of manufacturing and transportation activity. These factors, combined with the city’s growing vehicle fleet and expanding infrastructure, make Sydney a hotspot for AH emissions. Sydney’s geography further contributes to its complex heat dynamics. The city is located on the coastal plain, with topographical features that include coastal cliffs, river systems (such as the Parramatta River), and hilly regions toward the west. These natural features, combined with prevailing wind patterns, influence the distribution and intensity of heat across different parts of the city. Western Sydney, for instance, tends to experience higher temperatures than coastal areas due to the lack of sea breezes and reduced vegetation cover. Another critical aspect of Sydney’s urban heat challenge is its ongoing urban sprawl. The city has expanded westward in recent years, leading to increased impervious surfaces such as roads, buildings, and parking lots, which absorb and retain heat. This urban expansion, particularly in areas with limited green cover, exacerbates the UHI effect and heightens the contribution of AH from residential energy use, vehicular emissions, and industrial activities. The socio-economic composition of Sydney’s neighbourhoods also influences energy consumption patterns and the associated AH emissions. Wealthier areas, typically closer to the coast, have better access to green spaces and modern infrastructure, which can mitigate heat impacts. In contrast, lower-income neighbourhoods, particularly in Western Sydney, are more exposed to extreme heat due to higher concentrations of impervious surfaces, reduced tree cover, and limited access to cooling resources.

Results

Regional impacts of anthropogenic heat on urban energy balance

The WRF/BEP + BEM model effectively computed the sensible, latent, ground heat, and net inflow radiation fluxes originating from the urban surface (Table S2 and S3). At 14:00 LT, the maximum and average sensible heat flux (Qsensible) across the city are recorded at 761.8 W m−2 and 555.7 W m−2 for AH1, 819.1 W m−2 and 582.0 W m−2 for AH2, 870.4 W m−2 and 605.6 W m−2 for AH3, and 929.6 W m−2 and 632.8 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios, respectively (Fig. 1). By 18:00 LT, the average sensible heat flux measures 4.5.3 W m−2, 4.8 W m−2, 458.2 W m−2, and 486.3 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively. Notably, the maximum increase in sensible heat flux during 14:00 LT reaches 98.7 W m−2 for AH1, 155.9 W m−2 for AH2, 207.2 W m−2 for AH3, and 266.5 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios over areas encompassing the CBD and inner west. On average, during summer afternoons at 14:00 LT, the sensible heat flux experiences increase of 60.2 W m−2, 95.1 W m−2, 126.4 W m−2, and 162.5 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively, across the urban domain. At 18:00 LT, the maximum rise in sensible heat flux during summer months registers at 59.9 W m−2 for AH1, 98.2 W m−2 for AH2, 122 W m−2 for AH3, and 155 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios. On average, the increase in sensible heat flux during summer evenings at 18:00 LT measures 51 W m−2, 83.7 W m−2, 103.9 W m−2, and 132 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively. These results illustrate substantial variations in sensible heat flux due to differing AH scenarios, particularly accentuated during specific time frames throughout the day across the urban domain.

The map illustrates the rise in average sensible heat flux at the peak hour (14:00 LT) for various scenarios: (a) AH1, (b) AH2, (c) AH3, and (d) AH4. It showcases the contrast between AH scenarios minus control within the same urban grid cell. The map was drawn by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (available at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources.

The maximum and average latent heat flux (Qlatent) observed across the city at 14:00 LT are recorded at 55 W m−2 and 42.2 W m−2 for AH1, 59 W m−2 and 45.3 W m−2 for AH2, 65.2 W m−2 and 50 W m−2 for AH3, and 70.7 W m−2 and 54.2 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios (Fig. 2). During the late afternoon at 18:00 LT, the average latent heat flux values stand at 12.5 W m−2, 15.7 W m−2, 19.2 W m−2, and 21.6 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively. In specific regions like the CBD and eastern Sydney, the maximum increase in latent heat flux during 14:00 LT reaches 15.3 W m−2 for AH1, 20.5 W m−2 for AH2, 28.3 W m−2 for AH3, and 35.3 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios. On average, during summer afternoons at 14:00 LT, the latent heat flux experiences rises of 10.2 W m−2, 13.7 W m−2, 18.9 W m−2, and 23.6 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively, over the urban domain. By 18:00 LT, both the maximum and average increase in latent heat flux during summer months stand at 4.1 W m−2 and 2.6 W m−2 for AH1, 9.2 W m−2 and 5.8 W m−2 for AH2, 14.7 W m−2 and 9.3 W m−2 for AH3, and 18.5 W m−2 and 11.7 W m−2 for AH4 scenarios specifically over eastern Sydney. At 06:00 LT, the maximum increase of latent heat flux registers at 4.3 W m−2, 6.9 W m−2, 11.6 W m−2, and 14.9 W m−2 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively, across the urban domain. These variations illustrate the alterations in latent heat flux across different scenarios and times of the day, emphasizing the influence of AH on these energy fluxes in urban areas.

The map illustrates the rise in average latent heat flux at the peak hour (14:00 LT) for various scenarios: (a) AH1, (b) AH2, (c) AH3, and (d) AH4. It showcases the contrast between AH scenarios minus control within the same urban grid cell. The map was drawn by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (available at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources.

Regional impacts of anthropogenic heat on standard meteorological fields

The WRF/BEP + BEM urban modeling system allows for the calculation of ambient and surface temperatures based on surface energy balance flux partitions (Table S4). Under the various AH scenarios—AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4—the ambient temperatures at 14:00 exhibit ranges between 22.9 °C and 43.4 °C for AH1, 23.1 °C to 43.7 °C for AH2, 23.5 °C to 44.0 °C for AH3, and 23.8 °C to 44.3 °C for AH4 (Fig. 3). During the early morning at 06:00 LT, these temperatures range from 16.1 °C to 27.9 °C for AH1, 16.3 °C to 28.1 °C for AH2, 16.5 °C to 28.2 °C for AH3, and 16.7 °C to 28.5 °C for AH4.The results underscore that elevating AH emissions on urban surfaces correlates with increased maximum peak ambient temperatures (Tambient) across CBD and eastern Sydney. Comparing to the control case, there’s a noticeable escalation in peak ambient temperatures—1.3 °C, 1.6 °C, 1.8 °C, and 2.1 °C for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4, respectively. On average, during summer afternoons at 14:00, there’s an ambient temperature increase of 0.6 °C for AH1, 0.9 °C for AH2, 1.3 °C for AH3, and 1.6 °C for AH4. By 18:00 LT, there is a maximum temperature surge of 1.2 °C, 1.4 °C, 1.7 °C, and 1.9 °C for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4, respectively, over eastern Sydney, with average increases ranging from 0.5 °C to 1.4 °C during summer months. These findings highlights a direct link between increased AH emissions and elevated ambient temperatures, particularly evident during peak daytime and late afternoon, impacting specific Sydney regions.

The map illustrates the rise in average ambient temperature at the peak hour (14:00 LT) for various scenarios: (a) AH1, (b) AH2, (c) AH3, and (d) AH4. It showcases the contrast between AH scenarios minus control within the same urban grid cell. The map was drawn by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (available at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources.

Under the AH emission scenarios, surface temperatures (Tsurface) at 14:00 LT range between 32.9 °C and 58.9 °C for AH1, 34.6 °C to 61.2 °C for AH2, 37.0 °C to 63.3 °C for AH3, and 39.3 °C to 65.6 °C for AH4 across the city (Fig. 4). During the early morning at 6:00 LT, these temperatures exhibit variations from 16.7 °C to 34.4 °C for AH1, 18.1 °C to 35.7 °C for AH2, 19.5 °C to 37.4 °C for AH3, and 21.3 °C to 38.9 °C for AH4. Notably, the maximum increase in surface temperature at 14:00 LT reaches 3.8 °C for AH1, 5.2 °C for AH2, 6.7 °C for AH3, and 8.0 °C for AH4 over regions in eastern Sydney and South Sydney. On average, the urban surface temperature experiences increase of 3.1 °C, 4.3 °C, 5.6 °C, and 6.9 °C for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4, respectively, during summer afternoons at 14:00 LT. By utilizing AH profiles across the urban landscape, the maximum rise in surface temperature at 18:00 LT stands at 3.2 °C for AH1, 4.6 °C for AH2, 6.0 °C for AH3, and 7.4 °C for AH4 scenarios. The average escalation in urban surface temperature at 18:00 LT during summer months demonstrates increases of 2.7 °C, 3.9 °C, 5.1 °C, and 6.3 °C for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios, respectively. These findings highlight significant temperature escalations tied directly to varying levels of AH emissions, particularly pronounced during late afternoons and early evenings across specific regions within Sydney.

The map illustrates the rise in average surface temperature at the peak hour (14:00 LT) for various scenarios: (a) AH1, (b) AH2, (c) AH3, and (d) AH4. It showcases the contrast between AH scenarios minus control within the same urban grid cell. The map was drawn by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (available at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources.

Under the base case simulation, the average wind speeds (Wspeed) at 06:00 LT, 14:00 LT, and 18:00 LT register at 8.8 m s−1, 9.4 m s−1, and 8.9 m s−1, respectively, across the city. Comparatively, in the scenarios with increased AH, notable changes in wind speeds are observed. During 14:00 LT, the maximum increase in wind speed compared to the control case measures 1.9 m s−1 for AH1, 2.8 m s−1 for AH2, 3.7 m s−1 for AH3, and 4.6 m s−1 for AH4 scenarios, particularly over areas such as the inner west, CBD, lower north shore, and the western part of CBD. Similarly, during 18:00 LT, the wind speed escalates by 1.4 m s−1, 2.1 m s−1, 2.9 m s−1, and 3.3 m s−1 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios respectively, over these regions. Over the entire summer period, the average wind speed during 14:00 LT increases by 1.5 m s−1, 2.3 m s−1, 3.1 m s−1, and 4.0 m s−1 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios respectively across the city (Fig. 5). At 06:00 LT, the average wind speed rises by 0.5 m s−1, 1.1 m s−1, 1.3 m s−1, and 1.8 m s−1 for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 scenarios respectively over the urban domain. These changes indicate the impact of AH on altering wind patterns and speeds throughout different times of the day, influencing the dynamics of urban airflow.

The map illustrates the rise in average wind speed at the peak hour (14:00 LT) for various scenarios: (a) AH1, (b) AH2, (c) AH3, and (d) AH4. It showcases the contrast between AH scenarios minus control within the same urban grid cell. The map was drawn by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (available at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources.

Regional impacts of anthropogenic heat on urban boundary layer

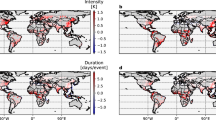

The variations in the PBL depth across different scenarios in the Sydney urban area compared to the control experiment demonstrate significant impacts linked to the coverage rate of various AH profiles. It is notable that the introduction of higher AH profiles, especially in the most aggressive scenario (AH4 experiments), leads to an increase in convective PBL height, with a maximum rise ranging approximately between 170 and 550 m. Examining the spatial distribution of this increase over the 59-day extreme heat period reveals heightened convective PBL depth across Sydney’s metropolitan areas. This indicates an enhanced potential for the lower atmosphere to efficiently disperse pollutants vertically, potentially influencing air quality. However, while there’s observed consistency in effects throughout simulation periods, Fig. 6 demonstrates complex and variable spatial gradients outside urban limits, often contingent on horizontal grid size. These structures seem to correlate with the simulation periods, yet a comprehensive validation necessitates further investigation, exceeding the scope of this study. The impact of high-density urban building environments on lower atmospheric dynamics from city to regional scales is evident. Diurnal variations in PBL, influenced by different AH profiles at the city scale, have been documented. The magnitude of PBL height increase notably escalates with higher AH profiles. Figure 6 details the spatial distribution of PBL height increase at 14:00 LT due to increased AH profiles, illustrating corresponding spatial shifts in vertical wind speed. Notably, the maximum PBL height increase during 14:00 LT spans 349.3 m, 865.6 m, 1362.5 m, and 2013.7 m for AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4respectively, with average values of 239.7 m, 594 m, 934.9 m, and 1381.8 m. At 18:00 LT, the maximum increase reaches 203.2 m for AH1, 523.3 m for AH2, 877 m for AH3, and 1225.1 m for AH4, predominantly affecting CBD, Inner West, Parramatta, and Southern Sydney during peak hours. Increased PBL depth primarily results from solar radiation absorbed by AH-induced aerosols, boosting sensible heat and turbulence in the lower atmosphere. Changes in AH profiles are expected to amplify urban-induced warming, intensifying convective mixing and thus raising PBL depth. This may help dilute air pollutants and disperse them across the city, impacting moisture transport and potentially influencing cloud formation and precipitation in urban and downwind areas.

The cross-sectional profile illustrates the impact of AH on sea breeze dynamics during the peak hour (14:00 LT) over Sydney, spanning from east (sea breeze) to west (inland) for different scenarios: (a) control scenario, (b) AH1, (c) AH2, (d) AH3, and (e) AH4. The specific humidity gradient in the vertical direction determines the static stability of the lower atmosphere. During high solar radiation periods, the convective boundary layer develops rapidly, and this development intensifies progressively with the impact of AH. This map was generated by the first author utilizing WRF-Python (accessible at https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and does not necessitate permissions from external sources. The black solid lines denote the height of PBL during peak hour.

Regional impacts of anthropogenic heat on sea breeze circulations

The amplification of sea breeze circulation is intricately tied to the overarching synoptic conditions, dictating near-surface winds. Vertically, the PBL height in Sydney exhibits a close correlation with the advection of the sea breeze. When increasing various AH profiles at the city scale (as depicted in Fig. 6), this augmentation could heighten the PBL, potentially spurring localized circulation within Sydney’s urban domain. Notably, results suggest a swift onset of the sea breeze by early afternoon (14:00 LT), attributed to the “regional low” effect amidst a higher PBL and offshore synoptic wind flow above it. The lighter, warmer air above the urban region tends to flow outward toward suburban areas, replenishing the buoyant, cooler air. Elevated AH profiles have the capacity to enhance the vertical ascent of urban thermals, facilitating the transport and dispersion of low-level motions due to warm advection and expediting the sea breeze front. This induces a stronger buoyant effect over the urban domain, marked by a 3–5 m s−1 increase in vertical wind speed where AH profiles are heightened. Surface roughness parameters play a crucial role, influencing the pull of cool sea breezes downwards due to their mixing effects. However, horizontal wind shear and frontal lifting, linked to these parameters, might delay the onset of the sea breeze front in the urban core. The spatial dimensions of the city significantly affect the urban heating effect from AH profiles, ultimately impacting the potency of sea breeze advection and modifying the thermal and dynamic profiles within the urban boundary layer.

Additionally, higher AH profiles alter the pressure gradient between the city and its surroundings, accentuated by a significant rise in ambient temperature (up to 2.1 °C) and wind speed (up to 4.6 m s−1). Consequently, alterations in AH profiles, sensible heating, and wind dynamics interact within the local city climate, particularly during peak hours (14:00 LT). This intensification of AH values amplifies advective flows, contributing to increased local warming and fostering a “regional low” effect. Such conditions enhance horizontal and vertical wind speeds over the city, potentially accelerating warm airflow from adjacent desert regions toward western Sydney. The study indicates a pronounced impact of the sea breeze, notably augmented over high-density residential zones, highlighting the complex interplay between AH profiles, local climatic dynamics, and the regional-scale synoptic flow.

Discussion

The quantification of AH fluxes in global cities exhibits significant variability, influenced by various factors such as population density, industrial activity, transportation, and energy consumption patterns. These variations necessitate the application of complex models and tailored measurements for each urban area. Previous studies, including Santamouris et al.23, have demonstrated substantial variability in AH fluxes across different cities, reflecting the complex interplay between urbanization and climate dynamics. For example, Tokyo, characterized by its dense population, extensive industrial operations, and high energy usage, recorded peak AH fluxes of approximately 7.5 W m2. This is indicative of how cities with heavy commercial activities and residential density can significantly contribute to localize warming. Similarly, cities like New York, London, and Shanghai showed AH values ranging from 4 to 6 W m2 during peak periods23,24. This variability not only underscores the importance of localized studies but also suggests that policy responses must be tailored to the specific characteristics of each urban environment to effectively manage heat emissions. The study of AH in Sydney is critical due to its significant implications for urban climate dynamics, public health, and energy systems. Sydney, like many global cities, is experiencing increasingly frequent and severe heatwaves as a result of climate change. AH—resulting from human activities such as building energy consumption, transportation, and industrial processes—exacerbates the UHI effect, leading to elevated localized temperatures. This intensification of heat contributes to rising health risks, including heat-related illnesses and mortality, increased energy demand for cooling, and a general decline in urban livability, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations.

In this study focusing on AH’s influence on Sydney’s urban climate, we observed a marked increase in sensible heat fluxes during peak afternoon hours, varying from 98.7 W m−2 to 266.5 W m−2, and from 59.9 W m−2 to 155 W m−2 during the evening. These findings are particularly significant as they align with established theories regarding UHIs, which posit that urbanization exacerbates heat retention due to the presence of impervious surfaces and human activities that generate heat25. The elevated sensible heat fluxes during afternoon hours can be attributed to the thermal properties of urban materials, which have higher heat capacity and conductivity compared to natural landscapes. These materials absorb solar radiation throughout the day, leading to higher heat storage and subsequent release during evening hours, contributing to prolonged warmth in urban settings. The notable increase in latent heat fluxes, ranging from 15.3 W m−2 to 35.3 W m−2 at 14:00 LT and from 4.1 W m−2 to 18.5 W m−2 at 18:00 LT, particularly over eastern Sydney, further underscores the importance of vegetation and urban greenery in regulating urban temperatures. This relationship between urban vegetation and temperature regulation aligns with findings from Bowler et al.26, which highlighted the capacity of urban greenery to mitigate UHI effects through shade provision and evapotranspiration. The variation in latent heat fluxes indicates that areas with more greenery and water bodies play a critical role in cooling the urban microclimate, underscoring the potential for green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience against heat. Urban planners and policymakers must thus consider the incorporation of green spaces as a viable strategy for climate adaptation and improving urban livability.

The modeled ambient and surface temperature increases of up to 2.1 °C and 8.0 °C, respectively, carry significant implications for urban heat stress, human health, and energy consumption. These temperature rises resonate with established research linking elevated urban temperatures to increased morbidity and mortality rates during heatwaves27. Higher ambient temperatures can lead to increased demand for cooling, consequently driving up energy consumption and contributing further to AH emissions. This creates a feedback loop where increased AH contributes to higher temperatures, resulting in greater energy demands that further exacerbate the UHI effect. Such dynamics call for integrated urban energy policies that not only address energy efficiency in buildings but also promote renewable energy sources to minimize the negative impacts of urban heat. Moreover, the significant alterations in wind patterns, with changes recorded up to 3.3 m s−1 during afternoons and 1.8 m s−1 in the mornings, illustrate the effects of AH on pollutant transport and microclimate dynamics. This observation is consistent with existing literature highlighting the role of AH in enhancing local wind patterns, which can exacerbate pollution accumulation in urban settings28. The intensified thermal gradients caused by AH can lead to stronger localized winds that either disperse pollutants or trap them in certain urban pockets, significantly affecting air quality and public health. Thus, understanding these interactions between heat dynamics and wind patterns is crucial for developing effective air quality management strategies in urban areas. The rise in convective PBL height, reaching up to 2013.7 m, also has critical implications for air quality management. An elevated PBL can hinder the effective dispersion of pollutants, potentially resulting in higher concentrations of harmful substances near ground level. This observation echoes findings from existing studies, which have shown that an increased PBL enhances the mixing height for pollutants but may also lead to a scenario where ground-level pollution concentrations remain elevated29. Consequently, the management of AH is vital for maintaining good air quality in urban environments, suggesting that addressing heat emissions can have broader benefits for public health and environmental quality. Despite the well-recognized role of AH in urban heat dynamics, there is a notable lack of comprehensive, city-wide data quantifying AH in Sydney. This absence of detailed information limits the accuracy of predictive models and constrains the development of effective urban planning and policy interventions. To address this gap, our study hypothesizes the potential impacts of AH at the city scale, utilizing existing data from similar urban environments and integrating it with advanced modeling techniques. This approach allows us to estimate AH’s contribution to urban overheating and identify its spatial variability, particularly in densely populated and industrial areas.

By filling this critical knowledge gap, our study not only enhances the understanding of AH’s influence on Sydney’s heat distribution but also provides a valuable framework for future studies in cities with similar climatic and urbanization challenges. The findings offer actionable insights for urban planners and policymakers, enabling the design of targeted heat mitigation strategies, such as increasing urban green cover, implementing reflective surfaces, and optimizing building energy systems. Moreover, the results can directly inform Sydney’s climate adaptation policies, providing evidence-based strategies to mitigate the impacts of AH, improve energy efficiency, and bolster urban resilience against future heat events. This study has broader implications beyond Sydney, offering transferable methodologies and insights that can be applied to other cities globally. By addressing a significant gap in AH studies, this research advances knowledge in urban climate resilience and provides a scientific basis for the development of sustainable, heat-resilient urban environments. The study’s findings are crucial for shaping climate adaptation strategies, contributing to the growing body of study on urban overheating and the impacts of human-induced climate stressors. Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations that warrant discussion. First, the analysis is primarily based on specific temporal and spatial scales; thus, the results may not fully capture longer-term trends and seasonal variations in AH fluxes. Seasonal changes in vegetation cover, building occupancy, and energy use patterns could significantly affect AH levels, indicating a need for seasonal studies that encompass varying climatic conditions and urban development scenarios to enhance the understanding of AH impacts. Such longitudinal studies would allow researchers to capture the dynamic interactions between urban heat, climate variability, and socio-economic factors, thereby providing a more comprehensive picture of urban climate resilience. Additionally, while the study focuses on eastern and South Sydney, extending the analysis to other regions with different urban configurations and climatic conditions would yield valuable insights into the generalized impacts of AH across various urban landscapes. Employing a comparative approach that examines cities with distinct characteristics—such as differing population densities, industrial bases, and vegetation cover—could elucidate the mechanisms underlying AH variability and its effects on urban climates globally.

Moreover, the study’s reliance on hypothetical scenarios may introduce uncertainties regarding the representativeness of the findings. Integrating remote sensing data and modeling approaches could enhance spatial insights into AH patterns across Sydney and facilitate comparisons with other urban areas. For instance, using satellite data to assess land surface temperatures and vegetation indices could provide additional context for understanding how urban heat dynamics interact with land cover changes. Future study should consider employing advanced modeling techniques, such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and machine learning algorithms, to simulate the complex interactions between AH, urban geometry, and atmospheric processes. Another potential avenue for future study is the investigation of community-level responses to AH and urban heat management. Understanding how different socio-economic groups experience heat and air quality challenges is crucial for developing equitable urban planning and public health initiatives. Research has shown that vulnerable populations, including the elderly and low-income communities, are disproportionately affected by heat events27. Exploring the social dimensions of urban heat could inform targeted interventions that enhance community resilience and improve the quality of life for marginalized groups. Finally, exploring the relationship between urban design features—such as building orientation, material choice, and green infrastructure—and their effectiveness in mitigating AH effects could yield valuable insights for policymakers and urban planners. This includes examining how the adoption of cool roofs, green walls, and urban trees can interact with AH to create a more balanced urban climate30,31,32,33. Such multifaceted approaches to urban design could significantly enhance cities’ resilience to heat extremes, ultimately leading to more sustainable urban environments. However, this study highlights the significant negative impacts of AH on urban climates, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted mitigation strategies to address urban heat stress and improve environmental quality.

Method

Model configuration

In this study, we employed the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF v4.3.1) model34, enhanced with the multilayer Building Effect Parameterization (BEP) and Building Energy Model (BEM) (WRF/BEP + BEM)35 system, to investigate the mesoscale climatic dynamics over Sydney. This coupled model system has been extensively validated for its ability to accurately reproduce diurnal variations of key meteorological variables such as near-surface air temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and urban energy consumption36. The configuration was specifically designed to capture the complex interactions between urban form, anthropogenic heat (AH) release, and local meteorological conditions during extreme heatwave periods (Table 1). For grid cells characterized by natural cover, we implemented the Noah Land-Surface Model (Noah LSM)37,38, which is a physically based scheme designed to simulate land-atmosphere exchanges of heat, moisture, and momentum. The model represents four soil layers, with thicknesses ranging from 10 cm at the surface to 1 m at depth. Key processes simulated by Noah LSM include surface energy fluxes (e.g., sensible and latent heat fluxes), soil moisture, soil temperature, surface runoff, and subsurface drainage. In this configuration, local land cover, vegetation types, soil properties, and roughness lengths were tailored to match the natural environment of the Sydney region, based on updated land use/land cover (LULC) data. This model setup ensured a realistic representation of the non-urban areas within the domain, capturing the distinct thermodynamic behaviour of natural land surfaces. For urban areas, we utilized the multilayer WRF/BEP + BEM system, which is specifically designed to simulate the complex energy exchanges within urban environments. The BEP model represents the urban canopy with multiple layers, enabling the simulation of building-induced turbulence, shadowing, and heat retention between buildings and streets. The BEM is further integrated to account for the energy exchanges that occur within buildings, including heat fluxes from walls, roofs, windows, and AH generated by Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems, appliances, and human activities. In this study, building characteristics such as heights, materials, and thermal properties were parameterized using data specific to Sydney’s urban landscape. This configuration allowed us to accurately simulate the contributions of building infrastructure to the urban energy balance, particularly during heatwave conditions. The WRF/BEP + BEM system accounted for the impacts of AH emissions on near-surface meteorological conditions, capturing the role of urban structures in modulating the thermal environment during periods of extreme heat.

Figure 7 illustrates the key components of the Noah-LSM, which includes parameterizations from Ek et al.38, Mitchell et al.45, and Chen et al.46. It also incorporates the BEP proposed by a study on urban surface exchange parameterisation for mesoscale models47 and the BEM introduced by a new building energy model coupled with an urban canopy parameterization for urban climate simulations48. These models are integrated within the multilayer Urban Canopy Model (UCM) and coupled with WRF model to simulate urban climate dynamics. This framework provides a comprehensive representation of the interactions between the urban environment and atmospheric processes, facilitating the study of urban heat islands, energy consumption, and meteorological conditions in urban areas. To assess the effects of AH on near-surface meteorological fields, we conducted a series of high-resolution WRF model experiments. The simulation period spanned a 2-month heatwave period, from January 1st, 2017, at 12:00 h to February 28th, 2017, at 00:00 h. A model spin-up period of 12 h was included, with the simulations starting on December 31st, 2016, at 00:00 h. The simulation domain was designed with three nested grids (d01, d02, and d03), with spatial resolutions of 4.5 km, 1.5 km, and 0.5 km, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 8). The finest domain (d03) covered the central urban areas of Sydney, allowing for high-resolution analysis of urban climate processes. For the initial and boundary conditions, we used the ERA-Interim reanalysis dataset, providing atmospheric forcing data that was dynamically downscaled to the model domains. Additionally, we incorporated high-resolution land use and land cover (LULC) data from the European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-2 satellite imagery49, at a 10-m resolution, into the innermost domain. This allowed for an accurate representation of the land surface characteristics, particularly the distribution of urban and natural areas within the region. Default WRF land use data was retained for d01, and d02 to simulate broader regional processes, as fine-scale land use is less influential at these scales. Recognizing the significant influence of urban environments on heat exchange processes, we made updated to the WRF urban parameter table to better reflect the specific characteristics of Sydney’s urban structure (Table S5). This included updating critical urban canopy parameters, such as building heights, street widths, roof albedo, and wall thermal conductivities. These adjustments were crucial for accurately simulating the effects of urban geometry and material properties on the heat retention and release within the city. By coupling the Noah LSM for natural surfaces with the BEP + BEM for urban areas, the model was able to resolve both natural and built environments at high spatial and temporal resolution. This hybrid approach allowed for a detailed investigation of urban heat island effects, AH release, and their impacts on local meteorological conditions during the extreme heatwave event. A framework diagram illustrating the components of the model configuration is provided (Fig. 7). This diagram outlines the interaction between the Noah LSM (for natural areas), the WRF/BEP + BEM system (for urban areas), the ERA-Interim reanalysis data, and the Sentinel-2 LULC inputs. It also illustrates the key outputs of the model for inner most domains, including near-surface temperature, wind, and energy fluxes, highlighting the integration of natural and urban processes in the simulation of Sydney’s climate.

Key components of the Noah Land-Surface Model (Noah-LSM)38,45,46, Building Effect Parameterization (BEP)47, and Building Energy Model (BEM)48 integrated into the multilayer Urban Canopy Model (UCM) and coupled with the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model for simulating urban climate dynamics.

WRF domain showing (a) dynamical downscaling with Domain 1 (d01) as the outermost parent domain at 4.5 km grid spacing, Domain 2 (d02) with 1.5 km grid spacing, and the innermost Domain 3 (d03) with 0.5 km grid spacing, covering the Greater Sydney area. Points A (east) and B (west) are used to draw horizontal-vertical cross-sections for analyzing meteorological conditions in Fig. 6. (b) Map of updated land use/land cover (LULC) derived from ESA Sentinel-2 imagery at a 10 m resolution for the innermost domain. The LULC map was created by the first author using WRF-Python for the WRF domain (https://github.com/NCAR/wrf-python) and ArcGIS 10.4 (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis), and does not require any permission. The LULC also shows the locations of surface meteorological stations in different urban environments: (1) Observatory, (2) Sydney Airport, (3) Olympic Park, and (4) Penrith.

Numerical design experiments

Understanding AH and its fluctuations amid future climate change are crucial due to its direct impact on local temperatures. AH, originating from human activities such as energy consumption and urban development intensifies urban heat and exacerbates the UHI effect. This escalation significantly affects public health by increasing heat-related stress and poses substantial challenges for energy management due to heightened cooling demands. Furthermore, it influences urban design and policy, necessitating the implementation of resilient strategies to mitigate rising temperatures and adapt to changing climatic conditions. These assessments are vital for developing effective mitigation measures, sustainable urban planning, and proactive policies that address the complexities of an evolving climate landscape. In this study, AH is represented as a singular fraction that is uniformly applied across all urban grid cells. Various AH profiles, denoted as AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4, were meticulously examined at the city scale (see Table 2). The AH values employed in this study were determined through a systematic and rigorous approach that integrates established literatures from urban climate study with tailored adjustments specific to the characteristics of Sydney. The studies50,51,52 provide detailed insights into the impact of AH on urban climates across different regions. A study50 observed maximum AH values of 54.4 W m−2, 32.7 W m−2, and 13 W m−2 in high, medium, and low-intensity areas of Sydney, respectively. Another study51 reported peak AH values of 25 W m−2, 75 W m−2, and 225 W m−2 over the Seoul metropolitan area, showing the influence of building height and urban structure on AH levels. Recently, a study reported52 an hourly peak AH value of 390 W m−2 in Singapore, highlighting the significant contribution of human activities and energy consumption to local temperature increases. However, in light of the absence of high-resolution AH data at the city scale, we relied on a widely accepted technique whereby AH emissions are scaled according to urban density. This methodology is underpinned by the understanding that denser urban environments, characterized by higher concentrations of buildings, vehicles, and human activities, inherently produce greater amounts of AH due to increased energy consumption, transportation, and industrial activities. To ensure the reliability and robustness of our AH estimates, we referenced empirical data and methodologies derived from analogous studies successfully implemented in other cities, such as Tokyo, London, and New York, where direct AH data were similarly limited. These studies have effectively demonstrated that scaling AH emissions by urban density offers a valid and realistic approximation of AH contributions across various urban zones. Furthermore, we modified the diurnal AH profile within our WRF model based on established patterns of human activity, energy consumption, and transportation cycles, thus ensuring that the timing and intensity of AH emissions are reflective of real-world conditions in urban areas.

This study is pioneering in its exploration of hypothesized AH profiles during heatwaves, and to our knowledge, no previous study has investigated these strategies comprehensively. This study marks the first of its kind, aiming to understand and simulate these AH profiles during periods of intensified heat. For the control scenario, the values for AH released progressively increase across low, medium, and high-density urban areas, ranging from 20 to 90 W m−2. In scenarios AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4, there are incremental increases in AH profiles across all density types. The values provided for different urban density settings across scenarios AH1, AH2, AH3, and AH4 illustrate a progressive increase in AH emissions. When comparing these scenarios, each density setting experiences a significant rise in heat generation as we transition from AH1 to AH4. Specifically, in low-density zones, there is a consistent upward trend from 100 to 380 W m−2, indicating a substantial escalation in heat output compared to the control scenario and each preceding AH scenario. Similarly, medium-density areas demonstrate a steady increase from 130 to 410 W m−2, reflecting a notable elevation in heat generation relative to their respective preceding scenarios. High-density urban settings exhibit a comparable pattern, rising from 170 to 450 W m−2, depicting intensified heat generation in densely populated urban environments across AH1 to AH4 scenarios. These increments clearly demonstrate a trend of amplified AH emissions across all urban density settings as the scenarios progress, reflecting an increasing impact on heat dynamics within urban areas. The thermal characteristics of roofs (albedo and emissivity) remain constant across all experiments, indicating consistent reflective properties (albedo: 0.15) and thermal radiation emission (emissivity: 0.85) for the studied roof surfaces in Sydney. The study conducted a comprehensive analysis to assess the influence of these distinct AH scenarios and their respective heating potentials. These four scenarios were thoroughly evaluated within numerical design, scrutinizing their impact on the urban environment’s thermal characteristics and heat distribution. The investigation of AH profiles was conducted at the city scale, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of their implications on urban meteorological phenomena and heat dynamics.

Model evaluation and validation

The evaluation metrics such as mean bias error (MBE), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), correlation coefficient (R), and index of agreement (IOA) were used to assess the performance of the WRF/BEP + BEM system provide critical insights into the model’s accuracy in simulating 2-m ambient air temperature. In this study, the model was compared with observed data from four stations (1) Observatory, (2) Sydney Airport, (3) Olympic Park, and (4) Penrith for the control scenario, with the results offering a comprehensive evaluation of the system’s predictive capability. The MBE, which measures the average bias, indicated a slight overestimation of the daily average 2-m ambient air temperature, with a mean bias of 0.569 °C. This bias, though minor, suggests a potential overestimation of AH contributions in urban areas, which could lead to inflated temperature predictions in highly built-up environments. This is an important finding, as it highlights the need for further refinement in how AH is modeled in urban heat simulations. Adjusting the model’s representation of AH could lead to a more accurate reflection of urban heating dynamics, particularly in high-density areas. The MAE and RMSE, which reflect the average magnitude of errors and emphasize larger discrepancies, respectively, show that the model performed well, with MAE ranging from 0.4 to 0.9 °C and RMSE between 0.5 and 0.9 °C. These relatively low error values indicate that the model accurately captured the temperature fluctuations across the diurnal cycle, replicating urban meteorological conditions with good precision. However, slight discrepancies were noted in simulating the diurnal temperature range, which may curtail from several factors, including local urban effects, cloud cover variations, microscale heat transfer processes, and data quality. These findings suggest that refining these elements could lead to further improvements in the model’s performance, particularly in accurately capturing the complexities of urban climate.

The high correlation coefficient (mean R = 0.982) indicates a strong linear relationship between the model’s predicted temperatures and the observed data, which confirms that the WRF/BEP + BEM system effectively mirrors real-world temperature patterns. This is further supported by the IOA values, which ranged from 0.95 to 0.97, with an average of 0.96, indicating good agreement between simulated and observed temperatures across all stations. These high values reflect the model’s robust performance, especially in replicating daytime warming and night-time cooling, which are critical aspects of urban climate dynamics. The simulated UHI intensity, ranging from 3.2 to 6.3 °C in high-density residential areas compared to surrounding rural landscapes, aligns well with observed local meteorological conditions, further validating the model’s efficacy. The evaluation results demonstrate that the WRF/BEP + BEM model not only replicates these temperature variations with statistical significance (p < 0.05) but also accurately simulates the 24-h diurnal temperature range, including the dew point temperature, which reflects uncomfortable urban conditions. However, the slight overestimation of daily average temperatures and the discrepancies in the diurnal range suggest potential biases related to the model’s representation of urban morphology, the accuracy of the urban biophysical parameters, and the input data used. These biases may also stem from simplifications inherent in the modeling schemes, particularly those used to represent heat transfer mechanisms and local urban effects. Addressing these factors could further improve the model’s ability to predict urban heat more accurately. The combination of these evaluation metrics offers a thorough understanding of the model’s strengths and areas for improvement. Despite minor discrepancies, the WRF/BEP + BEM system has proven effective in simulating urban temperatures and UHI effects, making it a valuable tool for regional meteorology forecasting and for exploring the local warming effects of AH. The results emphasize the importance of refining AH estimations and improving the representation of urban morphology in future iterations of the model, which would enhance its predictive power and its utility in informing urban heat mitigation strategies.

Data availability

The datasets utilized and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Khan, A. et al. Exploring the meteorological impacts of surface and rooftop heat mitigation strategies over a tropical city. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128(8), e2022JD038099 (2023).

Reimuth, A. et al. Urban growth modeling for the assessment of future climate and disaster risks: Approaches, gaps and needs. Environ. Res. Lett. 19(1), 013002 (2023).

Wang, L., Sun, T., Zhou, W., Liu, M. & Li, D. Deciphering the sensitivity of urban canopy air temperature to anthropogenic heat flux with a forcing-feedback framework. Environ. Res. Lett. 18(9), 094005 (2023).

He, C., Zhou, L., Yao, Y., Ma, W. & Kinney, P. L. Estimating spatial effects of anthropogenic heat emissions upon the urban thermal environment in an urban agglomeration area in East China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 57, 102046 (2020).

Shreevastava, A., Prasanth, S., Ramamurthy, P. & Rao, P. S. C. Scale-dependent response of the urban heat island to the European heatwave of 2018. Environ. Res. Lett. 16(10), 104021 (2021).

Khan, H. S., Santamouris, M., Paolini, R., Caccetta, P. & Kassomenos, P. Analyzing the local and climatic conditions affecting the urban overheating magnitude during the heatwaves (HWs) in a coastal city: A case study of the greater Sydney region. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142515 (2021).

Ulpiani, G., Ranzi, G. & Santamouris, M. Local synergies and antagonisms between meteorological factors and air pollution: A 15-year comprehensive study in the Sydney region. Sci. Total Environ. 788, 147783 (2021).

Nazarian, N. et al. Integrated assessment of urban overheating impacts on human life. Earth’s Future 10(8), e2022EF002682 (2022).

Hoffmann, R. Contextualizing climate change impacts on human mobility in African drylands. Earth’s Future 10(6), e2021EF002591 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Modeling the impacts of urbanization on summer thermal comfort: The role of urban land use and anthropogenic heat. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124(13), 6681–6697 (2019).

Shi, H., Xian, G., Auch, R., Gallo, K. & Zhou, Q. Urban heat island and its regional impacts using remotely sensed thermal data—A review of recent developments and methodology. Land 10(8), 867 (2021).

Yuan, C. et al. Mitigating intensity of urban heat island by better understanding on urban morphology and anthropogenic heat dispersion. Build. Environ. 176, 106876 (2020).

Fowler, H. J. et al. Anthropogenic intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2(2), 107–122 (2021).

Potgieter, J. et al. Combining high-resolution land use data with crowdsourced air temperature to investigate intra-urban microclimate. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 720323 (2021).

Masson, V., Lemonsu, A., Hidalgo, J. & Voogt, J. Urban climates and climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45(1), 411–444 (2020).

Hsu, A., Sheriff, G., Chakraborty, T. & Manya, D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 2721 (2021).

Santamouris, M. & Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 1, 100002 (2021).

Anenberg, S., Miller, J., Henze, D. A. V. E. N. & Minjares, R. A global Snapshot of the Air Pollution-Related Health Impacts of Transportation Sector Emissions in 2010 and 2015 1–48 (International Council on Clean Transportation, 2019).

Roe, S. et al. Contribution of the land sector to a 1.5 C world. Nat. Clim. Change 9(11), 817–828 (2019).

Zhou, B., Kaplan, S., Peeters, A., Kloog, I. & Erell, E. “Surface”, “Satellite” or “Simulation”: Mapping Intra-urban Microclimate Variability in a Desert City (2020).

Degirmenci, K., Desouza, K. C., Fieuw, W., Watson, R. T. & Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding policy and technology responses in mitigating urban heat islands: A literature review and directions for future research. Sustain. Cities Soc. 70, 102873 (2021).

Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. K., Mann, M. E. & Raymond, C. Anthropogenic warming and population growth may double US heat stress by the late 21st century. Earth’s Future 9(5), e2020EF001886 (2021).

Santamouris, M. et al. Urban heat island and overheating characteristics in Sydney, Australia. An analysis of multiyear measurements. Sustainability 9(5), 712 (2017).

Stewart, I. D. & Oke, T. R. Local climate zones for urban temperature studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93(12), 1879–1900 (2012).

Oke, T. R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 108(455), 1–24 (1982).

Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T. M. & Pullin, A. S. Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 97(3), 147–155 (2010).

Harlan, S. L., Brazel, A. J., Prashad, L., Stefanov, W. L. & Larsen, L. Neighborhood microclimates and vulnerability to heat stress. Soc. Sci. Med. 63(11), 2847–2863 (2006).

Klein, P. M., Hu, X. M. & Xue, M. Impacts of mixing processes in nocturnal atmospheric boundary layer on urban ozone concentrations. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 150, 107–130 (2014).

Rao, S. T. et al. On the limit to the accuracy of regional-scale air quality models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20(3), 1627–1639 (2020).

Khatun, R., Das, D., Khorat, S., Aziz, S. M., Anand, P., Mohan, M., Khan, A., Niyogi, D. & Santamouris, M. Urban scale rooftop super cool broadband radiative coolers in humid conditions. In Building Simulation, Vol. 17, No. 9, 1629–1651 (Tsinghua University Press, Beijing, 2024).

Khorat, S. et al. Cool roof strategies for urban thermal resilience to extreme heatwaves in tropical cities. Energy Build. 302, 113751 (2024).

Khan, A. et al. Urban cooling potential and cost comparison of heat mitigation techniques for their impact on the lower atmosphere. Comput. Urban Sci. 3(1), 26 (2023).

Mohammed, A., Khan, A. & Santamouris, M. Numerical evaluation of enhanced green infrastructures for mitigating urban heat in a desert urban setting. In Building Simulation, Vol. 16, No. 9, 1691–1712 (Tsinghua University Press, Beijing, 2023).

Skamarock, W. C. & Klemp, J. B. A time-split nonhydrostatic atmospheric model for weather research and forecasting applications. J. Comput. Phys. 227(7), 3465–3485 (2008).

Salamanca, F., Martilli, A., Tewari, M. & Chen, F. A study of the urban boundary layer using different urban parameterizations and high-resolution urban canopy parameters with WRF. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 50(5), 1107–1128 (2011).

Salamanca, F. et al. Assessing summertime urban air conditioning consumption in a semiarid environment. Environ. Res. Lett. 8(3), 034022 (2013).

Chen, F. & Dudhia, J. Coupling an advanced land surface–hydrology model with the Penn State–NCAR MM5 modeling system. Part I: Model implementation and sensitivity. Mon. Weather Rev. 129(4), 569–585 (2001).

Ek, M. B. et al. Implementation of Noah land surface model advances in the National Centers for Environmental Prediction operational mesoscale Eta model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108(D22), 1–16 (2003).

Hong, S. Y. & Lim, J. O. J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). Asia Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 42(2), 129–151 (2006).

Mellor, G. L. & Yamada, T. A hierarchy of turbulence closure models for planetary boundary layers. J. Atmos. Sci. 31(7), 1791–1806 (1974).

Dudhia, J. Numerical study of convection observed during the winter monsoon experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. J. Atmos. Sci. 46(20), 3077–3107 (1989).

Mlawer, E. J., Taubman, S. J., Brown, P. D., Iacono, M. J. & Clough, S. A. Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 102(D14), 16663–16682 (1997).

Bougeault, P. & Lacarrere, P. Parameterization of orography-induced turbulence in a mesobeta–scale model. Mon. Weather Rev. 117(8), 1872–1890 (1989).

Kain, J. S. The Kain–Fritsch convective parameterization: An update. J. Appl. Meteorol. 43(1), 170–181 (2004).

Mitchell, K. E. et al. The multi-institution North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS): Utilizing multiple GCIP products and partners in a continental distributed hydrological modeling system. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109(D7), 1–32 (2004).

Chen, F. et al. Description and evaluation of the characteristics of the NCAR high-resolution land data assimilation system. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 46(6), 694–713 (2007).

Martilli, A., Clappier, A. & Rotach, M. W. An urban surface exchange parameterisation for mesoscale models. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 104, 261–304 (2002).

Salamanca, F. & Martilli, A. A new building energy model coupled with an urban canopy parameterization for urban climate simulations—Part II. Validation with one dimension off-line simulations. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 99, 345–356 (2010).

European Space Agency. Overview of Sentinel-2 Mission. Copernicus https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s2-mission (2022).

Ma, S. et al. The impact of an urban canopy and anthropogenic heat fluxes on Sydney’s climate. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 255–270 (2017).

Kim, G., Cha, D. H., Song, C. K. & Kim, H. Impacts of anthropogenic heat and building height on urban precipitation over the Seoul metropolitan area in regional climate modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126(23), e2021JD035348 (2021).

Wang, A., Li, X. X., Xin, R. & Chew, L. W. Impact of anthropogenic heat on urban environment: A case study of Singapore with high-resolution gridded data. Atmosphere 14(10), 1499 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) of the Australian Government provided funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. and M.S.: conceptualized the numerical design. A.K.: collected and cured data, ran the WRF model, and visualized the results. K.V.: performed the local climate analysis. A.K.: wrote the original manuscript. M.S. supervised the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, A., Vasilakopoulou, K. & Santamouris, M. Exploring the potential impacts of anthropogenic heating on urban climate during heatwaves. Sci Rep 15, 3908 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83918-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83918-y