Abstract

Self-esteem, crucial for psychological well-being, can be enhanced through targeted interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). However, traditional CBT faces various accessibility barriers. Digital health interventions such as computerized CBT and mobile health (mHealth) applications offer potential solutions. Recent research suggests that brain oscillations, particularly theta rhythms, play a key role in memory consolidation. Combining computerized CBT with post-learning theta rhythm modulation may optimize and stabilize improvements in self-esteem and promote neuro-wellbeing. This six-month longitudinal study aimed to evaluate the synergistic effects of a computerized CBT intervention (GGSE) combined with post-training theta rhythm brain modulation on improving self-esteem in young adults with low self-esteem. Participants were randomly allocated to three groups: GGSE + theta audio–visual entrainment (AVE) with Cranio-Electro Stimulation (CES), GGSE + beta AVE + CES (active control), and GGSE only (control). The intervention lasted three weeks. Assessments of self-esteem, maladaptive beliefs, and mood were conducted at baseline, 21 days, 42 days, and six months post-baseline. Although post-treatment oscillatory entrainment did not enhance the long-term efficacy of the intervention, significant treatment effects persisted for six months across all groups. These results support the potential long-term efficacy of brief, game-like, digital CBT approaches for improving self-esteem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-esteem, the evaluation of one’s own worth, talents, and competencies, has been implicated in various determinants of well-being1. Low self-esteem has also been linked with various mental health issues including anxiety and depression2,3 and has been suggested to contribute to their development and maintenance3. Indeed, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders 54 has low self-esteem as a diagnostic, associative feature, risk factor or consequence in numerous disorders.

Although self-esteem is often considered a relatively stable trait, research findings suggest that it is malleable to treatment5. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a therapeutic approach rooted in learning principles, has been shown to be effective in treating low self-esteem6,7, and CBT models suggest low self-esteem is maintained by maladaptive self-beliefs and schemas8. Fennell, for instance, expanded on Beck’s work9 and proposed a model where individuals form a “bottom line” self-image schema (e.g., “I’m worthless”) based on past experiences. This schema influences information processing, leading to the formation of rigid maladaptive beliefs (e.g., perfectionism; “I must do everything perfectly”) intended to conceal this vulnerable schema. However, events challenging these beliefs activate the bottom line and trigger predictions of negative consequences (e.g., harsh judgment by others). CBT disrupts this cycle by reducing negative self-beliefs and increasing accessibility to more positive self-perceptions using strategies such as cognitive restructuring and behavioral adjustments. This enables individuals to become more self-compassionate, self-accepting and develop healthier self-perceptions.

Findings from a recent meta-analysis indicate that Fennell’s CBT approach yields medium to large effects in boosting self-esteem in adults across diverse populations, including those who are healthy, depressed, or anxious, with benefits sustained for at least three months post-treatment10. Considering depression measures inherently capture aspects of self-esteem3,11,12, studies have also consistently demonstrated superior long-term outcomes of CBT for depression and self-esteem compared to other therapeutic approaches, including pharmacological interventions13,14. This efficacy is evident in both in-person and virtual administrations of CBT15,16.

Despite its efficacy in clinical and non-clinical populations, however, there are significant barriers for receiving CBT treatment such as stigma, high costs, substantial time commitments, limited accessibility, and a shortage of trained professionals17,18. Moreover, many individuals with low self-esteem may not seek treatment because they don’t perceive their struggles as severe enough to warrant clinical intervention8 and are unaware of their increased vulnerability to psychopathology. There is a need for interventions for low self-esteem that are easily accessible and with widespread reach.

Computerized CBT and mobile health (mHealth) interventions have emerged as promising solutions, offering greater accessibility, flexibility, and significantly reduced costs compared to traditional CBT19. These digital platforms have the potential to deliver effective therapy to a broader population, overcoming the limitations of conventional face-to-face therapy. Although numerous CBT-based mHealth platforms exist, only a few are evidence based20,21. An example of such an evidence-based mobile-computerized CBT application is the GGtude platform22,23,24. Seventeen published studies including 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)25,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 and real-world data analyses36,37,38 have consistently indicated that daily use of this platform for a period of 2–4 weeks (for an average of 3–4 min a day) is associated with significant mental health benefits.

Among these, four RCTs conducted in the USA, Spain, Italy and Israel have included self-esteem measures25,26,30,31. These studies suggest that using various modules of the GGtude platform is associated with increased self-esteem compared with a waitlist control group and that these gains remain at follow-up assessments. For examples, a large (n = 315) fully remote RCT30, including people with serious mental illness, found large effect-size increases in self-esteem following 1-month training on the GGtude platform compared with a waitlist control group. These results were maintained at 1-month follow-up and replicated following crossover. Similar findings were found in another RCT with crossover design conducted in Spain25. In this RCT, students (n = 97) training with the relationship obsessions module, GGRO, of the GGtude platform showed medium effect-size increases in self-esteem compared with a waitlist control group. Again, these findings were maintained at 15-day follow-up and replicated following crossover.

A third RCT26 (n = 90) conducted in Israel found that two weeks of daily use with the body image module, GGBI, of the GGtude platform were associated with improved self-esteem scores that were maintained at 1-month follow-up. The fourth RCT conducted in Italy31 also used the GGRO module. Findings from this study indicated that students (n = 50) with subclinical symptoms of relationship OCD39 showed medium effect-size improvement in self-esteem relative to a waitlist control group that remained at follow-up assessment. However, an analysis using the reliable scale index (RSI)40 suggested reliable change in only 12% of these users. Consistent with findings from the above mentioned RCTs, are finding from a recent study using real world data analyses of the self-esteem module (GGSE)37. In this study, data of users that downloaded the app from Google Play or App Store and completed at least two assessment points (n = 1034) were analyzed. Results indicated large effect size improvements in self-esteem that were consistent with a dosage–response effect37.

Overall, findings from previous RCTs consistently support the efficacy of the GGtude platform25,26,30,31 in increasing self-esteem relative to waitlist control groups and indicate that such improvements persist for a period up to 1-month. However, the long-term efficacy of training on the GGtude platform remains underexplored, with no studies extending follow-up to six months. Moreover, given that CBT is grounded on learning principles, enhancing memory effects following a CBT based intervention could increase its efficacy and extend its long-term benefits. Daily training with the GGtude platform followed by an intervention aimed at enhancing memory consolidation may, therefore, boost its immediate and long-term effects.

Memory consolidation refers to the dynamic process by which newly acquired information is transformed into stable, long-lasting memory representations. It involves molecular, synaptic, and system-level changes that reinforce neural circuits, protecting the memory from decay or interference. This process, occurring during the critical post-learning period, is crucial for the persistence of new memories. Over time, these changes contribute to the gradual integration of new information into pre-existing networks41,42.

Recent evidence suggests that interventions during this time window of memory consolidation can significantly enhance the retention of learned material. Specifically, modulating brain oscillations—particularly theta rhythms—has been shown to optimize neural synchrony, thereby amplifying learning effects43,44,45,46,47. Effective communication within brain networks is facilitated by increased synchrony in neuronal firing48,49. These network oscillations influence the precise timing of neural activity both within and between brain regions, which is crucial for representing and encoding information45,50. Consequently, post-learning replay of neural activity from the encoding phase, which supports consolidation, can be strengthened through the optimization of neural transmission by enhancing synchrony at specific frequencies. Given the evidence highlighting the importance of theta rhythms in successful encoding and retrieval43,44,46,47,51,52, and considering that both retrieval and consolidation involve reinstatement or replay, modulating theta rhythms after learning potentially provides a means to promote consolidation53,54,55,56,57,58.

Techniques such as EEG neurofeedback (NFB) and transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), have demonstrated the ability to strengthen memory consolidation by targeting theta activity. In previous research55, we have used EEG NFB to enable participants to selectively increase theta power in their EEG spectra following episodic memory encoding. Free recall assessments immediately following the interventions, 24 h later, and 7 days later all indicated benefit to memory of theta NFB. Similar results were obtained by 3 Hz theta tACS in episodic memory53. These results complement our earlier findings that theta NFB similarly improves consolidation of procedural learning56 and spatial memory54, which were all tested up until one week post-intervention.

Alongside EEG NFB and tACS, another method of modulating oscillatory neural activity is audio-visual entrainment (AVE), which uses rhythmic auditory and visual stimuli to potentiate desired frequencies of brain electrical activity. Research on visual processing has demonstrated that entrainment can increase targeted oscillatory activity, influencing spiking responses and improving behavioral performance59,60. Moreover, AVE upregulation of theta-frequency activity was reported for improving episodic memory retrieval61. Since memory consolidation involves stabilizing and integrating newly acquired information into long-lasting memory networks42, this is extremely relevant for interventions like CBT that rely on altering maladaptive beliefs and schemas, also due to the hippocampus-dependent nature of the cognitive components in CBT62. Our goal, therefore, was to explore whether post-learning theta entrainment could optimize and stabilize CBT outcomes, enhancing the long-term effects of self-esteem interventions delivered via mobile platforms.

In this study, we hypothesized that combining an accessible, mobile-delivered, personalized form of CBT (via the GGtude platform) with post-learning theta rhythm modulation could further improve self-esteem treatment response, optimize the intervention, and achieve longer-term effects. We expected that the synergistic effect of these two methods would lead to higher response rates, maximize the therapeutic impact, and stabilize its effects over a longer duration. To test this hypothesis, we assessed whether using theta entrainment techniques post-training with the GGtude platform could enhance and prolong the platform’s efficacy on self-esteem, with a particular focus on outcomes over a 6-month period. Two control groups were included in this study: an active control Beta group, as in our previous studies53,54,55, and a GGSE only control group in which participant used the GGtude platform with no brain entrainment method. As there are no established criteria for clinically significant improvement on the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES), we used the RCI40 to assess reliable and meaningful change of each participant on the RSES scale. We also examined the effects of the intervention on related psychological constructs, such as mood, social anxiety, maladaptive perfectionism, self-compassion, dysfunctional attitudes, and social comparison tendencies, all of which have been previously found to be associated with self-esteem63,62,63,64,65,68. This longitudinal study design allowed us to investigate not only the immediate benefits but also the durability of treatment effects, a critical factor in the broader implementation of scalable mHealth interventions for self-esteem.

Methods

Participants

179 young adults, recruited in campus communities and nearby areas, completed the RSES69 on the Qualtrics online platform. Of those, 85 young adults (52 females; mean age 23.3 years, SD 3.3 years, age range 18 to 37) who showed low self-esteem scores (RSES < 16) participated in this study.

Exclusion criteria were self-reported hearing problems, neurological/psychiatric problems, learning disabilities/ADD, regular drug use (prescription/recreational), pacemaker, epilepsy, regular use of alcohol, previous head injuries/head tumor/stroke, ear piercing, previous injury to the skin on the earlobe (peeling, redness, scarring, etc.). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: Theta group (20 F, 11 M, mean age 23.4 years, SD 3.8 years), Beta group (17 F, 12 M, mean age 23.3 years, SD 3.3 years), or GGSE only control group (15 F, 10 M, mean age 23.1 years, SD 2.8 years). Participants received monetary compensation of 400 NIS for their participation. The study protocol and publication were approved by Reichman University, Herzliya, Israel (No: 2020015_P). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines.

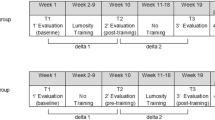

Experimental design

At T0, participants in the Theta and Beta groups were asked to arrive at the lab to collect the AVE + CES (Cranio-Electro Stimulation) device and to undergo a training session with an experimenter. From that point on, all participants conducted the experiment at home. They were asked to use GGSE five days per week (excluding Fridays and Saturdays) over a period of three weeks, for a total of 15 days, at the same time each day. Following the completion of each daily GGSE training (5 min/day), participants used the AVE + CES device (20 min/day), in a theta or beta session mode, depending on the group they were randomly assigned to. The GGSE-only control group participants went through the same experimental procedure, but without the use of the AVE + CES device. All participants were requested to complete web-based assessment, with questionnaires relating to self-esteem, maladaptive beliefs and mood at baseline (T0), 21 days following baseline—after the completion of the intervention (T1), 42 days following baseline (T2) and 6 months following baseline (T3). An experimenter conducted daily follow-ups with all participants via Zoom or phone call, for technical support and to verify the completion of the daily training. Participants did not use the app after the initial intervention period (first three weeks of the experiment).

CBT intervention

The GGtude platform was specifically designed to take advantage of mobile phone technology and use interactive, short, touch-screen based intervention to reduce psychological symptoms )e.g22,23,25. The self-esteem module of the platform (GGSE) includes 46 training levels targeting 11 maladaptive beliefs/metacognitions related to low self-esteem. GGSE consists of game-like interactions facilitating accessibility to adaptive self-statements relating to the appraisals of thoughts, emotions, and events related to self-esteem.

At the onboarding stage, participants received a brief psychoeducation script about the impact of self-talk on mood. They then engage in short, game-like interactions aimed at promoting more adaptive self-talk. Each training session presents self-statements consistent with maladaptive beliefs (e.g., “I must be perfect to be accepted”) or inconsistent with such beliefs (e.g., “Imperfection is part of being human”). Each daily session targets a specific maladaptive belief (e.g., perfectionism, intolerance of uncertainty, self-efficacy, over-estimation of social threat, fear of abandonment) or metacognition (e.g., positive beliefs about comparisons and about self-criticism). Users are instructed to discard maladaptive statements by swiping them in an upward motion. They are instructed to “embrace” helpful statements by swiping them downwards towards themselves.

When introducing new levels that address a particular belief, the app presents a screen explaining the rationale for challenging this belief. For instance, before addressing self-criticism, users see: “Research shows that self-criticism is associated with depression, anxiety and low self-esteem. However, people with low self-esteem often believe self-criticism is useful. Let’s try and challenge this belief!” After completing a level, users take a brief memory quiz, selecting one of three self-esteem-enhancing statements featured in the level. Upon completing three levels, the app advises: “You’ve reached the recommended amount of training for today. To get the best results, continue practicing tomorrow”, encouraging users to conclude their session and resume training the following day. The duration of each daily session is approximately 5 min.

AVE + CES stimulation

After each GGtude daily session, participants in the stimulation conditions received 20 min of either theta entrainment at 5.5 Hz, or beta entrainment at 15 Hz, depending on their assigned group. Entrainment was generated by exposure to rhythmically flashing lights, pulsing pure tone sounds and mild electric currents oscillating at theta or beta frequency. A commercially available device (DAVID DELIGHT PRO by Mind Alive, Inc., Edmonton, Canada) was used to administer visual stimulation (via LED lights embedded on the inner edge of darkened eyeglasses), pulsed tones (via headphones) and CES (via earlobe electrodes, using a conductive gel). All subjects were instructed to attend to the lights and sounds and not to fall asleep. Participants could close their eyes or leave them slightly open during the entrainment period in accordance with their personal comfort preference, as the lights remained visible with eyes closed61.

Behavioral assessments

To thoroughly investigate the multilayered nature of self-esteem pre- and post- CBT intervention, we considered a range of psychological constructs that have been associated with low self-esteem (see detailed description of the measures below). For instance, we examined the effects of the intervention on the relentless pursuit of unattainable standards (i.e., perfectionism; as measured by the MPS)63,70, the tendency for upward social comparisons (as measure by the INCOM)64, the need of others’ approval68 (i.e., dysfunctional attitudes; as measured by the DAS) and fears of negative evaluation and social rejection (i.e., social anxiety; as measured by the SIAS)66. Similarly, we assessed symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress that have been closely linked to self-esteem (as measures by DASS), with lower self-esteem often found in individuals experiencing higher levels of these negative emotional states65. We also measured self-compassion (measured by the SCS) that has shown to be positively associated with self-esteem levels and buffer against low self-esteem, seemingly by promoting a kinder, more forgiving self-view67. Together, these tools provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex and interrelated factors that influence self-esteem, enabling us to assess intervention effects. Overall, the following questionnaires were provided for participants to complete at T0, T1, T2, and T3: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)71; the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS)70; the Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM)64; the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS)68; the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS)66; the short version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS)65 and the short form of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)67.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)69,71 ranges from 0 to 40 (with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem) and consists of 10 statements that assess the individual’s self-esteem, for example: “In total, I’m happy with myself.” The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”. RSES internal consistency: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.85; T1 = 0.88; T2 = 0.87; T3 = 0.89.

The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) is a shortened version of the original 45-item MPS70 which comprises three subscales (five-items per subscale) measuring self-oriented perfectionism, other-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism, with higher scores indicating greater perfectionism tendencies. Participants were asked to rate each item on a seven-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Total scores were used in this study. MPS internal consistency: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.74; T1 = 0.77; T2 = 0.74; T3 = 0.73.

The short version of the depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS)65 is a 21-item (DASS-21) self-report questionnaire listing negative emotional symptoms that is divided into three subscales measuring depression, anxiety and stress (seven items per subscale). The items are rated on our-point scales (0 = ”Does not relate to me at all,” 3 = “Relates to me greatly, or most of the time”). The total score was used in this study, with higher scores indicating higher levels of general distress72. DASS internal consistency was very high: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.90; T1 = 0.93; T2 = 0.94; T3 = 0.92.

The short form of the self-compassion scale (SCS) consists of 12 items. The scale assesses the positive and negative aspects of the three main components of self-compassion: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation and mindfulness versus over-identification67, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion. The items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from “almost never” to “almost always”. SCS internal consistency was: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.79; T1 = 0.84; T2 = 0.85; T3 = 0.88.

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) concise version is a self-report questionnaire, consisting of 17 items on a scale from 1 (“do not agree at all”) to 7 (“completely agree”), with scores ranging from 17 to 119, designed to identify and measure cognitive distortions associated with depression68. For example: “If I partly fail, it is as bad as being a complete failure”. The higher the score, the more dysfunctional attitude an individual possesses. DAS internal consistency was very high: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.88; T1 = 0.91; T2 = 0.89; T3 = 0.91.

The Social Comparison Scale (INCOM) consists of 11 items and assesses the general tendency to compare oneself to others. People are given statements about their self-comparisons with others64. The items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. INCOM internal consistency: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.81; T1 = 0.84; T2 = 0.83; T3 = 0.87.

The social interaction anxiety scale (SIAS) consists of 20 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 80. The items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4: “does not describe me at all” to “strongly describes me”. All the items are self-statements describing reactions to social interactions. For example: “I get nervous if I have to speak with someone in authority (teacher, boss, etc.)”66. SIAS internal consistency was very high: Cronbach’s α T0 = 0.92; T1 = 0.94; T2 = 0.94; T3 = 0.93.

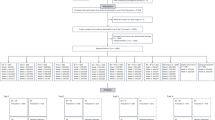

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.0 (R Core Team, 2024). Analysis of Variance models were conducted with afex package and follow up analyses were conducted with the emmeans package. Imputation of missing values from the dataset was conducted using the mice package73. Baseline comparisons across groups were conducted with one-way ANOVAs for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. The primary outcome (self-esteem, RSES) and Secondary outcomes (DAS, MPS, SCS, INCOM, DASS, SIAS), were analyzed using a Group × Time (T0, T1, T2, T3) RM-ANOVA. Partial eta-squared and Cohen’s d were calculated.

Results

Comparison of study groups

Before examining the effects of app use and neuromodulation, differences in baseline scores (T0) on all the study scales, as well as differences in participants age and gender, were analyzed across groups. No significant difference between groups were found for participant’s age (F(2,82) = 0.06, η2 = 0.00, p = 0.944), gender (2(2) = 0.24, p = 0.887), or scores on baseline measures (Table 1).

Mean of all total scale scores, including SD, per group, at the four time points, are described in Table 2.

Primary outcome–improvement over time on self-esteem

The scores on the RSES scale were submitted to a Group (Theta/Beta/GGSE only control) X Time (T0, T1, T2, T3) ANOVA to assess Time X Group interactions as well as main effects of Time and Group. No significant effect was found for Group X Time interaction (F(5,214) = 0.89, η2p = 0.02, p = 0.491) or Group (F(2,82) = 0.25, η2p = 0.01, p = 0.778) (Fig. 1). However, a significant main effect was found for Time (F(3,214) = 25.18, η2p = 0.23, p < 0.001).

Exploratory follow-up analyses of our primary outcome were performed to have a clearer view of the trajectory of each group on our primary outcome measure. Participants in all groups demonstrated significant improvements between baseline, and post-treatment assessments which were maintained at all consequent follow-up assessments (Table 3).

Reliable change evaluates whether the scores of an individual on a particular measurement changed significantly more than would be expected given measurement error (i.e., larger than that reasonably expected due to measurement error alone). The evaluation of such change provides an understanding of the extent to which change after treatment is reliable40. We used the RCI40 to assess reliable change of each participant on the RSES scale.

The calculation of the RCI requires estimates of a scale’s internal consistency and standard deviation for a given population. The threshold for reliable change is calculated as 1.96 times the standard error of the difference between scores of a measure administered on two occasions. The standard error of measurement (SE) was first calculated using:

(where s1 = standard deviation at pre-test and rxx = the internal consistency of the measure) and the standard error of the difference score (Sdiff) derived as:

Finally, RCI was calculated:

(where X2 = individual post-test and X1 = individual pre-test).

The RCI on the RSES scale was calculated for each participant in each of the groups from T0 (pre-training) to T3 (6-months follow up). The following percentages of improvement were obtained for each group: 22.6% for the Theta group (seven participants), 13.8% for the Beta group (four participants), and 24% for the GGSE only group (six participants). Overall, 20% (17 participants) of all participants achieved reliable clinical change. To determine whether there were significant differences among the three independent groups in the proportion of participants achieving clinically significant change, we performed a chi-squared test of independence. The results indicated no significant difference between the groups (χ2 = 1.08, d.f. = 2, p = 0.58). Results are shown in Table 4.

Secondary outcomes

The effects of Group and Time were examined for additional symptom and process scales (DAS, MPS, SCS, INCOM, DASS, SIAS). In all the scales, neither Group X Time interaction effects nor the main effect of Group (except the SIAS) were significant (see Table 5).

As in our primary variable, the only significant effects found were the main effect of Time (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

In the current longitudinal RCT, we examined the immediate and long-term effects of oscillatory neural modulation on the consolidation of a mHealth CBT-based intervention for self-esteem. We hypothesized that daily training with the self-esteem track of the GGtude platform (GGSE) followed by an intervention designed to enhance memory consolidation will result in a synergistic effect boosting the immediate and long-term effects of the intervention.

Our findings indicated medium to large effect sizes of the intervention evaluated immediately following and at the 6 months follow-up. However, contrary to our main hypothesis, our results did not support the synergistic effect of combining the intervention with theta oscillatory modulation. The theta and beta (active control) modulation groups exhibited similar benefits to the GGSE only non-modulation control group, as measured up to 6 months following the intervention.

Previous RCTs25,26,30,31 and one study using real world data37 have consistently demonstrated the efficacy and effectiveness of training with various modules of the GGtude platform in improving self-esteem. This is the first RCT, however, to assess the GGSE module of the platform that specifically targets maladaptive cognitions implicated in the maintenance of low self-esteem. This is also the first published RCT comparing the effectiveness of the GGtude platform with active control groups. The findings from this study, therefore, lend further support to the efficacy of GGSE in improving self-esteem as well as related psychological constructs. Moreover, findings from this study indicate that improvement in self-esteem was maintained at all subsequent time points including at the 6-month follow-up, as well as a significant proportion of participants (20%) reaching clinically meaningful improvement as indicated by the RCI of RSES. These results provide additional evidence to support the long-term maintenance of CBT for self-esteem.

The training exercises on the GGtude platform were designed to change the relative activation of adaptive and maladaptive cognitions such that the adaptive cognitions would be more easily retrieved than the maladaptive ones36. GGSE targets maladaptive cognitions known to be implicated in the maintenance of low self-esteem such as self-criticism, perfectionism and the tendency to compare. Repeated exposure to self-statements challenging these beliefs may increase users’ ability to generate and retrieve alternative self-statements promoting more positive self-view. The repeated pairing of self-referential pronouns with action words (verbs) with positive meaning during these exercises may also increase users’ positive implicit self-esteem74. Also, the brief psychoeducation scripts provided during these daily exercises may help motivate users and consolidate users’ understanding of basic CBT principles75.

Contrary to our main hypothesis, findings indicate no advantage for theta oscillatory modulation. Both theta and beta (active control) modulation groups exhibited similar benefits to the GGSE only (non-modulation) control group, as measured up to six months following the intervention. There are several possible reasons why the predicted benefit of post-training theta upregulation was similar to that of post-training beta upregulation and GGSE only groups.

One possible explanation for why our findings indicates no advantage for theta oscillatory modulation, is that bolstering memory consolidation via theta upregulation may be less effective in benefiting CBT-based improvement due to the mnemonic nature of the effects of the GGSE intervention. Although we have demonstrated that post-acquisition theta upregulation improves retention of various types of declarative memory and of the early stages of procedural motor skill learning53,54,55,56,57, the changes in attitude engendered by the intervention might be based on a different type of learning, leading to incremental practice-based modification of beliefs and behaviors. These might be more similar to the slow gradual changes in the extended phases of procedural learning, which are not dependent on the hippocampus76, and therefore not necessarily affected by theta upregulation.

In this study, due to the device settings, we employed theta entrainment at a frequency of 5.5 Hz. In our previous brain stimulation (via tACS) study53 theta was set at 3 Hz. Prior studies found 3 Hz to be the theta band frequency most strongly implicated in memory consolidation77. It is possible that a frequency of 3 Hz, or individually determined theta peak frequency entrainment, would be better for consolidating new therapeutic learning.

In addition, the distinct outcomes observed in the present study in which we used AVE with CES, as opposed to tACS53, and NFB54,55 in our previous research, can be understood in light of their differing neurophysiological mechanisms. AVE + CES, which relies on rhythmic sensory stimulation and mild cranial electrical currents, exerts its effects through the broad modulation of neural networks. Specifically, AVE attempts to entrain brain oscillations by presenting external auditory and visual stimuli at frequencies aimed at synchronizing endogenous rhythms, while CES influences overall neural excitability by delivering mild electrical currents59,58,61. This method inherently influences large-scale neural systems rather than modulating specific circuits or regions implicated in cognitive and emotional functions.

In contrast, tACS delivers alternating electrical currents directly to the scalp at frequencies designed to match and modulate endogenous brain rhythms. Since tACS (as opposed to NFB and AVE + CES) is focused on particular scalp locations, the selection of the most effective montage for stimulating brain areas involved in consolidation processes is important. This method exerts more precise control over neuronal oscillations, leading to phase alignment of neuronal firing in targeted regions. By influencing more localized cortical circuits, tACS can modulate functional connectivity between brain regions involved in cognitive processes, such as the hippocampal-cortical networks crucial for memory consolidation78.

In addition, NFB represents an individualized and proactive approach, offering real-time feedback based on a participants’ brain activity. This method allows for dynamic training of specific brain states, as participants are reinforced for achieving desired neural oscillatory patterns. The adaptability of NFB enables precise and individualized modulation of brain states, resulting in targeted interventions that can potentially optimize neurocognitive outcomes58.

The mechanistic differences between these three methods help explain the results observed in this study. AVE + CES, with its broader, less focused modulation, likely lacks the specificity to effectively influence the neural circuits underpinning self-esteem and related cognitive functions for optimal therapeutic outcomes. Determining whether theta upregulation of the consolidation of new learning can benefit CBT-based changes if different stimulation methods are employed, or whether theta increases cannot in principle aid the strength of CBT-based interventions, seemingly requires further research.

The current study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and our study included multiple measures. A larger sample size may have provided the statistical power to detect smaller effect-size interactions after correcting for multiple comparisons. Although several RCTs have shown the relative efficacy of training on the GGtude platform compared with waitlist control groups, inclusion of such an additional control group may have provided further insights into the differences between groups. Also, the age range of participants in our sample was relatively restricted (between 18 and 37 years) preventing generalization of the results to wider age groups. In addition, although participants were monitored for compliance, conducting the intervention at home may introduce variability in the environment and adherence to protocol, which could affect the outcomes.

Another potential limitation of our study is the possibility that regression to the mean may have influenced the results. Participants were selected based on low self-esteem and might naturally show some improvement over time independent of the intervention. However, several factors mitigate this concern. For instance, the groups were comparable at baseline, reducing the likelihood that extreme values in any particular group skewed the results and ensuring that any changes observed are less likely due to statistical artifacts. Also, we observed positive changes across multiple psychological measures, including self-esteem, processes measures (e.g. perfectionism, the tendency to compare) and symptoms (e.g., depression and anxiety). This suggests that the intervention produced genuine effects rather than being solely due to regression to the mean on one measure. Moreover, these improvements persisted across all follow-up assessments over six months. Importantly, regression to the mean typically does not account for sustained improvements over an extended period. Additionally, our findings align with those from four randomized controlled trials conducted in the USA, Spain, Italy, and Israel25,26,30,31 that included self-esteem measures. These studies found that using various modules of the GGtude platform led to increased self-esteem compared with a waitlist control group, with gains maintained at follow-up evaluations. Therefore, the replication of positive outcomes across diverse populations and settings strengthens the argument that the improvements are unlikely to be solely due to regression to the mean.

In conclusion, while the neuromodulatory manipulation did not achieve its hypothesized benefit, the finding that the intervention benefits persisted for 6 months after treatment is an important addition to our prior findings22,23,25,37. We believe that this data further supports using this CBT-based intervention as an effective, long-lasting method of improving self-esteem and neuro-wellness.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the figshare repository, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27022297 .

References

MacDonald, G. & Leary, M. Individual Differences in Self-Esteem The Guilford Press. (2012).

Silverstone, P. H. & Salsali, M. Low self-esteem and psychiatric patients: part I - the relationship between low self-esteem and psychiatric diagnosis. Ann. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2, 2 (2003).

Sowislo, J. F. & Orth, U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 139, 213–240 (2013).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders American Psychiatric Association. (2013).

Fraley, R. C. & Roberts, B. W. Patterns of continuity: a dynamic model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychol. Rev. 112, 60–74 (2005).

Fanning, P. & McKay, M. Self-Esteem: A Proven Program of Cognitive Techniques for Assessing, Improving, & Maintaining Your Self-Esteem. New Harbinger Publications, Inc. (2016).

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T. & Fang, A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of Meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 36, 427–440. (2012).

Fennell, M. J. V. Low Self-Esteem: a cognitive perspective. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 25, 1–26. (1997).

Beck, A. T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders International Universities. (1976).

Kolubinski, D. C., Frings, D., Nikčević, A. V., Lawrence, J. A. & Spada, M. M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of CBT interventions based on the Fennell model of low self-esteem. Psychiatry Res. 267, 296–305 (2018).

Orth, U. & Robins, R. W. Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 455–460 (2013).

Shahar, G. & Davidson, L. Depressive symptoms erode self-esteem in severe mental illness: a three-wave, cross-lagged study. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 71, 890–900 (2003).

Hollon, S. D. et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 62, 417–422 (2005).

DeRubeis, R. J. et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 62, 409–416 (2005).

Andrews, G. et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 55, 70–78 (2018).

Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H. & Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 47, 1–18 (2018).

Andrade, L. H. et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol. Med. 44, 1303–1317 (2014).

Price, M. et al. mHealth: a mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective Mental Health Care. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 21, 427–436 (2014).

Donker, T. et al. Economic evaluations of internet interventions for mental health: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 45, 3357–3376 (2015).

Marshall, J. M., Dunstan, D. A. & Bartik, W. Clinical or gimmickal: the use and effectiveness of mobile mental health apps for treating anxiety and depression. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 54, 20–28 (2020).

Torous, J., Levin, M. E., Ahern, D. K. & Oser, M. L. Cognitive behavioral mobile applications: clinical studies, Marketplace Overview, and Research Agenda. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 24, 215–225 (2017).

Pascual-Vera, B., Roncero, M., Doron, G. & Belloch, A. Assisting relapse prevention in OCD using a novel mobile app–based intervention: a case report. Bull. Menninger Clin. 82, 390–406 (2018).

Roncero, M., Belloch, A. & Doron, G. A novel approach to challenging OCD related beliefs using a mobile-app: an exploratory study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 59, 157–160 (2018).

Oron, Y., Ben David, B. M. & Doron, G. Brief cognitive-behavioral training for tinnitus relief using a mobile application: a pilot open trial. Health Inf. J. 28, 146045822210834 (2022).

Roncero, M., Belloch, A., Doron, G. & Can Brief Daily training using a Mobile App Help Change Maladaptive beliefs? Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 7, e11443 (2019).

Aboody, D., Siev, J. & Doron, G. Building resilience to body image triggers using brief cognitive training on a mobile application: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 134, 103723 (2020).

Abramovitch, A., Uwadiale, A. & Robinson, A. A randomized clinical trial of a gamified app for the treatment of perfectionism. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 73–91 (2024).

Akin-Sari, B. et al. Cognitive training via a Mobile application to reduce obsessive-compulsive-related distress and cognitions during the COVID-19 outbreaks: a Randomized Controlled Trial using a subclinical cohort. Behav. Ther. 53, 776–792 (2022).

Akin-Sari, B. et al. Cognitive training using a mobile app as a coping tool against COVID-19 distress: a crossover randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 311, 604–613 (2022).

Ben-Zeev, D. et al. A smartphone intervention for people with Serious Mental illness: fully remote Randomized Controlled Trial of CORE. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e29201 (2021).

Cerea, S. et al. Reaching reliable change using short, daily, cognitive training exercises delivered on a mobile application: the case of relationship obsessive compulsive disorder (ROCD) symptoms and cognitions in a subclinical cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 276, 775–787 (2020).

Cerea, S. et al. Cognitive behavioral training using a Mobile Application reduces body image-related symptoms in high-risk Female University students: a randomized controlled study. Behav. Ther. 52, 170–182 (2021).

Cerea, S. et al. Cognitive training via a mobile application to reduce some forms of body dissatisfaction in young females at high-risk for body image disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Body Image. 42, 297–306 (2022).

Gorelik, M., Szepsenwol, O. & Doron, G. Promoting couples’ resilience to relationship obsessive compulsive disorder (ROCD) symptoms using a CBT-based mobile application: a randomized controlled trial. Heliyon 9, e21673 (2023).

Podoly T. S., Even Ezra, H. & Doron, G. A randomized controlled trial evaluating an mHealth intervention for anger-related cognitions in misophonia. J. Affect. Disord. 379, 350–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.03.060 (2025).

Gamoran, A. & Doron, G. Effectiveness of brief daily training using a mobile app in reducing obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms: examining real world data of OCD.app - anxiety, mood & sleep. J. Obsess. Compuls. Relat. Disord. 36, 100782 (2023).

Giraldo-O’Meara, M. & Doron, G. Can self-esteem be improved using short daily training on mobile applications? Examining real world data of GG self-esteem users. Clin. Psychol. 25, 131–139 (2021).

Doron, G., Derby, D. & Gamoran, A. Gamifying Mental Health Treatment: A Mobile Interface Design for PTSD Intervention. In ACM, Yokohama, Japan, 19 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706599.3720074 (2025).

Doron, G., Derby, D. S. & Szepsenwol, O. Relationship obsessive compulsive disorder (ROCD): a conceptual framework. J. Obsess. Compuls Relat. Disord. 3, 169–180 (2014).

Jacobson, N. S. & Truax, P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 59, 12–19 (1991).

Dudai, Y. The Neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the Engram? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 51–86 (2004).

McGaugh, J. L. Memory–a century of consolidation. Science 287, 248–251 (2000).

Burke, J. F. et al. Synchronous and asynchronous Theta and Gamma Activity during episodic memory formation. J. Neurosci. 33, 292–304 (2013).

Burke, J. F. et al. Theta and high-frequency activity mark spontaneous Recall of episodic Memories. J. Neurosci. 34, 11355–11365 (2014).

Fell, J. & Axmacher, N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 105–118 (2011).

Hanslmayr, S. et al. The relationship between Brain oscillations and BOLD Signal during memory formation: a combined EEG–fMRI study. J. Neurosci. 31, 15674–15680 (2011).

White, T. P. et al. Theta power during encoding predicts subsequent-memory performance and default mode network deactivation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 2929–2943 (2013).

Fries, P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 474–480 (2005).

Klimesch, W. Memory processes, brain oscillations and EEG synchronization. Int. J. Psychophysiol. Off J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 24, 61–100 (1996).

Düzel, E., Penny, W. D. & Burgess, N. Brain oscillations and memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 143–149 (2010).

Bastiaansen, M. & Hagoort, P. Event-Induced Theta responses as a window on the dynamics of memory. Cortex 39, 967–992 (2003).

Nyhus, E. & Curran, T. Functional role of gamma and theta oscillations in episodic memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 1023–1035 (2010).

Shtoots, L. et al. Frontal midline theta transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation enhances early consolidation of episodic memory. Npj Sci. Learn. 9, 8 (2024).

Shtoots, L. et al. The effects of theta EEG neurofeedback on the consolidation of spatial memory. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 52, 338–344 (2021).

Rozengurt, R., Shtoots, L., Sheriff, A., Sadka, O. & Levy, D. A. Enhancing early consolidation of human episodic memory by theta EEG neurofeedback. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 145, 165–171 (2017).

Rozengurt, R., Barnea, A., Uchida, S. & Levy, D. A. Theta EEG neurofeedback benefits early consolidation of motor sequence learning. Psychophysiology 53, 965–973 (2016).

Rozengurt, R. et al. Theta EEG neurofeedback promotes early consolidation of real life-like episodic memory. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 23, 1473–1481 (2023).

Reiner, M., Rozengurt, R. & Barnea, A. Better than sleep: Theta neurofeedback training accelerates memory consolidation. Biol. Psychol. 95, 45–53 (2014).

Calderone, D. J., Lakatos, P., Butler, P. D. & Castellanos, F. X. Entrainment of neural oscillations as a modifiable substrate of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 300–309 (2014).

Lakatos, P., Karmos, G., Mehta, A. D., Ulbert, I. & Schroeder, C. E. Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science 320, 110–113 (2008).

Roberts, B. M., Clarke, A., Addante, R. J. & Ranganath, C. Entrainment enhances theta oscillations and improves episodic memory. Cogn. Neurosci. 9, 181–193 (2018).

Moustafa, A. A. Increased hippocampal volume and gene expression following cognitive behavioral therapy in PTSD. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 747 (2013).

Flett, G. L. & Hewitt, P. L. Perfectionism and maladjustment: an overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. In Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment (eds Flett, G. L. & Hewitt, P. L.) 5–31 (American Psychological Association, 2002).

Gibbons, F. X. & Buunk, B. P. Individual differences in social comparison: development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 129–142 (1999).

Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. in Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney, 1–42 (1995).

Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 455–470 (1998).

Neff, K. D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2, 223–250 (2003).

Ebrahimi, A., Samouei, R., Mousavii, S. G., & Bornamanesh, A. R. Development and validation of 26-item dysfunctional attitude scale. APACPH. 5, 101–107 (2013).

Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image Princeton Univ. Press. (1965).

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Turnbull-Donovan, W. & Mikail, S. F. The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale: reliability, validity, and psychometric properties in psychiatric samples. Psychol. Assess. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 3, 464–468 (1991).

Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books (1979).

Bottesi, G. et al. The Italian version of the Depression anxiety stress Scales-21: factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Compr. Psychiatry. 60, 170–181 (2015).

Buuren, S. V. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations. R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

Baccus, J. R., Baldwin, M. W. & Packer, D. J. Increasing implicit self-esteem through classical conditioning. Psychol. Sci. 15, 498–502 (2004).

Garner, D. M. & Garfinkel, P. E. Psychoeducational principles in treatment. In Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders 145–177 (Guilford Press, 1997).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. Remembering Daedalus 144, 53–66. (2015).

Jacobs, J. Hippocampal theta oscillations are slower in humans than in rodents: implications for models of spatial navigation and memory. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130304 (2014).

Antal, A. & Herrmann, C. S. Transcranial Alternating Current and Random Noise Stimulation: Possible mechanisms. Neural Plast. 1–12. (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Joy Ventures Neuro-Wellness Research Grant, to D.A.L., L.S., and G.D. The funder played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A.L., L.S., and G.D. designed the study, provided supervision and wrote the article. A.N. performed the research. A.G. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.D. is the cofounder of GGtude Ltd and has a financial interest in the app described in this paper. Data analyses were conducted by members of the team unaffiliated with GGtude Ltd. All the remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shtoots, L., Nadler, A., Gamoran, A. et al. Evaluating the combined effects of mobile computerized CBT and post-learning oscillatory modulation on self-esteem: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 10934 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83941-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83941-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive Training Via mHealth for Addressing OCD-related Beliefs in Adolescents: A Randomized Pilot Study

Child Psychiatry & Human Development (2026)