Abstract

The catalytic efficiency of sulfonated polystyrene foam waste (SPS) and sulfonated gamma alumina (SGA) in Friedel-Crafts type reactions was compared. All of the materials were studied using the state-of-the-art characterization techniques. SPS was found to carry a higher load of -SO3H functional groups (1.62 mmol H+ per g) compared to SGA (1.23 mmol H+ per g), contributing to its slightly higher efficiency in the regioselective ring-opening of 2-(phenoxymethyl)oxirane with indole. Under mild and solvent-free conditions, SPS catalyzed the reaction of various indoles and oxiranes (9 examples) with acceptable yields (55–99%). The catalyst’s efficiency was further validated in synthesizing various bis(indolyl)methanes (8 examples, 88–99% yield). Recyclability tests confirmed the stability of SPS over multiple cycles, maintaining significant catalytic activity. This study highlights the potential of SPS as a sustainable and efficient catalyst, offering a greener alternative to conventional methods and promoting the valorization of plastic waste in organic synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pursuing sustainable and efficient catalytic processes in organic synthesis is a cornerstone of green chemistry. The evolution of catalysis in organic chemistry has been a journey towards more sustainable and environmentally benign practices. Among the myriad of reactions that organic chemists harness, Friedel-Crafts (FC) type reactions stand out due to their ability to form carbon-carbon bonds, a fundamental step in the synthesis of complex molecules1. The Friedel-Crafts (FC) type reactions are of paramount importance due to their widespread application in the synthesis of aromatic compounds, which are integral to pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and advanced materials2. The traditional approach to FC reactions has predominantly involved the use of homogeneous Bronsted, or Lewis acid catalysts such as AlCl2. However, these catalysts often suffer from drawbacks including corrosiveness, difficulty in separation, and disposal issues, which conflict with the principles of green chemistry3,4.

To address these challenges, researchers have turned their attention to the development of heterogeneous catalysts5. Among these, polymer-supported catalysts have shown considerable promise due to their ease of recovery and potential for reuse6. Functionalization of polystyrene has emerged as a particularly intriguing candidate7. Polystyrene foam, commonly known by its trademarked name, Styrofoam, is a material widely used for packaging and insulation due to its lightweight and insulating properties. However, it poses significant environmental challenges8,9. As a non-biodegradable plastic, polystyrene foam can persist in the environment for centuries, contributing to a growing waste problem. In landfills, it occupies substantial space due to its low density and is resistant to photo-oxidation, making it difficult to recycle10. Currently, Styrofoam recycling is not common in developing countries, and it is not even favored by waste collectors. Moreover, when polystyrene foam breaks down, it releases harmful chemicals like styrene monomers, which are potential carcinogens11,12. Thus, the transformation of polystyrene, a non-biodegradable waste material, into a value-added catalyst aligns with the circular economy model and represents a significant stride in sustainable chemistry13,14,15. A preliminary study investigated the sulfonation of polystyrene by homogeneous and heterogeneous methods. The research aimed to optimize the sulfonation process to enhance the material’s applicability in various reactions16. In another study, researchers have developed ionic strength responsive photonic crystals using partially sulfonated polystyrene opals17. These materials can shift color over the visible range by changing the ion concentration, independent of pH and temperature. This innovation holds promise for environmental monitoring and healthcare screening as ionic strength sensors. SPS has also been applied as a membrane in polymer electrolyte fuel cells. The presence of sulfonate groups in its structure enhances ion conductivity and allows for higher-temperature applications18. The addition of small molecules like benzimidazole to SPS membranes has been shown to improve microstructure and performance. These studies highlight the versatility of SPS in catalyzing Friedel-Crafts type reactions and its potential for functionalization and modification of polystyrene materials. They provide a glimpse into the ongoing research and development in the field of polymer chemistry, particularly in the context of sustainable and green chemical processes. More recent straightforward methods reported for the preparation of sulfonated polystyrene include:

-

1.

Functionalization of syndiotactic polystyrene via superacid-catalyzed Friedel–Crafts alkylation19. This study discussed the functionalization of crystalline syndiotactic polystyrene (sPS) through superacid-catalyzed Friedel–Crafts alkylation. The process involves generating a tertiary carbocation from tertiary alcohols and triflic acid, which then reacts with the aromatic ring of sPS,4.

-

2.

Friedel-Crafts crosslinking methods for polystyrene modification. This research presented a new method for the preparation of sulfonated, crosslinked polystyrene particles. The particles were formed by Friedel-Crafts suspension crosslinking of polystyrene dissolved in nitrobenzene, using a specific crosslinking agent. Sulfonation was achieved in the swollen state, and the particles were analyzed in terms of molecular structure and degree of swelling20.

-

3.

Benzene Ring Crosslinking of a Sulfonated Polystyrene-Grafted SEBS21. In this work, a novel crosslinking strategy via the linkage of carbon atoms on aryl groups by the Friedel–Crafts reaction was proposed for a newly synthesized sulfonated polystyrene-grafted poly(styrene-ethylene/butylene-styrene) block copolymer membrane.

Our study delves into the application of -SO2H functionalized polystyrene foam waste as a solid acid catalyst in FC-type reactions, comparing its performance with that of sulfonated γ-alumina (SGA). The choice of SPS is motivated by its inherent properties: the -SO2H groups provide strong acidic sites that are essential for the catalytic activity in FC reactions. Moreover, the polymeric nature of SPS allows for a high density of these functional groups, thereby enhancing the overall acidity of the material.

The novelty of the work lies in the application of SPS, a material derived from waste, thus adding value to what would otherwise be an environmental pollutant. The promising results obtained not only pave the way for the utilization of SPS in FC reactions but also open avenues for its application in other types of organic transformations.

Experimental

Materials and methods

Solvents and reagents were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and were used as received. FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ALPHA spectrometer in the range of 400 to 4000 cm− 1 using KBr pellets. XRD measurements were performed on a Philips X’pert diffractometer with monochromatized Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 20 mA (Ni filter, 2θ 10 to 70˚ with a step size of 0.05˚ and a count time of 1 s). SEM imaging was performed on a SIGMAVP-500 FESEM (Carl Zeiss Germany). 1H NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker (DRX-500 Avance) and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker (DRX-125 Avance). Chemical shifts of 1H and 13C NMR spectra were expressed in parts per million downfield from TMS. Thermal analyses were performed on a TGD-9800 thermogravimeter from Advance Riko company. Melting points were measured on an Electrothermal engineering apparatus, and are uncorrected. For conductometric titrations, a conductometer made by InoLab was used.

Synthesis of -SO3H functionalized polystyrene (SPS), and sulfonated γ-alumina (SGA)

0.5 g of polystyrene foam waste (expanded polystyrene, Styrofoam) was dissolved in 5.0 mL of dried dichloromethane. Then chlorosulfonic acid (0.5 mL) was added drop-wise and the mixture was stirred under a fume cupboard for 1 h. The mixture was then decanted, and the solid was washed with deionized water (3 × 10 mL). The off-white solid product was oven-dried at 60 °C overnight.

IR (KBr): ν (cm− 1): 3431, 2926, 1631, 1224, 1174, 1060, 1004, 884, 852, 671, 582, 455 cm− 1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C): δ = 1.14 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.98 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.42 (br, 2 H), 4.0 (s, 1H, -SO3H), 6.52 (br, 4 H), 6.75–7.50 (m, 5 H) ppm.

The same procedure was performed to prepare sulfonated γ-alumina (SGA).

IR (KBr): ν (cm− 1): 3436, 1635, 1224, 1154, 1055, 744, 561.

Conductometric titration of SPS and SGA

0.1 g of SPS was dispersed in 10 mL of pre-neutralized methanol in an ultrasonic bath. Then it was titrated with 0.095 M NaOH, and the conductivity of the solution (µS/s) was plotted against the titrant volume (mL) to obtain the equivalent point. The same procedure was used to determine the number of mmols of -SO3H per g of the sulfonated γ-alumina.

General procedure for the Friedel-Crafts type alkylation of indoles with epoxides

To a solution of indole (3.0 mmol) in epoxide (3.0 mmol), 15.0 mg of the catalyst (SPS or SGA) was added and stirred at room temperature for the appropriate time. After completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC, n-Hexane: EtOAc, 10:3), the mixture was filtered and the catalyst was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 3 mL). The combined liquid phase was concentrated in vacuo, and purified by preparative TLC using n-Hexane: EtOAc, 10:3.

General procedure for the Friedel-Crafts type synthesis of bis(indolyl)methanes

To a solution of indole (2.0 mmol) and an aldehyde (1.0 mmol) in EtOH (5.0 mL), 10.0 mg of the catalyst (SPS) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for the appropriate time (obtained by monitoring of the reaction progress by TLC (n-Hexane: EtOAc, 10:3)). The precipitates were then washed with a mixture of water and EtOH (50:50, 3 × 5 mL) and oven-dried at 60 °C. The catalyst was removed from the organic product by treatment with dichloromethane (2 × 3 mL), and the organic product was recrystallized from CH2Cl2.

Selected characterization data for the organic products

1-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol (3a): Solid, m.p. 82–84 °C, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 690, 752, 814, 1037, 1083, 1172, 1244, 1296, 1338, 1427, 1456, 1494, 1595, 2877, 2926, 3056, 3326, 3416, 3545.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.23 (1H, br), 3.15 (1H, dd, J = 14.5, 7.0 Hz), 3.20 (1H, dd, J = 14.5, 6.2 Hz), 4.01 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 6.4 Hz), 4.07 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 3.9 Hz), 4.41 (1H, m), 6.96 (2 H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.02 (1H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.15 (1H, s), 7.18 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.27 (1H, t, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.31–7.36 (2 H, m), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.70 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 8.11 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 29.86, 70.57, 71.59, 111.66, 111.84, 115.06, 119.30, 120.06, 121.50, 122.69, 123.35, 128.03, 129.94, 136.77, 159.09 ppm.

1-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol (3b): Pink solid, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 690, 754, 815, 1039, 1082, 1172, 1240, 1298, 1435, 1460, 1495, 1595, 2873, 2922, 3057, 3292, 3417, 3529.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.40 (3 H, s), 2.50 (1H, br), 3.11 (1H, dd, J = 14.4, 6.6 Hz), 3.15 (1H, dd, J = 14.4, 7.0 Hz), 3.97 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 6.1 Hz), 4.02 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 3.9 Hz), 4.37 (1H, m), 6.96 (2 H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.04 (1H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.15–7.22 (2 H, m), 7.31–7.37 (3 H, m), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.94 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 12.19, 28.89, 70.97, 71.28, 107.29, 110.82, 115.07, 118.46, 119.95, 121.50, 121.67, 129.32, 129.97, 133.13, 135.76, 159.09 ppm.

1-(5-bromo-1H-indol-3-yl)-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol (3c): Solid, m.p. 77–79 °C, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 692, 754, 797, 883, 1041, 1081, 1244, 1296, 1458, 1495, 1595, 2873, 2924, 3062, 3336, 3419.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.40 (1H, br), 3.08 (1H, dd, J = 14.5, 7.0 Hz), 3.13 (1H, dd, J = 14.5, 6.0 Hz), 3.98 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 6.5 Hz), 4.05 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 3.8 Hz), 4.37 (1H, m), 6.96 (2 H, d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.02 (1H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz), 7.27–7.36 (4 H, m), 7.81 (1H, d, J = 1.7 Hz), 8.17 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 29.63, 70.47, 71.45, 111.74, 113.10, 113.36, 115.01, 121.60, 122.02, 124.55, 125.52, 129.81, 129.99, 135.31, 158.94 ppm.

3-(2-hydroxy-3-phenoxypropyl)-1H-indole-5-carbonitrile (3d): Yellow oil, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 692, 754, 812, 1045, 1078, 1244, 1296, 1460, 1495, 1595, 2222, 2879, 2929, 3064, 3285, 3379.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.25 (1H, br), 3.80 (1H, dd, J = 11.4, 5.5 Hz), 3.89 (1H, dd, J = 11.4, 3.7 Hz), 4.08–4.10 (2 H, m), 4.17 (1H, m), 6.96 (2 H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.03 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.27–7.36 (5 H, m), 7.46 (1H, s), 8.06 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 29.58, 69.49, 70.80, 111.82, 112.52, 113.21, 114.92, 121.77, 122.28, 125.27, 125.41, 125.55, 128.12, 130.02, 135.14, 158.77 ppm.

3-(2-hydroxy-3-phenoxypropyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (3e): viscous liquid, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 690, 750, 829, 1197, 1242, 1307, 1458, 1495, 1537, 1595, 1718, 2875, 2925, 3058, 3257, 3334, 3404.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.92 (1H, br), 4.15 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 5.9 Hz), 4.20 (1H, dd, J = 9.4, 4.7 Hz), 4.45 (1H, m), 4.60 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 5.9 Hz), 4.64 (1H, dd, J = 9.3, 4.6 Hz), 6.98 (2 H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.04 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.21 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.32–7.40 (3 H, m), 7.46 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.74 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 9.11 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 66.19, 69.00, 69.18, 109.92, 112.39, 114.97, 121.41, 121.89, 123.14, 126.16, 127.00, 127.81, 130.06, 137.44, 158.68, 162.43 ppm.

1-phenoxy-3-(1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-1-yl)propan-2-ol (3f): White solid, m.p. 224–226 °C, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 694, 731, 757, 912, 1012, 1118, 1174, 1242, 1313, 1361, 1454, 1483, 1492, 1599, 2696, 2765, 2871, 3036, 3064, 3101.

1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD3)2SO, 25 °C): δ = 4.02 (2 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.51–4.59 (2 H, m), 5.05 (1H, dd, J = 12.3, 2.5 Hz), 5.98 (1H, br), 6.59 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.93–6.97 (4 H, m), 7.30 (2 H, t, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.68 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 6.1 Hz), 8.21 (1H, d, J = 7.4 Hz) ppm. 13C NMR (125 MHz, (CD3)2SO, 25 °C): δ = 57.37, 67.82, 71.05, 101.54, 109.44, 115.44, 121.64, 129.99, 130.37, 131.84, 133.05, 144.63, 148.84, 159.31 ppm.

1-butoxy-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propan-2-ol (3 g): Yellow oil, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 742, 812, 1012, 1097, 1230, 1338, 1429, 1458, 1620, 2868, 2929, 2956, 3055, 3334, 3414.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 0.97 (3 H, t, J = 7.3 Hz), 1.45 (2 H, m), 1.63 (2 H, m), 2.46 (1H, br), 3.02 (2 H, d, J = 6.5 Hz), 3.43 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 7.1 Hz), 3.47–3.57 (3 H, m), 4.18 (1H, m), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.17 (1H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.25 (1H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.41 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.68 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 8.13 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 14.40, 19.78, 29.80, 32.20, 70.91, 71.69, 74.68, 111.59, 112.30, 119.37, 119.87, 122.52, 123.18, 128.09, 136.69 ppm.

1-butoxy-3-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)propan-2-ol (3 h): Yellow oil, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 742, 842, 1012, 1114, 1238, 1299, 1436, 1462, 1618, 2867, 2930, 2957, 3055, 3325, 3402, 3544.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 0.97 (3 H, t, J = 7.4 Hz), 1.42 (2 H, m), 1.61 (2 H, m), 2.42 (1H, br), 2.44 (3 H, s), 2.96 (2 H, m), 3.38 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 6.9 Hz), 3.45–3.54 (3 H, m), 4.11 (1H, m), 7.13 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.17 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.31 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.90 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 12.22, 14.41, 19.79, 28.80, 32.24, 71.25, 71.66, 74.40, 107.82, 110.62, 118.53, 119.76, 121.53, 129.37, 132.79, 135.65 ppm.

1-(allyloxy)-3-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)propan-2-ol (3i): Yellow oil, IR (KBr): υ (cm− 1); 742, 829, 926, 1091, 1240, 1299, 1435, 1462, 1491, 1620, 1687, 2858, 2914, 3055, 3336, 3400, 3531.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 2.42 (3 H, s), 2.44 (1H, br), 2.98 (2 H, d, J = 6.9 Hz), 3.43 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 6.7 Hz), 3.52 (1H, dd, J = 9.5, 3.5 Hz), 4.05 (2 H, d, J = 5.6 Hz), 4.15 (1H, m), 5.24 (1H, dd, J = 10.4, 1.2 Hz), 5.33 (1H, dd, J = 17.3, 1.6 Hz), 5.93–6.01 (1H, m), 7.13 (1H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 7.17 (1H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 7.30 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.57 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.95 (1H, br) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C): δ = 12.22, 28.85, 71.30, 72.71, 73.99, 107.66, 110.68, 117.64, 118.51, 119.77, 121.54, 129.33, 132.90, 135.02, 135.68 ppm.

The products 4a-f are very common, and their spectroscopic data can be easily found in the literature.

Results and discussion

In the FTIR spectrum of the sulfonated polystyrene (Supplementary information file, SI, Fig. S1) the following vibrations were observed: acidic O-H stretching: 3431; aliphatic C-H stretching: 2926; C-O-H bending: 1635; phenyl ring C = C: 1450; asymmetric O = S = O stretching: 1224; symmetric O = S = O stretching: 1174; O-S-O bending: 1060 cm− 1.

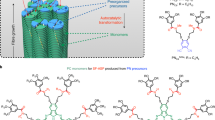

The 1H NMR data of the SPS (SI, Fig. S2), support the partial sulfonation of styrene monomers at the para position (see experimental), as illustrated in Scheme 1. This is in agreement with the results obtained by Coughlin et al.22.

TGA curves for the polystyrene (PS) and SPS are compared in Fig. 1. PS showed a distinct weight loss step at about 430 °C. According to Siregar et al.23, this is mainly due to the degradation of aromatic rings. In comparison, SPS showed a distinct weight loss step of about 25%, in the range of 25 to 140 °C, as a result of dehydration. It should be noted that SPS is very hygroscopic. After a few distinct weight loss steps, up to 700 °C, as a result of the collapse of aliphatic chains, aromatic rings, and -SO3H functional groups, about 10% of ash remained.

To determine the number of mmols of -SO3H functional groups per g of SPS, conductometric titration with NaOH solution was performed. The results showed 1.62 mmol of H+ per g of SPS.

To have a basis for comparison, γ-alumina was also sulfonated in the same manner (Scheme 2) and was characterized accordingly. It should be noted that Wei Lin et al. used 1,2-oxathiolane-2,2-dioxide to prepare SGA, previously24.

Based on the conductometric titration measurements, it was found that each g of γ-alumina adopts 1.23 mmol of H+ as -SO3H. This can be attributed to the limited number of surface hydroxyl groups in the structure of γ-alumina compared to the phenyl rings in the structure of the polymer.

In the FTIR spectrum of the SGA (SI, Fig. S3), the following vibrations were observed: acidic O-H stretching: 3436; Al-O-H bending: 1635; asymmetric O = S = O stretching: 1224; symmetric O = S = O stretching: 1154; O-S-O bending: 1055; Al3+-O2− stretching vibrations in octahedral holes: 850, 744, and 561 cm− 125,26.

TGA analysis of the SGA, on the other hand, did not show a stepwise mass reduction profile (Fig. 2). γ-alumina is one of the main polymorphs of Al2O3 and is stable up to 550 °C, and α-phase is formed beyond 900 ℃, as reported by Marakatti et al.27. Accordingly, the observed profile can be attributed to the removal of adsorbed water molecules on the surface, the condensation of surface hydroxyl groups, and finally the collapse of the -SO3H functional groups (about 13% up to 700 °C).

SEM imaging provided an insightful perspective on the morphology of the structures. Figure 3 depicts the SEM images of γ-alumina (a-c), and sulfonated γ-alumina (d-f) at different magnifications. It can be seen that the rough surface of the γ-alumina particles changes to a relatively smooth surface as a result of functionalization with -SO3H and the hygroscopic nature of the sulfonyl groups.

More evidence of the presence of -SO3H functional groups in the structure of SGA was obtained by EDX analysis. From Fig. 4, it is clear that all of the expected elements (except for H, as EDX is specific to elements with an atomic number higher than 5) showed their K lines at the predicted positions, with 1.2% atomic percent of S, which is nearly in accord with the results of conductometric measurements.

With the characterized catalysts in hand, their potential to catalyze the Friedel-Crafts type reactions was evaluated. First, as a representative example, the regioselective addition of indole to 2-(phenoxymethyl)oxirane was selected to optimize the reaction conditions (Table 1). The ring opening of epoxides is vital in organic synthesis as it produces versatile intermediates, such as β-substituted alcohols, which serve as essential starting materials for the synthesis of various complex and biologically active compounds.

From the data in Table 1, it is clear that protic solvents such as MeOH and EtOH resulted in lower yields, as they may compete with indole for the nucleophilic attack on the epoxide. H2O led to an even poorer result, as the sulfonated surfaces are very hygroscopic. Solvent-free conditions, on the other hand, resulted in better yields, with the best output obtained using 15 mg of the catalyst per mmol of indole. The higher activity of the SPS catalyst compared to SGA may be attributed to its higher load of -SO3H functional groups (1.62 vs. 1.23 mmol of H+ per g of the catalyst). To explore the generality and scope of the reaction, a series of indoles and epoxides were reacted under optimized conditions using SPS as the catalyst. The results, summarized in Table 2, clearly indicate that SPS can be used to prepare a variety of indole-3-yl adducts. Generally, electron-rich indoles resulted in higher yields, and the protocol was tolerant of substituents on the epoxide moiety. However, allyl- or alkyl-substituents on the epoxide led to lower yields. An interesting example is the reaction of 7-azaindole with 2-(phenoxymethyl)oxirane (Table 2, entry 6), which resulted in an excellent yield of the N-alkylated product. These observations support a mechanistic pathway based on the activation of the epoxide ring by H+ sites of the catalyst, followed by nucleophilic attack from the C-3 position of indole, as previously reported26.

Encouraged by these results, we decided to evaluate the potential of SPS in the catalysis of another well-known Friedel-Crafts type reaction, namely, condensation of indoles and aldehydes to produce bis(indolyl)methanes. Bis(indolyl)methanes are important because they possess a wide range of pharmaceutical properties, including anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-proliferative activities26. After optimization experiments, which are summarized in the scheme of the reaction (depicted in Table 3), a series of indoles and aldehydes were tested and provided the desired products in excellent yields.

Generally, electron-rich indoles resulted in shorter reaction times and higher yields, and these are in accord with a mechanistic pathway based on the activation of the aldehyde by -SO3H functional groups, followed by nucleophilic attack from the C-3 position of indole to the carbon of the carbonyl group, as previously reported27.

The stability of a catalyst under the reaction conditions should be approved to ensure that the catalyst remains active over multiple cycles. The SPS catalyst was evaluated for recyclability and reuse in the formation of 3a over five consecutive cycles, yielding 75%, 75%, 73%, 70%, and 67%, respectively. Despite a reasonable decline in activity, the Sheldon test was conducted to assess the catalyst’s heterogeneity. The reaction was halted midway, and the catalyst was filtered out. Following this, the production of 3a stopped, and the recovered catalyst maintained a similar -SO3H content, as determined by conductometric titration (1.60 mmol of H+ per g).

Conclusion

While both SPS and SGA can be used as efficient catalysts in Friedel-Crafts type reactions, our experimental results demonstrated the superiority of SPS over SGA. This is evidenced by higher yields of the organic products under the same conditions. The enhanced performance of SPS can be attributed to its higher degree of acidity, which is crucial for the activation of substrates. The implications of these findings are manifold. From an environmental standpoint, the use of SPS contributes to waste valorization and reduces the reliance on traditional, more hazardous catalysts. From an economic perspective, the low cost and ready availability of polystyrene waste make SPS an attractive option for industrial applications. Furthermore, the operational simplicity of using a solid catalyst streamlines the FC reaction process, making it more amenable to scale-up and continuous flow operations.

In conclusion, the application of -SO2H functionalized polystyrene foam waste as a catalyst in FC-type reactions not only offers a greener alternative to conventional methods but also opens new avenues for the utilization of plastic waste in organic synthesis. This approach is pursued by current research31,32,33,34, . The promising results obtained in this study underscore the potential of SPS to serve as a versatile and sustainable catalyst in a variety of chemical transformations.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Calloway, N. The Friedel-Crafts syntheses. Chem. Rev. 17, 3 (1935).

Sadiq, Z., Iqbal, M., Hussain, E. A. & Naz, S. Friedel-Crafts reactions in aqueous media and their synthetic applications. J. Mol. Liq. 255 (2018)

Sartori, G. & Maggi, R. Use of solid catalysts in Friedel−Crafts acylation reactions. Chem. Rev. 106, 3 (2006).

Anastas, P. & Eghbali, N. Green chemistry: Principles and practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1 (2010).

Lachter, E. R., San Gil, R. A. & Valdivieso, L. G. Friedel Crafts reactions revisited: Some applications in heterogeneous catalysis. Curr. Org. Chem. 28, 14 (2024).

Zong, L., Chen, J., Ren, X., Zhang, G. & Jia, X. Progress in application of organic polymers supported rhodium catalysts in hydroformylation. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40, 8 (2020).

Khokhar, D., Kour, M., Phul, R., Sharma, A. K. & Jadoun, S. Polystyrene-supported Catalysts. In Polymer Supported Organic Catalysts 89–100 (CRC Press, 2024)

Jang, M. et al. Styrofoam debris as a source of hazardous additives for marine organisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 10 (2016).

Turner, A. Foamed polystyrene in the marine environment: Sources, additives, transport, behavior, and impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 17 (2020).

Dennis, R., Dennis, A. & Dennis, W. Styrofoam recycling: Relaxation-densification of EPS by solar heat. J. Sci. Med. 3, 3 (2022).

Kik, K., Bukowska, B. & Sicińska, P. Polystyrene nanoparticles: Sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms. Environ. Pollut. 262 (2020).

Daniels, R. D. & Bertke, S. J. Exposure–response assessment of cancer mortality in styrene-exposed boatbuilders. Occup. Environ. Med. 77, 10 (2020).

El-Tabey, A. E., Mady, A. H., El-Shamy, O. A. & Ragab, A. Sustainable approach: Utilizing modified waste Styrofoam as an eco-friendly catalyst for dual treatment of wastewater. Polymer Bull. 78 (2021)

Mahmoud, M. E., Abdou, A. E. & Ahmed, S. B. Conversion of waste Styrofoam into engineered adsorbents for efficient removal of cadmium, lead and mercury from water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 4, 3 (2016).

Aprilita, N. H., Ofens, T. F. P., Nora, M., Nassir, T. A. & Wahyuni, E. T. Conversion of the Styrofoam waste into a high-capacity and recoverable adsorbent in the removing the toxic Pb2+ from water media. Glob. Nest J. 26, 1 (2024).

Kučera, F. & Jančář, J. Preliminary study of Sulfonation of polystyrene by homogeneous and heterogeneous reaction. Chem. Pap. 50, 4 (1996).

Nucara, L. et al. Ionic strength responsive sulfonated polystyrene opals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 5 (2017).

Lee, J. S. et al. Polymer electrolyte membranes for fuel cells. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 12, 2 (2006).

Jeon, J. Y., Umstead, Z., Kangovi, G. N., Lee, S. & Bae, C. Functionalization of syndiotactic polystyrene via superacid-catalyzed Friedel–Crafts alkylation. Top. Catal. 61 (2018)

Barar, D. G., Staller, K. P. & Peppas, N. A. Friedel-Crafts cross-linking methods for polystyrene modification 3 Preparation and swelling characteristics of cross-linked particles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Product Res. Dev. 22, 2 (1983).

Yan, M. et al. Benzene ring crosslinking of a sulfonated polystyrene-grafted SEBS (S-SEBS-g-PSt) membrane by the Friedel-Crafts reaction for superior desalination performance by pervaporation. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 22 (2022).

Coughlin, J. E., Reisch, A., Markarian, M. Z. & Schlenoff, J. B. Sulfonation of polystyrene: Toward the “ideal” polyelectrolyte. J. Polymer Sci. Part A: Polymer Chem. 51, 11 (2013).

Siregar, J. P., Salit, M. S., Rahman, M. Z. A. & Dahlan Pertanika, K. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calometric (DSC) analysis of pineapple leaf fibre (PALF) reinforced high impact polystyrene (HIPS) composites. J. Sci. Technol. 19, 1 (2011).

Li, W. L., Tian, S. B. & Zhu, F. Sulfonic acid functionalized nano-γ-Al2O3: A new, efficient, and reusable catalyst for synthesis of 3-substituted-2H-1, 4-benzothiazines. Sci. World J. 2013, 1 (2013).

Yoo, K. S., Kim, S. D. & Park, S. B. Sulfation of Al2O3 in flue gas desulfurization by CuO./gamma.-Al2O3 sorbent. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 33, 1786 (1994).

Bedilo, A. F., Shuvarakova, E. I., Rybinskaya, A. A. & Medvedev, D. A. Characterization of electron-donor and electron-acceptor sites on the surface of sulfated alumina using spin probes. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 15779 (2014).

Marakatti, V. S., Mumbaraddi, D., Shanbhag, G. V., Halgeri, A. B. & Maradur, S. P. Molybdenum oxide/γ-alumina: An efficient solid acid catalyst for the synthesis of nopol by Prins reaction. RSC Adv. 5, 93452 (2015).

Tabatabaeian, K., Mamaghani, M., Mahmoodi, N. & Khorshidi, A. Solvent-free, ruthenium-catalyzed, regioselective ring-opening of epoxides, an efficient route to various 3-alkylated indoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 49, 9 (2008).

Singh, A., Kaur, G. & Banerjee, B. Recent developments on the synthesis of biologically significant bis/tris (indolyl) methanes under various reaction conditions: A review. Curr. Org. Chem. 24, 6 (2020).

Tabatabaeian, K., Mamaghani, M., Mahmoodi, N. & Khorshidi, A. Efficient RuIII-catalyzed condensation of indoles and aldehydes or ketones. Can. J. Chem. 84, 11 (2006).

Niakan, M., Masteri-Farahani, M. & Seidi, F. Sulfonated ionic liquid immobilized SBA-16 as an active solid acid catalyst for the synthesis of biofuel precursor 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose. Renew. Energy 50, 212 (2023).

Niakan, M., Masteri-Farahani, M., Seidi, F., Karimi, S. & Shekaari, H. A multi-walled carbon nanotube-supported acidic ionic liquid catalyst for the conversion of biomass-derived saccharides to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. React. Chem. Eng. 8, 2473 (2023).

Niakan, M., Qian, C. & Zhou, S. Highly efficient one-pot conversion of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over acid-base bifunctional MCM-41 mesoporous silica under mild aqueous conditions. Energy Fuels 37, 16639 (2023).

Niakan, M., Qian, C. & Zhou, S. One‐pot, solvent free synthesis of 2,5‐furandicarboxylic acid from deep eutectic mixtures of sugars as mediated by bifunctional catalyst. ChemSusChem e202401930 (2024)

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the Research Council of University of Guilan for their partial support of this study.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. conceptualized and supervised the research and edited the manuscript. B. M. and R. K. performed the experiments and contributed to the preparation of the initial manuscript draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moazzen, B., Kamrouz, R. & Khorshidi, A. Sulfonated polystyrene foam waste as an efficient catalyst for Friedel-Crafts type reactions. Sci Rep 15, 250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83968-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83968-2