Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) imposes a high burden with high mortality and morbidity rates. Early detection of CKD is imperative in preventing the adverse outcomes attributed to the later stages. Therefore, this study aims to utilize machine learning techniques to predict CKD at early stages. This study uses data obtained from a large longitudinal cohort study. The features include patients’ sociodemographic, anthropometric, and laboratory tests that are mostly associated with CKD based on national and international studies. Missing data and outliers were deleted using listwise and interquartile range techniques, respectively. Data initially remained imbalanced to investigate the ability of models to work on imbalanced datasets. Stratified K-folds cross-validation, a robust approach that performs well on imbalanced data, was further performed to enhance the splitting. Interestingly, an interaction was found between age and gender where contrasting data was generated, therefore, to avoid this interaction gender-specific algorithms were developed. Four main algorithms and four algorithms using the stratified K-folds cross-validation technique, consisting of gender-specific Random Forest and feedforward Neural Networks were developed using the preprocessed data of 6855 participants. The RF model in women exhibited the highest AUC of 0.90 followed closely by 0.89 in their NN model. Both models constructed for men yielded an AUC of 0.88. Sensitivity scores were higher in men compared to women. Models demonstrated subpar results regarding specificity, however, the high precision and F1 scores, make the models extremely valuable in a clinical setting to accurately identify CKD cases while minimizing false positive diagnoses. Moreover, the results from stratified K-fold cross-validation indicated that the NN models were more sensitive to the imbalanced dataset and demonstrated a marked increase in performance, particularly specificity, after this approach. These data offer valuable insights for the development of future risk stratification models for CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With a global and national prevalence of 9.5% and 15.1%, respectively, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stands as a serious health problem1,2. Among non-communicable diseases, CKD contributes to a significant rate of morbidities and mortalities, believed to be primarily caused by cardiovascular events in these patients3. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) studies, there has been a prominent increase in the number of deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) attributed to CKD and kidney dysfunction (KD) in 20214,5. This heightened burden is more prominent in lower-income countries4. Moreover, GBD 2019 reports indicated that KD was responsible for about 3.16 million deaths and 76.5 million DALYs around the globe6.

Treatment of CKD once it has reached the end stages is extremely difficult and the disease is often irreversible at those stages7. Moreover, renal replacement therapies and kidney transplants pose massive financial burdens, in addition to their prospective side effects1. Therefore, early detection of CKD may be effective in alleviating the subsequent adverse events following the disease, however, since CKD remains asymptomatic till the late stages early detection is a challenge7. Even though, there is no integrated guideline for screening CKD yet, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) has suggested a precision and individualized approach using patients’ risk factors and their likelihood of developing CKD8. Therefore, the establishment of valid predictive and risk models is the main pillar in CKD management9. Age, history of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity are closely related to CKD10,11. Additionally, smoking and low physical activity have been shown to contribute to the formation, and progression of CKD evidenced by lower GFR, higher proteinuria, and lower post-kidney transplant survival rates12,13. Moreover, cohort studies and risk models have found that patients with chronic exposure to acute phase reactants like human C-reactive protein (CRP) and pro-inflammatory factors like Uric Acid are at greater risk of renal impairment10,14. Implementing practical predictive models using these factors may help in screening high-risk patients in clinical settings.

Machine learning (ML) algorithms offer robust predictive models and have attracted massive attention in the field of chronic diseases. ML predictive models have exhibited the potential to enhance the quality of screening methods, diagnosis accuracy, and overall clinical decision-making in chronic non-communicable diseases15. Supervised classification ML models leverage the information gained from a given dataset to predict the outcome of interest16. Despite efforts made to employ these models in chronic kidney disease prediction, a generalizable conclusion has yet to be drawn from the results16. To fill this gap, this study aims to investigate practical predictive factors for early CKD detection by utilizing Random Forest (RF) and Neural Network (NN) algorithms in a large population in Iran.

Materials and methods

Study population

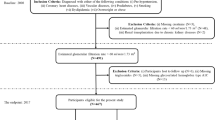

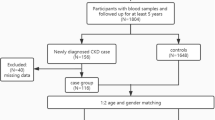

This study was conducted using the Mashhad Stroke and Heart Atherosclerotic Disorders (MASHAD) Study database. The MASHAD cohort study was initiated in 2010 using a stratified cluster random sampling technique in three regions of Mashhad. The details of the study’s methodology are discussed elsewhere17. The original database consisted of information on 9704 participants. Figure 1 shows the workflow and a schematic description of the study subjects.

Anthropometric assessments

Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were evaluated according to the standard measurement techniques18. Height (cm) was measured with a tape measure to the nearest 0.01 mm. Weight (kg) was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using electronic scales. BMI was calculated using the participants’ weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2).

Laboratory evaluation

All participants were advised to undergo 14 h overnight fasting and the blood samples were obtained in the following morning. To keep the study coherent all samples were evaluated in the same laboratory17. BT3000 biochemical analyzer was used for evaluating the following parameters: fasting blood glucose (FBG), Uric Acid (UA), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs CRP), Lowdensity lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol (TC), Triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and creatinine (Cr). Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) was assigned based on WHO definitions as FBG ≥ 126 mg/dl or in participants receiving oral hypoglycemic or insulin treatment17,19.

Blood pressure assessment

Systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressures were measured by standard mercury sphygmomanometers. Hypertension (HTN) was defined and reported following WHO guidelines as an SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or a DBP ≥ 90 mmHg or in participants being on anti-hypertensive medication17,20.

Assessment of physical activity

Physical activity level (PAL) was assessed based on questionaries evaluating activities during work hours, off time, and in bed21. The questionnaire filled by participants was in accordance with the James and Schofield human energy requirements equations21.

Assessment of other variables

Demographic, social, and medical history features including age, gender, smoking status, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) history were recorded by healthcare professionals and a nurse interview.

Feature selection and target assignment

For the purposes of this study, participants’ demographic and anthropometric information including age, gender, and BMI were extracted from the database. Data obtained regarding medical and social history included a history of HTN, DM, CVD, smoking, and PAL, respectively. Laboratory data used for this study included Cr (mg/dL), hs.CRP (mg/L), FBG (mmol/L), and uric acid (mg/dL). The features used for model development in this study were decided after a thorough investigation of pivotal factors demonstrated in the KDIGO guidelines11, national CKD burden study22, and availability of data in our dataset.

The Kidney Disease Quality Outcome Initiative’s (KDOQI) definition, defines CKD as GFR below 60 for more than 3 months without regard for the underlying cause23. Following this initiative, this study used a GFR cut-off of 60 (mL/min/1.73 m2) to evaluate whether the participants have chronic kidney diseases or not. The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation has shown superior results in terms of accuracy compared with other methods in assessing the Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)24. Therefore, the MDRD equation was used for calculating GFR using participants’ age, gender, and creatinine levels.

Data preprocessing

We used a one-hot coding approach for categorical variables including gender, HTN, DM, CVD, smoking status, and CKD status. Missing data imputation was implemented using the list-wise deletion technique. Afterward, outliers were detected with the interquartile (IQR) technique and removed.

Initially, despite our dataset being highly imbalanced, we opted for not performing over- or under-sampling techniques on the dataset to investigate whether the models perform well in an unbalanced dataset. Subsequently, for the neural network algorithms, data were normalized and standardized with scaling and centering approaches. Lastly, the dataset was split into training and testing sets with 75% and 25% allocations, respectively.

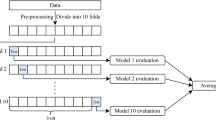

To reduce the possible bias induced by our imbalanced dataset, we opted for a splitting method that offers a robust performance on imbalanced data. Therefore, stratified K-fold cross-validation was employed. Stratified K-fold cross-validation is a robust method that maintains the proportion of each class (folds) similar to the whole dataset, thereby preserving class distribution and offering a more enhanced approach for unequal data distributions25. Thus, stratified K-fold cross-validation with 10 folds (K = 10) was performed in this study.

Random forest model

Random Forest is a complex ensemble learning model based on a multitude of regression trees. This supervised machine learning algorithm uses a similar node splitting criteria (Information Gain, Gini Index, Entropy) with the Decision Tree model26. However, unlike Decision Tree, RF benefits from Bootstrap Aggregation (Bagging) and Feature Randomness, which means that RF uses a random subset of the training data for each tree and a random subset of the features at each split26. The final decision in RF is reached by an accumulative prediction of the average values of all individual trees. These differences allow RF to provide more robust and generalizable data by avoiding overfitting. We used the Gini index criteria for node splitting and 500 trees to construct the forest. After the model construction, features were demonstrated as the most important to least, and partial dependency and ROC curve plots were obtained.

The Gini Index equation is described below:

C: number of classes,

p(i): The probability of picking the data point with the class i.

Neural network model

Artificial neural networks are computational models resembling neurotransmission in the human brain with a complex structure consisting of predictors as inputs, hidden layers, and their processors (neurons), and the outcome variables as the final output27. Inputs are weighted randomly prior to “learning” and then the weighted sum of the inputs, presented to the hidden layer, is used to measure the strengths of the output. Owing to their unique ability to learn, NNs are capable of processing more complex patterns. Learning is defined as the repeated adjustment of weights based on measured output and the training set output27. This study used a feed-forward back propagation neural network model with a sigmoid activation function. This approach allows the network to form nodal connections without making any loops28.

Hyperparameters of the RF and NN models are demonstrated in Table 1.

Model evaluation

Assessment of the model’s performance was carried out using the accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, precision, F1 score, and Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve (ROC curve AUC) for all models.

Precision: True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives).

Sensitivity: True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives).

Specificity: True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives).

F1 score: 2 * (Precision * Sensitivity) / (Precision + Sensitivity).

Model interpretation

The Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) algorithms are widely used for providing understandable explanations for ML predictions25. Therefore, LIME algorithms were implemented to enhance the understandability and interpretability of the outcomes.

Statistical analysis

In this study the quantitative results were stated as mean and standard deviation and the qualitative results as frequency and percentage. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the data. Based on normality Independent T-test or Mann-Whitney test was employed to compare quantitative data. The chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variables. Descriptive and inferential analysis and data preprocessing were performed in SPSS version 27. Model development and hyperparameter tuning were performed using R programming software 4.3.2 “randomForest” and “neuralnet” packages.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all MASHAD study participants. This study was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Results

Cohort characteristics

Estimated GFR values were computed for 8155 adult participants with an average age of 58.69 ± 9.03 in men and 57.04 ± 8.70 in women, out of whom 6372 (78.13%) individuals had GFR rates equal to or over 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, while the remaining 1783 (21.86%) GFR values fell below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Table 2 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the dataset by CKD status. Average age, PAL, UA, and FBG levels were significantly higher among the CKD-positive group, conversely, the BMI and hs.CRP values were lower. After the dataset was processed for the selected features, 258 missing variables and 1042 outlier values were excluded, and the models were developed on a dataset comprising 6855 participants.

Adjustment of models based on feature interactions

Interestingly, an interaction between age and gender was observed regarding their impact on the incidence of CKD. Consequently, a detailed analysis of the results from both RF and NN models was conducted, in which BMI was identified as a protective factor against kidney failure. Furthermore, it was discovered that this protective effect occurred due to the mentioned interaction. Therefore, the results of the two models were analyzed separately by gender and age to adequately address this interaction effect.

In that regard, since menopause is a known contributor to CKD in women29, we used the population of women above the age of 50 for model development.

Since NN models were aimed to be performed for men and women separately, the hidden layers and neurons were developed for each gender separately, and 2 hidden layers with (7,3) and (5,3) neurons, were implemented for men and women, respectively.

Model performance

The accuracy of all models was high with 86.34% and 84.58% for RF and NN models in women and 89.07% and 84.84% for men respectively. Sensitivity scores were higher in men with 95.48% and 90.52% for RF and NN compared to 92.26% and 88.44% in women. RF models in both men and women yielded moderate specificity values (53.57%), while the NN models demonstrated higher specificity in both genders (68.29% and 72.73% in women and men respectively).

To further assess the feasibility of models in clinical practice precision and F1-score were also evaluated. The precision (women: RF 91.66%, NN 92.16%, men: RF 91.92%, NN 87.61%) and F1-score (women: RF 91.96%, NN 87.92%, men: RF 93.63%, NN 89.04%) were high in all models. When comparing the two genders, precision was slightly higher in the NN model for women, and the F1 scores were higher in both models attributed to men. Table 3 summarizes the performance metrics of all models.

The receiver operation characteristic (ROC) curve and the associated area under the curve (AUC) of the models are demonstrated in Fig. 2. The RF model in women exhibited the highest AUC of 0.90 followed closely by 0.89 in their NN model. Both models constructed for men yielded an AUC of 0.88.

Implementation of stratified K-fold cross-validation demonstrated enhanced performance in all aspects in the NN models of both men and women, whereas it did not offer higher performance ability for RF models, except for a consistent increase in sensitivity for both men and women (Table 3).

Variable importance and interpretation of models

The importance of each feature and data on how various features influenced the outcomes were evaluated and the data are presented as Supplementary Figures S1-S7. The importance of the factors influencing the risk models differed between the RF (Supplementary Figures S1, S2) and NN (Supplementary Figures S3, S4) models. The RF model in women recognized BMI, age, PAL, UA, hs.CRP and FBG were the most important features, whereas although the features were the same in men, they differed in order: BMI, UA, age, PAL, hs.CRP, and FBG. The remaining variables including a history of DM, HTN, CVD, and smoking were reportedly the least important. Supplementary Figures S5 and S6 display the partial dependency plots of the important features in RF.

While BMI was still the most prominent feature in the NN models, categorical variables like HTN, DM, and gender played more important roles in NN models with BMI, FBG, gender, DM, HTN, and BMI, HTN, FBG, gender, DM being the important feature in women and men respectively.

Discussion

Unlike the development of CKD into ESRD, the detection of CKD at the initial stages has yet to yield concise prediction criteria. This study utilized random forest and artificial neural network machine learning algorithms to create risk prediction models for the presence of CKD evidenced by eGFR levels below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Furthermore, taking into consideration that CKD is found to be more prevalent in women at peri- and post-menopause ages compared to younger women29, we trained and tested our models separately for women above 50 and men to ensure more clinically accurate results. All 4 models developed for men and women demonstrated high accuracy (over 80% in all models). Nevertheless, accuracy is not a suitable metric for evaluation in an imbalanced dataset as the class dominating the data will automatically influence the prediction. Therefore, more attention should be directed toward other performance metrics when interpreting our results. Sensitivity, precision, F1-score, and AUC were high in all models. However, models demonstrated subpar results regarding specificity with 53.57% in both RF models, 68.29%, and 72.73% in NN models for women and men respectively. The high precision and F1 scores, make the models extremely valuable in a clinical setting due to their innate ability to accurately identify CKD cases while minimizing false positive diagnoses. Our study also employed stratified K-fold cross-validation to investigate CKD prediction. The results further indicated that RF was a more robust approach for our imbalanced dataset, however, the stratified K-fold cross-validation in NN models demonstrated better outcomes and particularly higher specificity (83.01% for women and 89.49% for men). These data indicate that the NN models were more impacted by the imbalanced data compared to RF models.

In two studies using the University of California Irvine (UCI) dataset, RF and NN models have proved superior in CKD prediction compared to other supervised learning systems30,31. The studies implemented the recursive feature elimination (RFE) technique and successfully gained 100% accuracy and sensitivity in RF30and an AUC of 1.0 for NN31with Hb, Rbc, Packed Cell Volume, Alb, SG, HTN, and blood Urea as the most influencing features. Despite the very promising results, the relatively small sample size inhibits the findings from being generalizable in real-world clinical settings. When compared in a large dataset of 134,895 individuals in Korea, the auto-encoder neural network model demonstrated better CKD classification ability compared to RF with the highest sensitivity and specificity at stage 1 (99.76%, 99.79%)32. The auto-encoder NN is a derivate of the neural network, integrating unsupervised and supervised learning methods, and has the same nodes at the output as the input32. Despite random forest’s relatively lower sensitivity at classifying higher stages of CKD, it significantly excelled in the first two stages with 0.99 sensitivity32. The features utilized in Jeong et al.’s study differed from ours with a higher number of laboratory data focusing on liver function, and lipid profile32. When comparing the results of various ML models in CKD, it is crucial to bear the racial and ethnic variances in mind as they play a significant role in CKD development, prevalence, and risk factors33,34. Hence, developing nation-based CKD predictive models is of immense importance. To our knowledge, no study has yet proposed an ML model to predict the incidence of CKD at early stages in the Iranian population.

High BMI is associated with deterioration of kidney function35, and based on the Framingham Heart Study, obesity, defined as BMI over 30, is a predictor of CKD in patients with no prior history of chronic kidney disease36. Additionally, new onset al.buminuria is more prominently observed in obesity37. The exact mechanism underlying the influence of obesity and weight gain in promoting renal dysfunction remains unknown. However, it is believed that when faced with obesity, kidneys instruct a compensatory hyperfiltration to meet the elevated metabolic demand, damaging the glomerular filtration barrier, and leading to glomerular hyper-permeability (36). Agreeing with this notion, BMI is the most influential factor in predicting CKD in our proposed models.

An interesting finding in this study is that the RF partial dependency plots in men demonstrated higher CKD prediction in men with BMI below 20 kg/m2 rather than those with obesity, whereas in women the model was able to acceptably predict CKD in both lean, overweight, and obese values of BMI, albeit with more steep slopes in the overweight and an overall better predictive performance in BMI below 20 kg/m2. Therefore, it can be concluded that weight has a paradoxical effect on CKD. This hypothesis is supported by several studies where lower BMI values were significantly associated with higher mortality rates and adverse renal events38,39. Further, BMI-stratified studies are needed to discover the exact relationship between BMI values and CKD incidence.

Despite the imperative role of obesity in predicting CKD, few studies have investigated BMI in their risk models. In a large prediction study conducted on the Taiwanese population, BMI was not observed as one of the foremost factors contributing to CKD40. In addition to their different ML models from our study, ethnic and behavioral differences may be of cause. This hypothesis is further confirmed by the higher burden of CKD in Iran compared to other countries globally22, which is most likely attributed to the higher incidence of CKD risk factors like obesity41.

Aging has widely been associated with diminished kidney function42. There is a decline in GFR values as age increases, ascribed to the inherent age-related physiologic changes in renal mass, cardiac output, and the vasoconstriction-dilation balance42. Age was among the most influential factors in our models. Consistent with our results, the large-scale study by Aoki et al., which investigated the predictive ability of a random forest model in assessing the GFR decline of over 30% over 5 years, demonstrated aging as an important factor influencing the model’s high performance (AUC 0.85).

Hyperuricemia, described as serum UA levels exceeding 7 mg/dL in men and 6 mg/dL in women, is a prominent contributing factor in the development of new-onset CKD and its progression owing to the deposition of UA in the renal collecting tubes, and changes in the renal endothelium43,44. In addition to gout, asymptomatic hyperuricemia also promotes renal dysfunction and CKD43. The findings of this study, in consistency with a previous study of CKD ML models40, identified serum UA levels as one of the most important indicators of the predictive models. Interestingly, our findings suggested that serum UA levels can predict CKD beyond the hyperuricemia definition. Estimated UA levels below 4 mg/dL and over 7 mg/dL in men, and UA levels over 5 mg/dL in women were indicative of CKD incidence. Similar to our results, a retrospective cohort study by Nakayama et al. with 138,511 participants demonstrated that serum UA levels below 4 mg/dL and over 10 mg/dL in men and UA levels below 4 mg/dL and over 7 mg/dL in women showed a more significant risk of CKD incidence or proteinuria in the male population45. The precise cut-off levels of low and high UA in men and women differ between studies45,46, leaving room for further investigations. Variances in hormonal levels between the two genders further, necessitate the evaluation of the two genders and menopausal women separately47.

A discrepancy was observed in our results regarding the important features in NN models compared to RF models. Although BMI and FBG were common between the models, conventional predictors of CKD like HTN and DM were of more importance in predicting CKD in the neural network. Age, UA, and PAL did not hold high importance in the NN models. When interpreting the important features of the models, it is noteworthy to bear in mind that while NN models are great in providing predictive insights, these models are less reliable in providing important features. This discrepancy is set in the key differences in the process of these models. Random Forest, owing to its ensemble method, is a robust method to determine the key variables contributing to the outcome and does so by evaluating the impact of each variable in decreasing the impurity of each tree node. Moreover, NN models were more sensitive to the imbalanced dataset and therefore offered more robust outcomes after the application of stratified K-fold cross-validation. These data offer insight for the development of future risk stratification models derived from large clinical datasets.

The findings of this study are supported by the large number of participants, in-depth and gender-specific analysis, and high performance of the models. The robust sensitivity, precision, and F1 scores indicate the practicality of our models for the means of screening. Even though the features utilized in this study are cost-benefit, this study did not incorporate important laboratory variables including albumin and urine protein levels. Although these variables could potentially add complexity to the models, the inclusion of these elements can increase the accuracy of the results.

Conclusion

This study presents robust risk models for predicting the incidence of CKD in the Iranian population. With high sensitivity, precision, and F1-score, the models provide an in-depth prediction of CKD in the general population. The robust performance coupled with their cost-effective features indicates that the models may serve as valuable and practical screening tools in the general Iranian population.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Jadoul, M., Aoun, M., Masimango, M. & Imani The major global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet Glob Health. 12 (3), e342–e343 (2024).

Bouya, S. et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney Disease in Iranian General Population: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ther. Apher Dial. 22 (6), 594–599 (2018).

Vondenhoff, S., Schunk, S. J. & Noels, H. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Herz 49 (2), 95–104 (2024).

Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet, 403(10440): pp. 2162–2203. (2024).

Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet, 403(10440): pp. 2100–2132. (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of kidney dysfunction from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public. Health. 23 (1), 1218 (2023).

Levin, A. et al. Perspectives on early detection of chronic kidney disease: the facts, the questions, and a proposed framework for 2023 and beyond. Kidney Int. 103 (6), 1004–1008 (2023).

Shlipak, M. G. et al. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 99 (1), 34–47 (2021).

Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B. & Kengne, A. P. Risk models to predict chronic kidney disease and its progression: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 9 (11), e1001344 (2012).

Kawasoe, S. et al. Development of a risk prediction score and equation for chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 5001 (2023).

Stevens, P. E. et al. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 105 (4), S117–S314 (2024).

Lang, S. M. & Schiffl, H. Smoking status, cadmium, and chronic kidney disease. Ren. Replace. Therapy. 10 (1), 17 (2024).

Robinson-Cohen, C. et al. Physical activity and change in estimated GFR among persons with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25 (2), 399–406 (2014).

Gao, J. et al. The cumulative exposure to high-sensitivity C-Reactive protein predicts the risk of chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 45 (1), 84–94 (2019).

Delpino, F. M. et al. Machine learning for predicting chronic diseases: a systematic review. Public. Health. 205, 14–25 (2022).

Rashid, J. et al. An augmented Artificial Intelligence Approach for Chronic diseases Prediction. Front. Public. Health, 10. (2022).

Ghayour-Mobarhan, M. et al. Mashhad stroke and heart atherosclerotic disorder (MASHAD) study: design, baseline characteristics and 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation. Int. J. Public. Health. 60 (5), 561–572 (2015).

Norton, K. I. Standards for Anthropometry Assessment, in Kinanthropometry and Exercise Physiologyp. 68–137 (Routledge, 2018).

World Health, O. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus (World health organization, 1999).

World Health, O. & International Society of Hypertension Writing. and G., World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertension. Journal of hypertension, 2003. 21(11): pp. 1983–1992. (2003).

Gerrior, S., Juan, W. & Basiotis, P. An easy approach to calculating estimated energy requirements. Prev. Chronic Dis. 3 (4), A129 (2006).

Nejadghaderi, S. A. et al. Trends of national and sub-national burden attributed to kidney dysfunction risk factor in Iran: 1990–2019. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14. (2023).

Levey, A. S. et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 67 (6), 2089–2100 (2005).

Tarwater, K. Estimated glomerular filtration rate explained. Mo Med. 108 (1), 29–32 (2011).

Widodo, S., Brawijaya, H. & Samudi, S. Stratified K-fold cross validation optimization on machine learning for prediction. Sinkron: jurnal dan penelitian teknik informatika, 6(4): pp. 2407–2414. (2022).

Biau, G. & Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 25, 197–227 (2016).

Myers, J. et al. A neural network approach to predicting outcomes in heart failure using cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Int. J. Cardiol. 171 (2), 265–269 (2014).

Sazlı, M. H. A brief review of feed-forward neural networks. Communications Faculty of Sciences University of Ankara Series A2-A3. Phys. Sci. Eng., 50(01). (2006).

Dines, V. A. & Garovic, V. D. Menopause and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20 (1), 4–5 (2024).

Senan, E. M. et al. Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease Using Effective Classification Algorithms and Recursive Feature Elimination Techniques. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2021. (2021).

Singh, V., Asari, V. K. & Rajasekaran, R. A Deep Neural Network for Early Detection and prediction of chronic kidney disease. Diagnostics, 12. (2022).

Jeong, B. et al. Comparison between statistical models and machine learning methods on classification for highly imbalanced multiclass kidney data. Diagnostics 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10060415 (2020).

Choi, Y. et al. Racial differences and Contributory Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular risk factors towards chronic kidney Disease Progression. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 19, 433–445 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for CKD: a comparison between the adult populations in China and the United States. Kidney Int. Rep. 3 (5), 1135–1143 (2018).

Herrington, W. G. et al. Body-mass index and risk of advanced chronic kidney disease: prospective analyses from a primary care cohort of 1.4 million adults in England. PLoS One. 12 (3), e0173515 (2017).

Ting, S. M. S. et al. Overweight, obesity and chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin. Pract. 112 (3), c121–c127 (2009).

Garofalo, C. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggests obesity predicts onset of chronic kidney disease in the general population. Kidney Int. 91 (5), 1224–1235 (2017).

Ouyang, Y. et al. Underweight is an independent risk factor for renal function deterioration in patients with IgA nephropathy. PLoS One. 11 (9), e0162044 (2016).

Ricardo, A. C. et al. Healthy lifestyle and risk of kidney disease progression, atherosclerotic events, and death in CKD: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 65 (3), 412–424 (2015).

Chiu, Y. L. et al. Health data-driven machine learning algorithms applied to risk indicators assessment for chronic kidney disease. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy, : pp. 4401–4412. (2021).

Djalalinia, S. et al. Patterns of obesity and overweight in the Iranian Population: findings of STEPs 2016. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 42 (2020).

Weinstein, J. R. & Anderson, S. The aging kidney: physiological changes. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 17 (4), 302–307 (2010).

Li, L. et al. Is hyperuricemia an independent risk factor for new-onset chronic kidney disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis based on observational cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 15 (1), 122 (2014).

Gherghina, M. E. et al. Uric acid and oxidative stress—relationship with Cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal impairment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23063188 (2022).

Nakayama, S. et al. Detailed association between serum uric acid levels and the incidence of chronic kidney disease stratified by sex in middle-aged adults. Atherosclerosis 330, 107–113 (2021).

Mori, K. et al. U-shaped relationship between serum uric acid level and decline in renal function during a 10-year period in female subjects: BOREAS-CKD2. Hypertens. Res. 44 (1), 107–116 (2021).

Li, G. et al. The dose-response relationship between sex hormones and hyperuricemia in different gender: NHANES 2013–2016. (2022). Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13 .

Funding

The collecting of clinical data was financially supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. MA, MGM, and HE contributed to the Study concept and design. MA, MGM, and HE contributed to methodology of the projects and supervised the project. PBT and DT contributed to analyzing and interpreting the data and drafted the manuscript. MGM, and HE critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahrami, P., Tanbakuchi, D., Afzalaghaee, M. et al. Development of risk models for early detection and prediction of chronic kidney disease in clinical settings. Sci Rep 14, 32136 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83973-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83973-5