Abstract

Frailty and fractures are closely associated with adverse clinical outcomes. This retrospective study investigated the prognostic impact of frailty, prevalent fractures, and the coexistence of both in patients with cirrhosis. Frailty was defined according to the Fried frailty phenotype criteria: weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and low physical activity. Prevalent fractures were assessed using questionnaires and lateral thoracolumbar spine radiographs. Cumulative survival rates were compared between the frailty and non-frailty groups, fracture and non-fracture groups, and all four groups stratified by the presence or absence of frailty and/or prevalent fractures. Among 189 patients with cirrhosis, 70 (37.0%) and 74 (39.2%) had frailty and prevalent fractures, respectively. The median observation period was 64.4 (38.6–71.7) months, during which 50 (26.5%) liver disease-related deaths occurred. Multivariate analysis identified frailty and prevalent fractures as significant independent prognostic factors in the overall cohort (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively). The cumulative survival rates were lower in the frailty or fracture groups than in the non-frailty or non-fracture groups, respectively, in the overall cohort and in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Patients with both frailty and prevalent fractures showed the lowest cumulative survival rates, whereas those without these comorbidities showed the highest cumulative survival rates among the four stratified groups. Frailty and prevalent fractures were independently associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Additionally, the coexistence of both comorbidities worsened the prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frailty, as defined by increased vulnerability to health stressors due to the depletion of multiple physiological reserves, is a common and serious comorbidity in patients with cirrhosis1,2. Factors including malnutrition, cirrhosis-specific factors (hyperammonemia; reduced insulin-like growth factor [IGF-1], branched-chain amino acids, and vitamin D levels; and dysfunctional protein synthesis), physical inactivity, osteosarcopenia, chronic inflammation (elevated serum inflammatory cytokine levels and immune system dysfunction), and dysbiosis, are implicated in the development and progression of frailty1,2,3,4,5. A meta-analysis of 12 studies revealed that the pooled prevalence of frailty was 29% in patients with cirrhosis6. Furthermore, frailty was identified as a risk factor for reduced quality of life, hospitalization, cirrhosis progression, cirrhosis-related events (e.g., ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and infection), and mortality7,8,9,10,11,12,13.

Osteoporosis, a systemic skeletal disease characterized by bone mass loss and bone microarchitecture deterioration, is another frequent musculoskeletal comorbidity in patients with cirrhosis14. Similar to frailty pathogenesis, malnutrition, reduced IGF-1 and vitamin D levels, physical inactivity, sarcopenia, and imbalanced ratio of osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand due to chronic inflammation dysregulate bone remodeling, resulting in the loss of bone mass14,15.

A meta-analysis of six studies reported a significantly higher prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with cirrhosis compared to controls (odds ratio [OR], 2.52)16. Furthermore, survival rates were significantly lower in patients with osteoporosis than in those without17. In patients with cirrhosis, increased levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) cause bone quality deterioration18, which together with osteoporosis exacerbates the reduction in bone strength, thereby increasing fracture risk18,19. A meta-analysis of eight studies found that patients with cirrhosis had an increased risk of any fracture, hip fracture, spine/trunk fracture, and limb fracture (OR: 1.94, 2.11, 2.00, and 1.82, respectively)20. Furthermore, patients with cirrhosis or primary biliary cholangitis had a higher incidence of fractures and post-fracture complications (e.g., infection, acute renal failure, and peptic ulcer) and higher 30-day and 1-year mortality rates compared with control subjects21,22,23,24. However, the relationship between fractures and the long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis remains inconclusive.

Frailty increases the risk of recurrent falls, subsequent fractures, fracture-related hospitalizations, and mortality in older adults25,26,27,28. Conversely, fractures increase the risk of new fractures, reduced physical performance due to pain, frailty, and mortality29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Thus, the close relationship that exists between frailty and fractures can become a vicious cycle, ultimately increasing the risk of mortality. Meanwhile, in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD), frailty has been reported to be associated with low bone mineral density (BMD), osteosarcopenia, vertebral fractures, and mortality1,10,11,12,13. However, in addition to the close association between fractures and prognosis, it is unclear whether the coexistence of frailty and fractures worsens the patient’s prognosis. To clarify the abovementioned relationships, we investigated the impact of frailty, prevalent fractures (symptomatic and asymptomatic), and the coexistence of both conditions on the long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis.

Results

Study population and characteristics

Supplementary Fig. S1 presents a flow diagram of the patient screening process employed in this study. Of the 203 patients with cirrhosis who were initially evaluated for eligibility, 14 met the exclusion criteria, leaving a final enrolled cohort of 189 patients. The baseline characteristics of these participants are summarized in Table 1. This study cohort consisted of 121 men and 68 women, with a median age of 70.0 (59.0–77.5) years. The median Child–Pugh (CP) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores were 6 (5–7) and 8 (7–11), respectively. The rates of decompensated cirrhosis, osteoporosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were 33.9% (64/189), 32.3% (61/189), and 13.8% (26/189), respectively.

Clinical characteristics of the frailty and non-frailty groups

The prevalence of frailty was 37.0% (70/189; Table 1). The frailty group was significantly older (p < 0.001) and demonstrated significantly higher CP scores (p = 0.035) and lower albumin levels (p = 0.043) than the non-frailty group. Additionally, the former had significantly higher prevalence of decompensated cirrhosis (p = 0.008) and osteoporosis (p < 0.001) than the latter. Notably, the rate of prevalent fractures was significantly higher in the frailty group than in the non-frailty group (60.0 vs. 26.9%; p < 0.001; Fig. 1A).

Clinical characteristics of the fracture and non-fracture groups

As shown in Table 2, prevalent fractures were present in 74 (39.2%) patients (vertebra, n = 56 [symptomatic, n = 27; asymptomatic, n = 29]; rib, n = 9; proximal femur, n = 7; distal radius, n = 6; lower extremity, n = 6; proximal humerus, n = 5; and pelvis, n = 3). The fracture group was significantly older and had significantly higher prevalence of osteoporosis than the non-fracture group (p < 0.001 for both). Notably, the prevalence of frailty (56.8 vs. 24.3%) and the median frailty score (3 vs. 1) were significantly higher in the fracture group than in the non-fracture group (p < 0.001 for both; Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting a close association between frailty and fractures.

Prognostic impact of frailty and fractures

The median follow-up period was 64.4 (38.6–71.7) months, during which 50 (26.5%) liver disease-related deaths occurred (liver failure, n = 28; HCC, n = 12; rupture of esophageal varices, n = 8; and liver transplantation, n = 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). The frailty group had significantly lower cumulative survival rates than the non-frailty group (p < 0.001; Fig. 2A), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates of 98.6%, 64.7%, and 51.3% in the frailty group and 99.2%, 93.9%, and 87.1% in the non-frailty group, respectively. Similarly, the cumulative survival rates were significantly lower in the fracture group than in the non-fracture group (p < 0.001; Fig. 2B), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates of 98.6%, 71.0%, and 58.6% in the fracture group, and 99.1%, 90.9%, and 84.0% in the non-fracture group, respectively. We then categorized all fractures into symptomatic and asymptomatic (all of the asymptomatic fractures were vertebral fractures) and estimated the cumulative survival rates (Fig. 3). Similar to patients with symptomatic fractures, the cumulative survival rates in patients with asymptomatic fractures were significantly lower than those in patients without fractures (p = 0.041). Even when limited to vertebral fractures, the cumulative survival rates in patients with asymptomatic fractures were comparable to those in patients with symptomatic fractures (p = 1.000; Supplementary Fig. S3). We further compared cumulative survival rates according to the number of fracture sites (one site vs. two or more sites [including multiple vertebral fractures]; Supplementary Fig. S4). The latter had significantly lower cumulative survival rates than the former (p = 0.039).

There were 14 non-liver-related deaths that were considered censored (Supplementary Table S1). Even when these censored patients were included in the analysis of the endpoint cases (i.e., including all-cause mortality), the results were identical to those described above: i.e., the frailty or fracture group had significantly lower cumulative survival rates than the non-frailty or non-fracture group, respectively (p < 0.001 for both; Supplementary Fig. S5A,B).

Prognostic impact of frailty and fractures in subgroups

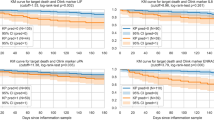

We compared the cumulative survival rates between the frailty and non-frailty subgroups and the fracture and non-fracture subgroups in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. In patients with compensated cirrhosis, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 100 vs. 100%, 88.5 vs. 96.5%, and 82.0 vs. 91.2% in the frailty and non-frailty groups, respectively (Fig. 4A). The cumulative survival rates in the frailty group were lower than those in the non-frailty group, although the difference was marginally significant (p = 0.061). Meanwhile, the fracture group had significantly lower cumulative survival rates than the non-fracture group (p = 0.003), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates of 100 vs. 100%, 88.5 vs. 97.4%, and 78.2 vs. 94.4%, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Prognostic impact of frailty and fractures in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Comparison of cumulative survival rates between the (A) frailty and non-frailty groups, and (B) fracture and non-fracture groups in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Comparison of cumulative survival rates between the (C) frailty and non-frailty groups, and (D) fracture and non-fracture groups in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 96.9 vs. 96.9%, 39.2 vs. 86.2%, and 18.7 vs. 75.0% in the frailty and non-frailty groups, respectively (Fig. 4C). In the fracture and non-fracture groups, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 96.4 vs. 97.2%, 43.0 vs. 76.3%, and 27.3 vs. 60.3%, respectively (Fig. 4D). Similar to patients with compensated cirrhosis, the frailty or fracture group had significantly lower cumulative survival rates than the non-frailty or non-fracture group in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (p < 0.001 and p = 0.009, respectively).

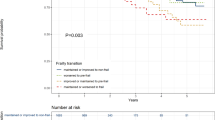

Prognostic impact of coexistence of frailty and prevalent fracture

We classified the patients into four groups based on the presence or absence of frailty and/or prevalent fractures and compared their prognoses: (i) patients with neither frailty nor prevalent fractures (n = 87), (ii) patients with prevalent fractures alone (n = 32), (iii) patients with frailty alone (n = 28), and (iv) patients with both conditions (n = 42). There were statistically significant differences in age, gender, etiology, and osteoporosis among the four groups (Supplementary Table S2). Patients with neither frailty nor prevalent fractures had the highest cumulative survival rates, whereas those with both conditions had the lowest cumulative survival rates among the four groups (log-rank: p < 0.001; Fig. 5).

Prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis

Univariate analysis revealed the significant association of decompensated cirrhosis, CP score, MELD score, total bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time (PT), Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2BPGi), osteoporosis, frailty, prevalent fractures, and HCC with mortality in the overall cohort (Supplementary Table S3); age, osteoporosis, frailty, fractures, and HCC in patients with compensated cirrhosis (Supplementary Table S4); and albumin, osteoporosis, frailty, and fractures in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Supplementary Table S5). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis identified the following variables as significant and independent prognostic factors in all patients: decompensated cirrhosis (hazard ratio [HR], 6.079; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.134–11.795; p < 0.001), total bilirubin (HR, 1.251; 95%CI 1.043–1.502; p = 0.016), frailty (HR, 3.564; 95%CI 1.918–6.625; p < 0.001), prevalent fractures (HR, 2.470; 95%CI 1.365–4.472; p = 0.003), and HCC (HR, 3.274; 95%CI 1.676–6.394; p < 0.001;Table 3). The significant and independent prognostic factors were prevalent fractures (HR, 4.985; 95%CI 1.555–15.983; p = 0.007) and HCC (HR, 6.503; 95%CI 2.236–18.913; p < 0.001) in patients with compensated cirrhosis (Supplementary Table S6) and frailty (HR, 4.902; 95%CI 2.298–10.459; p < 0.001) in those with decompensated cirrhosis (Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

Frailty increases the risk of falls and subsequent fractures, while fractures increase the risk of impaired physical performance and frailty, implying that these two comorbidities are intricately intertwined and negatively impact each other25,26,27,28,30,31,32. More importantly, both frailty and fractures are associated with mortality in older adults25,26,27,28,33,34,35. Although frailty has been reported to increase the mortality risk in patients with cirrhosis10,11,12,13, no studies have addressed the impact of fractures on the patient prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on the relationship between frailty, prevalent fractures, and prognosis in patients with cirrhosis. We also investigated whether the coexistence of frailty and prevalent fractures worsens the patient prognosis, revealing that patients with frailty had higher rates of prevalent fractures than those without and vice versa. Moreover, multivariate analysis revealed frailty and prevalent fractures as significant and independent factors related to mortality in all patients. The survival rates in the frailty or fracture group were lower than those in the non-frailty or non-fracture group in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. In the subgroup analysis, both patients with symptomatic fractures and those with asymptomatic fractures had lower survival rates than those without fractures. Notably, patients with both frailty and prevalent fractures showed lower survival rates than those without both and with either condition.

The CP classification, consisting of serum albumin, total bilirubin, PT, ascites degree, and encephalopathy grade, has been generally used to evaluate liver functional reserve36. Patients with CP class B or C have a worse prognosis than those with CP class A37. However, the CP scoring system includes subjective parameters (i.e., ascites and encephalopathy); therefore, the assessment of liver functional reserve varies among physicians, which may reduce the accuracy of prognosis prediction38. Additionally, this scoring system can hardly discriminate the prognosis of patients with compensated cirrhosis39. In this study, frailty and prevalent fractures as well as decompensated cirrhosis (nearly corresponding to CP class B/C) and total bilirubin were identified as significant independent factors in all patients. However, the CP score and its related factors were not significant independent factors when analyzed separately for patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Meanwhile, prevalent fractures in patients with compensated cirrhosis and frailty in patients with decompensated cirrhosis were identified as significant independent factors. Therefore, routine assessments of these comorbidities in clinical settings are useful and indispensable for determining the prognosis of patients with cirrhosis.

A study assessing frailty by gait speed reported that frailty increased the risk of cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization (e.g., ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, and infections) in patients with advanced cirrhosis8. A previous study classified patients with compensated cirrhosis as robust, pre-frail, or frail according to the Liver Frailty Index [LFI]) and assessed the differences between the groups. The pre-frail and frail groups showed significantly higher cumulative rates of decompensation and unplanned hospitalizations and lower decompensation-free survival rates compared with the robust group9. Another study revealed an association between frailty (assessed using the LFI) and an increased risk of progression to the next stage of cirrhosis (assessed using the D’Amico classification) or death in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis11. Our study demonstrated that the frailty group had lower survival rates than the non-frailty group in both patients with compensated cirrhosis and those with decompensation. Collectively, these findings indicate that regardless of the degree of liver functional reserve, an association exists between frailty and the development of cirrhosis-related events, disease progression, and poor prognosis in patients with cirrhosis.

Meta-analyses of community-dwelling older adults reported that frailty was a predictor of recurrent falls and fractures40,41. In general, factors associated with frailty development, such as malnutrition, physical inactivity, sarcopenia, reduced IGF-1 and vitamin D levels, and increased oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines (such as interleukin-6) with aging and cirrhosis, are also risk factors for osteoporosis15,42,43,44,45,46, and frailty is associated with decreased BMD in the elderly and patients with CLD1,47. Additionally, conditions with increased oxidative stress cause AGEs accumulation in bone and bone quality deterioration, thereby reducing bone strength19. Thus, patients with frailty at high risk of falls, reduced BMD, and bone quality deterioration are more susceptible to fractures. In older adults without CLD, fractures increase the risk of mortality. A 5-year follow-up study reported that all major fractures were associated with mortality in both men and women, and even minor fractures were associated with poor prognosis in men34. The mortality rates in controls were 37.2 in women and 49.7 in men per thousand person-years, while those in patients with fractures were 73.0 in women and 166.5 in men per thousand person-years. Additionally, a 22-year follow-up study reported that patients with vertebral fractures had higher mortality rates in both genders than control participants35. In support of these results, bisphosphonate treatment reduced all-cause mortality and was a significant independent factor associated with mortality (HR, 0.59) in patients with vertebral fractures48. However, the prognostic value of prevalent fractures has not yet been clarified in patients with cirrhosis. Our study demonstrated that the 5-year cumulative survival rates in the fracture group were considerably lower than those in the non-fracture group: 58.6 vs. 84.0% in all patients, 78.2 vs. 94.4% in patients with compensated cirrhosis, and 27.3 vs. 60.3% in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Given that patients with cirrhosis have a worse prognosis than the general population, complications of fractures in these patients further worsen their prognosis and require more careful follow-up than in the general population. As previously reported49, vertebral fractures were the most common of all fractures in this study. Notably, more than half (29/56; 51.8%) of patients with vertebral fractures were unaware of the fracture and were newly diagnosed using spine radiographs. Similar to patients with symptomatic fractures, survival rates were significantly lower in those with asymptomatic fractures than in those without fractures. It has been estimated that only one-third of all vertebral fractures are clinically diagnosed in the general population50. A recent meta-analysis of 28 studies revealed that the pooled prevalence of Vertebral Fracture Assessment-based vertebral fractures was 28% in asymptomatic postmenopausal women51. Importantly, all vertebral fractures, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, are associated with increased mortality and morbidity50. Thus, vertebral fracture underdiagnosis is a major health concern, and routine examinations with spine radiographs are essential, especially in patients at fracture risk.

In this study, patients with both frailty and prevalent fractures had the lowest survival rates among the four stratified groups. Fractures cause pain, impaired physical performance, poor balance, and low muscle strength, leading to the development and progression of frailty30,31,32. Our findings revealed that the fracture group had higher frailty prevalence and frailty scores than the non-fracture group. A study conducted on older adults reported significantly higher frailty prevalence in patients with vertebral fractures than in control participants, and the presence of ≥ 3 fractures was identified as an independent factor associated with frailty32. Another study demonstrated that the rate of prevalent fractures showed a stepwise increase with increasing levels of the frailty index comprising 33 items25. It was also reported that the risk of disease progression or death increased by 5% and 6% in patients with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, respectively, for every 0.1 unit increase in LFI11. Collectively, these findings suggest that fractures exacerbate frailty, predisposing patients to falls and further fractures and that the coexistence of both conditions (which adversely affect each other) may contribute to disease progression and increased mortality. Therefore, routine assessments and early interventions for these comorbidities are crucial to improving the quality of life and prognosis of patients. Despite their clinical importance, comprehensive assessments of frailty and bone diseases remain inadequate in real-world clinical settings where time/effort and space are limited. To address these challenges, we propose a multidisciplinary approach to managing these critical comorbidities.

This study had some limitations. First, we did not investigate the number of falls, which might have affected the development of fractures. Second, the details on fracture onset, particularly asymptomatic vertebral fractures, were unknown, and cumulative survival rates were evaluated based on the presence or absence of prevalent fractures upon study enrolment. Finally, this was a two-center study and the sample size was insufficient to evaluate the impact of frailty and prevalent fractures in the subgroup analysis. Therefore, prospective, large-scale, and multi-center studies are necessary to confirm the impact of these comorbidities on the patient prognosis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found frailty and prevalent fractures as significant and independent factors associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, the coexistence of frailty and prevalent fractures worsened the patient prognosis. From a prognostic perspective, routine assessments and early interventions for these comorbidities are crucial.

Methods

Participants

A total of 189 consecutive patients diagnosed with cirrhosis between 2017 and 2020 at the Jikei University School of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) and Fuji City General Hospital (Shizuoka, Japan) were enrolled in this retrospective study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥ 20 years and (2) presence of cirrhosis diagnosed based on laboratory and imaging tests (e.g., ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging)52. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) presence of malignancy other than HCC at study enrolment; (2) HCC not meeting the Milan criteria53; and (3) acute liver failure.

Serum total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, M2BPGi (liver fibrosis marker), and PT were measured using standard laboratory methods. Liver functional reserve was assessed based on the MELD score and CP classification36,54. Decompensated cirrhosis was defined as the presence of complications: ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and/or jaundice55. The study endpoint was liver disease-related deaths, and non-liver-related deaths were considered censored. Patients who underwent liver transplantation during the observation period were considered liver disease-related deaths and censored cases. This study was designed and conducted in accordance with the 2013 amendment of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committees of the Jikei University School of Medicine (approval number: 34–021) and Fuji City General Hospital (approval number: 279). All participants provided written informed consent.

Frailty assessment

Frailty was diagnosed according to the Fried phenotype criteria: weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and low physical activity56. Each component was defined as follows: (1) weight loss: weight loss ≥ 2 kg in the past 6 months; (2) weakness: reduced handgrip strength < 26 kg for men and < 18 kg for women; (3) exhaustion: a positive response to the question, “In the last two weeks, have you felt tired without a reason?”; (4) slowness: gait speed < 1.0 m/s; and (5) low physical activity: a negative response to the question: “Do you regularly exercise or play sports for your health?”1,57. Handgrip strength was measured using a digital dynamometer (T.K.K5401 GRIP-D, Takei Scientific Instruments, Niigata, Japan). Gait speed was assessed over a distance of 6 m. Each component was scored 1 point if applicable, and the frailty score was calculated by summation, with a score of ≥ 3 points being defined as frailty1,57.

Osteoporosis and fracture assessment

BMD was assessed at the lumbar spine (L2–L4), femoral neck, and total hip using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (PRODIGY; GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Osteoporosis was diagnosed based on a T-score ≤ − 2.5 as per the World Health Organization criteria58. Prevalent fractures were defined as a history of fractures of the vertebrae, distal radius, proximal humerus or femur, lower extremity, ribs, or pelvis that occurred after the age of 40 years18,59. Medical records and questionnaires were used to survey the history of these fractures. All participants underwent lateral thoracolumbar spine radiographs to assess prevalent vertebral fractures according to Genantʼs semi-quantitative method 60

Statistical analysis

Intergroup differences were determined using the chi-square test for categorical variables (presented as numbers and percentages) and the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables (presented as medians and interquartile ranges). Cumulative survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between the groups using the log-rank test, followed by the Bonferroni multiple-comparison method. Univariate analysis was initially used to identify mortality-related factors with p-values < 0.10. Subsequently, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed using forward stepwise selection to identify factors that were significantly and independently associated with mortality. SPSS version 27 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was used for all statistical analyses. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data collected and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Saeki, C. et al. Relationship between osteosarcopenia and frailty in patients with chronic liver disease. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2381 (2020).

Laube, R. et al. Frailty in advanced liver disease. Liver Int. 38, 2117–2128 (2018).

Tandon, P., Montano-Loza, A. J., Lai, J. C., Dasarathy, S. & Merli, M. Sarcopenia and frailty in decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 75(Suppl 1), S147–S162 (2021).

Lai, J. C. et al. Malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis: 2021 practice guidance by the american association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 74(3), 1611–1644 (2021).

Nishikawa, H., Fukunishi, S., Asai, A., Nishiguchi, S. & Higuchi, K. Sarcopenia and frailty in liver cirrhosis. Life (Basel) 11, 399 (2021).

Padhi, B. K. et al. Prevalence of frailty and its impact on mortality and hospitalization in patients with cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 14, 101373 (2024).

Nishikawa, H. et al. Health-related quality of life and frailty in chronic liver diseases. Life (Basel). 10, 76 (2020).

Dunn, M. A. et al. Frailty as tested by gait speed is an independent risk factor for cirrhosis complications that require hospitalization. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 1768–1775 (2016).

Siramolpiwat, S. et al. Frailty as tested by the Liver Frailty Index is associated with decompensation and unplanned hospitalization in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 56, 1210–1219 (2021).

Tandon, P. et al. A rapid bedside screen to predict unplanned hospitalization and death in outpatients with cirrhosis: A prospective evaluation of the clinical frailty scale. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 1759–1767 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Frailty is associated with increased risk of cirrhosis disease progression and death. Hepatology 75, 600–609 (2022).

Lai, J. C. et al. Frailty predicts waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Am. J. Transplant 14, 1870–1879 (2014).

Lai, J. C. et al. Frailty associated with waitlist mortality independent of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in a multicenter study. Gastroenterology 156, 1675–1682 (2019).

Saeki, C. et al. Comparative assessment of sarcopenia using the JSH, AWGS, and EWGSOP2 criteria and the relationship between sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and osteosarcopenia in patients with liver cirrhosis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 615 (2019).

Saeki, C., Saito, M., Tsubota, A. Association of chronic liver disease with bone diseases and muscle weakness. J. Bone Miner Metab. 2024. Online ahead of print.

Lupoli, R. et al. The risk of osteoporosis in patients with liver cirrhosis: A meta-analysis of literature studies. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 84, 30–38 (2016).

Saeki, C. et al. Osteosarcopenia predicts poor survival in patients with cirrhosis: A74 retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 196 (2023).

Saeki, C. et al. Plasma pentosidine levels are associated with prevalent fractures in patients with chronic liver disease. PLoS One 16, e0249728 (2021).

Saito, M. & Marumo, K. Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: A possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos. Int. 21, 195–214 (2010).

Liang, J. et al. The association between liver cirrhosis and fracture risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 89, 408–413 (2018).

Wester, A., Ndegwa, N. & Hagström, H. Risk of fractures and subsequent mortality in alcohol-related cirrhosis: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 1271–1280 (2023).

Chen, T. L. et al. Risk and adverse outcomes of fractures in patients with liver cirrhosis: Two nationwide retrospective cohort studies. BMJ Open 7, e017342 (2017).

Chang, C. H. et al. Increased incidence, morbidity, and mortality in cirrhotic patients with hip fractures: A nationwide population-based study. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong) 28, 2309499020918032 (2020).

Schönau, J., Wester, A., Schattenberg, J. M. & Hagström, H. Authors reply: Risk of fractures and postfracture mortality in 3980 people with primary biliary cholangitis. J. Intern. Med. 294, 537–538 (2023).

Fang, X. et al. Frailty in relation to the risk of falls, fractures, and mortality in older Chinese adults: Results from the Beijing longitudinal study of aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 16, 903–907 (2012).

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Stone KL, Cauley JA, Tracy JK, Hochberg MC, Rodondi N, Cawthon PM; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 744–751 (2007).

Middleton, R. et al. Mortality, falls, and fracture risk are positively associated with frailty: A SIDIAP cohort study of 890,000 patients. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 77, 148–154 (2022).

Dent, E., Dalla Via, J., Bozanich, T., Hoogendijk, E. O., Gebre, A. K., Smith, C., et al. Frailty increases the long-term risk for fall and fracture-related hospitalizations and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older women. J. Bone Miner Res. 2024. Online ahead of print.

Lindsay, R. et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA 285, 320–323 (2001).

Lyles, K. W. et al. Association of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures with impaired functional status. Am. J. Med. 94, 595–601 (1993).

Szulc, P. Impact of bone fracture on muscle strength and physical performance-narrative review. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 18, 633–645 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Prevalence of frailty in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture and its association with numbers of fractures. Yonsei. Med. J. 59, 317–324 (2018).

Brown, J. P. et al. Mortality in older adults following a fragility fracture: Real-world retrospective matched-cohort study in Ontario. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 105 (2021).

Center, J. R., Nguyen, T. V., Schneider, D., Sambrook, P. N. & Eisman, J. A. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353, 878–882 (1999).

Hasserius, R., Karlsson, M. K., Jónsson, B., Redlund-Johnell, I. & Johnell, O. Long-term morbidity and mortality after a clinically diagnosed vertebral fracture in the elderly–a 12- and 22-year follow-up of 257 patients. Calcif. Tissue Int. 76, 235–242 (2005).

Pugh, R. N., Murray-Lyon, I. M., Dawson, J. L., Pietroni, M. C. & Williams, R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br. J. Surg. 60, 646–649 (1973).

D’Amico, G., Garcia-Tsao, G. & Pagliaro, L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. J. Hepatol. 44, 217–231 (2006).

Kok, B. & Abraldes, J. G. Child-pugh classification: Time to abandon?. Semin. Liver Dis. 39, 96–103 (2019).

Tapper, E. B. et al. Body composition predicts mortality and decompensation in compensated cirrhosis patients: A prospective cohort study. JHEP Rep. 2, 100061 (2019).

Cheng, M. H. & Chang, S. F. Frailty as a risk factor for falls among community dwelling people: Evidence from a meta-analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 49, 529–536 (2017).

Kojima, G. Frailty as a predictor of fractures among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone 90, 116–122 (2016).

Rolland, Y. et al. Frailty, osteoporosis and hip fracture: causes, consequences and therapeutic perspectives. J. Nutr. Health Aging 12(5), 335–346 (2008).

Qu, T., Yang, H., Walston, J. D., Fedarko, N. S. & Leng, S. X. Upregulated monocytic expression of CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL-10) and its relationship with serum interleukin-6 levels in the syndrome of frailty. Cytokine 46, 319–324 (2009).

Pratim Das, P. & Medhi, S. Role of inflammasomes and cytokines in immune dysfunction of liver cirrhosis. Cytokine 170, 156347 (2023).

Álvarez-Satta, M. et al. Relevance of oxidative stress and inflammation in frailty based on human studies and mouse models. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 9982–9999 (2020).

Zhivodernikov, I. V., Kirichenko, T. V., Markina, Y. V., Postnov, A. Y. & Markin, A. M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of osteoporosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15772 (2023).

Sternberg, S. A. et al. Frailty and osteoporosis in older women–a prospective study. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 763–768 (2014).

Iida, H. et al. Bisphosphonate treatment is associated with decreased mortality in patients with after osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 1147–1154 (2022).

Santos, L. A. & Romeiro, F. G. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis-related osteoporosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 1423462 (2016).

Lindsay, R. et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA 285(3), 320–323 (2001).

Yang, J., Mao, Y. & Nieves, J. W. Identification of prevalent vertebral fractures using vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) in asymptomatic postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone 136, 115358 (2020).

Sharma, S., Khalili, K. & Nguyen, G. C. Non-invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 16820–16830 (2014).

Mazzaferro, V. et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 693–699 (1996).

Malinchoc, M. et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 31, 864–871 (2000).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 69: 406–60, (2018).

Fried, L. P. et al. Cardiovascular health study collaborative research group Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 5, 146–156 (2001).

Aida, K. et al. Usefulness of the simplified frailty scale in predicting risk of readmission or mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. Int. Heart J. 61, 571–578 (2020).

WHO. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. WHO Study Group. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 1994;843: 1–129.

Shiraki, M., Kashiwabara, S., Imai, T., Tanaka, S. & Saito, M. The association of urinary pentosidine levels with the prevalence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 37, 1067–1074 (2019).

Genant, H. K., Wu, C. Y., van Kuijk, C. & Nevitt, M. C. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J. Bone Miner. Res. 8, 1137–1148 (1993).

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S. and M.Saito. participated in the study conception and design. T.N., C.S., T.O., H.K., T.K., K.U., M.N., and Y.T. collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. T.N, C.S., and A.T. drafted the manuscript. M.Saito., M.Saruta., and A.T. interpreted the data and extensively revised the manuscript. A.T. substantively revised and completed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niwa, T., Saeki, C., Saito, M. et al. Impact of frailty and prevalent fractures on the long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 186 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83984-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83984-2

This article is cited by

-

Impact of age on frailty in liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2025)