Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to assess the effects of movement representation techniques (MRT) on pain, range of motion, functional outcomes, and pain-related fear in patients with non-specific shoulder pain (NSSP). A literature search conducted in PubMed, PEDro, EBSCO, Scopus, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, and gray literature on April 31, 2023. We selected seven randomized controlled trials based on the PICOS framework. Incomplete data or non-NSSP excluded. Study quality was assessed using the PEDro scale (mean score = 6.43), and certainty of evidence was evaluated with the GRADE approach. MRT demonstrated a large effect size for pain reduction (high heterogeneity, I2 = 85.2%, Hedges’g = 1.324, 95% CI = 0.388–2.260, P = 0.006), functional improvement (moderate heterogeneity, I2 = 70.82%, Hedges’g = 1.263, 95% CI = 0.622–1.904, P < 0.001), and reduction of pain-related fear (moderate heterogeneity, I2 = 70.86%, Hedges’g = 0.968, 95% CI = 0.221–1.716, P < 0.001). MRT also showed significant benefits for range of motion, particularly in flexion (low heterogeneity, I2 = 26.38%, Hedges’g = 0.683), abduction (low heterogeneity, I2 = 33.27%, Hedges’g = 0.756), and external rotation (low heterogeneity, I2 = 48.33%, Hedges’g = 0.542) (P < 0.001 for all), while no significant effect was found for internal rotation (P > 0.05). No publication bias was detected. While limited evidence and methodological concerns necessitate further research, MRT appears to positively impact pain, range of motion, functional outcomes, and pain-related fear in NSSP patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shoulder pain, the third most common musculoskeletal complaint after low back and neck pain, accounts for 16% of patients presenting to primary health care with musculoskeletal pain1. The incidence of shoulder pain has been reported as 6.6–25 per thousand, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 67% in different populations2,3. Shoulder pain is characterized by a strong episodic nature with high recurrence rates. Only half of patients improve within the first six months, and 40% still report problems after one year4. Therefore, shoulder pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions associated with chronic pain4. The diagnostic process for patients presenting with shoulder pain is challenging due to the lack of consensus regarding diagnostic criteria and the fact that many orthopedic tests lack specificity for any pathological condition. Two or more problems often coexist, leading clinicians to often fail to accurately diagnose the more relevant pathology of the shoulder5,6. For these reasons, clinical research tends to use the term non-specific shoulder pain (NSSP) rather than a specific diagnosis. Non-specific shoulder pain is defined as shoulder pain that occurs after excluding shoulder pain due to conditions such as tumor, infection, trauma, systemic inflammatory disorders and referred pain5,7.

Modern pain neuroscience provides evidence that a significant part of the pain experience is related to central sensitization, characterized by heightened responsiveness of the central nervous system and its contribution to chronic pain. Indeed, some studies on patients with NSSP have demonstrated a reduction in cortical excitability of the primary motor cortex8,9 and a reorganization of the somatosensory cortex (high levels of neural activation in the secondary somatosensory cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, and amygdala) during periods of pain8,9,10. In addition, a relationship between pain severity and chronicity and decreased motor cortex excitability has been observed in these patients9. These findings suggest that while sensory and motor representations of the body can be modulated and lead to perceptual changes10,11,12, treatments that reduce pain also normalize organization in the primary somatosensory cortex13,14.

The application of this knowledge to rehabilitation practice is a hot topic. Especially in chronic pain with suspected central sensitization, somotosensory and motor cortex modifiable therapies are exciting for all musculoskeletal physiotherapists around the world. The potential for preventive and therapeutic changes in the central nervous system implies that these treatments can be applied both proactively, to prevent pain from becoming chronic, and reactively, after pain has already become chronic. A group of rehabilitation methods defined as movement representation techniques (MRT) are also used in musculoskeletal pain15,16,17,18.

-

Action observation involves the observation of normal, painless movements to evoke an internal motor simulation of motor movement15.

-

Mirror therapy is based on observing the movements of the patient’s intact limb in a mirror, thereby creating a visual illusion that excludes the affected limb from view16.

-

Visual mirror feedback therapy provides patients with real-time visual input of their movements as seen in the mirror during performance16.

-

Motor imagery trains cognitive skills by mentally simulating movements without physical execution, forming a mental representation of the intended movement16,17.

-

Graded motor imagery combines right-left discrimination, motor imagery, and mirror therapy to enhance rehabilitation outcomes through a structured approach18.

These techniques are reported to reduce pain by manipulating sensory and motor integration within the central nervous system. It has been demonstrated that MRT can cause a modulation in cortical representation and excitability by affecting areas such as the primary motor and somatosensory cortex or the dorsal premotor cortex. This has also been associated with a reduction in pain perception17,19,20,21 and these results has been related to changes in neural plasticity22.

MRT has been widely used to induce neuroplastic changes at the central level in a variety of clinical painful conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome, phantom limb pain, low back pain and pain following hemiplegia16,18,23,24,25. In addition, MRT has been shown to modulate pain in these diseases in systematic reviews and meta-analyses18,23,25,26,27. There is no comprehensive review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of MRT in patients with non-specific shoulder pain (NSSP). Accordingly, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to determine whether MRT plays a positive role in the rehabilitation of patients with NSSP. Therefore, the main objective of this review is to systematically examine and meta-analyze the effects of motor imagery, action observation, mirror therapy, visual mirror feedback therapy and graded motor imagery techniques on pain, range of motion, functional outcomes and pain-related anxiety in patients with NSSP.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This meta-analysis was conducted in strict accordance with the ‘preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses’ (the ‘PRISMA’ statement)28. This systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under reference number CRD42024541908.

Search strategy

Two independent researchers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.) conducted a systematic literature search in six databases: PubMed, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), EBSCO, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and ScienceDirect on April 31, 2023. The language was restricted to English and Turkish. The authors constructed, reviewed and calibrated the search strategy in the PubMed/Medline database using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies guidelines29. The search strategy, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords, was developed for participants and interventions in consultation with a librarian and content experts. Additionally, a comprehensive search strategy was employed to capture relevant evidence across a broader spectrum. First, the OpenGrey database was used to identify unpublished studies in the grey literature. Second, the reference lists of key articles were meticulously hand-searched for additional potential studies. Finally, our research was restricted to peer-reviewed articles and full-text theses published in English or Turkish, focusing on adult populations. To ensure accuracy and minimize bias, two independent reviewers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.) conducted the research. The search strategies were adjusted according to the individual database requirements. (Apendix 1). Rayyan30, (free web-based tool; https://www.rayyan.ai/; Qatar Computing Research Institute, Qatar) was used to identify and remove duplicate studies and review articles.

Eligibility criteria

The selection of studies was based on the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, and Study design) framework31, in consultation with a librarian and content experts. This framework served as a guide in determining the eligibility criteria and specific, focused objectives for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The PICOS framework was defined as follows:

-

Participants (P): Adults (18 years and older) with non-specific shoulder pain. This included patients with atraumatic unilateral shoulder pain and/or disability symptoms associated with subacromial pain syndrome, impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tendinitis, rotator cuff tear, bursitis, periarthritis, osteoarthritis, adhesive capsulitis, and frozen shoulder.

-

Interventions (I): Motor imagery, action observation, mirror therapy, visual mirror feedback therapy and graded motor imagery, administered alone or in combination.

-

Comparisons (C): A group receiving no intervention, placebo, or another conservative intervention.

-

Outcomes (O): Studies that evaluated pain intensity, range of motion, strength, shoulder function, and fear of pain, alone or in combination.

-

Study design (S): Randomized controlled trials, randomized parallel-designed controlled trials, and prospective controlled clinical trials. Studies were limited to the English and Turkish language.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are as follows:

-

Studies investigating conditions such as tumors, infections, fractures, systemic inflammatory disorders, referred pain from other sources, neurological symptoms, neck pain, or radiculopathy.

-

Studies without complete and accessible full texts. Authors of studies lacking full text were contacted, but those who did not respond were excluded.

Selection process

Prior to the screening, all authors independently reviewed a random sample of 120 titles/abstracts (10% of the total records) to assess the applicability of the inclusion/exclusion criteria for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The two reviewers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.) who conducted the screening achieved acceptable inter-rater reliability [%98.1-%99, κ = 0.795–0.852] with the senior author (N.A.)32.

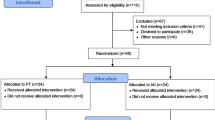

The selection of studies was independently conducted by two reviewers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.), both physiotherapists pursuing their doctorates in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. The reviewers assessed all titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, they reviewed the full texts of studies that met the eligibility criteria. The inclusion of each study was determined by consensus after an independent review by all authors. In instances where consensus could not be reached, the final decision was made by the senior author (N.A.). Contact with the author of one study was necessary due to missing information or limited access to the full text (n = 1), and the author provided the requested full text and missing data33. The flowchart illustrates the screening procedure and criteria for exclusion (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

Following the selection of studies, two researchers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.) independently gathered the data using a Cochrane Library Data collection form. The authors worked independently to extract study data. Consensus was then reached on data extraction through discussion with the senior author when there was a conflict. Data from included studies included author name, year, population characteristics, groups, assessment time points, outcome measures and summary of results (Table 1). Data such as medians, interquartile ranges and mean ± 95% confidence interval were converted to mean ± SD following the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.2. If a study had data available for more than one time point (e.g. at three, four, five and six weeks) for any of the outcome measures, data from the latest time point were taken and standardized mean difference and variance calculations were performed for continuous data for these values and baseline values34,35.

Methodological quality, risk of bias and certainty assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included reports using appropriate assessment tools. The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale, a critical appraisal tool designed for experimental physiotherapy studies. The PEDro scale, developed by Verhagen et al.36, consists of 11 items out of a total score of 10, as the first question is not included in the calculation. A score of 9 or 10 was considered excellent quality, 6 to 8 was considered good, and 4 or 5 was considered fair quality. Studies with a score below 4 points are considered to be of poor quality37. PEDro scores for the included trials were retrieved from the PEDro website (https://www.pedro.org.au/)37. In cases where a trial’s score was unavailable on the PEDro website, two independent reviewers (A.Ö.A. and S.Ö.) evaluated methodological quality based on the 10 items of the PEDro scale. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion with the senior author (N.A.), who was blinded to prior review scores. No specific PEDro score cut-off value was used as an exclusion criterion in this review.

Reporting bias was assessed using a combination of visual and statistical methods. Funnel plots were generated to visually examine the symmetry of study effect sizes, and asymmetry was further analyzed using Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test and Egger’s regression test. In cases where asymmetry was detected, the Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method was employed to estimate the number of missing studies and their potential impact on the pooled effect size38,39. To evaluate the certainty of the evidence, the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) framework was applied as suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration40. This included assessing the risk of bias (using the PEDro scale to evaluate methodological quality), inconsistency (via the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity), indirectness, imprecision (based on sample sizes and confidence intervals), and publication bias (using the aforementioned funnel plot analyses). Two reviewers, A.Ö.A. and S.Ö., evaluated the certainty of evidence, and a third reviewer, N.A., was involved to resolve any disagreements. Final quality of evidence was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low37.

Data synthesis and analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software Version 3 (CMA V3, Biostat Inc.). For the analysis of continuous data, standardized mean difference and variance calculations were made from the values given in the study34,35 and inputted into the CMA software. When the homogeneity test statistics were insignificant, the fixed effects model was used to estimate the overall effect, whereas when heterogeneity was p ≤ 0.05, the random effects model including the restricted maximum likelihood estimation method was used. The random effects model was used for pain, function and fear of pain data and the fixed effects model was used for range of motion data only. The I2 statistic was used to measure heterogeneity between included studies. An I2 value of 25% indicates a low degree of heterogeneity, 50% a moderate degree and 75% a high degree41. Since the sample sizes of the studies were mostly below twenty participants, Hedges’s g value was combined for the estimates and an effect size of 0.2 was considered small, 0.5 medium and 0.8 large38. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot, Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test and Egger’s regression test for included studies. In case of asymmetry, the mean effect size was recalculated using the asymmetry correction and fill method. By performing the effect size calculation according to Duval and Tweedie’s calculation; it was estimated how many more studies should be done and how the average effect size that would occur with these publications would be compared with the effect size that occurred according to the meta-analysis result39.

Results

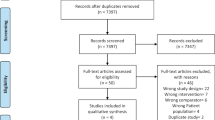

A total of 1647 studies were identified through the search strategy, including 204 from MEDLINE via PubMed, 492 from EBSCO, 347 from SCOPUS, 182 from the Cochrane Library, 147 from PEDro, and 275 from grey literature. During the screening process, 351 duplicate records from the databases and 9 duplicates from the grey literature were identified and excluded, resulting in 1287 unique studies being assessed for eligibility (Table 1). During the screening phase, 17 records were excluded due to being in a foreign language, 328 due to incorrect publication type, 612 due to inappropriate population, 48 due to study design, and 4 due to irrelevant interventions. Consequently, 12 reports were sought for full-text retrieval, and all were successfully retrieved. Following a detailed eligibility assessment, 6 reports were excluded: 1 due to inappropriate population and 5 due to irrelevant interventions. Additionally, 8 reports from other sources were assessed, with 7 excluded due to study design (4) or inappropriate population (3). Ultimately, 7 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis. This process is summarized in Fig. 1.

The PEDro scores of the included studies ranged from 5 to 8 (out of a maximum score of 10), with a mean score of 6.43 (Table 2). Six of the seven studies33,42,43,44,45,46 were rated as good quality and one study47 as moderate quality (Table 2).

Three of the seven studies included mirror therapy33,44,45, two included graded motor imagery42,46 the others included action observation therapy47, motor imagery43 and visual mirror feedback33. Since the study of Hekim et al. included both mirror therapy and visual mirror feedback therapy in the intervention group, the data of this study were included in the meta-analysis as two different data groups. Two of the studies investigated the effect of MRT in shoulder impingement syndrome43,45, while the others included patients with adhesive capsulitis44,47, also called frozen shoulder33,42,46. The characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 3. A total of 244 patients were included from the studies analyzed in this review.

Figure 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis of the effects of MRT on pain, function and fear of pain in patients with NSSP. Pain intensity in all studies included in the meta-analysis was measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The mean difference in VAS scores pre- and post-intervention mean was 3.72 (95% CI: 2.70–4.44) in the control group, compared to 5.26 (95% CI: 4.56–5.94) in the treatment group. In the meta-analysis calculations on pain intensity, based on the random effects model, a significant mean difference in favor of the MRT groups was found with an effect size of 1.324 (95% CI = 0.388–2.260, P = 0.006, Fig. 2A) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 85.2%). The Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test (p = 0.138) and Egger’s regression intercept (p = 0.130) scores were not statistically significant in addition to the funnel plot analysis (Fig. 3A), indicating that no publication bias was found. According to Duval and Tweedie, although two additional studies were required for publication bias, the effect size decreased from 1.324 to 0.747 even if these two publications were included. Therefore, it was determined that MRT was highly effective on pain in patients with NSSP in favor of the treatment groups and no publication bias was observed in the studies.

In the meta-analysis of shoulder functionality, based on a random effects model, an effect size of 1.263 (95% CI = 0.622–1.904, P < 0.001, Fig. 2B) was found to produce a highly significant mean difference with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70.82%). In the publication bias analysis, in addition to the funnel plot analysis (Fig. 3B), the Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test (p = 0.025) and Egger’s regression intercept (p = 0.075) scores were found to be statistically significant and insignificant, respectively. In Duval and Tweedie’s analysis, it was determined that 3 more studies were required to eliminate publication bias. However, even if these three publications were included, the effect size was calculated to decrease from 1.324 to 0.879. Therefore, it was determined that MRT was highly effective on functionality in patients with NSSP in favor of the treatment groups and no publication bias was observed in the studies.

A meta-analysis of four studies on fear of pain43,46,47,48, based on a random-effects model, revealed a significant mean difference in favor of the treatment groups with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70.86%). The effect size was determined to be 0.968 (95% CI = 0.221–1.716, P < 0.001, Fig. 2C). In the analysis of publication bias, the funnel plot (Fig. 3C), Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test (p = 0.497), and Egger’s regression intercept (p = 0.734) did not show statistically significant results, indicating the absence of publication bias. Despite Duval and Tweedie’s test suggesting the need for one additional study to potentially eliminate bias, the recalculated effect size decreased from 0.968 to 0.764. Therefore, it was determined that MRT was highly effective on fear of pain in patients with NSSP in favor of the treatment groups and no publication bias was observed in the studies.

In the meta-analysis calculations for range of motion related assessments (Fig. 4), based on the fixed effects model, the effect size for flexion was 0.683 (95% CI = 0.389–0.977, P < 0.001, Fig. 4A) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 26.38%), for abduction was 0.756 (95% CI = 0.452–1.060, P < 0.001, Fig. 4B) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 33. 27%), and for external rotation was 0.542 (95% CI = 0.255–0.830, P < 0.001, Fig. 4C) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 48.33%), which showed a significant moderate mean difference in favor of the treatment groups. However, in the internal rotation analysis, the effect size was 0.279 (95% CI = -0.013- 0.572, P = 0.061, Fig. 4D) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 17.81%) indicating no difference between the two groups. In the analysis of publication bias, the funnel plot (Fig. 3D-G), Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test and Egger’s regression intercept did not show statistically significant results, indicating the absence of publication bias. (p < 0.05). Duval and Tweedie’s test indicated no need for additional studies to potentially eliminate bias for flexion. However, two additional studies are required for abduction, potentially reducing the effect size from 0.756 to 0.611. Furthermore, an additional study is needed for external rotation, which may decrease the effect size from 0.542 to 0.449. Therefore, it was determined that MRT was moderately effective in improving range of motion measurements, except for internal rotation, in favor of the treatment groups among patients with NSSP, and no publication bias was observed in the studies.

The certainty of evidence for the evaluated outcomes ranged from low to high according to the GRADE criteria (Table 4). Pain intensity demonstrated a moderate certainty level, with significant effect size but high heterogeneity (I² = 85.42%). Functionality and fear of pain outcomes showed moderate-to-high and high certainty levels, respectively, supported by strong and significant effect sizes despite moderate heterogeneity. Range of motion outcomes, including flexion, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation, generally exhibited moderate certainty, with low-to-moderate heterogeneity (I² = 17.81–48.33%). However, internal rotation showed a low certainty level due to limited precision and lack of significant effects (Table 4).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of MRT in patients with NSSP across seven randomized controlled trials involving 244 patients. The quality of the included studies was rated moderate to good. Despite the limited number of studies, the findings indicate that MRT techniques are statistically more effective than conventional physiotherapy in reducing pain intensity (moderate certainty), improving range of motion (mostly moderate certainty), enhancing functional outcomes (moderate-to-high certainty), and decreasing pain-related fear (high certainty).

This meta-analysis identified a significant difference in pain intensity with MRT in patients with NSSP, characterized by a high effect size and high heterogeneity. In contrast, two studies—Walankar & Shah (2023) (action observation therapy)47 and Hekim et al.33 (Mirror therapy)—found no significant difference in pain reduction between MRT and control groups. Across all included studies, both intervention and control groups achieved a 2 cm reduction on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is considered the minimal clinically important difference according to Portney and Watkins48, except for the control group in the study by Grudut et al., 2022 42.

This indicates that while control groups, including those receiving traditional physiotherapy, also achieved clinical significance in terms of pain reduction, MRT groups are more effective in reducing pain intensity (moderate certainty). Indeed, in an umbrella and mapping review with meta-meta-analysis study by Cuenca-Martínez et al. (2021), similar to our meta-analysis results, MRT techniques were found to reduce chronic musculoskeletal pain. However, the results emphasized by our study do not include conditions such as neuropathic pain or phantom pain and post-stroke pain49. The basic mechanism by which MRT produces hypoalgesia in patients with musculoskeletal pain17 is thought to be due to the inputs generated by the techniques reorganizing cortical processes in the primary somatosensory cortex that are disrupted by pain50,51.

It has been reported that the mirror neuron system, which provides neuroanatomical support, is extensively involved in the motor learning process through movement representation52,53. Furthermore, the effects related to the representation of movement in the brain indicate that cortico-subcortical networks involved in planning, execution, adjustment, and automatization of actual movements share similar neurophysiological activity. It has been shown that this neurophysiological activity can be influenced by specific physical, cognitive-evaluative, motivational-emotional and direct modulation variables related to the movement representation process54. MRT has also been shown to have an effect on a number of intriguing variables, such as strength17,54,55 and lead to the improvement of motor learning processes56,57. The present meta-analysis supports the aforementioned mechanisms by demonstrating that MRT produces a significant difference in functionality and range of motion measurements (except for internal rotation) with a moderate effect size in patients with NSSP. Similar to the pain analysis, the mirror therapy groups in the studies by Walankar and Shah47 and Hekim et al.33 did not show statistically significant improvement in functionality (moderate-to-high certainty) compared to the control group. In addition, all intervention and control groups in the included studies achieved minimal clinical differences for measures of functionality58.

The presence of pain-induced avoidance and fear of movement has been noted in various musculoskeletal pain conditions, not limited to shoulder pain59,60,61,62. Furthermore, a negative correlation has been identified between kinesiophobia levels and the ability to form both kinesthetic and visual motor images in patients with chronic low back pain63. Additionally, it has been observed that patients with chronic low back pain exhibit impaired motor image formation abilities compared to healthy individuals63,64. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that MRT, which enhances the capacity to form visual motor images, may positively impact fear of pain. Indeed, the current meta-analysis of four studies42,45,46,47 on fear of pain (high certainty) demonstrates that MRT was highly effective.

Limitations of the study and suggestions for future studies

Although the current meta-analysis is the first to demonstrate the effect of MRT in patients with NSSP, the study has several limitations. These include the relatively high heterogeneity among the included studies, the small number of patients, variations in the timing of measurements across studies (ranging from 3 weeks to 10 weeks), and the absence of evaluation of long-term outcomes. In this meta-analysis, no publication bias was detected, and adjustments according to Duval and Tweedie’s calculations had minimal impact on the effect size values. However, the limited number of published studies increases the likelihood of publication bias. Therefore, future randomized controlled trials addressing these limitations are warranted.

In the studies included in the meta-analysis, blinding of the physiotherapist and patients could not be ensured and this constitutes one of the main limitations of the study by creating a risk of bias. Blinding was mostly based on assessor blinding. Despite this, most of the results were based on self-reported measures, which also prevented blinding of the assessors. Although blinding of participants and therapists in an exercise trial is challenging to achieve and cannot eliminate the risk of bias, future studies should at least attempt to limit potential bias through appropriate blinding of assessors. This is because certain expectations and beliefs of patients and therapists may influence the results. Furthermore, in all studies, the control group and the intervention group consisted of different groups, and there was no crossover experimental design in the studies. Consequently, the outcomes of the included studies are likely to be affected by discrepancies in exercise intensity and blinding procedure between the groups.

In all studies included in the meta-analysis, conventional physiotherapy methods included electrotherapy, range of motion exercises, stretching techniques, while in some studies mobilization46,47 and some simple strengthening exercises45,46,47 were added to these techniques. Differences between the rehabilitation of these control groups may also affect the results of the study. In addition, due to the small number of studies, all MRT techniques were included in the meta-analysis process as if they were a single technique. This constitutes one of the main limitations of the meta-analysis. Because it is concluded that the mirror neuron system works more efficiently through action observation therapy than motor imagery and action observation therapy is less demanding in terms of cognitive load than motor imagery. There is also evidence that action observation therapy may be less sensitive to the influence of variables related to motion representation54. Similarly, it has been suggested that the neuronal mechanisms behind mirror therapy and motor imagery are different65. The brain’s natural tendency to prioritize visual feedback over others is thought to make mirror therapy a more powerful tool. However, research evidence to support this hypothesis is currently lacking66,67. It is possible that there may also be differences between the visual mirror feedback group and the mirror therapy group. In fact, some studies in healthy individuals have shown that appropriate feedback can affect motor recovery and improve motor performance in the short or long term33,68,69,70,71. Specifically, in the Hekim et al. study included in the meta-analysis, visual mirror therapy was found to be superior to mirror therapy. Because graded motor imagery is a therapy that uses right-left discrimination, motor imagery, and mirror therapy in a particular way, its mechanism has not been fully explored72. Therefore, more studies comparing MRT methods and investigating mechanisms in patients with NSSP are needed in the future.

In summary, the relatively small sample sizes and heterogeneity in study designs and intervention protocols in the studies included in this meta-analysis may have influenced the results. Future research should aim to address these limitations by conducting larger, well-powered, and rigorously designed randomized controlled trials. Additionally, future studies could employ neuroimaging techniques to elucidate the neural correlates of MRT and identify potential biomarkers for treatment response. Examining the long-term effects of MRT on pain, function, and quality of life in patients with NSSP is also crucial. Although this meta-analysis focused on short-term outcomes, it is important to evaluate whether the benefits of MRT persist over time. Lastly, future research should investigate the optimal dosage and frequency of MRT sessions to maximize therapeutic benefits. Exploring the potential combination of MRT with other interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or exercise therapy, may also yield synergistic effects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although caution is warranted when interpreting these findings due to the limited number of studies included in the current meta-analysis, it was determined that MRT techniques had a positive effect on pain, range of motion, functional outcomes, and pain-related fear in NSSP patients. Given the limitations of the current studies, there is a need for further planned studies.

Data availability

“The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request”.

References

Lucas, J., van Doorn, P., Hegedus, E., Lewis, J. & van der Windt D. A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 1073. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05973-8 (2022).

Luime, J. J. et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 33, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009740310004667 (2004).

Andrews, J. R. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic painful shoulder: review of nonsurgical interventions. Arthroscopy 21, 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2004.11.003 (2005).

Laslett, M., Steele, M., Hing, W., McNair, P. & Cadogan, A. Shoulder pain patients in primary care–part 1: clinical outcomes over 12 months following standardized diagnostic workup, corticosteroid injections, and community-based care. J. Rehabil Med. 46, 898–907. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1860 (2014).

Schellingerhout, J. M., Verhagen, A. P., Thomas, S. & Koes, B. W. Lack of uniformity in diagnostic labeling of shoulder pain: time for a different approach. Man. Ther. 13, 478–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2008.04.005 (2008).

Gemmell, H., Miller, P., Jones-Harris, A., Cook, J. & Rix, J. An alternative approach to the diagnosis and management of non-specific shoulder pain with case examples. Clin. Chiropr. 14, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clch.2011.01.007 (2011).

Ristori, D. et al. Towards an integrated clinical framework for patient with shoulder pain. Arch. Physiother. 8, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-018-0050-3 (2018).

Bachasson, D., Singh, A., Shah, S. B., Lane, J. G. & Ward, S. R. The role of the peripheral and central nervous systems in rotator cuff disease. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 24, 1322–1335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.004 (2015).

Ngomo, S., Mercier, C., Bouyer, L. J., Savoie, A. & Roy, J. S. Alterations in central motor representation increase over time in individuals with rotator cuff tendinopathy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126, 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.035 (2015).

Nijs, J., Van Houdenhove, B. & Oostendorp, R. A. Recognition of central sensitization in patients with musculoskeletal pain: application of pain neurophysiology in manual therapy practice. Man. Ther. 15, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2009.12.001 (2010).

Moseley, G. L. & Flor, H. Targeting cortical representations in the treatment of chronic pain: a review. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 26, 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968311433209 (2012).

Pelletier, R., Higgins, J. & Bourbonnais, D. Is neuroplasticity in the central nervous system the missing link to our understanding of chronic musculoskeletal disorders? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0480-y (2015).

Navratilova, E. et al. Positive emotions and brain reward circuits in chronic pain. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 1646–1652. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23968 (2016).

Flor, H. The modification of cortical reorganization and chronic pain by sensory feedback. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 27, 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1016204029162 (2002).

Buccino, G. Action observation treatment: a novel tool in neurorehabilitation. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130185. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0185 (2014).

Thieme, H., Morkisch, N., Rietz, C., Dohle, C. & Borgetto, B. The Efficacy of Movement Representation Techniques for treatment of Limb Pain–A systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Pain. 17, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.015 (2016).

Suso-Martí, L., La Touche, R., Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S. & Cuenca-Martínez, F. Effectiveness of motor imagery and action observation training on musculoskeletal pain intensity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pain. 24, 886–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1540 (2020).

Moseley, G. L. Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Pain 108, 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.006 (2004).

Ramachandran, V. S. & Altschuler, E. L. The use of visual feedback, in particular mirror visual feedback, in restoring brain function. Brain 132, 1693–1710. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp135 (2009).

Araya-Quintanilla, F. et al. The short-term effect of Graded Motor Imagery on the Affective Components of Pain in subjects with Chronic Shoulder Pain Syndrome: open-label single-arm prospective study. Pain Med. 21, 2496–2501. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz364 (2020).

Wittkopf, P. & Johnson, G. (ed I, M.) Mirror therapy: a potential intervention for pain management. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 63 1000–1005 https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.63.11.1000 (2017).

Volz, M. S. et al. Movement observation-induced modulation of pain perception and motor cortex excitability. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126, 1204–1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.09.022 (2015).

Bowering, K. J. et al. The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain. 14, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.007 (2013).

Wand, B. M. et al. Seeing it helps: movement-related back pain is reduced by visualization of the back during movement. Clin. J. Pain. 28, 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31823d480c (2012).

Boesch, E., Bellan, V., Moseley, G. L. & Stanton, T. R. The effect of bodily illusions on clinical pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 157, 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000423 (2016).

Yap, B. W. D. & Lim, E. C. W. The effects of Motor Imagery on Pain and Range of Motion in Musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review using Meta-analysis. Clin. J. Pain. 35, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/ajp.0000000000000648 (2019).

Daffada, P. J., Walsh, N., McCabe, C. S. & Palmer, S. The impact of cortical remapping interventions on pain and disability in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 101, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.07.002 (2015).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 (2009).

McGowan, J. et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 75, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 (2016).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Reviews. 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 (2016).

Methley, A. M. et al. PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0 (2014).

Holt, C. J. et al. Sticking to it: a scoping review of adherence to Exercise Therapy interventions in Children and adolescents with Musculoskeletal conditions. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 50, 503–515. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.9715 (2020).

Hekim, Ö., Çolak, T. K. & Bonab, M. A. R. The effect of mirror therapy in patients with frozen shoulder. Shoulder Elb. 15, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/17585732221089181 (2023).

Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator (2023).

Lenhard, W. & Lenhard, A. Computation of Effect Sizes. (2017).

Verhagen, A. P. et al. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51, 1235–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00131-0 (1998).

Cashin, A. G., McAuley, J. H. & Clinimetrics Physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro) scale. J. Physiother. 66, 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.005 (2020).

Lin, L. & Aloe, A. M. Evaluation of various estimators for standardized mean difference in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 40, 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8781 (2021).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x (2000).

Guyatt, G. et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 (2011).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 327, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 (2003).

Gurudut, P. & Godse, A. N. Effectiveness of graded motor imagery in subjects with frozen shoulder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Korean J. Pain. 35, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.152 (2022).

Hoyek, N., Di Rienzo, F., Collet, C., Hoyek, F. & Guillot, A. The therapeutic role of motor imagery on the functional rehabilitation of a stage II shoulder impingement syndrome. Disabil. Rehabil. 36, 1113–1119. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.833309 (2014).

Başkaya, M., Erçalık, C., Karataş Kır, Ö., Erçalık, T. & Tuncer, T. The efficacy of mirror therapy in patients with adhesive capsulitis: a randomized, prospective, controlled study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 31, 1177–1182. https://doi.org/10.3233/bmr-171050 (2018).

Akdeniz Leblebicier, M. & Yaman, F. Bulut Özkaya, D. Outcomes with additional Mirror Theraphy to Rehabilitation Protocol in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: a prospective randomized controlled study. Osmangazi Tıp Dergisi. 45, 198–208. https://doi.org/10.20515/otd.1166020 (2023).

Yasacı, Z. Comparing effectiveness of two different exercise training for treatment of frozen shoulder PhD thesis, Istanbul Üniversitesi-Cerrahpaşa, (2023).

Walankar, P. & Shah, D. Effect of Action Observation Therapy on Pain, Kinesiophobia, function, and quality of life in Adhesive Capsulitis patients. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 21, 1–6 (2023).

Portney, L. G. & Watkins, M. P. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice (Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2009).

Cuenca-Martínez, F. et al. Pain relief by movement representation strategies: an umbrella and mapping review with meta-meta-analysis of motor imagery, action observation and mirror therapy. Eur. J. Pain. 26, 284–309. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1870 (2022).

Brodie, E. E., Whyte, A. & Waller, B. Increased motor control of a phantom leg in humans results from the visual feedback of a virtual leg. Neurosci. Lett. 341, 167–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00160-5 (2003).

Maihöfner, C., Handwerker, H. O., Neundörfer, B. & Birklein, F. Patterns of cortical reorganization in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology 61, 1707–1715. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000098939.02752.8e (2003).

Rizzolatti, G., Fadiga, L., Gallese, V. & Fogassi, L. Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 3, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/0926-6410(95)00038-0 (1996).

Rizzolatti, G. & Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 169–192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230 (2004).

Cuenca-Martínez, F. et al. Effects of Motor Imagery and Action Observation on Lumbo-pelvic Motor Control, Trunk Muscles Strength and level of perceived fatigue: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 91, 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2019.1645941 (2020).

Losana-Ferrer, A., Manzanas-López, S., Cuenca-Martínez, F., Paris-Alemany, A. & La Touche, R. Effects of motor imagery and action observation on hand grip strength, electromyographic activity and intramuscular oxygenation in the hand gripping gesture: a randomized controlled trial. Hum. Mov. Sci. 58, 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2018.01.011 (2018).

Cuenca-Martínez, F., La Touche, R., León-Hernández, J. V. & Suso-Martí, L. Mental practice in isolation improves cervical joint position sense in patients with chronic neck pain: a randomized single-blind placebo trial. PeerJ 7, e7681. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7681 (2019).

Gonzalez-Rosa, J. J. et al. Action observation and motor imagery in performance of complex movements: evidence from EEG and kinematics analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 281, 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.016 (2015).

Dabija, D. I. & Jain, N. B. Minimal clinically important difference of shoulder outcome measures and diagnoses: a systematic review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001169 (2019).

Alaca, N. The relationships between pain beliefs and kinesiophobia and clinical parameters in Turkish patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 69, 823–827 (2019).

Alaca, N., Kaba, H. & Atalay, A. Associations between the severity of disability level and fear of movement and pain beliefs in patients with chronic low back pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 33, 785–791. https://doi.org/10.3233/bmr-171039 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Kinesiophobia could affect shoulder function after repair of rotator cuff tears. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 714. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05679-x (2022).

Luque-Suarez, A. et al. Kinesiophobia is Associated with Pain Intensity and Disability in Chronic Shoulder Pain: a cross-sectional study. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 43, 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2019.12.009 (2020).

La Touche, R. et al. Diminished kinesthetic and Visual Motor Imagery ability in adults with chronic low back Pain. Pm r. 11, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.05.025 (2019).

Pijnenburg, M. et al. Resting-state functional connectivity of the Sensorimotor Network in individuals with Nonspecific Low Back Pain and the Association with the sit-to-stand-to-sit Task. Brain Connect. 5, 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2014.0309 (2015).

Deconinck, F. J. et al. Reflections on mirror therapy: a systematic review of the effect of mirror visual feedback on the brain. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 29, 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968314546134 (2015).

Moseley, L. G., Gallace, A. & Spence, C. Is mirror therapy all it is cracked up to be? Current evidence and future directions. Pain 138, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.026 (2008).

Diers, M., Christmann, C., Koeppe, C., Ruf, M. & Flor, H. Mirrored, imagined and executed movements differentially activate sensorimotor cortex in amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain 149, 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.020 (2010).

Barandas, M., Gamboa, H. & Fonseca, J. M. A real time Biofeedback System using Visual user interface for Physical Rehabilitation. Procedia Manuf. 3, 823–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.337 (2015).

Zipp, G. Gentile. Practice schedule and the learning of motor skills in children and adults: teaching implications. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 2, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v7i2.87 (2010).

Khan, M. A. & Franks, I. M. The effect of practice on component submovements is dependent on the availability of visual feedback. J. Mot Behav. 32, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222890009601374 (2000).

Young, D. E. & Schmidt, R. A. Augmented Kinematic Feedback for Motor Learning. J. Mot Behav. 24, 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222895.1992.9941621 (1992).

Candiri, B., Talu, B. & Karabıcak, G. O. Graded motor imagery in orthopedic and neurological rehabilitation: a systematic review of clinical studies: graded motor imagery in rehabilitation. J. Surg. Med. 7, 347–354. https://doi.org/10.28982/josam.7669 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A. and A.Ö.A. wrote the main manuscript text and A.Ö.A. and S.Ö. prepared Figs. 1-3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alaca, N., Acar, A.Ö. & Öztürk, S. Effectiveness of movement representation techniques in non-specific shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 205 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84016-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84016-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Classification of musculoskeletal pain using machine learning

Scientific Reports (2025)