Abstract

The long-term safety and durability of anchor systems are the focus of slope maintenance management and sustainable operation. This study presents the observed temperature, humidity, and anchor bolt stress at varying depths from four-year remote real-time monitoring of the selected loess highway cut-slope. The potential correlation between slope hydrothermal environment and anchor stress is analyzed. The anchor serviceability and durability were evaluated by establishing a time-dependent mathematical model of axial forces. The results show that the slope shallow loess exhibited hydro-thermal fluctuations annually during operation, subjecting the loess to continuous dry–wet cycles. Soil elastic deformation induces anchor axial force fluctuations due to hydro-thermo effects, while damage creep leads to the annual increase in axial force peaks and valleys. The increase in axial force is more significant at the upper slope and lower slope, thereby increasing the risk of retrogressive landslides in loess slopes. The time-dependent model of anchor axial force composing negative exponential and sine functions was proposed. The cyclic amplitudes, lower limits, and periods of temperature and humidity in slope can determine the model coefficients. The development patterns of axial force are classified into stable type, slow growth type, and accelerated growth type according to the characteristics of the model coefficients. Predicted results indicate that the anchor axial forces are lower than the landslide threshold within 30 years of slope operation, ensuring long safety and serviceability. Results provide a reference for the long-term safety evaluation and formulation of maintenance plans for loess slopes reinforced by anchor systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anchor bolts are widely employed as structural components in tunnels, dams, mines, bridges, and cut slopes due to their affordability, effective support, and ability to utilize the bearing capacity of rock or soil1,2,3. However, anchor bolts gradually lose their anchorage effect after years of service, becoming susceptible to tension or debonding failure, which has led to engineering risks4,5,6. These failures can reduce the structure’s service life, shorten maintenance periods, and impose significant economic burdens and operational and managerial difficulties in engineering. Therefore, the reasonable assessment of the anchor bolt’s reliability and serviceability is essential for evaluating the long-term stability for reinforcement projects.

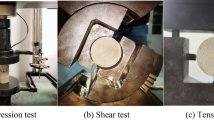

Anchorage systems can be classified into passive anchors and active anchors (also known as prestressed anchors) based on their functioning mode. Passive anchors do not exert tension and are activated when the protective structure undergoes displacement. In contrast, prestressed anchors are pre-tensioned in advance, and their anchorage length typically encompasses the total length or a portion of it7,8. The stress of anchor bolts is primarily influenced by rock deformation, anchorage depth, construction quality, and the external environment9,10. Long-term stress variations cause prestressed anchor bolts to experience stress loss, while the axial tension borne by full-length bond grouted anchors increases, resulting in the degradation of the anchoring system’s durability11,12. Previous research has been conducted to evaluate the long-term performance of rock-soil-anchoring systems under axial loads. Pull-out and shear tests have been primarily used to measure the bearing capacity of anchorage systems10,13,14,15. Various creep models have been developed to characterize the deformation behavior of anchoring system. These models simulate the coupled interaction between the anchor bolt and the rock-soil masses15,16,17. Time-dependent models have been proposed to predict the service performance of anchor bolts18,19,20. Studies on anchoring systems have shown that the primary cause of deterioration in the service performance of anchor bolts is the time-dependent deformation (creep) of rock or soil due to external environmental factors9,21. Therefore, it is reasonable to establish a connection between the anchor bolt stress and the geotechnical hydrothermal effects. Researchers have developed creep models for anchor bolt-soil systems that consider the influence of water content to evaluate the long-term serviceability of anchor bolts22. Furthermore, a coupled model has been developed to consider damage-stress loss in prestressed anchor cables caused by the wet-dry environment23. However, previous studies have overlooked the actual variations in geotechnical temperature and humidity, as well as the long-term stress development of anchor rods in hydrothermal environments. This limits the accurate assessment of the long-term durability and service performance of anchor bolts.

The unprecedented increase in human modification of natural environments, along with the complexity of geological conditions in engineering construction and the growing fragility of the ecological environment, the case in point is the consecutive construction of projects in western China, including the Sichuan-Tibet Railway and Qinghai-Tibet Expressway24. The future utilization of slope anchoring engineering is anticipated to rise, especially for the maintenance or remediation of existing anchored structures. Previous studies have primarily concentrated on enhancing the protective performance of anchor bolts and prolonging their service life through material enhancements and structural improvements, including the development of energy-absorbing anchor bolts, carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) anchor bolts, and basalt fiber reinforced polymer (BFRP) anchor bolts. Negative Poisson’s ratio(NPR) material has been utilized to enhance the microstructure of steel25,26,27,28. However, the interaction between anchor bolts and rock-soil undergoes a multi-year adjustment process before reaching stability. Assessing the stability of rock-soil and the effectiveness of anchoring cannot be achieved in a short period29. This is particularly evident for water-sensitive loess, which experiences long-term temperature and humidity fluctuations in natural environments30. Therefore, concerning sustainable development, the long-term monitoring of anchor bolt stress can enhance monitoring strategies for managing landslide risks in loess areas. Stress information from the anchor system also aids in understanding the stress transfer behavior of rock or soil31. Furthermore, the time-dependent models for accurate prediction of anchor service performance, which is closely related to complex environmental conditions, have not been involved, especially for in-situ measurement.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the long-term serviceability of anchor bolts applied as the protection structure for the loess slope. Taking the highway in the Linxia City of Gansu Province as the study project, the newly generated loess slopes protected by anchors have been subjected to frequent hydrothermal fluctuations and wide shallow failures. A typical loess cut slope was selected for on-site monitoring. The humidity, temperature characteristics, and anchor stress development of this monitoring slope for four years (2017–2021) are presented and analyzed. Furthermore, a time-dependent mathematical model for anchor bolt stress was established according to hydrothermal environment process for assessing the durability of anchor bolt and long-term safety of slopes over the next 30 years under variable climatic conditions. This research offers insights into the long-term mechanical response of anchor bolts in loess slopes and contributes to the prediction and assessment of their long-term service performance.

Materials and methods

Engineering background

The study area is situated in Linxia City, Gansu Province, China (35°28′43″N, 103°02′27″E). Located in the southwestern of the Loess Plateau (Fig. 1), this region is a transition zone between the Loess Plateau and the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. The area has an elevation of around 2500 m and is characterized by abundant precipitation, significant diurnal temperature differences, and periodic fluctuations in environmental temperature and humidity. The annual average temperature is about 5.6 °C and the annual relative humidity is 62%. In the coldest month (January), the average temperature is -8.6 °C, while in the hottest month (July), it reaches 15.3 °C. Figure 2 shows the annual precipitation and the atmospheric temperature in the study region, with an average annual precipitation of about 900 mm and uneven distribution throughout the year. As shown, precipitation is concentrated between June and September, accounting for 80% of the total precipitation. Precipitation is minimal in December and January, usually less than 20 mm. The average annual evaporation is 620 mm, with a wind speed of 1.61 m/s, frost-free period of 137 days.

Location, section, and monitoring scheme of the case loess slope. Maps were produced by co-authors using ArcGIS ArcMap 10.8 software (https://www.arcgis.com/index.html).

During highway construction, numerous cutting slopes were formed in the loess terrain. Typically, the reinforcement measures for these slopes involve a combination of full-length bond grouted anchor bolts and reinforced concrete frame beams. These measures are capable of withstanding various load combinations, including tension, compression, shear, and bending12. Investigation studies have revealed serious damaged to numerous slopes in the project caused by failures in the anchor protection system. As shown in Fig. 3, mainly manifested as anchor bolts pullout, frame beam fracture, dislocation, and slope collapse.

The studied high-cutting loess slope is located in Linxia City on the Shuangda (Shuangcheng to DaliJia) Expressway. The monitored slope was conducted on a five-stage slope, with a single-stage slope height is 8 m and a total height is 40 m. The 1st to 4th stage slope is protected using precast frame beams and anchor bolts, while the 5th stage slope is protected using concrete retaining wall with a slope ratio of 1:0.5. The anchors are full-length bond grouted anchor bolts, utilizing Q235 threaded reinforcing bars with a length of 10 m, a diameter of 22 mm, an elastic modulus of 210 GPa, and a yield strength of 235 MPa. The anchors are vertically spaced 2 m apart and inclined at 25° to the horizontal. Each stage slope has four longitudinally installed anchor.

Undisturbed loess samples were obtained at a depth of 1.5 m during slope excavation and transported to the laboratory for testing the physical and mechanical properties (Table 1), according to the "Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering (JTG 3430—2020)". Figure 4 shows the particle size distribution (based on the Bettersize 2000 fully automatic laser particle size analyzer), X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (based on the PANalytical Empyrean instrument), and microstructural morphology (based on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with the Quanta 450 FEG instrument) of the tested loess. The particle size distribution reveals that the samples are composed of silt-sized particles (85.2%, diameters 0.002 to 0.075 mm) primarily, with smaller amounts of clay-sized particles (5.9%, diameters under 0.002 mm) and sand-sized particles (8.9%, diameters above 0.075 mm). The XRD pattern indicates that the main mineral constituents are quartz, illite, calcite, and chlorite, with clay minerals accounting for 39.6%. SEM micrographs depict loosely arranged particles with clay particles adhering to the surface of silt particles or forming clusters that connect neighboring silt particles, thereby existing relatively large pores between loess particles. According to the standardized classification criteria for soil samples, the tested loess is classified as low plasticity silt (ML).

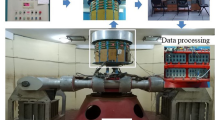

Automatic data acquisition

A comprehensive sensing system for moisture, thermal, and stress was installed on the slope to assess the long-term slope stability. The monitoring system comprises five components: sensing layer, acquisition layer, transmission layer, storage layer, and user layer (Fig. 5). The sensing layer monitors the health status of the slope using multi-sources of information, such as temperature, humidity, stress, rainfall, and atmospheric sensors. The acquisition and transmission layer uses data cables to transfer the monitoring information to the data collection box on the slope platform, functioning in a manner similar to a modem. It receives data from the sensor and transmits it to the remote server via the Internet. The transmission layer utilizes GPRS based on the TCP/IP protocol to achieve wireless remote network transmission of data. The collected data is stored on a data server, which is accessible to authorized users for online access, retrieval, and responsive to terminal requests. The user layer serves as the slope remote control and operation system. It enables the analysis and processing of data collected by the acquisition layer to promptly capture the dynamic changes in the overall state of the monitored slope. The data acquisition and transmission modules are powered by a solar energy system, which ensures the self-powering drive of the monitoring system and guarantees a lifespan of over 5 years.

To assess the water, heat environment, and stress conditions of the loess slope, three monitoring points were selected on each stage slope. These points were located at vertical distances of 2 m (Lower slope), 5 m (Middle slope), and 7 m (Upper slope) from the toe platform. At each monitoring point, temperature and humidity sensors (Type: MS-10) were vertically embedded at depths of 0.2 m, 0.5 m, 1.2 m, and 2.0 m. The sensors measured volumetric water content (0–100%, ± 0.2% accuracy) and temperature (-40–80℃, ± 0.5℃ accuracy). VWR vibrating wire stress gauges were installed at 2 m, 5 m, and 8 m depths on 10 m anchor bolts (Fig. 1), provided highly stable and accurate long-term stress data. The gauges had a 0–100 MPa measurement range with 0.1% F.S. accuracy, and measurement points were assigned as S1–S9. A tipping bucket rain gauge (0.01–4.00 mm/min) and a meteorological station on the slope top platform recorded atmospheric precipitation, temperature, humidity, and evaporation. Manual readings were taken within two weeks during and after the construction period. All monitoring device cables were connected to a 48-channel recorder on the slope platform at 10:00 on November 26, 2017. The recording frequency was set to 1 h, ensuring stable operation. The remote monitoring system has accumulated over 1 million data points in the past 50 months. A detailed analysis was conducted on the third stage slope of the Site 1 section (Fig. 1) within the current monitoring systems.

Results and analysis

The temporal variation of temperature and humidity on slope

Precipitation, temperature, and humidity in the natural environment affect the hydro-thermal migration of the slope. Figure 6 shows the temporal curves of temperature and humidity at different depths of the middle slope during the monitoring period. Observations indicate that the temperature and humidity of the slope increase gradually from January to August each year, and then decrease from August to the following January. The temperature and humidity curves of the slope loess exhibit periodic distribution with similar cycle periods, which conform to the sinusoidal model (Eq. (1) and (2)). This pattern generally corresponds to the variations in atmospheric temperature and precipitation, suggesting that the shallow loess of the slope experiences annual wet-dry cycles caused by external hydrological environment. Moreover, the temperature and humidity of the loess near the slope surface exhibit more pronounced fluctuations and a distinct “sawtooth waveform” phenomenon, while variations in deeper soil are relatively gentle. This indicates that the surface soil is more sensitive to atmospheric temperature and rainfall, engaging in immediate energy exchange with the atmospheric environment.

where T and H represent loess temperature and humidity; t represents measurement time, T0, H0, tT, tH, λT, and λH are model parameters, E represents fluctuation amplitude.

For the reasonable to compare the variation in the humidity and temperature for loess slope, four observation periods were obtained based on monitoring data, during which January 1st to December 31st each year is considered a complete observation period. Table 2 summarizes the soil temperature and humidity for the second observation period, i.e., from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019, including the maximum and minimum values and their corresponding time lags. As shown, the maximum soil temperature decreases with depth, while the minimum temperature increases with depth. This indicates that the amplitude of temperature fluctuations decreases with depth, suggesting a diminishing influence of atmospheric temperature on deeper soil layers. Within the 1.2 m depth, the maximum humidity of the slope decreases with depth, whereas the minimum humidity increases. In the 2.0 m depth, the initial humidity is relatively high, and it shows higher humidity peaks during the monitored period but with a small fluctuation. This suggests that the fluctuation amplitude of slope humidity decreases with depth, indicating a weakening influence in the impact of rainfall and evaporation. The higher initial water content at a depth of 2.0 m may be related to groundwater migration and the relatively high hydraulic conductivity of deeper loess. Additionally, the permeability and evaporation rates of the loess gradually decrease with depth, resulting in more stable moisture migration and temperature gradients. These findings are consistent with previous observations32. The monitoring results also indicate a consistent time lag of approximately 30 days between humidity and temperature at the same depth, regardless of depth variation. This is induced by matric suction from the temperature gradient within the slope, along with the direct influence of rainfall on the internal humidity environment33.

Significant spatial variations in hydrothermal characteristics were observed along the slope surface during the monitoring period. The upper slope experiences more pronounced fluctuations in hydro-thermal due to direct influences from rainfall and evaporation. The temperature and humidity variations on the slope followed the pattern of upper slope > lower slope > middle slope. This implies that the micro-topography of the slope influences the water-heat dynamics of the loess. The middle slope is more prone to surface runoff and insufficient infiltration, resulting in the smallest and relatively uniform distribution of soil temperature and humidity. This suggests that the the upper and lower slope positions expose the soil to more intense wet-dry cycle, which can weaken loess strength and erosion resistance, making it susceptible to rainfall erosion. The significant wet-dry cycle effect corresponds to the shallow failure observed in the field investigation of the loess slope, which mainly involves top spalling and bottom erosion (Fig. 7). Previous studies have also indicated that the terrain (slope gradient and position) affects the annual dynamics of soil temperature and humidity, leading to more severe erosion occurring on lower slopes. This is attributed to intensified rainfall scouring actions and stress concentration-induced soil structure loosening34,35. In summary, the hydrothermal effect of the loess presents depth-dependent lag and significant spatiotemporal variability on the slope surface. During the long-term water-heat coupling on the slope, soil degradation can increase the load on anchor bolts and reduce their service performance, further reducing the long-term slope stability.

The temporal variation of anchor bolt axial force

Installed anchor bolts and the surrounding soil formed a unified system to resist external loads. Therefore, loess deformation and anchor stress occur concurrently due to hydro-thermal effects. Thermal calibration was performed on all anchor stress gauges to eliminate temperature stresses. Figure 8 depicts the temporal variation of axial forces in the anchor bolts on the slope. It is evident that anchor axial forces significantly increase within the 5 months of installation, which is primarily attributed to the soil unloading deformation due to excavation. There are variations in axial force increments at different monitoring points, ranging from a maximum axial force of 18.07 kN (S2) to a minimum axial force of -0.95 kN (S1). This difference is attributed to the varying plastic zones, unloading damage degrees of the slope at different positions during construction, and the non-uniform distribution of stress caused by uneven geological conditions. After 5 months of anchor installation, the growth rate of axial force of the anchor bolts slows down, indicating a gradual stabilization of the energy released by excavation unloading. Throughout the subsequent operational period, fluctuations in the axial forces of all measuring points are recorded, with maximum values occurring in August and minimum values in January each year. Similar patterns of axial force growth have been reported in previous studies36,37.

Figure 9 illustrates the variations of the axial force peaks (maximum values) and valleys (minimum values) in the time evolution curve of the anchor bolts. The results show a gradual increase in the maximum and minimum values of axial forces at all measurement points. With the increase in the service time of the anchor bolts, the upward trend of the maximum and minimum axial forces slows down. For example, S1 experienced increases of 7.98 kN, 3.63 kN, and 2.12 kN at the three peak values of the axial force–time curve, with an average annual growth of 4.57 kN. However, the growth rates decreased by 45.5% and 58.6%, respectively. This indicates that the growth rate of axial forces in the anchor bolts tends to stabilize over time, following a pattern described by the negative exponential function (Eq. (3)). Therefore, it can be concluded that the development of anchor axial forces exhibits time dependence. After 4 years of operation, the maximum axial forces increased by 180.4% (S1), 51.8% (S2), and 27.5% (S3) in the upper slope; meanwhile, the increased by 133.8% (S7), 122.9% (S8), and 81.6% (S9) in the lower slope. This indicates that with increasing depth of the anchor measurement point, the increment of axial forces decreases. Additionally, the axial force near the slope’s surface exhibits a more pronounced fluctuation amplitude, and the variation of axial force with depth aligns with the patterns of temperature and humidity changes. This suggests that soil temperature and humidity play a role in inducing the annual increment of axial force. However, at the middle slope, the maximum axial forces increased by 22.8% (S4), 31.5% (S5), and 43.6% (S6), markedly lower than the recorded at the upper and lower slopes. At point S4, the axial forces transition from tensile to compressive stress during their evolution, consistent with similar stress characteristics observed in previous field tests36. Furthermore, it was observed that the peaks and valleys of the axial force exhibited time delays as the burial depth increased, resembling the patterns seen in soil temperature and humidity also. Thus, the spatiotemporal evolution of axial force in the anchor bolts can be inferred from the slope temperature and humidity measurement results.

where S represents the axial force of anchor bolts, t represents the service time of anchor bolts, k0, α and s0 are model parameters.

Relationship between axial force and slope temperature and humidity

The relationship between anchor bolt axial force and the average temperature and humidity at various monitoring points (from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019) is depicted in Fig. 10. All monitoring data were normalized to eliminate the influence of data types. The results indicate a significant positive correlation between axial force and both slope temperature and humidity. Specifically, an increase in slope temperature and humidity leads to an increase in anchor axial force, while a decrease in slope temperature and humidity results in a corresponding decrease in axial force. Therefore, separate linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between anchor axial force and soil temperature as well as humidity. For upper slope, the linear correlation coefficient between axial force and average slope humidity is greater than 0.7, reaching a maximum of 0.791 (S2), while the coefficient between axial force and average slope temperature is greater than 0.65, with a maximum of 0.839 (S2). For lower slope, the maximum linear correlation coefficient between axial force and average slope temperature and humidity is 0.854 (S7), while the minimum is 0.395 (S9). Except for the S9 point, the correlation between anchor axial force and slope temperature as well as humidity is strong at the other measurement points.

The analysis suggests that variations in slope hydro-thermal, induced by the atmospheric environment, lead to energy conversion between the atmosphere and the loess. This leads to minor cyclic elastic deformation of the slope, characterized by soil particle shrinkage and expansion38,39. With increasing atmospheric temperature, energy is transferred from the atmosphere to the interior of the slope. The loess absorbs this energy, causing thermal expansion of soil particles. Conversely, as atmospheric temperature decreases, energy transfers from the slope to the atmosphere, and the soil releases energy, resulting in particle contraction. Similarly, as slope humidity increases, soil particles absorb moisture, increasing the thickness of the bonding water film between soil particles, thereby causing soil expansion. Conversely, as soil humidity decreases, matric suction between soil particles increases, resulting in particle attraction and soil contraction40. The repeated contraction and expansion of soil particles cause cyclic deformation of the slope. This deformation, in turn, induces micro-strain cycles in the anchor bolts, ultimately resulting in annual cyclic fluctuation of anchor axial forces. However, it is observed that the peak values of axial forces show an annual increasing trend. The driving mechanism for this phenomenon may be the degradation of soil mechanical properties induced by the wet-dry cycles. Repeated fluctuations in temperature and humidity cause the bonds between loess particles to gradually fracture due to the cyclic stress changes. This leads to a reduction in the soil’s elastic modulus and shear strength. As a result, the soil undergoes irreversible plastic deformation (creep) in the shallow slope38. Ultimately, the anchor axial forces exhibit periodic fluctuating growth under the long-term hydro-thermal effects. The correlation coefficient between axial force and slope temperature is higher than humidity. This could be attributed to the faster energy exchange between the slope and the atmosphere compared to water migration. Additionally, a strong linear correlation between soil temperature and humidity was observed, which has been confirmed in numerous studies39.

The anchor bolts monitoring points near the slope surface show more significant fluctuations in axial force, which can be attributed to the reduced energy exchange between the slope and the atmosphere as the burial depth increases. As mentioned earlier, long-term thermal and moisture coupling leads to the deterioration of the soil’s mechanical properties, resulting in increased plastic deformation. This leads to larger annual increments of tensile force for anchor bolts near the slope surface. Deep soil possesses effective thermal insulation and impermeability properties, resulting in smaller temperature and humidity fluctuations and, consequently, less elastic cyclic deformation in the soil. The difference in anchor axial force between the upper slope and lower slope may be attributed to the greater soil plastic deformation induced by temperature and humidity at the upper slope. The middle slope shows a relatively weak correlation between axial force and temperature/humidity. This is likely due to lower temperature and humidity variations (Table 2). Anchor axial force increment decreases with depth at the middle slope, suggesting influences from slope gradient, unloading level, and non-uniform soil deformation. Less shallow soil deformation at the middle slope compared to the upper slope results in relative surface soil compression at the middle slope, leading to compression at point S4.

The spatial distribution of anchor bolt axial force

This study assumes that the tensile stresses at the anchor head and anchor toe of fully bonded grouted anchor bolts are zero and constant over time. Figure 11 illustrates the spatial distribution of anchor axial forces at different slope positions. The axial forces exhibit fluctuations in February and August of each year, with lower values observed in February than in August. The peak axial forces in the anchor bolts at the upper and lower slope consistently occur at depths of 3–5 m, whereas the peak value at the middle slope is at depths of 6–8 m. This may be related to potential sliding zones from long-term creep deformation of the loess. The tensile forces in the anchor bolts are transferred to the stable loess layer through frictional resistance between the anchorage section and the surrounding soil41. When relative displacement occurs between the anchor body and the soil, shear stresses are generated in the anchor bolts, as shown in Fig. 12. At the upper and lower slope, positive shear stresses are present from 0–4 m along the slope surface, indicating that the deformation of the surrounding soil exceeds the self-deformation of the anchor body. Negative shear stresses are observed in the range of 4–10 m, indicating that the deformation of the surrounding soil is less than the anchor self-deformation. At the middle slope, the anchor bolts experience positive shear stresses in the range of 2–7 m, while the nearby soil near the slope surface and the anchor bolts from 7–10 m experience negative shear stresses. As the monitoring time increases, the shear stresses at the same monitoring point progressively rise. This is attributed to the repeated wet-dry cycles, resulting in a decrease in the elastic modulus and strength of the loess, consequently increasing the load transferred from the soil to the anchor bolts.

Based on field tests, Freeman introduced the concept of the “neutral point” for anchor reinforcement in rock-soil masses42. The neutral point is defined as the location where the shear stress in the anchor bolt is zero. Based on this, the anchor bolt is divided into the pull section and the anchored section (Fig. 13a). Thus, the neutral point of the anchor bolt is significant in determining the potential sliding zone of slope. Observations indicate that variations in slope temperature and humidity do not affect the neutral point of the anchor bolt. Based on the shear stress distribution in the anchor bolts, a schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of shallow failure of the loess slope protected by anchor bolts under long-term hydrothermal effect is presented (Fig. 13b). The results show that during excavation unloading and subsequent long-term hydrothermal coupling, the potential sliding zones at the upper and lower slope are shallow, while the potential sliding zone in the middle slope is deeper. This forms the retrogressive shallow landslide pattern, with an additional risk of loess surface sliding in the middle slope.

Time-dependency model for axial force of anchor bolt

Establishment of time-dependency mathematical model

The stress state of anchor bolts is a crucial focus in long-term safety studies of loess cut slopes reinforced with anchor bolts. As a protective system that prevents slope sliding, the stress condition of anchor bolts directly affects the overall safety and stability of the slope. Specifically, the axial force in the anchor bolts is commonly used to assess and provide early warnings regarding the slope’s safety condition31,43. Deciphering the principles governing the evolution of anchor axial forces allows for understanding the historical trajectory of axial force growth under slope hydrological conditions and predicting future trends. Given that the stress in anchor bolts is not yet stable during the construction and operational phases of the slope, it is crucial to scientifically assess the long-term mechanical behavior of the slope, which is influenced by environmental temperature and humidity, rainfall, and soil creep. This assessment is essential for evaluating the anchor safety and predicting their performance.

A time-dependent model for the development of anchor axial forces is established based on the evolutionary characteristics of the monitored slope’s axial force time-history curve and long-term temperature and humidity feedback. The model function (Eq. (4)) comprises the negative exponential function and the sine function. The first part of the model represents the annual increase in anchor bolt axial forces over time, resulting from the degradation of soil mechanical properties and soil creep (plastic deformation) caused by the coupling of shallow soil temperature and humidity. The second part of the model accounts for the periodic fluctuations in anchor bolt axial forces over time, resulting from the cyclic deformation (elastic deformation) of the slope’s shallow soil induced by temperature and humidity fluctuations and seasonal water migration. The time-dependent mathematical model for anchor bolt axial forces is depicted in Fig. 14.

where S(t) represents the axial force of the anchor bolt at time t, t denotes the service time of anchor bolts. The coefficients s0, k1, α, k2, t0, and λ are fitting parameters of the model. Parameter s0 is associated with the initial axial force of the anchor bolts to the reinforced slope during the construction period. The value of s0 is influenced by slope height, unloading level, soil properties, and the anchor bolt angle. Parameters k1 and α in the model are shape parameters that affect the morphological characteristics of the temporal curve of the axial force. k1 represents the post-reinforcement increase in axial force, with a larger value of k1 corresponding to a greater increase in axial force. α represents the time needed for the axial force to stabilize, and a larger α leads to a shorter stabilization time for the axial force. Both k1 and α collectively influence the growth rate of the axial force, with larger k1 values and smaller α values resulting in a higher rate of axial force growth and a greater time-dependence evolution of the axial force. Parameter k2 represents the fluctuation amplitude of the axial force in the anchor bolts due to the periodic cycles in temperature and humidity of the surface loess. Greater cycles in temperature and humidity in the loess result in a higher value of k2. Parameter t0 represents the time difference (in days) between the peak axial force and the corresponding peak temperature/humidity within each cycle. Parameter λ represents the half period (in days) in the time-dependency model.

Application of time-dependency model for axial force of anchor bolt

The axial force of anchor bolts was selected as the optimization objective based on the distribution characteristics and long-term evolution patterns observed in slope monitoring data. An adaptive fitting regression analysis was performed in MATLAB using the previously mentioned axial force–time dependency model to determine the coefficients of the time-dependent mathematical model for the axial force. Table 3 presents the results of the adaptive fitting regression and the coefficient of determination (R2) for the axial force–time mathematical models at various measurement points. The fitting coefficients R2 for all measurement points, except S3 (R2 = 0.7034), are greater than 0.9, suggesting that the established model accurately captures the temporal evolution characteristics of anchor axial force. According to the morphological characteristics of the fitting curves, the variation of anchor axial force can be categorized into three types: (I) Initially, the axial force is relatively low, with a gradual increase over time until it stabilizes during monitoring, showing a slight increment from the initial to the final force. The time-dependent model for category I anchor bolts demonstrates relatively small k1 and large α values. (II) Initially, the axial force is relatively high, increasing rapidly over time without stabilizing during monitoring, resulting in significant variation in the axial force peak. The time-dependent model for category II anchor bolts features large k1 and small α values. (III) The types of category III anchor axial force lie between category I and II. Previous studies obtained statistical data on anchor bolt axial force growth through laboratory test and in-situ monitoring. The evolution patterns of axial force were classified as stable, slow growth, and accelerated growth44,45. These classifications closely resemble the anchor axial force patterns proposed in this paper, which demonstrates the feasibility of the established time-dependent model.

Furthermore, it was observed that axial force models near the slope surface and potential sliding zones have larger k2 values, while those at the distal end from the slope surface have smaller k2. This indicates that the anchor bolt axial force, which is more sensitive to external environmental factors, shows significant differences in peak and valley amplitudes. The reason is that anchor bolts near the slope surface and sliding zones experience greater exposure to rainfall and evaporation, leading to more pronounced variations in soil temperature and humidity. The greater fluctuations in temperature and humidity result in more noticeable axial force fluctuation, which appear to reinforce the correlation between anchor bolt axial force and slope temperature and humidity.

The development of anchor axial force over a 30-year service period was predicted using a time-dependent mathematical model based on regression analysis. The long-term growth characteristics of axial force in slope protection were analyzed. The predicted axial force was then compared with the early warning axial force during slope instability to assess the long-term service performance of the anchor bolts in service.

By differentiating the time-dependent model, we obtain:

Let \(\frac{{{\text{d}}S(t)}}{{{\text{d}}t}} = 0\), the differentiations are performed within segmented intervals [0, 365], [365, 730], …, [365 × (n-1), 365 × n]. The stagnation points, t1, t2, …, tn, are obtained by evaluating the differentiations. Subsequently, by substituting the stagnation points into Eq. (4), the predicted values for the maximum and minimum anchor bolt axial forces can be calculated for different time periods.

Figure 15 illustrates the predicted curves of anchor axial force at each monitoring point throughout the service life. The graph shows a rapid increase in axial force during the first five years of service, accounting for approximately 90% of the total growth. However, the rate of axial force growth slows down between 5 and 10 years of service, and it stabilizes after 15 years of service. The overall behavior of anchor axial forces shows a downward compression deformation trend, which is consistent with the results of the mechanical analysis and the potential failure modes of anchor system. The development trend of axial force reveals that anchor bolts at measurement points S2, S8, and S6 exhibit significant growth with the increase in service life. This indicates that the hydrothermal effects of the soil persistently cause creep in the slope during its operational period, resulting in a continuous increase in anchor axial force, especially near potential sliding zones. In contrast, the axial force increment at S3 and S9 is relatively small, suggesting that the regions farther away from the slope surface experience less hydrothermal effects. Furthermore, S4 shows a relatively small increment in axial force, and the minimum value undergoes a transition from compressive stress to tensile stress in the sixth year of service. This further highlights the complexity of the interaction between soil temperature-humidity conditions and anchor support in the loess slope. In previous studies, Sun46 used the presurvey-support vector machine (PSVM) method to determine the warning thresholds for anchor bolts in several cutting slopes in the study area. These thresholds were calculated using the inverse calculation at a slope stability coefficient of 1.30, indicating an average alert value of 50 kN for axial force. The predictive results of this study indicate that all measurement points are below the instability warning threshold for the slope. This implies that the existing hydrothermal reactions do not affect the service performance of the anchor bolts, and the overall structural integrity of the slope tends to remain safe. It should be noted that the 30-year prediction closely aligns with the meteorological conditions during the existing monitoring period. However, if more severe extreme weather conditions occur beyond the monitoring period, they may result in increased forces on the anchor bolts.

Sensitivity analysis of time-dependency model

The observed fluctuation of anchor axial force and its relationship with the cyclic variations in slope loess temperature and humidity reflect the response of axial force to hydrothermal effect in the shallow loess. Specifically, it relates to the elastic–plastic deformation of the slope resulting from repeated soil expansion and contraction. The fluctuations magnitude and growth rate of axial force depend on environmental changes. This relationship can be quantified by considering the cyclic amplitude and lower limit values in the temperature and humidity variation. The cyclic amplitude (EH and ET) and lower limit values (WH and WT) of temperature and humidity have been identified as the primary parameters influencing the degradation of loess mechanical performance47. The amplitude of temperature and humidity variations is a crucial parameter indicating the extent of dry–wet cycles in the soil. A higher variation amplitude indicates more significant hydrothermal fluctuations in the slope, due to greater energy exchange between the soil and the atmosphere48. The lower limit values of temperature and humidity represent the minimum levels reached during the cyclic hydrothermal fluctuations in the slope. Lower lower-limit value increases the matric suction in the soil, raising the risk of soil cracking and the potential for plastic deformation that can degrade the strength of shallow soil49. Therefore, higher amplitudes of temperature and humidity variations and lower limit values contribute to the growth of anchor axial forces, leading to cyclic changes their behavior. Ultimately, further efforts can be made to determine the coefficients of the time-dependent model describing anchor bolt axial force.

The variation of anchor axial forces at points S2, S5, and S8 is used to analyze the relationship between model parameters and the amplitude and lower limit values of temperature and humidity in the shallow loess. As mentioned above, the coefficient s0, which is related to excavation unloading and the position of the anchor bolt, is not discussed in this study. The parameter k1 represents the maximum increment and is directly proportional to the variation amplitude, but inversely proportional to the lower limit values of temperature and humidity. The parameter α represents the control parameter for the stabilization time and is directly proportional to the variation amplitude, while inversely proportional to the lower limit values of temperature and humidity. The parameter k2 represents the range of axial force periodic fluctuations and is directly proportional to the variation amplitude of temperature and humidity. The parameter λ represents the cycle period of the axial force and is directly proportional to the cycle periods of temperature and humidity. Subsequently, the relationship between temperature, humidity, and the time-dependent coefficients in the axial force model can be established. The relationship is depicted in Fig. 16. The results indicate a positive linear correlation between the coefficient k1 and \(\sqrt {E_{T} E_{H} /W_{T} W_{H} }\), and a negative linear correlation between α and \(\sqrt {E_{T} E_{H} /W_{T} W_{H} }\). In contrast, k2 shows a positive linear correlation with \(\sqrt {E_{T} E_{H} }\). Ultimately, the coefficients of the time-dependent model can be determined by utilizing Eq. (6)-(9). Therefore, valuable information about the service performance and maintenance timing of anchor bolts can be obtained by monitoring the temperature and humidity in the loess slope. It should be noted that the determination of the hydrothermal paths in this study is based on the average cyclic amplitude and lower limit values of temperature and humidity fluctuations within the 2 m depth range of the loess.

where ET represents cycle amplitude of temperature, EH represents cycle amplitude of humidity, WT represents lower limit value of temperature, WH represents lower limit value of humidity, λT represents half cycle period of temperature, λH represents half cycle period of humidity. Since the axial force of the anchor bolt corresponds to the temperature and humidity period, the parameter λ is fixed at 180 (in days).

Regression analysis was conducted between the calculated and measured values, and the results are presented in Fig. 17. The model demonstrated excellent performance in generating axial force measurements, with coefficients of determination(R2) of 0.889 (S2), 0.961 (S5), and 0.889 (S8), and root mean square errors (RMSE) of 1.59 kN (S2), 0.75 kN (S5), and 1.94 kN (S8). Therefore, the established time-dependent model has good applicability in simulating the evolution of anchor axial force in loess slope under long-term hydrothermal effect.

The future global climate remains uncertain. Recent local monitoring records have highlighted a significant increase in regional precipitation50. Climate models project a 3.5℃ increase in the global average temperature by the end of this century39. The simulation in anchor axial forces in this study rely on the cyclic amplitude and lower limit values of slope hydrothermal fluctuations. Therefore, the established model for anchor axial forces serves as a tool for investigating the potential impact of climate change. It should be noted that the model has limitations in directly comparing the specific influence of temperature and humidity on axial forces. In the future, more detailed analysis of the differential effects of temperature and humidity on anchor forces will be conducted to enhance the time-dependent mathematical model. Furthermore, the time-dependent model does not account for the long-term stability of the entire slope resulting from the growth of individual anchor stresses. This may necessitate further numerical simulation research. It is important to consider various factors such as slope gradient, soil creep, unloading levels, and chemical corrosion, along with their impact on anchor stress, to expand the applicability of the model.

Conclusion

-

1.

The temperature and humidity of the slope shallow loess exhibit periodic fluctuations and follow an annual cycle, resulting in wet-dry cycles in the shallow loess. The amplitude of hydrothermal fluctuations decreases gradually with depth. The lateral water migration within the slope results in higher water fluctuations at the upper and lower slopes compared to the middle slope. Slope humidity and temperature have a time lag of approximately 30 days.

-

2.

Anchor bolt stress reaches maximum value in the summer and minimum value in the winter, showing an annual fluctuating growth pattern. Interannual fluctuation of axial force results from the elastic deformation of loess. The irreversible increase in axial forces within each period is attributed to the loess plastic deformation caused by long-term hydrothermal effects, degradation of mechanical strength, and deformation resistance capacity. The differential hydrothermal environment in depth leads to a more significant growth amplitude of anchor axial force near the slope surface.

-

3.

A time-dependent model is established for the anchor axial force, combining exponential and sine functions, based on the evolutionary pattern of axial forces. The cyclic growth of axial force is classified into three categories based on the morphological parameters of the model. The model parameters can be determined by considering the amplitude, lower limit values, and periods of temperature and humidity variations in the shallow loess of the slope.

-

4.

The time-dependent model provides an effective method to predict the development trend of anchor serviceability in different hydrothermal environments. Within 30 years of slope service, the anchor axial force remains below the landslide threshold, ensuring the operation safety of the anchor bolt and the early reinforcement requirements of the slope. The predicted results offer valuable insights for assessing the durability of anchor bolt protection slope and determining the optimal maintenance timing.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Ehrlich, M. & Silva, R. C. Behavior of a 31 m high excavation supported by anchoring and nailing in residual soil of gneiss. Eng. Geol. 191, 48–60 (2015).

Grasselli, G. 3D Behaviour of bolted rock joints: experimental and numerical study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 42, 13–24 (2005).

Lyu, J. et al. Analysis of the impact of the combined use of rebar bolts and FRP bolts in the roadway enclosure. Sci. Rep. 13, 19630 (2023).

Lee, W. F. et al. Failure analysis of a highway dip slope slide. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 27, 116–131 (2013).

Rajabian, A., Viswanadham, B. V. S., Ghiassian, H. & Salehzadeh, H. Centrifuge model studies on anchored geosynthetic slopes for coastal shore protection. Geotext. Geomembr. 34, 144–157 (2012).

Wang, L., Hwang, J. H., Luo, Z., Juang, C. H. & Xiao, J. Probabilistic back analysis of slope failure – A case study in Taiwan. Comput. Geotech. 51, 12–23 (2013).

Ma, S., Nemcik, J. & Aziz, N. An analytical model of fully grouted rock bolts subjected to tensile load. Constr. Build. Mat. 49, 519–526 (2013).

Guo, W. & Ma, & Wang.,. Testing Mechanical properties of rock bolt under different supports using fiber bragg grating technology. Sensors 19, 4098 (2019).

Chen, G., Chen, T., Chen, Y., Huang, R. & Liu, M. A new method of predicting the prestress variations in anchored cables with excavation unloading destruction. Eng. Geol. 241, 109–120 (2018).

Singh, P. & Spearing, A. J. S. An improved analytical model for the elastic and plastic strain-hardening shear behaviour of fully grouted rockbolts. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 3909–3925 (2021).

Benmokrane, B. & Ballivy, G. Five-year monitoring of load losses on prestressed cement-grouted rock anchors. Can. Geotech. J. 28, 668–677 (1991).

Blanco Martín, L., Tijani, M., Hadj-Hassen, F. & Noiret, A. Assessment of the bolt-grout interface behaviour of fully grouted rockbolts from laboratory experiments under axial loads. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 63, 50–61 (2013).

Chen, C., Zhu, S., Zhang, G., Mao, F. & Cai, H. Time-dependent load transfer behavior of grouted anchors in laterite. Comput. Geotech. 132, 103969 (2021).

Farmer, I. W. Stress distribution along a resin grouted rock anchor. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. Geomecha. Abstr. 12, 347–351 (1975).

Zhu, S., Chen, C., Zhang, G. & Du, C. Theoretical and experimental investigations of anchoring force loss behavior for prestressed ground anchors. Can. Geotech. J. 59, 1587–1601 (2022).

Li, T., Cai, H., Liu, Bo., Luo, X. & Qian, X. Study on prestress loss and rheological coupling model of anchor cables in expansive soil layers. Chinese J. Rock Mech. Eng. 39, 147–155 (2020).

Zahmatkesh, A. & Choobbasti, A. J. Evaluation of wall deflections and ground surface settlements in deep excavations. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 3055–3063 (2015).

Dong, X. et al. Study on coupling model of anchorage force loess and time-dependent deformation of rock-soil mass. Chinese J. Rock Mech. Eng. 41, 1093–1102 (2022).

Shi, K., Wu, X., Liu, Z. & Dai, S. Coupled calculation model for anchoring force loss in a slope reinforced by a frame beam and anchor cables. Eng. Geol. 260, 105245 (2019).

Yang, M., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, N. Creep behavior of epoxy-bonded anchor system. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 67, 96–103 (2014).

Rajeev, P., Chan, D. & Kodikara, J. Ground–atmosphere interaction modelling for long-term prediction of soil moisture and temperature. Can. Geotech. J. 49, 1059–1073 (2012).

Zhang, G., Chen, C., Zornberg, J. G., Morsy, A. M. & Mao, F. Interface creep behavior of grouted anchors in clayey soils: effect of soil moisture condition. Acta. Geotech. 15, 2159–2177 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Study on damage-stress loss coupling model of rock and prestressed anchor cable in dry-wet environment. Int. J. Mining Sci. Tech. 33, 1451–1467 (2023).

Lan, H. et al. Climate change drives flooding risk increases in the Yellow River Basin. Geo. Sustain. 5, 193–199 (2024).

He, M. et al. Experimental study on the shear performance of quasi-NPR steel bolted rock joints. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15, 350–362 (2023).

Tao, Z., Zhang, H., Chen, Y. & Jiang, C. Support principles of NPR bolt/cable and control techniques of large-deformation disasters. Int. J Mining Sci. Tech. 26, 967–973 (2016).

Zhou, C., Huang, C., Chen, Y., Zhang, W. & Wang, L. Performance of a novel resistant rock bolt with periodic energy absorption and release: theory and experiment. Acta. Geotech. 19, 363–378 (2024).

Zhang, M., Cao, C., Li, G. & Guo, B. Anchorage performance of a new rebar bolt under different surrounding rock strength and borehole depth. Sci. Rep. 14, 9581 (2024).

Chang, Z. et al. Health status evaluation of highway tunnel inverted arch based on variable weight and extension cloud model. Eng. Fail. Anal. 157, 107939 (2024).

Chang, Z. et al. Large-scale field tunnel model experience and time-dependent floor heave induced by humidification. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 145, 105615 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Field investigation of force and displacement within a strata slope using a real-time remote monitoring system. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 552 (2018).

Liu, Y. & Yang, Y. Spatial-temporal variability pattern of multi-depth soil moisture jointly driven by climatic and human factors in China. J. Hydrol. 619, 129313 (2023).

Yoshioka, M., Takakura, S., Ishizawa, T. & Sakai, N. Temporal changes of soil temperature with soil water content in an embankment slope during controlled artificial rainfall experiments. J. Appl. Geophys. 114, 134–145 (2015).

Morbidelli, R., Saltalippi, C., Flammini, A. & Govindaraju, R. S. Role of slope on infiltration: A review. J. Hydrol. 557, 878–886 (2018).

Caplan, J. S. et al. Decadal-scale shifts in soil hydraulic properties as induced by altered precipitation. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau6635 (2019).

Fan, Q., Zhu, H. & Geng, J. Monitoring result analyses of high slope of five-step ship lock in the Three Gorges Project. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 7, 199–206 (2015).

Jingchun, Xu., Junping, Yu., Lijun, Wu. & Yang, Z. Analysis of monitored axial force of anchor in the absence of teperature influence. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 34, 81–86 (2017).

Lan, H. et al. Large scale land reclamation and the effects on hydro-mechanical behavior in loess and loess-derived fill. Eng. Geol. 323, 107241 (2023).

Lan, H. et al. The cyclic expansion and contraction characteristics of a loess slope and implications for slope stability. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 2250 (2020).

Archer, A. & Ng, C. W. W. Effects of temperature and relative humidity on a clay embankment: centrifuge modelling. Géotech. Lett. 8, 138–143 (2018).

Liu, C. H. & Li, Y. Z. Analytical study of the mechanical behavior of fully grouted bolts in bedding rock slopes. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 50, 2413–2423 (2017).

Freeman, T. J. Behaviour of fully bonded rock bolts in the kielder experimental tunnel. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 15, A107 (1978).

Yan, C., Sun, W., Wei, Xu. & Liu, B. Dynamic early warning analysis and safety classification of slope with single sliding plane based on monitoring of fully grounted bolts. China J. Highw. Transp. 31(188–19), 226 (2018).

Wenguang, Fu., Yang, Li. & Feng, D. Integrated study on stability judgment method for grouting anchor tests. Chinese J. Geotech. Eng. 46, 694–704 (2024).

He, M. Real-time remote monitoring and forecasting system for geological disasters of landslides and its engineering application. Chinese J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28, 1081–1090 (2009).

Sun, W. Study of instability mechanism and intelligent pre-warning for cutting slope with soil-rock binary structure. (Chang'an University, Xi'an, Shaanxi, China, https://doi.org/10.26976/d.cnki.gchau.2020.000016). (2021).

Hu, C., Yuan, Y., Mei, Y., Wang, X. & Liu, Z. Comprehensive strength deterioration model of compacted loess exposed to drying-wetting cycles. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 383–398 (2020).

Ye, W., Zhao, Z., Yang, G., Xi, J. & Zhang, Y. Influence of soil moisture state on loess slope spalling hazards. China J. Highw. Transp. 28, 18–24 (2015).

Mu, Q. Y., Dong, H., Liao, H. J., Dang, Y. J. & Zhou, C. Water-retention curves of loess under wetting−drying cycles. Géotech. Lett. 10, 135–140 (2020).

Wang, L. N., Zhu, Q. K., Zhao, W. J. & Zhao, X. K. The drought trend and its relationship with rainfall intensity in the Loess Plateau of China. Nat. Hazard. 77, 479–495 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 42307217, 41927806, 42077265, 42041006), the Basic Research Funds for Central Universities, CHD (grant number: 300102262901), the Research Program of Xinjiang Awua Highway Development Co., Ltd (grant number: AWAGSGCJS-23-ZXFWHT-003). The authors of this article are so grateful to editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on this paper.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (42307217, 41927806, 42077265, 42041006). Basic Research Funds for Central Universities, CHD (300102262901). Research Program of Xinjiang Awua Highway Development Co., Ltd (AWAGSGCJS-23-ZXFWHT-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C.: Data interpretation, review of results, wrote and revised the main manuscript. W.S.: field test and provided the original idea. C.Y.: design of the experiment, project administration. H.L.: project administration, drafting of manuscript. Y.S.: data interpretation, drafting of manuscript. H.B.: data interpretation, drafting of manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, Z., Sun, W., Yan, C. et al. Failure risk study of anchor bolts durability for loess slope under long-term hydro-thermal effect. Sci Rep 15, 177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84106-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84106-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Correlation analysis and comprehensive evaluation of dam safety monitoring at Silin hydropower station

Scientific Reports (2025)