Abstract

Energy hubs, with their diverse regeneration and storage sources, can engage concurrently in energy transfer and storage. It is anticipated that managing the energy of these hubs within energy networks could enhance economic, environmental, and technical metrics. This article explains how electrical and thermal network hubs manage their energy consumption in the context of the multi-criteria objectives of efficiency, sustainability, reliability of the network operator, and operation. The hubs have solar power, a bio-waste unit, and wind turbines among other sustainable energy sources. They have compressed air, heat, and hydrogen storage units installed. Thermal energy is produced by means of a heat pump from electrical energy. Combining heat and power technology is used by both the bio-waste unit and the hydrogen storage unit. Subject to the operating model and reliability restrictions of these networks, the suggested strategy seeks to reduce the overall estimated costs of energy procurement, dependability, and emissions within the designated networks. Additional constraints of the problem encompass the operational model of sources and storages, conceptualized as an energy hub. This plan takes into account uncertainties about demand, energy costs, renewable energy sources, and the availability of network equipment. Reliability is accurately predicted by scenario-based techniques to stochastic optimization. The simultaneous modeling of economic, operational, reliability, and environmental indicators as well as the evaluation of the capabilities of heat pumps, biowaste units, compressed air and hydrogen storage units, and heat pumps in the hub performance are seen to be the new aspects of this approach. In summary, numerical results validate the usefulness of the proposed approach in enhancing the technical and financial aspects of thermal and electrical networks via efficient hub energy management. The incorporation of renewable hubs, equipped with storage units and heat pumps, has led to improvements in the economic, operational, reliability, and environmental conditions by approximately 44.1%, 28–90%, 85.6%, and 72.1% respectively, in comparison to load distribution studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation

One strategy being looked at to cut emissions is the integration of renewable energy sources (RESs) into power systems and energy networks1. These sources encompass wind turbines (WTs) and photovoltaics (PVs), which harness wind speed and solar radiation respectively to generate electricity1. The bio-waste unit is an additional kind of RES (BU). This device produces methane gas from environmental trash, which is then transformed into electrical energy2. Moreover, this kind of unit may generate thermal energy in addition to electrical energy if it is outfitted with combined heat and power (CHP) technology. Since renewable phenomena are by their very nature unpredictable, producing renewable electricity is also unpredictable. Consequently, there could be differences between the results of operations in real time and those obtained from data on projected renewable power. In real-time operation, this might result in an imbalance between output and consumption3. Energy storage systems may adjust both their active and thermal power to make up for changes in renewable power3. Despite the fact that there are many different types of storage units, batteries are extensively employed in most applications due to their superior efficiency. However, these storage units have drawbacks, including capacity limitations, a relatively short lifespan, and high installation costs. Compressed air energy storage (CAES) and hydrogen storage (HS) are two further forms of energy storage. These storage units have an average 75% efficiency, are long-lasting, and are not limited by size4,5. Furthermore, HS could have CHP technology installed, enabling it to generate thermal energy in addition to electrical energy storage. Every one of the above mentioned capabilities is dependent upon the choice of energy management system (EMS)5. In the initial phase of implementing an EMS, diverse sources and storage units can be organized in a coordinated manner, akin to an energy hub (EH), to enhance their efficiency. In this setup, the hub operator can manage the energy of these elements in accordance with its objectives and those of the network operator, by establishing bidirectional coordination with the sources and storage units. This implies that the hub operator maintains communication with various energy network operators. Thus, the hub operator can orchestrate optimal energy management for sources and storage, aligning with its requirements as well as those of the network operator6. It is predicted that the establishment of an appropriate EMS in energy networks, in conjunction with EHs, could constitute a beneficial and effective measure towards enhancing the economic, environmental, and technical conditions of these networks.

Today, energy production is highly dependent on fossil fuels. Fossil fuels, in addition to causing environmental pollution, will run out in the coming years. This can cause social concerns. To solve this problem, organizations operating in the energy sector suggest using renewable resources. However, to access sustainable energy from these resources, it is necessary to use storage devices in addition to the aforementioned resources. In addition, the energy consumed has various types, such as electrical and thermal energy. Some renewable resources are able to produce several types of energy in their output, which increases the efficiency of the resource. Therefore, access to sustainable energy based on renewable resources will be of great importance in many countries in the coming years. This is in line with the promotion of social welfare in relation to energy supply in the coming years. Hence, the academic field should provide appropriate solutions for providing sustainable renewable energy. According to7,8, a suitable solution in relation to the stated issue and the implementation of a high-performance EMS is the aggregation of resources and storage devices. In addition, EHs have high energy efficiency because they manage several different types of energy. For example, in an EH, if a BU is the only supplier of electrical energy, this source operates with an efficiency of about 40%. However, if it is equipped with CHP, the efficiency of the source increases to about 80%2. In addition, the aggregation of resources and storage devices, for example in the form of an EH, can lead to a reduction in the fluctuations of the output power of the hub. Because the storage device is able to compensate for the fluctuations of the power of renewable resources by controlling its power7. In7,8, the operation of resources and storage devices separately is compared with their operation in the form of an integrated system such as a hub. Based on the results of7,8, the integrated model of resources and storage has better capabilities in improving the economic and technical status of energy hubs and networks.

Research background

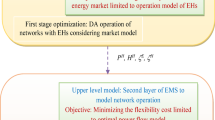

The functioning of EHs in energy networks has been the subject of many published research studies. The hydrogen vehicle (HV) parking lot, electric heat pump (HP), absorption chiller (AC), photovoltaic (PV) module, boiler, hydrogen electrolyzer, and electric, thermal, cooling, and hydrogen storage systems are all included in the unit commitment (UC) in EHs created in9. Here, the natural gas, electricity, and heat inputs of the EH are used to fulfill the demands for hydrogen as well as natural gas, heat, cooling, and power. EHs connected to demand response aggregators are scheduled a day in advance using the method described in10. Photovoltaic and wind, biomass, hydrogen electrolyzers (ELs), combined heat and power (CHP) units, solar heaters, boilers, and electric, thermal, and hydrogen storage systems are some of the renewable energy sources that are being researched. EH has the option to purchase electricity from demand response aggregators in addition to the gas network and the electric grid. Information gap decision theory (IGDT) is utilized as a risk-aware method to manage the uncertainties related to solar heat, electricity price, photovoltaic and wind power, and electric, thermal, and hydrogen demands. Reference11 discusses the optimal load dispatch form for an EH in order to minimize the hub’s total costs, which include costs for CO2 emissions and exploitation. Electric vehicles (EVs), gas boiler, PV arrays, heat storage, CHP unit, and WT are all part of this energy center. A developed technique based on grasshopper search is implemented to cope with future uncertainties in electricity pricing. EV uncertainty is addressed using Monte Carlo simulation (MCS). Furthermore, the suggested model takes into account the thermal and electric demand response (DR) techniques in their whole. In12, the robust optimization approach has been used to address the uncertainty related to the price of power and the dispersed resources of renewable energy. The MCS has been used to discriminate between the integrated charging load of EVs under coordinated and uncoordinated charging modes. A unique Monte-Carlo-based modeling and computational framework for simulating Smart Hub activities is presented in Ref.13, offering a way to thoroughly evaluate the technical and financial feasibility of these activities. The approach takes into consideration driver choice, price inflation, power losses, PV module deterioration, variance in EV adoption, and variability in EVs and charging stations using a mathematical model that is both simple and realistic. For the operation of energy hubs in conjunction with day-ahead and real-time electricity markets, a two-stage stochastic model is presented in14 that accounts for demand, renewable power, and real-time electricity price. The model incorporates value-at-risk, a risk measure, to prevent unnecessary operational expenses in the worst-case scenarios. The operational point of the hub components and the transactions for natural gas and electricity are determined, and a multi-objective optimization problem is created. A novel approach to using EH to thermally integrate a thermomechanical pulp mill and paper machine is presented by the authors of15. To provide the heating requirements of the paper machine, the thermomechanical pulp mill is coupled with an EH that comprises of an electric boiler and a steam generator heat pump. This study integrates load profile prediction, reliability and availability evaluation, and thermo-economic analysis to evaluate the sophisticated, economical design and operation of the EH. A two-level paradigm based on demand unpredictability and RES is provided by16 for the optimal EH planning and operation. To illustrate optimum planning at the primary level and optimal operation at the secondary level, stochastic-probability models are used. Reference17 describes the energy management of thermal and electrical networks in the presence of renewable energy sources. This is done in order to control the networks’ flexibility via flexible pricing services. Renewable sources, bio-waste units, responsive loads, and energy storage are examples of hubs. The bio-waste unit produces electrical energy and heat at the same time. The recommended strategy lessens the difference between the network’s energy expenses and the hub’s flexibility income. The hub flexibility model, the best power flow equations, network flexibility limitations, and the energy hub operating model for resources, storage, and responsive loads all have an impact on it. In reference18, it is discussed how the market clearing price model may be used to include flexible renewable energy houses (EHs) that are outfitted with compressed air, thermal, hydrogen, and wind farms in addition to bio-waste units in the energy market. Hubs are concurrently found in thermal and electrical networks. Using integrated heat and power technologies, the bio-waste unit produces both thermal and electrical energy. Bi-level optimization shapes the suggested design. The research background’s work summary is presented in Table 1.

Research gaps

The following are the main research gaps for the energy management of EHs linked to the network, based on Table 1 and the study background:

-

The bulk of studies have examined how hubs affect the operational and financial elements of energy networks. However, it’s important to recognize that hubs are situated at multiple consumption points within these networks and can contribute significantly to energy transfer and storage. It is predicted that in the event of an N − 1 incident, hubs could offset a substantial proportion of consumer outages, thereby playing a pivotal role in enhancing the network’s reliability. This particular aspect, though crucial, has been less explored in studies, such as the one referenced in15. Furthermore, hubs typically rely on RESs and eco-friendly components. It is anticipated that their integration into the network could reduce emissions caused by the energy supply from centralized production units like power plants. While this issue has been addressed in numerous studies, only a handful, such as the one cited in11, have discussed a mathematical model for assessing the impact of hubs on environmental conditions. This highlights a potential area for further research and exploration. Another noteworthy point is that, enhancing one index does not necessarily result in the improvement of another. For instance, bolstering reliability requires sources within the network to inject high power, which consequently leads to an escalation in energy losses. This emphasizes how important it is for the hubs’ energy management strategy to simultaneously simulate a variety of technical and environmental variables. References11,15 point out that research have not as often addressed this element.

-

RESs come in various forms, including WTs, PV, and BUs. While much of the research has centered on the use of WT and PV, the potential of BU remains relatively unexplored. BUs, by processing environmental waste, can generate electrical energy. Furthermore, if they are outfitted with CHP technology, they have the ability to generate thermal and electrical energy simultaneously. As mentioned in references10,17,18, research has, however, less often evaluated their competence inside EHs. Only the BU’s capacity to generate electrical energy was considered in Ref.10.

-

Predominantly, batteries have been the storage of choice in EHs in most research studies. Despite their high energy efficiency and power density, batteries have certain limitations such as a shorter lifespan, high installation costs, and expensive upgrades for higher capacities18. To address these issues, compressed air and hydrogen storages emerge as viable alternatives to batteries in hubs. These storage options can be constructed at a high capacity, boast a longer lifespan, and maintain a suitable energy efficiency of approximately 75%. Additionally, a fuel cell (FC) is used in hydrogen storage to convert hydrogen into electrical energy. This FC can concurrently create heat energy and electricity if combined heat and power (CHP) technology is coupled with it. However, as references9,10,18 demonstrate, prior research has not paid much attention to the examination of hydrogen storage deployment in hubs. These studies did not take into account the FC’s capability to produce thermal energy. Similarly, the use of CAES has been less commonly considered in studies, as indicated in reference18.

-

Heat pump (HP) can transform electrical energy into thermal energy. This allows it to receive electrical energy from RESs and supply thermal consumers, aligning with environmental improvement efforts. In contrast, conventional thermal producers often rely on fossil fuels for conversion into thermal energy, which contributes to emissions. However, the potential of HP within renewable hubs has been less frequently explored in studies, as indicated in reference12.

Contributions

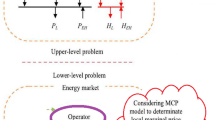

In an effort to close the research gaps indicated in the section above, this work offers an energy management strategy for hubs connected to thermal and electrical networks. As seen in Fig. 1, this method takes network operators’ operational, financial, environmental, and reliability objectives into account. The hubs under consideration are equipped with RESs such as wind, solar, and bio-waste. They also have hydrogen, thermal, and compressed air storage units. To increase energy efficiency, BU and FC are equipped with CHP. HP is utilized for the conversion of electrical energy into thermal energy. In essence, the hubs generate electrical energy through WT, PV, and BU. Thermal energy is supplied from FC, HP, and BU. In the electrical (thermal) section, hydrogen and compressed air (thermal) storage units are utilized. In this scheme, the objective function is designed to consider the multi-criteria objectives of network operators. It is equivalent to the total expected costs associated with the operation, environmental impact, and reliability of electrical and thermal networks. These constraints include equations for optimal power distribution, network reliability restrictions, and the operational model of RESs, storage units, and HPs, all of which are designed to function as an energy hub. The proposed scheme factors in uncertainties related to load, energy price, wind speed, solar radiation, gas production by the BU, and equipment availability within the network. In this study, Scenario-Based Stochastic Optimization (SBSO) is employed for the accurate modeling of reliability indices. This approach is necessary for a thorough examination of reliability indices, as it allows for the exploration of various scenarios of uncertainties related to network equipment availability, load, and renewable power14. The SBSO creates circumstances using the Roulette Wheel Mechanism (RWM) and reduces them using the Simultaneous Backward Method (SBM). The following is a list of this concept’s main advancements and contributions.

-

Storage units in electrical and thermal networks are used for energy management of renewable energy sources. Enhancing these networks’ environmental, operational, economic, and reliable indicators all at once is the aim.

-

Evaluating the performance of compressed air and hydrogen storage units with CHP inside EHs.

-

Evaluation of BU, outfitted with CHP and HP, within the EH to boost energy efficiency.

-

Simultaneous modeling of economic, operational, environmental, and reliability indices.

EHs are a unit integrating renewable and non-renewable resources, storage devices and demand response programs. EH has different types of energy such as electricity, gas and heat in its input and output. This issue is also present in the energy hub used in this article. There are electricity and heat energies in the input and output of the hub. In this design, only renewable resources were used, so that the hubs have low environmental pollution. An important feature of the hub used in this study compared to the research background9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 is the supply of thermal energy from renewable sources. So that according to Fig. 1, BU, FC and HP are thermal energy producers. BU is a renewable source; HP supplies its input electrical energy from renewable sources. FC also receives hydrogen from HT at its input. Hydrogen is also obtained from renewable sources by electrolyzer. This feature is due to the use of CHP in HS and BU. In addition, according to Sect. 1.3, batteries were generally used in hubs. Although this storage device has high efficiency and power density, its useful life is short and it has high installation cost. The hub used in this research uses CAES and HS. These storage devices have long useful life and low installation cost. There is also a good efficiency for them. In addition, HS can be equipped with CHP, which makes HS play a role in providing thermal energy and increase its working efficiency.

There are renewable energy sources in the energy hub. The production power of these sources depends on natural phenomena such as wind speed and solar radiation. The amount of these phenomena is different at various times, so the production power of renewable resources changes according to time. Therefore, the daily load profile and the daily power profile of renewable resources are not the same. Storage is used to cover the gap between the aforementioned profiles so that it can achieve an energy production role for the hub. In this situation, the hub is able to improve the technical and economic status of the network by injecting power into the network. The storage is able to compensate for fluctuations in the power of renewable resources. This can lead to a balance of production and consumption in the hub. In addition, a heat pump was used in the energy hub. This element was used so that the hub could supply its thermal consumption energy with renewable resources. This will result in improving the environmental situation.

The proposed idea is feasible when the smart platform is established in the energy hubs and networks. So that, according to Fig. 1, the hub operator is in two-way communication with the resources and storage devices. The hub elements send their data to the hub operator, the hub operator obtains the optimal active and thermal power scheduling for the resources and storage devices. Of course, the hub operator is also in two-way communication with the energy networks operator. In this coordination between the operators, the network operator reports the optimal active and thermal power scheduling to the hub operator, considering its objective function and the technical constraints of the network. Therefore, the initial introduction to the implementation of the proposed scheme is to create a smart platform in the energy hub and networks.

Paper organization

The formulation of energy management for network-connected hubs is detailed in the second section. The third section presents the modeling of uncertainties, utilizing the SBSO approach. The fourth section discusses the numerical results derived from various case studies. Conclusions are mentioned in the fifth section.

Formulation of the proposed plan

The energy management of renewable energy harvesters (EHs) that use flexible sources, such as compressed air, hydrogen, and thermal storage, is examined in this section. Intelligent electric and thermal networks comprise these EHs. This strategy aims to lower the overall estimated operating costs and emissions while improving the chosen networks’ dependability. The operational model of renewable and flexible sources in the EH format, as well as the optimum power distribution equations in energy networks, set the system’s bounds. Thus, this strategy may be represented mathematically as follows.

Objective function

With the goal of minimizing anticipated operating costs (EOC), environmental costs (EEC), and enhancing reliability costs (ERC) in the electrical and thermal networks, the suggested approach is based on objective function (1). In the first row of (1), the cost of acquiring energy from the upstream network is equivalent to the EOC for the electrical network (first term) and the thermal network (second term)17. The energy price multiplied by the amount of energy sent via the distribution posts yields the cost. The costs linked to emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) as a consequence of the networks’ connection to centralized industrial facilities are shown in the second row19. This means that EEC = EEM×VOEP, anticipated emissions (VOEP) stands for emissions anticipated penalty price. The emissions coefficients of CO2, NOx, and SO2 added together provide the coefficient ρ. ERC, which is introduced in the third row of (1), represents the cost of the customer outages during event N-1. The value of lost load (VOLL in $/MWh) multiplied by the expected energy not provided (EENS) determines this cost for each network20.

In this paper, the objective function includes minimizing the operating cost of energy networks, minimizing environmental pollution, and unfed energy under N-1 event conditions. Energy hubs have various resources and storage devices, so that they can act as energy transfer and storage device. Therefore, by implementing appropriate energy management, it is expected that hubs can play a significant role in improving the economic, technical, and environmental conditions of energy networks. In economic terms, it is expected that hubs can reduce the cost of purchasing energy from upstream networks by injecting power into the network. Renewable hubs, which have very low emissions, can reduce the energy demand in networks by injecting energy into electrical and thermal networks. Therefore, the energy received by these networks from centralized power plants, which are generally based on fossil fuel consumption, is reduced, and environmental conditions are improved. In addition, hubs are generally located at consumption points. If an error occurs in the network, the hubs can feed part of the consumed energy. Therefore, the network can have high reliability. Considering these issues, the main objective of this paper is to investigate the effectiveness of renewable hubs in improving the economic, environmental and reliability functions of energy networks. Therefore, the objective function (1) was selected. Based on this relationship, the objective variables in this paper include the cost function (Cost), power passing through distribution substations (PS and HS), unfed power (PN and HN), emission level (EEM), EENS, reliability cost (ERC), emission cost (EEC) and network operating cost (EOC).

Operation-reliability model of energy networks

Constraints (2)–(16) provide the equations for the optimal power distribution in the thermal and electrical networks. Limitations (2) through (10) provide an explanation of this network’s power flow interactions21,22,23,24,25. More specifically, Eqs. (2) and (4) represent the distribution of thermal power in the thermal nodes and the distribution of active and reactive power in the electrical buses, respectively17,18. Additionally, the models in (5)–(7) represent the thermal power flowing through the pipes and the active and reactive power traveling via the electrical distribution lines, respectively3. The values for the temperature at the slack node and the voltage’s magnitude and angle at the slack bus are given in the constraints (8)–(10). Constraints (11)–(16) detail the limits of the thermal and electrical networks. (11) and (12) in these constraints relate to the temperature limitation at the thermal nodes and the voltage magnitude restriction at the electrical buses, respectively3,17,18. The thermal power limitation traveling through the pipelines and the apparent power restriction traveling through the electrical distribution lines are shown in (13) and (14) accordingly17. In (15) and (16), these limitations for the thermal and electrical distribution posts are also considered18,26,27. In (2)-(16), the parameter u signifies the accessibility of network equipment, including distribution lines and distribution posts, in incident N – 1. A value of 1 (zero) for this parameter denotes the presence (disconnection) of the corresponding equipment in (from) the network during an incident. Reliability constraints are articulated in (17) and (18) for electrical and thermal networks, respectively. These constraints pertain to the limitation of not supplied load in the aforementioned networks20.

Operational model of renewable EHs with storage

The limitations on how EHs28 with flexible and renewable energy sources may operate are outlined in (19)–(39). Constraints (19) and (20) delineate the equilibrium between thermal and active power in Environmental Hubs. These Constraints state that only the BU is used to produce thermal energy, whereas RESs like WT, PV, and BU contribute to the creation of electrical energy. In addition to the BU, the FC, and HP also contribute to thermal energy production, although the HP is an active power consumer. HS and CAES are utilized for active power control and electrical energy storage within EH. TES is employed for thermal power control and thermal energy storage. The operational model of the RESs encompasses Wind Farms (WF), PV Farms (PVF), and BU Farms (BUF), as outlined in constraints (21)29, (22)30, and (23)-(24)17,18, respectively. As per constraint (21), the WT operates across four zones31,32,33,34,35. In the first and fourth zones, when the wind speed is either below the cut-in speed or above the cut-out speed, the wind turbine does not generate any power. The power generation rises linearly with wind speed in the second zone, which is defined by wind speeds between the cut-in speed and the nominal speed29. In the third zone, the wind speed surpasses the designated speed but stays below the threshold for automatic shutdown. Within this area, the power output of this source is consistently kept at its designated capacity in order to protect the mechanical components of the wind turbine. In accordance with constraint (22), the power output of photovoltaic systems (PVFs) is calculated by multiplying the number of PVs, their area, efficiency, and the solar radiation they receive30,36,37,38,39. Contrarily, Constraint (23), specifies that in order to calculate the active power output of BUFs40, the number and efficiency of BUs, the amount of methane in the BU gas, the low heating value of methane gas, and the gas produced by BUs are multiplied. Our research indicates that the BU is equipped with CHP technology, which allows it to produce both thermal and electrical energy. The quantity of thermal power produced by the BU is delineated in (24), which is a coefficient of the BU’s active power17. The operational model of HPs is expounded in (25) and (26). The HP is designed to convert electrical energy into thermal energy41. In essence, it acts as a consumer of active power and a producer of thermal power. Constraint (25) delineates the relationship between thermal power and active HP41. Constraint (26) takes into account the capacity limitation of power generation at the output of HPs. Constraints (27)-(31) present the operational model of HS42. Within HS, there are three components: FC, electrolyzer (EL), and Hydrogen Tank (HT). Hydrogen is produced by the electrolyzer and is then kept in the hydrogen tank. Hydrogen is taken out of the Hydrogen Tank (HT) by the FC and sent to the EH as thermal and electrical energy42. The fuel cell (FC) used in this study is assumed to be equipped with combined heat and power (CHP) technology, which enables it to produce thermal and electrical power concurrently. It is significant to notice that the FC is used in the discharge mode and the EL is engaged in the HS charging mode. As a result, in (27) and (28), respectively, the capacity limitations of the FC and EL are expressed. Because HS is unable to operate in both the charge and discharge modes at the same time, constraint (29) is used to prevent EL and FC from operating concurrently. Constraint (30) sets a maximum value for the amount of hydrogen energy that may be stored in HT42. According to this equation, the energy of hydrogen is equal to the sum of the original energy, the energy retained while charging, and the energy released. The CHP model for Fuel Cells (FC) is defined by Constraint (31) and states that the thermal power of an FC is proportionate to its active power. The limitations (32)–(35) characterize the CAES operating model43,44. A CAT, a generator, and a motor make up the CAES system. The motor works by transforming electrical energy into compressed air during the CAES charging phase. The pressurized air is then stored in the CAT, or compressed air tank. The generator runs during the compressed air energy storage (CAES) discharge phase, transforming compressed air into electrical energy43. The generator and motor’s capacity restrictions are represented by constraints (32) and (33). Constraint (34) prohibits the generator and motor from operating simultaneously. The maximum quantity of compressed air energy that may be stored in the CAT is expressed by restriction (35). According to this relation, the energy in CAT is equal to the sum of the initial energy and the energy stored in the CAES charging mode minus the energy discharged in the CAES discharge mode43. The operational model of TES is delineated in relations (36)-(39)3. Constraints (36) and (37) display the charge and discharge rate constraints45 of TES. Relation (38) stipulates the constraint that prevents simultaneous charge and discharge of TES, and (39) formulates the constraint on the energy stored in TES3.

Uncertainty modeling

In the proposed plan, parameters such as energy price, λE and λH, load (PD, QD, and HD), wind speed (v), solar radiation (IV), BU generated gas (GB), and network equipment availability (uEL, uHL, uES and uHS) are considered uncertain. It’s crucial to remember that this approach requires the computation of reliability indices such outage cost and EENS20. The computation of these indices provides a precise examination of various scenarios of load, power generation, and equipment availability in the network20. Consequently, stochastic planning, which leverages a combination of the RWM and SBM46, is employed for modeling the aforementioned uncertainties.

Scenario generation

In this part, the Robust Weighted Mean (RWM) method is used to produce a significant quantity of situations. This approach randomly gives values to unknown parameters in each individual case. The allocation of load, energy price, wind speed, sun radiation, and BU gas is based on their average value and variability. The Forced Outage Rate (FOR) of the network equipment determines its availability, denoted by u, in every circumstance. The normal Probability Density Function (PDF) is used to calculate the likelihood of chosen values for the load, energy price, and BU gas. The Weibull and Beta PDFs are used to determine the likelihood of certain wind speed and solar radiation values, respectively. Using the Bernoulli PDF, the chance of network equipment availability is also computed. Ultimately, the probability of each generated scenario (γ0) is determined as the product of the probabilities of the uncertainty parameters within that scenario.

Scenario reduction

First, a great deal of circumstances is created at random. To lessen the need for calculation, the scenario set should be reduced. The literature offers a variety of scenario reduction techniques46. Because SBM has great accuracy and no processing overhead, it is used in this study. In order to identify the most unlikely and dissimilar possibilities, this approach computes the distance between several scenarios. The following steps are employed to reduce the scenarios46:

-

Step 1 Consider ξs as the initial set of the scenarios. Additionally, consider DS to be the original empty collection of scenarios that remain after the scenario reduction procedure. Determine how far apart any two possibilities are using the formula below:

-

Step 2 Determine the least distance with other scenarios for each scenario Re:

where l holds the number of scenarios with the least distance from scenario s.

-

Step 3 Multiply the probability of each scenario prw with the least distance from other scenarios:

-

Step 4 Omit the dth scenario with the lowest value for the below criterion from the initial scenarios set ξs:

-

Step 5 Repeat Steps 2 to 4 until reaching the desired number of scenarios.

Similar situations and scenarios with low probability will be excluded by the aforementioned scenario reduction process. As a result, the remaining scenario set is sufficiently varied to represent the problem’s maximum uncertainty spectrum. All of the above outcomes would lead to a framework that is deterministic-equivalent to the stochastic problem. The optimal solutions of different scenarios are combined via an aggregation process to construct the final optimal solution as (1). γw is:

This equation yields a single optimum solution for the stochastic issue rather than a collection of solutions. Through the use of this aggregating method, it becomes feasible to not only analyze each individual scenario, but also maintain the original structure of the stochastic issue. Figure 2 displays the flowchart of uncertainty modeling, which is derived from the integration of RWM and SBM.

The proposed scheme is in the form of a mathematical model47,48,49,50,51. This mathematical model includes the optimization formulation52,53,54. It includes an objective function that has the task of minimizing or maximizing one or more objective functions55,56,57,58. This problem includes various constraints that are equal and unequal59,60,61,62,63. To apply the optimization problem to the network, an intelligent platform is needed. This platform includes telecommunication devices and intelligent algorithms64,65,66,67.

Numerical simulation

Data

Figure 3 illustrates how the EMS covered in this section is applied to both the IEEE 33-bus electrical network68 and the 14-node Madumvej heat network69. The electrical network runs on a base power of 1 MVA and a voltage of 12.66 kV. As the reference bus, Bus 1 maintains both a voltage angle of zero and a voltage amplitude (Vref) of one per unit (p.u.). Voltage amplitude is allowed to vary from 0.9 to 1.1 per unit (p.u.)70,71,72,73,74,75,76. The requirements for the distribution lines and distribution post are outlined in reference68. The maximum active and reactive load for several busses was documented in the work in reference68. The load factor curve multiplied by the maximum load yields the load at different time intervals77,78,79,80,81. The expected daily curve of the load factor for the electrical network is illustrated in Fig. 417,18. The price of electrical energy during off-peak hours, specifically between 1:00 and 7:00, is 17.6 $/MWh. The energy price during peak hours, specifically between 17:00 and 22:00, is 33 $/MWh. For other hours, referred to as mid-load, the energy price is 26.4 $/MWh17,82,83,84. The total emissions factor, accounting for CO2, SO2, and NOx emissions when supplying electrical energy from the upstream network, is 918.2 ton/MW19. In the heat network, the base power and temperature are 1 MW and 100 °C, respectively. The slack node, Node 1, has a temperature (Tref) of 1 p.u. The acceptable temperature ranges for various nodes spans from 0.9 p.u. to 1.1 p.u. Details regarding the pipeline and heat post are available in69. Peak load data for various nodes can also be found in Ref.69, and Fig. 4 shows the heat load factor’s projected daily curve16. For both peak (5:00–15:00) and off-peak (1:00–4:00 and 16:00–24:00) hours, the price of thermal energy is fixed at 22 $/MWh17. The heat post’s total emissions factors for CO2, SO2, and NOx are 714.6 ton/MW. This paper assumes that the N – 1 incident occurs over the course of one day’s operation, and the Forced Outage Rate (FOR) for lines and posts across various networks is 1%20.

As depicted in Fig. 3, the system under examination utilizes six hubs. The locations of the EHs are detailed in this figure, and the quantity of sources, storage units, and installed HPs in each EH align with the data in Table 2. This table indicates that hubs 1 and 2 deliver thermal energy via BUF, while hubs 4 and 5 provide thermal energy in accordance with the HPs present in these hubs. Hubs 1, 4, and 5 possess CAES type electrical storage, whereas the remaining hubs feature HS type electrical storage. Table 3 provides a detailed overview of the specs for each source, storage unit, and HP. The load of each hub is equivalent to the load of the hub’s position within the network. Figure 4 displays the anticipated graph of wind speed rate, BU gas, and sun radiation17,29,30. An uncertainty of 10% is considered as the standard deviation for energy price, load, wind speed, sun radiation, and BU gas.

Results and discussion

The simulation in this part is conducted using the GAMS software environment. The suggested system is solved using the IPOPT algorithm85. Subsequently, the quantitative findings are presented in the next section.

Analysis of the objective function

This section aims to determine the optimal VOLL and VOEP, as well as to scrutinize the objective functions, as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. Figure 5 plots the environmental indices, namely EEM and EEC, and the economic index, EOC, based on VOEP. Based on Fig. 5(a), an increase in the VOEP up to 0.09 $/ton results in a decrease in emissions, as measured by EEM, from 97,000 tons to 13,856 tons. For VOEP values greater than or equal to 0.09 $/ton, the EEM value remains constant. Figure 5(b) outlines the status of the emissions cost, EEC, and network operation cost, EOC, in relation to VOEP. This figure reveals that EEC escalates with an increase in VOEP, as the impact of changes in VOEP has a more significant effect on EEC than changes in EEM. Similarly, EOC rises with an increase in VOEP up to 0.09 $/ton, but for VOEP values greater than or equal to 0.09 $/ton, EOC saturates. In order to lower the EEM, EHs must significantly reduce the amount of electricity that is received from the upstream network by injecting it into the network during different working hours. It’s crucial to remember that at certain hours, RESs could not be able to inject high power. During these periods, HPs and storage units are required to inject substantial power into the network. This issue is further explored in Sect. 4.2.B. For high energy discharge, storage units must obtain high energy consumption in discharge mode. Also, HPs require electrical energy to generate thermal energy. In such a scenario, it’s expected that the energy losses of the aforementioned elements will escalate, leading to an increase in EOC. Consequently, as VOEP rises, EEM diminishes, and the EOC augments. According to Fig. 5, the optimal price of VOEP is 0.09 $/ton. This is attributed to the fact that at this VOEP value, the EEM reaches its minimum value and EOC reaches saturation. Additionally, EEC at this juncture has the lowest value compared to when VOEP exceeds 0.09 $/ton.

The state of the economic index, EOC, and the reliability indices, EENS and ERC, with respect to VOLL is shown in Fig. 6. According to Fig. 6(b), EENS decreases as VOLL increases up to 80 $/MWh. Nonetheless, the EENS value stays constant and achieves its minimal value at VOLL values larger than or equal to 80 $/MWh. Moreover, Fig. 6(b) shows that a rise in VOLL always results in a rise in ERC. As the impact of VOLL changes on ERC is greater than the impact of EENS changes. According to Fig. 6(b), an increase in VOLL up to 80 $/MWh corresponds to a rise in EOC. However, for VOLL values greater than or equal to 80 $/MWh, the EOC reaches a saturation point and remains constant. To minimize EENS, it’s necessary for sources, storage units, and HPs to inject substantial power into the network at various hours. This situation is accompanied by an increase in the energy losses of storage units and HPs. Under these circumstances, it’s expected that energy losses in both electrical and thermal networks will escalate. This could be attributed to the potential for a significant increase in power from the hub to the reference bus. These factors contribute to an increase in EOC. Consequently, as VOLL increases, EENS decreases and EOC increases. Another point to note is that the optimal price for VOLL is 80 $/MWh. This value corresponds to the minimum value of EENS, and it’s at this point that the EOC reaches saturation. Additionally, ERC at this point is lower compared to when VOLL exceeds 80 $/MWh.

In Figs. 5 and 6, increasing VOLL and VOEP increases the importance of minimizing the reliability and environmental objective functions in Eq. (1). Therefore, this makes the performance of energy hubs proportional to the minimization of the expressed functions. In other words, with increasing VOLL (VOEP), to reduce the reliability (environmental) cost, it is necessary for the hubs to inject higher energy into the energy networks than in the case of low VOLL (VOEP). In this case, EENS (EEM) is reduced, which results in improving the reliability (environmental) status of the energy networks.

Table 4 presents the economic, environmental, and reliability status of the electrical and thermal networks for the optimal values of VOLL and VOEP. This table reports on the following case studies:

-

Case I A load flow study.

-

Case II A proposed scheme considering an EH that includes only WF, PVF, and BUF.

-

Case III An EH that is a hybrid system of WF, PVF, BUF, and HP.

-

Case IV A proposed scheme that includes a renewable EH with HP, CAES, HS, and TES.

Table 4 shows that Case I has the greatest values for the dependability, environmental, and economic indices. our is mostly because electricity is obtained from the upstream network in our example study. Since there are no local sources in the energy networks, there is no control over power, which also implies that EEM, EENS, and EOC are not under control. Case II demonstrates the impact of incorporating RESs into the EHs. The presence of these RESs significantly improves various indices. Specifically, in this case study, EEM, EENS, EOC, ERC, and EEC decreased by approximately 57.6% (calculated as (49722–21078)/49722), 75.9%, 24.1%, 75.9%, and 57.6% respectively, compared to case I. Under these conditions, the objective function, represented by Cost, decreases by approximately 55.6% compared to Case (I) The addition of HP to Case II, forming Case III, results in a more favorable status for all the mentioned indices compared to Cases I and (II) Specifically, EEM, EENS, EOC, ERC, EEC, and Cost in Case III decrease by approximately 62.5%, 79%, 31.7%, 79%, 62.5%, and 60% respectively, compared to Case I. Case IV concludes by reporting on the ideal condition of economic, environmental, and reliability indicators for electrical and thermal networks. This example is based on models (1) through (39). According to Table 4, the proposed scheme compared to case I has managed to reduce EEM, EENS, EOC, ERC, EEC, and Cost by approximately 72.1%, 85.6%, 44.1%, 85.6%, 72.1%, and 69.8%, respectively.

Performance evaluation of renewable EHs based on storage and HP

The expected daily curves of active and thermal power for sources, storage units, HPs, and EHs at optimal VOLL and VOEP levels are shown in Figs. 7 and 8. The daily curves of wind, solar, and biomass energy sources (RESs) are shown in Fig. 7, which shows a numerical reflection of the daily curves of wind speed rate, sun radiation rate, and BU gas rate shown in Fig. 4. This is attributed to the fact that, according to relations (21)-(23), the active power and production of RESs are influenced by the wind speed rate, solar radiation rate, or BU gas rate. Based on Fig. 7, WF, BUF, and PVF, and PVF exhibit the highest active power generation, with respective outputs of 1.8 MW, 2.4 MW, and 1.08 MW. In terms of the performance of HS, it’s observed from Fig. 7 that they are inactive during off-peak hours, specifically from 1:00 to 7:00. This corresponds to periods of lower electricity prices. During mid-load hours, 8:00–16:00, they are in charge mode, and active power is received by ELs for HS from hubs. This is because during these hours, RESs have a high active power production and full injection of it into the electrical distribution network could lead to excess voltage. Therefore, to prevent severe overvoltage conditions, HSs receive power from RESs during these hours. During these hours, they can receive all their energy consumption from RESs, so the cost of their energy consumption that must be paid to the upstream network is zero. HSs operate in charge mode between 17:00 and 22:00, while FCs provide active power to the network between 23:00 and 24:00. HSs may reduce their EOC during these hours since electricity is costlier. CAES operates similarly to HS, with the exception of adding extra active power to the network during peak hours. This is because, in CAES, the efficiency of the motor and generator is close to each other based on Table 3, but this is not true for EL and FC. Also, the efficiency of FC is much less than the generator. Therefore, energy losses in HS are higher than CAES, so its active power in discharge mode is lower than CAES. As another point, HSs and CAESs were off during off-peak hours, because during these hours, according to Fig. 7, the level of active power produced by RESs is low. Therefore, it is expected that if the storage units consume energy during these hours, a percentage of the energy consumed by the mentioned storage units will be supplied by the electrical network. Under these circumstances, EOC is not minimized. In addition, the performance of the mentioned storage units has caused the EHs to always act as producers of electrical energy based on Fig. 7. Under these circumstances, EHs are able to provide active power to the electrical grid throughout all of its operational hours. This conduct is consistent with minimizing EEM and EENS. When it comes to HP performance, they are powered by EHs and are operational from 1:00 to 7:00 and 17:00 to 24:00. During the hours of 1:00–7:00, the power produced by WFs in hub 4 is around 1 MW (WT capacity ⋅ number of WTs in this hub), but according to Fig. 4, HPs have less than 1 MW of active power during these hours. Therefore, the energy consumed by HPs in hub 4 is supplied by EHs or RESs. In Hub 5, the only RES is solar, which, according to Fig. 7, has a low level of energy production during low-load hours. As a result, the HPs in Hub 5 rely on the electrical grid for active power. Between 17:00 and 24:00, HSs, CAESs, and WFs in Hubs 4 and 5 generate a significant quantity of active power. As a result, during these hours, HPs rely on EHs for active power. However, note that the total active power of EHs is always positive, indicating that all EHs can act as electric energy producers during operation hours.

The time curve for the thermal power of BUFs, HPs, TESs, and EHs is shown in Fig. 8. The daily thermal power curve of BUFs and the active power curve are similar, differing just slightly in numbers. This is due to the validity of Eq. (24), which states that BU’s thermal power is a function of its active power. When the TESs are in discharge mode, the thermal peak hour is from 5:00 to 15:00. These hours correspond to periods of high thermal energy prices. Therefore, the discharge operation of TESs during these hours leads to the minimization of EOC. At other times, TESs are in charge mode. However, during these hours, the level of BUFs’ power production is lower compared to peak load hours. Specifically, from 1:00–6:00 and 20:00–24:00, the power produced by BUFs is less than the load consumed by EHs. Therefore, during these hours, to prevent TESs from receiving thermal power from the network, HPs are turned on and produce thermal energy for the hubs. In line with this, and based on Fig. 8, EHs can always act as energy producers. Hence, they constantly inject thermal power into the thermal network, and following this, EOC, EEM, and EENS in the thermal network are minimized.

Analysis of the operational status of electrical and thermal networks

The following are a few instances of operational indices: Peak Load Carrying Capacity (PLCC) for the ideal values of VOLL and VOEP for study cases I through IV; Maximum Voltage Drop (MVD) and Temperature Drop (MTD); Maximum Over Voltage (MOV) and Over Temperature (MOT); Expected Energy Loss (EEL) in the electrical (E-EEL) and thermal (T-EEL) networks; and Maximum Over Voltage (MOV) and Maximum Temperature (MOT). PLCC represents the maximum peak load proportional to the daily load curve load factor in Fig. 4 that can be fed by the network. According to Table 5, the most significant energy losses, voltage drops, and temperature decreases are observed in the load distribution studies of energy networks (Case I), This case also exhibits the lowest PLCC, overvoltage, and temperature. In contrast, Case II, which includes RESs at the hubs, shows improvement in all indices, with the exception of overvoltage and temperature. As a result, compared to Case I, the values of E-EEL, T-EEL, EEL, MVD, and MTD drop by around 28.5%, 30.7%, 29.5%, 41.3%, and 40.7%, respectively. On the other hand, in contrast to Case I, the PLCC in the thermal and electrical networks indicates an increase of around 64.6% and 63.4%, respectively. In Case II, MOV and MOT rise from zero in Case I to 0.031 p.u. and 0.021 p.u. respectively. With the addition of HP to Case II (Case III), a more desirable situation for operational indices is achieved compared to Cases I and II. In such a way that E-EEL, T-EEL, EEL, MVD, and MTD decrease by approximately 31.7%, 34.2%, 32.9%, 42.4%, and 45.3% respectively compared to Case (I) However, E-PLCC and T-PLCC increase by about 63.4% and 71.5% respectively compared to load distribution studies. Additionally, the introduction of HP has led to a reduction in MOV and MOT by approximately 16.1% and 14.3% respectively compared to Case (II) Finally, in Case IV, which aligns with model (1)-(39) and features hubs equipped with storage, HP, and RES, a more optimal operational situation is observed compared to the other cases studied. In this case, compared to Case I, E-EEL, T-EEL, EEL, MVD, and MTD decrease by approximately 41%, 42.9%, 41.9%, 48.9%, and 47.7% respectively. PLCC for both the electrical and thermal networks increases by about 82.5% and 89.5% respectively compared to Case I. MOV and MOT also decrease by 41.9% and 28.6% respectively compared to Case II.

The proposed design aimed to minimize the operating, pollution, and reliability costs of the electrical and thermal networks. To achieve these conditions, energy hubs should be able to generate energy at most of the time, and they should be able to inject active and thermal power into the energy networks at most of the time. In the hubs, renewable sources did not have the ability to control their power. Therefore, energy storage devices and heat pumps should control their power so that the hubs can play the role of energy producers. According to Figs. 7 and 8, the storage devices are in discharge mode during hours when the renewable sources generate low power. During times when the renewable sources generate high power, the storage devices are in charge mode to prevent overvoltage and temperature. The heat pumps were also turn-on during hours when the BUs generated low thermal power. This function of resources and storage devices has caused hubs to always be in the role of energy producers, so that they have been able to improve the economic, environmental, and technical objective functions compared to Case I (load distribution studies).

Conclusions

Based on environmental indices and dependability, this article discussed the cost-effective operation of thermal and electrical networks with renewable energy hubs, such as hydrogen, thermal and compressed air storage, wind turbines, solar and bio-waste units, and heat pumps. The suggested solution sought to lower emissions, improve reliability, and decrease overall estimated operating costs. It was restricted by the operational model of the designated hubs, reliability limitations, and the optimum power distribution model of the networks under consideration. Uncertainties like load, energy pricing, solar radiation, wind speed, gas generated from waste, and the availability of energy network equipment were all taken into consideration in the design. Stochastic optimization based on scenarios was used in this work to accurately calculate the dependability index while accounting for a variety of uncertainties. The numerical findings showed that it is feasible to achieve the least projected amount of unfed energy and emissions by selecting an ideal penalty price (high) for network interruption in the case of N − 1 and emissions. However, these conditions lead to an increase in the operational cost of energy networks when compared to a scenario with a zero penalty price. Nevertheless, the proposed plan, which involves optimal energy management of storage and heat pumps in conjunction with renewable sources within hubs, has succeeded in improving the reliability and environmental status by approximately 85.6% and 72.1% respectively, when compared to the network load distribution studies. Furthermore, the economic status of the energy networks has seen an improvement of approximately 44% when compared to the load distribution case. This approach may lead to improvements in a number of operational indicators, such as effective power management for heat pumps, compressed air, hydrogen, and thermal storage in the renewable energy hub. They include energy losses, voltage and temperature profiles, and maximum feedable load, all of which have improved by 28–90% when compared to previous load distribution studies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article, Sect. 4.1. Also, the datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

20 August 2025

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16680-4

Abbreviations

- Cost :

-

Expected cost of operation, reliability, and emissions ($)

- EEM :

-

Expected total emissions of energy networks ($)

- EEC :

-

Expected total cost of emissions of energy networks ($)

- EENS :

-

Expected energy not supplied in energy networks (MWh)

- EOC :

-

Expected operating cost of energy networks ($)

- ERC :

-

Expected reliability cost of energy networks ($)

- H B , H HP , H F :

-

Thermal power of bio-waste unit (BU), heat pump (HP), and fuel cell (FC) in MW

- H CH , H DIS :

-

Thermal power of thermal energy storage (TES) in charge and discharge mode (MW)

- P B , P V , P W :

-

Active power of BU, photovoltaic (PV), and wind turbine (WT) in MW

- P E , P F :

-

Active power of electrolyzer (EL) and FC in hydrogen storage (HS) in MW

- P EH , H EH :

-

Active and thermal power of energy hub (EH) in MW

- P HP :

-

Active power of HP in MW

- P L , Q L , H L :

-

Active (MW) and reactive (MVAr) power passing through the electric distribution line, and thermal power (MW) passing through the heat pipe

- P M , P G :

-

Active power of motor and generator in compressed air energy storage (CAES) in MW

- P N , H N :

-

Not supplied active load and Not supplied thermal load (MW)

- P S , Q S , H S :

-

Active (MW) and reactive (MVAr) power passing through the electric distribution post, and thermal power (MW) passing through the heat post

- T :

-

Temperature (p.u.)

- V, φ :

-

Voltage range (p.u.) and voltage angle (radian)

- A E :

-

Intersection matrix of bus and electric distribution line

- A H :

-

Intersection matrix of node and heat pipe

- B L , G L :

-

Susceptance and conductance of electric distribution line (p.u.)

- C E :

-

Intersection matrix of EH and electric bus

- C H :

-

Intersection matrix of EH and heat node

- C L :

-

Thermal constant of the heat pipe (p.u.)

- \(\underline {E}_{CAT} ,\overline{E}_{CAT} ,\hat{E}_{CAT}\) :

-

Minimum and maximum energy stored in compressed air tank (CAT) and its initial energy (MWh)

- \(\underline {E}_{HT} ,\overline{E}_{HT} ,\hat{E}_{HT}\) :

-

Minimum and maximum energy stored in hydrogen tank (HT) and its initial energy (MWh)

- \(\underline {E}_{TES} ,\overline{E}_{TES} ,\hat{E}_{TES}\) :

-

Minimum and maximum energy stored in TES and its initial energy (MWh)

- \(\overline{H}_{CH} ,\overline{H}_{DIS}\) :

-

Charge/discharge rate in TES (MW)

- \(\overline{H}_{L} ,\overline{H}_{S}\) :

-

Maximum thermal power passing through the heat pipe and heat post (MW)

- \(\overline{H}_{HP}\) :

-

Maximum thermal power produced by HP (MW)

- n B, η B , G B :

-

Number of BUs, efficiency, and gas (m3) produced by BU

- n V , A V, η V , I V :

-

Number of PVs, area (m2), efficiency, and solar radiation (kW/m2) of PV

- n CA , n HS , n T , n HP :

-

Number of CAESs, HS, TES, and HP

- n W :

-

Number of WTs

- \(\overline{P}\) :

-

Capacity of WT (MW)

- P D , Q D , H D :

-

Active (MW), reactive (MVAr), and thermal (MW) load

- \(\overline{P}_{E} ,\overline{P}_{F}\) :

-

EL and FC capacity in HS (MW)

- \(\overline{P}_{M} ,\overline{P}_{G}\) :

-

Motor and generator capacity in CAES (MW)

- \(\overline{S}_{L} ,\overline{S}_{S}\) :

-

Maximum apparent power passing through electric distribution line and post (MVA)

- T min , T max :

-

Minimum and maximum permissible temperature (p.u.)

- u EL , u ES :

-

Accessibility of electric distribution line and post

- u HL , u HS :

-

Accessibility of heat pipe and post

- v, v r , v c-in , v c-out :

-

Wind speed, nominal value, cut-in, and cut-out (m/s)

- V min , V max :

-

Minimum and maximum permissible voltage range (p.u.)

- VOEP :

-

Pollution penalty price ($/ton)

- VOLL :

-

Value of lost load ($/MWh)

- V ref , T ref :

-

Voltage and temperature range in slack bus (p.u.)

- γ :

-

Probability of scenario occurrence

- η CH, η DIS :

-

Charge and discharge efficiency in TES

- η E, η F :

-

EL and FC efficiency in HS

- η H :

-

Thermal efficiency in combined heat and power (CHP)

- η HP :

-

HP efficiency

- η M, η G :

-

Motor and generator efficiency in CAES

- λ E, λ H :

-

Electric and thermal energy price ($/MWh)

- ρ CH4 , LHV CH4 :

-

Methane percentage in BU gas and low heat value for methane gas (kW/m3)

- ρ E, ρ H :

-

Pollution coefficient for supplying electric and thermal energy from centralized energy production units (ton/MW)

- b, n :

-

Bus in the electric network, a node in the heat network

- i :

-

EH

- j :

-

Auxiliary index corresponding to bus or node

- t, w :

-

Operating hour, scenario

References

Babinec, S. et al. Techno-economic analysis of renewable energy generation at the South Pole. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 193, 114274 (2024).

Awasthi, M. K. et al. Techno-economics and life-cycle assessment of biological and thermochemical treatment of bio-waste. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 144, 110837 (2021).

Zhang, X., Yu, X., Ye, X. & Pirouzi, S. Economic energy management of networked flexi-renewable energy hubs according to uncertainty modeling by the unscented transformation method. Energy 278, 128054 (2023).

Nabat, M. H., Habibzadeh, M., Alsagri, A. S. & Arabkoohsar, A. An investigation and multi-criteria optimization of an innovative compressed air energy storage. J. Energy Storage 76, 109645 (2024).

Drawer, C., Lange, J. & Kaltschmitt, M. Metal hydrides for hydrogen storage—identification and evaluation of stationary and transportation applications. J. Energy Storage 77, 109988 (2024).

Kumar, R. P. & Karthikeyan, G. A multi-objective optimization solution for distributed generation energy management in microgrids with hybrid energy sources and battery storage system. J. Energy Storage 75, 109702 (2024).

Dini, A., Pirouzi, S., Norouzi, M. & Lehtonen, M. Grid-connected energy hubs in the coordinated multi-energy management based on day-ahead market framework. Energy 188, 116055 (2019).

Jamali, A. et al. Self-scheduling approach to coordinating wind power producers with energy storage and demand response. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 11 (3), 1210–1219 (2019).

Nasir, M. Optimal operation of energy hubs including parking lots for hydrogen vehicles and responsive demands. J. Energy Storage 50, 104630 (2022).

Nasir, M. Operation of energy hubs with storage systems, solar, wind and biomass units connected to demand response aggregators. Sustain. Cities Soc. 83, 103974 (2022).

Li, R. & Saeid-Nahaei, S. Optimal operation of energy hubs integrated with electric vehicles, load management, combined heat and power unit and renewable energy sources. J. Energy Storage 48, 103822 (2022).

Aslani, M., Mashayekhi, M., Hashemi-Dezaki, H. & Ketabi, A. Robust optimal operation of energy hub incorporating integrated thermal and electrical demand response programs under various electric vehicle charging modes. Appl. Energy 321, 119344 (2022).

George-Williams, H., Wade, N. & Carpenter, R. N. A probabilistic framework for the techno-economic assessment of smart energy hubs for electric vehicle charging. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 162, 112386 (2022).

Rezaee Jordehi, A. Two-stage stochastic programming for risk-aware scheduling of energy hubs participating in day-ahead and real-time electricity markets. Sustain. Cities Soc. 81, 103823 (2022).

Talebjedi, B., Laukkanen, T., Holmberg, H. & Syri, S. Advanced design and operation of Energy Hub for forest industry using reliability assessment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 230, 120751 (2023).

Iranpour-Mobarakeh, A., Sadeghi, R., Saghafi-Esfahani, H. & Delshad, M. Optimal planning and operation of energy hub by considering demand response algorithms and uncertainties based on problem-solving approach in discrete and continuous space. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 214, 108859 (2023).

Akbari, E., Mousavi-Shabestari, S. F., Pirouzi, S. & Jadidoleslam, M. Network flexibility regulation by renewable energy hubs using flexibility pricing-based energy management. Renew. Energy 206, 295–308 (2023).

Qu, Z., Xu, C., Yang, F., Ling, F. & Pirouzi, S. Market clearing price-based energy management of grid-connected renewable energy hubs including flexible sources according to thermal, hydrogen, and compressed air storage systems. J. Energy Storage 69, 107981 (2023).

Roustaee, M. & Kazemi, A. Multi-objective stochastic operation of multi-microgrids constrained to system reliability and clean energy based on energy management system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 194, 106970 (2021).

Aghaei, J., Amjady, N., Baharvandi, A. & Akbari, M. A. Generation and transmission expansion planning: MILP-based probabilistic model. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 29 (4), 1592–1601 (2014).

Jiang, W. et al. Optimal economic scheduling of microgrids considering renewable energy sources based on energy hub model using demand response and improved water wave optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 55, 105311 (2022).

Dehghani, M. et al. Blockchain-based securing of data exchange in a power transmission system considering congestion management and social welfare. Sustainability 13, 90 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Optimal modeling of combined cooling, heating, and power systems using developed African vulture optimization: a case study in watersport complex. Energy Sources A Recov. Utiliz. Environ. Eff. 44 (2), 4296–4317 (2022).

Yuan, Z. et al. Probabilistic decomposition-based security constrained transmission expansion planning incorporating distributed series reactor. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 14 (17), 3478–3487 (2020).

Yu, D. & Ghadimi, N. Reliability constraint stochastic UC by considering the correlation of random variables with Copula theory. IET Renew. Power Gener. 13 (14), 2587–2593 (2019).

Eslami, M. et al. A new formulation to reduce the number of variables and constraints to expedite SCUC in bulky power systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. A Phys. Sci. 89, 311–321 (2019).

Nejad, H. C. et al. Reliability based optimal allocation of distributed generations in transmission systems under demand response program. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 176, 105952 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Optimal operation of CCHP and renewable generation-based energy hub considering environmental perspective: an epsilon constraint and fuzzy methods. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 20, 100274 (2019).

Khalafian, F. et al. Capabilities of compressed air energy storage in the economic design of renewable off-grid system to supply electricity and heat costumers and smart charging-based electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 78, 109888 (2024).

Maleki, P. A. & Askarzadeh, A. Optimal sizing of a PV/wind/diesel system with battery storage for electrification to an off-grid remote region: a case study of Rafsanjan, Iran. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 7, 147–153 (2014).

Leng, H. et al. A new wind power prediction method based on ridgelet transforms, hybrid feature selection and closed-loop forecasting. Adv. Eng. Inform. 36, 20–30 (2018).

Abedinia, O. et al. A new combinatory approach for wind power forecasting. IEEE Syst. J. 14 (3), 4614–4625 (2020).

Mir, M. et al. Application of hybrid forecast engine based intelligent algorithm and feature selection for wind signal prediction. Evol. Syst. 11 (4), 559–573 (2020).

Bo, G. et al. Optimum structure of a combined wind/photovoltaic/fuel cell-based on amended Dragon fly optimization algorithm: a case study. Energy Source A Recover. Utiliz. Environ. Eff. 44 (3), 7109–7131 (2022).

Zhu, L. et al. Multi-criteria evaluation and optimization of a novel thermodynamic cycle based on a wind farm, Kalina cycle and storage system: an effort to improve efficiency and sustainability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 96, 104718 (2023).

Ghadimi, N. et al. An innovative technique for optimization and sensitivity analysis of a PV/DG/BESS based on converged Henry gas solubility optimizer: a case study. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 17 (21), 4735–4749 (2023).

Mehrpooya, M. et al. Numerical investigation of a new combined energy system includes parabolic dish solar collector, Stirling engine and thermoelectric device. Int. J. Energy Res. 45 (11), 16436–16455 (2021).

Meng, Q. et al. A single-phase transformer-less grid-tied inverter based on switched capacitor for PV application. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 31, 257–270 (2020).

Abedinia, O. et al. Optimal offering and bidding strategies of renewable energy based large consumer using a novel hybrid robust-stochastic approach. J. Clean. Prod. 215, 878–889 (2019).

Chang, L., Wu, Z. & Ghadimi, N. A new biomass-based hybrid energy system integrated with a flue gas condensation process and energy storage option: an effort to mitigate environmental hazards. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 177, 959–975 (2023).

Chua, K. J., Chou, S. K. & Yang, W. M. Advances in heat pump systems: a review. Appl. Energy 87, 3611–3624 (2010).

Zhang, Y., Campana, P. E., Lundblad, A. & Yan, J. Comparative study of hydrogen storage and battery storage in grid connected photovoltaic system: Storage sizing and rule-based operation. Appl. Energy 201, 397–411 (2017).

Olabi, A. G. et al. Compressed air energy storage systems: components and operating parameters—A review. J. Energy Storage 34, 102000 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. Optimal bidding and offering strategies of compressed air energy storage: a hybrid robust-stochastic approach. Renew. Energy 143, 1–8 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. An IGDT-based risk-involved optimal bidding strategy for hydrogen storage-based intelligent parking lot of electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 27, 101057 (2020).

Lei, W., Shahidehpour, M. & Tao, L. Stochastic security-constrained unit commitment. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 22, 800e11 (2007).

Mohammadi, M. et al. Small-scale building load forecast based on hybrid forecast engine. Neural Process. Lett. 48, 329–351 (2018).

Khodaei, H. et al. Fuzzy-based heat and power hub models for cost-emission operation of an industrial consumer using compromise programming. Appl. Therm. Eng. 137, 395–405 (2018).

Hamian, M. et al. A framework to expedite joint energy-reserve payment cost minimization using a custom-designed method based on mixed integer genetic algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 72, 203–212 (2018).

Akbary, P. et al. Extracting appropriate nodal marginal prices for all types of committed reserve. Comput. Econ. 53, 1–26 (2019).

Saeedi, M. et al. Robust optimization based optimal chiller loading under cooling demand uncertainty. Appl. Therm. Eng. 148, 1081–1091 (2019).

Karamnejadi Azar, K. et al. Developed design of battle royale optimizer for the optimum identification of solid oxide fuel cell. Sustainability 14, 9882 (2022).

Mahdinia, S. et al. Optimization of PEMFC model parameters using meta-heuristics. Sustainability 13, 12771 (2021).

Rezaie, M. et al. Model parameters estimation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell by a modified golden Jackal optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 53, 102657 (2022).

Guo, H. et al. Parameter extraction of the SOFC mathematical model based on fractional order version of dragonfly algorithm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47 (57), 24059–24068 (2022).

Ye, H. et al. High step-up interleaved dc/dc converter with high efficiency. Energy Source A Recover. Utiliz. Environ. Eff. 1, 1–20 (2020).

Duan, F. et al. Model parameters identification of the PEMFCs using an improved design of crow search algorithm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47 (79), 33839–33849 (2022).

Zhang, J., Khayatnezhad, M. & Ghadimi, N. Optimal model evaluation of the proton-exchange membrane fuel cells based on deep learning and modified African vulture optimization algorithm. Energy Source A Recover. Utiliz. Environ. Eff. 44 (1), 287–305 (2022).

Han, E. & Ghadimi, N. Model identification of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells based on a hybrid convolutional neural network and extreme learning machine optimized by improved honey badger algorithm. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 52, 102005 (2022).

Yuan, K. et al. Optimal parameters estimation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell stacks using a combined owl search algorithm. Energy Source A Recover. Utiliz. Environ. Eff. 45 (4), 11712–11732 (2023).

Guo, X. & Ghadimi, N. Optimal design of the proton-exchange membrane fuel cell connected to the network utilizing an improved version of the metaheuristic algorithm. Sustainability 15, 13877 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Evaluating the efficiency of CCHP systems in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region: an optimal strategy based on improved mother optimization algorithm. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 54, 104005 (2024).

Ghiasi, M. et al. A comprehensive review of cyber-attacks and defense mechanisms for improving security in smart grid energy systems: past, present and future. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 215, 108975 (2023).

Gong, Z., Li, L. & Ghadimi, N. SOFC stack modeling: a hybrid RBF-ANN and flexible Al-Biruni Earth radius optimization approach. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 19, 1337–1350 (2024).

Han, M. et al. Timely detection of skin cancer: an AI-based approach on the basis of the integration of echo state network and adapted seasons optimization algorithm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 94, 106324 (2024).

Liu, H. & Ghadimi, N. Hybrid convolutional neural network and flexible dwarf mongoose optimization algorithm for strong kidney stone diagnosis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 91, 106024 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. A deep learning outline aimed at prompt skin cancer detection utilizing gated recurrent unit networks and improved orca predation algorithm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 90, 105858 (2024).

Babu, P. R. et al. A novel approach for solving distribution networks. In Proceedings of the Annual IEEE India Conference, Ahmedabad, India 1–5 (2009).

Gabrielaitiene, I., Bøhm, B. & Sundén, B. Dynamic temperature simulation in district heating systems in Denmark regarding pronounced transient behaviour. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 17, 79–87 (2011).

Norouzi, M. et al. IEEE,. Enhancing distribution network indices using electric spring under renewable generation permission. In 2019 International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST) 1–6 (2019).

Zadehbagheri, M. et al. The impact of sustainable energy technologies and demand response programs on the hub’s planning by the practical consideration of tidal turbines as a novel option. Energy Rep. 9, 5473–5490 (2023).

Bagherzadeh, L. et al. Coordinated flexible energy and self-healing management according to the multi‐agent system‐based restoration scheme in active distribution network. IET Renew. Power Gener. 15 (8), 1765–1777 (2021).

Navesi, R. B., Naghibi, A. F., Zafarani, H., Tahami, H. & Pirouzi, S. Reliable operation of reconfigurable smart distribution network with real-time pricing-based demand response. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 241, 111341 (2025).

Norouzi, M. et al. Risk-averse and flexi-intelligent scheduling of microgrids based on hybrid Boltzmann machines and cascade neural network forecasting. Appl. Energy 348, 121573 (2023).

Yao, M. et al. Stochastic economic operation of coupling unit of flexi-renewable virtual power plant and electric spring in the smart distribution network. IEEE Access 1, 1 (2023).

Pirouzi, S., Zadehbagheri, M. & Behzadpoor, S. Optimal placement of distributed generation and distributed automation in the distribution grid based on operation, reliability, and economic objective of distribution system operator. Electr. Eng. 1, 1–14 (2024).

Akbari, E. et al. Multi-objective economic operation of smart distribution network with renewable-flexible virtual power plants considering voltage security index. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 19136 (2024).

Zadehbagheri, M. et al. Resiliency-constrained placement and sizing of virtual power plants in the distribution network considering extreme weather events. Electr. Eng. 1, 1–17 (2024).

Oboudi, M. H. et al. Reliability-constrained transmission expansion planning based on simultaneous forecasting method of loads and renewable generations. Electr. Eng. 1, 1–21 (2024).

Naghibi, A. F. et al. Stochastic economic sizing and placement of renewable integrated energy system with combined hydrogen and power technology in the active distribution network. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 28354 (2024).

Pirouzi, S., Aghaei, J., Shafie-Khah, M., Osório, G. J. & Catalão, J. P. S. Evaluating the security of electrical energy distribution networks in the presence of electric vehicles. In 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech 1–6 (IEEE, 2017).