Abstract

Concrete compressive strength is a critical parameter in construction and structural engineering. Destructive experimental methods that offer a reliable approach to obtaining this property involve time-consuming procedures. Recent advancements in artificial neural networks (ANNs) have shown promise in simplifying this task by estimating it with high accuracy. Nevertheless, conventional ANNs often require deep networks to achieve acceptable results in cases with large datasets and where generalization is required for a variety of mixtures. This leads to increased training durations and susceptibility to noise, causing reduced accuracy and potential information loss in deep networks. In order to address these limitations, this study introduces a novel multi-lobar artificial neural network (MLANN) architecture inspired by the brain’s lobar processing of sensory information, aiming to improve the accuracy and efficiency of estimating concrete compressive strength. The MLANN framework employs various architectures of hidden layers, referred to as “lobes,” each with a unique arrangement of neurons to optimize data processing, reduce training noise, and expedite training time. Within the study context, an MLANN is developed, and its performance is evaluated to predict the compressive strength of concrete. Moreover, it is compared against two traditional cases, ANN and ensemble learning neural networks (ELNN). The study results indicated that the MLANN architecture significantly improves the estimation performance, reducing the root mean square error by up to 32.9% and mean absolute error by up to 25.9% while also enhancing the A20 index by up to 17.9%, ensuring a more robust and generalizable model. This advancement in model refinement can ultimately enhance the design and analysis processes in civil engineering, leading to more reliable and cost-effective construction practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is one of the most widely utilized construction materials globally, largely due to its availability and the ease of sourcing local materials1,2. With coarse and fine aggregates like stones and sand, along with cement, water, and chemical admixtures, concrete offers a cost-effective and durable solution that requires limited skilled labor for its application. Nevertheless, these properties contribute to its inherent heterogeneity, resulting in a nonlinear behavior under compressive stress. Existing destructive experimental methods that offer a reliable approach to determining this property are time-consuming and labor-intensive3,4. Accordingly, developing models for accurate predictions of compressive strength enables efficient resource allocation and time-effective construction practices, while imprecise estimations can lead to structural failures or overdesign, with significant economic implications5,6.

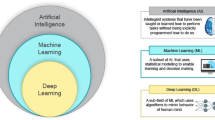

Recently artificial neural networks (ANNs) have emerged as promising tools for predicting material properties, including the compressive strength of concrete, owing to their ability to model complex nonlinear relationships within datasets7,8,9,10,11,12. Conventional ANN consists of interconnected layers based on a mathematical structure13. The architecture starts with an input layer vector, which connects to one or more hidden layer vectors, ultimately leading to an output layer vector. Each layer contains units called neurons (nodes), which gives rise to the term “neuron” in the context of artificial neural networks. These neurons are linked through weights and numerical values that define the strength of connections between them14. During training, ANNs iteratively adjust these weights using feedforward and backward propagation to improve performance15. Activation functions such as step, linear, sigmoid, and rectified linear functions enable the network to handle nonlinear problems16, while bias values better capture real-world data patterns17,18.

Despite their potential, conventional ANNs face limitations when applied to large datasets. These challenges include extended training times, susceptibility to noise, and potential information loss in deep networks, all of which compromise the accuracy and reliability of predictions19,20. Recent research has sought to use alternative machine learning techniques, such as bagging and boosting methods, to predict the strength and performance of concrete materials and structures21,22,23,24,25. Accordingly, there is still a gap in developing architectures that improve the accuracy and robustness for predicting concrete compressive strength with a large dataset.

In order to address these challenges, this study introduces a novel multi-lobar artificial neural network (MLANN) architecture inspired by the brain’s lobar processing of sensory information. This approach integrates multiple “lobes,” each with a distinct arrangement of neurons, designed to enhance data processing efficiency, reduce noise during training, and improve generalization capabilities. Unlike conventional ANNs, the MLANN framework provides a robust and adaptable solution for handling nonlinear datasets while maintaining a computationally efficient structure. The proposed MLANN is evaluated through comprehensive experiments to predict the compressive strength of concrete, utilizing a dataset with diverse mixture compositions. The methodology incorporates data normalization, shuffling, and unique weight initialization strategies to optimize training. The study employs the SoftPlus activation function to aggregate outputs from all lobes. Performance metrics such as root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and the A20 index are utilized to benchmark the MLANN against traditional multi-layer ANNs and ensemble learning neural networks (ELNN). By addressing the shortcomings of existing models and presenting a robust alternative, this study underscores the potential of MLANNs in advancing predictive modeling in civil engineering. The findings contribute to the broader application of brain-inspired computational frameworks in material science, paving the way for more reliable and cost-effective construction practices.

Research significance

Existing destructive testing methods, while reliable, are time-intensive procedures, creating a need for efficient, accurate, and cost-effective alternatives. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have shown promise in this domain, but their application is often hindered by challenges such as extended training times, noise susceptibility, and accuracy limitations when dealing with large nonlinear datasets. In order to address these shortcomings, this research introduces a novel multi-lobar artificial neural network (MLANN) architecture inspired by the brain’s lobar processing of sensory information. The MLANN framework enhances data processing, reduces training noise, and improves generalization capabilities, resulting in a model that significantly outperforms conventional ANNs and ensemble learning neural networks. This advancement holds substantial implications for civil engineering, as accurate and efficient predictions of concrete compressive strength enable better design, analysis, and construction practices. The findings contribute to material science and also to the broader application of bio-inspired computational frameworks.

Proposed neural network architecture

The human brain processes sensory information through a complex network of neurons, where different regions, known as lobes, manage specific aspects of incoming nerve impulses26. This lobar processing allows the brain to handle complex tasks efficiently. Traditional ANNs, Fig. 1, typically rely on straightforward input-output pathways, which can be inadequate for handling large datasets and complex problems without significant computational overhead. These conventional ANNs often require deep networks to achieve satisfactory results, leading to lengthy training times and increased susceptibility to noise, which can compromise accuracy.

For a traditional ANN architecture, the process within a single layer \(\:l\) can be mathematically represented as:

where \(\:{a}^{l-1}\) is the input (or activations from the previous layer); \(\:{W}^{l}\) is the weight matrix; \(\:{b}^{l}\) is the bias vector; \(\:f\) is the activation function; \(\:{a}^{l}\) is the output of layer \(\:l\). For an ANN with \(\:L\) layers, the final output \(\:y\) is:

In order to address these limitations, ensemble learning neural networks (ELNNs) have been previously developed, as shown in Fig. 2. ELNNs aggregate multiple models through an ensemble layer to improve predictive performance. The ELNN’s operation involves multiple sub-models \(\:i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,M\), each producing an output \(\:{y}_{i}\):

The final output of the ELNN is obtained by combining the outputs of all sub-models using an aggregation function \(\:g\), such as a weighted sum:

However, they can introduce interdependencies between models, potentially propagating noise and reducing training efficiency. Accordingly, this study develops an MLANN framework to replicate the brain’s biological mechanisms and functionalities for processing data structures in machine learning tasks.

The proposed MLANN architecture, depicted in Fig. 3, is inspired by the brain’s lobar structure. In this regard, each lobe in the MLANN functions as an independent processing unit capable of addressing specific nonlinearities in diverse datasets. In the MLANN, the operation of each lobe \(\:k=\text{1,2},\dots\:,N\) can be described as:

where \(\:{z}_{k}\) is the output of the \(\:k\)-th lobe; \(\:{W}_{k}\) and \(\:{b}_{k}\) are the weights and biases specific to that lobe; \(\:{f}_{k}\) is the activation function used within the lobe.

The outputs of all lobes are then aggregated using a function \(\:h\), such as the SoftPlus activation function:

This design inherently promotes adaptability and scalability, enabling the incorporation of various types and functions within a single model without relying on deep layering. In the MLANN, each lobe consists of its own set of layers and neurons, allowing it to process input data independently before combining the outputs. This modular approach enhances flexibility and improves noise control during training compared to conventional methods. The independent lobes reduce the risk of noise propagation, as each lobe can specialize in learning different patterns or features within the data.

The MLANN algorithm, as described in Algorithm 1, outlines the procedure for training a model for regression tasks. While it follows many conventional ANN practices, it includes specific steps for this framework. Initially, the data is shuffled randomly to eliminate any inherent order that could bias the training process. The shuffled data is then divided into training and testing sets.

Both sets are normalized to ensure consistent scaling, which can improve the MLANN’s convergence speed and overall performance. The weights and biases of the MLANN are initialized randomly, with each lobe starting from a different seed. Each neuron in the MLANN employs an activation function to introduce nonlinearity into the model. During forward propagation, the input data passes through the MLANN, progressing through each lobe and layer, to produce a regression output. This process involves multiplying the inputs by the weights, adding biases, and applying activation functions at each neuron.

In the output layer, the SoftPlus activation function is utilized to aggregate the effects of all lobes, combining their outputs into a single regression result. Optimization techniques are then applied to minimize the loss function with respect to the network’s weights and biases27,28. Finally, the optimized weights and biases are saved, and the model’s performance is evaluated using the testing dataset to assess its generalization capability.

Materials and methods

Developed database

In order to assess the proposed approach’s capabilities in estimating the compressive strength of concrete, a dataset with a large sample size was utilized. This dataset was adopted extensively in similar research in the past29,30,31,32,33. Table 1 depicts the descriptive statistics of the adopted dataset. Generally, it consists of 1005 mixtures with their compressive strengths at different ages. The input features for each of the investigated neural network models included the materials used in each concrete specimen, while the compressive strength of concrete was chosen as the prediction model’s output. Figure 4 shows a correlation analysis of the features in the dataset.

Investigated models

This study compares three different architectures, ANN, ELNN, and MLANN, to highlight the latter’s performance in enhancing the estimation accuracy in the case of compressive strength of concrete. During the training phase, the primary focus in these models was to minimize the loss function, which was taken as the normalized root mean squared error. In general, all models were independently constructed using the TensorFlow library in Python. The Pandas library was used for dataset management, while the NumPy library was utilized to handle post-training mathematical calculations. To ensure a robust comparison, the following conditions were maintained:

-

The ANN, ELNN, and MLANN cases adopted the same activation functions where the leaky rectified linear units (Leaky ReLU) were used in the hidden layers, and the SoftPlus was used in the output layer.

-

The parameters (weights and biases) for each model were initialized using the GlorotNormal function to prevent confounding factors. In order to address the variability in parameter initialization, each model underwent 1000 training cycles, each using a different randomization seed on normalized datasets. The best performance across these training cycles was considered for comparison.

-

The investigated models utilized backward propagation with the Nadam optimizer while maintaining uniform learning rates and batch sizes.

-

The ANN architecture was optimized with 10 hidden layers, each with 50 neurons. The MLANN architecture was composed of four lobes to produce a comparable case, where the first lobe had one hidden layer, the second lobe had two hidden layers, the third lobe had three hidden layers, and the fourth lobe had four hidden layers with each hidden layer in the MLANN containing 50 neurons. As a result, both the ANN and MLANN had an identical total number of neurons. Finally, the ELNN had the same structure as the MLANN with the same number of hidden neurons and hidden layers but with the exception of having an ensemble layer before the final output to aggregate the sub-models directly.

-

The database was randomly split into 70% training dataset and 30% testing dataset. In order to avoid any overfitting due to data splitting, the training was repeated 1000 times, each with a different random seed, meaning that the training and testing datasets were randomly changed 1000 times to ensure that the model accuracy is not affected by the data splitting and the selection of the random seed.

As a further investigation, linear regression, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbor, decision tree, random forest, adaptive boosting, and gradient boosting models were developed on the same dataset to benchmark the proposed approach performance against alternative machine learning techniques.

Performance assessment metrics

In order to evaluate the performance of the developed models herein, four different metrics were utilized, including the coefficient of determination (R2), Eq. (7), the root-mean-square error (RMSE), Eq. (8), the mean absolute percentage error (MAE), Eq. (10), and the A20 index which measures the percentage of predictions that fall within 80% accuracy of the actual values, Eq. (10). The A20 index typically ranges from 0 to 100%, with the latter being the best scenario where 100% of the predictions are within 80% accuracy while the earlier being the worst case.

where \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the true value; \(\:{\stackrel{-}{x}}_{i}\) denotes the average of the true values; \(\:{y}_{i}\) refers to the predicted value; \(\:n\) is the total count of data points; \(\:1\left(\bullet\:\right)\) is an indicator function that equals 1 if the condition inside is true, and 0 otherwise.

Results and discussions

Figures 5, 6 and 7 illustrate the density charts depicting the training progress of the developed models for predicting compressive strength. These figures were produced using the Datashader and Matplotlib libraries in Python and then formatted in PowerPoint. Specifically, Fig. 5 presents the results for the ANN case, Fig. 6 depicts the results for the ELNN case, and Fig. 7 shows the results for the proposed MLANN case. As mentioned before, to ensure a rigorous comparison, each model underwent 1000 training cycles. This approach was chosen to produce mean training curves that mitigate potential biases arising from the initial parameter settings. Examination of these figures reveals that, after completing the iterative optimization of weights and biases, all models achieved a comparable reduction in the loss function. Despite this similarity, the MLANN demonstrated superior performance in terms of accuracy. It reached comparable levels of precision with fewer training iterations compared to both the ANN and ELNN. One notable advantage of MLANN was its enhanced robustness in the effects of parameter initialization. The MLANN consistently showed greater resilience, whereas the ANN and ELNN exhibited sensitivity to fluctuations during training, with the latter having a slighter effect. This sensitivity can be attributed to the ANN’s larger number of weight vectors and the ELNN’s ensemble layer, which introduce additional complexity and noise during the initial data processing stages. As a result, the performance of the ANN and ELNN was more prone to variability due to the iterative optimization of a greater number of parameters. On the other hand, the MLANN, with its shallower architecture involving multiple lobar, managed to handle this noise more effectively, leading to a more stable training process and better accuracy. This difference underscores the potential advantages of the MLANN in scenarios where resilience to stabilized training and accuracy is critical.

Although both regression models achieved similar magnitudes of loss function during the training process, their performance diverged significantly when evaluated on the testing data. Figures 8, 9 and 10 illustrate the calculated versus measured compressive strength values predicted by the investigated models.

The results show that the ANN, ELNN, and MLANN models fit the training data exceptionally well, with R2 values around 99%. However, a different picture emerges with the testing data, where traditional cases underperformed compared to the MLANN. Specifically, the ANN achieved an R2 of approximately 90% on the testing data, while the ELNN reached an R2 of about 88%, and the MLANN produced an R2 of about 94%. This discrepancy can be attributed to overfitting in the ANN, likely caused by the noise introduced by its 10 hidden layers and the existence of an ensemble layer. In contrast, the MLANN mitigates these issues, leading to better generalization and performance on the testing data.

The performance assessment of the models, as shown in Fig. 11, highlights the variation between training and testing phases across all metrics and models. It can be seen that the MLANN demonstrates significantly better performance in the testing phase compared to ANN and ELNN, with clear improvements in error reduction and R2 and A20 indices. In this regard, the MLANN reduces the RMSE in the testing case by 24.7% compared to the ANN (from 5.38 to 4.05 MPa) and by 32.9% compared to the ELNN (from 6.04 to 4.05 MPa). Similarly, the MLANN lowers the MAE in the testing case by 21.4% compared to the ANN (from 3.78 to 2.97 MPa) and by 25.9% compared to the ELNN (from 4.01 to 2.97 MPa). The R2 increases by 4.4% for the MLANN in the testing case over the ANN (from 0.90 to 0.94) and by 6.8% over the ELNN (from 0.88 to 0.94). Furthermore, the MLANN improves the A20 index by 17.9% over the ANN in the testing case (from 76.08 to 89.70%) and 14.4% over the ELNN (from 78.41 to 89.70%), indicating better accuracy and controlled overfitting and highlighting the superiority of the proposed technique over traditional cases.

Further comparisons with other alternative machine learning techniques for predicting the compressive strength of concrete are performed, and the results are reported in Table 2. It can be observed that the decision trees exhibit near-perfect training performance but suffer from overfitting, reflected in a drop in testing R2 and A20 index. Random forest and gradient boosting outperform the simpler models, demonstrating high testing R2 and superior generalization, with random forest giving an A20 index on testing data of 79.47% while gradient boosting gives 82.45%. When compared to ANN-based models, MLANN stands out as superior, achieving higher testing R2 (0.94), lower RMSE (4.05), and a significantly higher A20 index (89.70) than all other models in this analysis, including random forest and gradient boosting. ANN and ELNN, while performing well, show lower performance, reflecting marginally less reliability in error tolerance. In summary, while random forest and gradient boosting demonstrate strong performance among traditional methods, MLANN’s enhanced architecture makes it more effective for both training and testing phases, particularly in scenarios requiring precise and reliable predictions.

Conclusion

This study aims to develop a brain-inspired MLANN architecture for accurately estimating concrete compressive strength while addressing the limitations of traditional neural networks. Current approaches, such as ANNs and ELNNs, often struggle with overfitting and are susceptible to noise, which limits their ability to generalize to new data. This research introduces the MLANN model to enhance prediction accuracy and control overfitting, providing a more reliable and efficient solution. The study compares the performance of MLANN against ANN and ELNN models, demonstrating the superior generalization capability of the MLANN. Based on the aforementioned statements, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

MLANN achieves a faster reduction in the loss function with respect to the epoch number than ANN and ELNN.

-

MLANN improves R² by 4.4% over ANN and by 6.8% over ELNN in the testing phase, whereas it increases the A20 index by 17.9% compared to the ANN and by 14.4% compared to the ELNN, demonstrating improved prediction accuracy.

-

MLANN reduces the RMSE in the testing phase by 24.7% compared to the ANN and by 32.9% compared to ELNN, while it lowers the MAE by 21.4% compared to the ANN and by 25.9% compared to ELNN in the testing phase.

-

MLANN effectively controls overfitting and generalizes unseen data better than traditional ANN and ELNN models.

-

Further comparison with alternative machine learning techniques, including bagging and boosting, shows that the MLANN approach yields the highest accuracy, represented by the highest A20 index and lowest RMSE and MAE values in both training and testing cases.

Finally, the study has certain limitations. The dataset used primarily focuses on compressive strength prediction, and the model’s performance needs to be validated across other datasets and different material properties to confirm its versatility. Future research should also explore the integration of different activation functions and hybrid approaches with other machine learning techniques to further enhance the MLANN’s adaptability and robustness.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abuodeh, O. R., Abdalla, J. A. & Hawileh, R. A. Assessment of compressive strength of Ultra-high performance concrete using deep machine learning techniques. Appl. Soft Comput. 95, 106552 (2020).

Hassoun, M. N. & Al-Manaseer, A. Structural Concrete: Theory and Design Wiley. (2020).

Paudel, S., Pudasaini, A., Shrestha, R. K. & Kharel, E. Compressive strength of concrete material using machine learning techniques. Clean. Eng. Technol. 15, 100661 (2023).

Chi, L. et al. Machine learning prediction of compressive strength of concrete with resistivity modification. Mater. Today Commun. 36, 106470 (2023).

Habib, A., Houri, A. A., Junaid, M. T. & Barakat, S. A systematic and bibliometric review on physics-based neural networks applications as a solution for structural engineering partial differential equations. In Structures. Elsevier, 107361. (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Prediction of alkali-silica reaction expansion of concrete using artificial neural networks. Cem. Concr. Compos. 140, 105073 (2023).

Habib, M., Bashir, B., Alsalman, A. & Bachir, H. Evaluating the accuracy and effectiveness of machine learning methods for rapidly determining the safety factor of road embankments. Multidiscipl. Model. Mater. Struct. 19 (5), 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1108/MMMS-12-2022-0290 (2023).

Golhani, K., Balasundram, S. K., Vadamalai, G. & Pradhan, B. A review of neural networks in plant disease detection using hyperspectral data. Inform. Process. Agric. 5 (3), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2018.05.002 (2018).

Habib, M., Habib, A., Albzaie, M. & Farghal, A. Sustainability benefits of AI-based engineering solutions for infrastructure resilience in arid regions against extreme rainfall events. Discov. Sustain. 5 (1), 278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00500-2 (2024).

Pietrzak, P., Szczęsny, S., Huderek, D. & Przyborowski, Ł. Overview of spiking neural network learning approaches and their computational complexities. Sensors 23 (6), 3037 (2023).

Houri, A. L., Habib, A. & Al-Sadoon, Z. A. A., Artificial Intelligence-Based Design and Analysis of Passive Control structures: an overview. J. Soft Comput. Civil Eng., 145–182. (2024).

Shrif, M., Al-Sadoon, Z. A., Barakat, S., Habib, A. & Mostafa, O. Optimizing gene expression programming to Predict Shear Capacity in Corrugated web steel beams. Civil Eng. J. 10 (5), 1370–1385 (2024).

Mater, Y., Kamel, M., Karam, A. & Bakhoum, E. ANN-Python prediction model for the compressive strength of green concrete. Constr. Innov. 23 (2), 340–359 (2023).

Kufel, J. et al. What is machine learning, artificial neural networks and deep learning? —Examples of practical applications in medicine. Diagnostics 13 (15), 2582 (2023).

Teke, C., Akkurt, I., Arslankaya, S., Ekmekci, I. & Gunoglu, K. Prediction of gamma ray spectrum for 22Na source by feed forward back propagation ANN Model. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 202, 110558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2022.110558 (2023).

Hecht-Nielsen, R. Theory of the backpropagation neural network. In Neural Networks for Perception. Academic, 65–93. (1992).

Sharma, S., Sharma, S. & Athaiya, A. Activation functions in neural networks. Towards Data Sci. 6 (12), 310–316 (2017).

Koçak, Y. & Şiray, G. Ü. New activation functions for single layer feedforward neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 164, 113977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113977 (2021).

Amit, D. J. & Amit, D. J. Modeling Brain Function: The World of Attractor Neural Networks Cambridge University Press. (1989).

Schmidgall, S. et al. Brain-inspired learning in artificial neural networks: a review. APL Mach. Learn, 2(2). (2024).

Khan, M. A. et al. Compressive strength of fly-Ash‐based Geopolymer concrete by Gene expression programming and Random Forest. Adv. Civil Eng. 2021 (1), 6618407 (2021).

Li, H., Lin, J., Lei, X. & Wei, T. Compressive strength prediction of basalt fiber reinforced concrete via random forest algorithm. Mater. Today Commun. 30, 103117 (2022).

Habib, A., Barakat, S., Al-Toubat, S., Junaid, M. T. & Maalej, M. Developing machine learning models for identifying the failure potential of fire-exposed FRP-strengthened concrete beams. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09497-2 (2024).

Arunadevi, M., Rani, M., Sibinraj, R., Chandru, M. K. & Prasad, C. D. Comparison of k-nearest neighbor & artificial neural network prediction in the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Zhang, H., Gu, X., Zhang, F. & Zhang, L. Development of a radial basis neural network for the prediction of the compressive strength of high-performance concrete. Multiscale Multidiscipl. Model. Exp. Des. 7 (1), 109–122 (2024).

Mather, G. Essentials of Sensation and Perception Routledge. (2014).

Wang, Q., Ma, Y., Zhao, K. & Tian, Y. A comprehensive survey of loss functions in machine learning. Ann. Data Sci.. 1–26. (2020).

Alibrahim, B. & Uygar, E. Modelling of soil–water characteristic curve for diverse soils using soil suction parameters. Acta Geotech. 18 (8), 4233–4244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01821-8 (2023).

Yeh, I. C. Modeling of strength of high-performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Cem. Concr. Res. 28 (12), 1797–1808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2007.04.009 (1998).

Yeh, I. C. Analysis of strength of concrete using design of experiments and neural networks. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 18 (4), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2006)18 (2006).

Ke, X. & Duan, Y. A bayesian machine learning approach for inverse prediction of high-performance concrete ingredients with targeted performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 270, 121424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121424 (2021).

Asteris, P. G., Skentou, A. D., Bardhan, A., Samui, P. & Pilakoutas, K. Predicting concrete compressive strength using hybrid ensembling of surrogate machine learning models. Cem. Concr. Res. 145, 106449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106449 (2021).

Habib, M. & Okayli, M. Evaluating the sensitivity of machine learning models to data preprocessing technique in concrete compressive strength estimation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-08776-2 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: B. A, (A) H., and M. H.; analysis and interpretation of results: (B) A, (A) H., and M. H.; draft manuscript preparation: (B) A. and A. H.; manuscript review & editing: M. H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alibrahim, B., Habib, A. & Habib, M. Developing a brain inspired multilobar neural networks architecture for rapidly and accurately estimating concrete compressive strength. Sci Rep 15, 1989 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84325-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84325-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chaotic analysis, hopf bifurcation and collision of optical periodic solitons in (2+1)-dimensional degenerated Biswas–Milovic equation with Kerr law of nonlinearity

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Compressive Strength Prediction of Geopolymers Using Stacking Ensemble and Fuzzy Splitting

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering (2025)