Abstract

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of oral and maxillofacial anomalies among newborns in the Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia, and to explore associations with parental health, socioeconomic status, and environmental factors. Given the scarcity of regional data on congenital anomalies, this research furthers the understanding of localised health risks and could inform targeted interventions. A cross-sectional hospital-based study was conducted involving 40,000 newborns born between December 2019 and June 2024. Data were collected from medical records and parental interviews at one of the main hospitals in the Ha’il Region. Anomalies were categorised and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Forty-seven cases (0.146%) of oral and maxillofacial anomalies were identified, with a higher prevalence seen in female newborns. Relationship were found between these anomalies and parental smoking, socioeconomic status, and parental health history. Anomalies, such as cleft lips and palates, were more frequent in females, while other conditions, like the eruption of chlorodontia, were exclusive to males. This study underscores the importance of addressing environmental and socioeconomic factors to prevent congenital anomalies. These findings provide crucial data for healthcare planning in the Ha’il Region, aligning with Saudi’s Vision 2030 objectives related to improving neonatal and maternal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of congenital anomalies in neonates is a critical area of study within public health. Congenital anomalies, which include a wide range of structural and functional disorders present at birth, can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life1. Additionally, these anomalies pose substantial challenges for healthcare systems. Understanding the prevalence of these conditions and their associated risk factors is essential for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies1,2. In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Health has emphasised the importance of regional prevalence data as part of its Vision 2030 initiative, which aims to enhance the quality of healthcare and ensure reasonable health services are provided across the kingdom. This initiative highlights the need for localised data to inform policy-making and resource allocation.

Despite global recognition of the importance of monitoring congenital anomalies, data specific to the Ha’il region of Saudi Arabia remains scarce. Ha’il is a region with unique demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and thus may present distinct patterns of congenital anomalies compared to other parts of the country. Given the emphasis on regional health assessments by the Ministry of Health, it is imperative to investigate the prevalence of congenital anomalies in neonates born in Ha’il. Such data will contribute to the national database and help local healthcare providers tailor their services to meet the specific needs of the population.

To guide this investigation, a PEO question has been formulated: In neonates born at one of the main hospitals in the Ha’il Region between December 2019 and June 2024 (Population), what is the prevalence of oral and maxillofacial congenital anomalies (Outcome), and how are these anomalies associated with various demographic and maternal risk factors (Exposure)?

The findings from this study are expected to have several important implications. First, they will provide valuable data to the Ministry of Health, contributing to the national effort to map the prevalence of congenital oral and maxillofacial anomalies across different regions. This information is crucial for planning and implementing healthcare services, particularly maternal and neonatal care services. Second, the study will help local healthcare providers understand the specific needs of the Ha’il population, enabling them to offer more personalised and effective care. Finally, by identifying key risk factors, the study will contribute to the broader body of knowledge on congenital oral and maxillofacial anomalies, supporting global efforts to prevent and manage these conditions.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

The present study was conducted in one of the main hospitals in the Ha’il Region of Saudi Arabia. Data were retrieved from the oral and maxillofacial surgery department and the maternity department. This cross-sectional hospital-based study involved a comprehensive review of medical records, and the study period covered four and a half years, from December 2019 to June 2024. This period was chosen to provide a substantial dataset that reflected recent trends and enabled a thorough examination of longitudinal data. All newborn patients diagnosed with oral and maxillofacial anomalies within the study period were eligible for inclusion. Patients whose records indicated that the anomalies were diagnosed after the neonatal period were excluded.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Approval Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, prior to study commencement (IRB approval number: H-2023-439). This project performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations and adhered to the ethical standards laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the newborns included in the study before conducting interviews and administering questionnaires.

Data collection procedure and outcome measures

The study utilized the hospital’s electronic health records (EHR) coding program, which is specifically equipped to retrieve patient records using keywords and diagnostic codes. To identify newborns with oral and maxillofacial anomalies, we applied relevant ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes and specific keywords associated with these anomalies, such as “cleft palate,” “natal teeth,” and “Epstein pearls”.

The parents of newborns identified with oral and maxillofacial anomalies were contacted primarily through phone calls, with follow-up attempts made if initial contact was unsuccessful. Each family was contacted up to three times to encourage participation, and efforts were made to reach them during various times of the day to accommodate different schedules. Of the contacted families, 100% agreed to participate in the study. Verbal consent was obtained from each participating parent before beginning the interview, ensuring compliance with ethical standards and respect for parental willingness. The questionnaire covered various aspects, including demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, and parental socioeconomic status); birth details (gestational age, birth, mode of delivery, and any complications during birth); medical history (family history of congenital anomalies, maternal health during pregnancy, and prenatal care); intraoral examination findings (detailed examination of oral and maxillofacial anomalies observed at birth); nutritional information (feeding practices and any difficulties encountered due to oral and maxillofacial anomalies); parental information (age of parents, consanguinity, and parental health conditions); diagnostic tests and procedures (any imaging or laboratory tests conducted to diagnose the anomalies); and follow-up and treatment records (details of any surgical or non-surgical interventions, follow-up visits, and outcomes).

The survey with parents was conducted within a short period following the birth of the newborns, as part of the study’s cross-sectional design. This approach was chosen to minimize recall bias, especially for details related to pregnancy and early neonatal health. All data collection occurred within the study period from December 2019 to June 2024, ensuring that parents were surveyed within a few years after birth, thus reducing the likelihood of inaccurate recall. Additionally, specific questions about pregnancy and early life health were structured to facilitate accurate responses and mitigate the impact of recall limitations.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage were used to summarise the prevalence of various oral and maxillofacial anomalies and demographic characteristics of the study population.

Results

Through this systematic coding search, approximately 40,000 records were initially reviewed from December 2019 to June 2024 to identify the presence of oral and maxillofacial anomalies. These included cleft lip and palate, cleft palate, cleft lip, Epstein pearls, Bohn’s nodules, natal teeth, neonatal teeth, and other related conditions. Each record flagged by the coding program underwent individual chart reviews by trained researchers to verify the presence of oral and maxillofacial anomalies. This meticulous process ensured accuracy and adherence to inclusion criteria, ultimately identifying 47 cases that met the study’s diagnostic requirements (0.146%). The gender distribution revealed that 20 (42.6%) of the newborns were male, while 27 (57.4%) were female. Regarding birth year distribution, 3 cases (6.4%) were born in 2019, 6 (12.8%) in 2020, 13 (27.7%) in both 2021 and 2022, 8 (17.0%) in 2023, and 4 (8.5%) in 2024. Table 1 summarises these findings.

Anomaly types and distribution

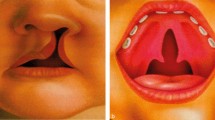

The identified oral and maxillofacial anomalies included natal teeth (4 cases, 8.5%), neonatal teeth (8 cases, 17.0%), Epstein pearls (3 cases, 6.4%), a combination of neonatal teeth and cleft palate (1 case, 2.1%), eruption of a chlorodontia (1 case, 2.1%), eruption cyst (1 case, 2.1%), cleft lip (11 cases, 23.4%), cleft palate (7 cases, 14.9%), cleft lip and palate (5 cases, 10.6%), cleft lip, palate and alveolus (2 cases, 4.3%), microlip (2 cases, 4.3%), oronasal fistula (1 case, 2.1%), and a combination of cleft palate and oronasal fistula (1 case, 2.1%). Regarding the anatomical location of these anomalies, 13 cases (27.7%) were found in the lower jaw, 1 case (2.1%) in the upper jaw, 13 cases (27.7%) in the lip, 14 cases (29.8%) in the palate, 5 cases (10.6%) involved both the lip and palate, and 1 case (2.1%) involved both the lower jaw and palate (Table 1). The family history, physical characteristics, parental and environmental factors are also reported in this study (Table 1).

Treatment and outcomes

The treatments provided included extraction in 13 cases (27.7%), surgery in 29 cases (61.7%), and follow-ups in 5 cases (10.6%). The outcomes of the treatments were satisfactory in 46 cases (97.9%) and unsatisfactory in 1 case (2.1%).

Various oral and maxillofacial anomalies were more commonly observed in female newborns compared to males with exception the eruption of chlorodontia and eruption cysts, Cleft lip, palate, and alveolus and Eruption cyst were exclusively observed in male newborns (100.0%). However, combined cleft lip and palate anomalies showed a higher occurrence in males (60.0%) than in females (40.0%). Statistical analyses indicated a significant association between gender and the occurrence of these anomalies (p-value = 0.033) as shown in Table 2. Statistical analyses indicated a significant association between these anomalies and parental smoking habits (p-value = 0.016). The association between various oral and environmental factors, socioeconomic status and parental health history revealed distinct pattern as exposed in Table 3. Statistical analyses indicated a significant association between these anomalies and parental smoking habits (p-value = 0.016). Additionally, statistical analyses indicated a significant association between the type of anomalies and socioeconomic status (p-value = 0.031). Furthermore, The findings were statistically significant (p-value = 0.001) in relation to parental health history and anomalies as reported in Table 3.

Discussion

The most prevalent anomalies in various nations have been the subject of earlier studies3,4,5,6,7,8. Data on the prevalence of anomalies in the Saudi population is, nevertheless, lacking. However, it is concerning that the Hail district, which is in the northern area, has not been thoroughly examined to determine the frequency of anomalies among its residents. Therefore, determining the frequency of anomalies and their effects is crucial because it will allow dentists to take preventative and restorative actions, which could greatly enhance the quality of life associated with oral health.

Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of congenital anomalies can vary significantly based on factors such as maternal age, socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, and healthcare access3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Studies have also highlighted variability in the types of oral abnormalities found across different populations. For instance, research in Mexico noted high prevalence rates for congenital oral cysts and ankyloglossia4, while studies in Iran and India identified associations with parental factors, such as consanguinity and maternal health10,11. These studies underscore the importance of regional research in understanding specific patterns and correlations relevant to different populations. Table 4 summarises the findings from studies in different countries, with the percentage of oral and maxillofacial anomalies ranging from 0.14% in Canada to 50% in Brazil. By comprehensively analysing these variables, our study aimed to provide a nuanced understanding of the risk factors associated with congenital oral and maxillofacial anomalies in the Ha’il region. The results of our current investigation showed that 0.14% of the included patients had oral and maxillofacial anomalies. A complex interplay of genetic, developmental, and environmental factors was revealed following the epidemiological examination of oral and maxillofacial anomalies in neonates and their association with parental health. The research publications offer a thorough analysis of these anomalies and emphasise the importance of early discovery, multidisciplinary care, and genetic counselling12,13.

Studies on the prevalence of developmental anomalies aid in determining occurrence rates, monitoring changes over time, identifying shifts in patterns, and identifying potential incidence causes. Diagnosing developmental anomalies helps identify syndromes and/or related systemic diseases. There is limited research available on the prevalence of congenital anomalies in the Ha’il region of Saudi Arabia. This research provides insight that could improve the detection of abnormalities in the Ha’il region.

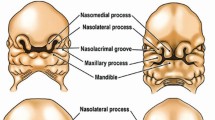

The current research revealed a high frequency of oral cavity anomalies in infants. The most common characteristic observed was the presence of orofacial clefts. However, the association between orofacial clefts in newborns and parent-related variables require further investigation. According to Hlongwa et al.14, 303,000 newborn infants died within four weeks after birth due to congenital anomalies globally. The most frequent anomaly of the orofacial region is orofacial clefts, with a prevalence of 1 case per 700 live births. Hlongwa et al. assessed 699 cases of children in South Africa with orofacial clefts. These children had a median age of 3 years, and 133 were found to have cleft lips, 247 were found to have cleft palates, and 305 had both14. According to the 2024 Global Oral Health Status Report from the World Health Organization, around 3.5 billion individuals are impacted by oral diseases globally. Orofacial clefts occur in approximately 1 out of every 1000–1500 births worldwide4. Yow et al.15 found that out of every 10,000 births, the orofacial cleft prevalence was 17.72 for male children and 15.78 for female children. During the study, out of 363,633 live births, 115 newborns were found to have a cleft lip, 249 newborns had a cleft palate, and 244 newborns had both. Of the 115 infants born with a cleft lip, 72 (62.6%) were boys and 43 (37.4%) were girls. Of the 249 infants with cleft palates, 97 (39%) were boys and 152 (61%) were girls. Of the 244 infants with orofacial clefts, 143 (58.6%) were boys and 101 (41.4%) were girls. These results are consistent with the current findings. Temporal variations in embryological development are thought to cause these gender differences in cleft phenotypes. This is illustrated by the fact that in Yow et al.’s study, females had a higher chance of demonstrating issues with the secondary palate or cleft palate due to their palatal development being slower compared to males. Therefore, gender is a risk factor for the occurrence of orofacial clefts15.

Income and socioeconomic status have been suggested as potential risk factors for orofacial cleft development. It has been suggested that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to experience orofacial clefts16,17, with recent studies confirming this link18.19. However, other studies have reported no association between lower socioeconomic status and orofacial cleft risk. The limited amount of prior research, the narrow study scope, and the presence of confounding variables ( such as nutritional deficiencies and alcohol abuse) all further weaken the existing evidence. It is important to comprehend how socioeconomic status is connected to the development of orofacial clefts, as being diagnosed with a cleft can lead to decreased chances of employment and perpetuate the cycle of poverty if not addressed16. Our findings confirm what previous studies have found, which is that being of middle socioeconomic status and various environmental factors are the most important factors influencing the mouths of newborns.

Natal teeth are present from birth, while neonatal teeth emerge in the oral cavity within the first month of life20. Natal teeth are uncommon in extremely premature newborns21. In the current study, 8.5% of newborns had natal teeth, and 17.0% had neonatal teeth. The lower primary central incisors are the teeth most frequently natal, with an 85% prevalence21. This aligns with the typical sequence of primary deciduous teeth eruption21. The goal of treatment and management should be to preserve the teeth in a healthy mouth for cosmetic reasons and to ensure there is enough space for permanent teeth to come through. These facts align with the outcome of our study. Dyment et al. recommended that the level of gum attachment and need for anaesthesia should be assessed before removing natal teeth22. They suggested that when there is minimal gingival attachment, sufficient soft tissue anaesthesia can be achieved using topical anaesthetic for extraction procedures. The presence of teeth from birth or shortly after birth requires a prompt and precise diagnosis to determine whether it is best to keep the teeth or remove them. Additionally, the patient needs to be evaluated for any potential systemic or syndromic connections, and if necessary, a paediatric appointment should be scheduled.

Epstein pearls were found in 6.4% of the current cases, while microlips were found in 4.3% and oronasal fistulas in 2.1%. This finding aligns with the findings of Vaz et al.’s1 study while contradicting George et al.’s22 study. George et al. identified Bohn’s nodules as the most common inclusion cyst. Other studies have indicated that children who have buccal nodules from birth are more likely to experience oral Streptococcus mutans colonisation early on, which could increase the risk of cavities due to the nodules being associated with biofilm buildup2.

In the current study, the intraoral features identified did not show any association with most of the newborns or parental factors assessed. However, Epstein’s pearls were linked to paternal smoking and gestational age, while Bohn’s nodules were associated with the male gender. Cetinkaya et al.2 examined how the features and changes in a newborn’s oral cavity are linked to factors like medical problems during pregnancy, maternal health conditions, smoking or drug use during pregnancy, and parental consanguinity. They demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between the occurrence of oral cysts and diabetes, insulin use while pregnant, parental consanguinity, and tobacco use during pregnancy2. However, these findings are not definitive. Other studies have indicated no statistically significant association between the occurrence of inclusion cysts and a baby’s weight23, gender24, birth weight, pregnancy length, or factors associated with delivery24. Further research is needed to investigate the factors linked to these oral conditions.

An examination of biopsies obtained from the oral and jaw regions of Malaysian newborns and infants provided insights into common patterns and variations in the observed anomalies12. Inflammatory/reactive lesions were the most prevalent, followed by tumour/tumour-like lesions and then cystic/pseudocystic lesions. Of the tumour/tumour-like lesions, congenital epulis was the most common. This implies that certain abnormalities could be present from birth, possibly affected by genetic factors passed down from parents. Children with craniofacial issues, such as cleft lips and palates, are at a higher risk of developing tooth decay and gum disease5. A high incidence of oral cysts (94%) was found in newborns in Taiwan, with no notable link to gender, weight, or gestational age21.

Through an extensive examination of these variables, our research sought to offer a sophisticated comprehension of the risk factors linked to congenital oral and maxillofacial anomalies in the Ha’il region. This approach will help identify high-risk groups and inform targeted prevention and intervention strategies. Significant clinical implications of congenital oral and maxillofacial anomalies span the functional, psychological, and developmental domains in addition to physical health. Long-term follow-up, interdisciplinary management, and early diagnosis are crucial for maximizing results and enhancing the lives of those impacted.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The small sample size, influenced by the low prevalence of oral and maxillofacial anomalies, limits the applicability of certain findings and impairs the ability to draw definitive interpretations. about associations between specific variables and intraoral data. Additionally, evaluations conducted shortly after birth may not capture anomalies that develop later or the progression of already diagnosed conditions. The lack of extensive research in this field further limits comparisons with existing data. Future studies should address these limitations by recruiting larger sample sizes from broader regions within Saudi Arabia to improve statistical power and representativeness. Longitudinal studies are also recommended to explore the progression and causative factors of these anomalies over time, providing a more comprehensive understanding. It is better in the future to have a qualitative study design for understanding the causal mechanism.

Conclusions

Under the limitations of this study, it could be concluded that different anomalies can be seen in infants’ mouths. It is important for healthcare providers to recognise these so they can provide appropriate treatment if needed and avoid unnecessary interventions. This highlights the significance of timely and regular dental care for newborns and infants with these conditions to effectively manage their health. Timely identification, regular medical check-ups, and team-based strategies are crucial for the successful treatment of these abnormalities. Additional research is needed to explore how parental health factors directly affect the development of these anomalies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Chandler, C. L. et al. Intraoral findings in newborns: prevalence and associated factors. Braz. J. Oral Sci. e181344 (2019).

Cetinkaya, M. et al. Prevalence of oral abnormalities in a Turkish newborn population. Int. Dent. J. 61 (2), 90–100 (2011).

Bandaru, B. K. et al. The prevalence of developmental anomalies among school children in Southern district of Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 23 (1), 160 (2019).

De Oliveira, A. J., Duarte, D. A. & Diniz, M. B. Oral anomalies in newborns: an observational cross-sectional study. J. Dent. Child. 86 (2), 75–80 (2019).

Lee, J. W. & Chung, H. Y. Vascular anomalies of the head and neck: current overview. Arch. Craniofac. Surg. 19 (4), 243 (2018).

El Koumi, M. A., Al Banna, E. A. & Lebda, I. Pattern of congenital anomalies in newborn: a hospital-based study. Pediatr. Rep. 5 (1) (2013).

Baxter, D. J. G. & Shroff, M. M. Developmental maxillofacial anomalies. In Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 555–568 (WB Saunders, 2011).

Kos, M. Head and neck congenital malformations. Acta Clin. Croat. 43, 195–202 (2004).

Schembri, M. et al. Environmental and socioeconomic factors influence the live-born prevalence of congenital heart disease: a population-based study in Malta. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9 (7), e015255 (2020).

Bronoosh, P., Kasraeian, M. & Saeedi, B. G. Oral abnormalities in an Iranian newborn population. Pediatr. Dent. J. 24 (1), 8–11 (2014).

Thaddanee, R., Patel, H. S. & Thakor, N. A study on incidence of congenital anomalies in newborns and their association with maternal factors: a prospective study. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 3 (2), 579 (2016).

Binti Shuhairi, N. N. et al. A retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial biopsied specimens in Malaysian newborns and infants. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 31 (4), 496–503 (2021).

Assiry, A. A. et al. Head and neck congenital anomalies in neonate hospitals in Hail, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 13 (2), 160 (2020).

Hlongwa, P., Levin, J. & Rispel, L. C. Epidemiology and clinical profile of individuals with cleft lip and palate utilising specialised academic treatment centres in South Africa. PLoS ONE 14 (5), e0215931 (2019).

Yow, M., Jin, A. & Yeo, G. S. H. Epidemiologic trends of infants with orofacial clefts in a multiethnic country: a retrospective population-based study. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 7556 (2021).

Vu, G. H. et al. Poverty and risk of cleft lip and palate: an analysis of United States birth data. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 149 (1), 169–182 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Global, regional and national burden of orofacial clefts from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Ann. Med. 55 (1), 2215540 (2023).

Alfwaress, F. S. D. et al. Cleft lip and palate: demographic patterns and the associated communication disorders. J. Craniofac. Surg. 28 (8), 2117–2121 (2017).

Li, H. et al. A discriminant analysis prediction model of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate based on risk factors. BMC Pregn. Childbirth 16, 1–8 (2016).

Hebling, J., Zuanon, A. C. & Vianna, D. R. Natal and neonatal teeth: review of the literature. J. Dent. Child. (Chic) 79 (2), 73–76 (2012).

Gupta, R., Gupta, S. & Gupta, A. Nonsyndromic extremely premature eruption of teeth in preterm neonates: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 57 (9), 1062–1065 (2018).

George, D., Bhat, S. S. & Hegde, S. K. Oral findings in newborn children in and around Mangalore, Karnataka State, India. Med. Princ. Pract. 17 (5), 385–389 (2008).

Abanto, J. et al. Oral characteristics of newborns: report of some oral anomalies and their treatment. Int. J. Dent. 8 (3), 140–145 (2009).

Liu, M. H. & Huang, W. H. Oral abnormalities in Taiwanese newborns. J. Dent. Child. 71 (2), 118–120 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the financial support from the Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha'il Saudi Arabia through project number (RCP-24 198).

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha'il Saudi Arabia through project number (RCP-24 198).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AFA, AAM, and KAA contributed to the concept of the research, study design, data collection, supervision, statistical analysis, writing the original draft, and reading and editing the final paper. NAA, RBA, SFA , MAA, YEA, EAA, and FLA contributed to data collection, and writing the original draft. Every author evaluated and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol for this project was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Research Committee of the University of Ha’il, in compliance with institutional and national ethical standards for research involving human subjects. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Approval Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, prior to study commencement. This project performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations and adhered to the ethical standards laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the newborns included in the study before conducting interviews and administering questionnaires.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alshammari, A.F., Alhomayan, N.A., Alshmari, R.B. et al. An epidemiological investigation of oral and maxillofacial anomalies in newborns and their relation to parental health in the Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 15, 9010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84509-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84509-7