Abstract

Most of toolpaths for machining is composed of series of short linear segments (G01 command), which limits the feedrate and machining quality. To generate a smooth machining path, a new optimization strategy is proposed to optimize the toolpath at the curvature level. First, the three essential components of optimization are introduced, and the local corner smoothness is converted into an optimization problem. The optimization challenge is then resolved by an intelligent optimization algorithm. Considering the influence of population size and computational resources on intelligent optimization algorithms, a deep learning algorithm (the Double-ResNet Local Smoothing (DRLS) algorithm) is proposed to further improve optimization efficiency. The First-Double-Local Smoothing (FDLS) algorithm is used to optimize the positions of NURBS (Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline) control points, and the Second-Double-Local Smoothing (SDLS) algorithm is employed to optimize the NURBS weights to generate a smoother toolpath, thus allowing the cutting tool to pass through each local corner at a higher feedrate during the machining process. In order to ensure machining quality, geometric constraints, drive condition constraints, and contour error constraints are taken into account during the feedrate planning process. Finally, three simulations are presented to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of aerospace technology, many parametric curves and surfaces have been widely used to describe aerospace components due to their simple modeling and high-order continuity, including Bezier curves, NURBS splines, and PH curves. These provide a general mathematical tool for the analytical calculations. Although CNC machining paths can now be described by spline curves, most machining paths are still predominantly created using G01 commands. The tangential discontinuities between the line segments caused by the machining path's poor smoothness cause the machining feedrate to decrease to very low or even zero, with significant swings in the acceleration and jerk restrictions. Therefore, in order to improve machining efficiency, the machining path needs to be smoothed at the geometry level. Currently, smoothing methods are divided into two categories: local corner smoothing and global smoothing. Global smoothing, due to the complexity of error analysis and the difficulty of precisely controlling errors, remains challenges1,2,3. Most recent research has primarily focused on local corner smoothing.

The analytical calculation method is the most commonly utilized for local corner smoothing. References4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 have provided analytical calculations explaining the reasons why asymmetric local machining paths and symmetric local machining paths can enhance machining efficiency. These findings have been validated through experiments and simulations. The difference lies in the order of continuity, the degree of curves, the different applications, and the complexity of the calculation. Lu4 employed the PSO algorithm to optimize local velocity. However, the efficiency of the PSO optimization algorithm is affected by factors such as population size and computational resources, which can reduce the solution efficiency. Xu6 provided analytical calculations to give a method of how to control the approximation-error, but there is still room for optimization, which can still further optimize the curvature by adjusting the position of the control points. Huang7 proposed a real-time local corner smoothing method that significantly reduces the acceleration of each axis while simultaneously ensuring accuracy in the tool tip and tool axis vector errors. This method has been integrated into an open environment CNC system, validating its effectiveness. Hu8 et al. presented an analytically computed cubic continuous local smoothing method, which locally inserts B-spline curves to limit the maximum approximation error while performing local smoothing. It has been experimentally verified that the method has smoother acceleration and smaller contour errors. Hu9 verified why the overlapping spline curves are not smooth enough by the numerical and analytical calculations and proposed a method to remove overlapping asymmetric curves to smooth the curves, which significantly reduces the curvature and saves machining time. Han et al.15 performed analytical calculations while also conducting parameter sensitivity analysis on local control points at different angles, and S-shaped acceleration and deceleration planning was used to plan the residual distance between speed intervals in order to improve the machining efficiency. Zhang et al.16 considered chord error and feedrate, which enhanced efficiency as well as machining quality compared to point-to-point curvature optimization. Huang17 proposed a new curve, Airthoid, which represents curvature in a more concise way and uses this curve for local corner smoothing. Additionally, a time synchronization strategy that maximizes the acceleration process is established to improve machining efficiency.

In summary, numerical analysis methods are predominantly used in most recent research for local corner smoothing, and these methods are often applied only within or on the control polygon, leaving room for further optimization. In this paper, a new optimization approach is first established near the NURBS control polygon to smooth the local corner by formulating an optimization objective. Intelligent optimization algorithms are employed to solve it, and deep learning methods are utilized to accelerate the optimization process. The methods related to the intelligent optimization algorithms, deep learning models and their corresponding optimization functions, machining process simulation parameters, and comparative methods selected in this paper will be introduced in subsequent sections19,20,21,22,23,24.

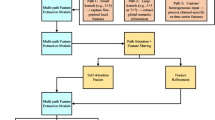

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: “The optimization architecture of the local tool path” introduces the optimization architecture of intelligent optimization (as shown on the left in Fig. 1). Section “Deep learning optimization” presents the deep learning model to accelerate the optimization process (as shown in the center of Fig. 1). To ensure processing quality, “Feedrate planning based on multiple constraints” discusses the relevant constraints (as shown on the right in Fig. 1). Section “Simulation results” describes simulations to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The optimization architecture of the local tool path

The curvature of the machining path has a significant effect on the feedrate. Various constraints, including geometric constraints, acceleration constraints, and contour error constraints, are converted from curvature to feedrate on the machining path. Therefore, it is essential to smooth the machining path at the geometry level.

NURBS

NURBS provide a generalized mathematical tool for free-form curves and have become one of the most common tools for describing machining paths in recent years. NURBS is shown in Eq. (1):

where \(P_{i}\) is the control point of the NURBS spline curve, \(w_{i}\) is the weight of the NURBS spline curve, and \(N_{i,p}\)(u) is the basis function of the NURBS spline curve. The basic functions of the NURBS splines are calculated through recursive calls, as shown in Eq. (2):

It is necessary to specify that “0/0 = 0” in Eq. (2). The first and second order derivatives of the basic functions of NUEBS spline curves are expressed in Eqs. (3) and (4):

and

Further, the first-order derivative and the second-order derivative of the NURBS curve can be expressed as:

The curvature of the NURBS curve can be expressed as:

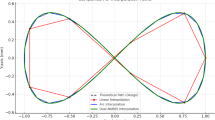

Each local corner that needs to be smoothed can be simplified into the form shown in Fig. 2b, which shows the distribution of NURBS spline control points using two different methods. In Fig. 2b, the blue circles within the black circle represent the additional control points compared to method 1. Since the curve is symmetric about the y-axis, an additional control point is added on the right side of the y-axis in the same way. The other NURBS control points, not circled in black, coincide with each other. The number of method 2 control points is 7, and the number of method 1 control points is 5. The NURBS splines generated by the two different methods are shown in Fig. 2a, and the curvature of the two spline curves is illustrated in Fig. 2c. It can be observed that the spline obtained by distributing the NURBS control points using method 2 exhibits a significantly greater reduction in curvature compared to method 1. Therefore, this paper primarily focuses on method 2.

It should be noted that although method 2 makes the locally smoothed path closer to the central control point (as shown in Fig. 2a), the addition of two control points may cause δ1 (as shown in Fig. 3) at the local machining path that exceeds the user-defined maximum approximation error δmax compared to method 1. Typically, δ2 is greater than δ1, and it is required that δ2 is also less than the maximum approximation error δmax. The subsequent optimization process ensures that max (δ2, δ1) < δmax.

The optimization process description

The optimization process in this paper can be described as finding two symmetric NURBS control points Pi+3, Pi+4 in the pink region such that the curvature is optimal within the region. Simultaneously, the constraint max (δ2, δ1) < δlim must be satisfied. The optimal control point positions should be determined without exceeding the pink region, while also ensuring that they do not coincide with the boundary (the control points Pi+3 and Pi+4, as shown in Fig. 4, cannot coincide with Pi−1, Pi, and Pi+1.). To ensure that the maximum curvature in the optimization region occurs as much as possible within the region shown in Fig. 2a, it should be ensured that ∠ Pi−2Pi−1Pi+3 and ∠ Pi−1Pi+3Pi are both smaller than ∠ Pi+3PiPi+4.

In summary, the three essential components of optimization can be described as follows:

where \({\text{max}}\left( {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{N} {cur_{i} } } \right)\) is each local corner that needs to be smoothed, and \(cur_{{i,{\text{max}}}}\) is the maximum curvature of each local corner. If the curvature of a local corner is too large, the feedrate needs to be reduced to satisfy certain constraints. Therefore, in order to ensure machining efficiency, it is required that the curvature should be less than \(cur_{{i,{\text{max}}}}\). \(P_{i + 3,x}^{i}\) denotes the x-coordinate of the Pi+3 control point for the ith local corner requiring smoothing, as shown in Fig. 3. Similarly, \(P_{i + 3,y}^{i}\) represents the y-coordinate of the \(P_{i + 3}\) control point for the ith local corner requiring smoothing. In order to avoid δ2 exceeding δmax, the last constraint uses the form of solving an equation to limit δ2. Since the location of the NURBS main control point cannot be guaranteed, (the main control point is the control point that has the most influence on the point of the NURBS spline curve), it is necessary to discuss the above situation separately: when the main control point is \(P_{i}^{i}\), set wi to 1, and set \(w{}_{i + 3}\) and \(w{}_{i + 4}\) to equal values before solving. When the main control point is \(P_{i + 3}^{i}\) or \(P_{i + 4}^{i}\), set \(w{}_{i + 3}\) and \(w{}_{i + 4}\) to 1, and then solve for wi.

The selection of optimization algorithm

The Particle Swarm Algorithm (PSO)22 is a heuristic and intelligent optimization algorithm. It is particularly effective in addressing multi-dimensional nonlinear problems and has a strong global search capability. Therefore, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is selected as the optimization agent model. The update strategy of the PSO algorithm is as follows:

where \(c_{1}\) represents the weight of the particle's next step being influenced by its own experience, which accelerates the particle towards the individual’s best position. \(c_{2}\) signifies the weight of the particle's next step being influenced by the experience of other particles, accelerating the particle towards the global best position. \(c_{3}\) denotes the weight that reflects the contribution of the group's experience in relation to the particle's own experience. The positions of the two additional control points (Pi+3 and Pi+3) in Fig. 4 are treated as particles to be optimized. Under the constraints of Eq. (7), the positions of the particles are iteratively updated within the feasible domain until the algorithm converges. The NURBS control point positions and the corresponding NURBS weights are stored as datasets for subsequent deep learning training.

Deep learning optimization

Intelligent optimization algorithms are affected by the population size, the search space, and the computational resources, which can lead to inefficient optimization. Deep learning, because of its efficient feature extraction capabilities and powerful autonomous learning efficiency, has made significant progress in applications. Deep learning relies on feature transformation between network layers and layer-by-layer training mechanisms to significantly improve the efficiency of complex data and special tasks. The Resnet23 architecture defines the desired underlying mapping as H(x) and modifies the stacked nonlinear layers to fit another mapping, f(x) = H(x) − x. The original mapping is then reformulated as f(x) + x. The expression f(x) + x can be effectively utilized through “shortcut connection” to prevent the vanishing gradient, which often leads to poor model training performance as the depth of deep learning layers increases, The network structure is shown in Fig. 5.

The selection of a loss function

In this paper, the Double- Resnet local corner smoothing algorithm is employed, including FDLS (First-Double-ResNet local smoothing algorithm) and SDLS (Second-Double-ResNet local smoothing algorithm). The above two algorithms are respectively used to predict the control point positions and the weight w of the NURBS curve. The overall structure of the FDLS is shown in Fig. 6. The FDLN inputs are the five NURBS spline control points before smoothing (as shown in Fig. 6 (1)), and its outputs are the two control points added after smoothing (as shown in Fig. 6 (2)). The input of the SDLS consists of all control points after smoothing (as shown in Fig. 6 (3)), and the output is the weights (as shown in Fig. 6 (4)) obtained by solving the equations that prevent the error δ2 from being excessively large under the last constraint.

The residual block is shown in Fig. 7, which performs a shortcut connection every 8 layers, and the whole structure has 64 fully connected layers, with dropout interspersed among them to prevent overfitting. The dropout is to reduce co-adaptation among neurons. Specifically, it prevents certain neurons from becoming overly reliant on others. Dropout enables the network to better adapt to varying input data by decreasing the dependencies between neurons.

The selection of a loss function and the selection of optimization algorithm

In deep learning, a loss function is needed to evaluate how good the model is. Since the task is a typical regression task, the MSE (Mean Squared Error) loss function is selected.

where s denotes the number of samples, which is the total count of data points in the dataset. \(y_{i}\) is the true value of the i-th sample. \(\widehat{y}_{i}\) is the predicted value for the i-th sample.

Since the optimization process of finding the optimal NURBS control points to achieve the optimal curvature will have high nonlinearity, this paper adopts the optimization algorithm Adam. The algorithm improves the global search capability and accelerates the convergence speed. Its optimization process can be expressed as follows24:

where \(m_{t}\) and \(v_{t}\) denote the first-order and second-order matrices of the gradient in momentum form at time t, respectively. \(\mathop {m_{t} }\limits^{ \wedge }\) represents the bias-corrected momentum first-order matrix, and \(\mathop {v_{t} }\limits^{ \wedge }\) denotes the bias-corrected momentum second-order matrix. \(\beta_{1}\) and \(\beta_{2}\) indicate the exponential decay rate of the first-order moment estimation and the exponential decay rate of the second-order moment estimation, respectively. Moreover, \(\beta_{1}^{t}\) and \(\beta_{2}^{t}\) refer to the t-th power of \(\beta_{1}\) and \(\beta_{2}\), respectively. \(\varepsilon\) denotes a constant close to 0 and is designed to ensure the stability of the numeric.

After extensive experiments, the settings for FDLS and SDLS in this paper are as follows: FDLS: batch size = 16, learning rate = 0.005; SDLS: batch size = 64, learning rate = 0.001. The training process is illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9. FDLS achieves a final convergence magnitude of 10−4 after 1000 iterations, while SDLS reaches a final convergence magnitude of 10−2 after 10,000 iterations. Both models reach the expected error magnitudes well before the maximum preset number of iterations. The FDLS model approaches convergence after around 2000 iterations. The SDLS model nears convergence after approximately 15,000 iterations. Neither appears overfitting. The detailed results of the training process can be found in ESM Appendix A.

Feedrate planning based on multiple constraints

The geometric error and the contour error

The chord error can be calculated by Eq. (15):

where \(\rho\) represents the radius of curvature, \(T\) denotes the interpolation period. Consequently, the feedrate constrained by the chord error can be determined:

The relationship between contour error and feed rate can be expressed as Eq. (17):

where \(\varepsilon_{\lim }\) is the contour-error limitation, \(\zeta\) is Damping ratio, \(w_{n} = \sqrt {K_{p} /J}\), \(\zeta = B/(2\sqrt {JK_{p} } )\), \(w_{n}\) is undamped natural frequency, Kp is the position-loop proportional gain, J is the equivalent rotational inertia of the feed-drive system, and B is the equivalent damping factor.

The feedrate constrained by normal acceleration and normal jerk

When the feedrate is v, the normal acceleration can be derived from Eq. (18)19:

Therefore, the feedrate under the normal acceleration constraint is described as follows:

where \(a_{n,\lim }\) is the limit of the normal acceleration.

The jerk can be expressed by the rate of change of acceleration as shown in Fig. 10:

The relationship between the jerk limit and the radius of curvature can be expressed as:

where \(j_{n,\lim }\) is the limit of the jerk.

Based on the above constraints, the feedrate at each point on the NURBS spline can be determined:

where \(v_{f}\) is the maximum feedrate for each point.

The feed rate planning method adopts the method described in reference19. The NURBS machining path is discretized into a finite number of sample points. The curvature is converted to feed speed based on Eq. (22). The point less than the maximum feedrate is defined as the sensitive interval point. The minimum speed within the sensitive interval is defined as the feedrate of the sensitive interval. Set the points greater than or equal to the maximum feedrate to the maximum feedrate and define them as non-sensitive intervals. Since the feedrate changes continuously during the machining process, acceleration and deceleration should be performed in the non-sensitive intervals to smoothly reach the feedrate for each sensitive interval. Considering the limited drive capabilities of each axis, certain sensitive interval speeds need to be updated to ensure that acceleration and deceleration can be completed within the non-sensitive intervals. The parameters are set as shown in Table 1.

Simulation results

In this section, three simulations are performed to verify the effectiveness of the proposed methods. Example 1 is introduced in this paper to demonstrate that the proposed method can indeed optimize the machining path in terms of curvature. Example 2 and Example 3 are presented to show that the proposed method, compared to other methods20,21, is more applicable to paths with both large and small curvatures (as in Example 2), as well as paths with a higher frequency of large curvature segments that are close each other (as in Example 3). To further verify the generality and optimization efficiency of the proposed deep learning model, the comparative data between PSO algorithm and the proposed deep learning model can be found in ESM Appendix B.

Case 1

Case 1 selects the W-shaped machining path shown in Fig. 11. As indicated in Table 2 and Fig. 12a, the approximation error in each local corner did not exceed the maximum local approximation error. Additionally, the curvature after optimization decreased to varying degrees compared to before optimization, with a maximum reduction of up to 92.7%. The above results demonstrate that the proposed method can optimize the curvature of each local corner while maintaining the shape of the machining path to a certain extent. After optimizing the curvature, the tool tip can pass through the local corners at a higher federate (as shown in Fig. 12b). Due to the large curvature of the local corners and the shortness of the arc lengths of the neighbor corner, the feedrate is low (as shown in Fig. 12b). It can be observed that none of the processing parameters exceeds the limit values (guaranteeing machining quality) through Fig. 12c–h, proving that the constraints proposed in this paper are effective.

Case 2

The “Dress” machining path is selected as case 2, which is characterized by both large and small curvatures. Due to the short arc length left for acceleration and deceleration, neither the methods proposed in references20,21 nor the method presented in this paper were able to reach the maximum feedrate vp. The feedrate distributions of the three methods are shown in Fig. 13a. It can be seen by the processing time shown in Fig. 13b that the method proposed in this paper achieved the shortest machining time, followed by the method in Ref.20, while the method in reference21 resulted in the longest machining time. The proposed method reduced machining time by 8% and 36.9% compared to the methods in Refs.20,21, respectively. Although the maximum values of chord error, normal acceleration, normal jerk, contour error, tangential acceleration and tangential jerk of the method proposed in this paper are still larger (e.g., Fig. 13c–h), they are all smaller than the limit values, which proves that the aforementioned constraints are effective. The approximation error for case 2 is shown in Fig. 13i. It should be noted that the machining path in case 2 has symmetric geometry. Therefore, only the approximation error for each local corner in half of the symmetric structure is shown. The approximation error at each local corner for all three methods is less than the maximum value 0.1 mm.

Case 3

In case 3, the “torch” machining path shape is selected as shown in Fig. 14a, and the local corner of the path with large curvature is close to each other. The overall value of the path curvature is larger, so the feedrate is lower than in case 2. Given that the path's beginning and ending portions are made up of arcs with a curvature of 0 and comparatively lengthy arc lengths, the feedrate can be accelerated to the maximum feedrate vp, as shown in Fig. 14b. It also can be observed that the proposed method results in relatively high values for chord error, normal acceleration, normal jerk, contour error, tangential acceleration and tangential jerk (e.g., Fig. 14c–h), but none of these exceed the limit value. It is clear from Fig. 14i that the method proposed in this paper achieves smaller approximation errors compared to Refs.21,22, indicating that our deep learning approach offers better optimization for machining paths with multiple closely spaced high-curvature features. Based on the analysis of case 2 and case 3, it can be seen that the proposed method not only ensures the accuracy of the machining process but also optimizes curvature to a certain extent. It improves processing efficiency while maintaining processing quality and meeting the specified constraints.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a novel method that transforms the local corner smoothing problem into an optimization problem. The optimization objective, design variables, and constraints are defined, and the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is employed to solve it. Considering the impact of population size and computational resources on intelligent optimization algorithms, the deep learning method is employed to establish the mapping between inputs and outputs to improve optimization efficiency. The deep learning network FDLS is used to optimize the positions of NURBS control points, while the network SDLS is utilized to optimize NURBS weights. To ensure processing quality, this paper considers chord error, normal acceleration, normal jerk, and contour error as constraints for limiting the federate. Finally, it is demonstrated through the cases that the proposed method can improve processing efficiency while maintaining processing quality. The future research is to extend the method to 5-axis CNC machining.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.Data and materials will be available upon reasonable requests. If someone wants to request the data from this study, please contact Xiao-yan Teng (E-mail: tengxiaoyan@hrbeu.edu.cn).

References

Li, B. et al. Trajectory smoothing method using reinforcement learning for computer numerical control machine tools [J]. Robot. Computer-Integr. Manufact. 61, 101847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2019.101847 (2020).

Song, D. N. et al. Global smoothing of short line segment toolpaths by control-point-assigning-based geometric smoothing and FIR filtering-based motion smoothing [J]. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 160, 107908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.107908 (2021).

Tajima, S. & Sencer, B. Global tool-path smoothing for CNC machine tools with uninterrupted acceleration [J]. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 121, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2017.03.002 (2017).

Lu, T. C. & Chen, S. L. Real-time local optimal Bézier corner smoothing for CNC machine tools [J]. IEEE Access 9, 152718–152727. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3123329 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. (B.6) Corner trajectory smoothing with asymmetrical transition profile for CNC machine tools [J]. Int. J. Machine Tools Manufacture. 144, 103423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2019.103492 (2019).

Xu, F. & Sun, Y. A circumscribed corner rounding method based on double cubic B-splines for a five-axis linear tool path [J]. Int. J. Adv. Manufacturing Technol. 94, 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-0869-x (2018).

Huang, J., Du, X. & Zhu, L. M. Real-time local smoothing for five-axis linear toolpath considering smoothing error constraints [J]. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 124, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2017.10.001 (2018).

Hu, Q. et al. An analytical C 3 continuous local corner smoothing algorithm for four-axis computer numerical control machine tools [J]. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 140(5), 051004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4039116 (2018).

Hu, Y. et al. Enhancing five-axis CNC toolpath smoothing: Overlap elimination with asymmetrical B-splines [J]. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 52, 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2024.05.013 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Local asymmetrical corner trajectory smoothing with bidirectional planning and adjusting algorithm for CNC machining [J]. Robot. Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 68, 102058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2020.102058 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. Asymmetrical pythagorean-hodograph spline-based C4 continuous local corner smoothing method with jerk-continuous feedrate scheduling along linear toolpath [J]. Int. J. Adv. Manufacturing Technol. 121(9), 5731–5754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-09463-y (2022).

Wan, M. & Qin, X. B. Asymmetrical pythagorean-hodograph (PH) spline-based C3 continuous corner smoothing algorithm for five-axis tool paths with short segments [J]. J. Manuf. Process. 64, 1387–1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.02.059 (2021).

Peng, J. et al. An analytical method for decoupled local smoothing of linear paths in industrial robots [J]. Robot. Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 72, 102193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2021.102193 (2021).

Lei, C. et al. Local tool path smoothing based on symmetrical NURBS transition curve with look ahead optimal method: Experimental and analytical study [J]. Int. J. Adv. Manufacturing Technol. 126(3), 1509–1526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-10861-z (2023).

Han, J. et al. A local smoothing interpolation method for short line segments to realize continuous motion of tool axis acceleration [J]. Int. J. Adv. Manufacturing Technol. 95, 1729–1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-1264-3 (2018).

Chen, Y., Huang, P. & Ding, Y. An analytical method for corner smoothing of five-axis linear paths using the conformal geometric algebra [J]. Comput. Aided Des. 153, 103408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cad.2022.103408 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. A novel local smoothing method for five-axis machining with time-synchronization feedrate scheduling [J]. IEEE Access 8, 89185–89204. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2992022 (2020).

Sencer, B., Ishizaki, K. & Shamoto, E. A curvature optimal sharp corner smoothing algorithm for high-speed feed motion generation of NC systems along linear tool paths [J]. Int. J. Adv. Manufacturing Technol. 76, 1977–1992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-6386-2 (2015).

Jia, Z. et al. A NURBS interpolator with constant speed at feedrate-sensitive regions under drive and contour-error constraints [J]. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 116, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2016.12.007 (2017).

Zhang, L., Zhang, K. & Yan, Y. Local corner smoothing transition algorithm based on double cubic NURBS for five-axis linear tool path [J]. J. Mech. Eng./Strojniški Vestnik. https://doi.org/10.5545/sv-jme.2016.3525 (2016).

Yang, J. & Yuen, A. An analytical local corner smoothing algorithm for five-axis CNC machining [J]. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 123, 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2017.07.007 (2017).

Kennedy, J., Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization [C]. in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, Vol 4, pp 1942–1948. (IEEE, 1995). https://doi.org/10.1109/MHS.1995.494215.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition[C]. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

Zhou, Y. et al. A randomized block-coordinate adam online learning optimization algorithm[J]. Neural Comput. Appl. 32(16), 12671–12684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-04718-9 (2020).

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 32472000) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 3072024GH0701.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, investigation, verification tests, formal analysis, writing – original draft: Bai Jiang. Conceptualization, methodology, writing – reviewing, supervision: Xiao-yan Teng, Bing Li. Resources, supervision, validation: Rong Sun, Ze-long Li, Liang Xu ,Huang Liao.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This chapter does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable. The article involves no studies on humans.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, B., Sun, R., Li, Zl. et al. Local corner smoothing based on deep learning for CNC machine tools. Sci Rep 15, 404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84577-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84577-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Recent Advances in CNC Technology: Toward Autonomous and Sustainable Manufacturing

International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing (2025)