Abstract

Aftershocks can cause additional damage or even lead to the collapse of structures already weakened by a mainshock. Scarcity of in-situ recorded aftershock accelerograms heightens the need to develop synthetic aftershock ground motions. These synthesized motions are crucial for assessing the cumulative seismic demand on structures subjected to mainshock-aftershock sequences. However, existing research consistently highlights the challenge of accurately representing the spectral differences and interdependencies between mainshock and aftershock ground motions. In this study, we propose an innovative approach utilizing automated machine learning (AutoML) to forecast the acceleration spectrum (Sa) at varying periods for the largest expected aftershock. The AutoML model integrates essential parameters derived from the mainshock, including its Sa, and rupture parameters (moment magnitude, source-to-site distance), and site information (average shear-wave velocity in the top 30 m). Subsequently, we employ a wavelet-based technique to generate synthetic aftershock accelerograms that align with the spectrum of the mainshock, using the mainshock ground motion as a reference input. In contrast to classical machine learning techniques, AutoML requires minimal human involvement in model design, selection, and algorithm tuning. We collected 2500 sets of mainshock and in-situ aftershock recordings from a global database to train the AutoML model. Notably, even without aftershock rupture parameters as inputs, our predicted Sa shows significant agreement with actual recorded aftershock ground motions. Our predictions achieved R2 scores ranging from 0.85 to 0.9 across various periods, affirming the model’s accuracy. Furthermore, the Pearson correlation between predicted Sa intensities across different periods closely mirror that derived from observed aftershock recordings. These findings validate our trained AutoML model’s capability to forecast the response spectrum of the largest expected aftershock ground motions. The peak ductility demand of SDOF systems, using artificial mainshock-aftershock ground motions as input, also shows good agreement with those under recorded seismic sequences. Given the fully automated nature of our approach, the AutoML framework could be extended to predict other relevant non-Sa intensity measures of aftershocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strong earthquakes are often followed by multiple aftershocks within a relatively short time interval1,2. A structure that has already been damaged during the preceding mainshock typically cannot be effectively repaired within a short time. Consequently, it is prone to experiencing significant additional damage from subsequent aftershocks3,4,5,6,7. In recent years, numerous studies have been conducted to examine the structural nonlinear responses8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 when subjected to mainshock-aftershock sequences. These investigations have revealed that aftershocks can have detrimental impacts on a structure’s seismic performance, rendering mainshock-damaged structures more vulnerable.

Evaluating structural safety under mainshock-aftershock sequences is challenging due to the insufficient availability of recorded aftershock data and limited access to these recordings. Goda and Taylor16 claimed that an incomplete database of real mainshock-aftershock sequences may result in the underestimation of the aftershock impact. In engineering practice, aftershock ground motions are often generated by repeating or scaling the recordings of the corresponding mainshocks, disregarding the potential differences in spectrum shape between mainshock and aftershock events17,18. This approach has been validated to significantly overestimate the inelastic structural seismic demand16. In addition, in-situ mainshock and aftershock ground motions tend to share features due to similar source characteristics and wave propagation path factors. Therefore, it is crucial to estimate the response spectrum of aftershocks by considering the dependency of aftershock ground motion characteristics on the mainshock event. Failing to do so could introduce further bias in the assessment of structural vulnerability under mainshock-aftershock sequences19,20,21.

Several methods have been developed to predict or generate aftershock acceleration spectra, including ground motion model (GMM)-based methods, mainshock-consistent scaling methods, and machine learning-based methods.

The GMM-based method is considered indirect because the spectral accelerations (Sa) of aftershocks are not directly derived from the Sa of the corresponding mainshocks. In this approach, the occurrence time and seismic parameters (i.e., magnitude, distance, and other rupture parameters) of the aftershock event must first be estimated. For instance, Goda and Taylor17 determined the magnitude of aftershock events using a combination of the generalized Omori’s law, Gutenberg–Richter’s law22, Bath’s law23, and the modified Omori’s law24. Similarly, Hu et al.25 generated magnitudes, locations, and occurrence times of aftershock sequences using the branching aftershock sequence (BASS26) seismicity model. Once the aftershock event catalog is established, the Sa intensities of aftershocks can be predicted using ground motion models (GMMs), as demonstrated in studies such as [27–29]. The GMM-based method requires detailed seismicity information of the studied region. However, mature GMMs for aftershock events are still limited; most existing GMMs are only applicable to mainshock events. Consequently, the direct application of these GMMs may not accurately reflect the dependency of aftershock spectral characteristics on the mainshock event.

The mainshock-consistent scaling method proposed by Papadopoulos et al.21 is referred to as a conditional method because the aftershock Sa shape is predicted based on the corresponding mainshock response spectrum. In recent years, the dependence between the response spectral shapes of mainshocks and aftershocks has been investigated by many scholars28,29, and several models have been proposed to describe their joint distributions28,29,30. Based on the joint distribution of the spectral epsilons of mainshock-aftershock pairs (i.e., the indicator of spectral shape31), the conditional mean and standard deviation of the spectrum for aftershock ground motions can be predicted. The conditional method relies heavily on the sufficiency and efficiency of the established correlation relationships between Sa ordinates. The utilized empirical correlation relationship between Sa significantly influences the generated aftershock response spectrum results.

In recent years, machine learning techniques have been used to predict aftershock spectra because ML-based methods do not rely on predefined empirical joint distribution models or relationships between the Sa of mainshocks and aftershocks. For instance, Vahedian et al.32 developed an artificial neural network (ANN)-based prediction model for aftershock spectra using the Sa of corresponding mainshocks as inputs. Moreover, Ding et al.33 applied deep neural networks (DNN) and conditional generative adversarial networks to predict spectral accelerations of aftershock ground motions using eight seismic variables and the spectral accelerations of mainshocks as input. Although ML-based methods provide a promising way to estimate the response spectrum of aftershock events, previous studies utilized a relatively limited number of real mainshock and aftershock recordings as the training database. This limitation affects the reliability and generalization ability of the developed ML-based prediction models. Specifically, only 126 sets of mainshock-aftershock sequences recorded on soil type C were used in Vahedian et al.32, and 503 sets of mainshock-aftershock sequences were adopted in Ding et al.33 to predict aftershock Sa ordinates at more than 20 periods. This dataset size is not large enough to fully exploit the power of deep learning techniques. Additionally, traditional deep learning methods often require high computational costs to search for optimal hyperparameters34. This makes it inconvenient to update the ML-based prediction model of aftershock response spectra when new training datasets are added. Therefore, we decided to utilize automated machine learning (AutoML) techniques to automatically select and compose machine learning models. The basic idea of AutoML is to, given a training dataset and an error measure, utilize minimal misfit to automate the search for the optimal learner and hyperparameters34.

Two folds of efforts are taken in this study. First, a total of 2500 sets of mainshock-aftershock sequence recordings are selected from worldwide database and used as training and test datasets. This dataset is significantly larger than previous ML-based studies32,33. Based on our extended training dataset, FLAML Fast and Lightweight AutoML Library34 (FLAML)is used to train the prediction model of aftershock Sa intensities. The predicted aftershock acceleration spectrum is then used to generate artificial aftershock ground motions using wavelet-based method. The inelastic seismic demand of single degree of freedom (SDOF) system under generated artificial mainshock-aftershock sequences is compared with that under real seismic sequences.

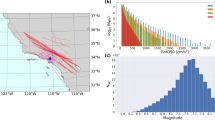

Training/Testing dataset

A relatively large database of mainshock-aftershock sequences has been established, comprising a total of 2,500 mainshock recordings with their corresponding aftershock ground motions. In this database, the two horizontal components of ground motion recordings are treated as two independent training samples. Of the 2,500 sets of mainshock-aftershock recordings, 1,112 sets and 1,314 sets are selected from the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER) NGA-West2 database35 and K-NET/KiK-net36 in Japan, respectively, with the remaining 74 sets selected from the ITACA database37 (refer to the electronic supplement for details). It is noteworthy that only mainshock events with a magnitude of Mw > 5.0 are considered in this study. The corresponding aftershock sequence is identified from earthquake clusters using the time window and distance range suggested by Gardner and Knopoff38. In the aftershock sequence following a given mainshock event, only the aftershock event with the largest magnitude is considered, as it tends to cause significant additional damage to structures already compromised by the mainshock[40–42]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the stations triggered by both the mainshock and the largest aftershock are distributed across various regions, including Japan, Taiwan, Europe (mainly the Mediterranean coast), Turkey, and the western United States.

Spatial distribution epicenter locations for mainshock event and corresponding aftershock event with largest magnitude. The trigged stations are distributed in three regions: (a) Japan and China Taiwan island, (b) European (mainly mediterranean coast) and Turkey, and (c) western United States. The figure is plotted using GMT6 (generic mapping tools) software (https://doi.org/10.1029/98EO00426).

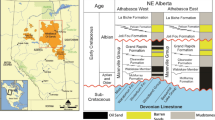

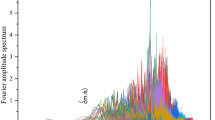

Figure 2 shows the distributions of moment magnitude (Mw) and hypocenter distance for the selected mainshock-aftershock ground motions. All recordings are randomly divided into 80% for training and 20% for testing. It should be noticed that the two horizontal components from the same event were not split between the training and test sets. The train and test set contains data from entirely distinct events to maintain strict separation between training and testing procedure. The histograms in Fig. 2 demonstrate that the sample size proportions of different magnitude and distance bins are similar between the training and testing datasets. This is crucial for controlling the potential overfitting of our ML-based model. To examine the spectral content of the selected recordings, Sa values of the mainshock recordings and the associated largest aftershock recordings are compared at various periods, as shown in Fig. 3. Notably, the Sa values of the aftershock recordings are generally lower than those of the mainshock recordings, and the decay tendency of the spectral shape in the long period range also differs. This observation underscores that simply scaling the mainshock spectrum to represent the aftershock spectrum neglects the potential differences in spectral shape, highlighting the importance of accurately predicting Sa values for aftershocks.

Distribution of moment magnitude with respect to hypocenter distance regarding (a) mainshock recordings and (b) aftershock recordings. Training dataset and testing dataset are represented with different colors. Histograms of magnitude and distance bins regarding training and testing dataset are also compared in the figure.

Utilized AutoML architecture

In this section, we briefly review the concept and technical advancements of FLAML (Fast and Lightweight AutoML Library)[35] and compare it to other AutoML platforms. We then introduce the architecture and main components of FLAML.

In most AutoML systems, conducting a large number of trials in an extensive search space is common practice. Consequently, the order of the trials significantly impacts the efficiency of the search process. Meta-learning is a commonly used technique to improve search order, based on the assumption that a large number of datasets and experiments can be collected for meta-training, allowing the performance of learners and hyperparameters to be measured accordingly. This requires conventional AutoML systems to have much more training data to find an optimal prediction model. However, in our case, the mainshock-aftershock datasets are limited and not suitable for meta-learning in AutoML.

Machine learning comprises various algorithms, including K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Gaussian Process (GP). Traditionally, the choice of algorithm depends on the specific application and the unique characteristics of each method. In this study, ensemble learning, which integrates multiple algorithms, is introduced in the automated machine learning framework. The ensemble techniques used in this research are Random Forest (RF), Extremely Randomized Trees (ET), AdaBoost (AB), and Gradient Boosting (GB).

FLAML is designed to robustly adapt to an ad-hoc dataset out of the box and does not require users to collect a large number of diverse meta-training datasets as preparation. After customizing the learners, search spaces, and optimization metrics, FLAML can be directly used to solve the problem without the need for an additional costly round of meta-learning. For further application and debugging, a single learner trained by FLAML, rather than ensembles used in other AutoML systems, is unquestionably better suited to our problem. The architecture of the FLAML model utilized is presented in Fig. 434. It consists of two layers: an ML layer and an AutoML layer. The ML layer contains multiple candidate learners that are fed to the AutoML layer. The AutoML layer comprises a learner proposer, a hyperparameter and sample size proposer, a resampling strategy proposer, and a controller.

As labeled in Fig. 4, computation process in FLAML could be divided into four main steps, where the first three steps focus on choosing variables in each component, including the leaner, resampling strategy and hyperparameters. In Step 4, the controller will invoke the trial using selected learner in ML layer, and validate the error metrics and cost. Steps 2–4 are repeated by iterations until running out of budget or reaching threshold of error. Next we briefly introduce basic idea of each step in FLAML.

Step 1 Resampling strategy proposer chooses r.

Resampling strategy is decided based on a simple thresholding rule. If the training dataset has fewer than 100 K instances and the budget is smaller than 10 M per hour, we usually use cross validation. In our case, the five-fold cross-validation is selected in this step. This simple thresholding rule can be easily replaced by more complex rules, e.g., from Meta learning.

Step 2 Learner proposer choosesl.

The notion of estimated cost for improvement (ECI) is used in the search strategies34, which is defined in Eq. (1). The estimated cost of improvement for learner l, i.e., ECI(l), is defined as the cost of searching configurations in l that result in lower error (denoted as \({\tilde {\varepsilon }_l}\)) than the current best error among all learners. The estimated cost for improvement is defined as Eq. (1). K0 (abbreviations of K0 (l)) is the total cost spent on l so far, and δ (abbreviations of δ(l)) be the error reduction between the two configurations.

Each learner l is chosen with probability in proportion to 1/ECI(l). The random sampling according to ECI in Step 2 and the random restarting in Step 3 help method escape from local optima. The ECI-based prioritization in Step 2 favors cheap learners in the beginning but penalizes them later if the error improvement is slow.

Step 3 Hyperparameter and sample size proposer choosesh and s.

The random direct searching strategy proposed by Wu et al.43 is utilized in this step to perform cost-effective optimization for cost-related hyperparameters. A random direction is utilized to train a model at each iteration. If error is not decreased, another model is trained in another direction. The training sample size is small at start of search process, and gradually approaches the size of complete dataset as the search progresses. This search process will end when the error fails to converge. The hyperparameter and sample size proposer in Step 3 tends to propose cheap configurations at the starting of the search process. However it quickly moves to the configurations with high model complexity and large sample size in the later stage of the search process.

Step 4 Validation of the error and cost metrics.

After a round of ECI-based sampling, randomized direct search, and updating of ECIs, the controller will invoke the trial using selected learner in ML layer and measure the corresponding validation error and cost. Then a new round of trail will start until running out of budget or reaching threshold of error.

The designs mentioned in Steps 1 ~ 4 enable FLAML to efficiently navigate large search spaces for both small and large datasets. The complexity of algorithm is linearly related to the dimensions of the hyperparameters rather than the number of trails. Therefore the computation cost in AutoML layer is negligible comparing with the cost spent in ML layer.

Prediction model of S a for aftershock ground motions

For the AutoML-based prediction model in our study, input and output variables are listed as follows:

-

Input variables: mainshock moment magnitude; hypocenter distance; average shear-wave velocity in the top 30 m (Vs30); mainshock Sa at the interested periods;

-

Output variables: largest expected aftershock Sa at interested periods;

Faulting mechanism is another possible input feature that may impact spectral prediction results. Approximately 45% of the recordings in the training and test sets come from the NGA-West2 database. When solely using the NGA-West2 database with detailed fault mechanism information for training and testing, we found no significant improvement when including the fault mechanism as an input variable. Additionally, reliable geometric information of the rupture plane is hard to determine for ground motion events in K-NET, KiK-net and ITACA. Therefore, we decided to use only magnitude, hypocenter distance, and VS30 as input variables.

To validate the performance of utilized AutoML model on Sa at different periods, 21 specific vibration periods (T) ranging 0.0 s to 4.0 s are selected: {T = 0s; 0.1s; 0.12s; 0.15s; 0.18s; 0.22s 0.26s 0.32s; 0.39s; 0.47s; 0.57s; 0.7s; 0.85s; 1.03s; 1.25s; 1.52s; 1.84s; 2.23s; 2.71s; 3.29s; 4.0s}. All the input/output variables are not normalized.

We applied FLAML to train the model on an AMD Ryzen 9 5900HX CPU, and the training process took nearly 100 s. After establishing the prediction model of Sa for aftershock ground motions, its performance was evaluated using the testing dataset. To do this, the predicted Sa ordinates of aftershocks at a total of 21 specific vibration periods were compared with the measured values, as shown in Fig. 5. The predicted Sa values of aftershocks are generally close to the measured results. To further validate this result, the R2 score, a commonly used performance measurement for ML models, was calculated and is shown in Fig. 5. The R2 score is defined as:

where\({y_i}^{{{\text{observe}}}}\)and\({y_i}^{{{\text{predict}}}}\)are the measured and predicted Sa values of aftershocks, respectively; and\(\overline {y}\)is mean value of observations. As shown in Fig. 6, the calculated R2 scores for Sa intensities of aftershocks at different periods range from 0.85 to 0.93. This result indicates that the trained model has a good agreement with the measured Sa values, consolidating the strong performance of the developed prediction model.

The Sa values of random selected samples in the testing dataset are compared with observations in Fig. 7. We compare one of the GMM-based method with AutoML-based model. The basic idea of conditional mean spectrum for aftershock (CMSA) was proposed by Zhu et al[29], the conditional mean epsilons of aftershocks are computed based on the corresponding values of mainshocks using the correlation relationship among them, and then these conditional mean epsilons are further used to modify the predicted response spectra of aftershocks estimated by a specific GMM. This method considers the dependence of the spectral shapes (epsilons) between mainshocks and aftershocks. The aftershock information (e.g. magnitude, distance) are required as input for GMM to generate the spectrum, which is also compared. From Fig. 7, it can be observed that although the CMSA requires aftershock magnitude and distance as inputs, the regional nature of the Ground Motion Model (GMM) limits its ability to accurately represent seismic characteristics across different region. Consequently, biases in the bakcbone response spectrum are propagated to the subsequently generated CMSA, leading to significant deviations in certain periods. In contrast, the AutoML-based method, which does not rely on aftershock magnitude and distance, produces response spectra that are largely closer to the target spectral shape, demonstrating the effectiveness of the developed AutoML-based model.

For further validation of the predicted Sa values of aftershocks, the correlations between the predicted aftershock Sa values at different periods are compared with those between real aftershock Sa values at different periods, as shown in Fig. 8. In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient is used to measure the correlation between the Sa values at different periods, which is defined as:

where Sai(T1) and Sai(T2) are predicted (or real) spectral values at T1 and T2, respectively; and \(\mathop {Sa({T_{\text{1}}})}\limits^{{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}\)and\(\mathop {Sa({T_2})}\limits^{{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}\) are predicted (or real) mean spectral values at T1 and T2, respectively. The correlation coefficient structure between the predicted Sa at different periods are close to the observations in testing dataset. The good agreement validates that the prediction model successfully capture spectral characteristic of largest expected aftershock.

In many applications, understanding why a ML model makes a particular prediction is just as important as the prediction’s accuracy. However, ML-based models are often very complex and make the interpretation work difficult. This study used a unified framework, i.e., SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), to obtain a better understanding of the predictions by AutoML-based model described earlier50. The importance of input variables in every sample is measured by the Shapley values. It is calculated as mean value of the absolute Shapley values regarding the entire dataset. Specifically, Tree SHAP is chosen in our work to estimate the Shapley values. It can be seen from Fig. 9 that Sa intensity levels of mainshocks show more significant influence on final prediction results, comparing with other input variables. The average of Shapley values for mainshock Sa is almost five times larger than the earthquake magnitude, distance and Vs30.

Shapley values can also be used to describe the feature dependency of various input variables. The scatter plots in Fig. 10 illustrate the relationship between features (or input variables) and Shapley values. The color of the dots represents the values of another potentially critical feature, with blue to red indicating small to large values. The Shapley value is measured with increasing levels of Sa intensities of mainshocks. As expected, the amplitude of Sa is generally related to the magnitude of the mainshock event. The resulting large Shapley values indicate that moderate to large mainshock events with high Sa values tend to have a greater impact on our final prediction results than smaller mainshock events. However, no clear trend is observed between mainshock event magnitude and Shapley value. This demonstrates that using magnitude as the sole input variable does not achieve accurate prediction results. Furthermore, the Shapley values tend to decrease with increasing hypocenter distance and VS30 values. This suggests that soil sites (with VS30 less than 760 m/s) and non-far-field recordings contribute more to the prediction performance. Given that magnitude, distance, and VS30 are all independent variables, no relationship between these features is expected.

Assessment of peak ductility demand

For a given mainshock event, the Sa coordinates of aftershocks can be predicted using our trained AutoML-based model. Subsequently, the wavelet-based spectrum-compatible ground motion generation method of Hancock et al.45 is utilized to simulate aftershock ground motions, with the corresponding mainshock as the seed recordings. In this section, SDOF systems are used for illustration, and the structural inelastic response under real and artificial mainshock-aftershock sequence recordings is compared. Similar to the work of Goda and Taylor16, a time interval of 60 s is inserted between the mainshock and aftershock recordings to ensure that the mainshock-induced structural vibration ceases gradually before the occurrence of the subsequent aftershock.

The existing hysteresis models can be generally categorized into two groups: polygonal hysteresis models and smooth hysteresis models. As stated by Ning et al.50, the smooth hysteretic model performed much better than the polygonal one for both pinched and non-pinched hysteresis behaviors. Among the available smooth hysteretic models, the inelastic restoring force translational displacement relationship predicted by the BWBN model matched well with the experimental data, with an average error of 3%50. In this study, the Bouc-Wen model, which accounts for both pinching and degradation effects, is used to simulate the nonlinear behaviors of SDOF systems. The specific values of the model’s parameters can be found in [16] and [52].

The peak ductility demands under real and artificial mainshock–aftershock sequences are compared. To ensure the rigor of the conclusions, we used the ground motion samples in the testing dataset for calculating the structural responses. The empirical cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves of the ductility demand under 500 mainshock-aftershock sequences are plotted in Fig. 11. For SDOF systems with different vibration periods (ranging from 0.2s to 1.0s) and different constant strength reduction factors (R = 2, 5), a good agreement is observed between the CDF results of real and artificial mainshock-aftershock sequences. This observation consolidates the reliability of the developed AutoML-based model for predicting Sa intensities of aftershock ground motions. Furthermore, this result also demonstrates the practical implementation potential of the proposed AutoML-based model.

Conclusions

An Automated Machine Learning (AutoML)-based model has been proposed to predict the Sa intensities of the largest expected aftershock, given the response spectrum and rupture/site parameters (including the event magnitude, hypocenter distance, and VS30) of the corresponding mainshock. A fast and lightweight AutoML library was used to automatically search for optimal ML-based prediction models. The training/testing dataset is significantly larger than that used in previous similar work employing deep learning techniques, comprising 2500 mainshock-aftershock sequences collected from a global ground motion database. The R2 score for different Sa ordinates at 21 vibration periods for the testing dataset (500 sets of recordings) ranged from 0.85 to 0.93, demonstrating the good performance of the prediction model. Additionally, the spectral correlation structure among the predicted Sa ordinates at different periods was consistent with that among the measured Sa ordinates of real aftershock events. This result indicates that our proposed AutoML-based prediction model successfully captures the spectral characteristics of the largest expected aftershocks.

SHAP analysis revealed that moderate to large mainshock events with high Sa values have a much greater influence on our final prediction results. As a practical application, the developed AutoML-based prediction model of aftershock Sa intensities was used to generate artificial aftershock accelerograms using a wavelet-based spectrum-compatible method, with the corresponding mainshock as seed recordings. The peak ductility demands of SDOF systems under artificial mainshock-aftershock sequences and recorded ones were compared and showed good agreement.

It is noteworthy that the performance of our AutoML-based models could be further improved with updated datasets without the need to repeatedly search for optimal hyperparameters or redesign prediction models. The utilized AutoML framework could also be extended to new tasks, such as predicting other non- Sa intensity measures of aftershocks. Although the AutoML technique is essentially a “black-box” that needs to be used with caution, it offers a promising approach to solving similar problems in earthquake engineering.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Mainshock and Aftershock recordings used in this study are collected from NGA-West2 database of PEER Ground Motion Database at https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu/; K-NET and KiK-net database at https://www.kyoshin.bosai.go.jp/; Italian Accelerometric Archive of waveform at https://itaca.mi.ingv.it/. The detailed information of selected mainshock and aftershock ground motions can be referred to the electronic supplement. The python script for training FLAML and example cases have been uploaded in Github: https://github.com/Wangmengcivil/Prediction-of-aftershock-spectral-acceleration-using-automated-machine-learning-AutoML.

References

Chi, W. C. & Doug, D. Crustal deformation in Taiwan: results from finite source inversions of six Mw> 5.8 chi-chi aftershocks. J. Phys. Res. 109, B07305 (2004).

Atzori, S. et al. The 2010–2011 Canterbury, New Zealand, seismic sequence: multiple source analysis from InSAR data and modeling. J. Phys. Res. 117, B08305 (2012).

Ruiz-Garcia, J. & Aguilar, J. D. Aftershock seismic assessment taking into account postmainshock residual drifts. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 44(9), 1391–1407 (2015).

Ghosh, J., Padgett, J. E. & Sánchez-Silva, M. Seismic damage Accumulation in Highway bridges in Earthquake-Prone regions. Earthq. Spectra. 31(1), 115–135 (2015).

Wen, W., Zhai, C. & Ji, D. Damage spectra of global crustal seismic sequences considering scaling issues of aftershock ground motions. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 47(10), 2076–2093 (2018).

Qiao, Y. M., Lu, D. G. & Yu, X. H. Shaking table tests of a Reinforced concrete frame subjected to mainshock-aftershock sequences. J. Earthquake Eng., 2020(5), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2020.1733710

Potter, S. H., Becker, J. S., Johnston, D. M. & Rossiter, K. P. An overview of the impacts of the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Int. J. DisasterRisk Reduct. 105, 6–14 (2015).

Goda, K. Nonlinear response potential of mainshock–aftershock sequences from Japanese earthquakes. Bull. Seismological Soc. Am. 102(5), 2139–2156 (2012).

Hatzigeorgiou, G. D. Ductility demand spectra for multiple near- and far-fault earthquakes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 30(4), 170–183 (2010).

Iervolino, I., Giorgio, M. & Chioccarelli, E. Closed-form aftershock reliability of damage-cumulating elastic-perfectly-plastic systems. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 43(4), 613–625 (2014).

Yu, X. H., Li, S., Lu, D. G. & Tao, J. Collapse capacity of inelastic single-degree-of-freedom systems subjected to mainshock-aftershock earthquake sequences. J. Earthquake Eng. 24(5), 803–826 (2020).

Ruiz-Garcia, J. & Negrete-Manriquez, J. C. Evaluation of drift demands in existing steel frames under as-recorded far-field and near-fault mainshock-aftershock seismic sequences. Eng. Struct. 33(2), 621–634 (2011).

Hatzivassiliou, M. & Hatzigeorgiou, G. D. Seismic sequence effects on three-dimensional reinforced concrete buildings. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 72, 77–88 (2015).

Goda, K. & Salami, M. R. Inelastic seismic demand estimation of wood-frame houses subjected to mainshock-aftershock sequences. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 12(2), 855–874 (2014).

Jamnani, H. H. et al. Energy distribution in RC Shear wall-frame structures subject to repeated earthquakes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 107, 116–128 (2018).

Goda, K. & Taylor, C. A. Effects of aftershocks on peak ductility demand due to strong ground motion records from shallow crustal earthquakes. Earthquake Eng. Struct. Dynam. 41(15), 2311–2330 (2012).

Ruiz-Garcia, J. Mainshock-aftershock ground motion features and their influence in building’s seismic response. J. Earthquake Eng. 16(5), 719–737 (2012).

Gupta, S. Scaling of response spectrum and duration for aftershocks. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 30(8), 724–735 (2010).

Li, Y., Song, R. & Van De Lindt, J. W. Collapse fragility of steel structures subjected to earthquake mainshock–aftershock sequences. J. Struct. Eng. 140, 04014095 (2014).

Goda, K. Record selection for aftershock incremental dynamic analysis. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 44(7), 1157–1162 (2015).

Papadopoulos, A. N., Kohrangi, M. & Bazzurro, P. Mainshock-consistent ground motion record selection for aftershock sequences. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 49(8), 754–771 (2020).

Gutenberg, B. & Richter, C. F. Frequency of earthquakes in California. (1944).

Bath, M. Lateral inhomogeneities of the upper mantle. Tectonophysics 2(6), 483–514 (1965).

Utsu, T., Ogata, Y. & Matsu’ura, R. S. The Centenary of the Omori formula for a decay law of aftershock activity. J. Phys. Earth. 43(1), 1–33 (1995).

Hu, S., Gardoni, P. & Xu, L. Stochastic procedure for the simulation of synthetic main shock-aftershock ground motion sequences. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 47(1), 2275–2296 (2018).

Turcotte, D. L., Holliday, J. R. & Rundle, J. B. BASS, an alternative to ETAS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34(12), 1–5 (2007).

Han, R. L., Li, Y. & de Lindt, J. V. Assessment of Seismic performance of buildings with incorporation of aftershocks. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 04014088. (2014).

Papadopoulos, A. N., Kohrangi, M. & Bazzurro, P. Correlation of spectral acceleration values of mainshock-aftershock ground motion pairs. Earthq. Spectra. 55(1), 39–60 (2018).

Zhu, R. G. et al. Conditional Mean spectrum of aftershocks. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 107(4), 1940–1953 (2017).

Hu, S., Tabandeh, A. & Gardoni, P. Modeling the Joint Probability Distribution of Main Shock and Aftershock Spectral Accelerations. 13th International Conference on Applications of Statistics and Probability in Civil Engineering. (2019).

Baker, J. W. & Cornell, C. A. Spectral shape, epsilon and record selection. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 35, 1077–1095 (2006).

Vahedian, V., Omranian, E. & Abdollahzadeh, G. A new method for generating aftershock records using artificial neural network. J. Earthquake Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2019.1664675 (2019).

Ding, Y. J., Chen, J. & Shen, J. X. Prediction of spectral accelerations of aftershock ground motion with deep learning method. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 150, 106951 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. FLAML: A fast and lightweight AutoML library. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 3: 434–447. (2021).

Ancheta, T. D. et al. NGA-West2 database. Earthq. Spectra. 30(3), 989–1005 (2014).

Aoi, S., Kunugi, T., Nakamura, H. & Fujiwara, H. Deployment of new strong motion seismographs of K-NET and KiK-net. Earthq. Data Eng. Seismology: Predictive Models Data Manage. Networks, 167–186. (2011).

Felicetta, C. et al. Italian Accelerometric Archive v4.0 - Istituto Nazionale Di Geofisica E Vulcanologia (Dipartimento della Protezione Civile Nazionale, 2023).

Gardner, J. K. & Knopoff, L. Is the sequence of earthquakes in Southern California, with aftershocks removed. Poissonian? Bull. Seismological Soc. Am. 1363–1367. (1974).

Holzer, T. L. Implications for earthquake risk reduction in the United States from the Kocaeli, Turkey, earthquake of August 17, 1999 (Vol. 1193). US Government Printing Office. (2000).

Kam, W. Y., Pampanin, S. & Elwood, K. Seismic performance of reinforced concrete buildings in the 22 February Christchurch (Lyttelton) earthquake. Bull. New. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 44(4), 239–278 (2011).

Goda, K. et al. Ground motion characteristics and shaking damage of the 11th March 2011 Mw9.0 Great East Japan earthquake. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 11(1), 141–170 (2013).

Wang, C., Wu, Q., Weimer, M. & Zhu, E. FLAML: A fast and lightweight automl library. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 3: 434–447. (2021).

Wu, Q., Wang, C. & Huang, S. Frugal optimization for cost-related hyperparameters. In AAAI’21, (2021).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst., 30. (2017).

Hancock, J. et al. An improved method of matching response spectra of recorded earthquake ground motion using wavelets. J. Earthquake Eng. 10(1), 67–89 (2006).

Abrahamson, N. A. Non-stationary spectral matching. Seismol. Res. Lett. 63(1), 30 (1992).

Lilhanand, K. & Tseng, W. S. Generation of synthetic time histories compatible with multiple-damping design response spectra. Transactions of the 9th international conference on structural mechanics in reactor technology. K1 (1987).

Lilhanand, K., Wen, S. & Tseng Development and application of realistic earthquake time histories compatible with multiple-damping design spectra. Proceedings of the 9th world conference on earthquake engineering 2. (1988).

Baker, J. W. & Jayaram, N. Correlation of spectral acceleration values from NGA ground motion models. Earthq. Spectra. 24(1), 299–317 (2008).

Ning, C. L., Wang, L. P. & Du, W. Q. A practical approach to predict the hysteresis loop of reinforced concrete columns failing in different modes. Constr. Build. Mater. 218, 644–656 (2019).

Goda, K., Hong, H. P. & Lee, C. S. Probabilistic characteristics of seismic ductility demand of SDOF systems with Bouc-Wen hysteretic behavior. J. Earthquake Eng. 600–622. (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by National Science Foundation of China (grant number. 52378506 and 52278492).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaohui Yu:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft; Meng Wang: Software, Validation; Chaolie Ning: Writing—Review & Editing; Kun Ji: Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Wang, M., Ning, C. et al. Predicting largest expected aftershock ground motions using automated machine learning (AutoML)-based scheme. Sci Rep 15, 942 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84668-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84668-7