Abstract

The integration of drug molecular representations into predictive models for Drug Response Prediction (DRP) is a standard procedure in pharmaceutical research and development. However, the comparative effectiveness of combining these representations with genetic profiles for DRP remains unclear. This study conducts a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy of various drug molecular representations employing cutting-edge machine learning models under various experimental settings. Our findings reveal that the inclusion of molecular representations from either PubChem fingerprints or SMILES can significantly enhance the performance of DRPs when used in conjunction with deep learning models. However, the optimal choice of drug molecular representation can vary depending on the predictive model and the specific DRP task. The insights derived from our study offer useful guidance on selecting the most suitable drug molecular representations for constructing efficient predictive models for DRPs, aiding for drug repurposing, personalized medicine, and new drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate drug response prediction (DRP), achieved by leveraging drug molecular information and genetic molecular profiles, plays a fundamental role in pharmaceutical research and development for drug repurposing, new drug development, and precision medicine1,2. For instance, in cancer therapy, where patients diagnosed with the same type of cancer may respond differently to identical treatments3,4,5,6, accurately predicting individual responses to candidate cancer treatments is crucial. This enables the identification of the most suitable options for each individual patient, thereby achieving optimal personalized outcomes. Such predictions represent a long-term goal in both basic science cancer research and pharmacological research. The usefulness of accurate DRPs extends beyond personalized treatment plans. In clinical trials, precise DRPs can significantly enhance the safety and efficacy of potential treatments, thereby increasing the success rate of these trials7. They facilitate the reduction of required sample sizes for trials by stratifying patients based on specific genomic characteristics8, leading to more efficient and cost-effective study designs. Furthermore, accurate DRPs improve patient outcomes by minimizing exposure to ineffective treatments and reducing adverse effects. In new drug discovery, accurate DRPs aid in the identification of possible biomarkers9,10,11 and new target compounds12, thereby averting a more costly and less efficient drug development process13,14,15. This not only accelerates the drug development pipeline but also enhances the likelihood of developing successful therapies.

Clinical trials in cancer research are limited by the size of subjects and drugs due to ethical concerns16 and affordability17,18, which makes them unsatisfactory and inefficient sources for DRP. Therefore, preclinical models, particularly cancer cell lines, become a crucial source for understanding drug mechanisms. Their large-scale and systematic nature offers significant advantages to DRP tasks in training machine learning models, despite the acknowledged limitations associated with the use of cultured cell lines16. From the pioneering NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen dataset19 to more recent ambitious initiatives such as the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)20 and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC)21, these rich cancer cell line data have served as versatile preclinical resources for cancer drug discovery22. These pharmacogenomic datasets harbor high-dimensional multi-omics profiles and pharmacological response data for hundreds of compounds across numerous cancer cell lines, facilitating the development and validation of effective DRP models17,23. In addition, data that represent drug structural information, such as drug molecular representations (the encoded molecular structure of drugs), have been increasingly included in predictive models for DRP to boost prediction performance24,25,26,27,28,29. These representations capture various structural features of drug molecules, including the presence or absence of specific substructures, functional groups, or molecular properties. There are two widely used types of drug molecular representations: numerical-based representations that include drug molecular fingerprints, and text-based representations. One common type of drug fingerprint is the PubChem fingerprint, which represents chemical structures as binary bit-strings, encoding structural features into a fixed-length binary format30. Another widely used numerical drug fingerprint is the Morgan fingerprint, which is one type of Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP). Morgan fingerprints are generated by systematically enumerating all substructures or circular atom environments within a specified radius around each atom in a chemical compound31. In addition to numerical representations, the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) is another popular type of drug representation. SMILES is a notation system used to represent the structure of chemical molecules in a simple and human-readable format using short ASCII strings. SMILES strings consist of alphanumeric characters and symbols that represent atoms, bonds, and other structural features of a molecule - capturing 2D and 3D drug molecular information, making them widely used tools in drug discovery32,33,34. In addition to these drug representations, drug graph representation is increasingly being used for drug response prediction35,36,37,38. However, it should be noted that drug graph representations are often constructed using SMILES37.

With the availability of large-scale cell line-drug screening databases20,21, numerous analytical methods have emerged to integrate drug molecular representations with cell line profile information for DRP using machine learning algorithms39. Broadly, these analytical methods fall into the following three categories. Firstly, the numerically encoded drug representations can be utilized to construct a similarity matrix, where each element represents the similarity between two drugs, with higher values indicating greater similarity. The similarity between each pair of drug molecules is computed using similarity metrics such as the Jaccard index (Tanimoto index) or Dice index40. These metrics gauge the similarity between two representations by comparing the presence or absence of features in each fingerprint, resulting in a symmetric similarity matrix. This constructed similarity matrix is then integrated into the matrix factorization model alongside the cell line profiles for DRP25,27. Another application of numerically encoded drug molecular representations involves incorporating the encoded numerical representations as individual features along with the cell line profile information into predictive models. These models include the elastic net and random forest41, kernel-based Bayesian models17, and deep learning models28,29,42. On the other hand, the text-based drug representation, SMILES, is exploited by using natural language processing (NLP) techniques to extract encodings and integrate with the cell line profiles in deep learning predictive models for DRPs32,33.

These methods - representing the most current DRP models, harness the rich information encapsulated in drug molecular representations and the cell line profiles to enhance the accuracy of DRPs, thereby contributing to advancements in precision medicine and drug discovery. In particular, machine learning methods offer great flexibility for modeling the complex associations among drug molecular representations, cell line profiles, and drug responses, potentially providing more accurate predictions compared to traditional parametric methods43. However, existing research has not systematically investigated whether drug molecular representations can significantly improve DRP accuracy in addition to cell line profiles. In other words, a central question to ask is: When cell line profiles are included in the predictive model, does the integration of drug molecular representations lead to a significant enhancement in DRP accuracy? To address this critical knowledge gap, this study comprehensively investigates the contribution of drug molecular representations to DRP when the cell line profile information is included. Specifically, we construct null drug representations (referred to as Null-Drug representations) and integrate them with cell line profiles for DRP. Simultaneously, the corresponding DRP is obtained from the same predictive method, but includes the actual drug molecular representations (referred to as With-Drug representations) and the cell line profiles. These two DRPs are then compared using a 10-fold cross-validation strategy to evaluate whether there is a significant difference between these two DRPs across various evaluation metrics.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: we present analysis results in the “Results” section, followed by a brief discussion. Details for constructing Null-Drug representations will be given at the end of the paper in the “Methods” section. Additionally, the metrics used to evaluate drug representations efficacy will be detailed in this section as well.

Results

Analysis results regarding the comparative effectiveness of drug representations for five DRP models under different data masking settings based on RMSE and PCC evaluation metrics are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Drug molecular representations comparative effectiveness in DRP

The results in Table 1 indicate that neither Morgan drug fingerprints nor PubChem fingerprints significantly enhance drug response predictions when used to construct the similarity matrix in matrix factorization models. In fact, including these fingerprints can decrease the accuracy of DRPs under the Mask-Pairs setting. For example, using PubChem fingerprints to construct the similarity matrix for DRPs with the SRMF model increased the RMSE by 36.4% and decreased the PCC by 10.3%, compared to using null drug representations. Similar results were observed when incorporating Morgan and PubChem fingerprints with genetic profiles for DRPs using the deep learning model PathDSP; these fingerprints did not improve prediction accuracy. Conversely, SMILES drug representations, PubChem fingerprints, 256-bit, 1024-bit, and 2048-bit Morgan fingerprints significantly improved DRP accuracy when integrated with genetic profiles using deep learning predictive models such as PaccMann and HiDRA. For instance, incorporating SMILES drug representations with genetic profiles in the PaccMann model decreased the RMSE by 15.5% and increased the PCC by 4.3%, compared to using SMILES null drug representations, with a p-value of 0.002 indicating statistical significance. Among these effective drug representations, the integration of PubChem fingerprints with genetic profiles in the HiDRA model yielded the best results, with the smallest predicted RMSE of 0.974 and the highest predicted PCC of 0.935. The predicted RMSE and PCC of these four drug representations with significant improvements in DRP are displayed in Fig. 1a, where the predicted RMSE is scaled by the predicted RMSE of SMILES using the PaccMann model, i.e., 1.137.

Table 2 results evidently indicate that no drug representations significantly improve DRP accuracy under the Mask-Cells setting, except for SMILES drug representations. Specifically, when SMILES drug representations are incorporated with genetic profiles in the deep learning PaccMann model, the predicted RMSE decreases by 12.0% and the PCC increases by 4.5% compared to using the SMILES null drug representations. Both improvements are statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.002. Results from Table 3 demonstrate that under the Mask-Drug setting, using Morgan fingerprints and PubChem fingerprints to construct a drug similarity matrix and incorporating it with genetic profiles in the matrix factorization model SRMF can significantly improve DRP accuracy, except when using the 512-bit Morgan fingerprints.

Additionally, incorporating similarity matrices constructed from all three types of Morgan fingerprints in the matrix factorization model ADRML can significantly improve DRPs. Moreover, incorporating PubChem fingerprints with genetic profiles in the deep learning model HiDRA not only significantly improves DRP accuracy, decreasing the predicted RMSE by 13.3% and increasing the PCC by 112.8%, but also achieves the most efficient prediction, with a predicted RMSE of 2.402 and a PCC of 0.449. This is displayed in Fig. 1b, where the predicted RMSE is scaled by the worst predicted RMSE (i.e., 3.539) via the ADRML model incorporating 1024-bit Morgan fingerprints. However, incorporating drug representations in PathDSP and PaccMann models does not significantly improve DRP performance.

The optimal DRP method for drug recommendations

To investigate the performance of the best method under each DRP application scenario for recommending the best drug and top-performing drug sets, i.e., HiDRA - PubChem for Mask-Pairs, PaccMann - SMILES for Mask-Cells, and HiDRA - PubChem for Mask-Drug, the corresponding recommendation rate plots are displayed in Fig. 2a,b. As shown in Fig. 2c, including PubChem drug fingerprints in the HiDRA model not only significantly improves DRP accuracy, but also ensures that the best-recommended drug from this method has a high chance of being included in the observed top 5 drug set. Additionally, there is a high likelihood (\(> 0.8\)) that the predicted top 10 drug set matches the actual top 10 drugs.

Similar observations can be seen in Fig. 2b for the Mask-Cells scenario. Including SMILES drug representations in the PaccMann model significantly enhances DRP and warrants that the best-recommended drug from this method has a large probability (\(\ge 0.8\)) of being contained in the observed top 5 drug set. Additionally, there is a high likelihood (\(\sim 0.8\)) that the predicted top 10 drug set matches the actual top 10 drugs. Though including PubChem drug fingerprints in the HiDRA model not only significantly improves DRPs, but also achieves the optimal prediction in terms of RMSE and PCC among those methods that can significantly enhance DRPs under the Mask-Drugs setting, the recommendation rate performance from this method is not ideal, as shown in Fig. 2c.

Discussion

Our study aimed to conduct a comprehensive assessment regarding the impact of integrating drug molecular representations with genetic profiles on DRP performance using five most recent state-of-the-art machine learning models. The findings have significant implications for drug repurposing, precision medicine, and new drug development. Our comprehensive evaluation revealed several key insights: (1) Enhanced Prediction Performance: Integrating drug molecular representations derived from PubChem fingerprints and SMILES significantly improved DRP accuracy when combined with genetic profiles. This enhancement was particularly pronounced in deep learning models, which are adept at capturing complex, non-linear relationships within the data; (2) Model-Specific Efficacy: The effectiveness of drug molecular representations varied across different machine learning models and DRP tasks. Deep learning models, such as HiDRA and PaccMann, demonstrated superior performance when incorporating drug molecular representations, highlighting the importance of selecting the appropriate model and representation for each specific task; (3) Context-Dependent Optimal Representations: Our results indicate that there is no one-size-fits-all solution regarding the choice of drug molecular representations. The optimal representation depends on the predictive model and the specific DRP scenario. For instance, the HiDRA model performed best with PubChem fingerprints in the Mask-Pairs scenario, while the PaccMann model showed significant improvements with SMILES representations in the Mask-Cells scenario.

These findings underscore the importance of incorporating rich drug molecular representations in DRP models to leverage their full predictive potential. This integration is crucial for advancing drug repurposing efforts, where existing drugs are evaluated for new therapeutic uses, and for developing precision medicine approaches that tailor treatments based on individual genetic profiles. Despite the promising results, several challenges and future research directions remain: (1) Data Integration and Complexity: Integrating diverse data sources, such as genetic profiles and molecular representations, increases the complexity of the models. Future research should focus on developing more robust methods to handle this complexity and enhance model interpretability; (2) Model Generalizability: Ensuring that DRP models generalize well across different datasets and experimental conditions is critical. Further studies should validate the findings across larger and more diverse datasets to confirm the robustness of the models; (3) Computational Resources: Deep learning models, although powerful, require significant computational resources. Developing more efficient algorithms that can achieve similar performance will be beneficial.

Our study provides strong evidence that integrating drug molecular representations with genetic profiles can significantly enhance the performance of DRP models. The optimal choice of representations and models is context-dependent, highlighting the need for careful selection and customization in DRP tasks. These findings offer useful insights for more accurate and effective drug repurposing, precision medicine, and new drug development efforts, ultimately improving patient outcomes and advancing pharmaceutical research.

Methods

Cell line-drug screening database

In this study, we meticulously leveraged the publicly available cell line-drug screening database, namely GDSC21, which encompasses a total of 312 cell lines and 144 drugs. We focused on investigating 36,836 cell-drug pairs as selected by Tang and Gottlieb28. The gene expression profiles of the cell lines and the corresponding drug response data for drug-cell pairs were obtained from GDSC. Drug responses were represented as the logarithm (Log) of IC50, with duplicated responses averaged. Canonical SMILES of drugs are retrieved from PubChem44. PubChem drug fingerprints were obtained using the PaDEL software45. Additionally, 256-bit, 512-bit, and 1024-bit Morgan fingerprints were computed using RDKit46.

Drug response prediction model

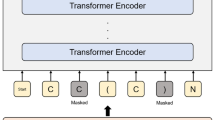

Five of the most recent DRP models were employed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of drug molecular representations on DRPs. Specifically, the matrix factorization models SRMF25 and ADRML27 were utilized to integrate Morgan or PubChem drug fingerprints similarity matrices and gene expression profiles similarity matrices for DRPs. Moreover, the deep learning model HiDRA29 incorporated Morgan or PubChem drug fingerprints and gene expression profiles as input features for DRPs. Additionally, the deep learning model PathDSP28 integrated Morgan or PubChem drug fingerprints and cell line pathway enrichment scores47 for DRPs. Furthermore, the deep learning model PaccMann33 included the text-based drug representations SMILES and gene expression profiles for DRPs, with SMILES strings extracted and converted into numerical vectors using NLP techniques (e.g., word embedding and encoding algorithms). The overall modeling procedures are presented in Fig. 3, with details of each DRP model described below.

Given a drug response matrix Y with \(Y_{ij}\) being the \(\text {ln(IC50)}\) corresponding to drug i and cell line j, the similarity-based matrix decomposition model SRMF is given as follows:

where \(W\) is the weight matrix with \(W_{ij} = 1\) if \(Y_{ij}\) is a known response value; otherwise, \(W_{ij} = 0\). W\(\cdot\)Z denotes the Hadamard product of two matrices W and Z. \(U\) and \(V\) are the latent matrices for drugs and cell lines, respectively, where \(U \in \mathbb {R}^{m \times k}\) and \(V \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times k}\). \(S_d\) is the drug similarity matrix. \(S_c\) is the cell line similarity matrix. \(\lambda _l\) is the regularization parameter for the latent matrices \(U\) and \(V\). \(\lambda _d\) is the regularization parameter for the drug similarity matrix \(S_d\). \(\lambda _c\) is the regularization parameter for the cell line similarity matrix \(S_c\). \(\left\| \cdot \right\| _F\) denotes the Frobenius norm. Drug response prediction is given as: \(\hat{Y} = \hat{U}\hat{V}^T\) with \(\hat{U} ,\hat{V}\) obtained by minimizing the loss function (1).

The similarity-based matrix factorization model ADRML is given as follows:

where \(U\) and \(V\) are the latent matrices for drugs and cell lines, respectively, with \(U \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times k}\) and \(V \in \mathbb {R}^{m \times k}\). \(\mathbf{u}_i\) is the ith row of U and \(\mathbf{v}_j\) is the jth row of V. \(\mu\) and \(\lambda\) are regularization coefficients. \(\text {S}_c\) and \(\text {S}_d\) are similarity matrices for cell lines and drugs, respectively. \(\left\| \cdot \right\|\) denotes the \(L_2\) norm of the vector. Drug response prediction is given by: \(\hat{Y} = \frac{1}{2}\hat{V}\hat{U}^T + \frac{1}{2}\hat{U}'\hat{V}'^T\) with \(\hat{U}, \hat{V}\) obtained by minimizing the loss function (2) using the observed ln(IC50) matrix \(Y\), and \(\hat{U}', \hat{V}'\) attained by minimizing the loss function (2) employing the transposed observed ln(IC50) matrix \(Y^T\) with initial input \(\hat{U}, \hat{V}\) for \(U, V\).

PathDSP28 is a 5-layer feed-forward fully-connected neural network model suggested by Li et al.25 using Pytorch for predicting \(\ln (\text {IC50})\), i.e., \(\hat{Y}\), as follows:

where X denotes concatenation of the drug features input and the pathway enrichment scores input calculated from cell line features that include drug targets, gene expression, mutation and copy number variation. \(f^{(\cdot )}\) are exponential linear unit (ELU) activation functions. \(W^{(\cdot )}\) and \(b^{(\cdot )}\) are weight and bias model parameters that need to be estimated. The number of nodes in the four hidden layers are 1,000, 800, 500 and 100, respectively. HiDRA29 is a deep learning model that includes four different networks: drug network, gene-level network, pathway-level network and response prediction network. For the response prediction network, it uses two dense layers to predict ln(IC50), i.e., a concatenation of the output from the drug network and the output from pathway-level network are used as the input. The drug network uses two dense layers to process drug molecular fingerprints and output a lower dimensional drug representation. The pathway-level network is an attention module that works with the gene-level network and generates lower dimensional cell line features. A rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function is used, and the only hidden layer includes 128 nodes.

PaccMann33 is a multihead-attention convolutional encoder employing attention mechanisms to leverage both gene expressions and SMILES sequences for the prediction of drug sensitivity \(\ln (\text {IC50})\). In the final stage, a stack of dense layers is used to predict the drug response, where the ReLU activation function is used and the number of nodes in the three hidden layers are 2,048, 1,024 and 512. The input, \({\mathbf { X}}\), to the model is the concatenation of the output from contextual attention layers, where

Here, \(\text {CA}_{i,j}\) denotes the output from the \(j\)th contextual attention layer of the \(i\)th channel. The model consists of four channels: three convolutional channels with different kernel sizes (3, 5, and 11) and one residual channel. Each convolutional channel processes the SMILES embeddings using a 1D convolutional neural network (CNN) to capture local patterns of varying lengths. The outputs from these CNNs, along with the raw embeddings from the residual channel, are then fed into four contextual attention layers. These attention layers use gene expression data as context to assess the importance of each part of the SMILES sequence, producing the contextually informed representations \(\text {CA}_{i,j}\).

Null drug representation construction

Each DRP model necessitates the input of drug representations to predict drug responses. To evaluate the impact of drug representations, DRPs should be obtained for both scenarios: with and without drug representations. Thus, each model is assessed under both “Null-Drug” and “With-Drug” experimental conditions. The “Null-Drug” setup aims to remove all information conveyed by drug representations while maintaining all other input variables identical to those in the “With-Drug” setup. This approach allows us to gauge the influence of drug representations on the performance of DRP models by comparing outcomes across these conditions. To establish the “Null-Drug” settings, we create null drug representations and incorporate them, along with the gene expression profiles, as input to the DRP model for DRPs. Correspondingly, we obtain DRPs from the same DRP model based on the actual drug representations and gene expression profiles. Depending on the drug molecular representations, we employ different strategies to construct the null drug representations. Configurations for the “Null-Drug” and “With-Drug” settings are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Specifically, an identity matrix is constructed to replace the similarity matrix used in the matrix factorization DRP models, i.e., SRMF and ADRML, for DRPs in the Null-Drug setting. The Null-Drug representations for both PubChem and Morgan fingerprints used in deep learning models HiDRA and PathDSP are constructed by randomly shuffling the corresponding PubChem and Morgan fingerprints. These randomly rearranged drug fingerprints were incorporated with the gene expression profiles for DRPs. Similarly, the Null-Drug representations for SMILES are constructed by randomly permuting the corresponding SMILES strings and including them in the deep learning model PaccMann for DRP. The constructed null drug representations effectively nullify the actual drug representation information.

Data masking strategies

When leveraging cell line profiles and drug molecular representations for DRPs under a supervised learning framework, there exist three common DRP tasks including: (i) predicting the response for future cell line and drug combinations (e.g., drug repurposing), (ii) predicting drug response for new patients to identify the optimal drug option (e.g., precision medicine), and (iii) predicting the response based on new drug molecular representations (e.g., new drug discovery)48,49. These types of DRP tasks play crucial roles in drug pharmaceutical research and precision medicine. For instance, accurately predicting the response of new (unknown) drug molecular compounds for established cell lines mirrors the process of new drug discovery which is important to identify potentially effective new drugs for targeted diseases.

To align with these DRP scenarios, we employed three distinct data masking settings: Mask-Pairs of cell lines and drugs (MP), Mask-Cells (MC), and Mask-Drugs (MD). These methods were devised to partition the data into training and testing sets, facilitating comprehensive evaluations of the impacts of drug representations corresponding to the three DRP tasks, respectively. In Mask-Pairs, data is divided based on cell line-drug pairs, ensuring that paired drug and cell line features in the testing samples are withheld during DRP model training. The Mask-Cells partitions the data by cells, guaranteeing that cell line features of the testing samples remain excluded from DRP model training. Similarly, the Mask-Drugs splits the data by drugs, preventing drug representations of the testing samples from influencing DRP model training. Specifically, in the MP scenario, 36,836 cell line-drug pairs were randomly divided into 10 approximately identical non-overlapping folds, with each fold alternately serving as the testing data while the remaining were used for training the DRP models. In the MC setting, the non-overlapping 10 folds were generated by randomly splitting the 312 cell lines, while in the MD scenario, the disjoint 10 folds were created by randomly dividing the 144 drugs. Furthermore, to ensure fair comparisons, we employed identical fold configurations across all DRP models in each specific masking strategy in training and testing DRP models for both the Null-Drug and With-Drug settings.

Performance evaluation metrics and test

To assess the performance of each model under both the Null-Drug and With-Drug settings, we adopted two evaluation metrics: root mean square error (RMSE), which quantifies the average squared root difference between the predicted and actual observed values, and Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), a measure of the strength and direction of the linear relationship between predicted and actual drug responses. The DRPs generated by each model under the Null-Drug and With-Drug settings in each round of the 10-fold cross-validation were then used to construct the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for each of the two evaluation metrics across the three masking settings.

In clinical practice, it is frequently required to suggest potentially top performing drugs. To assess the effectiveness of DRP models in practical clinical decision-making for effective drug recommendations using DRPs, we introduce the following ranking-based evaluation metric, referred to as the recommendation rate (RR), as defined below:

where c is the number of cell lines. \(\hat{D_{i}}(k)\) denotes the set of the predicted k best-performing drugs in cell i. \(D_{i}(k)\) stands for the set of the observed top k best-performing drugs for cell i. \(\mathbf{{I}}\) is the indicator function. \(\#\) is the cardinality (number of elements) of a set. \(RR_1\) can be interpreted as the probability of the model’s predicted best-performing drug being included in the actual top k performing drug set, indicating the likelihood of the number one predicted drug being recommended in the observed top k performing drug set. On the other hand, \(RR_2\) can be interpreted as the average overlapping rate between the predicted top k performing drug set and the observed top k performing drug set, i.e., the overlap between DRP recommendations and the actual observed rankings. Both \(RR_1\) and \(RR_2\) fall in the range between 0 and 1. The larger the value, the better the prediction accuracy. These two metrics provide a useful evaluation on how well the predicted drug response rankings align with the observed drug response rankings rather than focusing on evaluating the absolute differences between the predicted and observed drug response values.

Data availability

The drug response (IC50) and gene expression data are publicly available and obtained from the GDSC website (https://www.cancerrxgene.org). Canonical SMILES of drugs are retrieved from the PubChem website (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). PubChem fingerprints are obtained using the “PaDEL-Descriptor” software (http://yapcwsoft.com/dd/padeldescriptor/). The Morgan fingerprints data are calculated using the Python package “RDKit” (https://www.rdkit.org). The raw and preprocessed data used in the analysis are available on GitHub (https://github.com/lazypuff/DMF_in_DRP).

Code availability

We provide data preprocessing and analysis code for replicating this study on GitHub (https://github.com/lazypuff/DMF_in_DRP).

References

Yang, X., Yang, G. & Chu, J. The computational drug repositioning without negative sampling. EEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 20(2), 1506–1517 (2022).

Yang, X., Yang, G. & Chu, J. The neural metric factorization for computational drug repositioning. EEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 0(1), 731–741 (2022).

Staunton, J. E. et al. Chemosensitivity prediction by transcriptional profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 8(19), 10787–10792 (2001).

Ely, S. Personalized medicine: individualized care of cancer patients. Transl. Res. 154(6), 303–308 (2009).

Park, S. & Lehner, B. Cancer type-dependent genetic interactions between cancer driver alterations indicate plasticity of epistasis across cell types. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11(7), 824 (2015).

Geeleher, P., Cox, N. J. & Huang, R. S. Cancer biomarker discovery is improved by accounting for variability in general levels of drug sensitivity in pre-clinical models. Genome Biol. 17, 1–11 (2016).

Cook, J., Hunter, G. & Vernon, J. A. The future costs, risks and rewards of drug development: the economics of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacoeconomics 27, 355–363 (2009).

Lee, W., Lockhart, A. C., Kim, R. B. & Rothenberg, M. L. Cancer pharmacogenomics: powerful tools in cancer chemotherapy and drug development. Oncologist 10(2), 104–111 (2005).

Li, B. et al. Development of a drug-response modeling framework to identify cell line derived translational biomarkers that can predict treatment out- come to erlotinib or sorafenib. PLoS One 10(6), e0130700 (2015).

Oskooei, A., Manica, M., Mathis, R. & Martinez, M. R. Network-based biased tree ensembles (NetBiTE) for drug sensitivity prediction and drug sensitivity biomarker identification in cancer. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 15918 (2019).

Suphavilai, C., Bertrand, D. & Nagarajan, N. Predicting cancer drug response using a recommender system. Bioinformatics 34(22), 3907–3914 (2018).

Born, J. et al. PaccMannRL: De novo generation of hit-like anticancer molecules from transcriptomic data via reinforcement learning. Science 24(4), 102269 (2021).

Wong, C. H., Siah, K. W. & Lo, A. W. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics 20(2), 273–286 (2019).

Wouters, O. J., McKee, M. & Luyten, J. Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009–2018. JAMA 323(9), 844–853 (2020).

Scannell, J. W., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H. & Warrington, B. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R &D efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11(3), 191–200 (2012).

Firoozbakht, F., Yousefi, B. & Schwikowski, B. An overview of machine learning methods for monotherapy drug response prediction. Brief. Bioinform. 23(1), bbab408 (2022).

Costello, J. C. et al. A community effort to assess and improve drug sensitivity prediction algorithms. Nat. Biotechnol. 32(12), 1202–1212 (2014).

Adam, G. et al. Machine learning approaches to drug response prediction: challenges and recent progress. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 4(1), 19 (2020).

Shoemaker, R. H. The nci60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6(10), 813–823 (2006).

Barretina, J. et al. The cancer cell line encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483(7391), 603–607 (2012).

Yang, W. et al. Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(D1), D955–D961 (2012).

Weinstein, J. N. Cell lines battle cancer. Nature 483(7391), 544–545 (2012).

Cortes-Ciriano, I. et al. Improved large-scale prediction of growth inhibition patterns using the NCI60 cancer cell line panel. Bioinformatics 32(1), 85–95 (2016).

Chang, Y. et al. Cancer drug response profile scan (CDRscan): a deep learning model that predicts drug effectiveness from cancer genomic signature. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 8857 (2018).

Wang, L., Li, X., Zhang, L. & Gao, Q. Improved anticancer drug response prediction in cell lines using matrix factorization with similarity regularization. BMC Cancer 17(1), 1–12 (2017).

Liu, H., Zhao, Y., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Anti-cancer drug response prediction using neighbor-based collaborative filtering with global effect removal. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 13, 303–311 (2018).

Moughari, F. A. & Eslahchi, C. ADRML: anticancer drug response prediction using manifold learning. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 14245 (2020).

Tang, Y.-C. & Gottlieb, A. Explainable drug sensitivity prediction through cancer pathway enrichment. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3128 (2021).

Jin, I. & Nam, H. Hidra: hierarchical network for drug response prediction with attention. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1(8), 3858–3867 (2021).

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Pubchem subgraph fingerprint [Internet] (National Institutes of Health, 2009). https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/specifications/pubchem_fingerprints.pdf [cited 2022 February 1].

Morgan., H. L. The generation of a unique machine description for chemical structures—a technique developed at chemical abstracts service. J. Chem. Doc. 5(2), 107–113 (1965).

Liu, P., Li, H., Li, S. & Leung, K.-S. Improving prediction of phenotypic drug response on cancer cell lines using deep convolutional network. BMC Bioinform. 20(1), 1–14 (2019).

Cadow, J., Born, J., Manica, M., Oskooei, A. & Martinez, M. R. PaccMann: a web service for interpretable anticancer compound sensitivity prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 48(W1), W502–W508 (2020).

Goh, G. B., Hodas, N. O., Siegel, C. & Vishnu, A. SMILES2Vec: An interpretable general-purpose deep neural network for predicting chemical properties. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.02034 (2017).

Liu, Q., Zhiqiang, H., Jiang, R. & Zhou, M. DeepCDR: a hybrid graph convolutional network for predicting cancer drug response. Bioinformatics 36(Supplement 2), i911–i918 (2020).

Xia, X., Zhu, C., Zhong, F. & Liu, L. TransCDR: a deep learning model for enhancing the generalizability of drug activity prediction through transfer learning and multimodal data fusion. BMC Biol. 22(1), 227 (2024).

Yang, Y. & Li, P. GPDRP: a multimodal framework for drug response prediction with graph transformer. BMC Bioinform. 24(1), 484 (2023).

Yang, X., Yang, G. & Chu, J. GraphCL-DTA: a graph contrastive learning with molecular semantics for drug-target binding affinity prediction. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. (2024).

Menden, M. P. et al. Machine learning prediction of cancer cell sensitivity to drugs based on genomic and chemical properties. PLoS One 8(4), e61318 (2013).

Bajusz, D., Racz, A. & Heberger, K. Why is Tanimoto index an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations?. J. Cheminform. 7, 1–13 (2015).

Jang, I. S., Neto, E. C., Guinney, J., Friend, S. H. & Margolin, A. A. Systematic assessment of analytical methods for drug sensitivity prediction from cancer cell line data. In Biocomputing 2014, 63–74 (World Scientific, 2014).

Li, M. et al. DeepDSC: a deep learning method to predict drug sensitivity of cancer cell lines. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 18(2), 575–582 (2019).

Paltun, B. G., Mamitsuka, H. & Kaski, S. Improving drug response prediction by integrating multiple data sources: matrix factorization, kernel and network-based approaches. Brief. Bioinform. 22(1), 346–359 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Pubchem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D1373–D1380 (2023).

Yap, C. W. PaDEL-descriptor: An open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 32(7), 1466–1474 (2011).

RDKit. RdKit: Open-source cheminformatics. https://www.rdkit.org. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.591637

Fang, Z., Liu, X. & Peltz, G. GSEApy: a comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in python. Bioinformatics 39(1), btac757 (2023).

Chen, Y. & Zhang, L. How much can deep learning improve prediction of the responses to drugs in cancer cell lines?. Brief. Bioinform. 23(1), bbab378 (2022).

Pak, M., Lee, S., Sung, I. & Koo, B. Improved drug response prediction by drug target data integration via network-based profiling. Brief. Bioinform. 24(2), bbad034 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health R56 (1R56LM013784-01A1) and R01 (R01LM014407 and 1R01HL173044) grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Xiao, Q. Zheng and P. Popa conducted numerical analyses. B. Zou and F. Zou contributed to the methodology development and substantial writing and revising the manuscript. M. Xiao drafted initial manuscript version and all authors made significant contributions to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, M., Zheng, Q., Popa, P. et al. Drug molecular representations for drug response predictions: a comprehensive investigation via machine learning methods. Sci Rep 15, 20 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84711-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84711-7