Abstract

To retrospectively develop and validate an interpretable deep learning model and nomogram utilizing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) images to predict pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Following confirmation via pathological examination, a retrospective analysis was performed on a cohort of 266 patients, comprising 115 individuals diagnosed with PNETs and 151 with pancreatic cancer. These patients were randomly assigned to the training or test group in a 7:3 ratio. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator algorithm was employed to reduce the dimensionality of deep learning (DL) features extracted from pre-standardized EUS images. The retained nonzero coefficient features were subsequently applied to develop predictive eight DL models based on distinct machine learning algorithms. The optimal DL model was identified and used to establish a clinical signature, which subsequently informed the construction and evaluation of a nomogram. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) were implemented to interpret and visualize the model outputs. A total of 2048 DL features were initially extracted, from which only 27 features with coefficients greater than zero were retained. The support vector machine (SVM) DL model demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.948 and 0.795 in the training and test groups, respectively. Additionally, a nomogram was developed, incorporating both DL and clinical signatures, and was visually represented for practical application. Finally, the calibration curves, decision curve analysis (DCA) plots, and clinical impact curves (CIC) exhibited by the DL model and nomogram indicated high accuracy. The application of Grad-CAM and SHAP enhanced the interpretability of these models. These methodologies contributed substantial net benefits to clinical decision-making processes. A novel interpretable DL model and nomogram were developed and validated using EUS images, cooperating with machine learning algorithms. This approach demonstrates significant potential for enhancing the clinical applicability of EUS in predicting PNETs from pancreatic cancer, thereby offering valuable insights for future research and implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Originating from the neuroendocrine cells in the pancreas, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are part of a varied group of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs)1,2. The incidence of PNETs, the pancreas’s second most prevalent cancer type, is on the rise3. Based on the clinical symptoms displayed by patients, PNETs can be categorized into nonfunctional (NF-PNETs) and functional types (F-PNETs). The majority are nonfunctional tumors, often remaining symptomless for several years4. PNETs are diverse in nature, exhibiting unique clinical and histomorphology characteristics, and their prognosis varies5. The therapeutic approaches and prognoses for PNETs are markedly distinct from those associated with malignant pancreatic conditions such as pancreatic cancers6. Specifically, it is plausible to implement active surveillance without immediate surgical intervention for small NF-PNETs of less than or equal to 2 cm. Simultaneously, the utilization of somatostatin analogs for treating well-differentiated, low-grade F-PNETs is increasing. These strategies significantly diverge from the approach adopted for pancreatic cancer7,8,9. Consequently, the precise and timely diagnosis and differentiation of PNETs before surgical intervention is of utmost significance.

Among the imaging modalities available for diagnosing solid pancreatic tumors, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is the most effective, especially for detecting small lesions, surpassing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT)10. The literature reports an impressive sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 98% for EUS, which permits Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) biopsy and cytology, in addition to immunohistochemical staining for hormonal abnormalities. Before surgical intervention, EUS can ascertain the proximity of the PNETs to the main pancreatic duct, thereby supplying crucial data for an enucleation procedure11. EUS demonstrates exceptional sensitivity to NF-PNETs, particularly when their diminutive size obstructs their detection with alternative imaging techniques7,12,13. EUS is recognized as the most effective imaging modality for the pancreas; however, its efficacy is significantly influenced by the operator’s skill, resulting in considerable interobserver variability14. The advancement of computer-aided diagnosis and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms may facilitate decision-making in the management of pancreatic diseases13,15.

Advancements in computer-aided detection and AI have led to the rise of radiomics, a field that uses high-throughput techniques to extract and analyze image features. These features are then used to create various tumor diagnosis and prediction models through machine learning, deep learning, and other algorithms16,17. Recently, EUS imaging-based radiomics gradually rise. Previously, we reported several EUS imaging-based radiomics joint forecast model of machine learning algorithms that could effectively identify PNETs and pancreatic cancer, F-PNETs and NF-PNETs, and predict their pathological grading12,18,19. However, these machine-learning models are not visual or interpretable, limiting applicability.

The deep learning (DL) algorithm constitutes a variant of machine learning methodology that incorporates neural networks within its AI framework20. In contrast to conventional radiomics, DL-based radiomics strategies harness the intrinsic non-linearity of deep neural networks to autonomously learn pertinent features21. Furthermore, contemporary advancements in DL have demonstrated that radiomics features can be autonomously extracted via neural networks, devoid of human feature interaction, culminating in enhanced prediction performance22. Numerous studies have indicated that models utilizing enhanced CT images, enhanced ultrasound images, and enhanced MR images, in conjunction with DL algorithms, can effectively predict the risk of postoperative recurrence, invasiveness, and pathological grading of PNETs23,24,25. However, these models have not been visualized, rendering them non-interpretable. Moreover, despite EUS demonstrating superior performance in detecting PNETs, there is a notable paucity of research on models that integrate EUS images with DL. Furthermore, there is a significant gap in the literature regarding the interpretation and visualization of such models.

This study aimed to evaluate and validate the predictive efficacy of DL features extracted from standard EUS images in distinguishing PNETs from other pancreatic cancers. Concurrently, we integrated the models with Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) to elucidate and visualize the model outputs. We hypothesize that DL-clinical models augmented with the SHAP method could effectively and interpretably differentiate PNETs from pancreatic cancers.

Materials and methods

Clinical data

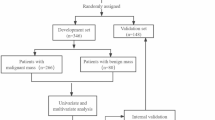

In this retrospective study, the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University approved the protocol (No. 2023-K346-01), exempting the need for patient consent or signed informed consent. The criteria for inclusion and exclusion are outlined below.

These criteria were used to determine eligibility: (1) undergo a meticulous EUS scan of the entire pancreas; (2) have proven pathological outcomes; (3) have complete, clear EUS images before preoperative or pathological biopsies; (4) chemotherapy or radiotherapy couldn’t be administered before EUS. It was excluded from the study patients who had tumors of other types, motion artifacts, or noise, or whose images did not show the whole lesion.

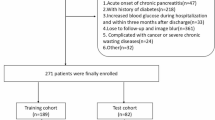

Finally, 266 participants were enrolled in this study, including 151 individuals with pancreatic cancer and 115 individuals with PNETs who underwent pancreatic surgery or endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration/biopsy (EUS-FNA/B) in our hospital from October 2014 to December 2023. Figure 1 illustrates how the training and test groups were randomized 7:3 among the registered individuals.

We retrospectively analyzed some clinical parameters and endoscopic ultrasonic features, such as age, gender, location of the pancreatic mass, maximum diameter, shape, margin characteristics, echo characteristics, uniformity of echo, calcification, and cystic features.

EUS examination and image acquisition

All enrolled patients underwent preoperative or pre-biopsy pancreatic EUS examinations using FUJIFILM SU-9000 and Olympus EU-ME2 equipment. An EUS specialist with more than 12,000 EUS procedures under his belt thoroughly examined the pancreatic area and obtained detailed images of the masses. In these images, a grayscale level of 125 values was consistently used, along with a grayscale window of 250 values. Our institution’s Picture Archive and Communication System (PACS) was used to obtain the imaging data.

Region of interest segmentation

During the study, two EUS specialists, each with over six years of experience and blinded to the histopathological diagnoses conducted a review of the EUS images of the enrolled patients. They selected the appropriate images and subsequently converted them to a consistent format. A region of interest (ROI) is manually outlined using the open-source software ITK-SNAP (version 3.8.1, http://www.itksnap.org). In conventional EUS images, the lesions were precisely delineated along their margins, with adjacent normal tissues, vessels, bile ducts, and pancreatic ducts excluded from the delineation. Through collaborative discussion and consensus, the specialists resolved discrepancies in their delineations. Subsequently, two specialists in consultation utilized the EUS macroscopic characteristics of pancreatic lesions. An overview of the situation is provided in Fig. 2.

To ensure reproducibility, standardization procedures were implemented in the preprocessing of images and data. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was utilized to assess both intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility. A cohort of 100 patients was randomly selected, and after a one-month interval, the same EUS specialists conducted the ROI segmentation again. An ICC greater than 0.80 was deemed indicative of satisfactory agreement.

Deep learning features extraction, selection, and signature building

In this study, an adapted version of the ResNet18 convolutional neural network (CNN) model was employed to extract DL features. To assess the areas emphasized by deep learning, we utilized the Grad-CAM method to generate saliency maps for every instance of pancreatic mass. A Z-score method was used to standardize the DL features. Finally, mean and variance (standard deviation) were calculated for each column.

Following the comparison of PNETs and pancreatic groups, Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted. Subsequently, feature selection was performed, retaining only those DL features that exhibited significance levels of p < 0.05 for further analysis. An evaluation of the interrelationship between features was conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. One of the two features exhibiting a correlation coefficient greater than 0.9 was retained through random selection. To further refine feature representation, a greedy recursive deletion strategy was implemented, whereby the most redundant feature within the current set was iteratively removed. The process of filtering out features with non-zero coefficients, selecting and reducing the dimensionality of fusion features, and obtaining the optimal subset of fusion features was accomplished through the application of the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO). Features with nonzero coefficients were preserved, conclusively. The LASSO regression analysis was conducted utilizing the scikit-learn package in Python, employing stratified tenfold cross-validation.

To establish a machine learning model, two key elements must be implemented: algorithmically selected features and modeling. a DL model was formulated by incorporating features with nonzero LASSO coefficients through a 5-fold cross-validation methodology, utilizing prevalent supervised machine learning algorithms, including random forest (RF), logistic regression (LR), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), extra trees, and multilayer perceptron (MLP). The models exhibiting superior performance were identified and defined as the DL signature, and the SHAP values of each retained feature with nonzero LASSO coefficients were computed to enhance the interpretability of the predictions generated by the optimal model. Additionally, various metrics, such as the ROC curve, decision curve analysis (DCA) curve, and confusion matrix, were utilized to assess the diagnostic performance of the DL signature. Ultimately, the machine learning algorithm employed for the development of the DL signature was identified as the most suitable algorithm for this study and was subsequently utilized for the training of the clinical signature.

Construction of clinical signature

Furthermore, the clinical predictor variables, including clinical and ultrasonic characteristics, were analyzed using univariate logistic regression analyses. Subsequently, to identify statistically significant clinical-ultrasonic features and to develop the clinical signature, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis. As a result, we were able to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for each variable as well as the 95% confidence interval (CI).

The same machine learning algorithm of the DL signature was used to create the clinical signature. For a fair comparison, a fixed 5-fold cross-validation and test cohort were applied. The model’s performance was assessed using metrics like AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Decision curve analysis (DCA) quantified the model’s net benefit in identifying pancreatic cancer and PNETs.

Nomogram establishment and assessment

The R rms package was used to create a nomogram for intuitively and efficiently differentiating PNETs from pancreatic cancer using combined DL and clinical signatures. Calibration was confirmed with a calibration curve, mean absolute error, and 1,000 bootstrap samples. DCA and clinical impact curve (CIC) assessed the nomogram’s net benefit and predictive performance.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ clinical parameters and DL features were compared using appropriate statistical tests such as independent sample t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or X2 tests. Statistical significance was determined by P < 0.05. Several metrics were used to evaluate prediction performance, including AUC, specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, and PPV. AUC was compared using Delong’s test. Figure 2 summarizes the comprehensive methodology for this study.

Results

Clinical characteristics statistics

266 patients were included in this retrospective study, 147 women and 119 men, randomly divided into two groups: training (N = 186) and testing (N = 80). The clinical characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. Clinical characteristics, except tumor location, differed significantly between the two groups. Notably, in comparison with pancreatic cancer, PNETs showed significantly smaller diameters, regular shapes, clear margins, uniform echos, and fewer cysts and calcifications. Furthermore, PNETs are independently predicted by mass shape and age in univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. A higher proportion of elderly individuals (OR 0.987; 95% CI 0.983 to 0.992) and those with unclear margins (OR 1.185; 95% CI 1.049 to 1.338) were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the study (Fig. 3).

Deep learning feature extraction and selection

During this study, we applied the CNN model (ResNet18) to extract 2048 DL features. A total of 178 deep learning (DL) features exhibited significant differences between the PNETs and pancreatic cancer groups. Subsequently, we compared and visualized the correlation coefficients of these DL features, retaining 107 DL features for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our findings indicated that the collinearity among the DL features was weak, suggesting that the DL model effectively captured these distinctions.

To investigate the interpretability of the deep learning regressor (DLR), we employed gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) to visualize the network. This method provides a rough localization map highlighting important regions relevant to the classification target. The last convolutional layer of the final residual block was made transparent for this purpose (Fig. 4). From the deep learning features, 27 features with non-zero coefficients were selected using a LASSO logistic regression model applied to the training group. The coefficients, mean standard error from 10-fold cross-validation, and the values of the coefficients for the finally selected non-zero features are presented in the accompanying Fig. 5.

Deep learning (DL) feature selection with the LASSO regression model. (A) The LASSO model’s tuning parameter (λ) selection used 10-fold cross-validation via minimum criterion. The vertical lines illustrate the optimal value of the LASSO tuning parameter (λ). (B) LASSO coefficient profile plot with different log (λ) was displayed. (C) The bar graph of 27 DL features that achieved nonzero coefficients.

Deep learning signature and performance

As shown in Fig. 6A and B, the ROC curves and AUCs of each DL model derived from the eight widely used machine learning algorithms are shown for the training and test groups. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates various machine learning algorithms’ performance metrics—accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and recall. Note that the RF, XGBoost, and ExtraTrees models tend to overfit. Compared to LR, KNN, LightGBM, and MLP models, the SVM model performed almost the best performance and showed stronger consistency between training (AUC = 0.948, 95% CI 0.9108–0.9854) and test groups (AUC = 0.795, 95% CI 0.6929–0.8968), demonstrating its effectiveness as an optimal DL model.

The performance of different machine learning models based on deep learning (DL) features that achieved nonzero coefficients. (A) The ROC curves of different DL models in the training group. (B) The ROC curves of different DL models in the test group. (C-D) The DCA curves for the SVM-based DL model (abbreviated “Model”) in the training (C) and (D) test groups. (E, F) The confusion matrix of the SVM-based DL model in the training (E) and test (F) groups.

This SVM-based DL model demonstrated an accuracy of 0.775, sensitivity of 0.805, specificity of 0.744, PPV of 0.767, and NPV of 0.784 in the test cohort (Table 2). Consequently, the SVM model was designated as the DL signature, deemed suitable for subsequent analyses, and selected as the foundational model. The preoperative prediction of PNETs using this SVM-based DL signature has demonstrated superior clinical benefits, as evidenced by DCA (Fig. 6C and D). The model’s predictive accuracy was validated through a confusion matrix (Fig. 6E and F). The prediction scores generated by the SVM-based DL model are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Explanation and visualization of the DL model

Shapley additive instruction (SHAP) is an approach to interpreting machine learning models’ output. Subsequently, with the SVM-based DL model, we implemented interpretable machine learning using the SHAP method. The importance of each feature of this model was analyzed by the SHAP method. Figure 7A shows the results of the feature importance analysis, with more important features distributed on the top and relatively unimportant features on the bottom. Most of the DL characteristics, either positively or negatively, correlated with the prediction results. SHAP summary plots visually displayed the importance and impact of features on the model’s output. Features were sorted by global importance, with each dot representing a patient’s SHAP value for a feature, plotted horizontally and stacked vertically to show density. Dots were colored from blue (low) to red (high) based on feature value. We found that DL_22 was the key feature for distinguishing PNETs/Pancreatic cancer classification. The density plot indicated varying SHAP values for this feature, and the model’s output increased as the feature’s value decreased.

(A) SHAP summary plots of SVM-based deep learning model. The plot illustrated the feature relevance and combined feature attributions to the model’s predictive performance. (B, C) SHAP force plots explained how the SVM-based model discriminates the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions. The predicted diagnosis of these pancreatic lesions was pancreatic cancer (B) and PNETs (C), respectively.

The force plot (Fig. 7B and C) illustrates a single patient’s assessment by showing each feature’s SHAP value as a force that increases or decreases the prediction, starting from the base value, the average SHAP value. The arrow length indicates the percentage contribution of each feature, while the color shows whether the contribution is positive (red) or negative (blue). As illustrated in Fig. 7B, the SHAP value for this patient was − 1.21, which is lower than the base value, thereby suggesting that this patient could be classified within the pancreatic cancer group. Conversely, another patient exhibited a SHAP value of 0.22, which exceeds the base value. Consequently, this patient could be classified under the PNETs category, as depicted in Fig. 7C.

Clinical signature

Subsequently, the SVM was selected as the foundational algorithm for the clinical signature. The SVM-based clinical model exhibited an accuracy of 0.812, a sensitivity of 0.730, a specificity of 0.866, a PPV of 0.783, and an NPV of 0.829 within the training group. An in-depth analysis of this model’s performance can be found in Table 2. Figure 8A illustrates the ROC curves and AUC values derived from the SVM-based clinical model for both the training (AUC = 0.823) and test (AUC = 0.847) groups. The clinical model exhibited an enhanced net advantage and augmented clinical applicability, as evidenced by the DCA curve (Fig. 8B). As a result, this SVM-based clinical model was identified as the clinical signature and utilized to develop an integrated nomogram for the prediction of PNETs from pancreatic cancers.

Construction and validation of the Nomogram

Subsequently, a comprehensive nomogram was constructed by employing logistic regression analysis of DL and clinical indicators, facilitated by the R rms package (Fig. 9). This was followed by the application of a calibration curve to assess the predictive accuracy of the nomogram. Within the training group, the calibration curve exhibited a minimal divergence between the actual and predicted probabilities of PNETs, with a mean absolute error of 0.013. This denotes the exceptional precision of the proposed nomogram model (Fig. 10A). To assess the pragmatic implementation of the model within a clinical context, a decision curve analysis was conducted and clinical impact curves were plotted. The outcome of the decision curve analysis revealed that the ‘Nomogram’ curve exhibited superior values in comparison to the ‘All’, ‘DL_Signature’, ‘Clinical_Signature’, and ‘None’ curves within the high-risk threshold, which extends approximately from 0 to 1.0 (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, a CIC was formulated based on the decision curve analysis to visually appraise the clinical effectiveness of the nomogram model. The close alignment of the “Number high risk” curve with the “Number high risk with event” curve within a high-risk threshold of 0.4 to 1.0 implies a remarkable predictive capacity of this nomogram model, as illustrated in Fig. 10C. Concurrently, the nomogram’s precision and practical application achieved optimal efficiency, corroborated by the calibration curve (Fig. 11A), DCA curve (Fig. 11B), and CIC (Fig. 11C) within the test group. A comprehensive examination of the performance of this nomogram is presented in Table 2. These findings suggest that the integration of the DL signature with the clinical signature could significantly enhance the prediction of PNETs.

The nomogram predicts PNETs based on clinical signature (abbreviated “Clinic_Sig”) and deep learning signature (abbreviated “DL_Sig”) simultaneously. The nomogram is used by summing all scores identified on the scale for each variable. The total score projected on the bottom scales indicates the probabilities of PNETs.

(A) The calibration curves for the nomogram with the mean absolute error = 0.013 in the training group. (B) Decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram and each strategy (the “All” means diagnosis-all strategy; the “None” means diagnosis-none strategy) in the training group. (C) The clinical impact curve (CIC) of the nomogram in the training group.

(A) The calibration curves for the nomogram with the mean absolute error = 0.03 in the test group. (B) Decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram and each strategy (the “All” means diagnosis-all strategy; the “None” means diagnosis-none strategy) in the test group. (C) The clinical impact curve (CIC) of the nomogram in the test group.

The Delong test was employed to contrast the clinical signature, DL signature, and Nomogram, as represented in Fig. 12, which delineates the ROCs and AUCs of diverse models in both the training and test cohorts. This nomogram accomplished an AUC of 0.967 in the training group and an AUC of 0.871 in the test group, which was superior to the clinical signature and not inferior to the DL signature, as evidenced in Table 3. This suggests that the utilization of this nomogram model may yield a significant net benefit for PNETs patients.

Discussion

This study developed multiple models to differentiate PNETs from pancreatic cancers by integrating EUS-based DL features with eight machine-learning algorithms utilizing ROI data. Our findings indicate that the combination of DL features and machine learning algorithms significantly enhances prediction accuracy for PNETs. Notably, the SVM model exhibited superior performance metrics, achieving an AUC of 0.948 (95% CI: 0.9108–0.9854) in the training group and an AUC of 0.795 (95% CI: 0.6929–0.8968) in the test group. Furthermore, the DL signature, in conjunction with the clinical signature, was employed to construct a nomogram for predicting PNETs. This nomogram demonstrated outstanding consistent efficacy and accuracy in both the training (AUC = 0.962, 95% CI: 0.939–0.984) and test (AUC = 0.871, 95% CI: 0.796–0.947) groups, as evidenced by ROC curves, calibration curves, DCA, and CICs. A previous study has reported that a radiomics model based on EUS imaging can effectively differentiate PNETs from pancreatic cancers, achieving an AUC of 1.000 (95% CI 1.000–1.000) in the training cohort and an AUC of 0.881 (95% CI: 0.800–0.962) in the test cohort18. However, this radiomics model appears to tend to overfit the training data. Additionally, our DL nomogram demonstrates exceptionally high calibration accuracy, as validated by 1,000 repeated samples. This represents the first demonstration that an EUS-based DL nomogram significantly and efficiently enhances the prediction of PNETs. Furthermore, Grad-CAM and SHAP values were utilized to elucidate and visualize the outputs of the DL model and the machine learning model, respectively, thereby significantly enhancing the interpretability of these models. Consequently, it was regarded as a reliable and valid tool for predicting PNETs and guiding treatment choices.

Although EUS is of great value in the detection and diagnosis of pancreatic masses, the diagnosis of EUS is highly dependent on the experience of the examiner, so the bias of different observers is large26. Furthermore, although EUS is widely employed as a cost-effective modality for the detection of PNETs, its diagnostic efficacy demonstrates variability across various published studies27. In the field of medical imaging, radiomics and DL are currently the most researched techniques28. Radiomics enables the identification of subtle alterations imperceptible to the human eye and enhances the extraction of high-quality quantitative data from images, surpassing traditional imaging modalities in this regard29. Recently, we introduced and confirmed a highly effective EUS-based radiomics model that integrates clinical-ultrasound and radiomics features for the prediction of pancreatic cancer and PNETs18. The findings of a multicenter study indicated the potential for creating an effective classification model for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) utilizing machine learning algorithms and EUS radiomics features30. Tang AL has reportedly developed an advanced artificial intelligence system utilizing contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound (CH-EUS) in conjunction with deep learning techniques to aid in the diagnosis of pancreatic masses, distinguishing between benign and malignant forms31. Despite its potential, the use of CH-EUS is limited by the requirement for specialized equipment and its inapplicability for patients with contrast agent allergies. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop a deep learning model utilizing conventional EUS images for the classification of pancreatic tumor types. However, a significant gap exists in the current literature, as there is a lack of published studies that leverage EUS imaging and deep learning features for the diagnosis and prediction of PNETs.

Recently, there has been a significant surge in interest regarding the application of DL techniques in the analysis of medical images, including radiologic imaging32. DL techniques have the capability to extract more sophisticated and higher-level features from data compared to traditional machine learning methods33. A notable advantage of employing deep learning is the elimination of the need for handcrafted features within the algorithms. Deep learning algorithms are regarded as superior in learning abstract features from basic ones, which can be particularly beneficial for the development of AI models34. Furthermore, there are powerful generalization and learning capabilities in deep learning models35. A DL radiomics model utilizing EUS images for the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was developed, demonstrating efficacy in reducing diagnostic discrepancies among EUS practitioners with differing levels of expertise, thus improving diagnostic accuracy. In this context, we also developed and validated an effective nomogram that incorporates DL features alongside clinical ultrasound characteristics for the prediction of PNETs.

A convolutional neural network (CNN) is one of the most prominent mechanisms of DL technologies and is widely used in medical image analysis36,37. Deep Residual Networks (ResNet)are exceptionally deep CNN architectures that are used for recognizing images, identifying objects, and locating them38. ResNet and similar architectures have become prevalent in image processing, exemplifying cutting-edge advancements in image recognition39. As a result of ResNet’s superior performance, gradient disappearance is effectively addressed in deep learning training40. The ResNet architecture encompasses several variants, including ResNet18, ResNet34, and ResNet50, with ResNet18 comprising the fewest layers and ResNet50 the most41. The training duration can be minimized by leveraging knowledge transfer from a pre-trained ResNet18, which has demonstrated high efficacy in medical image recognition and prediction tasks42,43. Consequently, ResNet18 was chosen as the foundational model for this training framework.

Our research demonstrated that an extensive array of 2048 DL features derived from the ResNet18 model was initially extracted from EUS imaging. Following this, a series of rigorous statistical analyses—including t-test analysis, correlation analysis, and LASSO regression—enabled the identification of a subset of 27 DL features that were found to be highly significant and definitively associated with PNETs and applied to further analysis. Utilizing Grad-CAM, AI can delineate regions of interest within images44. Consequently, we employed Grad-CAM technology to propose a visual representation that elucidates the inferential processes underlying the original images. Through the size and color of the circles, Grad-CAM illustrates the importance of important regions. Furthermore, Grad-CAM validated the primary features extracted, offering a visual model that traces the origin of these features. Finally, the generation of Grad-CAM visualizations afforded us a deeper understanding of the classification mechanisms for correctly identified photographs of pancreatic masses via the ResNet18 model.

Numerous clinical prediction models have recently been developed utilizing machine learning methodologies45. Integrating radiomics with machine learning techniques has demonstrated substantial prognostic accuracy in oncology46. Many studies have highlighted the effectiveness of combining machine learning and radiomics for diagnosing and predicting PNETs47,48. Similar to those in previous studies, to address the limitations inherent in single-algorithm approaches, multiple mainstream machine learning algorithms were concurrently employed to develop an optimal two-class prediction model for distinguishing PNETs from pancreatic cancer. Among these, the SVM algorithm exhibited superior accuracy and consistency, leading to its selection for subsequent model refinement and development.

In the context of data mining algorithms, SVM is regarded as a robust and accurate approach to supervised learning. Our findings indicated that both the DL signature model and the clinical signature model, utilizing the SVM algorithm, achieved commendable AUC values and demonstrated significant performance. However, the limited interpretability of these machine learning models has constrained the application of radiomics-based studies in clinical practice. Consistent with previous literature18,47,48, machine learning algorithms often yield results that are challenging to interpret, thereby hindering clinicians’ ability to integrate these solutions into their practice effectively.

“Black-box features” are widely known to be machine learning’s shortcomings. To uncover the “black box” of ML, Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) values were used to explain the machine learning model and evaluate each variable’s prediction49. SHAP assigns an importance value, referred to as a SHAP value, to each feature; positive SHAP values signify an increased likelihood of the corresponding class, whereas negative SHAP values denote a decreased likelihood50. Recently, leveraging the SHAP technique, a CT radiomics-based interpretable machine learning model was reported to effectively predict the pathological grade of PNETs in a non-invasive manner51. Similarly, we employed SHAP values to visualize the contribution of each nonzero DL feature for SVM models and individual patients. Summary plots based on SHAP values intuitively demonstrated the importance of DL features, elucidating the reasons behind the SVM model’s prediction outcomes for each patient. In this study, analyzing the EUS image of a specific pancreatic mass enables the precise calculation of the SHAP value for each non-zero DL feature. This process ultimately facilitates the determination of the final prediction outcome of the mass using this SVM classifier model, thereby guiding clinical diagnosis and decision-making.

Consequently, in addition to the high accuracy of the EUS-based DL model developed in this study, its notable contribution resides in its interpretability. Moreover, to our knowledge, this investigation is the first to report that a novel DL model based on EUS imaging can predict PNETs from pancreatic cancer with remarkable accuracy.

As previously elucidated through univariate and multivariate analyses, our study presents evidence suggesting that patients with PNETs tend to be younger and that these tumors are more likely to exhibit clear margins compared to pancreatic cancer. Consistent with our outcomes, a previous study illustrated a statistically significant age difference between patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and those with PNETs52. Additionally, PNETs were frequently characterized by well-defined borders, regular round shapes, and uniform internal echo patterns53. Consequently, the clinical characteristics and ultrasonic features of EUS are integral to accurate diagnosis, which were utilized to develop a clinical signature. Furthermore, a visual nomogram for predicting PNETs was created by integrating both clinical and DL signatures, demonstrating remarkable efficacy and accuracy in both training and testing groups, as supported by calibration curves, DCA curves, and CICs. Therefore, this nomogram is considered a reliable and valid tool for predicting PNETs and informing treatment decisions.

Although the explicable DL model and nomogram utilizing EUS imaging demonstrated significant efficacy, this study is constrained by several limitations. Retrospective analyses conducted at a single center are susceptible to selection bias, and the manual segmentation process may introduce additional bias in image segmentation54. Furthermore, we employed EUS imaging utilizing two heterogeneous devices from distinct manufacturers, which could introduce potential noise and bias despite the application of standardization procedures. Additionally, the limited sample size may result in reduced generalizability. Therefore, it is imperative for future EUS-based deep learning research aimed at predicting PNETs to incorporate larger sample sizes, prospective designs, and multimodal approaches. Additionally, for this nomogram to be considered externally applicable, it should also undergo multicenter clinical validation. Furthermore, combining deep learning methodologies and investigating the underlying biological alterations of intratumoral habitat characteristics could reduce bias and improve the interpretability of the models. Additionally, future studies should consider implementing automatic image segmentation technology for EUS images.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a novel interpretable DL model and nomogram were developed and validated using EUS images, cooperating with machine learning algorithms. This approach demonstrates significant potential for enhancing the clinical applicability of EUS in predicting PNETs from pancreatic cancer, thereby offering valuable insights for future research and implementation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Detailed contributions to the study are included in the article/supplements; corresponding authors can be contacted for further inquiries.For access to the data, please contact Prof. Haixing Jiang of Guangxi Medical University in China (Email address: Jianghaixing@gxmu.edu.cn). The authors have adhered to all ethical and legal requirements for data sharing and have provided all necessary information for replication of the study.

References

Hu, Y. et al. Role of somatostatin receptor in pancreatic neuroendocrine Tumor Development, diagnosis, and Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 679000 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. RHAMM(B)-mediated bifunctional nanotherapy targeting Bcl-xL and mitochondria for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor treatment. Mol. Therapy Oncolytics. 23, 277–287 (2021).

Yang, Z., Liu, C., Leng, K., Liu, L. & Shi, G. Early-onset pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a distinct disease with improved survival compared with old individuals. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1025485 (2023).

Si, Y. et al. Analysis of Prognostic Risk Factors of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) and Curative Resection of Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Contrast media & molecular imaging (2022) 5248256. (2022).

Calabrò, D., Argalia, G. & Ambrosini, V. Role of PET/CT and Therapy Management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Diagnostics (Basel Switzerland) 10 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. A deep learning-based segmentation system for rapid onsite cytologic pathology evaluation of pancreatic masses: a retrospective, multicenter, diagnostic study. EBioMedicine 80, 104022 (2022).

Kos-Kudła, B. et al. Fazio, European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J. Neuroendocrinol. 35, e13343 (2023).

Alfaraj, D., AlOtaibi, R. O., Bamousa, R. M. & Alzamami, J. F. Pathological fracture as the initial presentation of metastatic pancreatic Cancer. Cureus 14, e20920 (2022).

Liu, T., Xu, Q., Zou, X., Zhu, L. & Zhao, Y. Mind the tributary of the canal: are stents necessary for insulinoma enucleation in proximity to a prominent Duct of Santorini: a case report and literature review. Medicine 101, e31211 (2022).

Melita, G., Pallio, S., Tortora, A., Crinò, S. F. & Macrì, A. and G. Dionigi, Diagnostic and Interventional Role of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the management of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. J. Clin. Med. 10 (2021).

Hofland, J. et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society 2023 guidance paper for functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour syndromes. J. Neuroendocrinol. 35, e13318 (2023).

Mo, C. H. S., Wang, Y., Wu, W. & Qin, S. H. A novel endoscopic ultrasomics-based machine learning model and nomogram to predict the pathological grading of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Heliyon 10, e34344 (2024).

Vitali, F. et al. Diagnostic endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatology: focus on normal variants and pancreatic masses. Visc. Med. 39, 121–130 (2023).

Serrao, E. M. et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting of the pancreas at 1.5 T and 3.0 T. Sci. Rep. 10, 17563 (2020).

Kuwahara, T. et al. Artificial intelligence using deep learning analysis of endoscopic ultrasonography images for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic masses. Endoscopy 55, 140–149 (2023).

Parasher, G., Wong, M. & Rawat, M. Evolving role of artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 7287–7298 (2020).

M. Kocher, Artificial intelligence and radiomics for radiation oncology. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie: Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft … et al] 196 (2020) 847.

Mo, S. et al. Construction and validation of an endoscopic ultrasonography-based ultrasomics nomogram for differentiating pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors from pancreatic cancer. Front. Oncol. 14, 1359364 (2024).

Mo, S. et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-based intratumoral and peritumoral machine learning radiomics analyses for distinguishing insulinomas from non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1383814 (2024).

Yu, J., Zhang, Y., Zheng, J., Jia, M. & Lu, X. Ultrasound images-based deep learning radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of RET rearrangement in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1062571 (2022).

Lombardo, E. et al. Distant metastasis time to event analysis with CNNs in independent head and neck cancer cohorts. Sci. Rep. 11, 6418 (2021).

Farina, B. et al. Integration of longitudinal deep-radiomics and clinical data improves the prediction of durable benefits to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients. J. Translational Med. 21, 174 (2023).

Song, C. et al. Predicting the recurrence risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms after radical resection using deep learning radiomics with preoperative computed tomography images. Annals Translational Med. 9, 833 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Development and validation of a combined nomogram model based on deep learning contrast-enhanced ultrasound and clinical factors to predict preoperative aggressiveness in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur. Radiol. 32, 7965–7975 (2022).

Gao, X. & Wang, X. Deep learning for World Health Organization grades of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images: a preliminary study. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 14, 1981–1991 (2019).

Ding, H. et al. Combining endoscopic ultrasound and tumor markers improves the diagnostic yield on the etiology of common bile duct dilation secondary to periampullary pathologies. Annals Translational Med. 7, 314 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasound for detecting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 363, 511–518 (2022).

Ge, G. & Zhang, J. Feature selection methods and predictive models in CT lung cancer radiomics. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 24, e13869 (2023).

Yang, Y., Zhang, X. X., Zhao, L., Wang, J. & Guo, W. L. Development of a simplified model and nomogram in preoperative diagnosis of pediatric chronic cholangitis with pancreaticobiliary maljunction using clinical variables and MRI radiomics. Insights into Imaging. 14, 41 (2023).

Li, X., Jiang, F., Guo, Y., Jin, Z. & Wang, Y. Computer-aided diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a radiomics method on endoscopic ultrasound image. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 14, 1635–1645 (2019).

Tang, A. et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound (CH-EUS) MASTER: a novel deep learning-based system in pancreatic mass diagnosis. Cancer Med. 12, 7962–7973 (2023).

Jia, F., Wang, S. & Pham, V. T. A hybrid catheter localisation Framework in Echocardiography based on Electromagnetic Tracking and Deep Learning Segmentation. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2119070 (2022).

Qi, W., Chen, R., Chen, M., Zhao, M. & Wang, M. Evaluation Analysis of the Nephrotoxicity of Tripterygium wilfordii Preparations with CONSORT Harms Statement Based on Deep Learning. Journal of healthcare engineering (2022) 5054932. (2022).

White, C., Ismail, H. D., Saigo, H. & Kc, D. B. CNN-BLPred: a convolutional neural network based predictor for β-Lactamases (BL) and their classes. BMC Bioinform. 18, 577 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Deep learning PET/CT-based radiomics integrates clinical data: a feasibility study to distinguish between Tuberculosis nodules and lung cancer. Thorac. cancer. 14, 1802–1811 (2023).

Chen, X., Men, K., Li, Y., Yi, J. & Dai, J. A feasibility study on an automated method to generate patient-specific dose distributions for radiotherapy using deep learning. Med. Phys. 46, 56–64 (2019).

Li, L., Li, Z. M. & Wang, Y. Z. A method of two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy combined with residual neural network for comparison and differentiation of medicinal plants raw materials superior to traditional machine learning: a case study on Eucommia ulmoides leaves. Plant. Methods. 18, 102 (2022).

Baig, A. R. et al. Light-Dermo: a lightweight pretrained convolution neural network for the diagnosis of Multiclass skin lesions. Diagnostics (Basel Switzerland) 13 (2023).

Schlicht, S., Jaksch, A. & Drummer, D. Inline Quality Control through Optical Deep Learning-Based Porosity Determination for Powder Bed Fusion of Polymers. Polymers 14 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. TransPhos: a deep-learning model for General Phosphorylation Site Prediction based on Transformer-Encoder Architecture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022).

Li, H. & Boulanger, P. Structural anomalies detection from Electrocardiogram (ECG) with Spectrogram and Handcrafted features. Sens. (Basel Switzerland) 22 (2022).

Rosenberg, G. S. et al. Artificial Intelligence accurately detects traumatic thoracolumbar fractures on sagittal radiographs. Med. (Kaunas Lithuania) 58 (2022).

Alharbe, N. R. et al. Atom search optimization with the deep transfer learning-driven esophageal Cancer classification model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 4629178 (2022).

Kawauchi, K. et al. A convolutional neural network-based system to classify patients using FDG PET/CT examinations. BMC cancer. 20, 227 (2020).

Guo, C. et al. A prediction model for massive hemorrhage in trauma: a retrospective observational study. BMC Emerg. Med. 22, 180 (2022).

Wan, S. et al. CT-based machine learning radiomics predicts CCR5 expression level and survival in ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 16, 1 (2023).

Javed, A. A. et al. Accurate non-invasive grading of nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with a CT derived radiomics signature. Diagn. Interv. Imaging. 105, 33–39 (2024).

Gu, D. et al. CT radiomics may predict the grade of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 29, 6880–6890 (2019).

Cui, C. et al. A prediction and interpretation machine learning framework of mortality risk among severe infection patients with pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Med. 9, 942356 (2022).

Yap, M. et al. Verifying explainability of a deep learning tissue classifier trained on RNA-seq data. Sci. Rep. 11, 2641 (2021).

Ye, J. Y. et al. A radiomics-based interpretable model to predict the pathological grade of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur. Radiol. 34, 1994–2005 (2024).

Iordache, S. et al. Power Doppler endoscopic ultrasound for the assessment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopic Ultrasound. 1, 150–155 (2012).

Di Leo, M. et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: the role of endoscopic ultrasound biopsy in diagnosis and Grading based on the WHO 2017 classification. Digestive diseases. (Basel Switzerland). 37, 325–333 (2019).

P. Lohmann, K. Bousabarah, M. Hoevels, and H. Treuer, Radiomics in radiation oncology-basics,methods, and limitations. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie: Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft… et al] 196 (2020) 848–855.

Acknowledgements

The Onekey AI platform and its developers deserve our appreciation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Liuzhou People’s Hospital affiliated with Guangxi Medical University (grant numbers: lry202309 and lry202311), The Scientific Research Project of Liuzhou Science and Technology Bureau (grant number: 2024YB0101B005). Guangxi Medical and Health Appropriate Technology Development and Promotion Project (Approval No. S2024016). The Scientifc Research Project of Guangxi Health Commission (grant number: Z-B20231296, Z-B20241298).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors N.Y., S.M., Y.Z., and Q.J . designed this study and drafted the manuscript; therefore, they contributed equally to the work and shared the first authorship. N.Y. performed the statistical analyses. S.M. and Y.Z. carried out the clinical data collection manuscript writing. S.Q. and HJ provided funding support and achieved senior authorship. Y. W. and C. reviewed the manuscript. Final approval of the manuscript was obtained from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Following the Declaration of Helsinki, this retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (No. 2023-K346-01, 2023-12-29). Considering the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was not required. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We confirm that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. The retrospective study have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, N., Mo, S., Zhang, Y. et al. An endoscopic ultrasound-based interpretable deep learning model and nomogram for distinguishing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors from pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep 15, 3383 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84749-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84749-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interpretable deep learning model and nomogram for predicting pathological grading of PNETs based on endoscopic ultrasound

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2025)