Abstract

Skin cancer is common and deadly, hence a correct diagnosis at an early age is essential. Effective therapy depends on precise classification of the several skin cancer forms, each with special traits. Because dermoscopy and other sophisticated imaging methods produce detailed lesion images, early detection has been enhanced. It’s still difficult to analyze the images to differentiate benign from malignant tumors, though. Better predictive modeling methods are needed since the diagnostic procedures used now frequently produce inaccurate and inconsistent results. In dermatology, Machine learning (ML) models are becoming essential for the automatic detection and classification of skin cancer lesions from image data. With the ensemble model, which mix several ML approaches to take use of their advantages and lessen their disadvantages, this work seeks to improve skin cancer predictions. We introduce a new method, the Max Voting method, for optimization of skin cancer classification. On the HAM10000 and ISIC 2018 datasets, we trained and assessed three distinct ML models: Random Forest (RF), Multi-layer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPN), and Support Vector Machine (SVM). Overall performance was increased by the combined predictions made with the Max Voting technique. Moreover, feature vectors that were optimally produced from image data by a Genetic Algorithm (GA) were given to the ML models. We demonstrate that the Max Voting method greatly improves predictive performance, reaching an accuracy of 94.70% and producing the best results for F1-measure, recall, and precision. The most dependable and robust approach turned out to be Max Voting, which combines the benefits of numerous pre-trained ML models to provide a new and efficient method for classifying skin cancer lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin cancer, which is prevalent globally and occasionally life-threatening1,2, poses significant challenges for healthcare providers. Effective patient treatment requires precise diagnosis and classification of various types of skin cancer. Selecting an appropriate treatment plan is crucial, as each type of skin cancer possesses distinct characteristics that complicate predictive modeling. Among the types, melanoma3,4,5 is particularly concerning due to its tendency to metastasize more readily. Advanced imaging techniques like dermoscopy6 have notably enhanced the early diagnosis of skin cancers. These high-resolution imaging methods enable the detection of specific features in skin lesions that may indicate malignancy. However, the main challenge remains accurately analyzing these images to identify the specific type of skin cancer and differentiate between benign and malignant cells. The complexity of skin cancer diagnosis is compounded by the diversity of skin conditions and the limitations of current diagnostic techniques, which often lead to inconsistent and inaccurate diagnoses.

Physical examinations and biopsies, while standard, are time-consuming, invasive, and often subject to human error due to variability in clinical expertise and interpretation. Visual inspections of skin lesions can lead to inconsistent diagnoses, as subtle differences between benign and malignant lesions may not be easily discernible. Moreover, even with advanced imaging techniques like dermoscopy, the analysis of high-resolution images relies heavily on subjective interpretation. These limitations underscore the necessity for more accurate, non-invasive diagnostic tools that can enhance early detection and reduce the likelihood of misdiagnosis, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Recently, numerous machine learning methods have been explored for applications across various fields7,8,9,10,11. Machine learning (ML) has the potential to revolutionize dermatology by addressing many of the challenges faced in traditional skin cancer diagnosis12,13,14,15,16. ML models can analyze large datasets of dermoscopic images more rapidly and accurately than human clinicians, providing consistent, objective assessments free from human bias. Furthermore, ML models are capable of identifying subtle patterns and features within images that may be undetectable to the human eye, offering the potential for earlier detection of malignancies like melanoma, where early diagnosis significantly improves survival rates. Additionally, ML-based tools can be deployed in remote areas or regions with limited access to specialized dermatologists, enhancing the reach of expert diagnostic capabilities through telemedicine. As these models continue to improve with more extensive training data, they will provide robust decision-support systems that can assist dermatologists in formulating personalized treatment plans, improving patient outcomes, and streamlining clinical workflows.

While existing ML models, such as SVMs, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and RFs, have shown promise, they are often limited by their reliance on specific datasets and their inability to generalize well across different skin lesion types. Moreover, many of these models are confined to binary classification tasks, focusing solely on distinguishing between melanoma and non-melanoma lesions. Our proposed approach introduces a novel Max Voting ensemble method that combines the strengths of multiple pre-trained models, including RF, MLPN, and SVM, to achieve multi-class classification. Additionally, the integration of a Genetic Algorithm (GA) for optimized feature extraction further enhances the model’s performance by selecting the most relevant image features. This dual approach of ensemble learning with optimal feature extraction significantly improves predictive accuracy, robustness, and generalizability across different datasets.

The main concerns motivating this research are multiple. First of all, there is a great deal of variability in diagnosis since subjectivity and human mistake sometimes lead to incorrect conclusions from present diagnostic techniques. This unpredictability can result in wrong diagnosis and unsuitable course of therapy. Furthermore, a large number of the current ML models are limited to binary categorization. This drawback makes them less useful in actual situations when it is necessary to identify several kinds of skin abnormalities. Finally, overfitting might result from the significant dependence on certain datasets for both training and testing. This dependence limits the model’s usefulness in more extensive clinical applications by reducing its capacity to generalize to fresh and varied data.

This study is grounded on the following hypotheses: First, we anticipate that ensemble learning models will outperform individual machine learning models in terms of prediction resilience and accuracy. Implementing a standardized assessment system is expected to enhance the consistency and comparability of results across various studies and datasets. Finally, we hypothesize that expanding the range of classified skin lesion types will increase the applicability of the machine learning model in clinical settings.

This study primarily seeks to establish a reliable and precise ML framework aimed at classifying multiple types of skin cancer from dermoscopic images. By leveraging an ensemble learning approach, combined with a Genetic Algorithm for feature optimization, this study aims to significantly improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce variability in diagnoses, and ultimately support early and reliable detection of various skin cancer types, thus improving patient outcomes.

Our Contributions include:

-

This work aims to investigate a unique use of the Max Voting approach to enhance the precision and dependability of skin cancer lesion classification.

-

By using the advantages of several pre-trained ML models, such as RF, MLPN, and SVM, the suggested approach shows improved accuracy and resilience.

-

A Genetic Algorithm (GA) was used to produce optimal feature vectors from a collection of images. Then, increasingly sophisticated ML classification methods made use of these vectors.

-

We combined modern ML techniques with the field of healthcare to create a novel and effective approach to categorizing skin cancer lesions.

This work is arranged as follows: Review of the literature is found in section “Literature review”. Section “Proposed method” describes in detail the suggested method. The simulation results and an extensive discussion are presented in section “Results and its discussion”. A summary and some concluding views are included at the end of section “Conclusion”.

Literature review

ML has proven to be instrumental in automating skin cancer diagnosis, offering substantial improvements over traditional diagnostic approaches. This review explores key machine learning approaches applied in skin cancer diagnosis, and current limitations, while setting up the need for a novel ensemble approach combining Genetic Algorithm (GA)-optimized feature selection with Max Voting.

Machine learning approaches for skin cancer diagnosis

Support vector machines (SVMs)

SVMs are known for constructing optimal hyperplanes that maximize the margin between classes. SVMs are particularly effective in handling small datasets and generalizing well, making them suitable for medical image analysis where labeled data is often limited. Studies have shown that SVMs achieve strong performance in binary classification tasks for skin lesions, distinguishing malignant melanoma from benign lesions with high accuracy17,18.

Esteva et al. (2017) demonstrated that SVMs can perform comparably to deep learning models when trained on carefully curated features, making them effective in resource-constrained environments17. Arora et al. (2022) presents a method for skin cancer diagnosis that combines the Bag of Features (BoF) model with a SVM classifier. The BoF model is used to extract distinctive visual features from skin lesion images, such as texture and color patterns, which are then classified using SVM-a powerful algorithm for binary classification18. Such results emphasize that, despite the rise of more complex models, SVMs remain highly relevant for applications where simpler models with fewer data requirements are preferable.

Kalpana et al. (2023) contributes a promising approach for early skin disease diagnosis, emphasizing efficiency, accuracy, and adaptability. By combining SVM and RF in an optimized ensemble, the OESV-KRF model highlights a pathway for developing more effective diagnostic tools that are both powerful and computationally manageable, making it suitable for real-time and resource-limited applications19.

However, SVMs face certain challenges when dealing with large, imbalanced datasets. Specifically, the prevalence of benign cases often overshadows malignant samples, leading to bias in the classification model. To counter this, methods such as Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) have been used alongside SVMs to balance class distributions, improving the detection sensitivity for malignant lesions20. This integration ensures that SVMs can effectively address the imbalance issues. This study incorporates SVMs within an ensemble framework, combining them with RF and MLPN to enhance robustness and accuracy in skin cancer classification.

Random forest (RF)

Random Forest is a commonly utilized ensemble learning technique that integrates multiple decision trees to enhance classification performance and ensure model robustness. A key benefit of RF in medical image analysis is its capacity to process high-dimensional datasets effectively and reduce overfitting by aggregating several weaker models (decision trees). In the context of skin cancer diagnosis, RF has demonstrated high efficacy in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. Mahbod et al. (2019) employed RF in combination with other models to classify melanoma and non-melanoma skin lesions, achieving a comparable accuracy to deep learning models but with reduced computational requirements. RF is especially suitable for datasets where features are highly varied, as it can assess feature importance and optimize decision-making accordingly. Studies have shown that RF performs reliably even with relatively smaller datasets, making it a practical choice in scenarios where large labeled datasets are scarce21.

However, RF models are known to struggle in multi-class classification settings, particularly when classes are imbalanced. As a result, RF is often integrated into ensemble frameworks with other classifiers, such as SVMs or CNNs, to enhance its predictive power in complex classification tasks22. By incorporating RF within an ensemble that leverages a GA for feature selection, this study aims to capitalize on RF’s strengths while addressing its limitations in a multi-class skin lesion classification context.

Multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLPN)

A MLPN is a type of feed-forward neural architecture that is composed of several neuron layers, including input, hidden, and output layers. MLPNs excel at capturing complex, non-linear interactions among features, which makes them particularly useful for medical image analysis where patterns are often intricate23. In skin cancer diagnosis, MLPN has been used both as a standalone classifier and within ensemble frameworks. However, MLPNs often require extensive parameter tuning and sufficient data to achieve optimal performance, which can limit their effectiveness on smaller datasets24. The limitation of MLPNs in handling high-dimensional, imbalanced datasets has led researchers to explore combining MLPN with other ML methods, such as SVM or decision trees, to improve classification accuracy and robustness.

Additionally, MLPNs are prone to overfitting, especially in cases with limited training data. To address this, ensemble methods incorporating MLPN have shown effectiveness in increasing generalizability, particularly when paired with complementary classifiers like RF and SVM. In ensemble methods, such as the one proposed in this study, MLPN can contribute its ability to capture complex feature interactions while being supported by other models like RF and SVM to provide a more generalized solution. By integrating MLPN within an ensemble framework optimized by a GA for feature selection, this study leverages MLPN’s non-linear learning capabilities to enhance overall performance in skin cancer classification.

Ensemble learning in skin cancer classification

Ensemble learning has become a widely adopted approach in skin cancer classification due to its ability to combine the strengths of multiple models, resulting in improved accuracy and robustness. Ensemble methods such as bagging, boosting, stacking, and Max Voting are commonly applied in skin cancer diagnosis, each offering distinct benefits for handling complex image data.

Bagging and random forests Bagging involves training multiple models on different subsets of the data and averaging their predictions. RF, a form of bagging with decision trees as base learners, has been widely used in skin cancer classification. Goyal et al. (2019) demonstrated that RF-based ensemble learning achieved high classification accuracy on melanoma datasets, benefiting from the reduced variance inherent in bagging25. Additionally, Dhivyaa et al. (2020) found that RF models could effectively differentiate between melanoma and benign lesions by capturing complex patterns in dermoscopic images22.

Boosting techniques Boosting combines weak learners sequentially, with each new model focusing on correcting errors made by previous models. Popular boosting algorithms such as AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting have shown promising results in skin cancer classification. For example, Gamil et al. (2024) used AdaBoost to classify dermoscopic images, reporting improvements in sensitivity and specificity by iteratively focusing on difficult cases26. Chang et al. (2022) applied Gradient Boosting in combination with deep features to detect melanoma, achieving high accuracy and specificity, which underscores the potential of boosting methods to enhance classification in medical imaging27. Boosting techniques are particularly effective when dealing with imbalanced datasets, which are common in medical applications where malignant cases are often less frequent.

Stacking ensembles Stacking, or stacked generalization, involves training multiple classifiers and then combining their outputs with a meta-classifier, which learns to make predictions based on the strengths of each base classifier. This technique has been explored in skin cancer diagnosis due to its capacity to leverage multiple model architectures effectively. Shorfuzzaman et al. (2022) developed a stacking ensemble combining CNN models, achieving improved classification performance on skin cancer images28. By incorporating both deep learning and traditional machine learning models, stacking ensembles can capture both high-level patterns and precise boundaries, offering enhanced classification accuracy.

Max Voting and hybrid ensembles Max Voting is one of the simplest ensemble methods, where each classifier “votes” on the predicted class, and the class with the majority of votes is selected. Although straightforward, Max Voting has proven effective in various skin cancer classification studies. Bhowmik et al. (2019) implemented a Max Voting ensemble combining learning models of IG-ResNeXt-101, SWSL-ResNeXt-101, ECA-ResNet-101, and DPN-131 achieving higher accuracy in melanoma detection than any individual model29. Max Voting is often applied in hybrid ensembles, which combine multiple machine learning techniques to improve classification accuracy.

Genetic Algorithm

Feature selection is a critical step, especially when working with high-dimensional image data, as it helps reduce overfitting, enhances model generalization, and improves computational efficiency30,31. In this study, we employ a GA to identify the most relevant subset of features from the dermoscopic images, ensuring optimal model performance. The GA is a bio-inspired optimization technique based on the principles of natural selection and genetics, which efficiently searches the feature space for the best combination of features. The GA operates through a series of evolutionary steps, which involve initializing a population of potential feature subsets (chromosomes), evolving these subsets through selection, crossover, and mutation, and iteratively refining the population until an optimal solution is found.

Feature extraction techniques

Feature extraction plays a critical role in skin cancer image analysis by transforming raw image data into meaningful representations that can be used by machine learning models. Two primary categories of features are commonly extracted from dermoscopic images: color features and texture features32.

Color feature extraction

Color features are essential for distinguishing between different types of skin lesions, as malignant and benign lesions often exhibit varying color patterns. Color histograms and color moments are frequently employed to capture the distribution and intensity of colors within an image33. Color histograms measure the proportion of pixels within predefined color bins, allowing for the identification of dominant colors in a lesion. Meanwhile, color moments-such as the mean, standard deviation, and skewness-provide a summary of the lesion’s color distribution. These color features are typically extracted from different color spaces, such as RGB, HSV, and LAB, to improve the robustness of the analysis34.

Texture feature extraction

Texture features offer additional diagnostic insights by analyzing the surface patterns and irregularities of skin lesions. One of the most common texture analysis techniques is the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), which quantifies the spatial relationships between pixel intensities35. GLCM-based features such as contrast, energy, homogeneity, and entropy are widely used to capture the texture of skin lesions. Texture-based features are critical for distinguishing between benign lesions with smooth surfaces and malignant lesions that tend to exhibit rough, irregular textures36.

While existing ML techniques such as CNNs37, SVMs, and ensemble learning have shown promise in skin cancer diagnosis, they come with several limitations. CNNs, for instance, are highly data-intensive and require large, well-labeled datasets to achieve optimal performance, making them less practical in scenarios where data is scarce or imbalanced. SVMs, though effective in binary classification tasks, struggle with multi-class classification and often require significant tuning of hyperparameters, which can be computationally expensive. Ensemble methods, while improving predictive accuracy through model aggregation, are prone to overfitting, particularly when trained on limited or biased datasets. Additionally, many models do not generalize well across diverse datasets, limiting their applicability in real-world clinical settings. These challenges highlight the need for an approach that not only combines the strengths of multiple models but also optimizes feature selection to enhance generalizability, reduce overfitting, and improve the classification. Our proposed Max Voting ensemble method, paired with a Genetic Algorithm for feature optimization, seeks to address these limitations.

Table 1 offers a concise summary of the reviewed literature, highlighting each method’s contributions and relevance in the context of skin cancer classification.

Challenges and future directions

While existing machine learning techniques such as RFs, SVMs, and ensemble learning have shown promise in skin cancer diagnosis, they come with several limitations. CNNs, for instance, are highly data-intensive and require large, well-labeled datasets to achieve optimal performance, making them less practical in scenarios where data is scarce or imbalanced. SVMs, though effective in binary classification tasks, struggle with multi-class classification and often require significant tuning of hyperparameters, which can be computationally expensive. Ensemble methods, while improving predictive accuracy through model aggregation, are prone to overfitting, particularly when trained on limited or biased datasets. Additionally, many models do not generalize well across diverse datasets, limiting their applicability in real-world clinical settings. These challenges highlight the need for an approach that not only combines the strengths of multiple models but also optimizes feature selection to enhance generalizability, reduce overfitting, and improve the multi-class classification of skin cancer lesions. Our proposed Max Voting ensemble method, paired with a Genetic Algorithm for feature optimization, seeks to address these limitations by offering a more robust and efficient solution for skin cancer diagnosis.

Future research should explore hybrid feature extraction methods that combine deep learning-based features with traditional hand-crafted features. Additionally, there is a need to develop more robust ensemble methods that can handle imbalanced datasets and improve generalization across diverse patient populations.

Proposed method

RF, SVM, and MLPN: ensemble selection rationale

The selection of RF, SVM, and MLPN for the ensemble model is based on the complementary strengths of these models and their proven effectiveness in image classification tasks:

-

1.

Random Forest (RF):

-

Strengths: RF is a resilient ensemble technique that merges several decision trees to mitigate overfitting and enhance model robustness. It is particularly effective in managing high-dimensional datasets and adeptly captures intricate decision boundaries.

-

Rationale: RF is particularly suited for handling noisy data and provides feature importance measures, making it a valuable component for the ensemble. Its capability to generalize well across datasets makes it an excellent choice for classification tasks involving diverse data sources, such as ISIC 2018 and HAM10000.

-

-

2.

Support Vector Machine (SVM):

-

Strengths: SVM is known for its ability to create clear hyperplanes for class separation, making it highly effective for binary and multi-class classification problems. It is robust to overfitting in high-dimensional spaces and performs well with smaller datasets.

-

Rationale: SVM was chosen because of its strong performance in distinguishing between classes with minimal overlap. Its precision in binary classification provides a solid foundation for the Max Voting method, where class boundaries are critical.

-

-

3.

Multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLPN):

-

Strengths: MLPN is a type of feed-forward artificial neural network that excels in capturing non-linear relationships in data. It can learn complex patterns due to its multi-layered structure and activation functions.

-

Rationale: MLPN was selected for its ability to capture intricate patterns in image data that may not be easily identifiable by other models. It complements RF and SVM by learning non-linear dependencies, which adds diversity to the ensemble and enhances overall performance in multi-class classification.

-

By combining RF, SVM, and MLPN in an ensemble, the Max Voting method leverages the strengths of each model while mitigating their individual weaknesses. RF provides robustness against overfitting, SVM delivers precision in class separation, and MLPN captures non-linear patterns, leading to a well-rounded and accurate skin cancer classification system.

GA for optimizing feature selection: rationale

Finding the ideal subset of features that allows precise classification of images with a small number of characteristics is the aim of applying a Genetic Algorithm (GA)38. The selection of the GA for feature selection in this study is driven by several key factors. GA is a robust and well-established optimization technique inspired by the process of natural selection, which makes it highly suitable for solving complex feature selection problems, such as those involving high-dimensional dermoscopic image data. The primary reasons for choosing GA in this study include:

-

1.

Proven Track Record in Feature Selection: GA has been extensively used in feature selection tasks across various domains, including medical image analysis, where it has demonstrated high effectiveness in reducing dimensionality and improving model performance. Its ability to find near-optimal solutions in large search spaces through the processes of selection, crossover, and mutation makes it an ideal candidate for feature selection in complex, high-dimensional datasets like skin lesion images.

-

2.

Balancing Accuracy and Dimensionality Reduction: One of the strengths of GA is its capacity to balance the trade-off between maximizing classification accuracy and minimizing the number of selected features. In this study, GA was used to reduce the original set of 386 features to 72 optimized features without compromising classification accuracy. This reduction helps prevent overfitting and improves model generalization, particularly in highly imbalanced datasets such as HAM10000 and ISIC 2018.

-

3.

Global Search Capability: Unlike greedy algorithms, which may get trapped in local optima, GA performs a global search over the feature space. This ability is critical in feature selection tasks where there are complex inter-dependencies between features. GA’s exploration and exploitation balance allow it to explore various combinations of features, increasing the likelihood of finding the best subset for classification.

Although many advanced metaheuristic algorithms, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), have been used for feature selection, they were not chosen for this study due to specific considerations:

-

1.

Complexity and Computational Cost: Some advanced metaheuristic algorithms, such as Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), are computationally expensive and may require fine-tuning of multiple parameters to perform effectively in high-dimensional feature selection tasks. In contrast, GA’s parameter tuning (e.g., crossover rate, mutation rate) is relatively straightforward, making it more efficient and easier to implement in this context.

-

2.

Effectiveness in Medical Imaging: While algorithms like PSO and ACO have shown success in other domains, GA has a longer history of use in medical image analysis, with demonstrated success in balancing accuracy and dimensionality. GA’s natural selection-inspired approach has proven particularly effective in identifying optimal feature subsets that enhance model performance in medical datasets, making it the preferred choice for this study.

-

3.

Exploration versus Exploitation: While other metaheuristics like PSO emphasize exploration, GA offers a better balance between exploration and exploitation in complex feature spaces. In medical image analysis, where precision is critical, GA’s ability to efficiently exploit the feature space while still exploring new potential feature combinations makes it a better fit for this task.

-

4.

Parameter Sensitivity: Some metaheuristic algorithms are highly sensitive to parameter settings, which can lead to inconsistent performance across different datasets. GA, on the other hand, is relatively robust to parameter variations, allowing for consistent performance improvements without the need for extensive parameter optimization.

GA was selected over other advanced metaheuristic algorithms due to its proven effectiveness in feature selection for medical image analysis, its ability to balance dimensionality reduction with accuracy, and its global search capabilities. While other algorithms have their strengths, GA offers a more efficient, scalable, and reliable approach for selecting optimal features from high-dimensional skin lesion image data in this study.

Max Voting mechanism: rationale

Max Voting aggregates predictions by selecting the class with the majority vote. In this study, it combines predictions from SVM, MLPN, and RF for skin cancer classification. The Key Characteristics of Max Voting:

-

Simplicity: Easy to implement with minimal tuning.

-

Diversity of Models: Uses varied models (SVM, MLPN, RF) to enhance accuracy.

-

Equal Contribution: All models contribute equally to the final decision.

Comparison with other ensemble methods

Max Voting was selected for its simplicity and effectiveness in combining diverse models as shown in the Table 2. Given the goal of robust and reliable skin cancer classification, Max Voting provides a straightforward approach to aggregate predictions from SVM, MLPN, and RF, each contributing its strengths. The simplicity of Max Voting makes it computationally efficient compared to Boosting or Stacking, making it a suitable choice for resource-constrained applications, such as mobile health platforms or clinical decision support systems39,40.

Abstract model perspective of the proposed approach

The main goal of this work is to determine if, in comparison to other models, the suggested Max Voting model can more precisely distinguish between several classifications of skin lesions. The important steps in our proposed method are below:

-

1.

Selection of Dataset: Select a large collection of images of skin lesions covering seven distinct forms of skin cancer. The ISIC 2018 Skin Cancer Datasets41 and HAM10000 were used in this work42.

-

2.

Image Pre processing: Using several preprocessing procedures, improve the quality and analytical value of the raw images.

-

3.

Feature Extraction: Examine the skin images to find and measure significant features that set various lesion types apart.

-

4.

Optimal Feature Subset Selection: Choose the most optimal set of features from the image dataset using a Genetic Algorithm (GA).

-

5.

Pre-trained ML Models: For multi-class skin cancer classification, make use of several pre-trained ML models, such as RF, SVM, and MLPN.

-

6.

Max Voting Method: Using this method, which based the final prediction for each image on the majority vote from the several model predictions, combine the predictions from each model.

-

7.

Performance Evaluation: Using measures like F1-score, accuracy, precision, recall, and confusion matrices, evaluate the models’ performance on the test set.

The suggested model is divided into many stages. Using the suggested Max Voting model, the outputs of these separate pre-trained models are combined to achieve the final classification. Figure 1 shows the workflow diagram.

In-depth analysis of the proposed model

DATASET

To validate the performance of the proposed Max Voting ensemble method, two widely used benchmark datasets-HAM10000 and ISIC 2018-were utilized, which are publicly available43,44. Both datasets are large collections of dermoscopic images of skin lesions, curated to facilitate the development of robust machine learning models for skin cancer classification as shown in the Table 3.

HAM10000 Dataset: The HAM10000 dataset (“Human Against Machine with 10000 Training Images”) is one of the largest public collections of dermoscopic images, containing 10,015 images of pigmented lesions. This dataset covers a broad range of common skin conditions. The dataset provides high-quality dermoscopic images and is labeled with seven different categories of skin lesions. This dataset is highly imbalanced, with a majority of images representing benign conditions (melanocytic nevi). This imbalance poses challenges for machine learning models, as it may bias predictions toward more frequent classes. To address this, data augmentation techniques, including flipping, rotation, and cropping, were employed to balance the distribution of images across lesion types.

ISIC 2018 Dataset: The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) 2018 dataset is another extensive collection of dermoscopic images specifically designed for the ISIC Skin Lesion Analysis Challenges. It contains 13,788 labeled images of various skin lesions. The ISIC 2018 dataset also presents a similar imbalance, with the majority of the images representing benign lesions. However, it provides an excellent challenge for multi-class classification, as it includes both benign and malignant cases, helping researchers develop models capable of early melanoma detection and classification across multiple lesion types.

Data preprocessing and augmentation: Both datasets required preprocessing steps, including resizing images to a uniform size (256 \(\times\) 256 pixels), noise reduction, and contrast enhancement to improve image quality. Data augmentation was applied to increase the number of samples in minority classes, ensuring that models were exposed to more balanced data during training.

Seven different types of skin lesions are included by the HAM10000 and ISIC 2018 datasets: dermatofibroma (df), melanocytic nevi (nv), melanoma (mel), actinic keratosis (akiec), basal cell carcinoma (bcc), benign keratosis (bkl), and vascular lesions (vasc). Figure 2 shows examples of each of these seven kinds. See Table 4 to get a better idea of the distribution of images in these databases. Every class is corresponding to one of the seven image categories of skin cancer. These datasets have an imbalance since the Melanocytic Nevi class has a far larger number of images than the other classes. This problem was solved by equalizing the frequency of images in each class with data augmentation methods45,46. By this procedure, each class had about 3300 images, which produced a more balanced dataset. The performance of several models on the skin lesion dataset was validated during the evaluation phase using this improved dataset.

Image preprocessing

Enhancing image quality and bringing the attention of crucial features required for precise identification require preprocessing skin cancer images. For skin cancer images, the usual preprocessing procedures are as follows.

-

Resizing: This procedure entails resizing an image. The original skin cancer images are in this instance downsized to a standard size of 256 \(\times\) 256 pixels. Maintaining constant image sizes makes tasks like feature extraction and model training easier.

-

Color Space Conversion: When images are converted to grayscale, color information is lost and light intensity is the only consideration. The medical image analysis benefits especially from this conversion since it improves aspects of texture and shape in skin lesions. With pixel values indicating the light intensity from black to white, grayscale images are limited to shades of gray.

-

Contrast Enhancement: This uses methods to increase the contrast in brightness between various areas of an image, therefore enhancing the visibility of its characteristics. Often used for this purpose is histogram equalization. It greatly increases contrast and makes the features within skin lesions more visible from the background by redistributing pixel intensity values to cover the whole grayscale range.

-

Denoising: Images that contain undesired noise-which can be brought on by a variety of things, including environmental circumstances or sensor malfunctions-are denoised. Often used for noise reduction, the median filter replaces each pixel with the median value of the pixels around it.

-

Edge Detection: Finding item boundaries in images requires edge detection. Skin cancer diagnosis depends critically on precise lesion edge description. One often used technique for this is the Canny edge detector.

-

Data Augmentation: This method uses purposely expanding and diversifying the dataset by producing versions of already-existing images. Transforms include rotation, scaling, flipping, and cropping are part of data augmentation.

Feature extraction

Simplifying the extraction and analysis of color-related and textural information is the conversion of RGB images of skin lesions to alternative color spaces47,48 such CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black), HSL (Hue, Saturation, Lightness), XYZ Color Space, and HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value). Correct diagnosis and categorization of the many forms of skin cancer depend on these characteristics. Two basic kinds of features are usually taken out for this reason.

-

1.

Color feature extraction: By figuring out what proportion of pixels belong in each color bin, color histograms show how colors are distributed inside a lesion. With the ability to produce these histograms for every channel in several color spaces (like RGB and HSV), the lesion’s color profile may be fully viewed. Color moments also provide important information on the color properties of the lesion. The mean, sometimes called the first moment, shows the lesion’s main color by averaging the color intensity for each channel. The second moment, sometimes known as the standard deviation, measures color variability and expresses the variety or homogeneity of the distribution. The third moment, skewness, measures the asymmetry of the color distribution and exposes any asymmetrical pigmentation patterns within the lesion. Color histograms were used to quantify the distribution of color across different lesions, and color moments (mean, variance, skewness) were calculated to capture key color characteristics of skin lesions. These features helped differentiate between lesions based on pigmentation and hue variations.

-

2.

Texture feature extraction: The analysis and categorization of skin cancer lesions from images mostly depends on texture features since different benign lesions and skin malignancies have different textual properties49,50,51. The Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM)52 is a sophisticated approach to texture measurement that shows the spatial association between pixel pairs according to their gray-level values. Strong statistical instrument for texture analysis, GLCM measures the spatial correlation between pixel pairs in an image at predetermined directions and distances. Texture features were extracted using the GLCM, which captures spatial relationships between pixel intensities. Features such as contrast, energy, homogeneity, and entropy were computed from the GLCM to distinguish between smooth, benign lesions and rough, malignant ones.

Constructing the GLCM Analysis of pairs of pixels oriented in a certain direction \(e\) and separated by a certain distance \(d\) results in a GLCM. The GLCM obtained for an image with \(g\) gray levels is a \(g \times g\) matrix. This matrix’s \(P(m, n | d, e)\) elements each show how frequently pixel pairs with gray-level values \(m\) and \(n\) occur at the specified distance and direction.

-

1.

Initialization: Start with a zero matrix \(P\) of size \(g \times g\).

-

2.

Pixel Pair Counting: Find a matching pixel in the image for each one that is situated in a given direction \(e\) at a distance \(d\). If \(m\) is the first pixel’s intensity and \(n\) is the second, raise \(P(m, n)\) by one.

-

3.

Normalization: Following the counting of all pertinent pixel pairings, normalize the matrix so that the total of its elements equals 1. Through this transformation, frequency counts become probability values.

$$\begin{aligned} P_{norm}(m, n | d, e) = \frac{P(m, n | d, e)}{ \displaystyle \sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} P(m, n | d,e )}. \end{aligned}$$(1)

Computing texture features from GLCM

After constructing the GLCM, several statistical measures can be extracted to describe the texture of the image:

-

1.

Contrast:.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Contrast} = \sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} (m - n)^2 P_{norm}(m, n | d, e). \end{aligned}$$(2) -

2.

Energy:.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Energy} = \sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} P_{norm}(m, n | d, e)^2 . \end{aligned}$$(3) -

3.

Correlation:

$$\begin{aligned} = \frac{ \displaystyle \sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} (m - \mu _m)(n - \mu _n) P_{norm}(m, n | d, e)}{\sigma _m \sigma _n}. \end{aligned}$$(4)Here, \(\mu _m\) and \(\mu _n\) are the means and \(\sigma _m\) and \(\sigma _n\) are the standard deviations of the row and column sums of the GLCM, respectively.

-

4.

Homogeneity:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Homogeneity}} = \sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} \frac{P_{norm}(m, n | d, e)}{1 + (m - n)^2}. \end{aligned}$$(5) -

5.

Entropy:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Entropy}} = -\sum _{m=0}^{g-1} \sum _{n=0}^{g-1} P_{norm}(m, n | d, e) \log (P_{norm}(m, n | d, e)). \end{aligned}$$(6)The above parameters help to classify the images.

Feature selection optimization-Genetic Algorithm (GA)

The objective of feature selection is to identify the most relevant subset of features that allows accurate classification of images with fewer characteristics. This study applies a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to achieve this goal38. The details of the GA procedure are outlined below, with the specific parameters and values used in this study listed in Table 5.

-

Step 1: Define the GA Components

-

Chromosome Representation: For feature selection tasks, chromosomes are generally represented as binary strings, where each bit corresponds to a feature. A bit value of 1 means the feature is selected, while a value of 0 means it is not.

-

Fitness Function: The fitness function directs the GA in identifying the best subset of features, with the goal of simplifying the model while preserving high classification accuracy.

-

-

Step 2: Initialize Population: Start with an initial, randomly generated set of chromosomes.

-

Step 3: GA Operations

-

Selection: Use tournament selection to pick parent chromosomes for reproduction.

-

Crossover: Perform single-point crossover to create offspring. For instance, if the crossover point is at a specific position, initial features from one parent are combined with the remaining features from the other parent.

-

Mutation: Introduce variation by altering some bits in the offspring based on a certain mutation probability.

-

Replacement: Integrate the newly generated offspring into the population, replacing the chromosomes with the lowest fitness.

-

-

Step 4: Iteration: Repeat the processes of selection, crossover, mutation, and replacement until the fitness score stabilizes or a predefined number of generations is achieved.

-

Step 5: Evaluate the Best Solution: Identify the chromosome with the highest performance based on the optimization function. This chromosome represents the optimal selection of features.

Machine learning models

Random forest (RF)

Using the effective ensemble learning technique RF53,54, several decision trees are built to reduce variance and overfitting in classification problems, hence forming a more accurate and trustworthy model. RF uses the feature matrix that is obtained from the image dataset to accomplish this. Every decision tree is trained using a random subset of the features and data, which lowers overfitting and enhances the generalization capacity of the model. Melanoma, for instance, might be classified by a RF model as highly likely to be malignant based on features like asymmetrical forms and uneven borders. The main RF parameters and the values employed in this study are listed in Table 6.

Support vector machine (SVM)

Classification and regression problems can be addressed with the supervised learning model Support Vector Machine (SVM)55,56. It functions by locating the feature space hyperplane that divides the classes the best. SVM employs One-vs-One (OvO) or One-vs-All (OvA) techniques for multi-class categorization.

A Support Vector Machine’s (SVM) performance for a classification task has to be optimized by carefully evaluating a number of important parameters as shown in Table 7. Low training and testing errors are traded off in the Regularization Parameter (C), where a value of 0.1 indicates a somewhat more tolerant model. The function, such the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, that maps input features into a higher-dimensional space is defined by its Kernel Type. With the One-vs-Rest (OvR) approach defined, the Decision Function Scheme controls how the SVM handles multi-class classification issues. The SVM will penalize misclassifications of the minority class more heavily if the class weight is set to “balanced,” therefore balancing the effects of all classes during the training process. At last, the Random Seed parameter guarantees consistent outcomes throughout several model training sessions. An SVM model’s configuration for best performance depends critically on these factors.

Multi-layer perceptron neural network (MLPN)

Among feed forward artificial neural networks is the multi-layer perception (MLP)57. Each of its several layers of nodes is fully linked to the one before it. MLPs work well for categorizing many classes and can learn complex patterns. The Key parameters of MLPN are listed in Table 8.

Complex categorization problems are particularly well-suited for the feed-forward artificial neural network known as the MLPN. The many layers of nodes that make up its architecture are all fully linked to every node in the layer before it. Since this enables the network to discover complex patterns in the data, it works especially well for multi-class categorization issues.

In order to maximize performance, the MLPNN’s activation function (ReLU), solver (Stochastic Gradient Descent), random state (42), batch size (32), and learning rate initialization (0.01) were all optimized. The general capacity of the model to learn and generalize from the training data is influenced by these factors.

One hundred and fifty neurons make up the first hidden layer, one hundred and fifty in the second. While raising the chance of overfitting, the number of neurons and layers controls the network’s ability to learn from the data. The hidden layers use the widely known Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, which effectively and simply addresses the vanishing gradient issue.

The solution selected affects the speed and efficacy with which the network picks up patterns in the data. Regularization adds a penalty to the loss function for large weights, hence preventing over-fit. A 42-state random state guarantees consistency amongst model training runs.

Skin cancer images can be successfully classified into several groups by the MLPNN with careful adjustment of these parameters.

Max Voting mechanism

The Max Voting (MV) mechanism involves training multiple models on the same dataset. For each input, the predicted class label from each model is used, and MV combines these predictions across all models58. The class with the most votes from all models becomes the final prediction for that input. In cases of a tie, various strategies can be employed, such as random selection, assigning weights based on each model’s confidence, or prioritizing the vote from the most accurate model. The final class label that receives the highest number of votes is termed the “max vote,” which determines the ultimate output prediction. Table 9 outlines the parameters and their respective values for the MV approach implemented in this study.

In an ensemble learning setup, the decision \(V\) for a given input is reached by selecting the class that accumulates the most votes from the ensemble. This decision can be mathematically expressed as follows:

In this formula, \(V\) represents the final decision or output made by the MV method. The \(\arg \max\) function identifies the class index \(m\) that maximizes the expression, ensuring that the selected class label has received the most votes. Here, \(m\) denotes an index representing each class label, ranging from \(L_1\) to \(L_c\), where \(c\) is the total number of unique classes in the dataset. The summation symbol \(\sum\) adds up the votes across all \(N\) models in the ensemble, each contributing one vote per input sample. The indicator function \(1(\cdot )\) returns a value of 1 if the condition within it is true (i.e., if model \(r\) predicts class \(L_m\)), and 0 if it is false. In this context, \(q_r\) denotes the prediction made by the \(r\)-th model for the input sample, while \(L_m\) refers to the \(m\)-th possible class label among the choices available.

Thus, the final decision \(V\) represents the class that the majority of models in the ensemble predict for a given input, reflecting the consensus of the ensemble. When multiple classes receive an equal number of votes, the MV approach applies several strategies to reliably calculate the final decision. One option is weighted voting, where models contribute according to their confidence levels, allowing the class with the highest cumulative weighted score to be selected. Another method is random selection, which guarantees a decision is made by randomly choosing one of the tied classes. Alternatively, the tie can be resolved by relying on the vote from the most accurate model or by prioritizing models based on their historical performance. These approaches help enhance the accuracy and robustness of the classification outcomes. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the ensemble process, illustrating how majority voting and tie-breaking mechanisms contribute to the improved stability and reliability of the MV approach in classification tasks.

Pseudo-code for Max Voting Algorithm:

Input:

-

models: List of pre-trained models [RF, SVM, MLPN].

-

test_data: Dataset to be classified.

-

classes: List of possible class labels (e.g., [Class 0, Class 1, ..., Class N]).

Output:

-

final_predictions: List of predicted class labels for each sample in the test_data.

Steps:

-

1.

Initialize an empty list to store final predictions: final_predictions = []

-

2.

Iterate through each sample in the test data:

for each sample in test_data:

-

Initialize a dictionary to store vote counts for each class:

vote_counts = {class_label: 0 for class_label in classes}

-

For each model, get the predicted class for the current sample:

for each model in models:

predicted_class = model.predict(sample)

-

Increment the vote count for the predicted class:

vote_counts[predicted_class] += 1

-

3.

Find the class with the highest vote count:

max_votes = max(vote_counts.values())

majority_classes = [class_label for class_label, votes in

vote_counts.items() if votes == max_votes]

-

4.

Handle ties (if more than one class has the same vote count):

if len(majority_classes) == 1:

final_class = majority_classes[0]

else:

final_class = tie_break(majority_classes)

-

5.

Append the final class to the final_predictions list:

final_predictions.append(final_class)

-

6.

Return the list of final predictions:

return final_predictions

Function for Tie-Breaking Strategy (optional, depending on use case):

def tie_break(tied_classes):

return random.choice(tied_classes)

The pseudo-code begins by taking three main inputs: a list of trained machine learning models (such as RF, SVM, and MLPN), a dataset containing the samples to be classified, and a list of possible class labels (e.g., melanoma, benign, etc.). The algorithm starts by initializing an empty list called ‘final_predictions‘ to store the final predicted class labels. For each sample in the test dataset, the algorithm iterates through all models in the ensemble to collect predictions, initializing a dictionary called ‘vote_counts‘ to keep track of the votes for each class label. Each model then predicts a class for the sample, and the algorithm increments the corresponding vote count in the ‘vote_counts‘ dictionary.

After collecting votes from all models, the algorithm identifies the class with the highest vote count, also known as the majority vote. If a tie occurs (i.e., multiple classes receive the same number of votes), a tie-breaking strategy is applied. For simplicity, the pseudo-code uses random selection to resolve ties, but other tie-breaking strategies, such as weighted voting or prioritizing the most accurate model, can be implemented. Once the final class label for the sample is determined, it is appended to the ‘final_predictions‘ list. After processing all samples, the algorithm returns the final predictions for the entire test dataset.

Results and its discussion

Experimental setup

Kaggle’s GPU infrastructure supplied the hardware resources for this experiment, which was conducted using Colab and Kaggle as software environments. Three sections-the training set, the test set, and the validation set-were created from the dataset using an 80-10-10 split. More precisely, the training set received 80% of the data, and the test and validation sets each received 10%. The hardware specifications of experimental setup are listed in Table 10.

Features extraction analysis

An in-depth feature analysis was carried out in order to determine the ideal number of characteristics that combine resource efficiency and performance. High performance was to be ensured by this analysis while system efficiency was preserved. Color59,60,61 and texture features62,63,64 were assessed for multi-class categorization to identify changes in skin cancer lesions brought on by malignancy. 386 features in all were initially present, 311 texture features and 75 color features. After gathering data from these features, the features were improved to find the ideal number for every situation, and the results were confirmed using cross-validation.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA) was used to find the optimal feature set size for this multi-class categorization of skin cancer lesions; it was found to be 72 features. Analyzing just the color features at first showed that 31 features had the greatest information gain. Of all the texture features evaluated, 41 showed the most information gain. Combining color and texture data, as Table 11 illustrates, revealed that 72 features in all offered the highest information gain. Using these features in a 10-fold cross-validation procedure produced 94.70% accuracy, 93.23% precision, 92.54% recall, and 94.20% F1-score. The experiment showed that the early stages of skin cancer can be predicted with great accuracy by both color and textural features.

Impact of GA on model performance

The Genetic Algorithm significantly enhanced the performance of the proposed ensemble model by optimizing the feature selection process. Below are the key ways GA improved the overall model:

- Reduction of Feature Dimensionality::

-

From an initial set of 386 features (311 texture features and 75 color features), the GA reduced the feature space to 72 optimal features. This reduction in dimensionality helped simplify the model, making it less prone to overfitting and reducing the computational complexity of training.

- Improved Accuracy and Generalization::

-

By selecting only the most relevant features, the GA ensured that the classification models (RF, SVM, and MLPN) were trained on the most informative data. This led to a substantial improvement in accuracy, with the ensemble model achieving a classification accuracy of 94.70%. The optimized feature set also improved the model’s generalization capabilities, allowing it to perform well on unseen test data. This was particularly important given the highly imbalanced datasets (HAM10000 and ISIC 2018), as the GA selected features that helped the model differentiate between various skin lesion types effectively.

- Prevention of Overfitting::

-

The GA’s ability to balance feature selection and accuracy helped mitigate the risk of overfitting. By reducing the number of unnecessary or redundant features, the GA allowed the model to learn meaningful patterns without memorizing the noise in the data.

The visualizations in Figs. 4, 5 provide insight into how different features both color and texture contribute to the classification accuracy. Color features help distinguish between various pigmentation patterns, while texture features are crucial for identifying structural differences between benign and malignant lesions.

A comparison of model performance before and after feature selection by the GA demonstrates the impact of this optimization process:

As seen in the Table 12, the Genetic Algorithm improved accuracy by over 4%, while significantly reducing the number of features, leading to a more efficient and effective classification model.

Evaluation parameters

To evaluate the performance of a machine learning classification model in predicting categorical labels, many metrics are used65. True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) from the confusion matrix. Various evaluation metrics are calculated from these variables. Below are some popular categorization model evaluation parameters:

-

Confusion Matrix: This table summarizes the classification model’s performance. A detailed breakdown of False Negatives (FN), False Positives (FP), True Positives (TP), and True Negatives (TN) helps assess the model’s performance across classes.

-

Accuracy: This straightforward performance statistic is the percentage of accurately predicted observations to total observations. It works best with balanced target classes.

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Accuracy}} = {\frac{(\text {TP})+(\text {TN})}{\text {TP}+\text {TN}+\text {FP}+\text {FN}}}. \end{aligned}$$(8) -

Precision: Precision is the percentage of accurately expected positive events to all positive predictions the model makes. It facilitates assessing how well the model can reduce false positives.

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Precision}} = {\frac{\text {TP}}{\text {TP}+\text {FP}}}. \end{aligned}$$(9) -

Recall (Sensitivity): Recall (or sensitivity) is the percentage of actual positive cases that the model properly identifies. It facilitates comprehension of how well the model finds every positive case in the dataset.

$$\begin{aligned} {\text {Recall}} = {\frac{\text {TP}}{\text {TP}+\text {FN}}}. \end{aligned}$$(10) -

F1-score: The harmonic average of recall and precision is the F1-score. Recall and precision are both well performed by the model when its F1-score is high. Because it offers a more fair evaluation than accuracy, this statistic is particularly helpful for assessing model performance when dealing with imbalanced classes.

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{F1-score}} = {\frac{2 \times (\text {recall}) \times (\text {precision}) }{\text { recall+precision}}}. \end{aligned}$$(11)

Error analysis and confusion matrix (CM)

A CM provides an extensive tabular performance representation of a classifier66. Using a combined view of prediction results, Fig. 6 distinguishes between correct and erroneous classifications across seven classes. The confusion matrices for six different models are shown.

To show the amount of correct and incorrect predictions for every class, the matrix uses counts. The main goal of it is to illustrate the classification mistakes and misunderstandings that could occur during predictions. In particular, the diagonal cells display the quantity of accurate predictions that correspond to the actual class, whereas the off-diagonal cells indicate misclassifications into other classes. Important observations drawn from Fig. 6 consist of:

-

Diagonal Dominance: A higher number of correct classifications is shown by the diagonal elements in each confusion matrix.

-

Mis classification Patterns: Model-specific misclassification patterns are shown by the off-diagonal parts. Some models, for example, might misclassify particular kinds of lesions more often.

-

Performance Improvement: Performance Enhancement: By lowering misclassifications, the Max Voting method shows better performance and highlights how well ensemble techniques may raise classification accuracy.

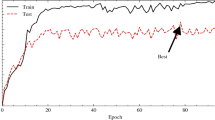

Performance of multiple models on the HAM10000 dataset

The research results and experimental findings of our models on the HAM10000 dataset are presented in this part. With images from this dataset, we evaluated the performance of three machine learning models: RF, SVM, and MLPN. Every model underwent 32 epochs of 64 batch size training. Average accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were among the evaluation parameters. The outcomes of several models tested on the validation dataset, which consists of 1198 images spanning seven different skin lesion types, are compiled in Table 13 following the training procedure. With regard to accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, the suggested Max Voting technique performed better than the other models, as Table 13 demonstrates. Under the Max Voting approach, the performance metrics for every class are listed in Additional Table 14. The results show that Class 1 reported the lowest precision and Class 4 the highest. The bar graph in Fig. 7 illustrates the performance of multiple machine learning models on the HAM10000 dataset.

Performance of multiple models on the ISIC 2018 dataset

In this work, we evaluate and analyze the ISIC 2018 dataset in-depth using different ML models. Models evaluated are MLPN, SVM, and RF. Using average accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score following 32 epochs of training, we assessed their performance. 13,788 dermoscopy images from seven different skin lesion types-melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratoses, benign keratosis-like lesions, dermatofibroma, and vascular lesions-make up the collection. The models were evaluated using a 1,473 image validation dataset following the training phase. The bar graph in Fig. 8 illustrates the performance of multiple machine learning models on the ISIC 2018 dataset.

Results in Table 15 show that ensemble learning model performs noticeably better on the ISIC 2018 dataset when the Max Voting approach is used. With regard to accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, the Max Voting method outperforms individual models such as RF, SVM, and MLPN. Max Voting specifically obtained remarkable overall metrics with a recall of 92.50%, a precision of 93.43%, and an accuracy of 94.12%.

Class-wise analysis, shown in Table 16, shows that, especially for Melanoma and Melanocytic Nevi, the Max Voting approach continuously improves recall and accuracy in identifying various skin lesions. With Melanoma (Class 5) this method produced the highest precision (93.20%) and the best recall (91.70%) for Melanocytic Nevi (Class 4). All things considered, the Max Voting approach shows its effectiveness by raising the accuracy and dependability of skin cancer classification, which makes it an invaluable instrument for early diagnosis and therapy and, eventually, better patient outcomes.

Comparison of state-of-the-art models versus proposed Max Voting model

Numerous elements, such as the dataset, model architecture, and preprocessing methods used, affect the accuracy and performance of machine learning models. Here we give a thorough comparison of our suggested Max Voting model with a number of cutting-edge models that are applied to the categorization of skin cancer. Even if various degrees of success have been shown in recent research, models with greater accuracy and dependability are still needed. The testing accuracy numbers for our suggested methodology are compiled in Table 17 together with those of other methods. As seen, our suggested Max Voting model outperforms the other stated models with an accuracy of 94.70%.

Three models are compared with our Max Voting model: a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) mentioned by Gouda et al.67, a Hybrid CNN put forth by Khan et al.68, and a Max Voting-CNN method by Hossain et al.69. Every one of these models uses different approaches to improve the classification accuracy of skin cancer. Accuracy of the fundamental CNN model was 83.2%. Because CNNs can learn spatial hierarchies, they are useful for image classification tasks; but, when employed alone, they might not be able to properly capture the intricate patterns in skin cancer images. Reaching an accuracy of 84.5%, the Hybrid CNN improves performance by fusing alternative methods with conventional CNNs. Hybrid methods may still find it difficult to manage the variety of skin cancer datasets even when their goal is to take use of the advantages of several techniques. A Max Voting technique integrated into CNNs allowed the Max Voting-CNN model to have a 93.18% accuracy. Predictions from several CNN architectures are combined by the Max Voting technique, which raises accuracy overall. Still, depending only on CNNs can restrict possible benefits. These techniques are surpassed by our suggested Max Voting model, which shows better dependability and higher accuracy in the categorization of skin cancer.

With a Max Voting strategy applied to several pre-trained ML models, our method achieves an astounding accuracy of 94.70%. Using the individual strengths and countering the shortcomings of each model-SVM, RF, and MLPN-this approach successfully integrates predictions from these models. We apply a Genetic Algorithm to choose features as optimally as possible in order to improve the model’s performance even more. Why the Max Voting Ensemble model as described performs better than others is explained by a few factors. First of all, it uses several model kinds to get more thorough information from the dataset. Second, the generalizability of the model is improved and the chance of overfitting is reduced by the ensemble approach. Finally, compared to current techniques for skin cancer classification, the suggested Max Voting Ensemble model is far more precise and trustworthy.

Use of geometric-mean (GM)

The proposed Max Voting ensemble method was evaluated using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. While these metrics are crucial, they may not fully capture the model’s performance on imbalanced datasets such as HAM10000 and ISIC 2018, where benign lesions are more prevalent than malignant ones. To address this, the Geometric Mean (GM) was also computed to provide a balanced evaluation across all classes. The Geometric Mean (GM) is a valuable metric for measuring the balance between sensitivity (recall) and specificity, particularly in imbalanced datasets. It is calculated as the square root of the product of class-wise sensitivities (recalls) and is given by:

where sensitivity for each class is calculated as the proportion of correctly classified instances of that class to the total number of instances of that class.

The Geometric Mean values for each model are shown in Table 18, which highlights the balance achieved by the Max Voting Ensemble.

Comparative analysis

In a comparative analysis, the Max Voting ensemble was bench marked against advanced deep learning models like PyramidNet, YOLOv8, and YOLOv9 in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and GM. While these deep learning models demonstrate high accuracy and fast inference times, the Max Voting ensemble is computationally efficient and easier to interpret, making it more suitable for applications with limited resources.

Table 19 provides a summary of performance results, showing the effectiveness of the Max Voting Ensemble in terms of both accuracy and balanced classification across classes.

The Max Voting Ensemble achieved the highest accuracy (94.70%) and F1-score (94.20%) among all models. The GM score of 91.58% further indicates balanced classification across lesion types, addressing class imbalance more effectively than PyramidNet or YOLO models. The computational simplicity of Max Voting makes it particularly suitable for real-time applications, such as mobile health platforms.

Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA)

A multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) using the Weighted Scoring Model (WSM) was conducted as shown in Table 20 to systematically evaluate model performance across multiple criteria: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, GM, computational cost, and generalization. The criteria and their corresponding weights used for MCDA are presented below:

As shown in the Table 21, each model was then scored on a scale from 1 to 10 for each criterion, and the weighted sum of these scores was calculated for each model. Based on these scores, the models were ranked, with the Max Voting Ensemble achieving the highest score.

The Max Voting ensemble’s top score in MCDA indicates its superior performance in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and overall balance. This makes it an ideal solution for skin cancer classification, especially in real-world applications where computational efficiency is critical.

Incorporating Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) into the model selection process provides a structured and quantitative approach, addressing the need for balanced evaluation across various performance metrics. Future research may explore other MCDA techniques, such as Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) or TOPSIS, to further refine the decision-making process.

Conclusion

In this study, we proposed a Max Voting ensemble method for the multi-class classification of skin cancer lesions, leveraging the combined strengths of Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPN). To enhance model efficiency and accuracy, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) was used for optimal feature selection, significantly reducing dimensionality and improving performance. The method was evaluated on the HAM10000 and ISIC 2018 datasets, achieving a classification accuracy of 94.70%-an improvement over individual models. The key contributions of this study include the development of a Max Voting ensemble that combines predictions from RF, SVM, and MLPN, improving classification accuracy. Additionally, the GA-based optimization of feature selection reduced the number of features and prevented overfitting, leading to better accuracy and model efficiency. Finally, the successful application of the model on real-world datasets demonstrated its robustness in the classification of multiple skin lesion types.

Future work

Future work on this skin cancer classification model could enhance its effectiveness and broaden its applicability in clinical settings. First, combining deep learning-based features, such as those from Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), with traditional color and texture features could create a richer hybrid feature set, potentially leading to improved classification accuracy. Additionally, exploring advanced ensemble techniques beyond Max Voting, such as stacking and boosting methods like Gradient Boosting or AdaBoost, may help increase the model’s robustness and improve its performance on challenging, imbalanced datasets.

Clinical validation is essential for assessing the model’s real-world utility, and collaboration with dermatologists could confirm its reliability in practical medical environments. Real-time deployment is another promising direction; optimizing the model for reduced computational complexity would enable real-time skin cancer screening, particularly in mobile or clinical settings. Addressing class imbalance further, through techniques like synthetic data generation (e.g., GANs) or cost-sensitive learning, could also improve the model’s performance on underrepresented skin lesion types.

Finally, expanding this approach to other medical imaging tasks, such as diagnosing different types of cancer or identifying cardiovascular abnormalities, could reveal its potential in broader healthcare applications. Overall, integrating deep learning, experimenting with additional ensemble methods, and pursuing clinical validation studies will further enhance the model’s accuracy, reliability, and clinical adoption potential.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and confidentiality agreements but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hu, W., Fang, L., Ni, R., Zhang, H. & Pan, G. Changing trends in the disease burden of non-melanoma skin cancer globally from 1990 to 2019 and its predicted level in 25 years. BMC Cancer 22(1), 836 (2022).

Apalla, Z., Nashan, D., Weller, R. B. & Castellsagué, X. Skin cancer: Epidemiology, disease burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. Dermatol. Ther. 7, 5–19 (2017).

Khan, M. Q. et al. Classification of melanoma and nevus in digital images for diagnosis of skin cancer. IEEE Access 7, 90132–90144 (2019).

Zelin, E. et al. Neoadjuvant therapy for non-melanoma skin cancer: Updated therapeutic approaches for basal, squamous, and merkel cell carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 22, 1–24 (2021).

Magnus, K. The Nordic profile of skin cancer incidence. A comparative epidemiological study of the three main types of skin cancer. Int. J. Cancer 47(1), 12–19 (1991).

Venturi, F. et al. Noninvasive diagnostic techniques in the preoperative setting of Mohs micrographic surgery: A review of the literature. Dermatol. Ther. 35(11), e15832 (2022).

Tera, S. P., Chinthaginjala, R., Natha, P., Ahmad, S. & Pau, G. Deep Learning Approach for efficient 5G LDPC Decoding in IoT. IEEE Access (2024).

Karthiga, R., Narasimhan, K., Chinthaginjala, R., Anbazhagan, R., Chinnusamy, M., Pau, G., Satish, K., Amirtharajan, R., & Abbas, M. A novel exploratory hybrid deep neural network to predict breast cancer for mammography based on wavelet features. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–27 (2024).

Renugadevi, M., Narasimhan, K., Ravikumar, C. V., Anbazhagan, R., Pau, G., Ramkumar, K., Abbas, M., Raju, N., Satish, K. & Prabu, S. Machine learning empowered brain tumor segmentation and grading model for lifetime prediction. IEEE Access (2023).

Gupta, A. K., Srinivasulu, A., Oyerinde, O. O., Pau, G. & Ravikumar, C. V. COVID-19 Data analytics using extended convolutional technique. Interdiscipl. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2022(1), 4578838 (2022).

Kumar, N. S. et al. HARNet in deep learning approach—a systematic survey. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8363 (2024).

Bhatt, H., Shah, V., Shah, K., Shah, R. & Shah, M. State-of-the-art machine learning techniques for melanoma skin cancer detection and classification: A comprehensive review. Intell. Med. 3(03), 180–190 (2023).

Goyal, M., Knackstedt, T., Yan, S. & Hassanpour, S. Artificial intelligence-based image classification methods for diagnosis of skin cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Comput. Biol. Med. 127, 104065 (2020).

Raval, D. & Undavia, J. N. A comprehensive assessment of convolutional neural networks for skin and oral cancer detection using medical images. Healthc. Anal. 3, 100199 (2023).

Iqbal, S. N., Qureshi, A., Li, J. & Mahmood, T. On the analyses of medical images using traditional machine learning techniques and convolutional neural networks. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30(5), 3173–233 (2023).

Elgamal, M. Automatic skin cancer images classification. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 4, 3 (2013).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542(7639), 115–118 (2017).

Arora, G., Dubey, A. K., Jaffery, Z. A., & Rocha, A. Bag of feature and support vector machine based early diagnosis of skin cancer. Neural Comput. Appl. 1–8 (2022).

Kalpana, B., Reshmy, A. K., SenthilPandi, S. & Dhanasekaran, S. OESV-KRF: Optimal ensemble support vector kernel random forest based early detection and classification of skin diseases. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 85, 104779 (2023).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Philip Kegelmeyer, W. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Mahbod, A., Schaefer, G., Wang, C., Ecker, R. & Ellinge, I. Skin lesion classification using hybrid deep neural networks. In ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP), 1229–1233. IEEE (2019).