Abstract

In the present scenario, cancerous tumours are common in humans due to major changes in nearby environments. Skin cancer is a considerable disease detected among people. This cancer is the uncontrolled evolution of atypical skin cells. It occurs when DNA injury to skin cells, or a genetic defect, leads to an increase quickly and establishes malignant tumors. However, in rare instances, many types of skin cancer occur from DNA changes tempted by infrared light affecting skin cells. This disease is a worldwide health problem, so an accurate and appropriate diagnosis is needed for efficient treatment. Current developments in medical technology, like smart recognition and analysis utilizing machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques, have transformed the analysis and treatment of these conditions. These approaches will be highly effective for the recognition of skin cancer utilizing biomedical imaging. This study develops a Multi-scale Feature Fusion of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks on Cancerous Tumor Detection and Classification (MFFDCNN-CTDC) model. The main aim of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model is to detect and classify cancerous tumours using biomedical imaging. To eliminate unwanted noise, the MFFDCNN-CTDC method initially utilizes a sobel filter (SF) for the image preprocessing stage. For the segmentation process, Unet3+ is employed, providing precise localization of tumour regions. Next, the MFFDCNN-CTDC model incorporates multi-scale feature fusion by combining ResNet50 and EfficientNet architectures, capitalizing on their complementary strengths in feature extraction from varying depths and scales of the input images. The convolutional autoencoder (CAE) model is utilized for the classification method. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed through a hybrid fireworks whale optimization algorithm (FWWOA) to enhance the classification performance of the CAE model. A wide range of experiments is performed to authorize the performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach. The experimental validation of the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach exhibited a superior accuracy value of 98.78% and 99.02% over existing techniques under ISIC 2017 and HAM10000 datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Melanoma is a critical skin cancer type that seems to be some parts of the skin or adjacent to a mole. The uncontrolled development of the cells is considered skin cancer without some apoptotic. In such a situation, these body part’s cells produce to be cancerous and begin to spread to other body parts1. Unlike the remaining types of skin cancer, melanoma is less prevalent naturally. Nevertheless, melanoma is very dangerous in comparison with the remaining types of skin cancer since it spreads to different parts of the body when absent undiagnosed or untreated in its initial phases. Melanoma spreads quickly through the body and affects nearly every body part2. Dermatologists use microscopic or photographic tools to examine the other information related to lesions. After identifying the cancer, the doctors mention the person to a cancer specialist who carries out surgeries on the lesions3. These models have been used to differentiate benign and malignant lesions depending on the images taken without extracting the skin and other madden check-ups4. These analysis methods rely entirely on the oncologists’ experience and expertise. Such a condition is a struggle for the present research authors to improve a computer-assisted model by using dermoscopic images and showing the results as helping tools for dermatologists5.

Several experiments have been carried out so far to reach better results in disease diagnosis. Melanoma is related to benign moles; hence, it’s not difficult to differentiate benign and malignant regardless of experienced dermatologists6. Various techniques, such as hand-made and artificial intelligence (AI) models, were presented to resolve these difficulties. AI is a subfield of DL and ML. ML constructs a model to detect data and get predictions. DL might study associated image features and remove the features with different structures7. Moreover, DL is very effective for extensive data study. Another DL model is a convolutional neural network (CNN), which has introduced an outstanding performance in image and video processing with the growth of graphics processing unit (GPU) methods8. CNN is an excellent device for bio-image analysis depending on a new investigation. Therefore, it permits a higher potential in the classification of melanoma. Additionally, CNN collective models have exposed achievement for this task of classification. Skin cancer is very general, and initial analysis is essential9. Even though computer-assisted diagnostic devices were widely considered, they were absent in medical training. ML and especially DL techniques have established major promise in skin lesion classification tasks: data availabilities for a few lesion types and the necessity of professionals to annotate and gather the data10. As a result, emerging powerful but well-organized techniques can run in decentralized strategies.

This study develops a Multi-scale Feature Fusion of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks on Cancerous Tumor Detection and Classification (MFFDCNN-CTDC) model. The main aim of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model is to detect and classify cancerous tumours using biomedical imaging. The MFFDCNN-CTDC method initially utilizes a sobel filter (SF) for the image preprocessing stage to eliminate unwanted noise. For the segmentation process, Unet3+ is employed, providing precise localization of tumour regions. Next, the MFFDCNN-CTDC model incorporates multi-scale feature fusion by combining ResNet50 and EfficientNet architectures, capitalizing on their complementary strengths in feature extraction from varying depths and scales of the input images. The convolutional autoencoder (CAE) model is utilized for the classification method. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed through a hybrid fireworks whale optimization algorithm (FWWOA) to enhance the classification performance of the CAE model. A wide range of experiments is conducted to authorize the performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach.

Related works

Himel et al.11 developed a technique for skin cancer detection by vision transformer, an advanced DL structure that has established outstanding performance in different image analysis tasks. Pre-processing methods, like augmentation and normalization, are used to improve the sturdiness and generality of the approach. The vision transformer framework has been adjusted to the skin cancer classification tasks. This method utilizes the self-attention mechanism to take complicated spatial and longer-term dependencies inside the imageries, allowing it to learn related features for precise classifications successfully. Viknesh et al.12 developed a computer-assisted detection method. This work presented dual models to detect skin cancer, concentrating mainly on melanoma tumorous cells with image data. The initial model uses CNNs such as VGG-16, AlexNet, and LeNet techniques. The work additionally examines the relationship between the model’s performance and depth using changing dataset dimensions. The next model utilizes SVM using a defaulting RBF kernel, utilizing feature parameters to classify imageries as normal, malignant, or benign. Midasala et al.13 presented a skin cancer classification algorithm with multi-level feature extraction (MFE)-based AI using unsupervised learning (USL), hereafter represented as MFEUsLNet. Firstly, the provided skin imageries are pre-processed using Bilateral Filtering (BF), which extracts the noise objects from the essential imaging. Next, a renowned USL model called K-means clustering (KMC) has been employed for skin lesion segmentations that might effectively identify the affected skin lesion. Therefore, RDWT and gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) are utilized. Lastly, a recurrent neural networks (RNNs) classifier has been applied to train these multiple-level features and classify several skin cancer categories. The authors14 presented a hybrid deep CNN structure to identify skin cancer by adding dual major heuristics. This consists of MobileNet-V2 and Xception approaches. Data augmentation has been developed to balance the database, and the transfer learning (TL) model is used to resolve the lack of labelled databases. It is identified that the recommended model of using Xception in combination with MobileNet-V2 reaches outstanding performance, mainly in terms of the estimated dataset. In15, a hybrid ensemble learning approach has been developed by incorporating either heterogeneous or homogeneous ensemble learning. The raw unbalanced dataset has trained unique ARTMAP, while another has been trained through the balanced dataset. The heterogeneity was designed with fuzzy min-max (FMM) for the 3rd base method. Eventually, the classification was carried out utilizing the rule-based neuro-fuzzy classification (NEFCLASS) technique.

In16, a new method of incorporating ML and DL models has been presented to solve the difficulties of skin cancer detection. DL approach utilizes sophisticated NNs to remove features from imageries; however, the ML approach handles image features that have been gained after implementing models like Local Binary Pattern Histogram and Contour let Transform. Essential feature extraction is critical for some problems of image classification. Rajendran and Shanmugam17 proposed an Automatic Skin Cancer Detection and Classification method with a Cat Swarm Optimizer with DL (ASCDC-CSODL). The major aim of this technique is to apply the DL approach to classify and recognize skin cancers on dermoscopic imaging. The BF was used for noise removal, and UNet was applied to the segmentation procedure. Furthermore, the ASCDC-CSODL technique uses Mobile Net to extract features. The GRU technique is applied to detect skin cancer. Lastly, the CSO model changes the GRU’s hyperparameter values. In18, a new dual optimization-based DL network was introduced. Firstly, the images are gathered, and the gathered images are pre-processed with an adaptive median filter (AMF). those noiseless imageries are handled in Unet to segment the specific area of the skin lesion. Then, the DO models that hybridize Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO) and Bacterial Foraging Optimizer (BFO) were employed to remove the features. Finally, Deep CNN categorizes dissimilar classes depending on the removed feature. Huo et al.19 propose HiFuse. This multi-scale feature fusion network improves medical image classification by preserving global and local features through an adaptive hierarchical structure and inverted residual MLP. Li et al.20 present a multi-scale feature fusion attention network to extract and fuse high and low-level features, focusing on lesion data through attention and dense sampling, ultimately improving classification. Lin et al.21 introduce a multi-scale, multi-branch network with attention mechanisms for enhanced feature fusion and a joint loss function to optimize image quality and detail. Peng, Yu, and Guo22 present MShNet, a multi-scale network with an "h"-shaped architecture featuring two decoders, enhanced down-sampling, and multi-scale feature fusion for improved segmentation.

Chen et al.23 developed a DL approach using multiscale ultrasound images to improve preoperative diagnosis. Xu et al.24 propose a model, MDFF-Net, a CNN-based network that integrates 1-D and 2-D feature extraction networks, utilizing multi-scale channel shuffling and attention modules, for improved feature fusion and classification to avoid misdiagnosis. Han et al.25 present a Dynamic Multi-Scale CNN (DM-CNN) model across multiple medical domains. Li et al.26 propose a Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network (MSFN) with a novel patch sampling strategy based on image entropy and a self-supervised feature extractor, enhanced by an attention-based global-local fusion network for enhanced survival prediction in WSIs. Alqarafi et al.27 propose Multi-scale GC-T2, an automated skin cancer diagnosis framework using advanced pre-processing, semantic segmentation (AdDNet, HAUNT), M-GCN for feature extraction, and a tri-level fusion module for accurate classification. Wang et al.28 present Breast Classification Fusion Multi-Scale Feature Network (BCMNet). This novel classification method uses data augmentation and integrates VGG16 with CBAM to fuse spatial, channel, and multi-scale features, enhancing the accuracy of breast tumour diagnosis. Liu et al.29 propose a multi-scale fusion gene identification network (MultiGeneNet) method that uses dual feature extractors and a bilinear pooling layer to fuse multi-scale features for a richer, more comprehensive representation. Wu et al.30 present a novel attention-based glioma grading network (AGGN) that utilizes dual-domain attention to highlight key features, multi-branch operations for multi-scale extraction, and a fusion module to integrate low-level and high-level features across modalities. Liang et al.31 propose a Correlation-based Multi-scale Feature Fusion Network (CMFuse) that incorporates CNN and Transformer to capture local and global features at diverse scales, adaptively fusing them for improved classification. Zhang et al.32 introduce MS-Net, a Multi-Scale Feature Pyramid Fusion Network that combines a Multi-Scale Attention Module (MSAM) and Stacked Feature Pyramid Module (SFPM) to dynamically adjust receptive fields and focus attention on target organs by improving relevant features. Parshionikar and Bhattacharyya33 present an optimized multi-scale CapsNet for breast cancer detection, using histopathology and thermal images for preprocessing, feature extraction, segmentation, and classification.

The existing studies use vision transformers for capturing spatial dependencies, CNNs for feature extraction, SVMs for classification, and hybrid methods integrating DL with traditional ML methods like ensemble learning and optimization models. Many approaches also incorporate data augmentation, TL, and noise reduction methods to improve model performance, specifically on limited or unbalanced datasets. Some methodologies utilize multi-scale feature extraction, attention mechanisms, and fusion strategies to capture global and local features for enhanced classification accuracy. While these methods portray promising results, they mostly encounter threats, namely high computational complexity, difficulty in generalizing to diverse datasets, potential overfitting, and the need for large labelled datasets. Furthermore, some methods may face difficulty handling noise, irregular-shaped lesions, and edge cases, which could impact their practical application in clinical settings. Despite enhancements in skin cancer detection using DL, current methods still encounter challenges in handling noisy, unbalanced datasets and varying lesion characteristics, affecting model generalization and accuracy. Moreover, many approaches face computational efficiency and scalability difficulty when applied to real-world clinical settings, underscoring the requirement for more robust, lightweight, and generalizable models.

The proposed method

This paper develops a new MFFDCNN-CTDC model. The foremost intention of the model is to detect and classify cancerous tumors using biomedical imaging. It comprises distinct stages, such as image preprocessing, segmentation, multi-scale feature fusion of feature extraction, CAE-based classification, and hybrid FWWOA-based parameter tuning. Fig. 1 demonstrates the complete workflow of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique.

Stage I: SF-based image preprocessing

The presented MFFDCNN-CTDC method initially applies SF to the image preprocessing stage to eliminate unwanted noise. The SF is an effectual edge recognition mode employed in the analysis of biomedical imaging for cancerous tumour recognition34. Highlighting inclines in intensity emphasizes the limits of tumours, helping radiologists’ picture and identify malignancies. The filter procedures images generate a more robust representation of tumour structure, enabling good differentiation between cancerous and healthy tissues. This model improves the accuracy of automatic diagnostic methods by delivering a high-quality input for further diagnosis. Eventually, the SF plays a substantial role in enhancing early recognition.

Stage II: Unet3+ segmentation

For the segmentation process, Unet3+ is employed, providing precise localization of tumour regions. The Unet3+ structure is an innovative form of the original Unet structure initially intended to segment biomedical images35.

It integrates numerous features, which increase the precision of the semantic segmentation outcomes. The structure contains dual networks: an encoding and a decoding system. The encoding system decreases the spatial sizes utilizing pooling and convolutional (Conv) layers, whereas the decoding system upsamples the decreased feature map utilizing the Conv and upsampling layers. Compared to Unet, an essential feature of Unet3+ denotes the deep connection among the decoding and encoding layers, which unites every succeeding block in the system. This enables the information flow among layers, thus enhancing the semantic segmentation precision. Furthermore, the remaining links have been utilized to connect the indistinct layers in the system to enable data production over various layers, enhancing performance. Both Unet++ and Unet need to investigate sufficient data from full size, resulting in the incapability to identify the location and limit of a tissue. Though every decoding layer in \(Unet3+\) comprises equal and small size feature maps from the encoding and superior measure feature maps from the decoding, this enables coarse- and fine-grained detail semantics to be taken at complete size. Unet3+ makes a lateral output from every decoding phase, which is managed by the truth of the ground. To attain deep observation, the final layer of every decoding phase experiences a simple \(3\text{x}3\) convolution succeeded by a sigmoid function and a bilinear upsampling.

Stage III: multi-scale feature fusion of feature extraction

Next, the MFFDCNN-CTDC model incorporates multi-scale feature fusion by combining ResNet50 and EfficientNet architectures, capitalizing on their complementary strengths in feature extraction from varying depths and scales of the input images. TransUNet utilizes CNN to excerpt restricted multi‐scale features36. Despite that, the Transformer could only input from CNN and later extract global information owing to the huge parameter counts. Primarily, an original resolution and the feature maps attained through the primary dual encoding blocks within the encoder module of CNN were removed correspondingly. Later, a suitable patch size is chosen to separate every feature map and map it to the equivalent number of channels by the convolution layer. The feature maps, after separation, were compressed within the height and width dimensions to create a 2D vector, and the learnable related location information is included in them. Afterwards, the 2D vector with various resolutions was fused and spliced within the number of channel dimension inputs. Eventually, the transformer output is segmented based on the combined order and sizes for restoring an input feature map and performs as the encoder feature map for skip connections. The mathematical equation is described as:

where Conv denotes stride, convolution layer, and kernel are equivalent to the chosen size of the patch, Flatten signifies flattening process, \({Y}_{i}\) denotes a 2D vector, which dimensionally decreased from a 3D tensor in height and width sizes, and Concat denotes merging. Specifically, dual 2D vectors were combined in the particular dimensional (channels). \(Tf\) refers to the Transformer block where an input feature vector of \(Tf\) can execute attention evaluation to attain global information. \({X}_{i}\) denotes the feature mapping extracted from the layer \(i\), \({E}_{pos}\) symbolizes the position parameter after flattening \({X}_{i}\), and \(i\) mentions the \(ith\) layer. \(Y\) denotes the feature vector after the Transformer block.

It creates overall usage of original data, instantly links the original resolution imagery accompanied and extracted from CNN inside the channel dimensions, incorporates local and global information of various levels, and offers rich feature data. However, because the transformer has a huge parameter count, to reduce the number of parameters, only feature vectors were chosen as the skip connection and extracted by CNN.

ResNet50 method

ResNet uses the residual block to resolve the gradient vanishing and degradation tasks presented in common CNN37. The residual block extends the wisdom and improves the system’s efficacy. ResNet has achieved great success in the classifier competition of ImageNet. In ResNet, the residual block executes the residual by adding the residual block input and output. The formulation of the residual function is stated as follows.

whereas \(x\) signifies the input, \(W\) denotes the weight, and \(y\) means the output. ResNet network contains several residual blocks wherever the kernel size is distinctive. The traditional structure of RestNet contains RetNet 18, RestNet 50, and RestNet 101. Features extracted by the ResNet are placed in FC layers to classify images.

EfficientNet model

It is a type of CNN which uses a distinctive scaling method that uniformly measures all dimensions, for example, resolution, width, and depth, implementing complex coefficients. Scaling was a significant concern in the world. Scaling was performed mainly across dimensions: depth, resolution, and width. However, it was observed that scaling primarily does enhance precision, but the precision point penetrates gradually by scaling. On the other hand, typical ConvNets could not perform scaling efficiently. An EfficientNets clarifies such problems of scaling as compound scaling. This method used a Compound Coefficient to scale the system equally over the 3 dimensions.

Stage IV: CAE based classification

The CAE model is exploited for the classification method. This method has been selected over other methods for its efficacy in capturing hierarchical patterns and spatial dependencies essential to data38. Unlike CAEs, CAEs use convolutional layers suitable for managing intricate data structures, specifically images, wherever local associations among pixels are important. This structure enables the CAE to efficiently study significant representations using the feature’s spatial locality.

Regarding several language features, CAEs are adjusted for processing textual data as a sequence of words or characters and using Conv operation through these sequences to efficiently capture semantic and syntactic patterns. This capability adjusts CAEs for machine translation, text creation, or sentiment analysis tasks. Furthermore, CAEs depict strong noise resilience in the processing of audio data. CAEs could denoise signal and excerpt related features even through contextual distortions. This ability is significant for audio classification, development applications, and speech detection.

Additionally, CAEs show scalability to HCI applications in effectively analyzing and handling auditory, visual, or textual inputs. This allows CAEs to assist various HCI tasks, like signal identification from virtual helpers, video streams, or sentiment recognition from speaking gestures. Therefore, the CAE’s capability for controlling the various types of data, scalability, and resilience to noise makes it a robust option for applications challenging strong representation learning and feature extraction.

AE is a self‐supervised learning method containing an encoder and a decoder to extract deep features. This includes neural networks. The AE is an artificial neural network, encompassing a sequentially connected 3‐layer development, precisely the output, input layers, and hidden layers (HL), wherever complete layer functions in a USL system. The AE is often used for the data cluster technique. In contrast, the training process comprises two phases: the encoder, where input data is mapped in the HL, and the decoder, where the input data are recreated from the HL. In the encoder, the method assimilates a flattened depiction or input hidden variable. The decoder, the technique, recreates the objective from the compressed representation.

Assume an unlabelled input dataset \({X}_{n}\), where \(n=\text{1,2},\dots ,N\) and \({x}_{n}\in {R}^{m}\), the two phases are stated as follows:

when \(h(x)\) denotes the encoding vector designed from input vector \(x\), X mentions the decoding. Also, \(g\) and \(f\) symbolize the decoding and encoding functions, \({b}_{1}\) and b, and \({W}_{1}{ and W}_{2}\) denote the decoder’s and encoder’s bias vector and weighted matrix. The difference between the input and output is usually called a reconstruction error. This method tries to decline it in training, for example, to reduce \(||x-\widehat{x}|{|}^{2}\). Stacking various \(AE\) layers is possible, and advantageous high‐level features were achieved with fewer capabilities, such as abstraction and invariance. A low reconstruction of error will be attained, so a greater reduction is computed.

CAE is a type of AE that incorporates a convolution kernel with neural networks. 1D-CAE has a strong reconstruction ability and effectually excerpts deep features within the high‐dimension data.

Convolutional layer: In \(X\in {R}^{L}\), the 1D convolutional layer uses \(K\) Conv kernels \({\omega }_{i}\in {R}^{w}(i=\text{1,2}, \dots , K)\) of width \(w\) to perform the Convolutional function on it, specified in Eq. (6).

Here, \(b\) signifies the bias, \(\odot\) denotes the convolutional computation of the input variable and convolutional kernel, and \(f\) defines the activation function.

Pooling layer: In \(T\in {R}^{KError::0x0000L}\), the extensive use of max pooling induces Eq. (7) succeeding to the pooling technique.

Whereas \(\mathcal{S}\) denotes the stride, \(W\) defines the width of the pooling window, and \({T}_{i}\) signifies the \(ith\) feature tensor. Fig. 2 depicts the structure of CAE.

Stage V: hybrid FWWOA-based parameter tuning

Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed through hybrid FWWOA to enhance the performance of the CAE model.

Whale optimization algorithm (WOA)

Meta‐heuristic models have become prevalent in various applied disciplines in the past few decades39. Numerous models synthetically mimic the biological decentralization groups in nature or the cooperative self-organizing behavioural systems. The hunting model of the humpback whale presented the WOA method. Whales are the biggest mammals on earth, having higher emotions and intelligence. Using sensors, they investigated the humpback whale’s predatory behaviour. Team hunting is a characteristic social behaviour of humpback whales. The small and krill fishes that live close to the water surface of the area constitute the major food for humpback whales. Their innovative manner of predation is recognized as the bubble‐net feeding model. In the process of foraging, the humpback whale initially jumps in about 12 meters, then slowly swims near the water’s surface near a circular or 9‐shaped route and gives spiral bubbles near its prey.

Encircling prey

As stated before, humpback whales surround the prey in a hunting portion. Later, recognizing the whale with the best position for hunting, all remaining whales will update their position depending on this position. To mathematically approach the behaviour of encircling, the subsequent equations are presented

whereas \(t\) represents the present iteration, \({X}_{b}\) signifies the position of whales presently discovered with the optimum hunting position, and \(X\) symbolizes the humpback whale position. \(A\) and \(C\) are controller coefficients. They are computed in the following

Here, \(a\) is linearly reduced from two to \(zero,\) \(and r\) represents a randomly generated vector in \([\text{0,1}]\). Moreover, \(|A|<1\) permits all remaining whales to tactic the whale with the better position presently discovered.

With the 4 equations above, a humpback whale can upgrade its site within the space near the prey in a randomly formed position.

Bubble‐net attacking

In this instance, humpback whales utilize spirals to improve their location. To simulate the humpback whale’s spiral motion initially, it’s essential to compute the distance between the whale and its prey. After that, the distance generates the equation for the whale’s spiral motion. This equation is modelled, as demonstrated.

Now, \(b\) denotes the constant applied to define the dimensions of the spiral shape, \(and l\) refers to the randomly generated number between – l and 1.

Whales swim beside a spiral path while encircling their prey inside a reduction circle. To mathematically mimic this instantaneous behaviour, the study accepts a 50% possibility of selecting between a spiral model and a contraction encircling mechanism to update the whale’s position in the optimization process. A randomly generated number, p, defines the whale’s behaviour and updates its position.

whereas \(p\) represents a randomly generated number in zero and one\(.\)

Search for prey

As stated before, whales hunt in groups. After seeking out prey, humpback whales search at random, depending on every other whale’s position. In the exploration stage, unlike the exploitation stage, the positions of search agents are updated by referencing a randomly selected search agent, rather than the best-performing one discovered so far. This strategy encourages diversity in the search process, allowing the algorithm to explore new areas of the search space. The aim is to avoid premature convergence and increase the chances of finding a global optimum. As a result, the exploration stage helps balance exploration and exploitation in optimization tasks.

whereas \({X}_{r}\) represents the position of a randomly selected whale from the group. In such cases, \(|A|>1\) reason for all remaining whales to be selected randomly from the population and get away from it.

Fireworks algorithm

It is stimulated by the sparking fireworks process that was presented. The position of every firework denotes a possible solution in the promising space. If the fireworks blow up, the sparks will be distributed near it. This procedure has been observed as a search method in the local space. The comprehensive algorithmic process is as demonstrated.

Initialize

Randomly select \(n\) positions in the possible space as the initial position of the search agent, and every search agent signifies a firework,

whereas \({X}_{\text{max}}\) and \({X}_{\text{min}}\) signify the upper and lower bounds correspondingly.

Number of sparks

Calculate the fitness function (FF) of every firework; the spark counts presented by every firework are established by the subsequent equation,

Whereas \(m\) is a parameter controlling the total spark counts produced by all fireworks, \(\xi\) is applied as the smaller constant to prevent zero-division error. As a bound, \({\widehat{s}}_{i}\) are applied to prevent the overcoming fireworks effect with better fitness.

whereas \(a\) and \(b\) are constants.

Explosion amplitude

The amplitude of a firework explosion with better fitness is smaller than that of a firework with worse fitness. The amplitude of the explosion of every firework is as demonstrated,

Here, \(\widehat{A}\) represents the maximal explosion amplitude of each firework.

Gaussian explosion

A unique method of generating sparks, the Gaussian explosion, has been introduced to keep the fireworks diverse. The Gaussian spark’s position at dimension \(k\) is decided by updating and randomly selecting the dimensions of some fireworks; those fireworks are randomly selected also,

whereas \(\sim N(\text{1,1})\).

Positions selection

Finally, for every iteration, \(n\) positions have been selected for the explosion of the following iteration. The firework position with the better fitness might be designated; the residual \(n-1\) positions might be chosen based on the distance between their positions, and so on. For every firework, its distance and selection probability are described in the following.

whereas \(K\) signifies the collection of all the present positions of sparks and fireworks. Based on the dual equations above, the more positions near \({x}_{i}\), the lower the probability it should be selected for the following iteration. This approach guarantees the firework’s diversity.

The hybrid algorithms are frequently comprised of dual algorithms with balancing properties that use their powers and efficiently mitigate individual weaknesses, thus improving the algorithm’s complete performance. The WOA is inclined to be trapped within the local optimum problem, whereas the FWA has outstanding exploration properties. The FWWOA hybrid algorithm has been created to unite the features of both. In the FWWOA, the process of spark generation of the FWA is embedded in the WOA iteration to evade early convergence.

An adaptive equilibrium coefficient has been utilized to balance the exploration with the exploitation,

whereas \(q\) signifies the adaptive equilibrium coefficient, \(t\) denotes the present iteration count, \({\text{and Max}}_{-}iter\) means the maximal amount of iterations. After the location of \({X}_{b}\) changes, \(q\) will upgrade to alter the search tactic.

To ensure the hybrid algorithm searches a substantial potential space and to evade an early local optimum, in the initial phase of iteration, \(q\) is small and upsurges gradually, and the FWA is named various times. To effectively explore the optimum in smaller areas, Q upsurges rapidly in the final phase of iteration. To evade the fact that only the WOA goes in the FWWOA method final iteration, \(q\) is in the intervals of \(0 and 0.9\). When FWA is performed, occasionally, the FWWOA method will instantly perform the succeeding iteration to leave the present local optimizer space without any additional exploitation, consequently lacking the global optimum solution. To resolve this case, the WOA uses the present space at least \(T\) iterations before performing the subsequent FWA. \(k\) is utilized to compute the amount of iterations of the WOA as the final FWA has been performed. The initialization of \(k\) is at the beginning of the FWWOA method. Every time the WOA iteration is implemented, the value of \(k\) upsurges by 1. \(r\) denotes a randomly generated value in the interval of \(zero and one\) if \(r>q\) and \(k>T\), the FWA will be performed at the iteration end, and \(k\) will be reset to \(0\). The FWWOA time complexity is almost \(O\left(\left(2{\text{Max}}_{-}iter+1\right)\cdot n\cdot d\right)\), identified by the size of the group \(n\) and search space dimensions \(d.\)

Fitness selection (FS) is a substantial factor in deploying FWWOA’s efficiency. The hyperparameter range procedure includes the solution-encoded system to measure the competence of the candidate solution. In this manuscript, the FWWOA reflects accuracy as the key standard to project the fitness function. Its invention is mentioned as follows.

Here, \(TP\) and \(FP\) signify the positive values of true and false.

Result analysis and discussion

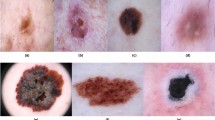

The performance evaluation of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique is verified under the ISIC 201740 and HAM1000041 datasets. The ISIC 2017 dataset comprises 2,357 images of malignant and benign oncological conditions from The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). The images are categorized according to ISIC’s classification system and are evenly dispersed across most subsets, except melanoma and moles, which have a slightly higher representation. The dataset encompasses images of the following conditions: actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, dermatofibroma, melanoma, nevus, pigmented benign keratosis (including seborrheic keratosis), squamous cell carcinoma, and vascular lesions. The HAM10000 dataset contains 10,015 dermatoscopic images of pigmented skin lesions from diverse populations and imaging modalities. It covers categories, namely melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratoses, and vascular lesions, with over 50% confirmed via histopathology. The dataset comprises multiple images per lesion, allowing for tracking by lesion ID. The test set is not public, but analysis can be done through the official challenge server for a fair comparison of methods. A detailed dataset description is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

Figure 4 represents the classification outcomes of the MFFDCNN-CTDC method on the ISIC 2017 database. Figure 4a,b displays the confusion matrix with precise classification and recognition of all 3 class labels under 70%TRAPH and 30%TESPH. Figure 4c exhibits the PR analysis, representing maximal performance across all 3 class labels. Eventually, Fig. 4d shows the ROC analysis, indicating proficient results with greater ROC values for distinctive classes.

Table 2 presents the classification results of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology on the ISIC 2017 dataset. Figure 5 offers the average result of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology on the ISIC 2017 dataset under 70%TRAPH. The outcomes demonstrated that the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique detected and identified all samples. On 70%TRAPH, the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique provides an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.62%, \(sen{s}_{y}\) of 94.37%, \(spe{c}_{y}\) of 97.92%, \({F}_{score}\) of 94.20%, and \(MCC\) of 92.02%.

Figure 6 offers the average result of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model on the ISIC 2017 dataset under 30%TESPH. The outcomes presented that the MFFDCNN-CTDC method detected and identified all samples. On 30%TESPH, the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology offers an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.78%, \(sen{s}_{y}\) of 96.45%, \(spe{c}_{y}\) of 98.93%, \({F}_{score}\) of 96.54%, and \(MCC\) of 95.48%.

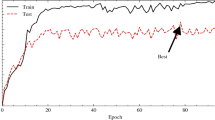

Figure 7 shows the training \(acc{y}_{y}\)(TRAAC) and validation \(acc{u}_{y}\)(VLAAC) outcomes of the MFFDCNN-CTDC method on the ISIC 2017 dataset. The \(acc{u}_{y}\) values are estimated throughout 0-25 epochs. The outcome underlined that the TRAAC and VLAAC values demonstrate a rising tendency, which informed the ability of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique with better performance over several iterations. Besides, the TRAAC and VLAAC remain together over the epochs, which specifies minimal overfitting and exhibits the superior performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique, guaranteeing constant prediction on hidden samples.

Figure 8 shows the TRA loss (TRALS) and VLA loss (VLALS) graphs of the MFFDCNN-CTDC method on the ISIC 2017 dataset. The loss values are estimated for 0-25 epochs. It is denoted that the TRALS and VLALS values show a dropping trend, reporting the ability of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique to balance a trade-off between generalize and data fitting. The continued reduction in loss values also promises the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique’s better efficiency and tunes the prediction results over time.

Figure 9 represents the classification results of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model on the HAM10000 dataset. Figure 9a,b displays the confusion matrix with precise classification and identification of all 7 classes under 70%TRAPH and 30%TESPH. Fig. 9c exhibits the PR analysis, signifying greater performance across all 7 classes. Finally, Fig. 9d depicts the ROC analysis, presenting efficient results with better ROC values for distinctive class labels.

Table 3 and Fig. 10 denote the classifier result of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique on the HAM10000 dataset. The outcomes showed that the MFFDCNN-CTDC model detected and identified all samples. On 70%TRAPH, the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach offers an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.02%, \(sen{s}_{y}\) of 87.86%, \(spe{c}_{y}\) of 99.12%, \({F}_{score}\) of 89.47%, and \(MCC\) of 88.83%. Also, on 30%TESPH, the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique provides an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.89%, \(sen{s}_{y}\) of 86.58%, \(spe{c}_{y}\) of 99.04%, \({F}_{score}\) of 89.05%, and \(MCC\) of 88.33%.

Figure 11 displays the TRAAC and VLAAC outcomes of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique on the HAM10000 dataset. The \(acc{u}_{y}\) values are estimated throughout 0-25 epochs. The outcome underlined that the TRAAC and VLAAC values show a rising tendency, which notified the ability of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model with better performance over several iterations. Also, the TRAAC and VLAAC remain nearer over the epochs, which specifies minimal overfitting and exhibits the superior performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique, guaranteeing continuous forecasts on unseen samples.

Figure 12 shows the TRALS and VLALS graph of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique on the HAM10000 dataset. The loss values are estimated for 0-25 epochs. The TRALS and VLALS values exhibit a lesser tendency, reporting the ability of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology to balance a trade-off between data fitting and generalization. The constant reduction in loss values additionally assures the greater performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology and tunes the prediction outcomes over time.

Table 4 and Fig. 13 examine the comparison results of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology with existing models42,43 on the ISIC 2017 database. The outcomes emphasized that the MAFCNN-SCD, NB, Kernel-ELM, MSVM, MobileNet, and DenseNet169 models have indicated worse performance. Meanwhile, the AMCSCC-WHOEL and Ensemble CNN+SVM methods have yielded closer results. Moreover, the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology indicated enhanced performance with high \(acc{u}_{y}\), \(sen{s}_{y}\), \(spe{c}_{y}\), and \({F}_{score}\) of 98.78%, 96.45%, 98.93%, and 96.54%, respectively.

Table 5 and Fig. 14 study the comparative analysis of the MFFDCNN-CTDC methodology with existing techniques on the HAM10000 database. The outcomes underlined that the MAFCNN-SCD, NB, Kernel-ELM, MSVM, MobileNet, and DenseNet169 approaches have stated worse performance. Meanwhile, the AMCSCC-WHOEL and Ensemble CNN+SVM methodologies have yielded closer results. Besides, the MFFDCNN-CTDC method stated better performance with higher \(acc{u}_{y}\), \(sen{s}_{y}\), \(spe{c}_{y}\), and \({F}_{score}\) of 99.02%, 87.86%, 99.12%, and 89.47%, respectively.

Table 6 and Fig. 15 illustrate the computational time (CT) analysis of the MFFDCNN-CTDC method under the ISIC 2017 dataset. The MFFDCNN-CTDC method achieved the fastest processing time at 4.71 seconds, followed by MobileNet at 7.11 seconds and DenseNet169 at 7.24 seconds. Kernel-ELM took 7.61 seconds, while AMCSCC-WHOEL, Ensemble CNN+SVM, and MAFCNN-SCD methodologies required 8.14, 8.56, and 9.82 seconds, respectively. The NB and MSVM methodologies had slightly longer times at 9.75 and 9.79 seconds.

Table 7 and Fig. 16 portray the CT analysis of the MFFDCNN-CTDC technique under the HAM10000 dataset. The MFFDCNN-CTDC method had the fastest processing time at 6.75 seconds, followed by MobileNet at 11.93 seconds and DenseNet169 at 12.29 seconds. Kernel-ELM took 12.46 seconds, while AMCSCC-WHOEL, Ensemble CNN+SVM, and MAFCNN-SCD required 12.81, 13.60, and 14.64 seconds, respectively. The NB and MSVM models took the longest at 14.71 and 14.75 seconds.

Conclusion

In this study, a novel MFFDCNN-CTDC model is developed. The main intention of the MFFDCNN-CTDC model is to detect and classify cancerous tumours using biomedical imaging. The MFFDCNN-CTDC method initially utilizes SF for image preprocessing to eliminate unwanted noise. For the segmentation process, Unet3+ is employed, providing precise localization of tumour regions. Next, the MFFDCNN-CTDC method incorporates multi-scale feature fusion by combining ResNet50 and EfficientNet architectures, capitalizing on their complementary strengths in feature extraction from varying depths and scales of the input images. The CAE technique is utilized for the classification method. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed using hybrid FWWOA to enhance the classification performance of the CAE method. A wide range of experiments is performed to authorize the performance of the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach. The experimental validation of the MFFDCNN-CTDC approach exhibited a superior accuracy value of 98.78% and 99.02% over existing techniques under ISIC 2017 and HAM10000 datasets.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nodoubttome/skin-cancer9-classesisic and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000.

References

Daghrir, J., Tlig, L., Bouchouicha, M., Sayadi, M. Melanoma skin cancer detection using deep learning and classical machine learning techniques: A hybrid approach. In Proc. of the 2020 5th International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Signal and Image Processing (ATSIP), Sfax, Tunisia, 2–5 September 2020, pp. 1–5 (IEEE, 2020).

Tan, T. Y., Zhang, L. & Lim, C. P. Intelligent skin cancer diagnosis using improved particle swarm optimization and deep learning models. Appl. Soft Comput. 84, 105725 (2019).

Maniraj, S. P. & Maran, P. S. A hybrid deep learning approach for skin cancer diagnosis using subband fusion of 3D wavelets. J. Supercomput. 78, 12394–12409 (2022).

Malibari, A. A. et al. Optimal deep neural network-driven computer aided diagnosis model for skin cancer. Comput. Electr. Eng. 103, 108318 (2022).

Al-Nuaimi, B. T. et al. Adaptive feature selection based on machine learning algorithms for Lung tumors diagnosis and the COVID-19 index. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 11(2), 42–51 (2024).

Barata, C., Celebi, M. E. & Marques, J. S. A survey of feature extraction in dermoscopy image analysis of skin cancer. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 23, 1096–1109 (2019).

Wang, D., Pang, N., Wang, Y. & Zhao, H. Unlabeled skin lesion classification by self-supervised topology clustering network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 66, 102428 (2021).

Ali, M. S., Miah, M. S., Haque, J., Rahman, M. M. & Islam, M. K. An enhanced technique of skin cancer classification using a deep convolutional neural network with transfer learning models. Mach. Learn. Appl. 5, 100036 (2021).

Hasan, M. K., Elahi, M. T. E., Alam, M. A., Jawad, M. T. & Martí, R. DermoExpert: Skin lesion classification using a hybrid convolutional neural network through segmentation, transfer learning, and augmentation. Inform. Med. Unlocked 28, 100819 (2022).

Rahman, Z., Hossain, M. S., Islam, M. R., Hasan, M. M. & Hridhee, R. A. An approach for multiclass skin lesion classification based on ensemble learning. Inform. Med. Unlocked 25, 100659 (2021).

Himel, G. M. S., Islam, M. M., Al-Aff, K. A., Karim, S. I. & Sikder, M. K. U. Skin cancer segmentation and classification using vision transformer for automatic analysis in dermatoscopy-based noninvasive digital system. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2024(1), 3022192 (2024).

Viknesh, C. K., Kumar, P. N., Seetharaman, R. & Anitha, D. Detection and classification of melanoma skin cancer using image processing technique. Diagnostics 13(21), 3313 (2023).

Midasala, V. D. et al. MFEUsLNet: Skin cancer detection and classification using integrated AI with multilevel feature extraction-based unsupervised learning. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 51, 101632 (2024).

Ogundokun, R. O. et al. Enhancing skin cancer detection and classification in dermoscopic images through concatenated MobileNetV2 and xception models. Bioengineering 10(8), 979 (2023).

Mohanty, M. N. & Das, A. Skin cancer detection from dermatoscopic images using hybrid fuzzy ensemble learning model. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 26(1), 260–273 (2024).

Tembhurne, J. V., Hebbar, N., Patil, H. Y. & Diwan, T. Skin cancer detection using ensemble of machine learning and deep learning techniques. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82(18), 27501–27524 (2023).

Rajendran, V. A. & Shanmugam, S. Automated skin cancer detection and classification using cat swarm optimization with a deep learning model. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 14(1), 12734–12739 (2024).

Gomathi, E., Jayasheela, M., Thamarai, M. & Geetha, M. Skin cancer detection using dual optimization-based deep learning network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 84, 104968 (2023).

Huo, X. et al. HiFuse: Hierarchical multi-scale feature fusion network for medical image classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 87, 105534 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Multi-scale high and low feature fusion attention network for intestinal image classification. Signal Image Video Process. 17(6), 2877–2886 (2023).

Lin, C., Chen, Y., Feng, S. & Huang, M. A multibranch and multiscale neural network based on semantic perception for multimodal medical image fusion. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 17609 (2024).

Peng, Y., Yu, D. & Guo, Y. MShNet: Multi-scale feature combined with h-network for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 79, 104167 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. The value of a neural network based on multi-scale feature fusion to ultrasound images for the differentiation in thyroid follicular neoplasms. BMC Med. Imaging 24(1), 74 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. MDFF-Net: A multi-dimensional feature fusion network for breast histopathology image classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 165, 107385 (2023).

Han, Q. et al. DM-CNN: Dynamic multi-scale convolutional neural network with uncertainty quantification for medical image classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 168, 107758 (2024).

Li, L., Liang, Y., Shao, M., Lu, S. & Ouyang, D. Self-supervised learning-based Multi-Scale feature Fusion Network for survival analysis from whole slide images. Comput. Biol. Med. 153, 106482 (2023).

Alqarafi, A., Khan, A. A., Mahendran, R. K., Al-Sarem, M. & Albalwy, F. Multi-scale GC-T2: Automated region of interest assisted skin cancer detection using multi-scale graph convolution and tri-movement based attention mechanism. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 95, 106313 (2024).

Wang, Y., Deng, X., Shao, H. & Jiang, Y. Multi-scale feature fusion for histopathological image categorization in breast cancer. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Vis. 11(6), 2350–2362 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Multi-scale feature fusion for prediction of IDH1 mutations in glioma histopathological images. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 248, 108116 (2024).

Wu, P. et al. AGGN: Attention-based glioma grading network with multi-scale feature extraction and multi-modal information fusion. Comput. Biol. Med. 152, 106457 (2023).

Liang, Z., Lu, H., Zhou, R., Yao, Y. & Zhu, W. CMFuse: Correlation-based multi-scale feature fusion network for the detection of COVID-19 from Chest X-ray images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(16), 49285–49300 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Multi-scale feature pyramid fusion network for medical image segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 18(2), 353–365 (2023).

Parshionikar, S. & Bhattacharyya, D. An enhanced multi-scale deep convolutional orchard capsule neural network for multi-modal breast cancer detection. Healthc. Anal. 5, 100298 (2024).

Aqrawi, A.A. and Boe, T.H. Improved fault segmentation using a dip-guided and modified 3D Sobel filter. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2011, pp. 999-1003 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2011).

Alam, T., Shia, W. C., Hsu, F. R. & Hassan, T. Improving breast cancer detection and diagnosis through semantic segmentation using the Unet3+ deep learning framework. Biomedicines 11(6), 1536 (2023).

He, Y. et al. MultiTrans: Multi-scale feature fusion transformer with transfer learning strategy for multiple organs segmentation of head and neck CT images. Med. Novel Technol. Devices 18, 100235 (2023).

Hilal, A. M. et al. Deep transfer learning-based fusion model for environmental remote sensing image classification model. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 55(sup1), 12–23 (2022).

Akhmetshin, E. et al. Enhancing human computer interaction with coot optimization and deep learning for multi language identification. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 22963 (2024).

Dai, F. & Gao, S. Optimal design of a PIDD2 controller for an AVR system using hybrid whale optimization algorithm. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3454107 (2024).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nodoubttome/skin-cancer9-classesisic

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kmader/skin-cancer-mnist-ham10000

Arumugam, R. V. & Saravanan, S. Automated multi-class skin cancer classification using white shark optimizer with ensemble learning classifier on dermoscopy images. Multimed. Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-18973-8 (2024).

Grignaffini, F. et al. Machine learning approaches for skin cancer classification from dermoscopic images: a systematic review. Algorithms 15(11), 438 (2022).

Acknowledgements

"This study is supported via funding from Prince sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2024/R/1445)". The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by AlMaarefa University while conducting this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prakash U M: Conceptualization, methodology development, experiment, formal analysis, investigation, writing. Iniyan S: Formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing. Ashit Kumar Dutta: Formal analysis, review and editing. Shtwai Alsubai: Methodology, investigation. Janjhyam Venkata Naga Ramesh: Review and editing. Sachi Nandan Mohanty: Discussion, review and editing. Khasim Vali Dudekula: Conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, supervision, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prakash, U.M., Iniyan, S., Dutta, A.K. et al. Multi-scale feature fusion of deep convolutional neural networks on cancerous tumor detection and classification using biomedical images. Sci Rep 15, 1105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84949-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84949-1