Abstract

Oily sensitive skin is complex and requires accurate identification and personalized care. However, the current classification method relies on subjective assessment. This study aimed to classify skin type and subtype using objective biophysical parameters to investigate differences in skin characteristics across anatomical and morphological regions. This study involved 200 Chinese women aged 17–34 years. Noninvasive capture of biophysical measures and image analysis yielded 104 parameters. Key classification parameters were identified through mechanisms and characteristics, with thresholds set via statistical methods. This study identified the optimal ternary value classification method for dividing skin types into dry, neutral, and oily types based on tertiles of biophysical parameters and, further, into barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and inflammatory-sensitive types. Oily sensitive skin shows increased sebum, follicular orifices, redness, dullness, wrinkles, and porphyrins, along with a tendency for oiliness and early acne. Subtypes exhibited specific characteristics: barrier-sensitive skin was rough with a high pH and prone to acne; neurosensitive skin had increased TEWL (Transepidermal Water Loss) and sensitivity; and inflammatory-sensitive skin exhibited a darker tone, with low elasticity and uneven redness. This study established an objective classification system for skin types and subtypes using noninvasive parameters, clarifying the need for care for oily sensitive skin and supporting personalized skincare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In accordance with the Baumann Skin Typing System (BSTI) developed by Leslie Baumann1, skin can be classified into 16 types based on several parameters, including oiliness, dryness, tolerance, sensitivity, hyperpigmentation, wrinkliness, and firmness. Among these types, oily-sensitive (OS) skin is characterized as a composite skin type that exhibits both oily and sensitive traits. Oily sensitive skin is a unique skin type characterized by high sebaceous gland secretion and sensitivity to environmental or physical stimuli1. This skin type is complex due to various underlying mechanisms2,3 that involve physiological and environmental factors, such as sebaceous gland dysfunction, reduced epidermal barrier function, skin microbiome imbalance, inflammatory responses, and neurovascular reactivity4. The interaction of these factors results in diverse clinical manifestations of oily sensitive skin, impacting the psychological and social well-being of individuals5. Therefore, accurate classification and management of oily sensitive skin are crucial challenges in skin science research6.

Recent advances have proposed classifications based on epidermal barrier strength and sensitivity types7,8, such as high, environmental, and cosmetic sensitivities. Additionally, classifications differentiate between primary and secondary sensitive skin based on the presence of related skin disease9. This study focused on the mechanisms and physiological manifestations of skin sensitivity2,10, identifying three subtypes—barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and inflammatory-sensitive skin—each with specific mechanisms11,12,13: barrier damage for the barrier-sensitive subtype, sensory nerve dysfunction for the neurosensitive subtype, and skin inflammation with high vascular reactivity for the inflammatory-sensitive subtype.

Current analyses of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes lack depth, with incomplete indicators and a dearth of objective classification standards. Traditional diagnostics, such as dermatologist visual inspection and patient self-reports, are simple but limited in distinguishing subtypes and severities, particularly for barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and inflammatory-sensitive subtypes, which can be easily confused14. Many noninvasive skin testing instruments have improved, offering new possibilities for objectively assessing oily sensitive skin; however, their application in classification and diagnosis remains limited15. Instruments such as the current perception threshold (CPT) can stimulate nerve fibres related to tactile sensation, pressure, and pain/temperature perception, allowing the measurement of neural sensitivity16. Laser Doppler technology assesses blood flow by monitoring red blood cell movement in the microvasculature, helping to reveal vascular reactivity and the degree of inflammation in oily sensitive skin17. Scientific classification is urgently needed to comprehensively explore oily sensitive skin. The objective of this study was to develop an objective biophysical parameter-based classification system for skin types and subtypes. The aim of this study was to analyse the characteristics of oily-sensitive skin and its subtypes across different anatomical and morphological regions, providing precise guidance for the diagnosis, management, and development of cosmetic products.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study subjects were 200 healthy young female volunteers aged 17–34 years (average age 22 ± 2.89 years), all of whom had resided in Beijing (latitude 39°56’ N, longitude 116°20’ E) for at least one year. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) menstruating, pregnant, or breastfeeding; (b) use of hormonal medications or anti-immunotherapy within 1 month or during the study period; (c) cosmetic surgery, aesthetic treatments, tattooing, maintenance, spotting of moles, facial plastic surgery, or cosmetic needle injections; (d) severe systemic immunodeficiency or autoimmune disease; (d) significant signs of skin irritation, facial injury, swelling, or scarring; (d) cold, headache, or fever on the day of the test; and (d) lack of consent, incomplete information, or participation in other clinical trials. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (protocol code 2017BZHYLL0501). Prior to performing any study-related procedures, all the subjects provided written informed consent. All the experiments were conducted in a room maintained at 21–22 °C with a relative humidity of 45–55%. Before the measurements were taken, all the volunteers were instructed to cleanse their facial skin and then rest quietly for at least 30 min to acclimate to the environment to ensure that their skin fully adapted to the experimental conditions. Our tests are conducted under the supervision of an experienced dermatologist.

Study design

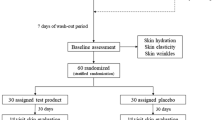

In this study, 104 biophysical facial skin parameters were collected from young Chinese women via noninvasive instruments, and research on the classification and characteristic analysis of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes was conducted (Fig. 1). Skin classification involves three main components: (I) integrating the pathogenesis and physiological traits of sensitive skin to establish key skin classification parameters; (II) performing experiments with different statistical and empirical techniques for skin type categorization, delineating the crucial threshold values of classification indicators; and (III) utilizing the key skin classification parameters to subdivide oily sensitive skin into barrier-sensitive skin, neurosensitive skin, and inflammatory sensitive skin. For the experiments in Step II, the test subjects were classified into six broad categories: oily sensitive skin, oily nonsensitive skin, dry sensitive skin, dry nonsensitive skin, neutral sensitive skin, and neutral nonsensitive skin. They were then subjected tests of water‒oil conditions and sensitivity to compare the efficacy of various classification methods and identify the most suitable classification approach.

Overview of study design. (a) Combining the pathogenesis, after the optimal classification method was selected to classify and analyse the characteristics of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes. (b) Flowchart for skin type classification based on key skin classification parameters. (c) Facial Skin Health Evaluation Parameters Database for skin characteristics analysis.

The analysis of characteristics included two parts: (I) Based on the purpose of the study and the practical significance of the indicators (see S1), the Oily Sensitive Skin Assessment Parameters Set was selected from the Facial Skin Health Evaluation Parameters Database. (II) The apparent characteristics, physiological properties, and pathological conditions of the skin features from four major dimensions (moisture level, colour level, texture level, and perception level) were comprehensively analysed.

Noninvasive biophysical parameter collection

This study preliminarily established the Facial Skin Health Evaluation Parameters Database by collecting 104 noninvasive biophysical parameters to comprehensively assess the physiological state of the skin. The acquisition of noninvasive biophysical parameters was divided into two main parts: physiological parameters (20 items) directly collected by advanced noninvasive skin testing instruments and image parameters (84 items) extracted from the measured images via image processing technology. For details regarding the biophysical parameters, measuring equipment, and test sites, please refer to Table 1A. Most of the samples to directly test physiological parameters were collected from the cheeks via noninvasive skin testing instruments. However, multipoint collection, including from the forehead, canthus, cheek, and jaw, was performed to determine the amount of sebum secretion. The sebum secretion amount indicator used for skin classification was the average value of the forehead and jaw. The sebum secretion indicators used for subsequent differential analysis of sebum secretion in different facial areas were the forehead, canthus, cheek, and jaw.

The specific extraction methods for the indicators obtained through image processing are as follows. The skin image analysis software FrameScan (Orion Company, France) was used to extract wrinkles, spots, red areas, and brightness (oily) indicators, enabling a comprehensive analysis of skin colour and morphology. The comprehensive skin analysis software Image-Pro Plus 7.0 (Media Cybernetics Company, USA) was used to extract follicular orifice indicators. This software was developed by Chinese engineers and integrated with professional image analysis plugins tailored for the cosmetics industry. The porphyrin content was quantitatively assessed via HSV colour model conversion and a fluorescence feature extraction algorithm18. This process included image preprocessing, colour space transformation, and fluorescence feature classification to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the extraction results. The variety and number of acne morphologies were evaluated through manual visual counting in seven areas of the face (① forehead, ② temple, ③ glabella, ④ nose, ⑤ left cheek, ⑥ right cheek, and ⑦ jaw), involving two categories of morphologies with a total of seven types of acne (a, categorized as ① early development, ② ready to burst, and ③ ruptured; b, categorized as ① white head, ② papule, ③ pustule, ④ nodule, and ⑤ cyst). To ensure the accuracy and consistency of labelling, professional students in the cosmetics industry were selected and trained as labellers. A quality control process was implemented to ensure the quality of the labelling.

Selection of the oily sensitive skin assessment parameter set

From the Facial Skin Health Evaluation Parameters Database (Table 1A), the Oily Sensitive Skin Assessment Parameters Set was selected as the primary research indicator for sensitive oily skin (Table 1B). The skin condition of the female Chinese volunteers was measured across four dimensions (moisture, colour, texture, and perception levels), and descriptive statistics were calculated for these skin parameters (Table 1B), enabling a preliminary observation of the data distribution. Correlation analysis was conducted to further examine the relationships among the selected parameters. Heatmap visualization (Fig. 2A) revealed that most skin parameters presented features of oily sensitive skin.

Schematic diagram illustrating image parameter extraction and recognition for screening research indicators and classification methods. (A) Specific extraction areas for parameters of wrinkles, spots, erythema, brightness (oily), follicular orifices and porphyrin content. (B) Acne count involving two categories of morphologies with a total of seven types of acne (a, categorized as ① early development, ② ready to burst, and ③ ruptured; b, categorized as ① whitehead, ② papule, ③ pustule, ④ nodule, and ⑤ cyst). (C) Heatmap visualizing correlations between indicators. (D) Distribution of sample datasets for six skin types across five classification methods. The red boxes and arrows indicate the ternary value division adopted in this study.

Statistical analysis

This study utilized IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 for the statistical analysis. All the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05. For the selection of research indicators, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between parameters. Given the nonparametric distribution of the data, nonparametric test methods were employed to analyse the characteristics of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes. These methods included the Mann‒Whitney U test and Kruskal‒Wallis H test, combined with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, to identify significant differences in skin parameters between different groups. To address the reduction in sample size due to subtype stratification, the bootstrap method was used. This method generates multiple pseudosamples through random sampling with replacement, amplifying the original sample 15-fold to ensure statistically significant results even with smaller subtype sample sizes. Point biserial correlation was used to assess the correlation between skin indicators and different subtypes of oily sensitive skin. Additionally, logistic regression analysis was conducted for different subtypes of oily sensitive skin to quantify skin indicators. Three levels (low, medium, and high) were considered, with binary variables indicating whether the skin type was barrier sensitive, neurosensitive, or inflammatory sensitive. The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

Oily sensitive skin classification

Based on skin physiology, 10 key skin classification parameters were used to classify the skin into dry/oily and sensitive categories. Dry skin is characterized by low CM and sebum secretion19, whereas oily skin has high sebum secretion20. Skin sensitivity is determined by pathophysiological mechanisms2,10, including skin barrier damage, sensory nerve dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and inflammatory responses, as measured by TEWL, pH, CPT at various frequencies, haemoglobin content, a* value, and the red area in Visia images.

Determination of oily sensitive skin types via the ternary value method

We evaluated five skin classification methods and analysed the characteristics of oily sensitive skin. The ternary value classification method demonstrated significant advantages. This method utilizes thresholds based on tertiles of parameters, such as CM, SM, pH, TEWL, CPT, and haemoglobin content (Table 1C). For example, the lowest CM tertile indicates dryness, the lowest SM tertile suggests oil deficiency, and the highest SM tertile indicates oily skin. The participants in the highest SM tertile and lowest CM tertile were categorized as having oily, dehydrated skin. The categories were combined into six major skin categories: oily sensitive, dry sensitive, normal sensitive, normal nonsensitive, oily nonsensitive, and dry nonsensitive skin.

The ternary value method uses comprehensive differential indicators for accurate discrimination. Oily sensitive skin differs significantly from other skin types, allowing clear distinction and identification of unique skin characteristics. Statistical values are more scientific, and a Venn diagram illustrates the overlap and uniqueness among datasets from different methods. The Venn diagram (Fig. 2B) shows consistent skin group delineation across methods, with overlapping areas indicating intersections between datasets. Nonoverlapping parts represent data points uniquely identified by specific methods. The ternary value method’s nonoverlapping region in the Venn diagram, indicating data points not recognized by other methods, is minimal. This finding suggests that its classification is supported by other methods, which increases its credibility and superiority. This method also avoids small sample sizes and expands the subsequent analysis potential.

Therefore, we chose the ternary value classification method as the best approach for further feature analysis. Other methods’ classification processes and data analysis are not detailed here (see S2 for more information).

Identification of three oily sensitive subtypes based on key skin classification parameters

Skin sensitivity is determined based on various pathophysiological mechanisms2,10, including skin barrier damage, dysfunction of cutaneous sensory nerve function, skin vascular reactivity, and inflammatory responses, to classify different subtypes11. The key indicators for the barrier-sensitive type are TEWL and pH, with elevated TEWL and abnormal pH signalling barrier damage11,21,22,23. Sensory nerve dysfunction in neurosensitive skin is evaluated by CPT across varying frequencies16,24. Inflammation-sensitive skin is characterized by vascular reactivity and inflammation, as indicated by a high haemoglobin content and redness of the skin25,26,27,28. Skin redness measured by a colorimeter and Visia images can visually display inflammation29.

Blood perfusion is closely linked to vascular reactivity and inflammatory responses in the pathophysiology of sensitive skin17,27,28,30. Correlation analysis supported the division of sensitive skin based on blood perfusion and sensitive subtype-specific indicators (Table 2C). Blood perfusion correlated significantly with TEWL but not with pH in the barrier-sensitive subgroup (p < 0.05). This finding aligns with the mechanism through which vascular and inflammatory responses can cause vascular dilation, increase blood flow, and impact water loss in the skin31. Changes in pH are more likely related to direct skin barrier damage32. In the neurosensitive subtype, blood perfusion did not correlate significantly with CPT values (p > 0.05), which is consistent with the theory that neurosensitivity is primarily due to nerve ending weakening rather than vascular or inflammatory reactions33,34. In the inflammatory-sensitive subtype, blood perfusion correlated significantly with haemoglobin content, skin redness, and the red area in the Visia images (p < 0.01), highlighting the strong link between inflammatory sensitivity, vascular reactivity, and inflammatory responses.

Sensitive skin subtypes can be differentiated by integrating indicators of skin barrier function, neural sensitivity, and vascular and inflammatory responses. The selection of these indicators is consistent with the mechanisms of skin sensitivity and is corroborated by blood perfusion correlation analysis.

Analysis of oily sensitive skin

This study evaluated skin conditions based on moisture, colour, texture, and perception level. From a comprehensive database of 104 facial skin health parameters, 43 key indicators were selected to analyse oily sensitive skin. The study also compared sebum levels and acne counts in different areas to differentiate oily sensitive skin from other skin types.

Characteristics of oily sensitive skin—features in different dimensions

Descriptive statistics and differential analyses were conducted for different skin parameters (Table 2A-B, Fig. 3A-D). Nineteen parameters significantly differed (p < 0.05) between oily sensitive skin and other skin types, and these differences remained significant for 15 parameters after Bonferroni correction.

Among the moisture level parameters, the SM of oily sensitive skin was high. Oily sensitive skin had significantly greater CM (average = 60.38) and SM (average = 64.96) than sensitive skin. Compared with other skin types, oily sensitive skin has relatively sufficient moisture but excessive SM.

Among the colour level parameters, oily sensitive skin presented increasingly visible red blood vessels and a dark, oily skin tone. Oily sensitive skin had a significantly larger red area (average = 3187.85), significantly greater brightness of the red areas (average = 579.12), significantly greater haemoglobin content (average = 352.09), significantly darker skin tone (ITA°, average = 52.18, p = 0.033), significantly lower brightness (L*, average = 62.98), significantly greater redness (a*, average = 11.36), and significantly greater sebum brightness value (average = 0.004). Compared with other skin types, oily sensitive skin presented greater haemoglobin content, redness, red areas, and brightness, indicating increasingly visible red blood vessels. The skin tone was darker, and the skin brightness was lower with a higher sebum brightness value, indicating a dull but oily skin tone.

Among the texture-level parameters, oily sensitive skin has more pronounced wrinkles, larger follicular orifices, and a higher porphyrin content. Oily sensitive skin exhibited significantly greater roughness (Ra, average = 0.020, p = 0.011), visibility of fine lines around the eyes (average = 16.42, p = 0.018), visibility of perioral lines (average = 30.69, p = 0.025), number of follicular orifices (average = 766.62), follicular orifice area ratio (average = 0.07), and porphyrin content (average = 175.65). Compared with other skin types, oily sensitive skin has a greater follicular orifice area ratio, number of follicular orifices, roughness, and visibility of perioral/ocular fine lines, indicating more visible and denser wrinkles, as well as a greater porphyrin content.

Oily sensitive skin had lower facial nerve sensitivity than sensitive skin. Oily sensitive skin had a significantly lower CPT at 2000 Hz (average = 111.42, p = 0.018), suggesting reduced sensitivity and potentially better tolerance of facial Aβ nerve fibres to touch and pressure stimulation than dry nonsensitive skin.

Characteristics of oily sensitive skin—features of different anatomical sites

The distribution of SM significantly differed among sites with oily sensitive skin (p = 0.003) (Table 3A-C, Fig. 3E-H). In descending order, they were the jaw (average = 50.69), forehead (average = 47.81), eye corners (average = 35.31) and cheeks (average = 31.85). Compared with other skin types, the SM at various sites on oily sensitive skin was significantly greater (p < 0.001).

Differences between oily sensitive skin and other skin types. (A) Comparison of differences in moisture level parameters. (B) Comparison of differences in colour level parameters. (C) Comparison of differences in texture level parameters. (D) Comparison of differences in perception level parameters. (E) Sebum content in different parts of oily sensitive skin. (F) Differences in sebum content in different areas among skin types. (G) Site distribution of sebum content for each skin type. (H) Differences in sebum content by site among skin types. (I) Different sites of acne in oily sensitive skin. (J) Differences in the acne distribution sites of different skin types. (K) Different forms of acne in oily sensitive skin. (L) Differences in acne morphology among skin types.

In terms of acne severity, oily sensitive skin was more likely to present mild to moderate acne. The distribution of acne severity levels among different skin types was compared via the international modified classification method for acne typing35 (Table 3D).

Compared with other skin types, oily sensitive skin tends to have more acne on the forehead, between the eyebrows, and on the right cheek. Oily sensitive skin also had a greater frequency of acne on the forehead, jaw, and cheeks than neutral nonsensitive skin (Table 3E-F). A comparison between oily sensitive skin and neutral nonsensitive skin revealed significant differences in acne frequency on the forehead, between the eyebrows and right cheeks, and overall (p < 0.05). Oily sensitive skin had notably more acne on the forehead (average = 12.69, p = 0.008), between the eyebrows (average = 1.12, p = 0.001), and on the right cheek (average = 3.46, p = 0.037). The distribution of acne within the oily sensitive skin group (Fig. 3I-J) highlights the forehead (average = 12.69), jaw (average = 6.12), left cheek (average = 4.19), and right cheek (average = 3.46) as the main acne sites.

The distribution of acne with different morphologies varies based on skin type. Oily sensitive skin tends to have more nascent and whitehead acne. Acne can be categorized into two types based on morphology: the first type includes early development, ready to burst, and ruptured acne, whereas the second type includes whiteheads, papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. A comparison of acne morphology among different skin types revealed significant differences (Table 3G-H, Fig. 3K), with oily sensitive skin showing more nascent and whitehead acne than other skin types (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3L). Cysts and nodules were not present in the sample. The distribution of acne morphologies within oily sensitive skin samples revealed that nascent acne (average = 24.35, p < 0.05) was more prevalent than burst and ready to burst acne, and whitehead acne (average = 23.50, p < 0.05) was more prevalent than pustules and papules.

Analysis of different subtypes of oily sensitive skin

Overlap of data among subtypes

This study analysed the characteristics of three sensitive oily skin subtypes (barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and inflammatory-sensitive skin) and revealed overlap in their manifestations. Some individuals displayed traits of both barrier-sensitive and inflammatory-sensitive subtypes (Table 4A).

Risk and protective factors for different subtypes

An odds ratio (OR) greater than 1 indicates a risk factor, whereas an OR less than 1 suggests a protective factor. ORs were calculated to evaluate the relationship between skin indicators and the increased or decreased risk of a specific subtype, showing the likelihood of certain characteristics cooccurring in subtypes (Fig. 4A‒C).

This study revealed that a high melanin content (OR = 3.439) and a high percentage of perioral lines (OR = 1.986) were significant risk factors for oily barrier-sensitive skin. Conversely, low cheek SM (OR = 0.420), low sebum brightness (OR = 0.334), moderate forehead pH (OR = 0.258), moderate jaw pH (OR = 0.200), less red area (OR = 0.184), low red area brightness (OR = 0.273), low uniformity (OR = 0.132), low haemoglobin content (OR = 0.185), dark skin colour (OR = 0.267), low roughness Rp (OR = 0.410), low roughness Rz (OR = 0.406), few follicular orifices (OR = 0.311), low follicular orifice area ratio (OR = 0.049), and few acne counts (OR = 0.150) were significant protective factors for oily barrier-sensitive skin.

A low forehead pH (OR = 3.148) was a significant risk factor for oily neurosensitive skin. High CM (OR = 0.208), low TEWL (OR = 0.307), low cheek SM (OR = 0.190), moderate jaw pH (OR = 0.543 compared with low), low melanin content (OR = 0.377), small spot area (OR = 0.485), low redness (OR = 0.464), low visibility of forehead wrinkles (OR = 0.241), low visibility of fine eye lines (OR = 0.400), low percentage of crow’s feet (OR = 0.257), and low percentage of oral furrows (OR = 0.325) were significant protective factors for oily neurosensitive skin.

This study identified several significant risk and protective factors for oily inflammation-sensitive skin. Risk factors included low CM (OR = 4.976), dark skin colour (OR = 4.975), low glossiness (OR = 2.190), low sebum brightness value (OR = 2.190), low elasticity R5 (OR = 2.434), low elasticity R7 (OR = 1.876), a high rate of forehead wrinkles (OR = 2.514), and low visibility of crow’s feet (OR = 2.171). The protective factors included low water dispersion (OR = 0.517), low forehead sebum (OR = 0.426), low melanin content (OR = 0.468), low yellowness b* (OR = 0.256), low roughness Ra (OR = 0.338), a low percentage of brow furrows (OR = 0.383), a low percentage of fine eye lines (OR = 0.332), a low percentage of nasolabial folds (OR = 0.501), and low sensitivity at 250 Hz (OR = 0.444).

Characteristics of different subtypes

A comprehensive analysis revealed distinct differences among oily sensitive skin subtypes across four key dimensions (Table 4B, Fig. 4D-G): moisture (CM, TEWL, SM), colour (haemoglobin, ITA°, a*, b*, glossiness, sebum brightness, red area), texture (elasticity, roughness, wrinkles, follicular orifices, acne), and perception (pH, CPT).

Risk and protective factors for oily sensitive skin subtypes and differences between subtypes. (A) Risk and protective factors for sensitive skin subtypes. (B) Risk and protective factors for oily neurosensitive skin subtypes. (C) Risk and protective factors for oily inflammatory-sensitive skin subtypes. (D) Comparison of differences in moisture level parameters. (E) Comparison of differences in colour level parameters. (F) Comparison of differences in texture level parameters. (G) Comparison of differences in perception level parameters.

The oily barrier-sensitive subtype is characterized by roughness, high pH, large follicular orifices, and frequent acne. This skin type has sufficient CM, less sebum on the forehead, increased haemoglobin, a brighter oily complexion, and reduced neural sensitivity. It appears rough with an overall high pH (approximately 6.4). Common features include large follicular orifices and acne. The forehead wrinkles, brow furrows, and fine lines are less visible, whereas the crow’s feet are more prominent. Brow furrows are extensive, whereas fine eye lines and nasolabial folds are minimal.

The oily neurosensitive subtype is characterized by high TEWL and neural sensitivity. This skin type has low hydration, high water dispersion, excess sebum in specific areas, lower pH levels (approximately 5.8), reduced haemoglobin, lighter skin tone, increased glossiness, and finer skin texture. Nasolabial folds are prominent, whereas crow feet are less visible. Brows and furrows are minimal, and acne is scarce. Additionally, this skin type exhibits heightened facial neural sensitivity.

The oily inflammatory-sensitive subtype is characterized by a dark skin tone, poor glossiness, low elasticity, and uneven redness. It has sufficient hydration, fewer follicular orifices, and a smaller follicular orifice area ratio. The skin tone is dark with high haemoglobin content, high yellowness, low glossiness, and low red area uniformity. The skin lacks elasticity, with visible forehead wrinkles, brow furrows, larger nasolabial folds, and fine eye lines.

Discussion

Development of a classification system for major skin types and oily sensitive subtypes based on objective biophysical parameters

This study used noninvasive skin testing tools and image analysis software to collect detailed skin physiology data from individuals aged 17–34 years. By combining these indicators, a classification system for various skin types and subtypes based on objective biophysical parameters was created, providing a noninvasive method for evaluating skin health within this age group.

The application of noninvasive indicators can improve the objectivity of classification

This study addresses the gap in skin type classification by employing noninvasive, quantifiable biophysical parameters, thereby increasing the precision of sensitive oily skin classification. Favoured for their ease of use and reproducibility, noninvasive tests are valuable for skin physiology research and provide dermatologists with efficient diagnostic methods36,37. These indicators also support the development of customized skincare products38. Our research offers precise guidance for personalized skincare by accurately measuring individual skin parameters to meet consumer needs.

This classification system can more accurately identify OHS

The classification method developed in this study effectively distinguishes different skin subtypes. Points of differentiation from other methods include the following: (I) Our method relies on objective biophysical parameters, unlike subjective methods, such as the skin type indicator (BSTI), which use self-assessment questionnaires. (II) We consider a wider range of physiological skin parameters than other studies, which often focus on only a few parameters. (III) Our method, which uses the ternary value classification approach, focuses on identifying unique skin characteristics that differ from the norm. This method was selected for its high accuracy and reliability in distinguishing oily sensitive skin from other types, unlike the BSTI, which categorizes skin into only two types based on questionnaire scores without considering individual tendencies15. Moreover, the reference values in the manufacturer’s instructions, such as the high reference range for SM, may lead to misclassification of most oily sensitive skin cases as normal skin39,40. (IV) T. Yokota’s research focused on subtype classification based on skin barrier function8. Our study integrated mechanisms of sensitive skin production to propose a detailed subtype classification. Our method considers skin barrier function, neural sensitivity, and vascular reactivity, supporting sensitive skin subtype classification through correlation analysis of blood perfusion parameters to accurately identify and address skin issues.

Comparison of oily sensitive skin characteristics

Biophysical skin parameters significantly differ among populations of different races and from different regions and are influenced by genetic background, diet, climate, environment, and lifestyle choices.

Oily sensitive skin produces excess sebum, especially in the forehead and jaw areas, where sebaceous glands are more concentrated41. Research indicates that oily skin has enlarged follicular orifices, with sebum and follicular orifice sizes increasing significantly after sleep compared with those of nonoily skin42. Studies have linked enlarged follicular orifices to increased sebum production and reduced skin elasticity, leading to more visible wrinkles in oily sensitive skin due to structural damage to the skin tissue43,44. Collagen and elastin, which are essential for skin structure, are affected, contributing to wrinkle formation45.

Additionally, oily sensitive skin with a high porphyrin content may have proinflammatory effects due to the presence of bacterial porphyrins. Elevated porphyrin levels are linked to inflammatory diseases, such as acne vulgaris46. This high porphyrin content can worsen inflammatory responses and contribute to acne development. Acne presentation varies among ethnicities, with studies indicating that women of colour, including African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians, have a greater incidence of acne than Caucasian women. Acne is more prevalent in African American and Hispanic women than in Caucasian, Asian, and Indian women47,48,49. Positive relationships were identified between sebum secretion and acne severity, as well as between follicular orifice size and acne, in African American, Asian, and Indian women.

Acne morphology varies among different ethnicities. Inflammatory acne is more common in Asians, whereas comedonal acne is more prevalent in Caucasians. Facial acne distribution is linked to sebum secretion patterns and daily activities. For example, acne on the forehead, eyebrow, and right cheek acne may be related to sebum secretion and touching habits. The density of hair follicles and sebum secretion levels also influence acne distribution on the forehead, jaw, and cheeks. In Caucasian women, acne affects mainly the cheeks and chin, whereas in non-Caucasian women, it affects primarily the cheeks50. Oily sensitive skin tends to have mild to moderate acne, with severe acne being less common. This finding aligns with previous research findings51,52.

The dullness of the skin tone and redness of oily sensitive skin can be influenced by various factors. High sebum levels in dark skin can worsen dullness due to sebum oxidation and a deepening skin colour53. Postinflammatory pigmentation can also contribute to dull skin tone, especially in African Americans and Hispanics, leading to unwanted pigmentation and scarring49. Asian populations with oily sensitive skin may experience more significant pigment changes than Caucasians, possibly due to genetic differences and UV sensitivity. UV radiation can increase skin pigmentation, with varying effects on different populations. Redness may result from reduced skin barrier function and increased vascular reactivity, allowing irritants to trigger inflammation and vasodilation, causing visible redness.

Studies have shown that healthy skin samples have a relatively high L* value, indicating brighter skin, whereas samples from inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis have a relatively high a* value due to redness, suggesting that inflammation can impact the skin structure and colour. Visual and colorimetric skin assessments can predict structural changes caused by inflammation54.

Comparison of the characteristics of different subtypes of oily sensitive skin

This study identified three oily sensitive skin subtypes, namely, barrier-sensitive, neurosensitive, and, prevalently, inflammatory-sensitive skin, that are potentially related to heightened inflammatory activity55. This study supports the literature indicating that oily individuals are prone to inflammatory sensitivity, possibly due to elevated sebum-induced inflammatory mediator levels. The oily barrier-sensitive and oily neurosensitive subtypes did not overlap, possibly due to their distinct physiological foundations. Oily barrier-sensitive skin is strongly associated with impaired skin barrier function56, whereas oily neurosensitive skin is linked to abnormal neurotransmitter release13.

Overlap was identified between the oily barrier-sensitive and oily inflammatory-sensitive subtypes, as well as between the oily neurosensitive and oily inflammatory-sensitive subtypes, with the latter showing the most significant intersection. Excess sebum secretion in oily sensitive skin makes it prone to inflammatory responses, with sebum components such as free fatty acids potentially activating skin immune cells. This activation can lead to the release of inflammatory mediators, which may trigger neurosensitivity. Compromised skin barriers increase susceptibility to external irritants, leaving nerve endings exposed and intensifying sensations of itching, burning, and tightness12. Overactive release of neurotransmitters, including neuropeptides, can stimulate nerve endings, causing vasodilation and resulting in local congestion, redness, and sensations of heat and stinging57. This vasodilation can further trigger local inflammation, increasing the release of inflammatory mediators and intensifying symptoms such as redness, itching, and burning58,59, establishing a connection between neurosensitivity and inflammatory sensitivity.

Women with the oily barrier-sensitive subtype typically exhibit symptoms such as rough skin, high pH, large follicular orifices, and frequent acne, whereas those with the oily neurosensitive subtype are characterized by high TEWL and heightened neural sensitivity, which is generally consistent with the symptoms of the three subtypes previously categorized based on impaired barrier function8. Women with the oily inflammatory-sensitive subtype display darker skin tone, poor lustre, low elasticity, and uneven redness. This roughness may be due to incomplete skin barrier function, leading to insufficient water retention in the epidermis and resulting in a rough skin surface, which is also consistent with previous research findings60. A relatively high pH can indicate an impaired skin barrier, increasing the vulnerability of the skin to irritation and infection61. The presence of large follicular orifices is usually due to excess sebum secretion, leading to clogged follicular orifices and acne62. Darker skin tone may result from increased melanin production as a defence mechanism against inflammation63. Reduced skin elasticity can be caused by inflammation affecting collagen and elastin structures64.

A high melanin content and a high percentage of perioral lines are risk factors for oily barrier-sensitive skin, which may imply an inadequate ability of the skin to protect against UV radiation, leading to more pronounced pigmentation and signs of ageing. These effects are associated with weakening of the barrier function of the skin65, as increased melanocyte activity may impact the defence of the skin against external stimuli. Studies have shown that UV radiation can damage skin barrier function, trigger skin inflammatory responses66, and result in various signs of photoaging67. Factors such as high water content and low TEWL help maintain the moisture balance of the skin and preserve its barrier function, reducing neurosensitivity. Conversely, low water content and dark skin colour, which are risk factors for oily inflammatory-sensitive skin, may be linked to poor water retention and high UV absorption rates, potentially increasing inflammatory responses. Low lipid, brightness, and SM levels may indicate poor skin health and are associated with inflammatory mediator production and reduced barrier function. Conversely, low melanin content and yellowness, which are protective factors, suggest decreased skin sensitivity to UV radiation and inflammation, reducing inflammatory sensitivity.

Care recommendations for oily sensitive skin and its subtypes

Care recommendations for oily sensitive skin

Compared with other skin types, oily sensitive skin has greater sebum production in all areas, with the forehead and jaw having more oil. Therefore, managing oil levels on the entire face is important, with a focus on regulating sebaceous gland function and reducing oil secretion, especially on the forehead and jaw. Additionally, oil can oxidize on the skin surface, leading to dullness and an oily appearance, which can be addressed by the use of antioxidants to improve skin tone68,69. Excess sebum can combine with keratinocytes and environmental pollutants, causing follicular orifice blockage, acne, inflammation, and skin sensitivity, particularly around the mouth and eyes, increasing susceptibility to wrinkles. Using natural compounds in skincare products can help regulate oil production, increase skin elasticity, and minimize the number of large follicular orifices43,44,62.

Porphyrins are secretions of Citibacterium acnes70 that reside in hair follicles and lead to acne71. High levels of porphyrins in oily sensitive skin may be due to excessive sebum secretion and changes in the microecological environment, providing more nutrients for bacteria such as Citibacterium acnes72,73. These nutrients increase the abundance and activity of bacteria, leading to increased porphyrin production. Controlling oil and improving the microbial barrier can reduce the abundance of Citibacterium acnes. Acne improvement should target al.l areas of the face, focusing on mild (Grade I) and moderate (Grade II) acne, as well as the early development stage and whitehead formation. Oily sensitive skin is prone to sensitive symptoms and inflammation, and anti-inflammatory measures are needed to reduce skin redness74.

In summary, oily sensitive skin requires a comprehensive care strategy to regulate the oil balance, enhance anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capabilities, improve texture, and strengthen the skin barrier. This approach promotes even skin tone, reduces redness, prevents follicular orifice blockage, and addresses ageing concerns such as wrinkles, which improves skin health and resilience against irritants.

Care recommendations for different subtypes of oily sensitive skin

For the various skin issues of the three subtypes, a multidimensional approach can address skin texture, sensation, and colour. Oily barrier-sensitive skin with a rough texture, high pH, large follicular orifices, and acne can be visually improved. Oily neurosensitive skin with high TEWL and neural sensitivity can improve skin sensation. Oily inflammatory-sensitive skin with dullness, poor lustre, low elasticity, and uneven redness can be visually improved in terms of skin colour. Anti-inflammatory measures can improve redness distribution and enhance microcirculation.

Due to overlaps between subtypes and their distinct characteristics, managing oily sensitive skin requires a personalized approach. Cosmetic development should consider these intersections. For individuals with neurosensitive and inflammatory-sensitive subtypes, treatment plans involving reducing inflammation and regulating neurogenic reactions may be necessary. Maintaining skin barrier integrity can reduce inflammatory responses and decrease neurosensitivity risk. Formulations that are anti-inflammatory and neurosoothing could be effective. Educating patients about different subtypes of skin sensitivity can help them understand their conditions and take appropriate care measures. Understanding the overlaps and factors influencing patient subtypes provides a scientific basis for understanding skincare, improving oily sensitive skin conditions, reducing skin problems, and facilitating the development of preventive strategies.

Conclusion

In this study, we created an objective classification system based on biophysical parameters for different skin types and subtypes, specifically within the demographic of Chinese women aged 17–34 years. Using a ternary value classification method, we accurately distinguished oily sensitive skin and its subtypes, providing scientific support for clinical skin care and cosmetic product development. This study utilized multidimensional analysis with various indicators to define the features of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes, facilitating personalized care. The methodology and results establish a foundation for validating and applying this system in various populations, improving our knowledge of oily sensitive skin and its subtypes. However, the sample of this study was limited to Chinese women within a specific age group. As a result, the findings may not be fully applicable to other populations. Future studies should consider expanding the diversity of the sample to increase the generalizability of the results.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baumann, L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann skin type Indicator. Dermatol. Clin. 26, 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2008.03.007 (2008).

Misery, L. et al. Pathophysiology and management of sensitive skin: Position paper from the special interest group on sensitive skin of the International Forum for the study of itch (IFSI). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 34, 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16000 (2020).

Bataille, V., Snieder, H., MacGregor, A. J., Sasieni, P. & Spector, T. D. The influence of genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of acne: a twin study of acne in women. J. Invest. Dermatol. 119, 1317–1322. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19621.x (2002).

Misery, L., Boussetta, S., Nocera, T., Perez-Cullell, N. & Taieb, C. Sensitive skin in Europe. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 23, 376–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03037.x (2009).

Barankin, B. & DeKoven, J. Psychosocial effect of common skin diseases. Can. Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien. 48, 712–716 (2002).

Rita, O., Joana, F. & Filipe, A. L. A. I. An overview of methods to characterize skin type: Focus on Visual Rating scales and Self-Report instruments. Cosmetics 10, 14–14 (2023).

Guerra-Tapia, A., Serra-Baldrich, E., Prieto Cabezas, L., González-Guerra, E. & López-Estebaranz, J. L. Diagnosis and treatment of sensitive skin syndrome: an algorithm for clinical practice. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 110, 800–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2018.10.021 (2019).

Yokota, T., M., M. & S., T. Classification of sensitive skin and development of a treatment System Appropriate for each group. IFSCC 6, 303–307 (2003).

Escalas-Taberner, J., González-Guerra, E. & Guerra-Tapia, A. Sensitive skin: A complex syndrome. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 102, 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2011.04.011 (2011).

Inamadar, A. C. & Palit, A. Sensitive skin: An overview. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 79, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.104664 (2013).

Richters, R. et al. What is sensitive skin? A systematic literature review of objective measurements. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 28, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363149 (2015).

Laverdet, B. et al. Skin innervation: Important roles during normal and pathological cutaneous repair. Histol. Histopathol. 30, 875–892. https://doi.org/10.14670/hh-11-610 (2015).

Yosipovitch, G. et al. Skin barrier damage and itch: Review of mechanisms, topical management and future directions. Acta dermato-venereologica. 99, 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3296 (2019).

Baumann, L. S. The Baumann Skin Typing System. (2010).

Baumann & Leslie. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann skin type Indicator. Dermatol. Clin. 26, 359–373 (2008).

Kim, S. J. et al. The perception threshold measurement can be a useful tool for evaluation of sensitive skin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 30, 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2494.2008.00434.x (2008).

Eun, H. C. Evaluation of skin blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry. Clin. Dermatol. 13, 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-081x(95)00080-y (1995).

Wu, Y., Akimoto, M., Igarashi, H., Shibagaki, Y. & Tanaka, T. Quantitative Assessment of Age-dependent changes in Porphyrins from fluorescence images of Ultraviolet Photography by Image Processing. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 35, 102388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102388 (2021).

Ooi, K. Onset mechanism and Pharmaceutical Management of Dry skin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 44, 1037–1043. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b21-00150 (2021).

de Melo, M. O. & Maia Campos, P. Characterization of oily mature skin by biophysical and skin imaging techniques. Skin. Res. Technology: Official J. Int. Soc. Bioeng. Skin. (ISBS) [and] Int. Soc. Digit. Imaging Skin. (ISDIS) [and] Int. Soc. Skin. Imaging (ISSI). 24, 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.12441 (2018).

Sotoodian, B. & Maibach, H. I. Noninvasive test methods for epidermal barrier function. Clin. Dermatol. 30, 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.08.016 (2012).

Seno, S. I. et al. Quantitative evaluation of skin barrier function using water evaporation time related to transepidermal water loss. Skin research and technology: official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 29, e13242, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.13242

Proksch, E. pH in nature, humans and skin. J. Dermatol. 45, 1044–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14489 (2018).

Kobayashi, H., Kikuchi, K., Tsubono, Y. & Tagami, H. Measurement of electrical current perception threshold of sensory nerves for pruritus in atopic dermatitis patients and normal individuals with various degrees of mild damage to the stratum corneum. Dermatology (Basel Switzerland). 206, 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1159/000068892 (2003).

Pan, Y., Ma, X., Song, Y., Zhao, J. & Yan, S. Questionnaire and Lactic Acid Sting Test Play different role on the Assessment of sensitive skin: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Cosmet. Invest. Dermatology. 14, 1215–1225. https://doi.org/10.2147/ccid.S325166 (2021).

Ding, D. M. et al. Association between lactic acid sting test scores, self-assessed sensitive skin scores and biophysical properties in Chinese females. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 41, 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12550 (2019).

Chen, S. Y. et al. A new discussion of the cutaneous vascular reactivity in sensitive skin: A sub-group of SS? Skin research and technology: official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 24, 432–439, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.12446

Seidenari, S., Francomano, M. & Mantovani, L. Baseline biophysical parameters in subjects with sensitive skin. Contact Dermat. 38, 311–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05764.x (1998).

Xu, D. T., Yan, J. N., Cui, Y. & Liu, W. Quantifying facial skin erythema more precisely by analyzing color channels of the VISIA Red images. J. Cosmet. Laser Therapy: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Laser Dermatology. 18, 296–300. https://doi.org/10.3109/14764172.2016.1157360 (2016).

Issachar, N., Gall, Y., Borrel, M. T. & Poelman, M. C. Correlation between percutaneous penetration of methyl nicotinate and sensitive skin, using laser doppler imaging. Contact Dermat. 39, 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05890.x (1998).

Wu, P. Y. et al. 1,2-Bis[(3-Methoxyphenyl)Methyl]Ethane-1,2-Dicarboxylic acid reduces UVB-Induced Photodamage in Vitro and in vivo. Antioxid. (Basel Switzerland). 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8100452 (2019).

Yosipovitch, G. Dry skin and impairment of barrier function associated with itch - new insights. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 26, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0142-5463.2004.00199.x (2004).

Kawamata, T. et al. Contribution of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 to endothelin-1-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Neuroscience 154, 1067–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.010 (2008).

Li, D. G., Du, H. Y., Gerhard, S., Imke, M. & Liu, W. Inhibition of TRPV1 prevented skin irritancy induced by phenoxyethanol. A preliminary in vitro and in vivo study. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 39, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12340 (2017).

Pochi, P. E. et al. Report of the Consensus Conference on Acne Classification. March 24 and 25, 1990. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 24, 495–500, (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80076-x

Cortés, H. et al. Non-invasive methods for evaluation of skin manifestations in patients with ichthyosis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 312, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-019-01987-w (2020).

Bailey, S. H. et al. The use of non-invasive instruments in characterizing human facial and abdominal skin. Lasers Surg. Med. 44, 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.21147 (2012).

Snyderman, R. & Williams, R. S. Prospective medicine: the next health care transformation. Acad. Medicine: J. Association Am. Med. Colleges. 78, 1079–1084. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200311000-00002 (2003).

Heinrich, U. et al. Multicentre comparison of skin hydration in terms of physical-, physiological- and product-dependent parameters by the capacitive method (corneometer CM 825). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 25, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2003.00172.x (2003).

Youn, S. W., Park, E. S., Lee, D. H., Huh, C. H. & Park, K. C. Does facial sebum excretion really affect the development of acne? Br. J. Dermatol. 153, 919–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06794.x (2005).

Sakuma, T. H. & Maibach, H. I. Oily skin: An overview. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 25, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338978 (2012).

Jo, D. J., Shin, J. Y. & Na, S. J. Evaluation of changes for sebum, skin pore, texture, and redness before and after sleep in oily and nonoily skin. Skin research and technology: official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 28, 851–855, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.13224

Hameed, A., Akhtar, N., Khan, H. M. S. & Asrar, M. Skin sebum and skin elasticity: major influencing factors for facial pores. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 18, 1968–1974. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.12933 (2019).

Kim, B. Y., Choi, J. W., Park, K. C. & Youn, S. W. Sebum, acne, skin elasticity, and gender difference - which is the major influencing factor for facial pores? Skin research and technology: official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 19, e45-53, (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00605.x

Jung, H. J. et al. 2E,5E)-2,5-Bis(3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzylidene) cyclopentanone exerts Anti-melanogenesis and Anti-wrinkle activities in B16F10 Melanoma and Hs27 Fibroblast cells. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23061415 (2018).

Barnard, E. et al. Porphyrin Production and Regulation in Cutaneous Propionibacteria. mSphere 5 https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00793-19 (2020).

Barbieri, J. S., Shin, D. B., Wang, S., Margolis, D. J. & Takeshita, J. Association of Race/Ethnicity and Sex with Differences in Health Care Use and Treatment for Acne. JAMA Dermatol. 156, 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818 (2020).

Gorelick, J. et al. Acne-Related Quality of Life among female adults of different Races/Ethnicities. J. Dermatology Nurses’ Association. 7, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/jdn.0000000000000129 (2015).

Perkins, A. C., Cheng, C. E., Hillebrand, G. G., Miyamoto, K. & Kimball, A. B. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 25, 1054–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03919.x (2011).

Callender, V. D. et al. Racial differences in clinical characteristics, perceptions and behaviors, and psychosocial impact of adult female acne. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 7, 19–31 (2014).

Kaimal, S. & Thappa, D. M. Diet in dermatology: revisited. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 76, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.60540 (2010).

Ghodsi, S. Z., Orawa, H. & Zouboulis, C. C. Prevalence, severity, and severity risk factors of acne in high school pupils: A community-based study. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2136–2141. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2009.47 (2009).

Gunathilake, R. et al. pH-regulated mechanisms account for pigment-type differences in epidermal barrier function. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 1719–1729. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2008.442 (2009).

Dasht Bozorg, B., Bhattaccharjee, S. A., Somayaji, M. R. & Banga, A. K. Topical and transdermal delivery with diseased human skin: passive and iontophoretic delivery of hydrocortisone into psoriatic and eczematous skin. Drug Delivery Translational Res. 12, 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-021-00897-7 (2022).

Barker, J. N., Mitra, R. S., Griffiths, C. E., Dixit, V. M. & Nickoloff, B. J. Keratinocytes as initiators of inflammation. Lancet (London England). 337, 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)92168-2 (1991).

Ananthapadmanabhan, K. P., Moore, D. J., Subramanyan, K., Misra, M. & Meyer, F. Cleansing without compromise: the impact of cleansers on the skin barrier and the technology of mild cleansing. Dermatol. Ther. 17 (Suppl 1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04s1002.x (2004).

Herbert, M. K. & Holzer, P. [Neurogenic inflammation. I. Basic mechanisms, physiology and pharmacology]. Anasthesiologie Intensivmedizin Notfallmedizin Schmerztherapie: AINS. 37, 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32233 (2002).

Jiang, W. C. et al. Cutaneous vessel features of sensitive skin and its underlying functions. Skin research and technology: official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 26, 431–437, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.12819

Sprague, A. H. & Khalil, R. A. Inflammatory cytokines in vascular dysfunction and vascular disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.029 (2009).

Yang, X. X. et al. Facial skin aging stages in Chinese females. Front. Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.870926 (2022).

Park, N. J. et al. Lobelia chinensis Extract and its active compound, Diosmetin, improve atopic dermatitis by reinforcing skin barrier function through SPINK5/LEKTI regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158687 (2022).

Roh, M., Han, M., Kim, D. & Chung, K. Sebum output as a factor contributing to the size of facial pores. Br. J. Dermatol. 155, 890–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07465.x (2006).

Oh, T. I. et al. Plumbagin suppresses α-MSH-Induced Melanogenesis in B16F10 Mouse Melanoma cells by inhibiting tyrosinase activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020320 (2017).

Hussain, Z., Katas, H., Mohd Amin, M. C., Kumolosasi, E. & Sahudin, S. Downregulation of immunological mediators in 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions by hydrocortisone-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 9, 5143–5156. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S71543 (2014).

Wolf, Y. et al. UVB-Induced Tumor Heterogeneity diminishes Immune Response in Melanoma. Cell 179, 219–235e221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.032 (2019).

Farage, M. A., Miller, K. W., Elsner, P. & Maibach, H. I. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in skin ageing: A review. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 30, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2494.2007.00415.x (2008).

Kohl, E., Steinbauer, J., Landthaler, M. & Szeimies, R. M. Skin ageing. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 25, 873–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03963.x (2011).

Huang, H. C., Hsieh, W. Y., Niu, Y. L. & Chang, T. M. Inhibition of melanogenesis and antioxidant properties of Magnolia grandiflora L. flower extract. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-72 (2012).

Park, J. H., Ku, H. J., Lee, J. H. & Park, J. W. IDH2 deficiency accelerates skin pigmentation in mice via enhancing melanogenesis. Redox Biol. 17, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2018.04.008 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Characterization of the human skin resistome and identification of two microbiota cutotypes. Microbiome 9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00995-7 (2021).

Yang, G. et al. Short lipopeptides specifically inhibit the growth of Propionibacterium acnes with a dual antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176, 2321–2335. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14680 (2019).

Zouboulis, C. C. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin. Dermatol. 22, 360–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.004 (2004).

Schommer, N. N. & Gallo, R. L. Structure and function of the human skin microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 21, 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2013.10.001 (2013).

Wong, B. J. & Hollowed, C. G. Current concepts of active vasodilation in human skin. Temp. (Austin Tex). 4, 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/23328940.2016.1200203 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the study participants who provided skin physiological parameters and specimens for the study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Project of the Beijing Educational Committee (KM202010011009) and the Beijing Excellent Talent Training Project-Young Individuals (2018000020124G032), both of which provided funding support to Pr. Fan YI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.K., Y.F., Y.W. and J.G. performed the research. F.Y., K.X., F.Y. and Y.L. designed the research study. Y.C., Y.F., and J.W. contributed essential reagents or tools. X.K., Y.W. and F.Y. analysed the data. X.K.wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (protocol code 2017BZHYLL0501).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuang, X., Lin, C., Fu, Y. et al. A comprehensive classification and analysis of oily sensitive facial skin: a cross-sectional study of young Chinese women. Sci Rep 15, 1633 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85000-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85000-z