Abstract

This study assessed the association between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. The aim was to ascertain the potential of serum α-Klotho levels as a predictive biomarker for hyperlipidemia. The research employed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2013 and 2016. Weighted logistic regression analyses were employed to investigate the association between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were executed for males and females to scrutinize the non-linear correlation between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. Subsequently, piecewise logistic regression analysis was carried out based on the RCS findings. In females, the levels of α-Klotho were notably lower in those with hyperlipidemia in comparison to those without this condition (P < 0.05), No significant variation was demonstrated in α-Klotho levels between males with and without hyperlipidemia (P > 0.05). The participants were stratified by sex and subjected to analysis by logistic regression model. When α-Klotho was log2-transformed, it was significantly negatively associated with the risk of hyperlipidemia in females, even after adjusting for all of the covariates (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.82), which was not observed in males (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.63–2.06). The same results were observed in the third tertile of α-Klotho. Moreover, RCS analysis suggested a nonlinear correlation between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia in females (P < 0.01). The inflection point of α-Klotho was found to be 1106.87 pg/mL. The piecewise logistic regression model revealed that when α-Klotho levels exceeded 1106.87 pg/mL, the link between α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia was no longer significant (P > 0.05). This investigation highlights the sex-based variation in the link between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. In females, α-Klotho exhibited negative association with hyperlipidemia, displaying a saturation effect. Serum α-Klotho emerges as a promising biological marker for the risk of hyperlipidemia among females.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hyperlipidemia, characterized by elevated lipid levels, is a prevalent metabolic disorder with substantial implications for cardiovascular health and mortality1,2,3. Despite the extensive utilization of lipid-lowering medications, the prevalence of hyperlipidemia persists at alarming levels, highlighting the urgent for the exploration of novel therapeutic targets2,3.

Klotho, primarily represented by α-Klotho, alongside β-Klotho and γ-Klotho, is a transmembrane anti-aging protein4. α-Klotho is a type I single-pass transmembrane protein. Its extracellular domain can undergo cleavage by secretory enzymes to enter the bloodstream, urine and cerebrospinal fluid in soluble form5,6. Serum α-Klotho exerts its wide-ranging biological effects on various targets, even several distal organs, functioning as a hormone. The absence of α-Klotho may lead to aging-related symptoms, such as a shortened lifespan, vascular dysfunction, and cognitive impairment7. Conversely, elevated α-Klotho levels have demonstrated the potential to delay aging8. Deficiency or abnormal expression of α-Klotho has been observed in diseases linked to aging, chronic kidney disease (CKD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and osteoporosis. Serum α-Klotho contributes to antioxidant stress, anti-inflammatory responses, ion channel regulation, phosphate homeostasis, glucose metabolism improvement, and insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathways suppression. This indicates that the impact of α-Klotho on aging is probably linked to metabolic regulation. Soluble α-Klotho is negatively associated with body weight and waist circumference9,10, implying its involvement in energy balance regulation. Although α-Klotho inhibits insulin signaling, it can still enhance glucose-induced insulin secretion11 and is negatively linked to blood glucose levels12. Additionally, investigations have indicated that α-Klotho offers protection against adult cardiac metabolic diseases13,14, improving pressure-induced cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling15. Additionally, serum α-Klotho levels are negatively linked to the likelihood of developing CVD13. Klotho provides cardiac protection via inhibiting cardiac oxidative stress16 and attenuating cardiac fibrosis17. Furthermore, α-Klotho helps maintain vascular function by suppressing endothelial cell apoptosis and preventing vascular calcification.

Hyperlipidemia, a known risk factor for CVD, has been reported to be linked to α-Klotho, but findings are inconsistent. Previous investigations have indicated a link between soluble α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia in 40–79 aged people. Specifically, these studies have observed a negative association between α-Klotho and plasma triglyceride (TG) levels18,19,20. Interestingly, in another research, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) demonstrated a favorable association with female α-Klotho and a negative association with male α-Klotho21. Additionally, the negative link between TG and α-Klotho was only noted in females. Hence, the potential link between α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia may also exhibit sex difference, an aspect that has not been reported previously.

The present utilized representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to elucidate the link between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia, particularly across different sexes. The primary objective was to evaluate whether the serum α-Klotho levels could be a predictive biomarker for hyperlipidemia.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The data for this research were sourced from the NHANES, a comprehensive initiative to assess the nutritional and health status of the non-institutionalized civilian population. NHANES utilizes a thorough sampling design, employing a complex, multi-stage, and stratified probability method to assess the prevalence of prevalent health conditions and related risk factors. The NHANES protocol received approval from the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics. Prior to participation, written informed consent was diligently obtained from all enrolled participants. Detailed information regarding NHANES protocols and procedures can be obtained online at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/NHANES.htm.

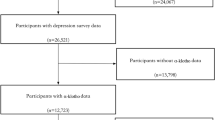

To increase sample size and mitigate potential sampling errors, this investigation combined data spanning NHANES cycles from 2013 to 201622. An initial cohort of 20,146 participants was enrolled in NHANES from 2013 to 2016. Rigorous application of exclusion and inclusion criteria meticulously narrowed down the study cohort to 1400 participants, a process systematically depicted in Fig. 1. Because α-Klotho concentration was assessed exclusively within the 40 to 79 age range, the study initially excluded individuals who were either under 40 years of age or above 79. Initially, participants with incomplete data on exposure and outcome variables were removed from the analysis. Subsequently, individuals lacking covariates data and those without recorded weights were also excluded to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the study’s findings. The weight selected for this study was wtsaf2yr.lipid, and utilizing sampling weights in all statistical analyses was paramount to ensuring the national representativeness of the research outcomes.

Quantification of serum α-Klotho level

The analyses were executed utilizing a commercial ELISA kit manufactured by IBL International (Japan). Before analysis, all samples were kept at − 80 °C. The assay sensitivity of the ELISA kit was found to be 6 pg/mL. Guidelines provided by NHANES were followed and discussed for further details on laboratory methodology, quality assurance, and monitoring.

Hyperlipidemia

The hyperlipidemia status of participants was assessed following the criteria outlined by the National Cholesterol Education Program. Hyperlipidemia was operationally characterized based on specific thresholds, including total cholesterol (TC) levels ≥ 200 mg/dL, TG levels ≥ 150 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels ≥ 130 mg/dL, or female HDL levels ≤ 50 mg/dL, and male HDL levels ≤ 40 mg/dL23. Participants who self-reported the use of lipid-lowering medications were also grouped under the hyperlipidemia category24,25. The presence of hyperlipidemia was established if any one of these five criteria was met, providing a comprehensive and clinically relevant approach to identifying individuals with lipid metabolism disorders.

In order to understand the association between α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia, we classified hyperlipidemia according to the levels of hyperlipidemia components. LDL levels ≥ 130 mg/dL were defined as hyper-LDL, female HDL levels ≤ 50 mg/dL and male HDL levels ≤ 40 mg/dL were defined as hypo-HDL, TG levels ≥ 150 mg/dL were defined as hyper_TG, TC levels ≥ 200 mg/dL were defined as hyper_TC.

Covariates

This investigation comprehensively examined various covariates including demographic, lifestyle-related and health-related factors, through interviews, laboratory tests and physical examinations. Demographic variables comprised age, sex, race, economic status, education level, and marital status, with race was categorized into four groups: Black, White, Mexican, or Other. Moreover, levels of education were stratified into three tiers: less than high school, high school, and college (encompassing individuals with a college degree or higher). Similarly, economic status was evaluated by the family monthly poverty level index, delineated as low (< 1.30), medium (1.30–3.50), and high income (> 3.50)26. Marital status was bifurcated into married and single categories. Participants in marital or cohabitating relationships were designated as "married," whereas those who were separated, widowed, unmarried, or divorced were grouped into the “single” category.

Body mass index (BMI), energy intake, metabolic equivalent (MET), alcohol status, and smoking status were all included in lifestyle-related factors. BMI was employed as a metric for body composition. During the body examination, BMI was computed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Alcohol and smoking status were dichotomously classified as either “yes” or "no."

Health-related factors included the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a reliable tool for evaluating overall physical condition and predicting long-term mortality27. The 24-h dietary recall method was utilized at mobile examination centers to calculate the energy intake by the total nutrient intake on the first day (DR1TOT). Participants also completed a physical activity (PA) questionnaire that adhered to World Health Organization guidelines28. The questionnaire collected data on physical activity type, frequency, and duration over the past seven days. MET values were assigned to evaluate the intensity of PA based on World Health Organization guidelines21,29. The formula for calculating PA (MET-min/week) was: PA (MET-min/week) = MET × weekly frequency × duration of each PA. These values were summed to derive the total PA (MET) value30.

The diagnosis and risk factors for various health conditions were also considered. Hypertension was described as having a history of diagnosed hypertension, using antihypertensive drugs, or having an average systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg. Diabetes was identified by various criteria, including HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random plasma glucose or two-hour plasma glucose (oral glucose tolerance test) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L. Additionally, a history of diagnosed diabetes and the use of antidiabetic medications or insulin were also considered for diagnosis31. Moreover, CVD diagnosis was based on self-reported instances of stroke, heart attack, coronary artery disease, heart failure, or angina32. CKD diagnosis followed the 2012 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines, considering glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria classifications33. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated utilizing the epidemiology collaboration formula to assess CKD. CKD was defined as eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥ 30 mg/g34. Additionally, isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (ID-LC–MS/MS) was utilized to evaluate testosterone and estradiol levels in serum.

Statistical analysis

In this investigation, all analyses integrated sampling weights to ensure the representation of the non-institutionalized civilian population. Cycle weights were recalculated per NHANES guidelines to maintain accuracy. Continuous variables were depicted as geometric means with corresponding interquartile ranges (IQR), whereas categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. α-Klotho levels were transformed with Log-base 2 due to the right-skewed distribution, facilitating an examination of the link between serum α-Klotho levels and the change in the risk of hyperlipidemia resulting from a doubling of these levels. Moreover, α-Klotho levels were stratified into tertiles (T1 to T3). Survey-weighted Wilcoxon tests were employed for continuous variables, while survey-weighted chi-square tests were utilized for categorical variables. Survey-weighted logistic regression analyses were employed to assess the link between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. This investigation involved adjustments for a comprehensive array of covariates. Model 1 adjusted for the lifestyle-related and health-related factors, such as age, sex, race, education level, economic status, marital status, BMI, energy intake, MET, alcohol status, smoking status, CCI, diabetes, hypertension, CVD and CKD. Model 2 further adjusted testosterone and estradiol based on Model 1. Logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between α-Klotho and hyper-LDL, hypo-HDL, hyper-TG or hyper_TC. Moreover, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were utilized to investigate potential non-linear associations between males and females. Subsequently, based on the RCS findings, piecewise logistic regression analysis was executed. This approach facilitated a detailed examination of the link between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia, enabling a thorough comprehension of potential curvilinear associations. Statistical analysis was executed utilizing R (v4.3.1), with significance established at a threshold of P < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The application of exclusion and inclusion criteria meticulously narrowed down the study cohort to 1400 participants, including 337 participants without hyperlipidemia and 1063 participants with hyperlipidemia. Table 1 presents a comprehensive summary the demographic and relevant characteristics of the participants, thoughtfully stratified by sex. It is crucial to acknowledge significant differences between the female and male groups regarding several parameters, such as economic status, marital status, energy intake, MET, alcohol status, smoking status, CKD, testosterone and estradiol. Notably, males exhibited considerably higher energy intake and MET than females. The proportion of males reporting drinking (92.45%) and smoking (53.71%) was significantly higher than that of females, who reported drinking (86.91%) and smoking (41.35%). Conversely, the prevalence of CKD was considerably elevated in females compared to males. Additionally, testosterone and estradiol levels were considerably increased in males compared to females.

The geometric mean of α-Klotho levels, a central aspect of the investigation, was calculated at 779.79 (range 756.56–803.74). No significant difference in α-Klotho levels was noted between the male and female groups (P > 0.05). Furthermore, α-Klotho levels were methodically stratified into three tertiles: T1 (273.10–629.97), T2 (692.97–892.87) and T3 (892.87–5038.30). The distribution of α-Klotho tertiles exhibited no considerable differences between male and female groups (Table 1). The variation in α-Klotho levels within each group was analyzed (Fig. 2). The α-Klotho levels in the hyperlipidemia group were considerably lower relative to those in non-hyperlipidemia group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2A). Specifically, in females, the levels of α-Klotho of the hyperlipidemia group were considerably lower relative to the non-hyperlipidemia group (P < 0.01). No significant difference was observed in the male hyperlipidemia and non-hyperlipidemia groups (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, Table S1 presents the baseline characteristics by tertiles of α-Klotho. BMI and smoke status were significantly different in α-Klotho tertiles.

Association between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia among study participants

Survey-weighted logistic regression analyses were undertaken to scrutinize the link between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia in participants. The findings revealed a considerable reduction in the risk of hyperlipidemia with each doubling of α-Klotho levels (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.47–0.98, P = 0.04) in crude model. However, the other models demonstrated no statistically significant differences (Table 2).

Association of α-Klotho levels with hyperlipidemia in females and males

The participants were stratified by sex and subjected to analysis by logistic regression model. Table 3 illustrates the link between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia within the female participant subgroup. Even after adjusting for all covariates, a significant negative association remained between Log2 α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia. In model 2, each doubling of α-Klotho levels corresponded to a significant reduction in the risk of hyperlipidemia (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.82, P = 0.02). As α-Klotho tertiles increased among females, there was a gradual and significant decrease in the risk of hyperlipidemia. In contrast, logistic regression analysis conducted on males (as detailed in Table 4) demonstrated a positive trend between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia (P > 0.05). In model 2, each doubling of α-Klotho levels corresponded to an increased risk of hyperlipidemia (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.63–2.06, P = 0.63) (Table 4).

The results of logistic regression analyses of the association between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia components were shown in Table 5. The association between α-Klotho and all the components were inverse in both males and females, but only the link between α-Klotho and hyper_TC was statistically significant in females.

The analyses of nonlinear relationship between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia

RCS analysis examined the non-linear correlation between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. The outcomes revealed no non-linear correlation between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipemia in males (Fig. 3B), while a non-linear association was observed in females (Fig. 3A). In females, the inflection point of α-Klotho was determined to be 1106.87 pg/mL. Subsequently, piecewise logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 6). The findings revealed a substantial reduction in the risk of hyperlipidemia for every doubling of α-Klotho levels in model 2 (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.09–0.54, P < 0.01). However, when α-Klotho levels exceeded 1106.87 pg/mL, the association was no longer significant in any models (P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study represents the pioneering sex-based investigation of unveiling a novel relationship between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. Specifically, in females, α-Klotho levels displayed a considerable negative association with hyperlipidemia, characterized by a saturation effect. A consistent positive trend was observed in males between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. Consequently, α-Klotho emerges as a potential predictive biomarker for the risk of hyperlipidemia in the females.

Previous research has highlighted an inverse relationship between serum α-Klotho levels and metabolic syndrome, emphasizing its potential to attenuate risk factors, for CVD, such as TG and TC levels20,21. Additionally, there is a positive association between plasma α-Klotho concentration and HDL levels, and a negative link with TG levels and fibroblast growth factor 23 concentration13,35. The research revealed that the association between α-Klotho and the various components of hyperlipidemia exhibits sex-specific variations, which in turn may account for the observed sex disparities in the association between α-Klotho and the hyperlipidemia risk. The underlying mechanisms driving this association remain unclear and necessitate further exploration.

Prior research has explored the link between hyperlipidemia and Klotho. Investigations on hyperlipidemic rats with non-insulin-dependent diabetes36 and hypercholesterolemic uremic atherosclerotic ApoE knockout mice37, observed a considerable decrease in Klotho expression. The expression of Klotho was reduced by acute inflammation and oxidative stress38,39. In ApoE knockout hyperlipidemic mice, oxidized-LDL (ox-LDL) production is heightened, triggering inflammation, intensifying oxidative stress, and inducing cell apoptosis. Ox-LDL reduces Klotho expression by activating ERK and NF-kB40. Inflammatory cytokines TWEAK and TNF-α downregulate Klotho in renal tubular cells via an NF-kB-dependent mechanism41,42. The investigations suggest that inflammation negatively impacts Klotho expression, whereas Klotho exhibits anti-oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory properties43,44. Klotho improves oxidative stress triggered by ox-LDL by regulating the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway45, and inhibits the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α44. The inhibition of lipid accumulation in the liver and adipose tissue by α-Klotho is achieved by suppressing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. It contributes to improve lipid homeostasis in type 2 diabetes46. These mechanisms elucidate the considerable negative association between Klotho and the risk of hyperlipidemia.

This study also revealed considerable sex-specific variations in the relationship between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. Although the levels of α-Klotho in females were considerably higher in comparison to males, this disparity did not attain statistical significance. Notably, lower α-Klotho levels were observed in females with hyperlipidemia compared to females without this condition. However, there was no significant variation in α-Klotho levels between males with hyperlipidemia and those without this condition. It suggests that there may be a sex-specific variation in the regulatory mechanism between hyperlipidemia and α-Klotho. In this study, no significant association was detected between α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia in males, a phenomenon that remains unexplained by current studies. Prior research indicates that inflammatory responses differ by sex, with females resolving inflammation more rapidly than males47. Additionally, a lower systemic inflammatory burden has been reported in females48. Egr1 and PPARγ have been found to directly upregulate the expression of α-Klotho49,50. Studies suggest that inflammation generally upregulates Egr151, potentially representing a molecular mechanism regulating α-Klotho. Furthermore, PPARγ expression correlates with inflammation induced by hyperlipidemia52. The mechanism may involve the conversion of LDL into oxLDL, which is the endogenous PPARγ ligand, thereby activating PPARγ expression53. Testosterone can increase LDL oxidation54, which suggests a potential pathway for activating PPARγ expression in males. Studies have shown a positive association between testosterone and α-Klotho in males55, in contrast to the absence of such a relationship in females56. Current research suggests that the regulatory mechanisms of α-Klotho expression may vary between males and females, with males potentially being more susceptible to the upregulation of α-Klotho through inflammatory stimulation under hyperlipidemic conditions, which could explain the absence of a significant association between α-Klotho and hyperlipidemia in males. Although the molecular mechanisms are not fully elucidated, sex-based differences in α-Klotho expression have been substantiated by various studies. The influence of Life’s Essential 8 score on serum α-Klotho levels appears to be more pronounced in females57. The negative association between energy-dense diet and α-Klotho levels among sedentary women aged 45–65 years, a relationship not observed in males58. Moreover, serum α-Klotho levels exhibited a negative association with the depression in females, contrasting with a positive association found in males59. In brief, this study offers avenues for future biological explorations into α-Klotho.

This study underscores the pivotal role of α-Klotho in hyperlipidemia risk assessment among community-dwelling females, with profound implications for health management. By quantifying serum α-Klotho levels, healthcare professionals can delineate individuals at elevated risk, facilitating the formulation of tailored health strategies. Women with diminished α-Klotho levels should be encouraged to embrace a preventative lifestyle, characterized by a balanced diet, consistent physical activity, and the eschewing of detrimental habits, to mitigate hyperlipidemia risk. For those identified as high-risk, prioritization of medical resources and services is imperative to ensure prompt medical engagement and intervention. This approach not only enhances individual health outcomes but also optimizes the allocation of healthcare resources, thereby achieving a more judicious distribution of medical assets60.

While this study represents the pioneering effort to unravel the independent protective role of α-Klotho in hyperlipidemia, it is imperative to acknowledge certain limitations. Firstly, the detection of α-Klotho in NHANES is limited to individuals aged 40–79, excluding data on children and young adults. This age constraint emphasizes the need for careful consideration when extrapolating the results to a broader demographic range. Secondly, it’s crucial to recognize that α-Klotho levels can fluctuate due to circadian rhythms and temporal variations, which may introduce measurement variability. Lastly, the observational nature of the study prohibits making causal conclusions about the relationship between α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia. It underscores the importance of further interventional studies to elucidate causality.

The investigation insights into the sex-based relationship between serum α-Klotho levels and the risk of hyperlipidemia. Significantly, the results reveal a considerable negative relationship between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia only in females. Serum α-Klotho levels could be a valuable biomarker for assessing the risk of hyperlipidemia in females.

Data availability

The data of the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalents

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

References

Nelson, R. H. Hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Prim Care. 40, 195–211 (2013).

Iqbal, J., Al Qarni, A., Hawwari, A., Alghanem, A. F. & Ahmed, G. Metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia and regulation of lipoprotein metabolism. Curr, Diabetes Rev. 14, 427–433 (2018).

Kosmas, C. E. et al. The triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) ratio as a risk marker for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Diagnostics 13, 929 (2023).

Bian, A., Neyra, J. A., Zhan, M. & Hu, M. C. Klotho, stem cells, and aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 10, 1233–1243 (2015).

Oishi, H. et al. Klotho overexpression protects against renal aging along with suppression of transforming growth factor-β1 signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 321, F799–F811 (2021).

Akasaka-Manya, K. et al. Decreased ADAM17 expression in the lungs of α-Klotho reduced mouse. J. Biochem. 167, 483–493 (2020).

Kuro-O, M. The Klotho proteins in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 27–44 (2019).

Sahu, A. et al. Regulation of aged skeletal muscle regeneration by circulating extracellular vesicles. Nat. Aging 1, 1148–1161 (2021).

Landry, T. et al. Centrally circulating α-klotho inversely correlates with human obesity and modulates arcuate cell populations in mice. Mol. Metab. 44, 101136 (2021).

Huang, J. W., Fang, W. H. & Chen, W. L. Clinical relevance of serum klotho concentration and sagittal abdominal diameter. J. Clin. Med. 11, 7376 (2022).

Lin, Y. & Sun, Z. Antiaging gene Klotho enhances glucose-induced insulin secretion by up-regulating plasma membrane levels of TRPV2 in MIN6 β-cells. Endocrinology 153, 3029–3039 (2012).

Nakanishi, K. et al. Serum Klotho levels contribute to the prevention of disease progression. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 229–236 (2021).

Semba, R. D. et al. Plasma klotho and cardiovascular disease in adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 1596–1601 (2011).

Żelaźniewicz, A., Nowak-Kornicka, J. & Pawłowski, B. S-Klotho level and physiological markers of cardiometabolic risk in healthy adult men. Aging 14, 708–727 (2022).

Xie, J. et al. Cardioprotection by Klotho through downregulation of TRPC6 channels in the mouse heart. Nat. Commun. 3, 1238 (2012).

Olejnik, A., Radajewska, A., Krzywonos-Zawadzka, A. & Bil-Lula, I. Klotho inhibits IGF1R/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway and protects the heart from oxidative stress during ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci. Rep. 13, 20312 (2023).

Chen, W. Y. Soluble Alpha-Klotho alleviates cardiac fibrosis without altering cardiomyocytes renewal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2186 (2020).

Orces, C. H. The association between metabolic syndrome and the anti-aging humoral factor klotho in middle-aged and older adults. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 16, 102522 (2022).

Jiang, S. et al. The association of serum Klotho concentrations with hyperlipidemia prevalence and lipid levels among US adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 23, 1645 (2023).

Cheng, Y. W., Hung, C. C., Fang, W. H. & Chen, W. L. Association between soluble α-Klotho protein and metabolic syndrome in the adult population. Biomolecules 12, 70 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Association between serum klotho levels and cardiovascular disease risk factors in older adults. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22, 442 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Association between perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl internal exposure and serum α-Klotho levels in middle-old aged participants. Front. Public Health 11, 1136454 (2023).

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106, 3143–3421 (2002).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between blood lead levels and hyperlipidemiais: Results from the NHANES (1999–2018). Front. Public Health 10, 981749 (2022).

Mahemuti, N. et al. Association between systemic immunity-inflammation index and hyperlipidemia: A population-based study from the NHANES (2015–2020). Nutrients 15, 1177 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of association between visceral adiposity index and serum anti-aging protein Klotho in adults. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1082504 (2023).

Charlson, M. E., Carrozzino, D., Guidi, J. & Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 91, 8–35 (2022).

Hallal, P. C. et al. Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 380, 247–257 (2012).

Organization. WH: Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. https://www.whoint/ncds/surveillance/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guidepdf

Chen, L. et al. Risk/benefit tradeoff of habitual physical activity and air pollution on chronic pulmonary obstructive disease: Findings from a large prospective cohort study. BMC 20, 70 (2022).

Cosentino, F. et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 41, 255–323 (2020).

Ainiwaer, A. et al. Association of red cell distribution width (RDW) and the RDW to platelet count ratio with cardiovascular disease among US adults: A cross-sectional study based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2020. BMJ Open 13, e068148 (2023).

Inker, L. A. et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 63, 713–735 (2014).

Jespersen, T. et al. Light wine consumption is associated with a lower odd for cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 28, 1133–1139 (2018).

Yamazaki, Y. et al. Establishment of sandwich ELISA for soluble alpha-Klotho measurement: Age-dependent change of soluble alpha-Klotho levels in healthy subjects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 398, 513–518 (2010).

Nagai, R. et al. Endothelial dysfunction in the klotho mouse and downregulation of klotho gene expression in various animal models of vascular and metabolic diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 57, 738–746 (2000).

Yu, J., Deng, M., Zhao, J. & Huang, L. Decreased expression of klotho gene in uremic atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 261–266 (2010).

Lim, K. et al. Vascular Klotho deficiency potentiates the development of human artery calcification and mediates resistance to fibroblast growth factor 23. Circulation 125, 2243–2255 (2012).

Thurston, R. D. et al. Tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma down-regulate Klotho in mice with colitis. Gastroenterology 138(1384–94), 1394.e1–2 (2010).

Sastre, C. et al. Hyperlipidemia-associated renal damage decreases Klotho expression in kidneys from ApoE knockout mice. PLoS ONE 8, e83713 (2013).

Martín-Núñez, E. et al. Klotho expression in peripheral blood circulating cells is associated with vascular and systemic inflammation in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Sci. Rep. 12, 8422 (2022).

Moreno, J. A. et al. The inflammatory cytokines TWEAK and TNFα reduce renal klotho expression through NFκB. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1315–1325 (2011).

Cui, W., Leng, B. & Wang, G. Klotho protein inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative injury in endothelial cells via regulation of PI3K/AKT/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 97, 370–376 (2019).

Wang, N., Ma, J., Ren, Y., Xiang, S. & Jia, R. Secreted klotho from exosomes alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 11(6), 3375–3383 (2019). Erratum in: Am J Transl Res.11, 6701 (2019).

Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, C. Klotho ameliorates oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL)-induced oxidative stress via regulating LOX-1 and PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathways. Lipids Health Dis. 16, 77 (2017).

Gu, H. et al. Soluble Klotho improves hepatic glucose and lipid homeostasis in type 2 diabetes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 18, 811–823 (2020).

Shabbir, A., Rathod, K. S., Khambata, R. S. & Ahluwalia, A. Sex differences in the inflammatory response: Pharmacological opportunities for therapeutics for coronary artery disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 61, 333–359 (2021).

Malek, A. M., Alper, S. L. & Izumo, S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA 282, 2035–42 (1999).

Chen, C. D., Rudy, M. A., Zeldich, E. & Abraham, C. R. A method to specifically activate the Klotho promoter by using zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks and from naturally engineered Egr1 transcription factor backbone. FASEB J. 34, 7234–7246 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Klotho is a target gene of PPAR-gamma. Kidney Int. 74, 732–739 (2008).

Trizzino, M. et al. EGR1 is a gatekeeper of inflammatory enhancers in human macrophages. Sci. Adv. 7, eaaz8836 (2021).

Lee, S. H. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveal cellular diversity of aortic valve and the immunomodulation by PPARγ during hyperlipidemia. Nat. Commun. 13, 5461 (2022).

Itoh, T. et al. Structural basis for the activation of PPARgamma by oxidized fatty acids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 924–931 (2008).

Zhu, X. D., Bonet, B. & Knopp, R. H. 17beta-Estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone inversely modulate low-density lipoprotein oxidation and cytotoxicity in cultured placental trophoblast and macrophages. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 177, 196–209 (1997).

Glover, F. et al. The relationship between klotho, testosterone, and sexual health parameters among US adult men. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 47, 523–533 (2024).

Cao, Q. et al. The association between testosterone and serum soluble klotho in the females: evidence from the NHANES database. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1335611 (2024).

Kadier, K. et al. Maintaining ideal cardiovascular health is associated with higher serum anti-aging protein klotho in the middle-aged and older populations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 28, 100224 (2024).

De-la-O, A. et al. Association of energy and macronutrients intake with S-Klotho plasma levels in middle-aged sedentary adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 26, 360–366 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sex differences in the association between serum α-Klotho and depression in middle-aged and elderly individuals: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2007–2016. J. Aff. Disord. 337, 186–194 (2023).

Liu, P. et al. Lowering the risk of hyperuricemia and gout is associated with ideal cardiovascular health. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43, 167 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Zhiyun for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by Hebei Province Medical Science Research Project Program (Grant No. 20211391) and the Funding for Excellent Talent Project in Clinical Medicine of Hebei Province Government (Grant No. ZF2023205).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu Han and Yile Zhao designed the study. Xijuan Jiang, Yabin Qin, Yinghua Ma and Zhihua An analyzed the data. Yu Han, Chao Liu, Ying Nie and Na An wrote the manuscript. Yu Han and Yile Zhao critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to submit the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NHANES procedures were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board, and the informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the surveys.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Liu, C., Nie, Y. et al. Sex differences in the association between serum α-Klotho levels and hyperlipidemia: a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2013–2016. Sci Rep 15, 4919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85018-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85018-3