Abstract

Recent advances highlight the limitations of classification strategies in machine learning that rely on a single data source for understanding, diagnosing and predicting psychiatric syndromes. Moreover, approaches based solely on clinician labels often fail to capture the complexity and variability of these conditions. Recent research underlines the importance of considering multiple dimensions that span across different psychiatric syndromes. These developments have led to more comprehensive approaches to studying psychiatric conditions that incorporate diverse data sources such as imaging, genetics, and symptom reports. Multi-view unsupervised learning frameworks, particularly deep learning models, present promising solutions for integrating and analysing complex datasets. Such models contain generative capabilities which facilitate the exploration of relationships between different data views. In this study, we propose a robust framework for interpreting these models that combines digital avatars with stability selection to assess these relationships. We apply this framework to the Healthy Brain Network cohort which includes clinical behavioural scores and brain imaging features, uncovering a consistent set of brain-behaviour interactions. These associations link cortical measurements obtained from structural MRI with clinical reports evaluating psychiatric symptoms. Our framework effectively identifies relevant and stable associations, even with incomplete datasets, while isolating variability of interest from confounding factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

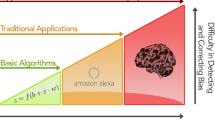

Contemporary psychiatry is undergoing a transition from a symptom-based approach towards one based upon an understanding of their underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Achieving this goal is an ongoing process that demands a combination of scientific and technological advances as well as a shift towards a more patient-centric approach1. Identifying relationships between behaviours and brain measurements is a key aspect of this paradigm. However, behaviours are complex and often result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors. Additionally, the possible presence of comorbidities implies that multiple behaviours consistent with different mental disorders may occur simultaneously. Also, a given disorder may have multiple manifestations across individuals. This complexity challenges the idea that a single behavioural signature can be associated with a given disorder. In the early 2010s, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) assessed the results of diagnostic studies in psycho-pathologies, particularly in light of the increasingly abundant available data in neuroimaging, genomics and psychology. The results did not appear to align with the categories of traditional psychiatric research (brain anatomy, refined descriptions of the symptoms, or operational criteria like DSM2), but instead tended to be related to functional domains (e.g. fear, working memory)3. These conclusions were published as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) which provided recommendations for properly addressing the aforementioned complexity4. In the RDoC framework, it is possible to formulate new hypotheses, such as classifying as “abnormal” functions certain behaviours that were classically referred to as complaints, symptoms or syndromes. The RDoC promotes dimensional and transdiagnostic approaches. To that end, it incorporates different types of data like genetic, biological, environmental, and lifestyle factors in the research on personalised psychiatry. In recent years, the transdiagnostic literature in psychopathology has developed along these lines by considering that many functions can be placed on a continuum ranging from normal to abnormal5. It should be noted that these dimensional and transdiagnostic approaches remain challenging due to the categorical nature of clinical scales. These multi-view datasets require the development of new methods for data integration. Some recently developed transdiagnostic approaches investigate a general psychopathological factor, known as the p-factor6,7. This p-factor subtends a common mechanism for several higher-order psychiatric dimensions (which could correspond to the latent representations/variables below), that in turn would influence the commonly observed psychiatric syndromes. The aim of these studies is to look for neural correlates of the p-factor using different biological markers, such as imaging or genetics.

At the same time, new methods are being developed to integrate multi-view data, including structural or functional characteristics of the brain, tabular data from electronic case report forms, genotyping, and lifestyle conditions. Such developments are being driven by the emergence of large multi-centre cohorts of at-risk individuals or patients, compatible with the RDoC framework. Publicly available cohorts include diverse psychological scores as well as imaging phenotypes such as regional cortical thickness and gyrification. The simplest integrative methods involve concatenating views of different types to train a predictor. The selected variables can then be examined for interpretability. Modern integrative approaches attempt to model the correlation structure between views to derive latent representations8,9,10. Interpretation can then be carried out by studying the associations between these latents and target variables. In this paper, we will focus on the latter approach, namely an integrative association study. First, we describe a state-of-the-art generative deep learning approach that can handle missing data, that scales to multiple modalities, and which has interesting disentanglement capabilities. The aim is to jointly model an embedding latent space of MRI and clinical scores to capture intra- and inter-view structures. Secondly, instead of exploring this latent space, we propose to use a Digital Avatar Analysis (DAA) method to interpret the joint relationships learned by the multivariate generative model, producing results in terms of brain-behaviour associations. By introducing a subject-level perturbation in the clinical view and passing it through the generative model, an avatar can be simulated by observing the perturbation effects on the complementary view (i.e., MRI cortical data). Using the virtual data generated, an association study based on linear regressions is carried out to find relationships between the views considered. Finally, attention is paid to improving the stability of the observed inter-view associations across the different sources of variability. These three main points are further developed in the following paragraphs on representation learning, interpretability and stability:

-

Representation learning: The RDoC framework requires the consideration of multi-view data. Multi-view representation learning can be addressed in many ways11. Some recent approaches propose to handle multi-view integration with deep learning models using fusion mechanisms at different levels in the network, using various operators such as attention mechanisms12 or channel-exchanging strategies13. Such integration methods have been applied in psychiatry, for instance to discover biomarkers related to schizophrenia14. However, such types of model are designed for, and are usually applied to single-task. We believe that an unsupervised or self-supervised approach might be more suited for capturing the complex variability of psychopathologies. Of particular interest, Probabilistic Graph Models (PGM) are designed to describe the latent generative process of the data. Their probabilistic formulation offers a natural way to cope with missing modalities, and their generative aspect provides a form of interpretatability. State-of-the-art implementations of multi-view PGMs include multi-view Variational Auto-Encoders (mVAE) which are extensions of the traditional VAE15. We propose to take advantage of the mVAE’s ability to capture the joint distribution of data from different views and to disentangle confounding factors in the learned latent space16,17. When using such models, a prior distribution has to be chosen for the distribution of the latent variables. It plays a crucial role in constraining the learning process and influences the structure of the learned latent space. A classical choice for this prior distribution is the standard Gaussian distribution8,18,19,20. Recently proposed alternatives include Product of Experts (PoE), Mixture of Experts (MoE), or a combination of the two (MoPoE)8,9,10. The rationale for using an mVAE lies in its ability to capture shared latent representations, taking into account not only the intra-view correlation structure but also the inter-view correlation. However, questions remain about some of their limitations in modelling only a shared latent space where information from different views is integrated21. Recent research advocates exploring alternatives involving view-specific latent spaces10,17,22,23. In this work, we propose to use a MoPoE-VAE as a specific mVAE. The MoPoE-VAE can learn view-specific and shared representations during the training phase, and is expected to reduce the influence of non-interest factors (such as the imaging acquisition site effect) in the shared latent space. The MoPoE-VAE was compared to the PoE-VAE and MoE-VAE models on three synthetic datasets where the input source of variabilities are controlled10: PolyMNIST with five simplified modalities, the trimodal matching digits dataset MNIST-SVHN-Text, and the bimodal Celeba dataset with images and text. Overall, the MoPoE-VAE was shown to achieve the best results in terms of overall coherence.

-

Interpretability: Using an mVAE for integrative association analysis has the advantage of capturing complex relationships across multiple views. However, this is at the expense of interpretability. Enforcing interpretation capabilities for deep learning models, and more specifically for mVAEs, remains an open question. In previous work, we developed an interpretability method to explain the information learned by an mVAE by exhibiting the associations between brain pattern and behavioural scores24. The generation of data through individually controlled modifications using the mVAE generative process is at the core of our method. We have coined the term Digital Avatars (DA) to express this concept. Harnessing the generative capabilities of a trained mVAE, we generate sets of DAs from left-out subjects. A DA of a particular individual is obtained by realistically varying one of its behavioural scores and reconstructing the corresponding brain image using the model. The analysis performed on the obtained sets of DAs yields what we hereafter call a Digital Avatars Analysis (DAA). This allows for the exploration of brain-behaviour relationships through linear model fitting for all pairs of behavioural scores and image measurements. The interpretability of DAs is enhanced by their exclusive reliance on the joint latent representation. However, DAA results are strongly affected by the epistemic variability inherent to training stochasticity and weight initialisation25. We mitigate this effect through ensembling using multiple trained mVAE models with different initialisation parameters on the same training subjects26,27. This strategy, which acts as a regularisation of the DAA, is parameterised by the number of trained models for ensembling and is hereafter referred to as regularised DAA (r-DAA). In summary, we expect that an ensemble of DAAs will provide a more comprehensive understanding of brain-behaviour associations than a single DAA.

-

Stability: The stability of results in integrative association studies within a multi-view dataset is a natural objective and a necessary condition for achieving reproducibility. Traditional approaches use cross-validation strategies that often include the definition of a downstream auxiliary task for model selection. However, it has been shown that these procedures may not consistently identify stable associations28,29,30,31. This is particularly true when correlations between views are low or sample sizes are small32,33,34,35,36. The stability challenge remains an open question, especially in the context of the DAA method described above. We advocate the adoption of a robust stability selection framework to address this concern. Stability selection is a promising machine learning technique that efficiently exploits the regularisation mechanisms embedded in the optimisation problems37. For example, in a classification task this method has been shown to consistently identify the structures on which the classifier is built. This is an advantage in terms of robustness. In this study, we extend Meinshausen’s concepts on the stability of selected features to the stability of selected associations. We find that the brain-behaviour associations generated with DAA are not only affected by the epistemic variability described above, but are also sensitive to aleatoric variability (i.e. the variability observed in the data that cannot be explained by the model). To reduce this variability, the stability selection procedure splits the dataset multiple times to generate different training and left-out splits. This allows us to generate stability paths which identify stable brain-behaviour associations. This in turn contributes to a more reliable exploration of brain-behaviour relationships in the context of multi-view data analysis.

Overall, we present an empirical framework for extracting a consistent set of brain-behaviour associations from a multi-view dataset containing clinical behavioural scores and brain imaging features. This framework is based on the stable selection of r-DAA output associations. Our methodological contributions are threefold. First, we propose a r-DAA that uses a weighted ensembling procedure to consolidate interpretations. Second, we introduce a stability selection procedure to generate a set of robust brain-behaviour associations. Finally, we confirm that our mVAE-based procedure alleviates the need for additional normalisation. The proposed framework is applied to a publicly available cohort of at-risk children with notable behavioural symptoms. Our results reveal transdiagnostic brain-behaviour associations common to several psychiatric syndromes, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Methods

This section introduces the concept of discovering stable associations in multi-view data using association study and stability selection. The digital avatar-based association study, referred to as DAA, is designed to find associations from a trained mVAE in heterogeneous multi-view datasets with potential missing data. Then, a regularised DAA (r-DAA) procedure is employed to mitigate the epistemic uncertainty inherent when training neural networks. Regularisation is achieved by ensembling the results of several DAAs in order to retain meaningful associations. Finally, stability selection is applied to r-DAA by resampling the original dataset. This strategy is intended to curb the aleatoric uncertainty present in the observed data. Associations consistently selected by the r-DAA across the resampling splits are considered stable. The proposed approach consists of three nested steps listed from the innermost to the outermost: (1) DAA - training an mVAE and conducting an association study, (2) r-DAA - ensembling results from several DAAs derived using a single left-out set but trained with different initialisations and batches, and (3) stability selection - performing several r-DAAs on different left-out sets to select stable associations. These steps are described below and illustrated in Fig. 1, Fig. Supplemental S4 and detailed in Alg. Supplemental S5.1.

Interpretation framework based on the DAA. The three parts of the process are represented by the three columns. The DAA column shows candidate associations (links between brain and behaviour) generated by the DAAs. A hierarchical bootstraping procedure organises the following parts. The r-DAA column shows the ensembling step performed on associations derived from model communities (community size ranging from 1 to \(n_E\)) trained with the same training data but with different initialisations. Finally, the stability selection column shows the construction of stability paths parameterised by \(n_E\). From the generated N binary decision support, a stability selection procedure is used to retain associations with stability path \(\Pi \ge \pi _\text {thr}\).

Multi-view dataset

This study uses the Healthy Brain Network (HBN) cohort38. This dataset is a multi-centre, transdisciplinary clinical study. It includes a variety of assessments, including imaging, and a comprehensive set of psychological and clinical evaluations for a better understanding of psychiatric disorders. Inclusion criteria are not diagnosis-dependent, but rather encompass an at-risk population with notable behavioural symptoms. Specifically, subjects were selected based on the presence of behavioural traits related to ADHD or ASD. As such, the dataset allows for the study of varying manifestations of psychiatric syndromes and provides an opportunity to explore methods for new biomarker discovery and dimensional analysis.

In a previous study, our group identified seven behavioural assessments that capture the most salient dimensions in ASD patients39. These seven assessments are: the quantitative measure of clinical autistic traits as defined by the parent Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), the hyperactivity levels as determined by the hyperactivity subscale within the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-ha), the anxiety scale measured using the total score from the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders Parent-Report (SCARED), the irritability scale defined using the total score of the Affective Reactivity Index Parent-Report (ARI), and finally, the levels of depression, aggression, and attention problems as determined by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL-wd, CBCL-ab, and CBCL-ap, respectively). In total, 2454 subjects were retained.

The MRIs were acquired at four sites: a mobile 1.5T Siemens Avanto on Staten Island, a 3T Siemens Tim Trio at the Rutgers University Brain Imaging Center, and 3T Siemens Prisma at the CitiGroup Cornell Brain Imaging Center and at the CUNY Advanced Science Research Center. Collected T1-weighted images were preprocessed using FreeSurfer40. All results were manually reviewed in house. The Euler number was chosen as a quality metric summarising the topological complexity of the reconstructed cortical surfaces41. Specifically, an exclusion threshold for Euler numbers under \(-217\) was applied to yield 2042 selected subjects. Finally, cortical measurements based on three metrics - cortical thickness, curvature, and area - were averaged in the 148 cortical Regions Of Interest (ROIs) defined by Destrieux’s parcellation42.

The proposed brain-behaviour integrative analysis considers these two views. First, the electronic Case Report Forms (eCRF) view consists of the \(p_{eCRF} = 7\) behavioural scores. Second, the ROI view is composed of the \(p_{ROI} = 444\) cortical features from the three considered metrics across the 148 ROIs. In total, our dataset comprises 2991 subjects amongst whom 1505 have both complete views (referred to as complete dataset in Fig. Supplemental S4(a)), and 1486 have only one of the two views available (referred to as incomplete dataset in Fig. Supplemental S4(a)). Missing views remain a common problem in data integration and are caused by factors not known in advance. Most traditional data mining and machine learning approaches operate on complete data and fail when data is missing. As fallback strategies, some models rely only on samples with all views available, or on an auxiliary inference step that generates missing views. Our goal here is to use a model that can accommodate for missing views allowing us to maximise the dataset size without introducing an algorithmic bias.

The data acquisition protocol was approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board, it is conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki for human research and is described elsewhere38. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s)38.

Digital avatar analysis

The multi-view deep learning modeling we use has generative capabilities and the exploration of a disorder spectrum can be achieved through the generation of so-called Digital Avatars (DAs), i.e. digital representatives obtained in virtual but plausible clinical scenarios. In this work we employ an mVAE, and more specifically a MoPoE-VAE (see Supplemental S1 for the specifications and training). In brief, the proposed architecture consists of two encoders and decoders in the form of multilayer perceptrons which result in view-specific latent spaces of dimension 1 and 20 for the eCRF and ROI views respectively, as well as a shared latent space of dimension 3. The training set comprises all subjects with incomplete data and those with complete data that were not retained as the left-out subjects. In our setting, we use \(L=301\) subjects as the left-out set. After training, the MoPoE-VAE does not directly yield brain-behaviour associations. The insights gained from the model can be leveraged to unveil relevant pairwise associations between views. Starting from the left-out subjects (i.e. those unseen during training), we modify each subject’s clinical score and generate a set of \(T=200\) DAs with the model. Thus, each generated DA bears brain imaging features at a given clinical state. From this set of virtual neuroimaging data, a conventional association study is performed to find brain-behaviour relationships. For each score of the eCRF view, we perform \(p_{ROI}\) univariate association studies. In a previous publication, we introduced this DA analysis24 and we describe hereafter in detail how the DAs are obtained and analysed.

For the DAA step, we use the left-out set. Note that in our case all left-out subjects should have complete data. In what follows, we consider without loss of generality the case where the eCRF view has only one score. Our aim is to create a set of DAs from each of the L left-out subjects. Let \(s=(s^1, \dots , s^L) \in \mathbb {R}^L\) be the eCRF scores for all subjects, and \(m=[m^1, \dots , m^L] \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times p_{ROI}}\) their ROI cortical measurements. Note that this specific case can be generalised to all clinical scores and additional views. The general idea is to modify s into \({\hat{s}}\), use a trained model to generate cortical measurements and observe how these modifications affect the generated cortical measurements \({\hat{m}}\), thus yielding a virtual pair (\({\hat{s}}\), \({\hat{m}}\)). An initial, simplistic approach to perturbing s is to sample linearly or randomly between the selected score percentiles, or even to bootstrap values across subjects. Instead, our approach relies on a more realistic simulation by using the latent embeddings of a trained model to build a realistic law of perturbation. We hypothesise that such an approach, which models the composite variability of subjects measurements, facilitates the discovery of interesting brain-behaviour relationships. Indeed, the variability in the simulated avatars integrates both subject-specific and population-level variability. The latter is captured through the learned variance that is shared across the population. Our goal is to comprehensively assess what the model has learned by introducing subject-level perturbations and investigating their effects on the reconstructed DAs. The proposed strategy can be divided into three stages - inference, simulation, and association -, which are outlined below and illustrated in Fig. Supplemental S4(c) and Fig. Supplemental S3.

Inference - estimating likelihood distributions

For a given subject \(i \in \{1, \dotsc , L\}\), we propose to use \(p_\theta (s^i|z^i)\), the likelihood distribution of observations conditioned on the latent variable learned from the data, to sample DA score values. We now have to estimate this likelihood distribution \(p_\theta (s^i|z^i)\) , where \(\theta\) denotes the weights of the eCRF view decoder and \(z^i = (z_{\text {eCRF}}^i, z_{\text {Joint}}^i)\) is the latent representation of \(s^i\), consisting of the eCRF specific and joint latent representations, respectively (see Supplemental S1). Provided that our model is properly trained, such clinical score distributions will optimally reflect the training data. The estimation of \(p_\theta (s^i|z^i)\) is obtained by drawing \(D=1000\) realisations of \(z^i \sim q_\phi (z^i|s^i,m^i)\), where \(\phi\) are the weights of the MoPoE-VAE encoders (see Supplemental S1). Passing these latent representations to the eCRF decoder provides a good estimate of \(p_\theta (s^i|z^i)\) after averaging the D decoded reconstructions15. Note that the same strategy can be applied to categorical data by approximating the parameters of a Bernoulli distribution instead of a Gaussian.

Simulation - sampling realistic values

Given a subject \(i \in \{1, \dotsc , L\}\), T samples are drawn from \(p_\theta (s^i|z^i)\) resulting in T perturbations \({\hat{s}}^i \in \mathbb {R}^T\). Repeating this sampling for all subjects i, the generated set forms our DAs with perturbed eCRF observations \({\hat{s}}=[{\hat{s}}^1, \dots , {\hat{s}}^L] \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times T}\). Importantly, when we generalise to multiple clinical scores only one score is perturbed at a time. Finally, the perturbed ROI measurements are generated using a forward pass by considering \({\hat{s}}\) and the corresponding ROI features m as model inputs. This results in a set of T perturbed ROI measures representing our DAs \({\hat{m}} \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times T \times p_{ROI}}\). As a compromise between computational cost and accuracy, we set \(T=200\).

Association - computing inter-view associations

We search for associations between a clinical score and each ROI measurement. We refer to the generated DA score values as \({\hat{s}} \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times T}\), and generated DA ROI measurements as \({\hat{m}} \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times T \times p_{ROI}}\). Associations are obtained using hierarchical regression models43. Specifically, for each image feature \(k \in \{1, \dots , p_{ROI}\}\) a linear regression of the form \({\hat{s}}^i = c^i_k + b^i_k {\hat{m}}^i_k + \epsilon ^i_k\) is fitted for each subject i. The resulting slopes are averaged over all subjects as \(\beta _k = \frac{1}{L}\sum _{i=1}^L b^i_k\). Performing the same analysis for all available eCRF scores results in the association vector \(\beta \in \mathbb {R}^{p}\), where \(p = p_{ROI} \times p_{eCRF}.\) This vector encompasses all potential associations between the \(p_{eCRF}\) clinical scores of the eCRF view and the \(p_{ROI}\) cortical features of the ROI view.

Regularised digital avatar analysis

In our former work24 we observed that the associations were not stable, even when the model was retrained on the same training set and evaluated on the same left-out set. This instability is likely due to epistemic variability25,44 and has mainly been studied in the supervised setting45,46. In feature selection using deep learning, studies have shown that ensembling can enhance stability and thus mitigate epistemic variability26. We propose to repeat the previous DAA step \(n_E\) times. Note that the training and left-out sets remain the same throughout these \(n_E\) iterations, and only the random weights initialisations and training batches vary (see Fig. Supplemental S4 blue dashed box). By ensembling, our objective is to identify stable associations from the association matrix \(\varvec{\beta } = [\beta ^1, \dots , \beta ^{n_{E}}] \in \mathbb {R}^{n_E \times p}\) derived from the \(n_E\) DAAs. Like classical deep ensembling, our approach involves combining candidate associations (i.e., model predictions in supervised settings46) suggested by the \(n_{E}\) DAAs and aggregated in matrix \(\varvec{\beta }\). The procedure requires an aggregation function f and a decision function g. The former summarises the \(n_{E}\) associations coefficients and the latter generates a binary decision support from the aggregated coefficients, which is designed to retain meaningful associations. Formally, let \(f: \mathbb {R}^{n_{E} \times p} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{p}\) be an aggregation function and \(g: \mathbb {R}^{p} \rightarrow \{0,1\}^{p}\) decision function. The composition \(g\circ f\) forms the proposed ensembling, which is outlined below and illustrated in Fig. Supplemental S4(d) (see Alg. Supplemental S5.1(b) and Supplemental S5.2(b) for further details).

Aggregation - f

The role of the aggregation function f is to assign an importance to each association from the aggregated association matrix \(\varvec{\beta }\). We initially opted for the arithmetic mean, although alternative functions such as the sample median or maximum could also be used. However, the quality of the estimated \(n_{E}\) models is not accounted for by any of these functions. In fact, some models may converge to local minima of the optimised loss function resulting in worse models and representations. Such behaviour can produce outlier associations26. Owing to this, we subsequently opted for a weighted average whose weights reflect the quality of the estimated models. The weights are determined by the joint latent space’s ability to capture a significant proportion of the eCRF-related variability. We use the Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA)47 to compute correlations between the joint latent space and the eCRF scores (see Supplemental S2 and Alg. Supplemental S5.2 for details).

Decision - g

The purpose of the decision function g is to obtain a binary decision support from the aggregated coefficients. We selected the top \(n_\text {select}=12\) associations with the greatest amplitudes for each score-metric pair (i.e. we select \(\# \text {associations} = n_\text {select} \times p_{eCRF} \times 3 \text { metrics}\)). This allowed us to choose a subset of the most informative associations for each score-metric pair, enhancing interpretability. Instead of simply specifying a numeric threshold or obtaining one with some built-in heuristic, we preferred setting the number of features explicitly. This approach provides consistency across score-metric pairs and DAAs.

Stability selection

Stability selection, defined for penalised machine learning37, is designed to reinforce feature selection through the definition of stability paths. Stability paths are defined for one feature and parameterised by regularising parameter; they are meant to represent the probability of selecting that feature when training the same algorithm with some regularisation parameter on different random splits. We extend this methodology to our brain-behaviour association study. In our context, the regularisation parameter is the number of models \(n_E\) considered in the ensembling step. We repeat the r-DAA (see Section 2.3) N times, using different splits of the original dataset, and setting the regularisation parameter \(n_{E} \in \{1, \dots , 20\}\). This approach allows us to model the aleatoric uncertainty inherent to the considered population25. It involves three steps outlined below, illustrated in Fig. Supplemental S4(e) and detailed in Alg. Supplemental S5.1(c) and Supplemental S5.2. First, we define a valid splitting strategy. Then, we repeat the r-DAA N times by varying the regularisation parameters \(n_{E}\), enabling us to estimate stability paths. Finally, we define a criterion for assessing the stability of the results obtained across the N splits.

Splitting strategy

Our dataset consists of two parts: 1505 subjects with complete data and 1486 subjects with incomplete data (see Section 2.1). It is important to note that subjects with missing views can only be used in the model training step. For each split, 2690 out of the 2991 available subjects are used in the training set. This number includes the 1486 subjects with incomplete data and 1204 randomly selected subjects with complete data. The remaining \(L=301\) subjects with complete data form the left-out set (see Fig. Supplemental S4). To maintain population statistics (including age, sex, and acquisition site distributions) we employ shuffled iterative stratification48. Although using the entire incomplete dataset at each training iteration may appear as a limitation, it is effectively mitigated by the use of different shuffled batches at each training epoch. We opt for \(N=100\) splits.

Stability paths

Each r-DAA with regularisation parameter \(n_{E}\) produces a decision support \(S^j(n_{E}) \in \{0,1\}^{p}\) for a given split \(j \in \{1, \dots , N\}\). The stability paths \(\Pi ^{n_{E}} \in [0,1]^{p}\) are the probability that each association be selected across the N splits. It is obtained by averaging all the calculated binary decision supports as:

Stability criterion

The stability criterion analyses the stability paths and defines which associations are considered stable. If the probability of an association happens to be greater than a user-defined threshold \(\pi _\text {thr}\) \(\in [0,1]\) for a specific regularisation parameter \(n_{E}\), then the corresponding association is selected. Finally, we define the set of stable features as:

In words, this means that associations with a high probability of selection for any regularisation parameter are retained as stable associations, while those with a low probability are dropped.

Results

Models inspection

To evaluate the information encoded in the various latent spaces of the trained models, we employ RSA47 (see Supplemental S2 for details). The RSA results in Table 1 depict the relationships between the eCRF, Joint, and ROI latent spaces and each eCRF score, along with age, sex, and image acquisition site covariates. In short, we computed the Kendall \(\tau\) correlations for every \(N=100\) splits and corresponding \(n_E=20\) models. The reported \({\bar{\tau }}\) values are averaged across these \(N \times n_E\) experimental settings (see Supplemental S2).

Notably, each eCRF score strongly correlates with the eCRF-specific latent space, as highlighted in pink in Table 1. This is noteworthy as the models successfully learned a significant amount of variability associated with the eCRF view in a single one-dimensional space. This result is somewhat unsurprising, as the scores are correlated (see Supplemental S2). Additionally, it suggests that this latent space does not inform about age, sex, or image acquisition site. In contrast, the latent space specific to the ROI view does not correlate significantly with the eCRF scores, with the only exception being the ARI score. Note that it correlates significantly with age, sex, and image acquisition site, as highlighted in orange in Table 1. Finally, we highlight in salmon in Table 1 what the joint latent space has learned. These representations exhibit moderate to high correlations with each score. Furthermore, they show no correlation with acquisition site or sex and weak correlation with age. This implies that the brain-behaviour relationships, as depicted in the MoPoE-VAE joint latent space, are influenced by age-related information.

Stability selection from r-DAA

By increasing the number of models and applying a stability selection procedure, we aim to increase the stability of the sets of brain-behaviour associations supported by our multi-view dataset. Below, we consider the associations of the SRS scores with the cortical thickness measurements. Figure 2 illustrates the computed association trajectories taken by the considered 148 ROIs. This illustration is inspired by the figure of merit proposed in the seminal paper of Meinshausen et al.37. In Fig. 2a we plot the trajectories of aggregated \(\beta\) values (i.e. effect sizes) using a mean function for f, against the number of models \(n_E\) (the regularising parameter). Some trajectories become more prominent than others as the number of models increases. However, they are almost indistinguishable from other trajectories, which remain densely packed with low values. This suggests that we can isolate some (but perhaps not all) stable associations by increasing the number of models aggregated in the r-DAA. Note that the plot in Figure 2a was produced with one of the \(N=100\) stability selection splits.

Figure 2b presents the stability paths \(\Pi\) for each ROI with respect to the number of models \(n_E\). This probability is computed per Eq. 1 and summarises, for each path, the \(N=100\) stability selection splits. Here, the aggregation function f is the arithmetic mean. These results suggest that the most stable ROIs, characterised by higher probabilities \(\Pi\), are easily identifiable. The stable paths reach a plateau when the number of models (i.e. the regularisation hyperparameter) ranges between 5 and 10 models, depending on the considered ROI.

Figure 2c is similar to Fig. 2b, but the procedure uses the RSA-weighted average as the aggregation function f instead of the (unweighted) arithmetic mean (see Alg. Supplemental S5.2). The results suggest that stability is only slightly affected by the choice of the aggregation function f. We keep the RSA-weighted average because it may be more robust to outlier models. We apply a threshold of \(\pi _\text {thr}=0.4\) (as illustrated by the dashed red line) to retain stable associations. For comparison, the ROIs obtained are coloured identically in the different plots. Comparing Fig. 2b or Fig. 2c with Fig. 2a reveals that a high \(\beta\) coefficient amplitude is not always a good indicator of stability. In fact, the ROIs represented by pink or light purple paths in Fig. 2a are indistinguishable from other black dotted lines (i.e. unselected ROIs). However, these ROIs convey some of the most stable associations (\(\Pi \simeq 0.7\) when \(n_{E} = 20\)).

Table 1 shows that for our dataset, our models do not best capture the variability of the SRS score. To observe the influence of the selected score and metric on the stability paths, we examine another configuration. The association between the SDQ-ha score and the area metric shows similar trends (see Supplemental S6).

Investigation of the ROIs association with SRS in thickness. Each line corresponds to an ROI. Dotted black lines are not selected by the stability selection procedure (using the threshold \(\pi _\text {thr} = 0.4\) represented by the red horizontal dotted line in (c)) when using the RSA-weighted mean as an aggregation function. The selected ROIs are coloured consistently across the three plots. The three plots display (a) the mean coefficients aggregated across models for a given split, (b) the ROIs stability paths \(\Pi\) when using a mean operator to aggregate the DAA coefficients, and (c) the ROIs stability paths \(\Pi\) when using a RSA-weighted mean operator to aggregate the DAA coefficients against the number of models in the ensembling \(n_E\).

Transdiagnostic-association spatial support

Transdiagnostic assessment: display ROIs associated with the selected SRS, SDQ-ha, SCARED and CBCL-wd eCRF scores for each of the cortical thickness, curvature and area metrics. In (a), the highlighted ROIs are displayed on an inflated surface. Note that the same colour code is used in all plots. In (b), (c), and (d), the polar plots indicate the sign of each association (negative if the bar is pointing inside the circle, and positive if it is pointing outwards), for the thickness, curvature, and area metrics, respectively. Note that only the retained associations are displayed. The following notations are used: L: left, R: right, Ci: cingulate, Oc: occipital, Te: temporal, S: sulcus, G: gyrus, Mid: middle, Post: posterior, Dors: dorsal, Med: medial, Marg: marginal, Ant: anterior, PeriCal: pericallosal, Sup: superior, Li: lingual, Pl: plan, Pola: polar.

The interpretation brought by the DAs amounts to the extraction of brain-behaviour associations that rely on their joint information captured by MoPoE-VAE joint latent space. We claim that this joint information can be related to the general psychopathology dimension introduced by Caspi and colleagues6,7. Thus, all retained brain-behaviour associations are considered transdignostic (see the complete listing in Supplemental S7).

In the following, for the sake of clarity, we only focus on these transdiagnostic associations whose ROIs are linked with at least the SRS, SCARED, SDQ-ha, and CBCL-wd core scores. Thus, the ROI reported in Fig. 3 are linked to 4, 5, 6, or 7 scores. These ROIs are interpreted as components of a transdiagnostic spatial support for mental disorders. The four selected scores assess social interaction (SRS), fear and anxiety (SCARED), hyperactivity (SDQ-ha), and depression (CBCL-wd). Such a variety of scores covers a wide range of psychiatric pathologies. Among these selected transdiagnostic regions, many belong to the pericallosal and cingulate regions. These regions, whether considered in area or in curvature, are consistently associated with each examined score: the associations between selected ROIs and scores show similar covariance. In the identified pericallosal and cingulate regions, a decrease in both area and curvature is associated with an increase in the SRS, SCARED, or CBCL-wd scores. However, the opposite is observed for the SDQ-ha score. Comparing Fig. 3b, c and d, we observe two disjoint sets of regions: in the former (thickness metric) the left and right occipital poles, and in the latter (curvature and area metrics) the cingulate regions. Interestingly, some ROIs are linked to the four core scores for all metrics: the right cingulate mid/posterior region (R.Ci.Mid.Post.), and left cingulate posterior dorsal gyrus (L.G.Ci.Post.Dors). Finally, the SDQ-ha associations always have opposite signs compared to the SRS, SCARED and CBCL-wd scores. Overall, the transdiagnostic regions described are mostly bilateral, and spatially contiguous.

Transdiagnostic-association spatial support in ASD and ADHD

In contrast with what we have presented so far, we will now look at all the transdiagnostic associations that are associated with a particular score as opposed to the four core scores. Our aim is to examine a specific pathology proxied by that particular score. We perform this analysis for two scores. First, the SRS score, which is considered as a proxy for ASD49. Although the SRS score alone may not be sufficient, clinicians often use it to determine a patient’s status and the severity of their condition. This score has a high correlation with diagnosis in datasets adhering to diagnosis-balanced inclusion criteria such as ABIDE I (SRS-1, 0.82), ABIDE II (SRS-1, 0.86 and SRS-2, 0.72), or EU-AIMS (SRS-2, 0.85)50,51. With the same reservations, we use the SDQ-ha score as a proxy for ADHD-related symptoms and diagnosis52. The retained associations can be found in Supplemental S7 and are summarised below.

Markers related to SRS (a–b) and SDQ-ha (c–d). The ROIs associated in thickness and area with these eCRF scores are displayed on an inflated cortical surface. Regions appear in either blue or red, indicating a negative or positive association, respectively. The following notations are used: L: left, R: right.

Markers related to SRS (a proxy of ASD)

In Figure 4a, b, we display all ROIs associated in thickness and area with the SRS score. Interestingly, the selected ROIs display a rather symmetrical pattern. With the thickness metric, the SRS appears to correlate positively with the bilateral occipital poles, bilateral pericallosal regions, and a right prefrontal region, and negatively with the bilateral temporal sulci and right postcentral region. With area metrics, the SRS appears to positively correlate with the left prefrontal cortex, left subcallosal gyrus and bilateral circular inferior insular sulci, and negatively with the bilateral cingulate and left parieto-temporal cortices.

Markers related to SDQ-ha (a proxy of ADHD)

In Figure 4c, d, we display all ROIs found to be associated in thickness and area with the SDQ-ha score. Once again the figure displays symmetrical patterns. With the thickness metric, the SDQ-ha appears to correlate positively with postcentral and superior parietal regions, including the left precuneus, and negatively with the central sulci, the cingulate and occipital cortices. With the area metric, the SDQ-ha appears to correlate positively with the bilateral parieto-temporal cortices and bilateral cingulate cortices, and negatively with the bilateral central sulci and right precentral gyrus. Notably, the central sulci appear to be affected by the SDQ-ha score in the same direction for both area and thickness.

Discussion

Here we report an interpretability method dedicated to deep learning-based integration models using mVAEs. We demonstrate its application in the study of the transdiagnostic dimension within the HBN cohort, integrating neuroimaging data and psychological assessments in an at-risk population with notable behavioural symptoms. Our method uses a stability selection procedure to retain associations and we investigate its effects. A sufficient number of models in the ensembling step seems to be the only necessary condition for achieving stability. Finally, with only a prior on the expected number of associations, our method enables the identification of stable associations between measures of the brain cortical surface and symptom scores.

Digital avatars can be utilised to create synthetic datasets for training and evaluating models, effectively addressing challenges such as data scarcity and bias in real-world datasets. They enable researchers to systematically control and manipulate various factors (e.g., symptoms, demographic information), facilitating the study of diseases with clustered symptomatology. Taking advantage of this controlled testing environment, digital avatar analysis can help evaluate and interpret a previously trained multi-view generative model in different clinical scenarios.

We take advantage of the versatile definition of the latent space in the MoPoE-VAE to choose a representation setting that naturally disentangles specific and shared sources of variation between view-specific and joint latent spaces. Other works have already identified the disentanglement achieved with this type of architecture16,17,53, but we apply it here to neuroimaging and electronic case report forms integration. We also leverage this source separation using our interpretation module based on digital avatars. By mitigating or eliminating confounding effects such as the MRI acquisition site in shared representations, we expect interpretations to be unaffected, without performing any standardisation or harmonisation of the data prior to learning. Moreover, the joint latent space that significantly correlates with age highlights how our models handle age information, although it is never explicitly provided. This contrasts with conventional approaches which use age residualisation.

Our framework based on the MoPoE-VAE can conveniently handle incomplete data, a common issue in multi-view integration. The requirement of complete data often significantly reduces the number of subjects that can be used and impairs the statistical power of most studies. This made it possible for us to use an openly available cohort with minimal missing data control while including nearly every available subject. This provided us with a substantial sample size collected from multiple acquisition sites which should improve reproducibility and replicability when employing such an approach in multi-view neuroimaging studies, aligning with state-of-the-art guidelines36,54,55.

We also show that MoPoE-VAE networks, when equipped with a stable interpretation module, can provide associations between variables of different views. This stable interpretation module can be configured with only one a priori parameter which is the expected number of associations (\(n_\text {select}=12\) here).

Transdiagnostic theories hypothesise a common risk factor for various psychiatric pathologies, rather than focusing solely on specific diagnostic categories (such as the DSM-V categorical diagnostic system)5. These transdiagnostic studies consider shared risk factors such as childhood trauma (which increases the risk of all psychiatric disorders) and genetic vulnerability factors (the alleles are often associated with increased predisposition to a number of psychiatric disorders). Some of them suggest the existence of a general psychopathology p-factor6 and examine its association with brain imaging to find potential biomarkers of these common mechanisms.

The proposed MoPoE-VAE model is trained on data from an at-risk population cohort in which subjects are assessed with questionnaires, expressing symptoms of several psychiatric syndromes (reported by SRS or SDQ-ha, etc.). The learned latent representations integrate all available information into shared and specific latent spaces. The shared representations contain multivariate variability linking multiple symptom scores to imaging. Thus, when examining regions associated with multiple symptom scores in the results section, we expect to capture regions reported in the transdiagnostic literature. Our findings are discussed in this regard below:

-

Associations in structural MRI: We highlight fairly symmetrical regions, mostly associated in area and curvature in the cingulate regions and in thickness in the occipital poles. This is in line with many studies that report structural alterations associated with transdiagnostic factors, such as changes in cortical thickness or grey matter volume of the cingulate and occipital cortices, as part of more global patterns56,57,58,59. Such findings have also been specifically highlighted in ASD39,60,61,62 or ADHD63,64,65 studies, as well as in studies jointly examining these two conditions66,67. In addition, grey matter in the occipital lobe has been specifically associated with increases in p-factor68,69,70.

-

Associations in functional MRI: Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have also already identified the cingulo-opercular network71 and the default mode network, supported in particular by the anterior cingulate areas72,73, as related to transdiagnostic factors. They have also associated the anterior/middle cingulate and occipital areas, among others, with the general p-factor74. The same observation has been made in studies of transdiagnostic populations75,76, particularly with ASD and ADHD patients67,77,78. It therefore comes as no surprise to find the cingulate as a transdiagnostic risk marker, given its highly associative role in the brain.

-

Associations in diffusion MRI: Finally, diffusion MRI studies have found using fractional anisotropy of cingulum white matter tracts that the cingulum is associated with transdiagnostic factors79. The cingulum is known to be involved in cognition and emotion processing80,81,82. As these functions are often altered in the expression of psychiatric symptoms, its implication in a common mechanism underlying several syndromes is very likely. Our findings support the hypothesis that cingulate and occipital regions and their related functional or structural networks are important in general psychopathology but they warrant further investigation.

The method described in this paper is a framework for interpreting the representation space learned by a deep integrative multi-view approach. We discussed the main benefits of its use and below we list a few perspectives concerning its limitations, with some general remarks on the integration of the ever-growing volume and variety of available data in neuroscience:

-

Effect size: In our transdiagnostic study, the stable associations found are characterised by rather small effect sizes. Reproducible brain-behaviour relationships with small effect sizes have already been reported55. Associating biological measures with behaviour comes with numerous challenges such as reliability issues, imprecision in biological measurements and imperfect behaviour scales83. This underlines the difficulty of exploring the common processes that hypothetically contribute to the etiology of multiple psychopathologies and this calls for a change in studies investigating p-factor or RDoC in a traditional, diagnostic-based setting. While individual effect sizes may be modest, the cumulative evidence supports the existence of transdiagnostic factors. One could expect an increase in the observed effect sizes by considering fMRI data instead of structural MRI. Association studies using fMRI offer numerous advantages, including direct measurement of brain activity and localisation of function. Current fMRI research shows strong associations compared to structural MRI55,84 and may be worth investigating using our proposed method.

-

Data harmonisation: Several recent works have shown that machine learning models are strongly biased by the MRI acquisition site and do not generalise well to MRI images from unseen sites85,86. This problem is due to differences in scanner manufacturers, specifications, settings, and hardware. While traditional residualisation techniques for removing the site effect marginally improve the performance of machine learning models, they do not bring any improvement for deep learning models87. In this work, we show that the influence of non-interest factors, in particular the site effect, can be effectively eliminated by disentangling modality-specific and joint latent representations. This modality-specific and joint variability disentanglement could be further improved using recent advances in the mVAE literature22. Nevertheless, data harmonisation remains a topic of ongoing research88,89. For example, the OpenBHB challenge90 on brain age prediction with site effect removal could bring new harmonisation techniques developed by the community.

-

Dimensional discrepancy of the views: The integrative capacity of mVAEs comes from modelling modality-specific and joint latent spaces. Handling views with a very different number of variables is an ongoing research question. For example, genotyping data may have millions of variables. Training an mVAE in such a setting is challenging. Intuitively, learned modality-specific latent spaces will have different sizes, somehow proportional to their input size, but this is not so clear for the joint representations. It would be possible to use pioneering work that defines a sparse multichannel VAE and leverages a variational dropout regularisation to identify an optimal number of joint latent dimensions20.

-

Replication: A replication study would enable us to determine the generalisability of our findings. In particular, it would be interesting to apply our approach to cohorts such as the Dunedin Longitudinal study6,69, the ABCD study91,92 or the Duke Neurogenic study68,74. These studies were not explicitly focused on transdiagnostic research, but their design, including comprehensive assessments with a multidisciplinary context, has provided valuable insights into the understanding of psychiatric disorders from a transdiagnostic perspective.

Data availibility

The data is accessible at https://zenodo.org/records/10987604, but requires prior authorisation. The data used to prepare this manuscript originate from Healthy Brain Network (HBN) cohort established by the Child Mind Institute (Project: https://healthybrainnetwork.org/, data portal: https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/cmi_healthy_brain_network).

Code availability

The code to reproduce the experiments and results is made publicly available at https://zenodo.org/records/10987502.

References

Williams, L. M. Special report: Precision psychiatry–are we getting closer?. (2022).

(American Psychiatric Association). A.P.A., Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, a division of American Psychiatric Association, 5th ed., (2013).

Stoyanov, D., Telles-Correia, D. & Cuthbert, B. N. The research domain criteria (RDoC) and the historical roots of psychopathology: A viewpoint. Eur. Psychiatry 57, 58–60 (2019).

Insel, T. et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 748–751 (2010).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Transdiagnostic psychiatry: A systematic review. World Psychiatry 18(2), 192–207 (2019).

Caspi, A. et al. The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders?. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2(2), 119–137 (2014) (PMID: 25360393).

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Fisher, H. L., Danese, A. & Moffitt, T. E. The general factor of psychopathology (p): Choosing among competing models and interpreting p. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 12(1), 53–82 (2023).

Wu, M. & Goodman, N. Multimodal generative models for scalable weakly-supervised learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 31 (eds Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc, 2018).

Shi, Y. et al. Variational mixture-of-experts autoencoders for multi-modal deep generative models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 32 (eds Wallach, H. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc, 2019).

Sutter,T., et al. Generalized multimodal ELBO. in 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021, OpenReview.net (2021).

Baltrušaitis,T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 41, pp. 423–443, (2019).

Rahaman, M. A., Garg, Y., Iraji, A., Fu, Z., Chen,J. & Calhoun, V. Two-dimensional attentive fusion for multi-modal learning of neuroimaging and genomics data, in 2022 IEEE 32nd International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), 1–6, IEEE, (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Deep multimodal fusion by channel exchanging. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 33 (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 4835–4845 (Curran Associates Inc, 2020).

Rahaman, M. A. et al. Deep multimodal predictome for studying mental disorders. Human Brain Mapping 44(2), 509–522 (2023).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. in 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014, Banff, AB, Canada, April 14–16, 2014, Conference Track Proceedings (Y. Bengio and Y. LeCun, eds.), (2014).

Wang, W., Yan, X., Lee, H. & Livescu, K. Deep Variational Canonical Correlation Analysis. arXiv:1610.03454 [cs], arXiv: 1610.03454. (2017).

Lee, M. & Pavlovic, V. Private-Shared Disentangled Multimodal VAE for Learning of Latent Representations. in CVPR. 1692–1700, (2021).

Kingma, D. P., et al. Semi-supervised learning with deep generative models, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, December 8-13 2014, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (Z. Ghahramani, M. Welling, C. Cortes, N. D. Lawrence, and K. Q. Weinberger, eds.), 3581–3589, (2014).

Suzuki, M., Nakayama, K. & Matsuo, Y. Joint multimodal learning with deep generative models. in 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2017, Toulon, France, April 24-26, 2017, Workshop Track Proceedings, OpenReview.net (2017).

Antelmi, L., et al. Sparse multi-channel variational autoencoder for the joint analysis of heterogeneous data. in Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (K. Chaudhuri and R. Salakhutdinov, eds.), vol. 97 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 302–311, PMLR, 09–15 Jun (2019).

Daunhawer, I., Sutter, T. M., Chin-Cheong, K., Palumbo, E. & Vogt, J. E. On the limitations of multimodal vaes. in The Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2022, Virtual Event, April 25-29, 2022, OpenReview.net (2022).

Daunhawer, I., Sutter, T. M., Marcinkevičs, R. & Vogt, J. E. Self-supervised Disentanglement of Modality-Specific and Shared Factors Improves Multimodal Generative Models. in Pattern Recognition (Z. Akata, A. Geiger, and T. Sattler, eds.), vol. 12544, 459–473, (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Palumbo, E., Daunhawer, I. & Vogt, J. E. MMVAE+: Enhancing the Generative Quality of Multimodal VAEs without Compromises. in ICLR, (Mar. 2022).

Ambroise, C., Grigis, A., Duchesnay,E. & Frouin, V. Multi-view variational autoencoders allow for interpretability leveraging digital avatars: Application to the hbn cohort, in 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (2023).

Kendall, A. & Gal, Y. What uncertainties do we need in Bayesian deep learning for computer vision? In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Gyawali, P. K., Liu, X., Zou, J. & He, Z. Ensembling improves stability and power of feature selection for deep learning models, in Proceedings of the 17th Machine Learning in Computational Biology meeting (D. A. Knowles, S. Mostafavi, and S.-I. Lee, eds.), vol. 200 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 33–45, PMLR, 21–22 Nov (2022).

Petiton, S., Grigis, A., Dufumier, B. & Duchesnay, E. How and why does deep ensemble coupled with transfer learning increase performance in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia classification? in ISBI, (2024).

Labus, J. S. et al. Multivariate morphological brain signatures predict patients with chronic abdominal pain from healthy control subjects. PAIN 156(8), 1545–1554 (2015).

Baldassarre, L., Pontil, M. & Mourão-Miranda, J. Sparsity is better with stability: Combining accuracy and stability for model selection in brain decoding. Front. Neurosci. 11, 62 (2017).

Ing, A., Sämann, P. G., Chu, C., Tay, N., Biondo, F., Robert, G., Jia, T., Wolfers, T., Desrivières, S., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A. L. W., Bromberg, U., Büchel, C., Conrod, P., Fadai, T., Flor, H., Frouin, V., Garavan, H., Spechler, P. A., Gowland, P., Grimmer, Y., Heinz, A., Ittermann, B., Kappel, V., Martinot, J.-L., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Millenet, S., Nees, F., van Noort, B., Orfanos, D. P., Martinot, M.-L. P., Penttilä, J., Poustka, L., Quinlan, E. B., Smolka, M. N., Stringaris, A., Struve, M., Veer, I. M., Walter, H., Whelan, R., Andreassen, O. A., Agartz, I., Lemaitre, H., Barker, E. D., Ashburner, J., Binder, E., Buitelaar, J., Marquand, A., Robbins, T. W., Schumann, G., & IMAGEN Consortium. Identification of neurobehavioural symptom groups based on shared brain mechanisms, Nat. Human Behav., 3, 1306–1318 (2019).

Mihalik, A. et al. Multiple holdouts with stability: Improving the generalizability of machine learning analyses of brain-behavior relationships. Biol. Psychiatry 87(4), 368–376 (2020).

Cao, K. L., Boitard, S. & Besse, P. Sparse PLS discriminant analysis: Biologically relevant feature selection and graphical displays for multiclass problems. BMC Bioinform. 12, 253 (2011).

Helmer, M. et al. On the stability of canonical correlation analysis and partial least squares with application to brain-behavior associations. Commun. Biol. 7, 217 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. Stability test of canonical correlation analysis for studying brain-behavior relationships: The effects of subject-to-variable ratios and correlation strengths. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42(8), 2374–2392 (2021).

Nakua, H., Yu, J.-C., Abdi, H., Hawco, C., Voineskos, A., Hill, S., Lai, M.-C., Wheeler, A. L., McIntosh, A. R., & Ameis, S. H. Comparing the stability and reproducibility of brain-behaviour relationships found using canonical correlation analysis and partial least squares within the ABCD sample, bioRxivorg. (2023).

Vieira, S. et al. Multivariate brain-behaviour associations in psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 231 (2024).

Meinshausen, N. & Bühlmann, P. Stability selection. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 72(4), 417–473 (2010).

Alexander, L. M. et al. An open resource for transdiagnostic research in pediatric mental health and learning disorders. Sci. Data 4, 170181 (2017).

Mihailov, A. et al. Cortical signatures in behaviorally clustered autistic traits subgroups: A population-based study. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 207 (2020).

Dale, A. M. et al. Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 9(2), 179–194 (1999).

Rosen, A. F. G. et al. Quantitative assessment of structural image quality. Neuroimage 169, 407–418 (2018).

Destrieux, C. et al. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53(1), 1–15 (2010).

Bryk, A. & Raudenbush, S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences (SAGE Publications, 1992).

Kiureghian, A. D. & Ditlevsen, O. Aleatory or epistemic? Does it matter?. Struct.Safety 31(2), 105–112 (2009).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning, in Proceedings of The 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (M. F. Balcan and K. Q. Weinberger, eds.), vol. 48 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, (New York, New York, USA), 1050–1059, PMLR, 20–22 Jun (2016).

Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A. & Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc, 2017).

Kriegeskorte, N. et al. Representational similarity analysis—connecting the branches of systems neuroscience. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2, 249 (2008).

Sechidis, K., et al., On the stratification of multi-label data, in Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. 145–158 (Springer, 2011).

Constantino, J. N. et al. Validation of a brief quantitative measure of autistic traits: Comparison of the social responsiveness scale with the autism diagnostic interview-revised. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 33(4), 427–433 (2003).

Di Martino, A. et al. The autism brain imaging data exchange: Towards a large-scale evaluation of the intrinsic brain architecture in autism. Mol. Psychiatry 19(6), 659–667 (2014).

Loth, E. et al. The EU-AIMS longitudinal European autism project (LEAP): Design and methodologies to identify and validate stratification biomarkers for autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Autism 8(1), 24–24 (2017).

Goodman, R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 38(5), 581–586 (1997).

Qiu, L., Lin,L. & Chinchilli, V. M. Variational Interpretable Learning from Multi-view Data, (2022). arXiv:2202.13503 [cs, stat].

Klapwijk, E. T., van den Bos, W., Tamnes, C. K., Raschle, N. M. & Mills, K. L. Opportunities for increased reproducibility and replicability of developmental neuroimaging. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 47, 100902 (2021).

Marek, S. et al. Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature 603, 654–660 (2022).

Goodkind, M. et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 305–315 (2015).

Clementz, B. A. et al. Identification of distinct psychosis biotypes using brain-based biomarkers. Am. J. Psychiatry 173(4), 373–384 (2016) (PMID: 26651391).

Yin, S. et al. Shared and distinct patterns of atypical cortical morphometry in children with autism and anxiety. Cereb. Cortex 32, 4565–4575 (2022).

Parkes, L. et al. Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychopathology explain individuals’ unique deviations from normative neurodevelopment in brain structure. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 232 (2021).

Oblak, A. L., Gibbs, T. T. & Blatt, G. J. Decreased gabab receptors in the cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus in autism. J. Neurochem. 114(5), 1414–1423 (2010).

Chien, Y.-L., Chen, Y.-C. & Gau, S.S.-F. Altered cingulate structures and the associations with social awareness deficits and cntnap2 gene in autism spectrum disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 31, 102729 (2021).

Ecker, C. et al. Interindividual differences in cortical thickness and their genomic underpinnings in autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 179(3), 242–254 (2022) (PMID: 34503340).

Amico, F., Stauber, J., Koutsouleris, N. & Frodl, T. Anterior cingulate cortex gray matter abnormalities in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 191(1), 31–35 (2011).

He, N. et al. Neuroanatomical deficits correlate with executive dysfunction in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 600, 45–49 (2015).

Bayard, F. et al. Distinct brain structure and behavior related to ADHD and conduct disorder traits. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 3020–3033 (2020).

Rommelse, N., Buitelaar, J. K. & Hartman, C. A. Structural brain imaging correlates of ASD and ADHD across the lifespan: a hypothesis-generating review on developmental asd-adhd subtypes. J. Neural Transm. 124, 259–271 (2017).

Lukito, S. et al. Comparative meta-analyses of brain structural and functional abnormalities during cognitive control in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Med. 50, 894–919 (2020).

Romer, A. L. et al. Structural alterations within cerebellar circuitry are associated with general liability for common mental disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1084–1090 (2018).

Romer, A. L. et al. Replicability of structural brain alterations associated with general psychopathology: Evidence from a population-representative birth cohort. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3839–3846 (2021).

Romer, A. L. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Associations between brain structural alterations, executive dysfunction, and general psychopathology in a healthy and cross-diagnostic adult patient sample. Biol. Psychiatry Global Open Sci. 2(1), 17–27 (2022).

Sheffield, J. M. et al. Transdiagnostic associations between functional brain network integrity and cognition. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 605–613 (2017).

Gong, Q. et al. Network-level dysconnectivity in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis: Dissociating transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific alterations. Neuropsychopharmacology 42(4), 933–940 (2016).

MacNamara, A., Klumpp, H., Kennedy, A. E., Langenecker, S. A. & Phan, K. L. Transdiagnostic neural correlates of affective face processing in anxiety and depression. Depress. Anxiety 34(7), 621–631 (2017).

Elliott, M. L., Romer, A., Knodt, A. R. & Hariri, A. R. A connectome-wide functional signature of transdiagnostic risk for mental illness. Biol. Psychiatry 84(6), 452–459 (2018) (Translating Biology to Treatment in Schizophrenia).

Feldker, K. et al. Transdiagnostic brain responses to disorder-related threat across four psychiatric disorders. Psychol. Med. 47, 730–743 (2017).

Tong, X. et al. Transdiagnostic connectome signatures from resting-state FMRI predict individual-level intellectual capacity. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 367 (2022).

Bush, G. et al. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by FMRI and the counting STROOP. Biol. Psychiat. 45(12), 1542–1552 (1999).

D’Cruz, A.-M., Mosconi, M. W., Ragozzino, M. E., Cook, E. H. & Sweeney, J. A. Alterations in the functional neural circuitry supporting flexible choice behavior in autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e916–e916 (2016).

Stefanik, L. et al. Brain-behavior participant similarity networks among youth and emerging adults with schizophrenia spectrum, autism spectrum, or bipolar disorder and matched controls. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 1180–1188 (2018).

Bush, G., Luu, P. & Posner, M. I. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4(6), 215–222 (2000).

Vogt, B. A., Finch, D. M. & Olson, C. R. Functional heterogeneity in cingulate cortex: The anterior executive and posterior evaluative regions. Cereb. Cortex 2, 435–443 (1992).

Denson, T. F., Pedersen, W. C., Ronquillo, J. & Nandy, A. S. The angry brain: Neural correlates of anger, angry rumination, and aggressive personality. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21, 734–744 (2009).

Najar, D., Dichev, J. & Stoyanov, D. Towards new methodology for cross-validation of clinical evaluation scales and functional MRI in psychiatry. J. Clin. Med. 13(15), 4363 (2024).

Oblong, L. M., Llera, A., Mei, T., Haak, K., Isakoglou, C., Floris, D. L., Durston, S., Moessnang, C., Banaschewski, T., Baron-Cohen, S., Loth, E., Dell’Acqua, F., Charman, T., Murphy, D. G. M., Ecker, C., Buitelaar, J. K., Beckmann, C. F., Ahmad, J., Ambrosino, S., Auyeung, B., Banaschewski, T., Baron-Cohen, S., Baumeister, S., Beckmann, C. F., Bölte, S., Bourgeron, T., Bours, C., Brammer, M., Brandeis, D., Brogna, C., de Bruijn, Y., Buitelaar, J. K., Chakrabarti, B., Charman, T., Cornelissen, I., Crawley, D., Dell’Acqua, F., Dumas, G., Durston, S., Ecker, C., Faulkner, J., Frouin, V., Garcés, P., Goyard, D., Ham, L., Hayward, H., Hipp, J., Holt, R. J., Johnson, M. H., Jones, E. J. H., Kundu, P., Lai, M.-C., D’ardhuy, X. L., Lombardo, M. V., Loth, E., Lythgoe, D. J., Mandl, R., Marquand, A., Mason, L., Mennes, M., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Moessnang, C., Mueller, N., Murphy, D. G. M., Oakley, B., O’Dwyer, L., Oldehinkel, M., Oranje, B., Pandina, G., Persico, A. M., Price, J., Rausch, A., Ruggeri, B., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Sabet, J., Sacco, R., Cáceres, A. S. J., Simonoff, E., Spooren, W., Tillmann, J., Toro, R., Tost, H., Waldman, J., Williams, S. C. R., Wooldridge, C., Ilioska, I., Mei, T., Zwiers, M. P., Forde, N. J. & The EU-AIMS LEAP Group, Linking functional and structural brain organisation with behaviour in autism: a multimodal EU-AIMS longitudinal european autism project (LEAP) study, Mol. Autism, 14 (1), 32, (2023).

Glocker,B., Robinson, R., Castro, D. C., Dou, Q. & Konukoglu,E. Machine learning with multi-site imaging data: An empirical study on the impact of scanner effects. (2019).

Wachinger, C., Rieckmann, A. & Pölsterl, S. Detect and correct bias in multi-site neuroimaging datasets. Med. Image Anal. 67, 101879 (2021).

Dufumier, B., Gori, P., Petiton, S., Louiset, R., Mangin, J.-F., Grigis, A. & Duchesnay, E. Exploring the potential of representation and transfer learning for anatomical neuroimaging: Application to psychiatry. Working paper or preprint, (Feb, 2024).

Dinsdale, N. K., Jenkinson, M. & Namburete, A. I. Deep learning-based unlearning of dataset bias for MRI Harmonisation and confound removal. Neuroimage 228, 117689 (2021).

Bashyam, V. M., Doshi, J., Erus, G., Srinivasan, D., Abdulkadir, A., Singh, A., Habes, M., Fan, Y., Masters, C. L., Maruff, P., Zhuo, C., Völzke, H., Johnson, S. C., Fripp, J., Koutsouleris, N., Satterthwaite, T. D., Wolf, D. H., Gur, R. E., Gur, R. C., Morris, J. C., Albert, M. S., Grabe, H. J., Resnick, S. M., Bryan, N. R., Wittfeld, K., Bülow, R., Wolk, D. A., Shou, H., Nasrallah, I. M., Davatzikos, C. & The iSTAGING and PHENOM consortia. Deep generative medical image harmonization for improving cross-site generalization in deep learning predictors. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 55 (3), 908–916 (2022).

Dufumier, B. et al. Openbhb: A large-scale multi-site brain MRI data-set for age prediction and debiasing. Neuroimage 263, 119637 (2022).

Casey, B. J. et al. The adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: Imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 43–54 (2018).

Karcher, N. R. & Barch, D. M. The ABCD study: Understanding the development of risk for mental and physical health outcomes. Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 131–142 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully thank Benoit Dufumier and Raphael Vock for reviewing the manuscript and providing their thoughts on how to improve it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A., V.F. and A.G. designed the experiments, C.A. conducted the experiments, V.F. and A.G. provided critical feedback, V.F. supervised the project, A.G. pre-processed the data, C.A., V.F. and A.G. wrote the manuscript, C.A., V.F., A.G. and J.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The other authors declare no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ambroise, C., Grigis, A., Houenou, J. et al. Interpretable and integrative deep learning for discovering brain-behaviour associations. Sci Rep 15, 2312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85032-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85032-5