Abstract

TB/HIV co-infection is associated with poorer treatment outcomes compared to TB alone. This study assessed the TB treatment success rate and its predictors among TB/HIV co-infected patients in East and North Eastern Uganda. A retrospective cohort design was used, involving 324 patients treated between July 2019 and July 2021 at three regional referral hospitals. Treatment success, defined as completing therapy with or without bacteriologic confirmation, was achieved by 71.9% of patients (95% CI 67–77%). Loss to follow-up was 12%, mortality 9.9%, treatment failure 0.3%, and 5.2% were not evaluated. Patients lacking sputum monitoring at five months were significantly less likely to achieve treatment success (aRR 0.48, 95% CI 0.34–0.66). These findings underscore the importance of effective follow-up to improve outcomes for TB/HIV co-infected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is still a significant global public health concern1. In 2022, more than 10 million people developed TB, and about 1.4 million people died from TB2. Almost 90% of global TB cases each year occur in 30 high burden TB-burden countries in Africa, and about 87% of TB patients in this region are HIV co-infected2,3. Uganda is one of the high TB burden countries; about 86,000 people developed TB in 2019, of which 40% had TB/HIV co-infection4,5.

Early diagnosis and successful treatment of TB with a six-month course of TB drugs effectively reduces TB transmission and averts death6. Between 2000 and 2020, early diagnosis and treatment of TB were estimated to have averted 66 million deaths2. Despite widespread access to TB prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care services, the global treatment success rate was 85% among HIV-negative people in 2019 and 76% for HIV-positive people7. In Africa, the treatment success rate stands at 78.9% and is even lower for those with HIV/TB co-infection3,8. Studies have revealed various factors that affect TB treatment outcomes, including age, sex,, education, employment and healthcare systems factors such as distance from patients’ residence to the facility, Cotrimoxazole Preventive therapy (CPT) initiation, patient follow-up at five months, baseline weight, sputum smear positivity, previous TB treatment, late HIV stage, and history of opportunistic infections3,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all people living with HIV be screened for TB using a clinical algorithm and that TB treatment is started in HIV-co-infected patients as soon as active TB has been diagnosed2,6. WHO also recommends collaboration of HIV/TB activities to reduce the burden of TB among HIV-infected patients through intensifying case finding, isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT), providing TB treatment to those with active TB and ensuring TB infection control in health care and congregate settings2. As such, the Ministry of Health in Uganda recommends using a one-stop center for delivering integrated TB/HIV services; that is a TB/HIV co-infected patient receives TB/HIV services at the same clinic from the same healthcare team16. Despite implementing these recommendations and improving access to TB prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care, Uganda has a low TB treatment success rate of 70% among TB/HIV co-infected patients5. This treatment success rate is below the desired WHO target of ≥ 90%5. Successful treatment of TB is an important indicator for measuring the optimal performance of TB control programs and achieving the goals of the End TB Strategy17. Moreover, unsuccessful treatment of TB has been associated with the emergence of drug resistance, transmission of TB at the household and community levels, mortality and complications in TB patients18. In this study, we assessed the treatment success rate and predictors of successful TB outcomes among TB/HIV co-infected patients in East and North Eastern Uganda.

Methods

Study design and population

This two-year retrospective cohort study (July 2019–July 2021) focused on TB/HIV co-infected patients undergoing TB treatment at Mbale, Soroti, and Moroto Regional Referral Hospitals (RRHs) in Eastern and North Eastern Uganda. Data were obtained from the TB unit registers of these public hospitals, which offer free healthcare. Mbale and Soroti RRHs serve as referral and teaching hospitals in Eastern Uganda, while Moroto RRH, located in the Karamoja sub-region of North Eastern Uganda, serves a population of 1.2 million and reports over 5500 TB cases annually—equivalent to a notification rate of approximately 450 per 100,000, significantly higher than the national average of 213 per 100,00019. The study included HIV patients receiving TB treatment in the TB wards of these facilities.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included HIV patients aged 15 years and above, diagnosed with active TB disease per Uganda’s national clinical guidelines20, and on anti-TB treatment between July 2019 and July 2021, including those transferred in to continue treatment. Excluded were patients who had taken less than four weeks of anti-TB treatment or were transferred out to another facility with unknown treatment outcomes.

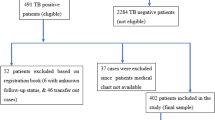

Sample size estimation and sampling

Using the Kish Leslie formula21, we assumed a 70% proportion of successful TB treatment outcomes among TB/HIV co-infected patients reported by the Ministry of Health, Uganda5 and a precision of 5%. This gave us a total sample size of 324 participants. A disproportionate stratified random sample of 108 TB/HIV co-infected patients were selected from each of the three regional referral hospitals, with the sample not being proportional to the distribution within the population of interest. A total of 108 TB/HIV co-infected patients were recruited from each of the selected regional referral hospitals.

Study variables and measurements

The primary outcome variable was TB treatment success rate, defined as the proportion of TB cases registered between July 2019 and July 2021 that completed treatment, either as “cured” or “treatment completed,” based on WHO’s 2013 definitions. Successful outcomes included cured and treatment completed, while unsuccessful outcomes included treatment failure, loss to follow-up, death, or not evaluated22.

Dependent variables

Cured: Bacteriologically confirmed TB patient who was smear- or culture-negative at treatment completion and on at least one prior occasion.

Treatment Completed: Patient completed treatment without bacteriologic confirmation of cure.

Treatment Failed: Patient with positive sputum smear or culture at month five or later or who became smear-positive during treatment.

Died: Patient who died before or during treatment.

Loss to Follow-up: Patient interrupted treatment for two consecutive months or more.

Not Evaluated: Treatment outcome unknown, including cases transferred out.

Independent variables

Socio-Demographic Characteristics: Age (categorized into six groups), sex, residence (urban or rural), and distance to the facility (< 5 km or ≥ 5 km).

Clinical Characteristics: Baseline weight (< 49.6 kg or ≥ 49.6 kg), TB classification (Extra-pulmonary TB, Pulmonary Bacteriologically Confirmed TB, or Pulmonary Clinically Diagnosed TB), patient type (new or retreatment), transfer category, follow-up at five months, WHO HIV clinical stage (1–4), CD4 count (< 200 or ≥ 200 cells/mm2), and medication-related factors (ART and Cotrimoxazole Preventive Therapy initiation).

All variables were measured following the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program guidelines of Uganda.

Data abstraction

Data were extracted from TB registers using a structured data abstraction form to capture treatment outcomes (cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, loss to follow-up, died, or not evaluated), along with sociodemographic, clinical, and healthcare system-related factors. The forms were pre-tested on three patients who had completed anti-TB treatment to ensure accuracy and ease of use, with ambiguous questions revised to align with the research objectives.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.0. Categorical variables were summarized as proportions, and continuous variables as means (standard deviation) or medians (interquartile range), as appropriate. The TB treatment success rate was calculated as the proportion of patients who completed treatment, with or without bacteriologic confirmation, among all cases registered between July 2019 and July 2021. Modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors was used for multivariable analysis. Variables with a p-value < 0.2 in bivariable analysis, those known from the literature, and plausible but not significant variables were included in the multivariable model to estimate risk ratios for treatment success.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 324 TB/HIV co-infected patients included in this study, more than half (53.4% [173/324]) were males. A quarter (28.5% [92/324]) were in the age group of (35–44) years and the mean age ± standard deviation for all participants was 38.2 ± 13.2 years. Regarding the distance from patients’ residence 230/100,000 to the facility, (64.2% [206/324]) lived within a 5 km radius from their respective health facilities. A greater percentage (71.8% [232/323]) resided in urban areas. Details are in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

The majority (89.8% [290/323]) of the TB/HIV co-infected patients were newly diagnosed TB cases, and two-thirds 68.5% (222/324) had pulmonary bacteriologically confirmed TB. Over 50% were in WHO HIV clinical stage 3, followed by 33.1% in stage 1, 8.3% in stage 4 and only 4.2% in stage 2. 52.4%. a high proportion (68.7%) of our participants had a CD4 count ≥ 200 cells/ mm3. Among those on treatment, more than half (50.5% [162/321]) had unmonitored sputum at five months, and amongst those whose sputum was monitored at 5 months, almost all (99.4% [158/159]) had negative sputum results. More than two-thirds of these patients were initiated on CPT, and almost 90% started treatment and completed it from the health facility where they were originally initiated. A greater proportion (87.9% [284/323]) were enrolled on ART. Details are in Table 2.

Treatment outcomes

Of the 324 TB/HIV co-infected patients, 41.0% (133/324) were cured, 30.9% (100/324) completed treatment, 12.7% (41/324) were lost to follow-up, 0.3% (1/324) had treatment failure, 9.9% (32/324) died, and 5.2% (17/324) not evaluated (Fig. 1). Overall, the treatment success rate among our participants was 71.9%, which comprises patients who cured (41.0%) and those that had completed treatment (30.9%).

Predictors of TB treatment success rate

Participants who were not followed up for sputum monitoring at five months had 52% less likelihood of achieving TB treatment success than those who were followed up at five months (aRR 0.48; 95% CI 0.34–0.66) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the TB treatment success rate and its predictors among TB/HIV co-infected patients at three regional referral hospitals in Eastern and North Eastern Uganda.

The overall TB treatment success rate between July 2019 and July 2021 in our study was 71.9% which was lower than that reported in a study done in eastern Uganda (81.1%)23 and other studies conducted in Africa; Northwest Ethiopia 77.3%24, and 80.5%25, South Africa 82.2%26, Cameroon 78.6%27, India 84.2%28. The lower TB treatment success rate in our study could be attributed to the high death rate (9.9%) and high loss to follow-up (12.5%) .

On the other hand, the TB treatment success rate in our study was higher than that reported in studies conducted in Southwest Ethiopia 30.3%29, Nigeria 48.8%30, Ghana 64.0%31 and Cameroon 60.8%32. This discrepancy might be due to differences in number of study participants involved and the TB treatment outcome definitions used in the various studies. Nevertheless, the TB treatment success rate registered in our study was comparable to the national TB treatment success rate of 70% among the TB/HIV co-infected patients reported by the Ministry of Health, Uganda5. However, our finding is far below the WHO End TB strategy success rate of ≥ 90%33.

In this study, we found that patient follow-up at five months for sputum monitoring was a predictor of TB treatment success. Patients who were not followed up at five months had 52% less likelihood of achieving TB treatment success than those followed up at five months. Another study conducted in Ethiopia also revealed that no follow-up of TB patients is associated with poor treatment outcomes34. At 5 months, patients are monitored for TB treatment adherence and provided with adherence counselling sessions if applicable. Patients who are not followed-up at 5 months could get lost during the course of the treatment, fail to complete their treatment or default treatment which may lead to death of the patient because of missing out on the adherence counselling sessions at 5 months.

A greater proportion of the patients within a 5 km radius had successful treatment outcomes than those who lived far away from the hospital. This finding was supported by a study conducted in Uganda35 and another study in Ethiopia36. Those living within a 5 km radius of a health facility have easy access to TB treatment services; therefore, providing more access points by rolling out treatment points, including outreach points to distant populations, would improve treatment outcomes. The current setup enables those living near the facility to refill their medicines easily, and those far away miss their appointments for refills. Consideration to build TB/HIV treatment capacity at HCIIs and HCIIIs at parish and sub-county levels, respectively, to reduce the distance from home to health facilities is necessary.

In our study, WHO HIV clinical stage, type of TB case, TB classifications were not significantly associated with TB treatment outcomes as revealed in other studies38,39,40. This could be attributed to our small sample size which wasn’t powered enough to detect these differences.

Study limitations

Our study relied purely on secondary data from TB registers and other medical documentation, thus missing and inaccurate data could not be avoided. Furthermore, the TB register does not capture data on variables like nutritional status, education status, marital status, and employment status, therefore, these important predictor variables were not used to assess treatment outcomes.

Some data on CD4 count status were missing due to occasional breakdowns in the CD4 count machine. The high loss to follow-up and the COVID-19 lockdown measures could have affected our results, for instance, we were not able to confirm COVID-19-related deaths from another source document other than the TB register. Additionally, the use of the disproportionate stratified random sampling method could have also affected our findings.

Conclusion

The TB treatment success rate among the TB/HIV co-infected patients in our study was lower than the desired WHO target of ≥ 90%. Additionally, our study also highlighted the importance of patient follow-up at month five as a significant predictor of TB/HIV treatment success. The findings underscore the need for sustained and consistent follow up at 5 months to improve TB patient’s treatment outcomes.

We think that in order to enhance follow-up, it is crucial to implement targeted interventions such as regular reminders for clinic visits, mobile health support, and closer coordination between TB/HIV care providers. Additionally, providing psychosocial support and addressing barriers to healthcare access, such as transportation or financial constraints, can help ensure continuity of care.

The risks associated with no follow-up include higher rates of treatment failure, loss to follow-up, and mortality, which may be exacerbated by co-infection with HIV. Missing follow-up at month five may increase the likelihood of undiagnosed treatment failure and complicate the management of both TB/HIV, ultimately leading to poorer outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021: Supplementary Material. (2022).

Chakaya, J. et al. Global tuberculosis Report 2020–Reflections on the global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 113, S7–S12 (2021).

Teferi, M. Y. et al. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and predictors in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (20), 10678 (2021).

World Health Organization. WHO global lists of high burden countries for tuberculosis (TB), TB/HIV and multidrug/rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB), 2021–2025: background document. (2021).

Oyediran, K. et al. Quality of Tuberculosis Services Assessment in Uganda (2020).

Harding, E. WHO global progress report on tuberculosis elimination. Lancet Respir. Med. 8 (1), 19 (2020).

Global tuberculosis report. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (2020).

Chaves Torres, N. M., Quijano Rodríguez, J. J., Porras Andrade, P. S., Arriaga, M. B. & Netto, E. M. Factors predictive of the success of tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 14 (12), e0226507 (2019).

Mumbe, J. M., Nzioki, J. M., Mutai, J. & Ndiritu, A. K. Socio-demographic and economic factors influencing adherence to TB Treatment in Mwingi East Sub-county, Kitui County, Kenya. Afr. J. Health Sci. 33 (6), 17–26 (2020).

Gadoev, J. et al. Factors associated with unfavorable treatment outcomes in new and previously treated TB patients in Uzbekistan: a five year countrywide study. PloS One. 10 (6), e0128907 (2015).

Gebrezgabiher, G. et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short course and factors affecting outcome in southern Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. PLoS One. 11 (2), e0150560 (2016).

Waitt, C. & Squire, S. A systematic review of risk factors for death in adults during and after tuberculosis treatment. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 15 (7), 871–885 (2011).

Mbatchou Ngahane, B. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of tuberculosis in Douala, Cameroon: a 7-year retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 20 (12), 1609–1614 (2016).

Wobudeya, E. et al. Outcomes of empiric treatment for pediatric tuberculosis, Kampala, Uganda, 2010–2015. BMC Public. Health. 19 (1), 1–6 (2019).

Tola, A., Minshore, K. M., Ayele, Y. & Mekuria, A. N. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among TB patients attending public hospitals in Harar town, Eastern Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2019 (2019).

Izudi, J., Tamwesigire, I. K. & Bajunirwe, F. Explaining the successes and failures of tuberculosis treatment programs; a tale of two regions in rural eastern Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 1–10 (2019).

Lönnroth, K. & Raviglione, M. The WHO’s new end TB strategy in the post-2015 era of the sustainable development goals. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 110 (3), 148–150 (2016).

Izudi, J., Okello, G. & Bajunirwe, F. Low treatment success rate among previously treated persons with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 32, 100375 (2023).

Kasozi, W. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards tuberculosis: results of a community-based survey in the Karamoja subregion, North Eastern Uganda. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 2489 (2024).

Uganda Clinical Guidelines. https://health.go.ug/sites/default/files/Uganda%20Clinical%20Guidelines%202016_FINAL.pdf (2016).

Rajbhandari, B. Sample size calculation (2021).

Eurosurveillance editorial team C. WHO revised definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis. In European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (2013).

Izudi, J., Tamwesigire, I. K. & Bajunirwe, F. Treatment success and mortality among adults with tuberculosis in rural eastern Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public. Health. 20 (1), 501 (2020).

Sinshaw, Y., Alemu, S., Fekadu, A. & Gizachew, M. Successful TB treatment outcome and its associated factors among TB/HIV co-infected patients attending Gondar University Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 17 (1), 1–9 (2017).

Balcha, T. T., Skogmar, S., Sturegård, E., Björkman, P. & Winqvist, N. Outcome of tuberculosis treatment in HIV-positive adults diagnosed through active versus passive case-finding. Glob. Health Action. 8 (1), 27048 (2015).

Jacobson, K. B., Moll, A. P., Friedland, G. H. & Shenoi, S. V. Successful tuberculosis treatment outcomes among HIV/TB coinfected patients down-referred from a district hospital to primary health clinics in rural South Africa. PLoS One. 10 (5), e0127024 (2015).

Tanue, E. A., Nsagha, D. S., Njamen, T. N. & Assob, N. J. C. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and its associated factors among people living with HIV and AIDS in Fako Division of Cameroon. PLoS One. 14 (7), e0218800 (2019).

Tripathi, S. B. & Kapadia, V. K. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis in HIV seropositive patients: an experience of Southeast Region of Ahmedabad. Natl. J. Community Med. 6 (04), 462–465 (2015).

Teshome Kefale, A. & Anagaw, Y. K. Outcome of tuberculosis treatment and its predictors among HIV infected patients in southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2017:161–169 .

Ofoegbu, O. S. & Odume, B. B. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at National Hospital Abuja Nigeria: a five year retrospective study. South. Afr. Fam. Pract. 57 (1), 50–56 (2015).

Ansa, G. A., Walley, J. D., Siddiqi, K. & Wei, X. Assessing the impact of TB/HIV services integration on TB treatment outcomes and their relevance in TB/HIV monitoring in Ghana. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 1 (1), 1–8 (2012).

Agbor, A. A. et al. Factors associated with death during tuberculosis treatment of patients co-infected with HIV at the Yaoundé Central Hospital, Cameroon: an 8-year hospital-based retrospective cohort study (2006–2013). PLoS One. 9 (12), e115211 (2014).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis and Patient Care. (2017).

Birhane, M., Mekonnen, S., Dingeta, T. & Teklemariam, Z. Loss to follow-up tuberculosis treatment and associated factors among adults attending at public health facilities in Warder District, Somali Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. Front. Public. Health 11. (2023).

Robsky, K. O. et al. Spatial distribution of people diagnosed with tuberculosis through routine and active case finding: a community-based study in Kampala, Uganda. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 9, 1–10 (2020).

Tesema, T., Seyoum, D., Ejeta, E. & Tsegaye, R. Determinants of tuberculosis treatment outcome under directly observed treatment short courses in Adama City, Ethiopia. PloS One. 15 (4), e0232468 (2020).

Vijay, S., Kumar, P., Chauhan, L. S., Narayan Rao, S. V. & Vaidyanathan, P. Treatment outcome and mortality at one and half year follow-up of HIV infected TB patients under TB control programme in a district of South India. PLoS One. 6 (7), e21008 (2011).

Hayibor, K. M., Bandoh, D. A., Asante-Poku, A. & Kenu, E. Predictors of adverse TB treatment outcome among TB/HIV patients compared with non-HIV patients in the greater accra regional hospital from 2008 to 2016. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2020, 1097581 (2020).

Tola, A., Minshore, K. M., Ayele, Y. & Mekuria, A. N. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and associated factors among TB patients attending public hospitals in Harar Town, Eastern Ethiopia: A five-year retrospective study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2019, 1503219 (2019).

Akanbi, K. et al. Predictors of tuberculosis treatment success among HIV-TB co-infected patients attending major tuberculosis treatment sites in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 32(Suppl 1) (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank our dear research assistants for the great work they did during the data abstraction process.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.O, D.B, P.O.O, D.M, and R.N conceived, designed, analyzed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. D.O, J.K.B.M, B.W, J.P.A were instrumental in data analysis, interpretation of the data and drafting of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained ethical approval and a waiver of informed consent from the Research and Ethics Committee of Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, approval number MRRH-2021-80. All study procedures were done in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written administrative authorisation to collect data from the Regional Referral Hospitals was obtained from the administration of the selected Regional Referral Hospitals. Confidentiality of the participants’ information was maintained, and data were secured in a locked cupboard and computer with a password.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Omara, G., Bwayo, D., Mukunya, D. et al. Tuberculosis treatment success rate and its predictors among TB HIV co-infected patients in East and North Eastern Uganda. Sci Rep 15, 5532 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85039-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85039-y