Abstract

Anhedonia, a core symptom of depression, has been defined as the loss of pleasure or lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli. Considering the relevance of alpha asymmetry to MDD and anhedonia, we explored the effect of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) stimulation on frontal and posterior EEG alpha asymmetry (FAA and PAA, respectively), in this exploratory investigation. 61 participants randomly received sham (n = 11), bilateral (BS; n = 25), or unilateral stimulation (US; n = 25) of the DLPFC. The Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) was administered. FAA and PAA were calculated by subtracting the natural log-transformed alpha power of the right (F8 or T6) from that of the left (F7 or T5) EEG channel. Furthermore, alpha peak was defined as the frequency where alpha power was at its maximum. BS and US both reduced anhedonia symptoms in the active compared to the sham group. Even non-responders in the BS group showed a decreased anhedonia. Interestingly in the BS group, only the patients who showed a right-lateralized FAA or PAA at baseline showed a reduction in anhedonia. However, in the US group, only patients with left-lateralized FAA or right-lateralized PAA showed a decrease in anhedonia. PAA at baseline predicted symptoms post treatment. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation between baseline alpha peak values and SHAPS scores post treatment were found in the BS group. PAA was a better predictor of anhedonia and reduction of depressive symptoms in both groups. BS may produce larger effects with regard to anhedonia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating mental illness with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 14.6% in high-income and 11.1% in low- to middle-income countries1 and is highly correlated with increased economic and social difficulties, as well as hospitalization2,3,4. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy have been shown to help reduce MDD symptoms, although up to 50% of patients may end up dealing with refractory symptoms. As a result, alternative approaches to treatment are necessary to improve therapeutic outcomes considering the evidence suggesting the low efficacy of antidepressants, especially in mild and moderate depression5.

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) have shown promising results in alleviating symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia6, obsessive compulsive disorder7, and MDD8,9,10,11 as well as in cognitive enhancements both in clinical samples and healthy individuals12,13,14,15. Although a considerable number of studies have investigated the therapeutic efficacy of rTMS in major depression, few have studied its effects on specific symptoms of MDD, such as anhedonia. Anhedonia is a transdiagnostic factor and one of the core diagnostic symptoms of MDD, but appears in other psychiatric disorders as well, such as schizophrenia16, eating disorders17,18, and substance abuse19, therefore it is not considered a symptom exclusive to MDD. Anhedonia has been found to be a predictor of poor psychosocial functioning20 and treatment outcomes after pharmacotherapy21,22, psychotherapy23, and rTMS treatment24. Anhedonia has essentially been defined as the loss of pleasure, inability to experience joy, or lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, being a result of disturbances in and/or dysfunctional interactions between stress and the reward system25,26.

Considering that there are no treatments specifically targeting anhedonia in MDD, several studies have aimed to find new treatment options in recent years among which some focused on the role of melatonin27 and glutamate28 showing a possible role of glutamate in anhedonia. There are reports that show blocking astrocytic glutamate absorption in the prefrontal cortex could lead to anhedonia29 and glutamate levels in the left basal ganglia are related to anhedonia and psychomotor retardation30. There is also evidence regarding the possible role of glutamate in the ventral tegmental area and the reward pathway31 which may be dysfunctional in patients suffering from anhedonia. Furthermore, Réus et al. showed that memantine, a prescription drug mainly used to treat dementia, could reduce anhedonia by balancing the corticosterone levels and increasing the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in prefrontal regions of the brain28.

There are reasons to believe that rTMS can produce desirable outcomes in patients suffering from anhedonia and MDD. First, significant correlations have been observed between psychomotor retardation and anhedonia in MDD patients32. Both symptoms may be linked to dysfunction of dopaminergic neural circuits and share similar neural correlates33. There are studies on the effects of rTMS on psychomotor retardation in patients with depression34,35,36. Thomas Oliver et al. applied rTMS over left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (LDLPFC) of seven MDD patients for 15 sessions and found out that rTMS had a positive effect on psychomotor retardation36. In another study by Baeken et al., (2010), rTMS improved psychomotor retardation in patients with MDD as well34.

Second, there is evidence indicating that rTMS can modulate glutamate levels in MDD patients37. Young et al. used a 10-Hz rTMS protocol over LDLPFC over 15 consecutive days, leading to modulation of glutamate levels, compared to baseline (11% increase) and the alleviation of MDD symptoms. Furthermore, significantly increased glutamate levels were observed in the stimulated region among responders to the treatment, compared to non-responders38. It has been shown in studies with healthy participants that applying high-frequency rTMS over LDLPFC could change glutamatergic neuron activations, however the changes in glutamate levels were not only limited to the stimulated area and increased glutamate levels could be traced in the right DLPFC (RDLPFC) and the left cingulate cortex as well. Changes in glutamate levels are also related to the baseline levels prior to stimulation because participants with lower glutamatergic concentration could experience higher levels of glutamate after rTMS sessions39.

According to neuroimaging studies, there are apparent dysfunctions in the reward pathway of patients with MDD, psychiatric, and neurodevelopmental disorders40. Regarding depressed patients, such dysfunctions are associated with symptoms such as anhedonia, reward-related perception, and memory deficits41. There is also good evidence for connections between ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a part of reward pathway, and DLPFC42,43, and evidence that RDLPFC rTMS could result in modulations in vmPFC activity42. Considering that MDD has been shown relate to dysfunction in the vmPFC/rACC44 which has neural connections with the striatum and could be considered part of the reward circuit45. Considering their role in anhedonia46, it can be inferred that activity in these regions are good candidates for further investigation in the context of anhedonia, MDD, and rTMS.

Based on the evidence regarding the relationship between frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) and posterior alpha asymmetry (PAA) with MDD47,48,49,50, the strong temporal stability for overall posterior alpha and PAA51, and especially the relationship between anhedonia and PAA previously reported52, the alpha asymmetry index in the frontal and posterior regions of the brain was considered the main focus of the current work. We investigate the sensitivity of this alpha symmetry index to anhedonia symptoms and response to treatment in MDD patients. Resting PAA has been reported to be heritable53, continues to persist even after remission54, and can predict response to antidepressant treatment52,55 thus making it an promising candidate for the current investigation. For example, resting FAA is believed to reflect approach-avoidance behaviors56, with relatively reduced left frontal activity indexing reduced motivation, anhedonia, and blunted reward sensitivity52,57.

High-frequency unilateral stimulation (HF-US), low-frequency unilateral stimulation (LF-US), sequential bilateral stimulation (BS) and theta burst stimulation (TBS) are the main rTMS protocols that have been used in the context of depression58,59, among which LF-US and sequential BS, despite promising results, have been relatively less investigated. In a recent meta-analysis, LF-US was reported to produce a 40.9% treatment response and 16.4% remission rate, and HF-US a 44.6% treatment response and 21.9% remission rate, with no significant difference between the two protocols8. BS has also been shown to have similar efficacy to HF-US60 and LF-US61. Treatment response produced by the sequential BS has been reported at 64.3% and the HF-US at 68.6%, with remission rates of 33.9% and 37.3%, respectively, and no significant difference between the two60. Another study comparing the effects of LF-US with sequential BS showed no significant difference in their efficacy61.Although there is still no conclusive evidence regarding superiority/inferiority as well as the behavioral and electrophysiological effects of bilateral versus unilateral rTMS in the context of MDD, bilateral rTMS is considered a promising protocol, comparable with standard antidepressants and unilateral rTMS62. Based on neuroimaging evidence, the hypothesis of the dysregulation of cortical functioning in depressed individuals, with lower and higher activity in the left and the right DLPFC, respectively63, gained more support, therefore, suggesting the therapeutic potential of a bilateral stimulation protocol that ideally aimed to correct for this imbalance by targeting the left and right DLPFC via the excitatory and inhibitory rTMS protocols, respectively62,64,65. Considering their comparable clinical efficacy in the context of depression, it would thus be very curious to investigate the potential therapeutic benefits of a bilateral stimulation protocol considering specific symptoms, such as anhedonia.

Although there is still no straightforward answer regarding the direction of the alpha asymmetry index (left- vs. right-lateralized), in either the frontal or posterior regions, based on the evidence regarding a left-lateralized alpha pattern in the prefrontal areas in patients suffering from MDD66, differences between responders and non-responders to treatment were studied in terms of FAA, in specific expecting a change in the degree and/or the direction of the lateralization as a result of the intervention. Similarly, and based on the evidence suggesting a relationship between right-lateralized alpha pattern in posterior regions and anhedonia52, the sensitivity of this index was considered both in the context of response to treatment and its relationship with anhedonia both at baseline and after the treatment.

Methods

Considering that this paper presents another portion of the same data that has been collected along with that of a previous study67, the sections regarding participants, design, and data collection are identical, however they will be rephrased here again. It is worth mentioning that this second part of the original study (Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT03468686) has been registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) directory after the data collection, however, before the analysis of the data regarding the effect of the intervention on anhedonia symptoms68.

Participants

61 MDD patients volunteered to participate in this study who were then randomly assigned to one of three independent groups, namely sham (n = 11, 5 female, 10 sessions), unilateral (n = 25, 16 female, 20 sessions), and bilateral (n = 25, 15 female, 20 sessions). The inclusion criteria were: being between 18 to 70 years old, having an MDD diagnosis based on the DSM-V criteria, agreeing to sign the informed consent form, and having score of 20 or higher (the recommended cutoff for “moderate” depression being > 1769 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). Having already received rTMS treatment, use of a pacemaker, heightened risk of seizures due to comorbid neurological conditions, presence of metal objects in the neck or head, history of seizures in first-degree relatives, history of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and/or being pregnant or breast-feeding were considered exclusion criteria. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran. We performed all experiments in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation and written informed consent was obtained all participants. The demographic and clinical information of the included patients are presented in Table 1. A minimum reduction of 50% in HAM-D scores were defined as the criterion for responding to treatment. Two participants from the sham group and one from the unilateral group were excluded due to problems with their clinical/EEG data.

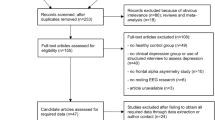

Design

Patients were randomly assigned to independent experimental and control groups in a double-blind between-participants manner. Eyes-closed electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded in an acoustically and electromagnetically shielded room after clinical assessments including BDI-II, HAM-D, and Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) questionnaires, before and after the rTMS treatment course. A minimum of 50% decrease in HAM-D scores was considered as treatment response, in accordance with standard practice70. The experimental design is depicted in Fig. 1.

Clinical assessments

Depression

The HAM-D71 was considered as the primary outcome measure due to its widespread clinical and research use and acceptable levels of internal consistency, inter-rater, and test–retest reliability72.

Anhedonia

The Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS)73 is a self-report 14-item instrument that is used to measure hedonic capacity. Each of the items could be responded by choosing to Definitely Agree, Agree, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree with the content of the item. A higher total SHAPS score indicated higher levels of anhedonia. SHAPS is a widely used questionnaire and has demonstrated reliability and validity for the assessment of hedonic capacity in adult outpatients with MDD74.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

A Neuro-MS stimulator (Neurosoft, Russia) with a figure-eight coil was used to administer the rTMS. The visual method of determining resting motor threshold (RMT) was used in the current study, considering its relative reliability, ease of use, faster application75, and common use in experimental76,77,78,79 and clinical research80,81,82. The lowest intensity that caused a visible contraction of the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle in five out of ten single TMS pulses was considered as the RMT83. In the unilateral group, the left DLPFC was located based on the 10–20 international system. The unilateral stimulation (US) protocol consisted of 10 pulses per second (10 Hz), 75 trains with a train duration of 5 s and 10 s of delay between trains (inter-train interval; ITI), which resulted in a total of 3750 pulses per session. Stimulation intensity was set at 100% of each participant’s RMT84,85. In the bilateral stimulation (BS) group, the right DLPFC was stimulated in addition to the left DLPFC. The inhibitory protocol, i.e., one pulse per second (1 Hz) was delivered in 150 trains each with a duration of 10 s and an ITI of 2 s. The stimulation intensity was at 120% of each participant’s RMT and altogether 1500 pulses were administered to the right DLPFC62 in addition to the stimulation of the left DLPFC which was identical to the one used in the US group. The sham group received the same protocol as the US group, except that the coil was placed on the head on a single wing with a 90° angle thus perpendicular to the scalp84.

EEG recording

A Mitsar amplifier (Mitsar., St. Petersburg, Russia) and a 19 channel ElectroCap (ElectroCap, Inc., OH) was used for EEG recording. The sampling rate, high pass filter, and low pass filter were set at 500 Hz, 0.3 Hz, and 50 Hz, respectively. Reference electrodes were A1 + A2. Impedances of all electrodes were kept below 5 KΩ during the recording.

EEG analysis

Asymmetry indices

Continuous EEG data was segmented into non-overlapping 4-s epochs to address the nonstationary problem of EEG signals86,87. Absolute power was calculated using fast Fourier transform (FFT) in the alpha (8–13 Hz) frequency band for each epoch and channel88. A specific power was then determined for each individual by calculating the mean power across all epochs for each channel. Finally, FAA was computed by subtracting the natural log-transformed alpha power of the right (F8) from that of the left (F7) EEG channel (FAA = ln(F8) − ln(F7)). PAA was similarly calculated utilizing spectral power in the alpha range for T6 and T5 (PAA = ln(T6) − ln(T5)). This method yields a unidimensional scale that reflects the relative activity levels of the right and left hemispheres. The midpoint of the scale corresponds to zero or symmetrical activity. So, higher values signify a comparatively greater degree of right-lateralized alpha power, while negative scores denote a relatively higher level of left-lateralized power56. Moreover, the log-difference score offers a certain level of correction for the overall alpha power56,89 and addresses factors such as individual variations in skull thickness, which can impact signal amplitude89,90,91.

Alpha peak frequency

Based on the study of Bailey et al.92 and findings of Arns et al.,93, individualized Alpha Peak Frequency was computed by averaging across F3, Fz and F4 electrodes, in order to look at its correlation with the state of anhedonia before and after the intervention.

Statistical analysis

To detect the changes from pre to post intervention in the behavioral and EEG measures and compare them among the independent groups, a mixed ANOVA test was used in which the independent variables were: Time (pre and post), defined as the within-participant and Group as the between-participant variable. Group was defined either based on the stimulation type (Sham, Unilateral, or Bilateral) or a specific criterion such as response to treatment (e.g., Responders and Non-responders). In this model, changes from pre to post in one group were compared and contrasted with those of another. Different tests using this model was performed considering the behavioral SHAPS score, i.e., anhedonia and FAA or PAA as the dependent variable. Furthermore, a linear regression with the Enter method was performed to examine the predictive potential of the FAA and PAA, with anhedonia scores after the treatment as the dependent variable. SPSS was used for statistical analysis. Significance level was considered 0.05 for all the comparisons and effect sizes are reported both as the original eta squared produced in SPSS and then converted to Cohen’s d using the https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html online tool94.

Results

Behavioral results

Anhedonia and bilateral stimulation

A significant Time × Group interaction in SHAPS scores (F(1,32) = 11.02, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.256, converted d = 1.17) was found with a decreasing trend in the active group meaning that bilateral active stimulation resulted in a significant decrease in anhedonia symptoms. Non-responders to this arm of treatment benefited from the active BS compared to their sham counterparts with regard to their anhedonia symptoms, based on a significant Time × Group interaction (F(1,11) = 5.934, p = 0.033, η2 = 0.350, converted d = 1.46). Moreover, if patients were divided into two groups, based on their frontal or posterior lateralization at baseline (i.e., a right lateralized or left lateralized alpha), the effect of active vs. sham stimulation was significantly affected, meaning that patients with right, but not left-lateralized FAA at baseline, who received active BS experience significantly decreased anhedonia symptoms compared to their sham counterparts ((F(1,20) = 7.080, p = 0.015, η2 = 0.261, converted d = 1.18). In addition, the same pattern was found in patients with right, but not left-lateralized PAA ((F(1,18) = 9.147, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.337, converted d = 1.42). The values of SHAPS categorized based on the lateralization of the FAA and PAA for all stimulation groups are presented in Table 2.

Anhedonia and unilateral stimulation

A significant Time × Group interaction in SHAPS scores (F(1,31) = 9.78, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.240, converted d = 1.12) with a decreasing trend in the active group was found, meaning that unilateral active stimulation resulted in a significant decrease in anhedonia symptoms. Non-responders to treatment did not benefit from US in terms of reductions in anhedonia symptoms. It is worth mentioning that the BS produced a larger effect size (0.256 vs. 0.240) for the reduction in anhedonia symptoms. Moreover, if patients were divided into two groups, based on their frontal or posterior lateralization at baseline (Table 2), the effect of active vs. sham stimulation is significantly affected. Meaning that patients with left- but not right-lateralized FAA at baseline who received active US, experienced decreased anhedonia symptoms compared to their sham counterparts (F(1,11) = 5.759, p = 0.035, η2 = 0.344, converted d = 1.44). However, the opposite pattern was found when PAA was considered, meaning that patients with right, but not left-lateralized PAA benefited from the US in terms of reductions in anhedonia symptoms (F(1,20) = 6.782, p = 0.017, η2 = 0.253, converted d = 1.16).

Unilateral vs. bilateral in anhedonia

No significant differences were observed when comparing BS and US regarding changes in anhedonia.

EEG results

Asymmetry results (FAA and PAA)

It is noteworthy that none of the asymmetry indices significantly differed among the three groups of bilateral, sham, and unilateral at baseline. The non-significant trends from pre to post intervention in BS and US groups are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Bilateral group

Comparing active vs. sham in FAA and PAA

The mixed ANOVA results showed significant Time × Group interactions considering FAA values as the dependent variable (F(1,32) = 6.11, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.16, converted d = 0.87) in a BS vs. sham comparison. However, the effect of the BS alone (pre vs. post) was not significant meaning that it was the changes from pre to post in the sham group that was causing the results to reach significance. It is noteworthy that the average FAA was right lateralized (positive) at baseline in both groups, however it became left lateralized in the sham group (t(8) = 3.352, p = 0.010) when comparing pre and post intervention (1 month time window).

Comparing responders vs. non-responders in FAA and PAA

There was a significant Time × Group interaction considering PAA values as the dependent variable (F(1,23) = 5.25, p = 0.031, \(\eta\)2 = 0.186, converted d = 0.956) with an increasing trend in BS responders (n = 21), i.e., becoming more right-lateralized vs decreasing in BS non-responders i.e., becoming left-lateralized. This means that the BS had differential effects on individuals that eventually ended up responding to the treatment and the ones that did not (Fig. 3). The average PAA was left-lateralized at baseline, however became right-lateralized after the intervention, in BS responders (t(20) = − 2.242, p = 0.036). The exact opposite pattern, however non-significant, was seen in BS non-responders.

Scatter plots representing the significant correlations between baseline (a) Posterior Alpha Asymmetry (PAA_Pre) and Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) in the unilateral group (p = 0.015), (b) PAA_Pre and SHAPS_Post in the unilateral group (p = 0.008), and (c) PAA_Pre and SHAPS_Post in the bilateral group (p = 0.020).

Correlations

The correlations among alpha asymmetry indexes and SHAPS scores in the bilateral group can be found in Table 3 and the scatter plots of the significant ones can be found in Fig. 3. As can be seen, a significant correlation exists between anhedonia scores after the treatment and values of PAA at baseline.

Unilateral

No significant differences were found in asymmetry values neither when comparing the active and sham groups nor when comparing US responders (n = 19) and non-responders.

Correlations

Significant correlations between PAA at baseline and anhedonia scores are found. The correlations among alpha asymmetry indexes and SHAPS scores in the unilateral group can be found in Table 3.

Unilateral vs. bilateral

Whole sample FAA and PAA

A marginally significant Time × Group interactions was found when considering PAA values as the dependent variable (F(1,47) = 3.91, p = 0.054) with an increasing trend in the BS group, i.e., becoming more right-lateralized and a decreasing trend in the US group, i.e., becoming left-lateralized.

Responders and FAA and PAA

Significant Time × Group interactions when PAA was considered as the dependent variable (F(1,38) = 5.2, p = 0.017, η2 = 140, converted d = 0.806) was found when comparing BS and US responders. The average PAA in the responders of the bilateral group at baseline was negative, meaning that patients later responding to the treatment showed a left-lateralized PAA. This group of patients show, on average, a positive PAA after treatment, i.e., a right lateralized PAA (significant, p = 0.036). The responders in the unilateral group, however, show exactly the opposite trend (non-significant), i.e., showing a right-lateralized PAA at baseline, which becomes left-lateralized post intervention that can be seen in Fig. 4. No significant effects were observed when comparing the non-responders of the two groups.

Alpha peak

The correlations among alpha asymmetry indexes and SHAPS scores in the bilateral, unilateral, and sham groups can be found in Table 4. In addition, the correlation between alpha peak and SHAPS scores at baseline is presented in Table 5 when participants of all groups are combined.

Linear regression results

Considering post-intervention SHAPS scores as the dependent variable, the following is the results of the linear regression analysis using Enter method in each group, to examine the predictive value of the frontal and posterior alpha asymmetry, focusing on anhedonia. It is worth mentioning that the baseline values of alpha asymmetry in the frontal or posterior regions showed to significance in predicting the response to treatment in terms of reduction in depressive symptoms.

Bilateral

Baseline PAA was significantly predicted variations in SHAPS scores post intervention (\({R}^{2}\)=0.215, F(1,23) = 6.285, p = 0.02, β = − 1.693).

Unilateral

Baseline PAA significantly predicted variations in SHAPS scores post intervention (\({R}^{2}\)=0.279, F(1,22) = 8.515, p = 0.008, β = 1.992).

Discussion

BS and US both reduced anhedonic symptoms compared to the sham group. In addition to responders in both groups, even non-responders in the BS group showed a decrease in anhedonia symptoms. It is worth noting that in the BS group, only patients who showed a right-lateralized alpha asymmetry in the frontal or parietal regions at baseline showed a reduction in anhedonia symptoms. On the other hand, in the US group, only patients with left-lateralized FAA or right-lateralized PAA showed a decrease in symptoms of anhedonia. In the BS group, responders showed a significant increased right-lateralized PAA compared to non-responders. There were no significant differences in the US group, neither in FAA values nor PAA between responders and non-responders.

Anhedonia symptoms

In our study, rTMS reduced anhedonia in MDD patients in both groups which is in line with previous studies95,96,97. Studies that investigated the effects of rTMS on anhedonia have targeted diverse areas such as the DLPFC24,98, rostromedial PFC99, and LDLPFC95,96,97,100, however all either reported amelioration of anhedonia symptoms or changes in the activity in the reward pathway. Considering that targeting the dorsomedial and rostromedial areas with the figure-8 coil is not feasible, and that the use of double cone coils is not yet common in clinical settings, plus the findings showing that dorsomedial stimulation may only lead to a reduction in anhedonia but not depressive symptoms98, it seems that DLPFC stimulation is still an optimal candidate in the context of anhedonia and depressive symptoms.

So far, the efficacy of BS in comparison with US to reduce depressive symptoms in MDD patients has been investigated in several meta-analyses and retrospective studies60,62,65,101,102, with all studies reporting no superiority of the bilateral over unilateral rTMS and consistent with previous studies, a recent retrospective study with a large sample size10 showed no superiority for BS over US60.

In our study, although, in line with previous works, no superiority of the bilateral protocol over the unilateral protocol was observed. However, in the BS group, not only responders to treatment, but also the non-responders showed a decrease in anhedonia symptoms. It seems that BS can, at least for some types of depression and some depressive symptoms (e.g., rumination and anhedonia) produce more favorable outcomes compared to the standard unilateral protocol. For example, according to the type of depression, BS has been shown to be superior to US in reducing the symptoms of depression in the elderly103.

Electrophysiological correlates of anhedonia

Patients with right-lateralized FAA at baseline, who received BS and patients with left-lateralized FAA at baseline who received US showed decreased anhedonia symptoms compared to their sham counterparts. FAA is considered one of the markers of reward processing in depression and has been investigated in different studies104,105,106, reported to be associated with withdrawal behavior and reduced motivation107,108. Studies have shown that there is a relationship between FAA and anhedonia66,109 and that higher alpha power in the right frontal lobe is associated with lower regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) values in the frontal and striatum of the right hemisphere, both involved in the processing of reward behavior66.

Furthermore, a correlation between anhedonia and posterior asymmetry was found. It is worth noting that more areas in the right hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere have been shown to be related to anhedonia in depressed patients109. The baseline right-lateralized alpha asymmetry in our patients may indicate the malfunctioning of the reward pathway. In previous studies, it has been shown that the dysfunction of the reward pathway at baseline could be predictive of the response to treatment24. Our results showed that PAA at baseline can predict the level of anhedonia symptoms post-treatment and changes in PAA values, as a potential neuromarker of treatment response, was observed in responders of the BS group. In addition to FAA, alpha asymmetry in the posterior regions has also been proposed as a neuromarker for MDD. In our study, PAA could predict the level of anhedonia symptoms in depressed patients in both bilateral and US groups. Increased PAA was shown to be associated with anhedonia and rumination52. Evidence shows that patients with melancholic depression exhibit more left-lateralized PAA with the opposite pattern in non-melancholic depressed people110. Abnormal PAA may indicate a malfunction of the reward pathway and the presence of anhedonia symptoms, thus making it a potentially informative biomarker of anhedonia. In the BS group and considering PAA, becoming more left-lateralized was associated with a lack of response to treatment. PAA has been introduced in previous studies as one of the biomarkers of response to antidepressants111,112. In these studies, treatment responders were more likely to exhibit left-lateralization of PAA. This suggests that PAA may indicate the status of the reward pathway in depressed patients and can be considered an EEG marker predicting the response to rTMS treatment and the reduction of anhedonia symptoms.

Limitations

The results of the current exploratory study should be interpreted cautiously due to the limitations including but not limited to: low number of patients in each treatment arm and especially the sham group, lower number of rTMS sessions (n = 10) in the sham group compared to the active stimulation groups, low number of patients after dividing them into responders vs. non-responders thus affecting the reliability of the comparisons between these subgroups, and finally the lack of precise and personalized neuronavigated target engagement.

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to compare the effects of bilateral and unilateral rTMS on anhedonia and its electrophysiological correlates and explore the sensitivity and relevance of the alpha asymmetry index in the frontal and posterior regions of the brain as a marker of treatment response in general and anhedonia in specific. rTMS reduced anhedonia symptoms and MDD symptoms in both groups. PAA at baseline could predict the anhedonia symptoms post treatment. Despite the emphasis of previous studies on FAA, PAA was a better predictor of anhedonia and reduction of depressive symptoms in both groups. Among the classic rTMS protocols, bilateral DLPFC stimulation, although thus far not shown to be superior for the reduction of MDD symptoms, appears to produce larger effects with regard to the reduction of symptoms of anhedonia.

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript. The datasets analyzed here are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bromet, E. et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 9(1), 1–16 (2011).

Fröjd, S. A. et al. Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. J. Adolesc. 31(4), 485–498 (2008).

McFarland, B. R. & Klein, D. N. Mental health service use by patients with dysthymic disorder: treatment use and dropout in a 7 1/2-year naturalistic follow-up study. Compr. Psychiatry 46(4), 246–253 (2005).

Sobocki, P., Ekman, M., Ågren, H., Runeson, B. & Jönsson, B. The mission is remission: health economic consequences of achieving full remission with antidepressant treatment for depression. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 60(7), 791–798 (2006).

Fournier, J. C. et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 303(1), 47–53 (2010).

Aleman, A., Enriquez-Geppert, S., Knegtering, H. & Dlabac-de Lange, J. J. Moderate effects of noninvasive brain stimulation of the frontal cortex for improving negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis of controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 89, 111–118 (2018).

Rehn, S., Eslick, G. D. & Brakoulias, V. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of different cortical targets used in repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Psychiatr. Q. 89, 645–665 (2018).

Cao, X., Deng, C., Su, X. & Guo, Y. Response and remission rates following high-frequency vs. low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) over right DLPFC for treating major depressive disorder (MDD): a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind trials. Front. Psychiatry. 9, 413 (2018).

Rachid, F. Maintenance repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for relapse prevention in with depression: A review. Psychiatry Res. 262, 363–372 (2018).

Shen, X. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J. Affect. Disord. 211, 65–74 (2017).

Vida, R. G. et al. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder (MDD) after two antidepressant treatment failures: meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 23(1), 545 (2023).

Beynel, L. et al. Effects of online repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on cognitive processing: a meta-analysis and recommendations for future studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 47–58 (2019).

Kazemi, R. et al. Alpha frequency rTMS modulates theta lagged nonlinear connectivity in dorsal attention network. Brain Res. Bull. 162, 271–281 (2020).

Martin, D. M., McClintock, S. M., Forster, J. J., Lo, T. Y. & Loo, C. K. Cognitive enhancing effects of rTMS administered to the prefrontal cortex in patients with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual task effects. Depress. Anxiety. 34(11), 1029–1039 (2017).

Patel, R., Silla, F., Pierce, S., Theule, J. & Girard, T. A. Cognitive functioning before and after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): a quantitative meta-analysis in healthy adults. Neuropsychologia. 141, 107395 (2020).

Gard, D. E., Kring, A. M., Gard, M. G., Horan, W. P. & Green, M. F. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophrenia Res. 93(1–3), 253–260 (2007).

Davis, C. & Woodside, D. B. Sensitivity to the rewarding effects of food and exercise in the eating disorders. Compr. Psychiatry. 43(3), 189–194 (2002).

Tchanturia, K. et al. Altered social hedonic processing in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45(8), 962–969 (2012).

Hatzigiakoumis, D. S., Martinotti, G., Giannantonio, M. D. & Janiri, L. Anhedonia and substance dependence: clinical correlates and treatment options. Front. Psychiatry. 2, 10 (2011).

Vinckier, F., Gourion, D. & Mouchabac, S. Anhedonia predicts poor psychosocial functioning: results from a large cohort of patients treated for major depressive disorder by general practitioners. Eur. Psychiatry. 44, 1–8 (2017).

McMakin, D. L. et al. Anhedonia predicts poorer recovery among youth with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment–resistant depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 51(4), 404–411 (2012).

Uher, R. et al. Depression symptom dimensions as predictors of antidepressant treatment outcome: replicable evidence for interest-activity symptoms. Psychol. Med. 42(5), 967–980 (2012).

Carl, H. et al. Sustained anterior cingulate cortex activation during reward processing predicts response to psychotherapy in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 203, 204–212 (2016).

Downar, J. et al. Anhedonia and reward-circuit connectivity distinguish nonresponders from responders to dorsomedial prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 76(3), 176–185 (2014).

Pizzagalli, D. A. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 393–423 (2014).

Rizvi, S. J., Pizzagalli, D. A., Sproule, B. A. & Kennedy, S. H. Assessing anhedonia in depression: Potentials and pitfalls. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 65, 21–35 (2016).

Martinotti, G. et al. Agomelatine versus venlafaxine XR in the treatment of anhedonia in major depressive disorder: a pilot study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 32(4), 487–491 (2012).

Réus, G. Z. et al. Memantine treatment reverses anhedonia, normalizes corticosterone levels and increases BDNF levels in the prefrontal cortex induced by chronic mild stress in rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 27, 175–182 (2012).

John, C. S. et al. Blockade of astrocytic glutamate uptake in the prefrontal cortex induces anhedonia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 37(11), 2467–2475 (2012).

Haroon, E. et al. Conceptual convergence: increased inflammation is associated with increased basal ganglia glutamate in patients with major depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 21(10), 1351–1357 (2016).

Shabat-Simon, M., Levy, D., Amir, A., Rehavi, M. & Zangen, A. Dissociation between rewarding and psychomotor effects of opiates: differential roles for glutamate receptors within anterior and posterior portions of the ventral tegmental area. J. Neurosci. 28(34), 8406–8416 (2008).

Lemke, M., Puhl, P., Koethe, N. & Winkler, T. Psychomotor retardation and anhedonia in depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 99(4), 252–256 (1999).

Stein, D. J. Depression, anhedonia, and psychomotor symptoms: the role of dopaminergic neurocircuitry. CNS Spectrums. 13(7), 561–565 (2008).

Baeken, C. et al. HF-rTMS treatment decreases psychomotor retardation in medication-resistant melancholic depression. Progr. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 34(4), 684–687 (2010).

Hoeppner, J. et al. Influence of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on psychomotor symptoms in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 260, 197–202 (2010).

Thomas-Ollivier, V. et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on psychomotor retardation in major depression: a pilot feasibility study. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 28(1), 62–65 (2016).

Pradhan, S., Kirton, A., MacQueen, G., MacMaster, F., editors. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on dorsolateral prefrontal glutamate in youth with treatment-resistant depression. In BMC Proceedings (Springer, 2015).

Young, C. et al. Anhedonia and general distress show dissociable ventromedial prefrontal cortex connectivity in major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 6(5), e810-e (2016).

Michael, N. et al. Metabolic changes after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the left prefrontal cortex: a sham-controlled proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) study of healthy brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17(11), 2462–2468 (2003).

Dichter, G. S., Damiano, C. A. & Allen, J. A. Reward circuitry dysfunction in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and genetic syndromes: animal models and clinical findings. J. Neurodev. Disord. 4(1), 1–43 (2012).

Russo, S. J. & Nestler, E. J. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14(9), 609–625 (2013).

Baumgartner, T., Knoch, D., Hotz, P., Eisenegger, C. & Fehr, E. Dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex orchestrate normative choice. Nat. Neurosci. 14(11), 1468–1474 (2011).

Saraiva, A. C. & Marshall, L. Dorsolateral–ventromedial prefrontal cortex interactions during value-guided choice: a function of context or difficulty?. J. Neurosci. 35(13), 5087–5088 (2015).

Drevets, W. C. et al. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 386(6627), 824–827 (1997).

Vassena, E., Krebs, R. M., Silvetti, M., Fias, W. & Verguts, T. Dissociating contributions of ACC and vmPFC in reward prediction, outcome, and choice. Neuropsychologia. 59, 112–123 (2014).

Keedwell, P. A., Andrew, C., Williams, S. C., Brammer, M. J. & Phillips, M. L. The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 58(11), 843–853 (2005).

Allen, J. J., Urry, H. L., Hitt, S. K. & Coan, J. A. The stability of resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression. Psychophysiology. 41(2), 269–280 (2004).

Blackhart, G. C., Minnix, J. A. & Kline, J. P. Can EEG asymmetry patterns predict future development of anxiety and depression?: A preliminary study. Biol. Psychol. 72(1), 46–50 (2006).

Thibodeau, R., Jorgensen, R. S. & Kim, S. Depression, anxiety, and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: a meta-analytic review. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 115(4), 715 (2006).

Van Der Vinne, N., Vollebregt, M. A., Van Putten, M. J. & Arns, M. Frontal alpha asymmetry as a diagnostic marker in depression: Fact or fiction? A meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin. 16, 79–87 (2017).

Tenke, C. E. et al. Temporal stability of posterior EEG alpha over twelve years. Clin. Neurophysiol. 129(7), 1410–1417 (2018).

Umemoto, A. et al. Resting posterior alpha power and adolescent major depressive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 141, 233–240 (2021).

Bruder, G. E., Tenke, C. E., Warner, V. & Weissman, M. M. Grandchildren at high and low risk for depression differ in EEG measures of regional brain asymmetry. Biol. Psychiatry. 62(11), 1317–1323 (2007).

Henriques, J. B. & Davidson, R. J. Regional brain electrical asymmetries discriminate between previously depressed and healthy control subjects. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 99(1), 22 (1990).

Bruder, G.E., Tenke, C.E., Kayser, J. Electrophysiological predictors of clinical response to antidepressants. In The Clinical Handbook for the Management of Mood Disorders380–393 (2013).

Coan, J. A. & Allen, J. J. Frontal EEG asymmetry as a moderator and mediator of emotion. Biol. Psychol. 67(1–2), 7–50 (2004).

Nusslock, R. et al. Comorbid anxiety moderates the relationship between depression history and prefrontal EEG asymmetry. Psychophysiology. 55(1), e12953 (2018).

Blumberger, D. M. et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 391(10131), 1683–1692 (2018).

Cohen, S. L., Bikson, M., Badran, B. W. & George, M. S. A visual and narrative timeline of US FDA milestones for Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) devices. Brain Stimul. 15(1), 73 (2021).

Aaronson, S. T. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes with left unilateral and sequential bilateral Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) treatment of major depressive disorder in a large patient registry. Brain Stimul. 15(2), 326–336 (2022).

Galletly, C. A., Carnell, B. L., Clarke, P. & Gill, S. A comparison of right unilateral and sequential bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a naturalistic clinical Australian study. J. ECT. 33(1), 58–62 (2017).

Berlim, M. T., Van den Eynde, F. & Daskalakis, Z. J. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy and acceptability of bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treating major depression. Psychol. Med. 43(11), 2245–2254 (2013).

Fitzgerald, P. B., Laird, A. R., Maller, J. & Daskalakis, Z. J. A meta-analytic study of changes in brain activation in depression. Hum. Brain Map. 29(6), 683–695 (2008).

Bajbouj, M. et al. Evidence for impaired cortical inhibition in patients with unipolar major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 59(5), 395–400 (2006).

Chen, J. J. et al. Bilateral vs. unilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treating major depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 219(1), 51–57 (2014).

Cantisani, A. et al. EEG marker of inhibitory brain activity correlates with resting-state cerebral blood flow in the reward system in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 266, 755–764 (2016).

Kazemi, R. et al. Electrophysiological and behavioral effects of unilateral and bilateral rTMS; A randomized clinical trial on rumination and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 317, 360–372 (2022).

Hadipour, A. L., Coetzee, J., Kazemi, R. Effectiveness of unilateral and bilateral DLPFC rTMS on anhedonia in patients with major depressive disorder. (2023).

Zimmerman, M., Martinez, J. H., Young, D., Chelminski, I. & Dalrymple, K. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J. Affect. Disord. 150(2), 384–388 (2013).

Riedel, M. et al. Response and remission criteria in major depression–a validation of current practice. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44(15), 1063–1068 (2010).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 23(1), 56 (1960).

Trajković, G. et al. Reliability of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a meta-analysis over a period of 49 years. Psychiatry Res. 189(1), 1–9 (2011).

Snaith, R. P. et al. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 167(1), 99–103 (1995).

Nakonezny, P. A., Carmody, T. J., Morris, D. W., Kurian, B. T. & Trivedi, M. H. Psychometric evaluation of the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) in adult outpatients with major depressive disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 25(6), 328 (2010).

Pridmore, S., Fernandes Filho, J. A., Nahas, Z., Liberatos, C., George, M. S. Motor Threshold in Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Comparison of a Neurophysiological Method and a Visualization of Movement Method 25–27 (LWW, 1998).

Chick, C. F., Rolle, C., Trivedi, H. M., Monuszko, K. & Etkin, A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation demonstrates a role for the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in emotion perception. Psychiatry Res. 284, 112515 (2020).

Göbel, S. M., Calabria, M., Farne, A. & Rossetti, Y. Parietal rTMS distorts the mental number line: simulating ‘spatial’neglect in healthy subjects. Neuropsychologia. 44(6), 860–868 (2006).

Miller, J. G., Xia, G. & Hastings, P. D. Right temporoparietal junction involvement in autonomic responses to the suffering of others: A preliminary transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 7 (2020).

Oliveri, M. & Vallar, G. Parietal versus temporal lobe components in spatial cognition: Setting the mid-point of a horizontal line. J. Neuropsychol. 3(2), 201–211 (2009).

Chen, L., Hudaib, A. R., Hoy, K. E. & Fitzgerald, P. B. Is rTMS effective for anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder? An efficacy analysis comparing left-sided high-frequency, right-sided low-frequency, and sequential bilateral rTMS protocols. Depress. Anxiety. 36(8), 723–731 (2019).

Clarke, E. et al. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression with comorbid anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 252, 435–439 (2019).

Fitzgerald, P. B. et al. A randomized trial of rTMS targeted with MRI based neuro-navigation in treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 34(5), 1255–1262 (2009).

Rossini, P. M. et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 91(2), 79–92 (1994).

Blumberger, D. M. et al. A randomized double-blind sham-controlled comparison of unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 13(6), 423–435 (2012).

Fitzgerald, P. B. et al. A randomized, controlled trial of sequential bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 163(1), 88–94 (2006).

Zandbagleh, A., Azami, H., Mirzakuchaki, S., Daliri, M. R., Sanei, S., Premkumar, P. Multiscale fluctuation dispersion entropy of EEG as a physiological biomarker of schizotypy. IEEE Access. (2023).

Zandbagleh, A. et al. Graph-based analysis of EEG for schizotypy classification applying flicker Ganzfeld stimulation. Schizophrenia. 9(1), 64 (2023).

Varastegan, S. et al. Remember NIBS? tACS improves memory performance in elders with subjective memory complaints. GeroScience. 45(2), 851–869 (2023).

Smith, E. E., Reznik, S. J., Stewart, J. L. & Allen, J. J. Assessing and conceptualizing frontal EEG asymmetry: An updated primer on recording, processing, analyzing, and interpreting frontal alpha asymmetry. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 111, 98–114 (2017).

Eshel, Y., Witman, S., Rosenfeld, M. & Abboud, S. Correlation between skull thickness asymmetry and scalp potential estimated by a numerical model of the head. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 42(3), 242–249 (1995).

Leissner, P., Lindholm, L.-E. & Petersen, I. Alpha amplitude dependence on skull thickness as measured by ultrasound technique. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 29(4), 392–399 (1970).

Bailey, N. et al. Differentiating responders and non-responders to rTMS treatment for depression after one week using resting EEG connectivity measures. J. Affect. Disord. 242, 68–79 (2019).

Arns, M., Drinkenburg, W. H., Fitzgerald, P. B. & Kenemans, J. L. Neurophysiological predictors of non-response to rTMS in depression. Brain Stimul. 5(4), 569–576 (2012).

Lenhard, W., Lenhard, A. Computation of effect sizes. Psychometrica. 10.13140. RG. https://www.psychometrica.de/effectsize.html (2016).

Fukuda, A. M. et al. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on anhedonia in treatment resistant major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 11(9), e2329 (2021).

Pettorruso, M., di Giannantonio, M., De Risio, L., Martinotti, G. & Koob, G. F. A light in the darkness: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to treat the hedonic dysregulation of addiction. J. Addict. Med. 14(4), 272 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of connectivity-directed transcranial magnetic stimulation on anticipatory anhedonia. Depress. Anxiety. 38(9), 972–984 (2021).

Bodén, R., Bengtsson, J., Thörnblom, E., Struckmann, W. & Persson, J. Dorsomedial prefrontal theta burst stimulation to treat anhedonia, avolition, and blunted affect in schizophrenia or depression–a randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 290, 308–315 (2021).

Ryan, J., Pouliot, J. J., Hajcak, G. & Nee, D. E. Manipulating reward sensitivity using reward circuit–targeted transcranial magnetic stimulation. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 7(8), 833–840 (2022).

Duprat, R., Wu, G.-R., De Raedt, R. & Baeken, C. Accelerated iTBS treatment in depressed patients differentially modulates reward system activity based on anhedonia. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 19(7), 497–508 (2018).

Fitzgerald, P. B. et al. Equivalent beneficial effects of unilateral and bilateral prefrontal cortex transcranial magnetic stimulation in a large randomized trial in treatment-resistant major depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16(9), 1975–1984 (2013).

Sehatzadeh, S. et al. Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials over 2 decades. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 44(3), 151–163 (2019).

Trevizol, A. P. et al. Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant late-life depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 34(6), 822–827 (2019).

Kaiser, A. K., Gnjezda, M.-T., Knasmüller, S., Aichhorn, W. Electroencephalogram alpha asymmetry in patients with depressive disorders: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 1493–504 (2018).

Segrave, R. A. et al. Individualized alpha activity and frontal asymmetry in major depression. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 42(1), 45–52 (2011).

Stewart, J. L., Coan, J. A., Towers, D. N. & Allen, J. J. Resting and task-elicited prefrontal EEG alpha asymmetry in depression: Support for the capability model. Psychophysiology. 51(5), 446–455 (2014).

Briesemeister, B. B., Tamm, S., Heine, A. & Jacobs, A. M. Approach the good, withdraw from the bad—a review on frontal alpha asymmetry measures in applied psychological research. Psychology. 4(03), 261 (2013).

Harmon-Jones, E. & Gable, P. A. On the role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in approach and withdrawal motivation: An updated review of the evidence. Psychophysiology. 55(1), e12879 (2018).

Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., Arnold, W. M., Shadli, S. M., Jesulola, E., Agnew, L. L. Network analysis of frontal lobe alpha asymmetry confirms the neurophysiological basis of four subtypes of depressive behavior. Front. Psychiatry. 14 (2023).

Shankman, S. A., Sarapas, C. & Klein, D. N. The effect of pre-vs post-reward attainment on EEG asymmetry in melancholic depression. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 79(2), 287–295 (2011).

Bruder, G. E. et al. Electroencephalographic alpha measures predict therapeutic response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant: pre-and post-treatment findings. Biol. Psychiatry. 63(12), 1171–1177 (2008).

Kemp, A. et al. Disorder specificity despite comorbidity: resting EEG alpha asymmetry in major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychol. 85(2), 350–354 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft preparation. R.R.: Project administration, writing—original draft preparation. A.L.H.: Formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. A.Z.: Formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. S.K.: Project administration, writing—review and editing. N.K.: Investigation. J.P.C.: Formal analysis, supervision, writing—review and editing. A.P.: Supervision, writing—review and editing. M.M.A.: Conceptualization, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazemi, R., Rostami, R., Hadipour, A.L. et al. Effect of DLPFC rTMS on anhedonia and alpha asymmetry in depressed patients. Sci Rep 15, 899 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85057-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85057-w