Abstract

Accurate rupture risk assessment is essential for optimizing treatment decisions in patients with cerebral aneurysms. While computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has provided critical insights into aneurysmal hemodynamics, most analyses focus on blood flow patterns, neglecting the biomechanical properties of the aneurysm wall. To address this limitation, we applied Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI) analysis, an integrative approach that simulates the dynamic interplay between hemodynamics and wall mechanics, offering a more comprehensive risk assessment. In this study, we used advanced FSI techniques to investigate the rupture risk of middle cerebral artery bifurcation (MCA) aneurysms, analyzing a cohort of 125 patients treated for a MCA aneurysm at Kepler University Hospital, Linz, Austria. Multivariate analysis identified two significant rupture predictors: High Equivalent Stress Area (HESA; p = 0.049), which quantifies stress distribution relative to the aneurysm surface, and Gaussian curvature (GLN; p = 0.031), which captures geometric complexity. We also introduce the HGD index, a novel composite metric combining HESA, GLN, and Maximum Wall Displacement, designed to enhance predictive accuracy. With a threshold of 0.075, the HGD index exhibited excellent diagnostic performance; in internal validation, 24 of 25 ruptured aneurysms surpassed this threshold, yielding a sensitivity of 0.96. In a 5-fold cross validation the reliability of results was confirmed. Our findings demonstrate that the HGD index provides superior rupture risk stratification compared to conventional single-parameter models, offering a more robust tool for the assessment of complex aneurysmal structures. Further multicenter studies are warranted to refine and validate the HGD index, advancing its potential for clinical application and improving patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerebral aneurysms, affecting approximately 2–5% of the global population1, pose a significant risk due to their potential to rupture, leading to subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)2,3,4, a condition with high mortality and morbidity rates5. Identifying factors contributing to aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture is crucial for effective risk assessment and treatment planning. These factors include clinical, morphological, and hemodynamic characteristics2,3,4. In light of the invasiveness and associated risks of current treatment options6, such as surgical clipping and endovascular treatment, accurate rupture risk assessment remains vital for determining the necessity and timing of interventions7.

The advent of advanced medical imaging techniques has increased the detection rates of unruptured cerebral aneurysms, warranting more sophisticated risk assessments to guide therapeutic decisions5,6,7. Traditional risk assessment tools, like the Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score (UIATS) and the PHASES score may have limitations as rupture risk might be underestimated8,9. In addition, these scores do not integrate detailed hemodynamic and structural properties of aneurysms. These properties encompass the mechanical integrity of the aneurysm wall, geometric configuration, and blood flow patterns. Understanding these factors is crucial as they influence the mechanical stresses on the aneurysm wall and the subsequent risk of rupture.

Key properties influencing rupture risk include:

-

Structural mechanical properties: The mechanical integrity of the aneurysm wall, determining its ability to withstand hemodynamic stresses.

-

Morphological properties: Aneurysm shape, size, and orientation, significantly influencing the hemodynamic environment.

-

Hemodynamic properties: Blood flow behavior within the aneurysm, including parameters such as wall shear stress and flow velocity.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a powerful tool for simulating and analyzing blood flow dynamics within aneurysms. This method allows detailed visualization of how variations in flow patterns and forces impact the aneurysm wall, helping to identify potential areas of weakness and assess rupture risk10,11,12,13. Fluid-structure interaction (FSI) analysis further enhances this evaluation by simulating the interplay between blood flow dynamics and the mechanical response of the aneurysm wall, providing a holistic understanding of factors contributing to aneurysm stability and rupture14,15.

Studies using CFD have shown distinct hemodynamic behaviors in ruptured versus unruptured aneurysms10,11,12,13, indicating that hemodynamic factors exert mechanical stimuli on the aneurysm wall that can trigger biological processes leading to growth and rupture16. The geometry of an aneurysm significantly influences these hemodynamic characteristics17, emphasizing the importance of detailed morphological analysis. Despite extensive CFD research on cerebral aneurysms2,3,10,11,12,13,16,18, there is a notable gap in studies focusing on their structural mechanics, some existing research concentrating on abdominal aneurysms19,20and only a few concentrating on cerebral aneurysms14,15,21.

To address these limitations, our study extends previous methodologies by incorporating a broader range of parameters, including detailed structural mechanical properties and FSI. We aim to refine predictive models for aneurysm rupture risk, improving their clinical utility and effectiveness. An internal validation using a dataset of all ruptured and treated middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms from 2023 at our institution demonstrates the predictive accuracy of this comprehensive model, highlighting its potential to enhance clinical decision-making.

By integrating clinical parameters, structural mechanics, hemodynamics, and FSI, this study aims to provide a more precise and sophisticated analysis using routine imaging modalities such as computed tomography angiography (CT-A) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). This advancement in risk assessment holds the potential to improve clinical decision-making and patient management, ultimately leading to better outcomes for individuals with cerebral aneurysms.

Results

Results including exact P-values are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Clinical parameters

Microsurgical or endovascular treatments were performed in 52 and 28 of patients, respectively. The age difference between the ruptured (mean 52.6 years) and stable (mean 70.1 years) groups was highly significant, but there was no significant difference between ruptured and unruptured (treated) (mean 56.3 years) aneurysms. There were no significant differences in gender, smoking, arterial hypertension or chronic alcohol abuse between any of the groups (Mann-Whitney U-test; Table 1).

The cohort of ruptured aneurysms was additionally subdivided into two subgroups with respect to Arterial Hypertension and Smoking Status. Results of Mann-Whitney U-test are presented in supplementary data table A.1.

PHASES score

The mean PHASES score for all patients was 3.94. There was no significant difference between the ruptured group (mean 4.35), the unruptured treated group (mean 3.75), and the stable group (mean 3.45; Mann-Whitney U-test; Table 1).

Hemodynamic parameters

Maximum hemodynamic parameters (WSSmax, OSImax, Vmax, RRTmax), 90 as well as HOSIA were significantly higher between ruptured and stable aneurysms as well as between unruptured (treated) and stable aneurysms. 90th percentile of OSI (OSI90) showed significance between ruptured and stable as well as unruptured and stable aneurysms, whereas the 90th percentile of WSS (WSS90) only showed significance between ruptured and stable aneurysms. Only Vmax and RRT showed a significant difference between ruptured and unruptured (treated) aneurysms. Average values (WSSav, OSIav, Vav) did not show statistically significant differences (Mann-Whitney U-test, Table 2).

Structural mechanical parameters

All parameters (Dmax, ESmax, ESav, MISESmax, MISESav, and HESA) showed significant differences between ruptured and stable aneurysms. The 90th percentile of MISES (MISES90) showed significant differences between all cohorts, the 90th percentile of ES (ES90) showed difference between ruptured and stable as well as unruptured and stable aneurysms. The 90th percentile of D (D90) did not show statistical significance, although the p value between ruptured and stable aneurysms was very close to 0.05. Only Dav did not show statistical significance. Three parameters (ESmax, MISESav and MISESmax) showed differences between unruptured (treated) and stable aneurysms. Only MISESmax was significantly different between ruptured and unruptured (treated) aneurysms (Mann-Whitney U-test, Table 2).

Morphological parameters

All factors (S, AR, SR, NSI, EI, UI, GLN) showed significant differences between ruptured and stable, as well as unruptured (treated) and stable aneurysms. Only NSI and GLN were significantly different between ruptured and unruptured (treated) aneurysms (Mann-Whitney U-test, Table 2).

Given the decreased significant differences between ruptured and unruptured (treated) aneurysms, only ruptured and stable aneurysms were considered in the following steps.

Predictive modeling with uni- and multivariate regression analysis

For uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis, data from ruptured and stable aneurysms were used (Table 3). In univariate analysis, four hemodynamic parameters (WSSmax, OSImax, Vmax, and HOSIA), two structural mechanical parameters (Dmax and HESA), and all morphological parameters were significantly associated with aneurysm rupture. In the subsequent multivariate analysis, none of the hemodynamic parameters maintained significance, thus they were excluded from further sensitivity analysis.

In both univariate and multivariate analyses, the structural mechanical parameter HESA showed a significant difference, with Dmax showing a tendency (p = 0.032 and p = 0.0504, respectively). These two variables were used for further sensitivity analysis.

Among the morphological parameters, GLN was the only significant parameter in multivariate analysis. Additional collinearity assessment revealed that NSI, UI and EI were almost collinear, explaining the high P-values in multivariate analysis. All three quantities are derived from the convex hull of the aneurysms. Thus, GLN was the only morphological variable used for further sensitivity analysis.

Among hemodynamic and structural mechanical parameters maximum as well 90th percentile values show high collinearity with correlation coefficients > 0.8. As maximum values perform better statistically, they are utilized in subsequent univariate and multivariate analyses.

Definition of additional derived parameters

Following the Mann-Whitney U-test, univariate, and multivariate analyses, Dmax, HESA, and GLN were selected for sensitivity analysis. Our aim was not to derive a complex predictive model for aneurysm risk assessment from the regression analysis, as typically a larger dataset size is required for such analyses. Rather, our approach was to identify significant parameters (p-value < 0.05) and manually combine parameters that yielded high discriminative, statistical power, in order to optimize separation on the dataset. Combinations of these parameters (Dmax, HESA, and GLN) were also investigated to improve sensitivity and specificity. Table 4 defines four additional parameters (HG, GD, HGD0, and HGD) and their mean values. The Mann-Whitney U-test indicated significant differences between ruptured and stable aneurysms for all quantities, with unruptured (treated) data included for completeness.

As the maximum of the displacement Dmax may be associated with certain numerical uncertainties we also define alternative parameters to GD and HGD with the 90 percentile, as these values showed good statistical performance in the U-tests in Table 2.

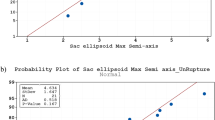

Performance evaluation with sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity and specificity analyses were performed using ROC curves for Dmax, HESA, GLN, and the four additional parameters including AUC values (see Fig. 1). Among single parameters, GLN showed increased sensitivity and acceptable specificity. The HGD parameter produced the best ROC curve. For clinical implementation, threshold sensitivity must be high (> 0.9) while maintaining reasonable specificity. GLN achieved a sensitivity of 0.95 and a specificity of 0.75 at a threshold value of 1. HGD90 showed similar results with a sensitivity of 1 and a specificity of 0.74 at a threshold value of 0.105. HGD showed the best results with a sensitivity of 1 and a specificity of 0.79 at a threshold value of 0.075.

Internal independent threshold validation

To validate these findings, we applied the determined threshold values (GLN = 1, HGD90 = 0.105 and HGD = 0.075) to a dataset of 25 additional ruptured aneurysms. We found that 23 out of 25 ruptured aneurysms exceeded the GLN threshold (sensitivity 0.92), also 23 out of 25 aneurysms cross the HGD90 value (sensitivity 0.92), and 24 out of 25 exceeded the HGD threshold (sensitivity 0.96).

Stratified 5-fold cross validation

In order to further extend the findings of our approach, we conducted an additional stratified 5-fold cross validation (CV) for GLN, HGD90 and HGD. For this we utilized the full dataset of aneurysms excluding the unruptured but treated aneurysms (i.e. 23 original ruptured, 20 stable and 25 ruptured aneurysms used for internal validation, n = 68). The stratified 5-fold CV was conducted by separating the dataset in training and testing data sets 80% and 20% respectively. The p-values as well as the AUC values of the CV are shown in Table 5. GLN, HGD90 and HGD perform in the CV in a similar fashion as before, with p-values < 0.05 and AUC values > 0.9 further underlining the reliability of our findings.

Discussion

In this study, we employed advanced FSI techniques to assess the rupture risk of MCA aneurysms. Our findings demonstrate that integrating morphological, hemodynamic, and structural dynamic aspects significantly enhances risk assessment accuracy. A key innovation in our work is the detailed analysis using High Equivalent Stress Area (HESA). Specifically, we examined the ratio of stress to the total aneurysm area, providing a detailed assessment of stress distribution within the aneurysm. This approach, when combined with morphological parameters, might provide more robust results.

Notably, we introduce the parameter HGD, which combines HESA, GLN and Dmax, as a potential parameter in the ongoing discussion. Unlike single parameters, the HGD offers a more comprehensive and insightful basis for evaluating aneurysm rupture risk. Our results underscore the importance of this parameter and its superiority in the precise analysis of complex aneurysm structures.

Several studies have developed sophisticated models to analyze rupture status in cerebral aneurysms10,11,15,22. Xiang et al. investigated six morphological and seven hemodynamic factors in 119 aneurysms. In multivariate logistic regression analyses, only SR, WSS, and OSI were independently significant factors and were used to create a combined model (AUC 0.89)22. Similarly, in another study, 334 aneurysms were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Significant parameters, including SR, deviation angle, low shear area ratio, and OSI, were ultimately used to develop the “International Aneurysm Rupture Score” (IARS; AUC 0.8110;). Detmer et al. analyzed 1,631 aneurysms using CFD and shape characterization and trained an aneurysm rupture probability model using logistic group Lasso regression. The final model retained 11 hemodynamic and 12 morphological variables (AUC 0.8611;). Yang et al. furthermore showed increased efficacy of their convolutional neural network model by including FSI analysis in their prediction model, raising their sensitivity and specificity from 0.74 to 0.71 to 0.81and 0.82 respectively15.

We similarly used regression analysis to identify significant parameters. We did not define complex regression functions in order to receive a rupture probability score, rather we investigated the statistical differentiation power of our investigated parameters. In our study, however, GLN was the only significant morphological factor, while SR, as demonstrated in other studies, did not reach significance10,11,22. Interestingly, in our study, only structural mechanical factors, and not hemodynamic factors, showed significant differences in multivariate analysis. Additionally, we subdivided the unruptured aneurysm group into an unruptured but treated, and a stable group. This clinically relevant stratification contributes significantly in refining the analysis of patients with unruptured aneurysms. Moreover, in the aforementioned studies, no FSI analysis was performed, and multiple aneurysm locations were investigated10,11,22.

Previous research has highlighted the importance of analyzing rupture risk based on aneurysm location, particularly considering individual morphological and hemodynamic factors of sidewall and bifurcation aneurysms23,24,25. MCA aneurysms, which account for 22–31.5% of all anterior circulation aneurysms24, predominantly rupture at the main bifurcation, with 77% of ruptured cases leading to severe hemorrhage and intracerebral hematoma26,27.

While clinical scoring systems have improved aneurysm stratification, they often lack detailed physiological parameters, limiting their comprehensiveness8,9,28. Rutledge et al. demonstrated that most patients with SAH had small aneurysms with low PHASES scores. Median PHASES score in those patients was 529. Similarly, in this study overall mean PHASES score remained below 5 and there was no association with rupture-status. To address this issue, our study focused on a detailed FSI and morphological analysis of patients with MCA bifurcation aneurysms.

Recent studies indicate that ruptured and growing aneurysms exhibit significantly more complex hemodynamic and morphological characteristics compared to stable aneurysms30,31. To assess rupture risk objectively, we subdivided patients with unruptured aneurysms into treated and stable groups. This subdivision reflects empirical clinical decision-making for treatment, balancing the assessed rupture risk against treatment risk based on clinical scores or patient preferences. This approach indicates that the unruptured (treated) group likely had a higher risk of rupture than the stable group. There is of course no exact information on how close these aneurysms were to rupture. But from a clinical point of view this division might be justified and supported by the fact that in unruptured cases, all mean values of morphologic, fluid, and structural-dynamic parameters were in-between ruptured and stable aneurysms. Additionally, we evaluated ruptured aneurysms to provide a comprehensive comparison across different aneurysm states.

Our findings revealed significant differences in mean values of morphological, hemodynamic, and structural-dynamic parameters between ruptured and stable aneurysms. However, patient-related factors such as smoking status, arterial hypertension and chronic alcohol abuse did not significantly impact the investigated parameters, suggesting these factors did not confound our results. Elsharkawy26and Zhang23 reported similar results.

Several morphological and hemodynamic factors have been identified as critical in predicting MCA aneurysm rupture risk. Aneurysms that deviate from spherical geometry, demonstrating elongation, heightened curvature norms, and overall geometric complexity, are implicated in increased rupture risk16. Our multivariate analysis revealed that GLN was the only morphological parameter significantly associated with rupture risk. While Raghavan could not find a significant difference in Gaussian curvature between ruptured and unruptured aneurysms32, Leemans reported an association with aneurysm growth31. Our results clearly demonstrate that curvature plays a particularly important role, as it considers the entire aneurysm surface.

Hemodynamic parameters, particularly WSS and OSI, have been subjects of debate regarding their association with aneurysm rupture33. Our study suggests that WSS is associated with rupture status (U-test ruptured vs. stable), consistent with findings by Miura and Qiu. Miura et al. analyzed several morphologic and hemodynamic parameters and could demonstrate that WSS was significantly associated with rupture risk34. Similarly, Qiu et al. analyzed 13 morphometric and 5 hemodynamic parameters and confirmed that only WSS was an independent risk factor24. In another study, a “high-versus-low wall shear stress” controversy has been discussed and both high and low WSS may have an impact on aneurysm growth and rupture3. In this study, although there was a tendency towards complex flow in ruptured aneurysms, these results did not reach statistical significance in multivariate analysis.

Distinct vascular responses have been associated with aberrant wall shear stress (WSS) conditions, and two principal pathophysiological pathways proposed: firstly a mural cell-mediated pathway and secondly an inflammatory cell-mediated pathway. Both pathways are believed to contribute to degradative processes that promote proteolytic and oxidative damage, ultimately leading to extracellular matrix degradation and cell death3. Additionally, analysis of aneurysm wall characteristics suggests that small, thin, translucent walls are more frequently associated with high WSS, while thick, atherosclerotic walls tend to develop in regions of low WSS. Nevertheless, the relationship between WSS and aneurysm wall morphology remains a subject of ongoing debate and investigation3,35.

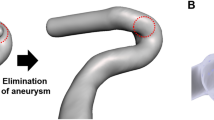

Currently, there are only a few studies that have investigated structural aspects of hemodynamics, mostly in abdominal aneurysms19,20. Cho et al. analyzed 51 patients and reported higher equivalent strains in ruptured aneurysms14. Similarly, in our study ESmax was significantly higher in ruptured aneurysms compared to stable, but not unruptured (treated) aneurysms. In another study, it was demonstrated that the combination of WSS and strain provided a better predictive accuracy compared to a single factor analysis (WSS or strain alone)15. Therefore, we have introduced the derived structural parameter HESA (see Table 6), that calculates high equivalent stress in relation to the total area of the aneurysm. Figure 2 illustrates significant differences between ruptured and unruptured aneurysms (in patients with similar AR), highlighting the diagnostic value of GLN and HESA in rupture risk stratification. Internal validation as well as the stratified 5-fold CV of our results confirmed the robustness of GLN and HGD parameters.

Two exemplary aneurysms (unruptured aneurysm (a), ruptured aneurysm (b)) with similar aspect ratio (AR = 1.7) however significantly different hemodynamic and structural mechanical behaviour (images generated with Paraview 5.11.2 URL: https://www.paraview.org).

Xiang et al.36applied their regression models to unruptured aneurysms measuring how much the aneurysm in question resembles ruptured aneurysms hemodynamically and/or morphologically when compared to their original ruptured training set. They reinterpreted this probability as the Rupture Resemblance Score (RRS), where the higher the score the closer the resemblance to previously known rupture components. Xiang et al. reported that RRS can identify unruptured aneurysms that highly resemble ruptured aneurysms and thus may merit treatment. In a similar way we applied the reported threshold values of GLN (= 1) and HGD (= 0.075) to our cohort of unruptured but treated aneurysms. GLN identifies 82.5% and HGD identifies 64.9% of unruptured aneurysms as ruptured. Thus, similarly to the findings in36, GLN and HGD may help confirm treatment decisions.

Limitations

This study is, however, subject to limitations. One major constraint is the reliance on assumptions regarding the artery’s main shape during aneurysm segmentation, which is limited by current imaging technologies and resolution capabilities. The simulations used in this study cannot account for potential contact with brain tissue, which might influence aneurysm behavior.

Several studies, including Steinman’s 2018 review37 and Dempere-Marco et al.38, have shown minimal differences in WSS between rigid and elastic wall models, suggesting that wall motion has a limited impact on WSS distribution. In these studies, regions of elevated WSS and the overall patterns were largely consistent across both model types. In Nagy et al.39we utilized the same FSI methodology as presented here and results coincide with results from37. For medium and high vessel wall stiffness values, strain remains mostly below 0.1, thus not considerably modifying hemodynamics. However, both Steinman et al. and Dempere-Marco et al. emphasized WSS as the primary hemodynamic metric, without examining the potential influence of wall mechanics on rupture-related structural parameters beyond WSS.

While studies like Dempere-Marco et al. used small samples of large aneurysms (n= 3) and demonstrated negligible wall displacement, we believe that generalizing these findings to all aneurysms is premature. Our study specifically targets MCA bifurcation aneurysms, which may exhibit unique morphological and structural properties compared to other aneurysm locations. Furthermore, our study evaluates a broader range of parameters, including wall displacement and HESA, which were significantly associated with rupture status in our cohort. While strain appears to be low for medium and high stiffness values39, examining the stress on the vessel wall may offer additional insights into rupture risk that surpass those provided by WSS alone. This suggests that further investigation into the role of FSI alone in intracranial aneurysm modeling is warranted. The assumption of a linear elastic material model limits the available range, where this simple material model can be utilized. In Nagy et al.39our FSI methodology was investigated regarding material stiffness14,40,41. When utilizing the lowest reported Young’s modulus value in Cho et al. as well as Cebral et al.14,41, strain values can exceed 0.5, passing well beyond the limits of the applied linear elastic model. However, this low level of stiffness is considered a worst-case scenario for blood vessels. Aneurysms with medium and high stiffness exhibit strain values ranging from approximately 0.02 to 0.1, indicating that a linear stress-strain curve assumption remains applicable. Similar strain values are also reported by Cho et al.14. In future studies, a non-linear approach will be investigated to better describe the material behavior at high strain values. These models may improve structural mechanical results further refining our threshold values identified in this study.

Additionally, the adoption of a constant vessel wall thickness of 0.2 mm, while informed by existing literature17, represents another dimension of uncertainty. Acosta et al. found that mean vessel thickness of MCA aneurysms was around 0.2 and 0.3 mm. As discussed previously for mid and high vessel stiffness, results in39 show that with the assumed constant wall thickness of 0.2 mm the mean strain is low ( < = 0.1). Although wall thickness in individual aneurysms may vary, this average value allows us to maintain consistency across the analysis in this study. With a patient specific distribution ranging mostly between 0.2 and 0.3 mm and thus locally increased wall thickness, strain and stress will be lower. Consequently, a constant wall thickness of 0.2 mm overestimates strain and stress locally. Consequently, HESA as well as HGD might be overestimated resulting in false positive characterization of stable aneurysms as ruptured.

Furukawa et al.42 reported that OSI is higher in thick-walled regions than in thin-walled regions. Building on this insight, an initial simulation using a constant wall thickness could help identify areas likely to be thick or thin, followed by a more patient-specific simulation with variable wall thickness to potentially improve predictive accuracy. We plan to further refine and investigate this approach in future analyses. Additionally, since numerical inaccuracies may arise when using maximum values, we introduced the 90th percentile as a more robust and reliable alternative metric.The empirical data for pulsatile blood flow introduces potential variability, and the lack of comprehensive material property data for individual aneurysms necessitated the use of assumed values for the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. These approximations, while necessary, limit the precision of our models. The study also did not consider outliers in the multivariate regression analysis, which could affect the robustness of our findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the utility of clinical, morphological, and hemodynamic variables in MCA aneurysms, highlighting the complexity of factors contributing to aneurysm stability and rupture. As one of the most extensive studies to date assessing hemodynamic and morphological characteristics, it suggests that clinical parameters alone may be insufficient for accurate rupture risk prediction. Instead, a multifactorial approach incorporating detailed morphological and hemodynamic analyses offers superior predictive accuracy. The GLN and HGD parameters, in particular, exhibited high sensitivity and specificity, supported by internal validation. This research underscores the necessity for an objective, multifactorial analysis in assessing cerebral aneurysm rupture risk, paving the way for more personalized and precise clinical interventions. Future studies should aim to refine these predictive models in a multicenter setting, incorporating advanced imaging technologies and addressing current limitations to further enhance their clinical applicability.

Methods

The study-workflow is summarized in Fig. 3.

Patient data

This study includes patients treated for a single MCA bifurcation aneurysm at the Department of Neurosurgery, Kepler University Hospital, Linz, Austria, from 2016 to 2020. The base cohort consisted of.

-

23 ruptured aneurysms.

-

57 unruptured (treated) aneurysms.

-

20 stable aneurysms.

All ruptured and unruptured aneurysms were managed through either endovascular interventions or microsurgical clipping. Additionally, 20 patients with untreated, unruptured, and stable MCA aneurysms were included based on follow-up imaging in 2023. Stable aneurysms were characterized as aneurysms that remained unchanged in size and shape for at least three years.

To validate our parameters’ relevance in an internal validation step, we included patients with.

-

25 ruptured aneurysms.

treated in 2023 as a control group. Patient-specific parameters such as age, gender, arterial hypertension, smoking status, and alcohol use were extracted from a retrospective medical database. The PHASES score, a rupture rate estimation model, was calculated in each patient as previously described43. We excluded patients with fusiform or dissecting aneurysms.

Image analysis

Medical imaging data were acquired using either DSA, CT-A or MRA-TOF modalities. Aneurysm segmentation was performed using intensity thresholding. The threshold value was visually adjusted for each case individually so that the aneurysm and all connected vessels were clearly defined without showing any holes or artifacts. In some cases, the segmentation was also edited by erasing artifacts or removing adjacent vessels. Next, the largest connected region in the volume was determined and the rest discarded. The remaining segmentation was then triangulated using a marching cubes algorithm, and the resulting surface mesh was remeshed with a finer resolution (0.2 mm), smoothed, and cut along inlet and outlet planes which could be freely positioned along the vessels’ centerlines. The aneurysm surface was defined by placing a plane separating it from the parent vessel. The segmented geometries were converted into surface meshes in STL (Stereolithography) file format. The volumetric fluid hexahedral mesh was generated automatically from these STL files. The optimum fluid volume element edge mesh length was found to be 0.2 mm39. The solid vessel wall mesh was extruded with three layers39from the fluid mesh with a predefined thickness of 0.2 mm17.

Hemodynamic and structural mechanic modeling

The CFD tool OpenFOAM44combined with FSI library solids4Foam21,45, was utilized to solve the unsteady equations numerically. Hemodynamic modeling was based on the principles of mass and momentum conservation using the continuity equation and Navier-Stokes equations. Structural mechanical modeling employed Newton’s second law. Numerical equations were discretized with second order accuracy, except for time discretization, where the first order Euler scheme was utilized. For the solution of the discretized matrix equations the preconditioned conjugate gradient solver was used with a solution convergence tolerance of 1E-6 for fluid dynamic equations and 1E-9 for structural equations. These equations were solved sequentially and coupled using an FSI boundary condition (FSI tolerance of 1E-5). Simulations ran on four CPU cores in parallel on a development laptop (i9-11900 K @ 3.50 GHz with 64 GB RAM). Typical simulation runtimes ranged between approximately 5 and 45 min. The simulation results were validated against experimental data46. Numerical convergence analysis including time step size and mesh independence was conducted and results have been previously published in39.

Inflow boundary conditions were defined by a pulsatile flow profile with a temporal velocity curve derived from published data47. Outflow conditions were time-dependent, based on experimental pressure measurements48. The no-slip condition was assumed along the interior vessel walls. Blood was modeled as a Newtonian fluid with a viscosity of 0.04 Poise and a density of 1.06 g/cm³. The influence of non-Newtonian effects on the viscosity were found to be negligible in39. Simulations were performed over one cardiac cycle (1 s) at 60 beats per minute, discretized into 100-time increments. For structural mechanics, vessel walls were fixed at the inflow and outflow points. Vascular tissue properties were approximated using linear elastic material behavior with a Young’s modulus of 2.49 MPa40and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.4920. The vessel wall thickness was set to 0.2 mm17.

Investigated quantities and parameters

Investigated physical quantities in this work include morphological quantities (size, aspect ratio, size ratio, non-sphericity index, ellipticity-index, undulation index and L2-norm of the Gaussian Curvature), hemodynamic quantities (wall shear stress, oscillatory shear index, vorticity and relative residence time) and structural mechanical quantities (wall displacement, equivalent strain and equivalent Mises stress). Investigated morphological, hemodynamic and structural mechanical parameters are summarized in Table 6.

Where available maximum and average values over the aneurysm sac are analyzed. As maxima can be possibly associated with uncertainties (numerical inaccuracies, etc… ) we also add values at the 90th percentile as an alternative to the maximum value, where this value is available in simulations.

Two new additional parameters HOSIA and HESA are defined in this work, which account for the ratio of the area of high OSI as well as Mises stress to the total aneurysm area. The maximum values of the color legends in Fig. 2 (a) and (b) correspond to the cutoff values defined in Table 6 (OSI = 0.25 and MISES = 1e5 Pa).

The evaluation HOSIA and HESA is conducted as follows:

-

1.

Walk over entire surface of aneurysm.

-

2.

Detect regions with values above cutoff values defined in Table 6.

-

3.

Sum up areas of detected regions.

-

4.

Calculate ratio with total aneurysm area.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to identify parameters predictive of aneurysm rupture risk. For steps 1–3 the base cohort of 23 ruptured, 57 unruptured and 20 stable aneurysms were utilized. For step 4 the cohort of 25 ruptured aneurysms for internal validation were used.

-

1.

Comparative Analysis:

-

Mann-Whitney U-test: Applied to determine significant differences in morphological, hemodynamic, and structural mechanical parameters among ruptured, unruptured (treated), and stable aneurysm groups.

-

2.

Predictive Modeling:

-

Univariate Logistic Regression: The generalized linear model (GLM) was utilized to identify individual parameters significantly associated with rupture risk (p-value < 0.05).

-

Multivariate Logistic Regression: The generalized linear model (GLM) was used to evaluate the combined effect of multiple parameters on rupture risk (p-value < 0.05).

-

3.

Performance Evaluation:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves: Generated to assess the diagnostic performance of identified parameters.

-

Area Under the Curve (AUC): Calculated to assess the predictive accuracy of each parameter.

-

Definition of optimum threshold values.

-

Sensitivity and specificity evaluation.

-

4.

Internal Independent Threshold Validation:

-

An additional control cohort of 25 ruptured aneurysms treated in 2023 was used to validate the predictive thresholds established from the primary analyses.

-

5.

5-fold Cross Validation:

-

In order to further improve the reliability and credibility of our findings, after establishing the best parameters, an additional 5-fold cross validation is performed with GLM on the full dataset (23 original ruptured, 20 stable and 25 ruptured aneurysms for internal validation) excluding unruptured but treated aneurysms. P-values as well as AUC values in the regression analysis are calculated and compared to previous findings.

Ethical considerations: This study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission der medizinischen Fakultät der Johannes Kepler Universität; EK Nr: 1129/2022). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent from patients was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the research.

The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Ethikkommission der medizinischen Fakultät der Johannes Kepler Universität: 1129/2022.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dhar, S. et al. Morphology parameters for Aneurysm Rupture Risk Assessment. Neurosurgery 63, 2, 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000316847.64140.81 (2008).

Jirjees, S., Htun, Z. M., Aldawudi, I., Patwal, P. C. & Khan, S. Role of Morphological and Hemodyanmic Factors in Predicting Intracranial Aneurysm Rutpure: A Review, Cureus, 12, no. 7: e9178 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9178

Meng, H., Tutino, V. M., Xiang, J. & Siddiqui, A. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of Hemodyn. With intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 35, 7, 1254–1262. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3558 (2014).

Japan Investigators, U. C. A. S. et al. The natural course of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in a Japanese cohort. N Engl. J. Med. 366, 2474–2482. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1113260 (2012).

Hoh, B. L. et al. 2023 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, Stroke, 54, 7:e314-e370 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

Hackenberg, K. A. M., Hänggi, D. & Etminan, N. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 49, 9, 2268–2275. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021030 (2018).

Etminan, N. et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur. Stroke J. 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873221099736 (2022).

Feghali, J. et al. Application of unruptured aneurysm scoring systems to a cohort of ruptured aneurysms: are we underestimating rupture risk? Neurosurg. Rev. 44 (6), 3487–3498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01523-3 (2021).

Hernández-Durán, S., Mielke, D., Rohde, V. & Malinova, V. Is the unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score (UIATS) sensitive enough to detect aneurysms at risk of rupture? Neurosurg. Rev. 44, 2, 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-020-01246-x (2021).

Jiang, P. et al. A Novel Scoring System for rupture risk stratification of Intracranial aneurysms: a hemodynamic and morphological study. Front. Neurosci. 12, 596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00596 (2018).

Detmer, F. J. et al. Development and internal validation of an aneurysm rupture probability model based on patient characteristics and aneurysm location, morphology, and hemodynamics. Int. J. CARS. 13, 1767–1779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-018-1837-0 (2018).

Detmer, F. J. et al. Development of a statistical model for discrimination of rupture status in posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Acta Neurochir. 160, 1643–1652 (2018).

Fan, J. et al. Morphological-hemodynamic characteristics of Intracranial Bifurcation Mirror aneurysms. World Neurosurg. 84 (1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.02.038 (2015).

Cho, K. C., Yang, H., Kim, J. J., Oh, J. H. & Kim, Y. B. Prediction of rupture risk in cerebral aneurysms by comparing clinical cases with fluid-structure interaction analyses. Sci. Rep. 10, 1:18237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75362-5 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Rupture risk prediction of cerebral aneurysms using a novel convolutional neural network-based deep learning model. J. Neurointerv Surg. 15, 2, 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018551 (2023).

Soldozy, S. et al. The biophysical role of hemodynamics in the pathogenesis of cerebral aneurysm formation and rupture. Neurosurg. Focus. 47, 1. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.4.FOCUS19232 (2019).

Acosta, J. M. et al. Effect of aneurysm and patient characteristics on intracranial aneurysm Wall Thickness. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 775307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.775307 (2021).

Cebral, J. R. et al. Clinical application of image-based CFD for cerebral aneurysms. Int. j. numer. method. biomed. eng., 27, 977–992 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.1373. PMID: 21822465.

Gasser, T. C., Auer, M., Labruto, F., Swedenborg, J. & Roy, J. Biomechanical rupture risk assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: model complexity versus predictability of finite element simulations. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 40, 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.04.003 (2010).

Reeps, C. et al. The impact of model assumptions on results of computational mechanics in abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc Surg. 51, 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.048 (2010).

Oliveira, I. L., Cardiff, P., Baccin, C. E. & Gasche, J. L. A numerical investigation of the mechanics of intracranial aneurysms walls: assessing the influence of tissue hyperelastic laws and heterogeneous properties on the stress and stretch fields. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 136, 105498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105498 (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Hemodynamic–morphologic discriminants for intracranial aneurysm rupture. Stroke 42, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592923 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Morphological variables Associated with ruptured Middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery 85 (1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy213 (2019).

Qiu, Y. et al. Combining Machine-Measured Morphometric, Geometric, and Hemodynamic Factors to Predict the Risk of Aneurysm Rupture at the Middle Cerebral Artery Bifurcation. World Neurosurg., 185, e484-e490 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2024.02.059

Wang et al. Risk factors for the rupture of bifurcation intracranial aneurysms using CT angiography. Yonsei Med. J. 57, 5, 1178–1184. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1178 (2016).

Elsharkawy, A. et al. A new, more accurate classification of middle cerebral artery aneurysms: computed tomography angiographic study of 1,009 consecutive cases with 1,309 middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery 73 (1), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000429842.61213.d5 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Morphological predictors of middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysm rupture. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 192, 105708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105708 (2020).

Kailaya-Vasan, A. et al. Current decision support tools fail to agree or predict therapeutic decisions in a single cohort of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir. 164, 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-021-04852-w (2022).

Rutledge, C. et al. Small aneurysms with low PHASES scores account for most subarachnoid hemorrhage cases. World Neurosurg. 139, e580–e584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.074 (2020).

Chung, B. J. et al. Identification of hostile hemodynamics and geometries of cerebral aneurysms: a case-control study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39, 10, 1860–1866. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5764 (2018).

Leemans, E. L. et al. Comparing morphology and hemodynamics of stable-versus-growing and grown intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 40, 12, 2102–2110. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6307 (2019).

Raghavan, M. L., Ma, B. & Harbaugh, R. E. Quantified aneurysm shape and rupture risk. J. Neurosurg. 102, 2, 355–362. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0355 (2005).

Cho, K. C. The current limitations and Advanced Analysis of Hemodynamic Study of Cerebral Aneurysms. Neurointervention 18, 2, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.5469/neuroint.2023.00164 (2023).

Miura, Y. et al. Low wall shear stress is independently associated with the rupture status of middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke 44, 2, 519–521. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.675306 (2013).

Rajabzadeh-Oghaz, H., Siddiqui, A. H., Asadollahi, A., Kolega, J. & Tutino, V. M. The association between hemodynamics and wall characteristics in human intracranial aneurysms: a review. Neurosurg. Rev. 45, 1, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01554-w (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Rupture resemblance score (RRS): toward risk stratification of unruptured intracranial aneurysms using hemodynamic-morphological discriminants. J. Neurointerv Surg. 7, 7, 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011218 (2015).

Steinman, D. A. & Pereira, V. M. How patient specific are patient-specific computational models of cerebral aneurysms? An overview of sources of error and variability. Neurosurg Focus. ;47(1):E14. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.4.FOCUS19123. PMID: 31261118.

Dempere-Marco, L. et al. CFD analysis incorporating the influence of wall motion: application to intracranial aneurysms. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 9 (Pt 2), 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/11866763_54 (2006).

Nagy, J. et al. Fluid–structure Interaction simulations of the initiation process of cerebral aneurysms. Brain Sci. 14, 977–991. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14100977 (2024).

Toth, B. K. The mechanical interaction between the red blood cells and the blood vessels, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Budapest (2012).

Cebral, J. R. et al. Wall Mechanical Properties and Hemodynamics of Unruptured Intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 9, 1695–1703. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4358 (2015).

Furukawa, K. et al. Hemodynamic characteristics of hyperplastic remodeling lesions in cerebral aneurysms. PLoS One 13 Pt. 1, e0191287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191287 (2018).

Greving, J. P. et al. Development of the PHASES score for prediction of risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a pooled analysis of six prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. 13 (1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70263-1 (2014).

Weller, H. G., Tabor, G., Jasak, H. & Fureby, C. A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object orientated techniques. Comput. phys. 12, 6, 620–631. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.168744 (1998).

Cardiff, P. et al. Ž., An open-source finite volume toolbox for solid mechanics and fluid-solid interaction simulations, arXiv:1808.10736v2, (2018). available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.10736

Nagy, J. et al. Methods, validation and clinical implementation of a Simulation Method of Cerebral aneurysms. JBEB 10, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.11159/jbeb.2023.003 (2023).

Lorenzetti, F., Suominen, S. & Tukianen, E. Evaluation of Blood Flow in Free Microvascular flaps. J. Reconstr. Microsurg Open. 17, 3, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-14347 (2001).

Blanco, P., Müller, L. & Spence, D. Blood pressure gradients in cerebral arteries: a clue to pathogenesis of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2, 3, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2017-000087 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research subsidies granted by the government of Upper Austria via the FFG (Austrian Research Promotion Agency) [grant number 872604 (Project MEDUSA) as well as grant number FO999895610 (Project ARES)].

RISC Software GmbH is Member of UAR (Upper Austrian Research) Innovation Network. Supported by Johannes Kepler Open Access Publishing Fund and the federal state Upper Austria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study Conception and design: JN, MaG, WF, ST. Verification of the analytical methods: JN, WF, MaG, ZM, AG. JM. Data collection: WF, MG, JO, NS, MSo, PR. Analysis and interpretation of results: JN, MaG, PR, AG, ZM, WF, ST, JM. Design of the model and the computational framework: AM, SK and ST. Draft manuscript preparation: JN, MaG, PR, HS. Supervision of the project: JN, MaG, MG, ZM, AG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contribution statement

The Authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study Conception and design: JN, MaG, WF, ST. Verification of the analytical methods: JN, WF, MaG, ZM, AG. JM. Data collection: WF, MG, JO, NS, MSo, PR. Analysis and interpretation of results: JN, MaG, PR, AG, ZM, WF, ST, JM. Design of the model and the computational framework: AM, SK and ST. Draft manuscript preparation: JN, MaG, PR, HS. Supervision of the project: JN, MaG, MG, ZM, AG.

All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagy, J., Fenz, W., Thumfart, S. et al. Fluid structure Interaction analysis for rupture risk assessment in patients with middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Sci Rep 15, 1965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85066-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85066-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Confocal Raman microspectroscopy imaging reveals structural protein reorganization in human intracranial aneurysm tissue

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Machine Learning-based Prediction of Temporal Velocity-Informatics (TVI) Variables for Accelerated Characterization of Intracranial Aneurysms’ Rupture Status

Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research (2025)