Abstract

To assess the suitability of Transformer-based architectures for medical image segmentation and investigate the potential advantages of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in this domain. We analyze the limitations of the Transformer, which models medical images as sequences of image patches, limiting its flexibility in capturing complex and irregular tumor structures. To address it, we propose U-GNN, a pure GNN-based U-shaped architecture designed for medical image segmentation. U-GNN retains the U-Net-inspired inductive bias while leveraging GNNs’ topological modeling capabilities. The architecture consists of Vision GNN blocks stacked into a U-shaped structure. Additionally, we introduce the concept of multi-order similarity and propose a zero-computation-cost approach to incorporate higher-order similarity in graph construction. Each Vision GNN block segments the image into patch nodes, constructs multi-order similarity graphs, and aggregates node features via multi-order node information aggregation. Experimental evaluations on multi-organ and cardiac segmentation datasets demonstrate that U-GNN significantly outperforms existing CNN- and Transformer-based models. U-GNN achieves a 6% improvement in Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and an 18% reduction in Hausdorff Distance (HD) compared to state-of-the-art methods. The source code will be released upon paper acceptance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, machine learning and deep learning have been extensively applied to research in the biological field1,2,3,4,5,6, demonstrating remarkable performance especially in the areas of cancer-related analysis and prognosis. In the field of medical image segmentation7,8,9, the classic methods are a series of U-shaped CNN networks10,11 represented by U-Net12,13. The feature size of its input and output layers is equal to the width and height of the image. By leveraging the inductive bias14 of CNNs, it extracts the local features of the image layer by layer to output segmentation results with the same width and height as the image. However, in recent years, the Transformer15 has achieved remarkable success in the field of computer vision. Some works have harnessed the powerful global modeling capabilities of the Transformer, achieving impressive results in various fields such as healthcare, microbiology, and industrial defect detection16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Some works introduce the Transformer into the field of medical image segmentation, such as TransUnet23 and Swin Unet24. These works successfully lead medical image segmentation to a new level by taking advantage of the transformers global dense modeling capability. Nevertheless, both the classic CNNs and the Transformer treat the image as a grid or a regularly arranged sequence, which lacks flexibility and difficultly capture the human tumor structure regions with complex topological structures25 in medical images.

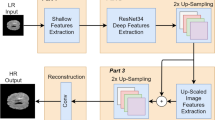

We critically examine the suitability of Transformers and CNNs for medical image segmentation, where the upper limit of the regular modeling of the Transformer and CNN is not high. Even after a large pre-training26,27,28, it’s still difficult for transformers to learn high-level complex features. We focus on a GNN network29,30,31,32 architecture that naturally have a complex topological structure.For example, the research33 demonstrates that Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) possess the capability of unraveling and reallocating heterogeneous information within both the topological space and the attribute space. Some successful works have introduced the Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture into the field of medical images. For instance, SG-Fusion34 has constructed a hybrid model of Transformer and GNN, which significantly enhances the prognostic indicators of gliomas. Another work that combines Transformer and GNN35 has achieved state-of-the-art qualitative and quantitative results in the domain of short-axis PET image quality enhancement. We find that GNNs can also serve as backbone architectures for medical image segmentation, emerging as strong competitors to CNNs and Transformers, and innovatively propose U-GNN, aiming to utilize the powerful topological modeling ability of graph neural networks (GNNs) to fit complex human structures to be segmented, such as tumors and organs. As far as we know, U-GNN is the first U-shaped architecture fully based on GNNs, which pioneerly introduces graph neural networks into the field of medical image segmentation.

We respect the backbone structure of U-Net, it has a natural advantage for medical image segmentation. The U-GNN we proposed is also U-shaped macroscopically. The feature size of the input and output layers of the network is equal to the size of the image. Particularly, the U-shaped network of U-GNN is stacked by a series of original Vision GNN blocks. In each Vision GNN block: the image features are firstly divided into multiple image patch nodes. Subsequently, these nodes undergo graph structure learning36,37,38 to determine how node pairs should be directly connected, thereby establishing the graph topology. Different from previous naive works, we innovatively propose the concept of the multi-order similarity receptive field39,40, which reveals that the first-order similarity between two nodes themselves is not sufficient to represent complex feature relationships, and when calculating the similarity, it is also necessary to consider whether the surrounding nodes are similar, which is particularly important in the scenario where a large area of medical images has a black-and-white structure. We call this novel graph construction method multi-order similarity graph construction, which accurately describes the relationship between image nodes. After the graph is constructed, we propose a global-local combined nodes information aggregation41,42 method called multi-order information aggregation, which can fully enable the information interaction and update between nodes and their neighbor nodes feature.

We conduct standard experiments on multi-organ43 and cardiac segmentation datasets44. The experimental results fully demonstrate that the proposed U-GNN method exhibits excellent segmentation accuracy and robust generalization ability. Overall, the contributions of our proposed U-GNN are mainly reflected in the following:

-

We construct a U-shaped neural network based on graph neural networks for the first time and apply it to medical image segmentation. This innovative attempt is unprecedented in this field.

-

Aiming at the characteristics of medical image segmentation, we propose a multi-order similarity graph construction method, which can describe complex scenarios that cannot be described by the Transformer and accurately construct a Graph at the image feature level.

-

We propose a multi-order information aggregation method, which fully enables information interaction between nodes and iterates the Graph at the image feature level.

-

A large number of experiments prove that the U-GNN we proposed far surpasses all previous methods based on CNNs or Transformers.

Methods

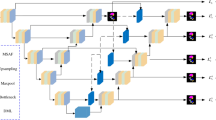

U-GNN overall structure

U-GNN presents a U-shaped structure as a whole, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The size of the input image is consistent with that of the output segmented image. Breaking it down, U-GNN can be regarded as a left-right symmetric encoder45-latent space46-decoder47 structure, and all these three structures are stacked by the most fundamental Vision GNN blocks.

In the encoder stage, the image feature input data with a dimension of C and a resolution of \(H\times W\) is fed into a layer structure stacked by three consecutive Vision GNN modules for multi-scale representation learning. In each layer of the network, the Vision GNN blocks are of equal size, and when the image updates its features within them, both the feature dimension and the resolution remain unchanged. Between layers, there is a downsampling operation, which downsamples the width and height of the image by a factor of two. To compensate for the information loss caused by the downsampling, the dimension of the image features will be doubled simultaneously. The above process is repeated three times in the encoder, and ultimately, both the width and height of the medical image are compressed to one-eighth of their original size.

In the latent space layer, the image nodes pass through \(n_4\) Vision GNN blocks. The characteristic of this stage is that the number of nodes is relatively small (1/64 of that in the input layer), but the feature dimension of the nodes is large, which is suitable for learning some high-level and abstract image features.

The decoder is similar to the encoder but symmetric, and it is also constructed based on Vision GNN blocks at first. The difference is that between different layers of the decoder, the deep features of the image will be upsampled. This layer reshapes the feature maps of adjacent dimensions into feature maps with a higher resolution, achieving the effect of 2-times upsampling. However, at the same time, the dimension of the image features is correspondingly reduced to half of the original dimension. The above process is repeated three times in the decoder, and finally, the features of the medical image are restored to the same size as the input, that is, the final segmentation result map is obtained.

In addition, it should be noted that, similar to U-Net, U-GNN introduces the skip connection mechanism with the aim of organically combining the multi-scale features extracted by the encoder with the upsampled features. Specifically, the features of the shallow layers (Layers 1, 2, and 3) are concatenated with the features of the deep layers (Layers 5, 6, and 7) through skip connections and participate in the feature learning of the deep layers together. This can effectively alleviate the problem of spatial information loss caused by the downsampling process, especially in terms of supplementing high-frequency details. This is because empirical evidence shows that the model tends to learn high-frequency detail information in the shallow layers and low-frequency abstract overall information in the deep layers.

Multi-order similarity graph construction

The U-GNN is constructed by stacking the basic components of the Vision GNN block. Figure 2 shows the specific structure of a single Vision GNN block. Each Vision GNN block consists of a LayerNorm (LN) layer, a parallel structure of Local Graph and Global Graph, Node Aggregation, a residual connection, and a non-linear MLP. All of the process can be mathematically expressed as follows:

where \(x^l\) is the input image feature of the \(l\)-th layer, which is initially embedded into the node sequence \(\hat{x}^l.\) \(G\) is the graph structure learning function that constructs the image into a graph; \(F\) is the function for node information aggregation and update after graph construction; FFN is the feed-forward network.

Before introducing the graph construction method G, it’s imperative to introduce the concept of the multi-order similarity receptive field. Let \(\textbf{X} = [\textbf{x}_1, \textbf{x}_2, \ldots , \textbf{x}_N]\) be a token sequence, where \(\textbf{x}_i \in \mathbb {R}^d\) and N is the number of graph nodes. For a node \(\textbf{x}_i\), its neighborhood \(\mathcal {N}(i)\) with radius r is \(\mathcal {N}(i)=\{j: |j-i|\le r, j\in \{1,\ldots ,N\}\}\). Define the aggregation of neighborhood \(\mathcal {N}(i)\) as \(\textbf{m}_i=\frac{1}{|\mathcal {N}(i)|}\sum _{k\in \mathcal {N}(i)}\textbf{x}_k\). The multi-order similarity receptive field SRF(i, j) between nodes \(\textbf{x}_i\) and \(\textbf{x}_j\) is defined by the cosine similarity of their neighborhood aggregations:

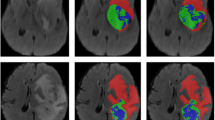

The multi-order similarity receptive field is of paramount importance in medical image segmentation. As illustrated in Fig. 3, medical images typically feature a monotonous background of black, white, and gray tones. In such cases, the inherent first-order similarity between different image patches often fails to accurately represent the true relationships. For instance, in Fig. 3, two white nodes are presented, one originating from a tumor region and the other from healthy tissue. However, their individual features often exhibit a high degree of similarity, as they are both white pixel patches. In traditional similarity calculations, these two patches would be characterized as highly similar. Nonetheless, if the concept of the multi-order similarity receptive field is introduced, rather than solely considering the similarity between the two image patches, the similarity of the surrounding pixel patches is also taken into account. Consequently, the disparity between them becomes evident, clearly indicating that one is from the tumor region and the other from healthy tissue.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we divide the channel-wise image features into two branches: one branch participates in global graph, while the other is used for local graph. In the global graph, each image patch node computes its first-order similarity with all other nodes, and the top eight most similar nodes are selected as neighbors. This reflects the first-order similarity between the current node and its most relevant peers, as previously described. In contrast, the local graph connects each node only to its immediate or second-order neighbors in spatial proximity, enabling effective aggregation of local context.

Importantly, we introduce multi-order similarity through a channel allocation mechanism without incurring any additional computational overhead. In the shallow layers of the network, more channels are allocated to the local graph and fewer to the global graph; this allocation is reversed in the deeper layers, where more channels are assigned to the global graph. Consequently, nodes that initially participate in the local graph at shallow levels are naturally incorporated into the global graph at deeper layers. Since these nodes have already aggregated local information, their first-order similarity computations in deeper layers essentially equal to higher-order similarity with a larger receptive field. This allows the model to better represent complex and irregular objects.

Notably, this channel allocation strategy introduces multi-order similarity at no extra computational cost, since the remaining channels would otherwise be subject to their own intrinsic processing, regardless of the proposed design.

Multi-order node information aggregation

After the construction of the graph is completed, it’s crucial to design an effective node information update mechanism. Similar to Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), when a Graph Neural Network (GNN) updates node information at the k-th layer, the process can be abstractly described in the following way:

where \(M\left( x_i^k\right)\) represents the set of neighbors of node \(i\) at the k-th layer; \(g\) represents the node feature aggregation function, and \(\psi\) represents the node feature update function; \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) are both learnable matrices. In the context of U-GNN, we have proposed the following node update formula:

where \(x_i^l\) is the feature vector of node \(i\) at layer \(l\), \(x_j^l\) represents the feature vectors of the neighbors of node \(i\) at layer \(l\), \(W\) is a learnable weight matrix, \(\text {Concat}\) is the concatenation operation, \(\max\) computes the maximum value element-wise, \(\text {mean}\) computes the average value element-wise, and \(\text {linear}\) is a linear transformation.

The first term in the concatenation is \(x_i^l\), which ensures that the updated node feature \(x_i^{l + 1}\) retains the original information of the node itself. In graph neural networks, the self-information of a node is crucial as it represents the inherent characteristics of the node. By including \(x_i^l\), we prevent the loss of important node-specific information during the update process. The second term \(\max \left( x_j^l-x_i^l\right)\) captures the maximum difference between the node \(i\) and its neighbors. It helps the model to distinguish the node from its neighbors. If a node has a large difference from its neighbors in some feature dimensions, this term will highlight those differences. The third term \(\text {linear}\left( \text {mean}\left( x_j^l\right) \right)\) aggregates the information from the neighbors of node \(i\). The mean operation \(\text {mean}\left( x_j^l\right)\) computes the average feature vector of the neighbors, which gives a summary of the collective characteristics of the neighborhood. The linear transformation \(\text {linear}\) further maps this aggregated information to a suitable feature space. Let \(\text {mean}\left( x_j^l\right) =\frac{1}{|N(i)|}\sum _{j\in N(i)}x_j^l\), and \(\text {linear}(z)=Az + B\) where \(A\) is a matrix and \(B\) is a bias vector. This aggregation helps the node to incorporate the overall information of its neighborhood, which is essential for learning the global structure of the graph.

Results

Experiment setting

The U-GNN is primarily experimentally validated on two mainstream public medical image segmentation datasets, namely Synapse and ACDC. The Synapse multi-organ segmentation dataset encompasses 30 cases, comprising a total of 3779 abdominal clinical axial CT images. Adhering to the sample partitioning method described in the reference literature, 18 samples are allocated to the training set, and the remaining 12 samples are included in the test set. When evaluating the model’s performance, the average Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and the average Hausdorff Distance (HD) are selected as quantitative evaluation metrics. A comprehensive and systematic assessment is conducted on eight abdominal organs, including the aorta, gallbladder, spleen, left kidney, right kidney, liver, pancreas, and stomach.

The Automatic Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge dataset (ACDC) is sourced from data collection of different patients using an MRI scanner. For each patient’s MRI image, the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), and myocardium (MYO) are annotated. This dataset is further divided into 70 training samples, 10 validation samples, and 20 test samples. Similar to the evaluation method employed in the reference literature, on this dataset, we evaluate the involved methods solely through the average DSC (Dice Similarity Coefficient).

The U-GNN is implemented using Python 3.8 and Pytorch 2.1.0. To enhance data diversity, data augmentation techniques such as flipping and rotation are applied to all training instances. The size of the input images is set to 224, and the patch size is determined to be 4. The model training is carried out on an Nvidia RTX3090 GPU with 24GB of memory. Meanwhile, the model parameters are initialized using the weights pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset.

Results on synapse dataset

Table 1 presents the comparison between the U-GNN we proposed and the previous state-of-the-art methods on the Synapse multi-organ CT dataset. The experimental data indicate that our designed Unet-like pure GNN method exhibits the optimal performance. In terms of segmentation accuracy, the average Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) reaches 84.03% and the average Hausdorff Distance (HD) is 17.72%. Compared with TransUnet and the recent Swin Unet method, our algorithm has achieved a significant improvement of approximately 6% in the DSC evaluation metric. Meanwhile, in the HD evaluation metric, our method has achieved a remarkable accuracy improvement of approximately 18%, which strongly demonstrates the excellent performance of this method in edge prediction. Figure 4 shows the segmentation results of different methods on the Synapse multi-organ CT dataset. It’s not difficult to observe from the figure that the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based methods are prone to over-segmentation, which is likely due to the inherent local characteristics of convolutional operations. In this study, we have demonstrated that by parallelizing the local Graph Neural Network (GNN) and the global GNN in the channel dimension and combining them with a U-shaped architecture with skip connections, global and local information can be more effectively integrated, thus obtaining more satisfactory segmentation results. As far as we know, this result represents the current best level in this field.

Results on ACDC dataset

Similar to the application of the Synapse dataset, in this study, the proposed U-GNN is applied to the training process of the ACDC dataset, aiming to achieve accurate medical image segmentation. The relevant experimental results are summarized in Table 3. During the experiment, with the image data in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MR) mode as the input, U-GNN still demonstrated excellent performance, achieving an accuracy of 91.53%. This result fully demonstrates that the method we proposed has good generalization ability and robustness, and can maintain stable and efficient performance under different datasets and imaging modalities.

Ablation study

To substantiate the tangible efficacy of the method proposed in this paper, we conducted ablation experiments on it. Table 4 showcases the outcomes of these ablation experiments. Evidently, on the Synapse dataset, the two proposed sub-methods, namely Multi-order Similarity Graph Construction and Multi-order Node Information Aggregation, both yield improvements to varying extents. When these two sub-methods are employed in conjunction, they form our final U-GNN, which attains state-of-the-art (SOTA) results in the realm of medical image segmentation.

Furthermore, we conduct ablation experiments on the proposed multi-order similarity graph construction to investigate the optimal similarity receptive field size. As shown in Table 5, the worst performance is observed when only pairwise similarities between graph nodes are considered, without incorporating multi-order similarity, resulting in a DSC score of 79.74. Notably, as the similarity receptive field expands, the segmentation performance of U-GNN improves significantly, achieving the highest DSC score of 84.03 when a 3-order receptive field is employed.

Visualization

To gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanism of U-GNN, we visualized the interactions between tumor image patches and other image nodes within the model. As shown in Fig. 5, U-GNN accurately identifies tumor patches at different locations as neighboring nodes. Despite some tumor features being distant or obscured, U-GNN effectively establishes their connections with high accuracy, highlighting its robust ability to capture long-range dependencies in tumor representations.

Conclusion

This paper presents U-GNN, a novel U-shaped encoder-decoder architecture specifically designed for medical image segmentation. The proposed U-GNN is entirely built upon Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). To fully exploit the potential of GNNs in feature learning and information interaction, we employ the Vision GNN blocks as the fundamental unit for feature representation and long-range semantic information exchange. To capture the deep features of medical images, we introduce two innovative methods: Multi-order Similarity Graph Construction and Multi-order Node Information Aggregation. Extensive and in-depth experiments are conducted on multiple tasks, including multi-organ segmentation and cardiac segmentation. The experimental results clearly demonstrate that the proposed U-GNN exhibits superior performance and strong generalization capabilities. Among the current models in medical image segmentation, our approach achieves a significant performance advantage.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author Huimin Xiao upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All the code is available from the first author Huimin Xiao upon request.

References

Cao, Z., Zhu, J., Wang, Z., Peng, Y. & Zeng, L. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis reveals enc1 as a promising prognostic biomarker for tumor microenvironment and therapeutic responses. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 25331 (2024).

Alhussen, A. et al. Early attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with NeuroDCT-ICA and rhinofish optimization (RFO) algorithm based optimized ADHD-AttentionNet. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 6967 (2025).

Sun, D.-Y. et al. Unlocking the full potential of memory t cells in adoptive t cell therapy for hematologic malignancies. Int. Immunopharmacol. 144, 113392 (2025).

Wang, S. et al. Discovery of a highly efficient nitroaryl group for detection of nitroreductase and imaging of hypoxic tumor cells. Organ. Biomol. Chem. 19(15), 3469–3478 (2021).

Yaqoob, A. et al. SGA-driven feature selection and random forest classification for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis: A comparative study. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 10944 (2025).

Wang, G. et al. A skin lesion segmentation network with edge and body fusion. Appl. Soft Comput. 170, 112683 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. Drinet for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37(11), 2453–2462 (2018).

Gao, Y., Zhou, M. & Metaxas, D.N. Utnet: A hybrid transformer architecture for medical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part III 24, 61–71 (Springer, 2021).

Huang, X., Deng, Z., Li, D. & Yuan, X. Missformer: An effective medical image segmentation transformer. arXiv:2109.07162 (2021).

Huang, H., Lin, L., Tong, R., Hu, H., Zhang, Q., Iwamoto, Y., Han, X., Chen, Y.-W. & Wu, J. Unet 3+: A full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 1055–1059 (2020).

Targ, S., Almeida, D. & Lyman, K. Resnet in Resnet: Generalizing residual architectures. arXiv:1603.08029 (2016).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18, 234–241. (Springer, 2015).

Siddique, N., Paheding, S., Elkin, C. P. & Devabhaktuni, V. U-net and its variants for medical image segmentation: A review of theory and applications. IEEE Access 9, 82031–82057 (2021).

Xuhong, L., Grandvalet, Y. & Davoine, F. Explicit inductive bias for transfer learning with convolutional networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2825–2834 (2018)

Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., Weissenborn, D., Zhai, X., Unterthiner, T., Dehghani, M., Minderer, M., Heigold, G., Gelly, S. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Ma, D. et al. Transformer-optimized generation, detection, and tracking network for images with drainage pipeline defects. Comput Aided Civil Infrastruct. Eng. 38(15), 2109–2127 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Large-field objective lens for multi-wavelength microscopy at mesoscale and submicron resolution. Opto-Electron. Adv. 7(6), 230212–1 (2024).

Du, F. et al. An engineered \(\alpha\)1\(\beta\)1 integrin-mediated fc\(\gamma\)ri signaling component to control enhanced car macrophage activation and phagocytosis. J. Controll. Release 377, 689–703 (2025).

Lou, Y. et al. Simultaneous quantification of mirabegron and vibegron in human plasma by HPLC-MS/MS and its application in the clinical determination in patients with tumors associated with overactive bladder. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 240, 115937 (2024).

Song, W. et al. Centerformer: A novel cluster center enhanced transformer for unconstrained dental plaque segmentation. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 26, 10965–10978 (2024).

Luan, S. et al. Deep learning for fast super-resolution ultrasound microvessel imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 68(24), 245023 (2023).

Yu, X. et al. Deep learning for fast denoising filtering in ultrasound localization microscopy. Phys. Med. Biol. 68(20), 205002 (2023).

Chen, J., Lu, Y., Yu, Q., Luo, X., Adeli, E., Wang, Y., Lu, L., Yuille, A.L. & Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv:2102.04306 (2021).

Cao, H., Wang, Y., Chen, J., Jiang, D., Zhang, X., Tian, Q. & Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 205–218 (Springer, 2022).

Zhang, B. & Wolynes, P. G. Topology, structures, and energy landscapes of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112(19), 6062–6067 (2015).

Bao, H., Dong, L., Piao, S. & Wei, F. Beit: Bert pre-training of image transformers. arXiv:2106.08254 (2021).

Chang, W.-C., Yu, F.X., Chang, Y.-W., Yang, Y. & Kumar, S. Pre-training tasks for embedding-based large-scale retrieval. arXiv:2002.03932 (2020).

Li, C., Bi, B., Yan, M., Wang, W., Huang, S., Huang, F. & Si, L. Structurallm: Structural pre-training for form understanding. arXiv:2105.11210 (2021).

Scarselli, F., Gori, M., Tsoi, A. C., Hagenbuchner, M. & Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 20(1), 61–80 (2008).

Wu, J., Li, J., Zhang, J., Zhang, B., Chi, M., Wang, Y. & Wang, C. PVG: Progressive vision graph for vision recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2477–2486 (2023).

Han, K., Wang, Y., Guo, J., Tang, Y. & Wu, E. Vision gnn: An image is worth graph of nodes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 8291–8303 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Graphformers: Gnn-nested transformers for representation learning on textual graph. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 28798–28810 (2021).

Huang, C. et al. Flow2gnn: Flexible two-way flow message passing for enhancing GNNs beyond homophily. IEEE Trans. Cybern. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2024.3412149 (2024).

Fu, M. et al. SG-Fusion: A swin-transformer and graph convolution-based multi-modal deep neural network for glioma prognosis. Artif. Intell. Med. 157, 102972 (2024).

Fu, M. et al. A two-branch neural network for short-axis pet image quality enhancement. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27(6), 2864–2875 (2023).

Jin, W., Ma, Y., Liu, X., Tang, X., Wang, S. & Tang, J. Graph structure learning for robust graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 66–74 (2020).

Drton, M. & Maathuis, M. H. Structure learning in graphical modeling. Ann. Rev. Stat. Appl. 4(1), 365–393 (2017).

Sun, Q., Li, J., Peng, H., Wu, J., Fu, X., Ji, C. & Philip, S.Y. Graph structure learning with variational information bottleneck. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 36, 4165–4174 (2022).

Sengupta, A., Pehlevan, C., Tepper, M., Genkin, A. & Chklovskii, D. Manifold-tiling localized receptive fields are optimal in similarity-preserving neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 31 (2018).

Zhou, L., Cai, H., Gu, J., Li, Z., Liu, Y., Chen, X., Qiao, Y. & Dong, C. Efficient image super-resolution using vast-receptive-field attention. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 256–272 (Springer, 2022).

Przydatek, B., Song, D. & Perrig, A. SIA: Secure information aggregation in sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, 255–265 (2003).

Lai, K.-H., Zha, D., Zhou, K. & Hu, X. Policy-GNN: Aggregation optimization for graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 461–471 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Li, J. & Hua, Z. MPSHT: Multiple progressive sampling hybrid model multi-organ segmentation. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 10, 1–9 (2022).

Sakaridis, C., Dai, D. & Van Gool, L. Acdc: The adverse conditions dataset with correspondences for semantic driving scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 10765–10775 (2021).

Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A. & Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39(12), 2481–2495 (2017).

Bojanowski, P., Joulin, A., Lopez-Paz, D. & Szlam, A. Optimizing the latent space of generative networks. arXiv:1707.05776 (2017).

Bagal, V., Aggarwal, R., Vinod, P. & Priyakumar, U. D. MolGPT: Molecular generation using a transformer-decoder model. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62(9), 2064–2076 (2021).

Milletari, F., Navab, N. & Ahmadi, S.-A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV). IEEE, 565–571 (2016).

Fu, S., Lu, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., Shen, W., Fishman, E. & Yuille, A. Domain adaptive relational reasoning for 3d multi-organ segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2020: 23rd International Conference, Lima, Peru, October 4–8, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 23, 656–666 (Springer, 2020).

Hu, X.-Z., Jeon, W.-S. & Rhee, S.-Y. Att-unet: Pixel-wise staircase attention for weed and crop detection. In 2023 International Conference on Fuzzy Theory and Its Applications (iFUZZY). IEEE, 1–5 (2023).

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made significant contributions to the reported work, with distinct roles in data processing, code development, and manuscript writing. They have reached a consensus regarding the submission to the journal and agree to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no interest/Competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All data used in this study are sourced from publicly available datasets. Since the research does not compromise personal interests, involve sensitive information, or have commercial implications, it is exempt from ethical review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, H., Yang, G., Li, Z. et al. GNNs surpass transformers in tumor medical image segmentation. Sci Rep 15, 19842 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00002-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00002-9