Abstract

Current movie recommendation systems often struggle to capture complex user preferences and dynamics, primarily relying on content-based or collaborative filtering techniques. This research introduces a novel deep learning-powered method to enhance movie recommendation models, addressing the limitations of existing systems. By analyzing user behavior records and utilizing movie content elements, our method guarantees the greatest degree of customisation. In this study, we employ Artificial Intelligence (AI), graph-based techniques, and text mining to accurately estimate user preferences. While PageRank ranks the films based on their importance in the individual’s history of surfing, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) predicts the possibility that the movie would be accepted. The experiments employed a dataset of 215 users’ browsing activity in 508 movie pages for evaluation. The presented approach achieved significant enhancement in recommendation precision and recall metrics resulting in 7.15% precision expansion and 5.19% recall growth which indicates its potential implementation in personalized movie recommendation systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

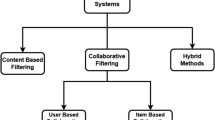

As internet technology advances at a rapid pace, there is an explosion of information on the internet. The recommender system is a basic technique that helps consumers locate the relevant information based on their preferences in the dataset. The Recommender System’s (RS’s) goal is generating recommended items in an automatic manner (CDs, books, movies, music, DVDs, news, web pages) for consumers based on their past behaviour or attributes. These systems can reduce the time of searching items by customers through recommending relevant data. Amazon.com, eBay.com, and Yahoo.com, are some of the websites that use the recommender system technique1,2,3,4,5,6. Recommender systems gather pertinent data and user preferences. Imagine you just signed up for Amazon. The website’s recommendation engine, eager to impress, tries to analyze your potential tastes. But let’s say you haven’t bought anything or browsed much yet. The engine, with little information to go on, stumbles upon a common hurdle: the cold-start problem7,8,9. This means it lacks enough data to suggest items you’d genuinely enjoy. Thankfully, the more you explore Amazon, clicking and searching, the engine gathers clues. Soon enough, personalized recommendations tailored to your interests start popping up, waiting to be discovered. Up until this point, the system is oblivious of the preferences and decisions made by the new user. The power of recommender systems has been witnessed by a multitude of applications and business applications, including online commerce, web intelligence, entertainment, and travel. These applications continue to advance the technology into its mature stage. The several filtering processes, including social-based, hybrid, content-based (CB), context-based, and collaborative filtering (CF) are handled by RSs. The method that recommender systems utilize the most frequently is the CF technique10,11,12,13,14. In the case of the CF-based approach, suggestions are made based on user ratings. For instance, if customers rate a variety of products on an e-commerce website, including a juicer mixer, washing machine, and camera, a RS will make product recommendations to users. The decision-making process for CB filtering is based on past decisions15,16. Because RS will get to know a person’s behavior, if they purchase a computer, it is likely that RS will solely recommend computer-related items. Recommendations in a demographic-based recommender system are derived from human characteristics including location, age, sex, and nationality17,18,19. Due to the fact that hybrid-based recommender systems combine CF, CB filtering, and demographic filtering with a variety of machine learning and computational intelligence technologies and algorithms, they are now effective in e-commerce and web intelligence applications20,21,22. Thus, making a suitable recommendation is a good approach to boost the rate at which particular media material is viewed, improving the impact of online news broadcasting and advertising. Recommendation services for relevant videos are generated using social texts, even though several popular video sharing platforms, like Youtube, Netflix, MySpace, and Google Video, offer this feature. While some video recommendation systems incorporate content and social relationships, many still face challenges in effectively integrating fine-grained content features with complex user browsing history23. The proposed approach distinguishes itself by the novel integration of a CNN-based content preference prediction with a PageRank-based user browsing history analysis. This combination, and the way that the model combines the results of the CNN and PageRank algorithm, allows the recommender system to capture both the semantic content of movies and the dynamic patterns of user behavior, providing a more comprehensive and personalized recommendation experience. The paper offers a brief summary of our main contributions.

-

Development of a novel deep learning architecture to accurately predict user preferences based on their viewing behavior and patterns.

-

Integration of graph analysis techniques with deep learning to create a hybrid recommendation framework that considers both user behavior and movie content.

-

Demonstration of improved recommendation performance through rigorous experimentation, surpassing the accuracy of existing state-of-the-art methods.

The paper follows this progression: Similar works are examined in Sect."Related works". The proposed technique is explained in Sect."Research methods", the implementation results are reported in Sect."Implementation results", and the conclusions are drawn in Sect."Discussion".

Related works

Ahuja et al.24 focused on developing a movie recommender system using K-Means Clustering and K-Nearest Neighbor algorithms, using a Movielens dataset from Kaggle. The system is implemented in Python and shows better RMSE values than existing techniques.

Katarya and Verma25 presented a novel movie recommendation system using cuckoo search optimization and k-means clustering on the Movielens dataset. The RS outperforms existing methods in reliability, efficiency, and personalized movie recommendations, with a 0.68 MAE, a significant improvement from previous work.

Thakker et al.26 discussed the CF algorithm’s applications for the movie recommendation system (MRS), focusing on user-based and item-based approaches. It also discussed machine learning algorithms for movie recommendation and user preference sorting. The paper also discussed past research and future developments in CF recommendation systems, including challenges like cold start, data sparsity, and scalability issues.

Gupta et al.27 aimed to enhance the accuracy and performance of a standard movie filtering technique by focusing on improving result accuracy compared to content-based filtering. The approach utilized K-NN algorithms and collaborative filtering to improve results based on cosine similarity using k-nearest neighbor and a collaborative filtering technique, thereby addressing the limitations of content-based filtering.

Airen and Agrawal28 explored different variations of the nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm for the movie recommender system, using different similarity measures such as cosine, mean squared difference (MSD), Pearson correlation, and adjusted Pearson correlation. These algorithms were evaluated on real data from the MovieLens dataset and compared based on accuracy metrics.

Chauhan et al.29 proposed a combined recommender system that integrated collaborative filtering, content-based filtering, and sentiment analysis of movies. The system recommended movies based on user sentiment, addressing limitations and improving user experience.

Tahmasebi et al.30 introduced a hybrid system that used a deep autoencoder network, incorporating collaborative and content-based filtering, as well as users’ social influence. Data from MovieTweetings was used for evaluation, and the results showed MAE of 0.71, reflecting the model’s effectiveness compared to its previous methods.

Lee et al.31 developed a network-based movie recommender system that used sentiment and emotion information, along with user ratings, to help users choose appropriate movie titles. The system outperformed traditional models and state-of-the-art network-based models, with the proposed IGMC-based models demonstrating superior performance. The findings highlighted the importance of incorporating user sentiment and emotion information in movie recommendation.

Sun et al.32 proposed a social-aware group recommendation approach that considered group-level interest and individual preference. It used a group preference model and a social-aware tolerance and altruism model to capture group members’ social behaviors. User evaluations showed better performance in high group dynamics and for inactive members.

Yadav et al.33 proposed a recommendation system that utilized big data clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) to classify users based on similar interests. It was utilized in e-commerce and website applications, using the MovieLens dataset for the recommendation. The system’s efficiency and accuracy were demonstrated, with a MAE of 0.67, making it the best among existing techniques.

Abderrahmane et al.34 proposed a movie recommendation system using the k-nearest neighbors approach and a collaborative filtering algorithm to help customers find their favorite books and movies in a vast array of genres and types.

Ambikesh et al.35 proposed a movie recommender system using harris hawks optimization (HHO) and k-means clustering. It compared various clustering algorithms, revealing that HHO-k-means consistently outperforms them in terms of precision, recall, MAE, and RMSE, suggesting it may be a more accurate clustering approach.

Zubi et al.36 presented an efficient hybrid movie recommendation system using association rules mining and the KNN algorithm as a classification method. The system used a practical MovieLens dataset and the Apriori algorithm to create candidate lists. The system outperformed existing systems in terms of importance degree and accuracy rate, demonstrating the growing importance of recommendation systems.

Jain and Essah37 proposed a recommendation system for online streaming services like Netflix, based on customer interactions. The system used a collaborative filtering framework and three algorithms: cosine similarity, K nearest neighbors, and Singular Value Decomposition. The results showed RMSE, precision, and recall of the algorithms. The technique was used by e-commerce websites like Amazon, Flipkart, and Mantra to understand customer behavior and recommend products.

Sharma et al.38 presented a hybrid RS based on sparrow clustered (HSC) for improving scalability and performance in recommendation. The authors examined the performance of this system using MovieLens dataset. The method utilized symmetry in collaborative filtering to produce competitive performance metrics with precision at 0.602 and recall at 0.64 and mean absolute error at 0.685 through a metaheuristic optimization of within-cluster sum of squared distances.

The authors of39 introduced deep GraphSAGE as an item recommendation method which uses graph neural networks to boost performance. The authors resolved the over-smoothing issue by combining Jumping Knowledge (JK) connections with Ordinal Aggregation Network (OAN). The results showed better performance than alternative aggregation methods which proved the effectiveness of deep GraphSAGE with JK. Item-based recommendation systems have restrictions when used in situations where comprehensive contextual information is needed.

The authors presented a comparative research on Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and deep multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) when used for collaborative filtering in40. Researchers assessed the capability of these methods to deliver appropriate resources as their main objective. The evaluation included non-linear MLPs together with SVD as methods under study. The research presented valuable information but its findings were constrained by using one dataset and specific evaluation measures.

The authors of41 conducted a renewed study of neural collaborative filtering (NCF) versus matrix factorization (MF) through analysis of embedding combination techniques. The authors showed that dot products achieve better performance than learned similarities from MLPs when using suitable hyperparameter values. The authors emphasized that MLPs become inefficient for practical production settings. The authors found learning dot products with MLPs to be difficult which led them to recommend dot products as the more efficient default approach.

El Alaoui et al.42 presented a review of recommendation techniques for scientific papers that analyzed collaborative filtering versus content-based and hybrid algorithms. The research sought to determine which method would produce the best results for investigators. Research demonstrated that the hybrid technique outperformed all other methods because it handled the issues of cold start and sparseness. The evaluation method uses classical information retrieval metrics to measure user satisfaction although these metrics might not adequately reflect actual user satisfaction.

The authors in43 developed Dynamic Graph Attention Network with Adaptive Edge Attributes (DGAT-AEA) for contextual recommendation systems. The technique updates user and item properties dynamically through dynamic modifications of edge attributes which enables the system to detect complex connections. The experimental outcome indicated acceptable accuracy and performance. The advanced model structure presents limitations in its practical use for real-time applications.

Ziaee et al. developed MoRGH which represents a movie recommender system that utilizes heterogeneous GNNs according to their research in44. The researchers aimed to solve two main issues which involved ignoring supplementary data and struggling with new user and item introductions. The method built a heterogeneous graph structure that utilized GNN and GAE-based models to achieve better RMSE results. The RMSE metric used in the study fails to provide comprehensive evaluation of recommendation quality beyond its specific measurement.

The authors in45 developed heterogeneous graph attention networks for social recommendation systems. The researchers sought better prediction results through adding structured background data to their approach. A new system generated multiple perspective embeddings for users and items which resulted in better performance in HR@k and NDCG@k metrics. The social recommendation approach has potential limitations because it does not extend to all recommendation scenarios.

The authors performed a comparative analysis of filtering approaches for scientific research article recommendations in their work46. The research team conducted an assessment of collaborative filtering and content-based and hybrid methods to determine that hybrid methods were more effective. Table 1 summarizes the studied works.

The reviewed literature shows a reliance on conventional techniques that include collaborative filtering, content-based filtering, and the hybrid systems that integrate the two. Although these methods have achieved reasonable results, they have also brought some problems, including cold start, data sparsity, and inability to capture the dynamic changes of users’ preferences and behaviors. Furthermore, most previous works are devoted to particular techniques or datasets, while the general picture of the field and its difficulties and prospects remain unclear. To overcome these limitations, this research presents a new deep learning method based on the behaviour patterns of the users and the content of the movies.

Research method

In this section, the characteristics of the dataset used in the design and assessment of the proposed recommender model are outlined first. This is followed by a presentation of the steps in the proposed strategy, which recommends movies based on modeling user behavior.

Data

In the current study, use is made of a dataset that comprises the browsing history of 215 users on the IMDb website. This dataset is composed of three tables. The first table delineates user features, describing each user via three attributes: age, gender, and occupation. The second table encapsulates the characteristics of the movies in the dataset, with each data record encompassing genre features, factors, movie summary, year of production, rating, number of votes, and movie duration. Complementing these two tables is a collection of 508 documents in XML format, each of which describes the behavioral characteristics of a user in relation to the movies in the dataset and contains the content information of a movie (the web page related to the movie). Browsing on the site pages by each user is stored as a set of transactions. A transaction record, representing a user’s visit to the movie pages, is stored as < i, j, t, d>. In this quadruple, ‘i’ denotes the user ID, ‘j’ signifies the ID of the movie visited by the user, ‘t’ indicates the page load time, and ‘d’ is the duration of user ‘i’ staying on page ‘j’. During the implementation process, this set of transactions for each user is converted into an adjacency matrix of a directed graph. Browsing by the user is sorted based on time (t) in the database transaction set. Following this, the navigation of the user between different movie pages on the website is represented as the number 1 in the graph’s adjacency matrix. Each vertice of this graph refers to a of page on the site. The presence of an edge from node a to node b in this graph signifies that the target user visited page b subsequent to viewing page a. All dataset instances have been anonymized. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations, specifically the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 45, Part 46, as defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. Table 2 summarizes the specifications of this database.

Proposed method

The focus of the current research is the provision of an efficient solution for recommending movies to users. The proposed method takes into account the set of features available in the user profile and the attractiveness of the movie from the user’s perspective as the basis for recommendation. To achieve this, the presented approach employs a set of text mining and machine learning techniques.

In this research, consideration is given to a user who possesses a set of behavioral records in the context of browsing movie observations on a website. The objective of the proposed method is to recommend movies that align with the user’s interests and behavioral history. The presented approach for offering recommendations to users encompasses three phases (Fig. 1):

-

a.

Content features are processed and the acceptance probability is calculated based on a CNN.

-

b.

Movie pages are ranked based on the PageRank criterion.

-

c.

A probability vector is generated and recommendations are provided.

Based on the diagram depicted in Fig. 1, the input to the proposed model comprises the data of the movie pages on the website and the user’s browsing history on these pages, supplied via the database. This database, besides the list of pages viewed by each user, contains the frequency of the user’s visits to the movie page and the duration of browsing on the viewed pages. This information serves as the input to the proposed method. The initial step in the proposed method involves extracting the content of the movie pages. During this step, the content of each movie page in the database is extracted as a text string. Subsequently, preprocessing operations are carried out to stem words and eliminate ineffective words in the content of the movie pages. Following the execution of preprocessing operations, the TF-IDF solution is employed to extract features of the movie pages. Ultimately, the content features of each movie page are amalgamated with the user’s viewing history information to form a feature matrix for the training data. Based on this data, a CNN model undergoes training. This learning model is designed to predict the probability of movie acceptance by the user for new pages. The outcome of this step is a vector representing the probability of movie acceptance by the user, generated by the CNN model. In the second step of the proposed method, a graph is created that represents the relationships derived from the user’s browsing history on the movie pages of the site. Based on the PageRank criterion, the existing movie pages are ranked. The outcome of this second step is a vector representing the importance of movie pages. In the final step of the presented approach, two vectors - probability (the result of the CNN model) and importance (the result of the PageRank criterion) - are combined to form the final ranking vector. Ultimately, movies that hold the highest rank value in the mentioned vector are recommended to the user as the output of the proposed algorithm. The details of each step in the proposed method will be elaborated on in the following sections.

Processing page content and Building a user model based on CNN

The initial step in the proposed method involves constructing user models based on their browsing history on the movie pages of the website. In the method proposed, content information from the movie pages viewed by the user is utilized in conjunction with the features, the number of views, and the duration of browsing on each movie page, for recommendation purposes.

Consider a database composed of a set of movie pages viewed by various users, along with the time and number of visits to each page by users. Each page has textual content (according to Sect."Data"). The first step in recommendation by the presented approach is to build user models on the basis of the information available in the database. In the proposed method, each user model is described based on a CNN model that has been trained based on the users’ viewing history. The mechanism of constructing a CNN model for users is shown in Fig. 2.

As depicted in Fig. 2, each user has viewed a number of movie pages. In the step of constructing the user model, the texts of each page, including the movie features, are extracted first. Subsequently, the feature vector associated with each web page is formed. This feature vector is composed of two parts. The first part encompasses the TFIDF vector of the web page content. The second part, represented as <Ni, Ti, AU> in Fig. 2, includes the number of page views (Ni), the duration of browsing page i by user U (Ti), and finally the user attributes (AU). Following the extraction of the feature vectors of each movie page, these vectors constitute the behavioral records of user U. These records serve as training data for the CNN model. Ultimately, the trained CNN model corresponds to the user model. The details of constructing user models based on this mechanism are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

As stated, the initial step in the process of constructing user models involves extracting the features of the movie pages. To achieve this, the content features of each movie page need to be represented as vectors of equal length. In the method proposed, the TD-IDF strategy is employed to carry out this task. Initially, the ineffective words present in the text of each page are identified and eliminated. Ineffective words are words such as ‘be’, ‘from’, ‘as’, etc., that do not reflect any key concept in their presence in the text. Consequently, removing these words from the texts of the pages can enhance the feature extraction process.

Following the removal of ineffective words from the texts of the pages, the process of stemming is executed on the result. This is because the use of stemmed words restricts the dimensions of the word vector, or in other words, the feature vector. Accordingly, for each word in the texts of the pages, suffixes and prefixes are disregarded. In the presented approach, the Porter algorithm is employed for the stemming operation. After executing the aforementioned process for each text, a list of unique words from the texts of the movie pages existing in the database is generated. This list, which includes the total root words of the database, is utilized to describe the content of each movie page.

Imagine a database represented by a vector F containing terms like w1, w2, and so on. Each page’s content can be characterized by assigning weights to a feature vector W, where each weight ti reflects the significance of term wiin vector F. To capture the essence of each movie page, we extract the unique words from the text and employ the TF-IDF technique. In this way, we analyze each page’s content based on the presence of unique words. Subsequently, we assign weights to each word using the TF-IDF formula. For instance, the weight of a word w is calculated as47:

Instead of counting word repetitions (Tw) and relying on raw counts (TD), this method introduces a normalized measure called TF-IDF to weigh how important each word (w) is for a specific movie page. This considers both how often the word appears within the page (frequency) and how rare it is across all pages in the database (Nw). These weights are then stored in a feature vector (W), creating a matrix with one row per movie page and each column representing a TF-IDF value. This essentially transforms each page into a vector summarizing its content characteristics based on the unique presence of words. Following the extraction of the TFIDF matrix of the samples, the features ‘number of visits to the page’, ‘duration of page review’, and the user index features are appended to the records of this matrix. This ensures that the user’s behavioral features are also documented in the feature matrix. It is noteworthy that in the method proposed, the features of gender and profession of users are converted to numerical form prior to their inclusion in this vector.

Following the construction of the feature matrix associated with the user, a CNN model is employed for training and constructing user models. It should be noted that each record in the user feature matrix must possess a target value (output) to enable the learning model to execute the training operation based on it. For this purpose, the target value in the training data for each training record is determined as follows: If a movie page has been viewed by the user more than once or the average duration spent on the page exceeds 1 min, the value ‘1’ is recorded as the training target for the output corresponding to the features of this page. The target category ‘1’ signifies a category of pages that are likely to be accepted by the user. Conversely, for the output corresponding to the features of this page, the value ‘2’ is recorded as the training target. The target category ‘2’ represents a category of pages that are probably not of interest to user U. The architecture of the suggested CNN for constructing user behavioral models is depicted in Fig. 3.

As depicted in Fig. 3, the CNN model takes the collected features for the movie and user as input in the form of a vector. This CNN model generates one-dimensional feature maps using three successive one-dimensional convolution components. The initial convolution component comprises 16 filters and is tasked with extracting partial patterns from the data. Concurrently, the second and third convolution components utilize 32 and 64 filters, respectively, to extract deeper feature maps from the data. Each convolution component in the proposed CNN is composed of three layers: a one-dimensional convolution layer tasked with extracting feature maps, a ReLU layer that functions as an activation function and substitutes negative values with zero, and finally, a max pooling layer of length 2 that reduces the size of the extracted feature maps by half by transmitting the maximum value of each pair of data. It should be noted that the stride size parameter for both the convolution and pooling layers is set to 1. Convolution operator can be considered as the core of a CNN. For an input vector \(\:X\), a one dimentional convolution filter \(\:K\) will produce its output \(\:Y\) as follows:

In the above equation, \(\:X\left(i\right)\) refers to the input vector as position \(\:i\), and \(\:K\left(m\right)\) is the kernek at position \(\:m\). In this equation, the sum operator is caried out on the kernel’s length. The ReLU activation operator returns the positive values of the received input \(\:z\) as folows:

The max pooling operator for reducing the length of obtained feature maps can be formulated as the following:

where \(\:Y\) refers to the received feature vector and \(\:s\) is the stride in the pooling layer. The feature maps extracted using the fully connected layers are converted into a vector form. Given that each training sample falls into one of the suitable or unsuitable categories, the last fully connected layer in the proposed CNN model comprises two weight values, each associated with one of the target categories. Ultimately, the posterior probabilities for the acceptance of the movie by the user are predicted using the SoftMax layer. In the method proposed, the posterior probabilities of the last CNN layer are utilized.

Ultimately, the CNN model derived from training the feature matrix of user U embodies the behavioral model of user U. In the second step of the proposed method, the importance of movie pages is computed based on the user’s browsing model and using the PageRank criterion, which is elaborated in the subsequent section.

Ranking movie pages based on pagerank criterion

In the method proposed, the features of the user’s navigation model on movie pages are utilized alongside the content features of the pages to offer recommendations. To model the user’s navigation pattern on web pages, the PageRank criterion is employed. In this scenario, the user’s browsing pattern on movie pages is depicted as a directed graph. Each node of this graph signifies one of the movie pages in the database, and each edge in this graph represents the user’s transition from one page to another. Furthermore, the direction of each edge in this graph indicates the direction of the user’s navigation. Based on this graph, the existing movie pages can be ranked according to their importance using the PageRank criterion.

The PageRank measure, initially presented by Page and Brin, operates under the assumption that a user explores the network guided by an invisible map (the transition matrix P). Occasionally, this user transitions to another node (page) with a chance of 1/n. This core idea, forms the foundation of the PageRank ranking system which is described as an n-dimensional vector48:

This relationship is repeated until the following condition is met48:

The initial value of vector v, representing the initial PageRank, is set to \(\:\frac{1}{\text{n}}\:\)for all nodes. The matrix e is a unit matrix, and β represents the probability of restart. The parameter \(\:\beta\:\) is set to 0.15, and the parameter \(\:\epsilon\:\) is set to \(\:{10}^{-3}\). The matrix P is defined as follows48:

A large PageRank value for a node signifies high centrality, making it a more suitable node for recommendation. However, due to the low diversity in the PageRank values across all nodes, identifying prominent nodes as the center poses a challenge. In this regard, an improved centrality criterion, termed PageRank-D, is introduced in49. This criterion, influenced by the distance between nodes, is defined as follows49:

In Eq. (8), d(i, j) represents the distance (Euclidean) between two nodes vi and vj. The distance of a vertice to others in the graph, can influence its PageRank value. In essence, nodes that are in closer proximity to a larger number of nodes possess a higher rank value. This suggests that these nodes hold greater importance for presentation as the output of the recommender system compared to other nodes. With this modification, the PageRank-D value associated with influential nodes diverges significantly from that of other nodes. The outcome of this phase of the proposed method is the importance vector of movie pages.

Providing recommendations

In the third phase of the proposed method, two probability vectors (derived from the CNN model) and importance (derived from the PageRank criterion) - are amalgamated to formulate the final ranking vector. This vector is computed as follows

In the aforementioned relation, \(\:Pro{b}_{svm}\left(i,j\right)\) represents the posterior probability, as estimated by the CNN model, for the acceptance of movie j by user i. Additionally, \(\:PR(i,j)\) signifies the PageRank-D criterion for the movie page j, based on the browsing graph of user i. In this relation, the parameter α denotes the impact factor of the user model in generating recommendations. This parameter lies within the range \(\:0\le\:\alpha\:\le\:1\). When \(\:\alpha\:>0.5\), the recommendation priority is based on the content similarity of movie pages with pages previously viewed. Conversely, if \(\:\alpha\:<0.5\), the recommendation prioritizes movies that have more connections with the movies previously viewed by the user. It’s worth noting that if \(\:\alpha\:=0\), the movie recommendation is solely based on the PageRank centrality criterion (the importance of the movie page). If \(\:\alpha\:=1\), the movie recommendation is solely based on the content similarity of movies and user features with pages previously viewed by similar users. Upon computation of the ranking vector in accordance with Eq. (9), the movies possessing the highest rank value in the aforementioned vector are ultimately recommended to the user, as the output of the proposed algorithm.

Implementation results

For experiments, we used MATLAB 2020a software. To evaluate the proposed method, we used the double cross validation technique. In this method, data is divided into two parts based on time characteristics. Data from primary time intervals are considered as training data for the model, and data from secondary time intervals are considered as test instances. The model is trained on the basis of the training instances and the graph structure is constructed. Finally, using the test data, we try to make predictions.

We compared our proposed technique to the methods of Sun et al.32, Yadav et al.33, Ez-Zahout et al.34, Ambikesh et al.35, and Zubi et al.36, based on precision and recall criteria. Based on the recommendations made by each model, the following metrics can be obtained:

-

TP (True Positive): the recommended items that actually belong to the user’s fatorive set.

-

FN (False Negative): The unrecommended items which belong to the user’s fatorive set.

-

FP (False Positive): The recommended items that donot belong to the user’s fatorive set.

Precision is a performance measure used to evaluate the proportion of accurate positive predictions. It assesses the correctness of the minority class by calcualting the ratio between correctly predicted positive samples and the total number of samples labeled as positive.

Recall is a metric that evaluates the proportion of accurate positive predictions out of all potential positive predictions. Recall encompasses the positive predictions that were not captured. Recall assesses how well the positive class was accounted for in this way. Utilizing recall is essential for evaluating the model’s performance comprehensively.

Figure 4 shows the investigation the effect of changes in parameter α on the metrics (a) precision and (b) recall. According to the conducted experiments, it has been determined that the parameter alpha can significantly impact the performance of the recommendation system. By adjusting the value of the alpha parameter, we can optimize the performance of the recommendation model. Based on the obtained results, using a value of 75% for alpha can yield the best precision and recall. When considering the value of 75% for alpha, precision reaches its maximum, and for values greater than 75%, recall continues to maintain its maximum value. This indicates that by adjusting this parameter, we can optimize the model’s performance. In all conducted experiments, the value of the alpha parameter has been set to 75%. It should be noted that this parameter value must be empirically determined based on the data type. Based on our data structure, it has been determined that this value is suitable, and it may be necessary to readjust this parameter for changes in the data.

In Fig. 5, we made changes to the number of recommendations and examined the precision value for this parameter. The precision value indicates the accuracy of the recommendations made by the system. As the number of recommendations increases, the likelihood of their accuracy decreases, leading to a descending trend in the precision graph. This is because the recommendation system prioritizes related recommendations as top priorities, thus increasing the likelihood of accuracy for recommendations in higher priority. As the number of recommendations increases, the likelihood of their acceptance decreases, resulting in a descending trend in the precision graph. However, through the combination of the two metrics we considered, our proposed method was able to increase the precision value.

Figure 6 depicts the changes of recall versus the number of recommendations. The recall value indicates how many of the user’s expected scenarios the recommendation system has successfully extracted. As it is evident, when the number of recommendations increases, the likelihood of extracting information from the user’s preferred dataset also increases; thus, increasing the number of recommendations leads to an enhancement in the recall metric. The results indicate that the presented approach is competitive in terms of the recall metric compared to the compared methods. Additionally, besides increasing the precision metric, it still maintains an acceptable level of recall.

In Figs. 7 and 8, we changed the number of users and examined the precision and recall metrics. In these experiments, it became evident that increasing the number of users leads to an increase in precision. The reason for this is that with an increased number of users, we obtain a more comprehensive dataset of user behavioral patterns, resulting in a more thorough training of our CNN model, consequently increasing the likelihood of more accurate recommendations. By increasing the number of users, the recall metric exhibits a descending trend. The reason for this decline is that when the number of users increases, the number of recommended items that are liked by users also significantly increases. As the number of recommendations remains constant with the increase in the number of users, the set of positive examples grows, but the model’s output for extracting True Positives remains constant, resulting in no actual increase. This doesn’t imply that the model’s performance deteriorated with the increase in the number of users. Instead, this decrease is due to the expansion of the positive set. Nevertheless, both graphs indicate that in addition to improving the precision metric, the model was able to maintain its suitable performance in terms of recall.

Figures 9 and 10 display a graph of changes in the precision and recall criteria for the number of movies. As the number of movies increases, we can create a more comprehensive model for recommendations. This is because the data is based on actual user observations, and with an increase in the number of movies, the likelihood of having more information from users’ past observations in these movies increases. Therefore, both precision and recall metrics increase simultaneously, and our proposed method has been able to perform better in both cases. This result demonstrates that our approach has been able to provide a more accurate system for recommendations in terms of modeling user behavior and preferences.

Table 3 summarizes the results obtained through the experiments. The proposed method delivers superior average precision results which exceed the second-best method by 0.72% and outperforms the worst-performing method by 2.42%. Our hybrid recommendation system proves effective at generating precise results based on the experimental results.

The proposed method maintains superior performance in average recall compared to other methods while showing a 3.35% improvement over the most inadequate method even though it falls behind the top-performing method by a slight margin. Our method demonstrates excellent competence in recall alongside robust precision capabilities.

The implementation of CNN along with PageRank as well as optimized parameter adjustments leads to better overall performance. The model benefits from detailed behavioral data in the dataset to better understand user preferences.

The research confirms hybrid recommendation framework capability to generate individualized and dependable recommendations when applied to real-life situations.

The system performance evaluation included testing computational times between the proposed model and baseline methods through experiments on equipment featuring an Intel Core i7 13,900 H CPU and 16 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU. The calculated times in Table 4 demonstrate the algorithmic complexity while working with 215 users and 508 movie pages.

A GPU-accelerated CNN used for our method needed 609 s (about 10 min) to complete training. The proposed method requires less time for execution than HHO or Apriori association rule mining which needed 1806 and 2417 s respectively. The GPU succeeded at executing CNN operations which led to an accelerated training process thus validating specific hardware makes deep learning algorithms more effective. Yadav et al.33 together with Ez-Zahout et al.34 reported the shortest training periods because their approaches had minimal complexity.

Our recommendation system delivered recommendations to users in an average time of 0.3 s during each session. The recommendation time of 0.3 s per user stands as a competitive result when compared to KNN based approaches that required 0.5 and 0.8 s per user according to Ez-Zahout et al.34 and Zubi et al.36. Through the integration of PageRank our solution achieved swift models of user behavior which produced these performance-oriented recommendations. The recommendation times reported by Yadav et al.33 and Ambikesh et al.35 were the fastest because clusters were pre-computed.

The proposed approach achieves optimal training performance and recommendation speed because it utilizes GPU acceleration for deep learning operations. This hybrid recommendation system proves its practicality for real-world recommendation systems because it demonstrates efficient training times alongside rapid recommendation speeds despite the HHO and Apriori methods requiring longer training times and KNN-based methods requiring slower recommendation speeds. The specific calculations about our dataset and hardware system demonstrate the computational efficiency of our proposed method.

Discussion

The proposed movie recommendation system generates experimental outcomes which receive an analysis in this section. The model evaluation utilized precision and recall metrics across different scenarios based on the number of recommendations together with user and movie variables. The research evaluated the performance changes of the model when varying the alpha parameter.

Analysis of experimental results

Our proposed approach displays its capacity for using user interaction patterns together with movie material to present precise individual recommendations in experimental results. The proposed technique outperformed existing methods from Sun et al.32 and Yadav et al.33 by building better precision (0.83%) and recall (0.62%). The precision rate of our method reached 0.823 when using 100 users and 500 movies while Sun et al.‘s method achieved 0.819 and Yadav et al.‘s method scored 0.821. The recall performance of our system at 0.9 stood on par with Sun et al.‘s result of 0.92 and outmatched Yadav et al.‘s outcome of 0.83.

Our model demonstrates outstanding performance in capturing user preferences because the observed enhancement proves its capability to deliver more precise recommendations. The alpha parameter displayed important effects on model performance because a value of 75% produced the best precision and recall results. The alpha parameter sets an equilibrium point between terming the CNN-based content matching scores and the PageRank browsing data evaluation. Our model achieved the optimal balance between content-based and collaborative filtering elements when set to 75% through this parameter. The CNN results receive higher weighting than PageRank results when the alpha value falls below 75% but PageRank results gain precedence when the alpha value surpasses 75%.

The evaluation demonstrated how precision dropped but recall improved as recommendation numbers increased because highly relevant items took priority during the recommendation process. In recommendation system operations this common trade-off exists because retrieving more items will typically result in lower precision levels. Research should investigate methods to achieve metric equilibrium by using adaptable threshold regulations or combining different ranking methods.

The precision metric improved when the user dataset expanded because the larger user behavioral patterns enabled better CNN model training. The number of users directly affected recall performance in an inverse relationship. The positive set grew larger but true positives failed to match this expansion. The growth of user base corresponds directly to an increase in the number of liked recommended items. The model maintains a static output for extracting True Positives even though the positive example set grows due to the constant number of recommendations in relation to user growth.

The number of movies added to the system directly led to higher precision and recall values. The bigger the size of the movie dataset becomes the more authenticated models can construct user preference patterns thus enhancing recommendation quality. The CNN successfully analyzed movie semantics while PageRank generated strong user browsing data which produced an enhanced user preference model.

Our hybrid approach proves effective according to the analysis performed by Sun et al.32 and Yadav et al.33. The modest percentage improvements in precision and recall result in substantial advancements of recommendation quality in practical applications because small enhancements deliver substantial user satisfaction and engagement results.

The research results deliver important practical value to both online platforms and entertainment industry operations. The proposed recommendation method delivers enhanced user satisfaction and improved engagement through its ability to provide highly pertinent movie suggestions. The system generates higher revenue through its operation. The methodology proves adaptable to suggest various forms of content beyond movies including music and books as well as products.

Limitations and future work

Numerous restrictions exist in this research which creates potential research opportunities for the future.

-

Data limitations: The main constraint stems from working with only one dataset. The dataset contains complete behavioral user information about page interactions and time spent on movie pages that standard publicly-available datasets do not provide. The special behavioral information present in this data set reveals hidden user preference data that rating systems cannot detect. The dataset maintains its validity because of its distinct attributes yet we realize the model needs to be tested on extensive diverse datasets that have more than 10,000 records. Future research will analyze the proposed model by testing it against different datasets for evaluation of scalability and performance among various data distributions. The dataset contains restricted user and movie participation which might not reflect actual real-life situations. The analysis needs future datasets that contain both extensive user demographic information and varied genres of films.

-

Methodological Limitations: The study failed to evaluate how different deep learning architectures as well as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) along with attention mechanisms influence model performance. Future research will analyze these modern architectural approaches because they may boost recommendation system performance. Also, the model’s ability to provide real-time, context-aware recommendations was not investigated. Future works will consider how to incorporate real-time user feedback and contextual information to enhance the systems usability. Additionally, the system offered restricted features to its users. Recommendation accuracy can be enhanced through the addition of demographic along with social information into the user feature set. Further research aims to discover integration designs for these proposed features.

Conclusion

The paper’s findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed movie recommendation system, which integrates text mining and machine learning techniques. By incorporating user profile features and movie attractiveness, the system adeptly aligns with users’ preferences and behavioral history. Leveraging PageRank criteria and a CNN model enables the system to generate tailored recommendations and accurately predict movie acceptance. The system’s superior precision in recommendations, compared to alternative methods, underscores its potential to elevate the recommendation experience for users across online platforms and e-commerce applications. These results affirm the system’s capability to leverage advanced techniques in effectively addressing the challenges of providing personalized movie recommendations and its potential to significantly enhance user satisfaction and engagement in various online settings.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Isinkaye, F. O., Folajimi, Y. O. & Ojokoh, B. A. Recommendation systems: principles, methods and evaluation. Egypt. Inf. J. 16 (3), 261–273 (2015).

Nilashi, M. et al. A new method for collaborative filtering recommender systems: the case of Yahoo! Movies and tripadvisor datasets. J. Soft Comput. Decis. Support Syst., 3(5). (2016).

Smith, B. & Linden, G. Two decades of recommender systems at Amazon. Com. IEEE Internet Comput. 21 (3), 12–18 (2017).

Greenstein-Messica, A. & Rokach, L. Personal price aware multi-seller recommender system: evidence from eBay. Knowl. Based Syst. 150, 14–26 (2018).

Itmazi, J. A. & Megías, M. G. Using recommendation systems in course management systems to recommend learning objects. Int. Arab. J. Inf. Technol. 5 (3), 234–240 (2008).

Kumar, M., Yadav, D. K., Singh, A. & Gupta, V. K. A movie recommender system: Movrec. Int. J. Comput. Appl., 124(3). (2015).

Ji, K. & Shen, H. Jointly modeling content, social network and ratings for explainable and cold-start recommendation. Neurocomputing 218, 1–12 (2016).

Zhao, W. X. et al. Connecting social media to e-commerce: Cold-start product recommendation using microblogging information. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 28 (5), 1147–1159 (2015).

Son, L. H. Dealing with the new user cold-start problem in recommender systems: A comparative review. Inform. Syst. 58, 87–104 (2016).

Da Silva, E. Q., Camilo-Junior, C. G., Pascoal, L. M. L. & Rosa, T. C. An evolutionary approach for combining results of recommender systems techniques based on collaborative filtering. Expert Syst. Appl. 53, 204–218 (2016).

Zhou, Q. Supervised approach for detecting average over popular items attack in collaborative recommender systems. IET Inf. Secur. 10 (3), 134–141 (2016).

Yang, Z., Xu, L., Cai, Z. & Xu, Z. Re-scale adaboost for attack detection in collaborative filtering recommender systems. Knowl. Based Syst. 100, 74–88 (2016).

Liang, X., Xia, Z., Pang, L., Zhang, L. & Zhang, H. Measure prediction capability of data for collaborative filtering. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 49, 975–1004 (2016).

Hernando, A., Bobadilla, J. & Ortega, F. A Non negative matrix factorization for collaborative filtering recommender systems based on a bayesian probabilistic model. Knowl. Based Syst. 97, 188–202 (2016).

Xu, Y. & Yin, J. Collaborative recommendation with user generated content. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 45, 281–294 (2015).

Puglisi, S., Parra-Arnau, J., Forné, J. & Rebollo-Monedero, D. On content-based recommendation and user privacy in social-tagging systems. Comput. Stand. Interfaces. 41, 17–27 (2015).

Zhao, W. X. et al. Exploring demographic information in social media for product recommendation. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 49, 61–89 (2016).

Katarya, R. & Verma, O. P. Restaurant recommender system based on psychographic and demographic factors in mobile environment. In 2015 International Conference on Green Computing and Internet of Things (ICGCIoT) (pp. 907–912). IEEE. (2015).

Al-Shamri, M. Y. H. User profiling approaches for demographic recommender systems. Knowl. Based Syst. 100, 175–187 (2016).

Moradi, P. & Gholampour, M. A hybrid particle swarm optimization for feature subset selection by integrating a novel local search strategy. Appl. Soft Comput. 43, 117–130 (2016).

Capdevila, J., Arias, M. & Arratia, A. GeoSRS: A hybrid social recommender system for geolocated data. Inform. Syst. 57, 111–128 (2016).

Pessemier, T. D., Dhondt, J. & Martens, L. Hybrid group recommendations for a travel service. Multimedia Tools Appl. 76, 2787–2811 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Online video recommendation in sharing community. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (pp. 1645–1656). (2015).

Ahuja, R., Solanki, A. & Nayyar, A. Movie recommender system using k-means clustering and k-nearest neighbor. In 2019 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence) (pp. 263–268). IEEE. (2019).

Katarya, R. & Verma, O. P. An effective collaborative movie recommender system with cuckoo search. Egypt. Inf. J. 18 (2), 105–112 (2017).

Thakker, U., Patel, R. & Shah, M. A comprehensive analysis on movie recommendation system employing collaborative filtering. Multimedia Tools Appl. 80 (19), 28647–28672 (2021).

Gupta, M., Thakkar, A., Gupta, V. & Rathore, D. P. S. Movie recommender system using collaborative filtering. In 2020 international conference on electronics and sustainable communication systems (ICESC) (pp. 415–420). IEEE. (2020).

Airen, S. & Agrawal, J. Movie recommender system using k-nearest neighbors variants. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 45 (1), 75–82 (2022).

Chauhan, A., Nagar, D. & Chaudhary, P. Movie recommender system using sentiment analysis. In 2021 International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM) (pp. 190–193). IEEE. (2021).

Tahmasebi, H., Ravanmehr, R. & Mohamadrezaei, R. Social movie recommender system based on deep autoencoder network using Twitter data. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 1607–1623 (2021).

Lee, C., Han, D., Han, K. & Yi, M. Improving graph-based movie recommender system using cinematic experience. Appl. Sci. 12 (3), 1493 (2022).

Sun, L., Wang, X., Wang, Z., Zhao, H. & Zhu, W. Social-aware video recommendation for online social groups. IEEE Trans. Multimedia. 19 (3), 609–618 (2016).

Yadav, V., Shukla, R., Tripathi, A. & Maurya, A. A new approach for movie recommender system using K-means clustering and PCA. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 80 (02), 159–165 (2021).

Ez-Zahout, A., Gueddah, H., Nasry, A., Madani, R. & Omary, F. A hybrid big data movies recommendation model based Knearest neighbors and matrix factorization. Indonesian J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 26 (1), 434–441 (2022).

Ambikesh, G., Rao, S. S. & Chandrasekaran, K. Application of machine learning in movie recommendation using Harris Hawks optimization and K-means (HHO-k-means) clustering. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 11 (7s), 515–525 (2023).

Zubi, Z. S., Elrowayati, A. A. & Fanas, I. S. A. A movie recommendation system design using association rules mining and classification techniques. WSEAS Trans. Computers. 20, 189–199 (2022).

Jain, S. & Essah, R. Movie recommendation using collaborative filtering to make accurate predictions. In 2022 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Materials (ICACCM) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. (2022).

Sharma, B. et al. Hybrid sparrow clustered (HSC) algorithm for top-N recommendation system. Symmetry 14 (4), 793 (2022).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Deep GraphSAGE-based recommendation system: jumping knowledge connections with ordinal aggregation network. Neural Comput. Appl. 34 (14), 11679–11690 (2022).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Collaborative filtering: comparative study between matrix factorization and neural network method. In Networked Systems: 8th International Conference, NETYS 2020, Marrakech, Morocco, June 3–5, 2020, Proceedings 8 (pp. 361–367). Springer International Publishing. (2021).

Rendle, S., Krichene, W., Zhang, L. & Anderson, J. Neural collaborative filtering vs. matrix factorization revisited. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (pp. 240–248). (2020).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Overview of the main recommendation approaches for the scientific articles. In International Conference on Business Intelligence (pp. 107–118). Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2021).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Contextual Recommendations: Dynamic Graph Attention Networks with Edge Adaptation (IEEE Access, 2024).

Ziaee, S. S., Rahmani, H. & Nazari, M. MoRGH: movie recommender system using GNNs on heterogeneous graphs. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 66 (12), 7419–7435 (2024).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Social recommendation system based on heterogeneous graph attention networks. Int. J. Data Sci. Analytics, 1–17. (2024).

El Alaoui, D. et al. Comparative study of filtering methods for scientific research Article recommendations. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 8 (12), 190 (2024).

Kim, S. W. & Gil, J. M. Research paper classification systems based on TF-IDF and LDA schemes. Human-centric Comput. Inform. Sci. 9, 1–21 (2019).

Page, L., Brin, S., Motwani, R. & Winograd, T. The pagerank citation ranking: Bring order to the web. Technical report, stanford University. (1998).

Li, Y., Jia, C. & Yu, J. A parameter-free community detection method based on centrality and dispersion of nodes in complex networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 438, 321–334 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study did not involve human subjects research as defined by Belmont Report.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Zheng, H. & Cui, H. User preference modeling for movie recommendations based on deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 16592 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00030-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00030-5