Abstract

In order to study the Anti-Penetration Randomness of Metal Protective Structures (APRMPS) for the penetration probabilities of Metal Protective Structures under the action of the basic random variables, this paper analyzes the candidates for the basic random variables and the random response of APRMPS, and, on the basis of the improvement of Genetic Algorithm, proposes Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm, including its main processes of the optimization of Back Propagation Neural Network. And by adopting the Back Propagation Neural Network optimized by Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm (DLGABPNN) as the surrogate model of APRMPS, this paper presents the technical route of DLGABPNN-MCS, the Monte Carlo Simulation with DLGABPNN calculation as repeated sampling tests, to addressing APRMPS. Finally, with two applied examples of the anti-penetration randomness of metal targets, this paper demonstrates the application procedures for this method, proves the higher efficiency of Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm than Genetic Algorithm in optimizing Back Propagation Neural Network and verifies the effectiveness of DLGABPNN-MCS in studying APRMPS. This paper may have some significance in proposing Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm—the new, universal heuristic algorithm, and providing the common technical method for the APRMPS study based on DLGABPNN-MCS, in the hope of promoting the application of Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm in other optimization problems, and offering reference for the further study of APRMPS or the study of other random problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The anti-penetration of protective structures is a typical transient high-strain problem. Since any slight change in conditions will lead to those in the penetration results of protective structures, in the anti-penetration tests of protective structures, random results will occur as for whether the protective structures at the penetration limit state can be penetrated by the fragments. This explains why some researches labeled the ballistic limit velocity as V501,2,3,4, indicating that the fragments, at the ballistic limit velocity, will penetrate the protective structures with a 50% probability. Although it has been repeatedly found that there is uncertainty in the mechanical behavior of the anti-penetration of protective structures, the anti-penetration of protective structures has been taken as a deterministic one, leading to the ignorance about the mechanical behavior uncertainty of the anti-penetration of protective structures. Under this circumstance, it is necessary to perceive the anti-penetration of protective structures as a randomness problem, and to make a stochastic analysis of the randomness of the mechanical behavior of the anti-penetration of protective structures, so as to obtain the penetration probabilities of protective structures under the action of basic random variables.

What should also be noted is that machine learning has found extensive use in engineering. Khatir et al.5 employed Firefly Algorith and Genetic Algorithm (GA) to optimize the coordinate modal assurance criterion for complex structures, so as to identify multiple local damages in complex structures. Khatir et al.6 used Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm (PSO) and GA in optimizing the gradient boosting for strain prediction in near-surface mounted of fiber-reinforced polymer strengthened reinforced concrete beam, thus achieving the accurate result of strain prediction. Khatir et al.7 even applied the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) optimized by Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm in predicting multiple damages represented by holes in the aluminum plate, and found that the ANNs optimized in this way demonstrated superior performance in damage forecasting. Also, Khatir et al.8 constructed the hybrid ANN-RSA model by optimizing ANN with Reptile Search Algorithm (RSA) for structural damage detection in steel beams, finding that “the integration of RSA into ANN training significantly improves the accuracy and computational efficiency of damage prediction in structural health monitoring.” Besides, Khatir et al.9 proposed a new hybrid algorithm by integrating PSO into YUKI, and further combined the PSO-YUKI algorithm with radial basis functions for double cracks identification in carbon fiber reinforced polymer cantilever beams. Their results show that the PSO-YUKI algorithm shows robustness in double cracks depth identification. And Khatir et al.10 proposed another hybrid model, the BOA-ANN algorithm optimizing ANN with Butterfly Optimization Algorithm (BOA), applied this model in identifying the crack depth in steel beam structures, and found that BOA-ANN can predict crack depth with improved accuracy. Furthermore, Achouri et al.11 proposed a novel hybrid swarm optimization algorithm by combining PSO and BOA for the ANN optimization, adopted PSO-BOA-ANN for structural damage prediction, and found that PSO-BOA-ANN exhibits robust capability in structural damage detection.

The studies above show that machine learning can deliver remarkable benefits in solving complex engineering problems such as structural damage detection. Therefore, this paper also take advantage of machine learning to study the Anti-Penetration Randomness of Metal Protective Structures (APRMPS). And Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) based on the error back propagation algorithm is a well-recognized ANN with remarkably strong nonlinear mapping ability, and currently among the most widely used ANNs12,12,14. Nevertheless, the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN exert a significant impact on the training effects of the network, so if these parameters are not properly set, the training effects will be worse—a disadvantage of BPNN. On the other hand, GA is characterized by its strong global optimization ability, so it is effective to offset BPNN’s disadvantage by adopting GA to optimize the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN. In fact, GA is often used as an optimization algorithm for BPNN15,16,17,18. What should be noted is that this optimization method is facing a challenge: the adoption of the selection operator for each generation of individuals in the population suggests too much human intervention in the process of population evolution, resulting in a low population evolution rate and thus reducing the efficiency of GA to optimize the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN. In order to address this challenge, this paper, based on the improvement of GA, proposes a new algorithm, Dynamic Lifecycle Genetic Algorithm (DLGA), which cancels the selection operation of GA and accordingly provides a life cycle for each individual in the population. Each individual automatically follows its development and reproduction within its own life cycle, so as to realize the natural evolution of the population, reducing the human intervention in the process of population evolution and enhancing the efficiency of optimizing the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN. Therefore, this paper investigates APRMPS by taking BPNN optimized by DLGA (DLGABPNN) as the surrogate model and adopting DLGABPNN-MCS, the Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) with DLGABPNN calculation as repeated sampling tests.

In a nutshell, in exploring APRMPS by the method of DLGABPNN-MCS for the penetration probabilities of metal protective structures under the action of basic random variables, Section “APRMPS analysis” will analyze the possible candidates for basic random variables and random responses of APRMPS; Section “APRMPS study based on DLGABPNN-MCS” will propose DLGA, an improved version of GA, including its main processes of the optimization of BPNN, and the technical route of DLGABPNN-MCS to addressing APRMPS; Section “Applied examples”, taking the anti-penetration randomness of two metal targets as an example, attempts to prove the higher efficiency of DLGA than GA in optimizing BPNN and verify the effectiveness of DLGABPNN-MCS in studying APRMPS. This paper hopes to promote the application of DLGA in other optimization problems and to provide reference for further study on APRMPS and study on other randomness problems.

APRMPS analysis

Basic random variables of APRMPS

In the numerical simulation of explosion and shock dynamics, for common metal materials, the principal stress is generally calculated by the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state19; the deviatoric stress by the Johnson–Cook plasticity model19,20,21; the damage degree by the Johnson–Cook failure model21.

The Mie-Grüneisen equation of state19 has two two expressions—the compression equation of state and the expansion equation of state

where p is the principal stress, \(\mu = \frac{\rho }{{\rho_{0} }} - 1\) is the compression degree, with \(\rho_{0}\) being the initial density and \(\rho\) the current density, c0 is the sound velocity when p = 0, E is the energy in per unit volume, \(\gamma_{0}\) is the Grüneisen coefficient when p = 0, and a, S1, S2 and S3 are material parameters.

In the Johnson–Cook plasticity model19,20,21, the equation for the Von Mises flow stress \(\sigma_{y}\) is

where \(\varepsilon_{p}\) is the equivalent plastic strain, \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{p}^{ * } = \frac{{\dot{\varepsilon }_{p} }}{{\dot{\varepsilon }_{0} }}\) is the dimensionless equivalent plastic strain rate, \(T^{ * } = \frac{{T - T_{r} }}{{T_{m} - T_{r} }}\) is the dimensionless homologous temperature, with T being the current temperature, Tr the room temperature and Tm the melting temperature, and A, B, C, n and m are material parameters.

In the Johnson–Cook failure model21, the equation for the failure strain \(\varepsilon^{f}\) is

where \(\sigma^{ * } = p/\overline{\sigma }\) is the stress triaxiality, with \(\overline{\sigma }\) being the equivalent stress, and D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5 are material parameters.

From Eq. 1 to Eq. 3, \(\gamma_{0}\), a, S1, S2 and S3 in the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, A, B, C, n and m in the Johnson–Cook plasticity model, and D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5 in the Johnson–Cook failure model are material parameters. Jiang et al.22 pointed out that even for the same material, the parameters given by different researchers may vary: for instance, Holmquist et al.23 gave a different parameter value for the Johnson–Cook failure model of 4340 steel from the version proposed by Quan et al.24, and Holmquist et al.23 also gave a different parameter value for the Johnson–Cook plasticity model of 6061-t6 aluminum alloy from the version of Liu et al.25. Cullis et al.26 and Normandia et al.27 presented different parameter values for the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state of RHA steel. There are numerous examples for this, which shows that there is uncertainty in the determination of the parameter values for the performance equation of metal materials, leading to the uncertainty of the properties of the materials described by these parameters. What’s more, in the study on the stochastic dynamics of metal structures under explosion load, Chen et al.19,28 argued that each parameter for the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model are random, leading to the randomness of the principal stress, deviatoric stress and damage degree of metal structures under explosion load.

Moreover, errors in metal smelting and changes in environmental temperature will also cause changes in the density of metal materials, thus leading to the randomness of the metal material density. In the anti-penetration tests of metal protective structures, under the influence of the charge errors of the fragment launcher and the errors of the fragment velocity recording device, the penetration velocity of the fragment recorded in each test is also random.

Thus, in the study on APRMPS, since the randomness of the density and the performance equation parameters above of the materials of metal protective structures and fragments, and the randomness of the penetration velocity of fragments, may exert impacts on the penetration performance of fragments and the anti-penetration performance of metal protective structures, it is necessary to select from these parameters the ones that have a significant effect on the penetration results of metal protective structures as basic random variables.

Random response of APRMPS

In studying APRMPS, in order for ANN to identify the penetration results of metal protective structures under various randomness conditions, this paper introduces the penetration-recognizing coefficient δ to determine whether metal protective structures are penetrated under the action of basic random variables: if metal protective structures are penetrated, δ will be recognized to be 1; if not, δ will be recognized to be 0. This means that the randomness of the penetration of metal protective structures under basic random variables can be expressed by that of the 0–1 recognition results of δ. In this case, this paper defines δ as the random response of APRMPS, and considers APRMPS the problem of estimating the penetration probabilities of metal protective structures under basic random variables on the basis of the statistical analysis results of δ.

APRMPS study based on DLGABPNN-MCS

DLGA

-

(1)

Life expectancy function and reproductive chromosome quantity function of individuals

In DLGA, an individual’s life expectancy refers to the upper limit of its life. Being not a fixed value, the life expectancy needs to be continuously updated in iterative calculations. An individual’s reproductive chromosomes refer to the chromosomes for the generation of new individuals through crossover operations and mutation operations. Being exactly the same as its own chromosome, the reproductive chromosomes can be generated by directly copying the latter. However, the quantity of an individual’s reproductive chromosomes in each iteration is not a fixed neither. Therefore, this paper proposes the life expectancy function shown in Eq. 4 and the reproductive chromosome quantity function in Eq. 5 to determine in each iteration the number of life expectancy and reproductive chromosomes of each living individual in the population.

where Lij is the life expectancy of the individual i in the jth iteration calculation, Fi is the fitness of the individual i, nj is the quantity of living individuals in the jth iteration calculation (i.e. excluding the unborn and dead individuals in the jth iteration calculation), NL is upper limit quantity of living individuals, and C1 is the coefficient of the equation.

where Qij is the quantity of the reproductive chromosomes generated by the individual i in the jth iteration calculation, Aij is the age of the individual i in the jth iteration calculation, C2 is the coefficient of the equation, and the other parameters are the same as those in Eq. 4.

-

(2)

Crossover operator and mutation operator

The crossover operator and the mutation operator of DLGA are the same as those of GA. Thus in the real number coding mode, any two reproductive chromosomes can cross based on the specified crossover probability PC, and the crossover operator can be expressed by Eq. 6:

where x1 and x2 are respectively the genes crossed in any two reproductive chromosomes, \(x^{\prime}_{1}\) and \(x^{\prime}_{2}\) are respectively the newly-formed genes in these two reproductive chromosomes, and a, a random number within the interval [0, 1], represents the numeric exchange ratio of the gene x1 to the gene x2 in this crossover.

In the real number coding mode, each reproductive chromosome can mutate with the specified mutation probability PM, and the mutation operator can be expressed by Eq. 7:

where x is the mutant gene in an reproductive chromosome,\(x^{\prime}\) is the new gene generated after x mutated, xmax and xmin are respectively the upper limit and the lower limit to which x mutates, and r1 is a random number within the interval [0, 1], which determines the mutation mode of x in this process—from Eq. 7 inferred two mutation modes. As shown in Eq. 8, f(Nj) is a function with a range of [0, 1), which can guarantee that the variation of x in this mutation won’t be excessively wide.

where Nj is the total quantity of having-been-born individuals while reaching the jth iteration calculation (the total quantity of the living and dead individuals while reaching the jth iteration calculation), NB is the upper limit quantity of having-been-born individuals, and r2 is a random number within the interval [0, 1], which can effectively reduce the value of the function f(g).

-

(3)

Life cycle of individuals

The life cycle of an individual can be so defined: before its birth, an individual’s age is 0; after its birth, its initial age is 1, and its age is increased by 1 in each iteration calculation. Meanwhile, in each iteration calculation, an individual’s life expectancy is calculated according to Eq. 4 and the quantity of its reproductive chromosomes is calculated according to Eq. 5, on which the replication of the individual’s chromosome is based to become the reproductive chromosomes. The reproductive chromosomes will participate in the crossover operations and mutation operations to form new individuals. Once the individual’s age reaches the life expectancy in an iterative calculation, the individual will die, which means that after that, the individual will no longer participate in the iterative calculation, that its age and life expectancy will no longer be updated, and that the individual will no longer generate reproductive chromosomes either.

-

(4)

End conditions of DLGA

The 4 end conditions of DLGA in the jth iteration calculation are as follows:

-

Condition 1: No better individual appears in Tend consecutive iteration calculations, where Tend is the iterative calculation termination threshold that needs to be set artificially.

-

Condition 2: nj drops to 0.

-

Condition 3: nj reaches NL.

-

Condition 4: Nj reaches NB.

-

(5)

Running process of DLGA

DLGA runs through the following process:

Step 1: Determine the fitness function. An individual’s fitness function is determined by the practical situation and specific requirements of the optimization problem.

Step 2: Set parameters. Basic parameters should be set: ① n1, the quantity of the first-generation individuals, ② NL, ③ NB, ④ Tend, ⑤ C1, the coefficient of life expectancy function, ⑥ C2, the coefficient of reproductive chromosome quantity function, ⑦ PC, the crossover probabilities of reproductive chromosomes, and ⑧ PM, the mutation probabilities of reproductive chromosomes.

Step 3: Generate first-generation individuals. The first-generation individuals of the population are generated in the same way as GA; the chromosome of each first-generation individual is encoded and the initial age of each first-generation individual is 1.

Step 4: Calculate each first-generation individual’s fitness. The fitness function is applied to calculate each first-generation individual’s fitness.

Step 5: Calculate the individuals’ life expectancy. The life expectancy of each individual in the current iterative calculation is calculated according to Eq. 4.

Step 6: Form the population. Each individual’s age and life expectancy are taken into account to determine whether they can continue to survive: If its age does not reach the life expectancy, the individual continues to survive; If its age has reached the life expectancy, it dies, and from then on, the iterative calculation will be terminated. Then, the individuals that continue to survive are aggregated into a population. The quantity of the living individuals and those of individuals in the previous generations in the population are counted.

Step 7: Generate reproductive chromosomes by individuals. The quantity of reproductive chromosomes to be generated by each living individual in each iteration is calculated according to Eq. 5, on which the replication of the individual’s chromosome is based to become reproductive chromosomes.

Step 8: Update each individual’s age. Each living individual’s age is increased by 1.

Step 9: Generate new individuals. The crossover operations and mutation operations are performed on the reproductive chromosomes in the current iterative calculation in turn to generate new individuals, whose initial age is 1.

Step 10: Calculate new individuals’ fitness. The fitness function is applied again to calculate each new individual’s fitness.

Step 11: Determine whether the optimal individual is updated. If the fitness of each new individual is not higher than that of the current optimal individual, the optimal individual is not updated, and tend, the number of consecutive iterations without better individuals, is increased by 1; otherwise, the new individual with the highest fitness is taken as the optimal, and tend is reduced to 0.

Step 12: Determine whether the iteration calculation should continue. If none of the 4 end conditions of iteration calculation is met, optimization has not yet been completed, and Step 5-Step 12 should be repeated. If Condition 1 is met, or tend = Tend, the global optimal point has successfully been searched and the iteration calculation will be terminated. If any of the other 3 conditions is met, the optimization fails, and it should return to Step 1 to start another round of optimization.

From the above fundamental principle of DLGA, it can be found that the essential difference between DLGA and GA lies in this fact: without the selection operation in GA, DLGA introduces parameters like an individual’s age, life expectancy and reproductive chromosomes. An individual produces reproductive chromosomes during its survival, and once its age reaches life expectancy, it will die, thus forming its life cycle. Through the crossover operation and mutation operation in GA, each reproductive chromosome will develop a new individual, which starts its own life cycle. In this way, each individual in the population can automatically complete the replacement of the old with the new in its own life cycle, hence the natural evolution of the population. In short, DLGA can reduce human intervention in the process of population evolution, thereby enhancing the population evolution speed.

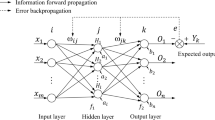

BPNN

BPNN is a typical multi-layer forward artificial neural network, and the following takes single-hidden-layer BPNN as an example to give a brief introduction to the principles of BPNN training29.

The training of BPNN includes input information forward-propagation and error information back-propagation, and the process of the input information forward-propagation can be illustrated as follows:

It is assumed that the neuron quantities of the input layer, hidden layer and output layer of the BPNN are respectively n, m and l. Then, with the input of the training sample information into the BPNN, the output values of the neurons in the hidden layer and output layer of the BPNN can be respectively calculated by Eq. 9 and Eq. 10:

where vij and wjk are the weights of neurons, αj and βk are the thresholds of neurons, xi is the input information, and yj and ok are respectively the output values of the neurons in the hidden layer and output layer. And the function f(net) is the activation function of neuron. If the f(net) is a bipolar Sigmoid function, it can be expressed by Eq. 11:

The process of the error information back-propagation can be demonstrated as follows:

Firstly, the current iteration error information is calculated according to Eq. 12:

where E is error information, dk is the expected output value of each neuron in the output layer. Then, the corrected values of the weight and threshold of each neuron in the BPNN can be respectively calculated by Eq. 13–Eq. 16:

where η is network training rate.

BPNN optimized by DLGA

Similar to the optimization of BPNN by GA15,16,17,18, the optimization of BPNN by DLGA in this paper refers to the optimization of the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN by applying DLGA. Since each new individual generated by DLGA will give BPNN a complete set of initial weights and thresholds, and call BPNN for a complete training and testing process, the population evolution of DLGA is the optimization of the initial weights and thresholds of BPNN. When the genetic calculation is completed, the initial weights and thresholds corresponding to the optimal individuals are those of BPNN optimization, and the trained and tested BPNN corresponding to the optimal individuals is the optimized BPNN (DLGABPNN). The main process of the optimization of BPNN by DLGA is presented in Fig. 1 in the following.

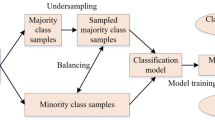

APRMPS study based on DLGABPNN-MCS

DLGABPNN-MCS in this paper refers to the MCS that takes the DLGABPNN calculation as repeated sampling tests. The process of the APRMPS study based on DLGABPNN-MCS is presented in the following.

-

(1)

Constructing DLGABPNN

First, the parameters that can exert a significant effect on the penetration results of metal protective structures are selected from the ones discussed in Section “Basic random variables of APRMPS” as basic random variables, and δ is taken as random response. After this, the sample points of the basic random variables are extracted and called in turn to perform repeated numerical simulations on APRMPS, so as to obtain the 0–1 recognition result of δ corresponding to each sample point. With the data being standardized, the standardized sample points of the basic random variables are used as the input data, and the 0–1 recognition results of δ are taken as the expected output data, thereby constructing the training sample sets and the test sample sets of DLGABPNN. Then, with the two types of sample sets, BPNN is optimized by applying DLGA, from which the optimal BPNN, or DLGABPNN, is developed for the APRMPS study.

-

(2)

Applying DLGABPNN-MCS in APRMPS study

Firstly, the sample points are randomly selected based on the statistical distribution of basic random variables and are standardized to construct the prediction sample sets of APRMPS, which are later used for DLGABPNN-MCS, so as to quickly find the 0–1 recognition results of δ corresponding to the prediction sample sets. Finally, the 0–1 recognition results of δ are statistically analyzed to obtain the estimates of the penetration probabilities of metal protective structures.

The technical route shown in Fig. 2 summarizes the operation process of the APRMPS study with LCABPNN-MCS.

Applied examples

Example 1

This example adopted the anti-penetration tests of the metal targets reported in Reference 20, in which the targets were 12 mm-thick plane steel plates, and the fragments were tungsten alloy cubes of a size of \(7.5{\kern 1pt} \;{\text{mm}} \times 7.5\;{\text{mm}} \times 7.5\;{\text{mm}}\), with the measured result of V50 = 821 m/s and shear plugging.

Numerical model

In the repeated numerical simulations of the randomness study, this example took the generalized interpolation material point method (GIMPM)30 for its numerical calculation, and applied a numerical calculation program based on a self-complied GIMPM program in the Fortran language, to which a self-developed material point free outflow boundary condition31 was added, so that the fragments and the plugs could freely go beyond the background grid boundaries. In this way, a numerical model was constructed as shown in Fig. 3, and Tables 1, 2 and 3 show the deterministic parameter values for the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model of the steel and the tungsten alloy, with a density of 7.85 g/cm3 and 17.3 g/cm3 respectively.

For the accuracy of the basic random variables selected by the repeated numerical simulations of the GIMPM program, and that of the training sample set and the test sample sets of ANNs constructed in the same procedures, it is necessary to verify the accuracy of the GIMPM program to simulate the test results of this example in advance. Thus, the penetration velocity of the fragments was set at \(V = V_{50} \pm 10\) m/s (i.e. 811 m/s and 831 m/s) and the numerical simulation results by the GIMPM program are shown in Fig. 4.

According to Fig. 4, when V = 811 m/s, the fragment failed to penetrate the target and was embedded in it, leaving a large depression of the target; when V = 831 m/s, the fragment successfully penetrated the target and caused shear plugging. These simulation results are entirely consistent with the test results20. Therefore, the GIMPM program is capable of conducting accurate numerical simulations of this example, thus ensuring that the basic random variables selected, and the training sample set and the test sample sets of ANNs are accurate, meeting the demand from the APRMPS study.

Selection of basic random variables

In order to make clear the parameters discussed in Section “Basic random variables of APRMPS”, the APRMPS study labeled the density of, and the parameters in the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model of the fragment material (tungsten alloy) respectively as \(\rho_{{F{0}}}\), \(\gamma_{F0}\), aF, SF1, SF2, SF3, AF, BF, CF, nF, mF, DF1, DF2, DF3, DF4 and DF5, and labeled the density of, and the parameters in the three equations/models of the target material (steel) respectively as \(\rho_{{T{0}}}\), \(\gamma_{T0}\), aT, ST1, ST2, ST3, AT, BT, CT, nT, mT, DT1, DT2, DT3, DT4 and DT5. In order to reveal the common and universal aspects of the APRMPS study, it was assumed that the 33 parameters were all independent of each other and subject to the normal distribution. By changing the values of these 33 parameters one by one and repeating the numerical simulation shown in section “Numerical model”, it was found that changing the values of the parameters V, \(\rho_{{F{0}}}\), AF, \(\rho_{{T{0}}}\), \(\gamma_{T0}\), AT, BT, CT, nT, DT1 and DT2 could change the numerical simulation results. That is, when changing the values of these 11 parameters, it can lead the targets to be penetrated under the mean \(\overline{V}\) of V is 811 m/s, and not be penetrated under \(\overline{V}\) is 831 m/s. Thus it is justified to believe that these 11 parameters exert a significant influence on the penetration results of the targets in this study, and to take these 11 parameters as the basic random variables of the APRMPS in this example.

APRMPS study

In order to reveal the common and universal aspects of the APRMPS study, it was assumed that the 11 basic random variables were all independent of each other and subject to the normal distribution, so the means of these basic random variables were their deterministic parameter values as shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Then, DLGABPNN-MCS was adopted to study APRMPS under the 4 randomness conditions that the values of the coefficients of variation (CVs) of these basic random variables were respectively 0.01, 0.03, 0.05 and 0.07. Additionally, in the ANN training and testing phases of this example, BPNN and the BPNN optimized by GA (GABPNN) worked as the performance comparison objects of DLGABPNN in order to explore the advantages of DLGABPNN as a surrogate model for numerical models.

-

(1)

Constructing the training sample set and the test sample set

For the generalization capabilities of DLGABPNN, GABPNN and BPNN, under the randomness conditions that the CVs of basic random variables were all 0.1 and that \(\overline{V}\) = V50 (821 m/s), 2000 sample points were selected by applying the Latin Hypercube Sampling, and then underwent the repeated numerical simulations based on the GIMPM program discussed in Section “Numerical model” to obtain the 0–1 recognition results of δ corresponding to these sample points, so as to construct a 2000-point training sample set for training the 3 ANNs. Further, in the interval of \(V_{50} \pm 100\) m/s, being gradually increased by 10 m/s each time, each value of \(\overline{V}\) worked as the center, and under the 4 randomness conditions that the values of the CVs of basic random variables were respectively 0.01, 0.03, 0.05 and 0.07, 20 sample points were randomly selected for each value of \(\overline{V}\), on which the repeated numerical simulations were conducted for the 0–1 recognition results of δ. Thus, the 1680-point test sample set was constructed in order to test the accuracy of the 3 ANNs in predicting the 0–1 recognition results of δ.

-

(2)

Determining the fitness function

This example took Eq. 17 as the fitness function of DLGABPNN and GABPNN.

where Fi is the fitness of the individual i, Ri is the test accuracy of ANN corresponding to the individual i, both C3 and C4 are the coefficients of this equation, and C3 > 0.

In Eq. 17, Fi is proportional to Ri. It ensures that DLGA and GA can optimize BPNN while improving the test accuracy of the BPNN, and thus obtain the surrogate model that can accurately predict the penetration results of the targets.

-

(3)

Determining the structure of and key parameters for ANNs

Since Cotter35 and Castro et al.36 have proven that the 3-layer forward ANNs can solve the majority of the nonlinear mapping problems, the DLGABPNN in this example adopted the single hidden-layer ANNs. Besides, with 11 basic random variables and an random response (δ) in this example, the quantity of the input-layer neurons of DLGABPNN was set to 11; that of the output-layer neurons 1; that of the hidden-layer neurons 15, thus constructing an DLGABPNN structure of \({11} \times {15} \times {1}\). Then, the maximum number of network training times Tmax was set to 20,000, the network training rate St 0.05, the allowable error Ea of network training 0.001, n1 10, NL 500, NB 10,000, Tend 5, PC 0.8, PM 0.1, and the coefficients C1, C2, C3 and C4 in Eq. 4, Eq. 5 and Eq. 17 were 0.2, 0.3, 120.0 and -100.0, respectively.

GABPNN had the same structure as DLGABPNN, with the population size Mp being 50 and the maximum reproduction generation Gmax being 60. The rest of the parameters were the same as their counterparts in DLGABPNN. And BPNN also had the same structure and parameters as DLGABPNN.

-

(4)

Performance comparison between DLGA and GA for BPNN optimization

Given the stochastic nature of DLGA and GA in optimizing BPNN, a rigorous comparative analysis was conducted for assessing their performances. Specifically, each was used to optimize BPNN in 200 random and independent trials. Also, BPNN was trained and tested 200 times randomly and independently as a comparison. The test accuracy values and their statistical characteristics of the 3 ANNs are shown in Fig. 5 and Table 4, and the serial numbers and statistical characteristics of the optimal individuals in the DLGA and GA populations are presented in Fig. 6 and Table 5.

As shown in Fig. 5 and Table 4, the 200 DLGABPNNs and 200 GABPNNs have very close mean test accuracy, both of which are significantly higher than the mean test accuracy of the 200 BPNNs. Also, the standard deviations of the test accuracy of DLGABPNNs and GABPNNs are similar and markedly lower than those of BPNNs. This means that DLGA and GA have comparable optimization effects on BPNN, and that each optimization yields the best-performing BPNN, with test accuracy stably around 0.98. In contrast, unoptimized BPNNs show substantially lower accuracy and greater variability, reflecting inherent instability and sub-optimal generalization.

Figure 6 and Table 5 indicate that the mean serial number of the 200 optimal individuals in DLGA populations is smaller than that in GA populations, while the standard deviation of these serial numbers for DLGA is comparable to that of GA. This suggests that DLGA generally achieves higher optimization efficiency than GA for BPNN, while the stability of its optimization efficiency remains statistically comparable to that of GA.

The comparative analysis of DLGA and GA in optimizing BPNN reveals the following key findings: both DLGA and GA demonstrate comparable performance in optimizing BPNN, consistently yielding optimal BPNN capable of accurately predicting the 0–1 recognition results of δ for APRMPS; however, DLGA exhibits superior optimization efficiency over GA. Thus, it is more reasonable to use DLGA in optimizing BPNN for the construction the surrogate model of APRMPS, and subsequent application of DLGABPNN-MCS reliably estimates the P’s of targets, meeting the accuracy requirements.

-

(5)

Estimating the P’s of the targets based on DLGABPNN-MCS

First, in the interval of \(V_{50} \pm {3}00\) m/s, being gradually increased by 10 m/s each time, each value of \(\overline{V}\) worked as the center, and under the 4 randomness conditions discussed above, 10,000 sample points were randomly selected for each value of \(\overline{V}\) to construct four 610,000-point prediction sample sets. Then, DLGABPNN-MCS was employed to obtain the 0–1 recognition results of δ of the 4 prediction sample sets, so as to obtain the estimates of the P’s of the targets corresponding to each value of \(\overline{V}\) under the 4 randomness conditions. Finally, 4 relation curves between P and \(\overline{V}\) (the P-\(\overline{V}\) curves) are drawn as shown in Fig. 7, on which the data in Table 6 are based.

Three observations can be obtained from Fig. 7 and Table 6. First, the \(\overline{V}_{50}\) of the targets calculated by DLGABPNN-MCS under the above 4 randomness conditions is consistently 819 m/s, nearly the same with the V50 (821 m/s) measured in the test20. This proves that DLGABPNN-MCS was perfectly accurate in estimating the P’s of the targets. Second, the P–\(\overline{V}\) curves are monotonically increasing curves that converge to 0% and 100% respectively at the left and right ends. This shows that under the action of basic random variables, when \(\overline{V} \le \overline{V}_{{0}},\) P = 0%, and the targets will definitely not be penetrated, that when \(\overline{V} \ge \overline{V}_{100}\), P = 100%, and the targets will certainly be penetrated, and that when \(\overline{V}_{0} < \overline{V} < \overline{V}_{100}\), whether the targets can be penetrated is random, with P increasing with \(\overline{V}\). Last, the larger the CVs of basic random variables, the stronger the randomness of the APRMPS, and the smaller the value of \(\overline{V}_{{0}}\) and the larger the value of \(\overline{V}_{{{100}}}\), which leads to a longer increasing interval of \([\overline{V}_{{0}} ,{\kern 1pt} \overline{V}_{{{100}}} ]\) of the P–\(\overline{V}\) curves, where the curves increase more steadily.

Example 2

This example employed the anti-penetration tests of the metal targets reported in Reference 21, in which the targets were 15 mm-thick plane aluminum alloy plates, and the fragments were steel cubes of a size of \({10}{\kern 1pt} \;{\text{mm}} \times {10}\;{\text{mm}} \times {8}\;{\text{mm}}\), with the measured result of V50 = 595.3 m/s and shear plugging.

Numerical model

For the repeated numerical simulations of the randomness study, this example adopted the same numerical simulation method and program as Example 1, and constructed a numerical model shown in Fig. 8. In addition, the steel had a density of 7.85 g/cm3 and the aluminum alloy 2.78 g/cm3. The deterministic parameter values for the Mie–Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model of the latter are shown in Tables 7, 8 and 9, and the deterministic parameter values of the three performance equations of steel are the same as those in Example 1 (See Tables 1, 2 and 3).

In order to verify the accuracy of the test results simulated by the GIMPM program, the penetration velocity of the fragments was set at \(V = V_{50} \pm 10\) m/s (i.e. 585.3 m/s and 605.3 m/s) and the numerical simulation results by the GIMPM program are shown in Fig. 9.

It can be seen from Fig. 9 that when V = 585.3 m/s, the fragment failed to penetrate the target, leaving a large depression of the target, and that when V = 605.3 m/s, the fragment successfully penetrated the target and caused shear plugging. These results are fully consistent with the test results21. Therefore, the GIMPM program is qualified to conduct accurate numerical simulations of this example.

Selection of basic random variables

The density of, and the parameters in the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model of the fragment material (steel) were labeled respectively as \(\rho_{{F{0}}}\),\(\gamma_{F0}\), aF, SF1, SF2, SF3, AF, BF, CF, nF, mF, DF1, DF2, DF3, DF4 and DF5, and the density of, and the parameters in the three performance equations of the target material (aluminum alloy) were marked respectively as \(\rho_{{T{0}}}\), \(\gamma_{T0}\), aT, ST1, ST2, ST3, AT, BT, CT, nT, mT, DT1, DT2, DT3, DT4 and DT5. It was also assumed that the 33 parameters were all independent of each other and subject to the normal distribution. By changing the values of these 33 parameters one by one and repeating the numerical simulation shown in section “Numerical model”, it was found that changing the values of the parameters V, \(\rho_{{F{0}}}\), \(\rho_{{T{0}}}\), AT, BT, nT, DT1 and DT2 could change the numerical simulation results. That is, when changing the values of these 8 parameters, it can lead the targets to be penetrated under the mean \(\overline{V}\) of V is 585.3 m/s, and not be penetrated under \(\overline{V}\) is 605.3 m/s. Thus it proves that these 8 parameters exert a significant influence on the penetration results of the targets in this study, so these 8 parameters were taken as the basic random variables of the APRMPS in this example.

APRMPS study

It was also assumed that the 8 basic random variables were all independent of each other and subject to the normal distribution, so the means of these basic random variables were their deterministic parameter values. And DLGABPNN-MCS was also employed to study the APRMPS under the 4 randomness conditions that the values of the CVs of these basic random variables were respectively 0.02, 0.04, 0.06 and 0.08. Like Example 1, in the ANN training and testing phases, BPNN and GABPNN worked as the performance comparison objects of DLGABPNN in order to discuss the advantages of DLGABPNN as a surrogate model for numerical models.

-

(1)

Constructing the training sample set and the test sample sets

First, under the randomness conditions that the CVs of basic random variables were all 0.1 and that \(\overline{V}\) = V50 (595.3 m/s), 2000 sample points were withdrawn by applying the Latin Hypercube Sampling, and then underwent the repeated numerical simulations for the 0–1 recognition results of δ, so as to construct a 2000-point training sample set for training the 3 ANNs. Then, in the interval of \(V_{50} \pm 100\) m/s, being gradually increased by 10 m/s each time, each value of \(\overline{V}\) worked as the center, and under the 4 randomness conditions that the values of the CVs of basic random variables were respectively 0.02, 0.04, 0.06 and 0.08, 20 sample points were randomly selected for each value of \(\overline{V}\), on which the repeated numerical simulations were conducted for the 0–1 recognition results of δ. Thus, the 1680-point test sample set was constructed in order to test the accuracy of the 3 ANNs in predicting the 0–1 recognition results of δ.

-

(2)

Determining the fitness function

This example also took Eq. 17 as the fitness function of DLGABPNN and GABPNN.

-

(3)

Determining the structure of and key parameters for ANNs

DLGABPNN, GABPNN and BPNN in this example adopted the single hidden-layer ANNs. Besides, with 8 basic random variables and an random response (δ) in this example, the quantities of the input-layer neurons of the 3 ANNs were set to 8; those of the output-layer neurons 1; those of the hidden-layer neurons 15, thus constructing the 3 ANNs with a structure of \({8} \times {15} \times {1}\). Then, the parameters of the ANNs in this example were the same as their counterparts in Example 1.

-

(4)

Performance comparison between DLGA and GA for BPNN optimization

A comparative analysis of DLGA and GA in optimizing BPNN was also conducted for assessing their performances. Similarly, each was used to optimize BPNN in 200 random and independent trials. Also, BPNN was trained and tested 200 times randomly and independently as a comparison. The test accuracy values and their statistical characteristics of the 3 ANNs are shown in Fig. 10 and Table 10, and the serial numbers and statistical characteristics of the optimal individuals in the DLGA and GA populations are presented in Fig. 11 and Table 11.

From Fig. 10 and Table 10, it can be seen that the 200 DLGABPNNs and 200 GABPNNs have very close mean test accuracy, both of which are significantly higher than the mean test accuracy of the 200 BPNNs. Also, the standard deviations of the test accuracy of DLGABPNNs and GABPNNs are similar and markedly lower than those of BPNNs. This means that DLGA and GA have comparable optimization effects on BPNN, and that each optimization yields the best-performing BPNN, with test accuracy stably around 0.97. In contrast, unoptimized BPNNs show substantially lower accuracy and greater variability, resulting in low and highly random test accuracy each time.

Figure 11 and Table 11 show that the mean of the serial numbers of the 200 optimal individuals of DLGA is smaller than that of GA, and the standard deviation of these serial numbers of the optimal individuals of DLGA is also smaller than that of GA. This means that DLGA generally achieves higher and more stable optimization efficiency than GA for BPNN.

The comparison above indicates that both DLGA and GA demonstrate comparable performance in optimizing BPNN, consistently yielding optimal BPNN capable of accurately predicting the 0–1 recognition results of δ for APRMPS, with DLGA exhibiting superior optimization efficiency over GA. Therefore, it is more reasonable to use DLGA in optimizing BPNN for the construction the surrogate model of APRMPS, and subsequent application of DLGABPNN-MCS reliably estimates the P’s of targets, meeting the accuracy requirements.

-

(5)

Estimating the P’s of the targets based on DLGABPNN-MCS

First, in the interval of \(V_{50} \pm {3}00\) m/s, being gradually increased by 10 m/s each time, each value of \(\overline{V}\) worked as the center, and under the 4 randomness conditions discussed above, 10,000 sample points are randomly selected for each value of \(\overline{V}\) to construct four 610,000-point prediction sample sets. Then, DLGABPNN-MCS was employed to obtain the 0–1 recognition results of δ of the 4 prediction sample sets, so as to obtain the estimates of the P’s of the targets corresponding to each value of \(\overline{V}\) under the 4 randomness conditions. Finally, 4 P-\(\overline{V}\) curves are drawn in Fig. 12, on which the data in Table 12 are based.

Figure 12 and Table 12 lead to three conclusions similar to those of Fig. 7 and Table 6 in Example 1. First, the \(\overline{V}_{50}\) of the targets calculated by DLGABPNN-MCS under the above 4 randomness conditions is consistently 597 m/s, nearly the same with the V50 (595.3 m/s) measured in the test21, which proves that DLGABPNN-MCS was perfectly accurate in estimating the P’s of the targets. Second, the P–\(\overline{V}\) curves are monotonically increasing curves that converge to 0% and 100% respectively at both ends. The last conclusion is that the larger CVs of basic random variables the longer increasing interval of \([\overline{V}_{{0}} ,{\kern 1pt} \overline{V}_{{{100}}} ]\) of the P–\(\overline{V}\) curves.

Discussion

This paper contributes 2 primary innovations. First, it analyzes APRMPS and systematically investigates its potential candidates for basic random variables, introducing δ as the random response of APRMPS. Second, it proposes DLGA by improving GA, and presents the main process of optimizing BPNN using DLGA and the technical route to addressing APRMPS with DLGABPNN-MCS. By applying this method, the penetration probabilities of metal protective structures under the action of basic random variables can be obtained.

However, 3 aspects of this paper still need improvement in future study. First, the randomness of parameters in the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model, and the Johnson–Cook failure model for metallic materials requires extensive experimental validation. Future studies may conduct systematic experiments by employing Bayesian sampling to quantify statistical distributions of these parameters for the three equations and to investigate their impact on the stochasticity of metallic material dynamics. Second, this paper focuses on the anti-penetration randomness of single metallic structures under fragment impact, while composite material structures are also commonly used in armor protection in engineering. Thus, it is necessary to further investigate the anti-penetration randomness of composite material structures in future research. Third, this paper proposes DLGA based on the improvement of GA and applies it to optimize BPNN for the surrogate model, while emerging artificial intelligence and machine learning offer promising alternatives, as suggested in References5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Therefore, future studies will explore other state-of-the-art ANNs as surrogate models to investigate engineering problems such as the anti-penetration randomness of protective structures and structural health monitoring.

Conclusion

It is necessary to extend the anti-penetration of metal protective structures to APRMPS and to apply ANN-MCS in the APRMPS study for the penetration probabilities of metal protective structures under the action of basic random variables. From the density of, and the parameters for the Mie-Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model of the materials of the metal protective structures and the fragments, this method also selects the parameters exerting significant effects on the penetration results of metal protective structures as the basic random variables of APRMPS. It takes δ, which represents whether metal protective structures are penetrated, as the random response of APRMPS.

Moreover, DLGA proposed in this paper removes the selection operation and constructs the life cycles of individuals, in which each individual automatically follows its development and reproduction, so as to reduce the human intervention and ensure the natural evolution of the population, hence a higher optimization efficiency of DLGA, compared to GA. Also, this paper presents the main processes of the optimization of BPNN by DLGA and the technical route of DLGABPNN-MCS to addressing APRMPS, demonstrates the specific procedures for this method in the two applied examples of the anti-penetration randomness of metal targets, proves the higher efficiency of DLGA than GA in optimizing BPNN, and verifies the effectiveness of DLGABPNN-MCS in studying APRMPS.

In addition, Like GA, DLGA is also a universal heuristic algorithm for resolving various optimization problems, including optimizing ANNs, it is advisable to extend its application in follow-up study for the exploration of other optimization problems. Besides, since this is the debut of DLGA, there is still much room for the improvement of the technical details, such as life expectancy function, reproductive chromosome quantity function and specific procedures of DLGA.

Furthermore, future studies should conduct in-depth research into the randomness of parameters in the Mie–Grüneisen equation of state, the Johnson–Cook plasticity model and the Johnson–Cook failure model to uncover their statistical patterns and impacts on the stochastic dynamic behavior of these materials. It is also essential to explore the anti-penetration randomness of composite material protective structures and other complex structures. Additionally, more advanced ANNs should be employed as surrogate models to investigate engineering problems such as the anti-penetration randomness of protective structures and structural health monitoring.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Sevkat, E. Experimental and numerical approaches for estimating ballistic limit velocities of woven composite beams. Int. J. Impact Eng. 45, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2012.01.007 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Effects of water on the ballistic performance of para-aramid fabrics: Three different projectiles. Text. Res. J. 86(13), 1372–1384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517515612355 (2016).

Ali, A. et al. Ballistic impact properties of woven bamboo-woven E-glass-unsaturated polyester hybrid composites. Def. Technol. 15(3), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2018.09.001 (2019).

Cho, C. et al. Evaluation of ballistic limit velocity using instrumented indentation test of 7xxx aluminum alloys after friction stir welding. Met. Mater. Int. 27(7), 2264–2275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12540-020-00680-2 (2021).

Khatir, A. et al. Multiple damage detection and localization in beam-like and complex structures using co-ordinate modal assurance criterion combined with firefly and genetic algorithms. J. Vibroeng. 20(1), 832–842. https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2016.19719 (2016).

Khatir, A. et al. An efficient improved gradient boosting for strain prediction in near-surface mounted fiber-reinforced polymer strengthened reinforced concrete beam. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 18(8), 1148–1168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-024-1079-x (2024).

Khatir, A. et al. Advancing structural integrity prediction with optimized neural network and vibration analysis. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 9(3), 2390258. https://doi.org/10.1080/24705314.2024.2390258 (2024).

Khatir, A. et al. Enhancing damage detection using reptile search algorithm optimized neural network and frequency response function. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 13, 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-024-01545-3 (2025).

Khatir, A. et al. A new hybrid PSO-YUKI for double cracks identification in CFRP cantilever beam. Compos. Struct. 311, 116803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.116803 (2023).

Khatir, A. et al. Vibration-based crack prediction on a beam model using hybrid butterfly optimization algorithm with artificial neural network. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 16(8), 976–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-022-0840-2 (2022).

Achouri, F. et al. Structural health monitoring of beam model based on swarm intelligence-based algorithms and neural networks employing FR. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 45, 621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-023-04525-y (2023).

Wang, Y. L., Liu, Y. & Che, S. B. Research on pattern recognition based on BP neural network. Adv. Mater. Res. 282–283, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.282-283.161 (2011).

Xue, Z. C. & Wang, H. J. The application of artificial BP neural networks and Monte-Carlo method for the reliability analysis on frame structure. Appl. Mech. Mater. 204–208, 3256–3259. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.204-208.3256 (2012).

Yang, A. M. et al. Design of intrusion detection system for internet of things based on improved BP neural network. IEEE Access 7, 106043–106052. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2929919 (2019).

Zhao CJ. Research of Expression Recognition Base on Optimized BP Neural Network. In 16th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, China, Beijing vol. 1–2 1803–1806. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIEEM.2009.5344321 (2009).

Zheng, B. H. Material procedure quality forecast based on genetic BP neural network. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 31(19–21), 1740080. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984917400802 (2017).

Li, H. X. et al. Application of BP neural network based on genetic algorithm optimization. In 4th International Conference on Intelligent Information Processing, China, Guilin 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1145/3378065.3378096 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Study on shock initiation randomness of energetic materials on a macroscopic scale. Appl. Sci. 13(4), 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042534 (2023).

Chen, W. D. et al. Stochastic material point method for analysis in non-linear dynamics of metals. Metals 9(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9010107 (2019).

Cheng, Y. et al. Influence of dimensionless parameters on ballistic limit velocity of fragments. J. Ballist. 34(4), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.12115/j.issn.1004-499X(2022)04-002 (2022).

Xin, T. & Han, Q. Research on ballistic limit velocity of steel fragments penetrating target. Sci. Technol. Eng. 12(2), 264–268. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2012.02.004 (2012).

Jiang, D. et al. Penetration of confined AD95 ceramic composite targets by tungsten long rods. Explos. Shock Waves 30(1), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1455.2010.01.015 (2010).

Holmquist, T. J., Templeton, D. W. & Bishnoi, K. D. Constitutive modeling of aluminum nitride for large strain, high-strain rate, and high-pressure applications. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 25(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(00)00046-4 (2001).

Quan, X. et al. Numerical simulation of long rods impacting silicon carbide targets using JH-1 model. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 33(1–12), 634–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2006.09.011 (2006).

Liu, Z. Q. et al. State-of-the-art of constitutive equations in metal cutting operations. Tool Eng. 42(3), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.16567/j.cnki.1000-7008.2008.03.018 (2008).

Cullis, I. G. & Lynch, N. J. Performance of model scale lone rod projectiles against complex targets over the velocity range 1700–2200 m/s. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 17, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/0734-743X(95)99852-I (1995).

Normandia, M. J. & Lee, M. Penetration performance of multiple segmented rods at 26 km/s. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 23, 675–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(99)00113-X (1999).

Chen, W. D. et al. A stochastic material point method for probabilistic dynamics and reliability. Comput. Mech. 63(5), 1069–1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1667-5 (2019).

Han, L. Q. & Shi, Y. Artificial Neural Network Theory and Application 1st edn, 42–76 (China Machine Press, 2018).

Bardenhagen, S. G. & Kober, E. M. The generalized interpolation material point method. CMES Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 5, 477–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-004-0004-3 (2004).

Chen, W. D. et al. Improvement of the material point method and its application in explosion and impact dynamics. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 42(11), 1671–1678. https://doi.org/10.11990/jheu.202008057 (2021).

Zhang, S. W. et al. Measuring and numerical simulation of attenuation of planar shock wave in PMMA. Acta Armamentarii 37(7), 1214–1219. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1093.2016.07.008 (2016).

Xu, Y. X., Ren, J. & Wang, S. S. Research on perforation limit thickness of low carbon steel plates impacted normally by tungsten spheres. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 37(6), 551–556. https://doi.org/10.15918/j.tbit1001-0645.2017.06.001 (2017).

Cheng, Y. et al. A numerical simulation study of typical cube fragments invading armored steel. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 43(8), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.11809/bqzbgcxb2022.08.016 (2022).

Cotter, N. E. The stone-weierstrass theorem and its application to neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1, 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1109/72.80265 (1990).

Castro, J. L., Mantas, C. J. & Benitez, J. M. Neural networks with a continuous squashing function in the output are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 13, 561–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-6080(00)00031-9 (2000).

Buyuk, M. et al. Automated design of threats and shields under hypervelocity impacts by using successive optimization methodology. Int. J. Impact Eng. 35(12), 1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2008.07.057 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and W.C.; methodology, L.L., W.C., and S.L.; software, Y.Y.; validation, L.L. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L., S.L., and M.S.; data curation, L.L., S.L., and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, W.C. and S.L.; supervision, W.C. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Chen, W., Lu, S. et al. Study on the anti-penetration randomness of metal protective structures based on optimized artificial neural network. Sci Rep 15, 16506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00174-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00174-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on the randomness of the peak pressure of spherical blast waves

Scientific Reports (2025)