Abstract

The World Health Organization recommends a daily salt intake of less than 5.0 g. Similarly, Malaysia’s Salt Reduction Strategy to Prevent and Control Non-communicable Diseases (2021–2025) targets a daily intake of less than 6.0 g by 2025, achievable through salt reduction in processed and prepared foods. However, the lack of maximum salt targets for food businesses to adhere to, poses a potential challenge to the effectiveness of salt reduction efforts. This paper presents a step-wise approach to propose maximum salt targets in key food categories, paving the way for mandatory or voluntary policy interventions. Following a step-wise approach by Downs et al. (2015) for setting national salt targets, this study systematically proposed maximum salt targets for selected food categories. Steps included: (1) identifying major contributors to dietary salt; (2) selecting target food categories; and (3) establishing target levels. Steps 1 and 2 were performed by reviewing literature from local dietary survey and analyzing street food nutrient content as well as retrieving secondary data from previous market surveys. An additional market survey was conducted in February 2024 following the gazettement of mandatory sodium labelling in January 2024. Scatter plot analysis, literature reviews and expert consultations were used to achieve Step 3. Step 1 identified that the major contributors to Malaysia’s salt intake are cooked food and processed foods. A total of 14 food categories under the Food Regulation 1985 were selected for target setting based on their contribution to dietary salt intake and relevance to ongoing revision in the Malaysia Food Act 1983 (Step 2). The 75th percentile sodium level was selected as the maximum salt target and adjusted by a further 10–20% reduction based on sales data from a reputable source (Step 3). This study proposed maximum salt targets for 14 food categories, which are recognised as major contributors to salt intake in Malaysian diets. There is a need to further engage with stakeholders and develop monitoring mechanisms to support the implementation of maximum salt targets as well as evaluating consumer behaviour changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as coronary artery disease and stroke, are the leading cause of global deaths, accounting for 32% of all fatalities1. In Malaysia, hypertension is a primary contributor to CVDs, affecting around 30% (approximately 6.4 million) of adults aged 18 and above2. The Malaysian Community Salt Survey (MyCoSS) (2017–2018), revealed that 79% of Malaysians consume excessive salt3with an average intake of 7.9 g/day, surpassing the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended intake of less than 5.0 g/day3,4.

Reducing salt intake is one of the most cost-effective strategies for preventing CVDs5. While many countries are leaning towards regulatory approaches, there remains an urgent need to expedite these endeavors and enhance monitoring and evaluation strategies to meet salt reduction targets6. Malaysia’s Salt Reduction Strategy to Prevent and Control Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) (2021–2025) aims for a daily intake of 6.0 g by 2025. One key recommendation is comprehensive monitoring of salt content in ready-to-eat processed foods7. A supplementary strategy focuses on the out-of-home sector, which often lacks salt targets and serve high-salt foods8.

Prepared and processed foods typically contain high levels of ‘hidden salt’, which consumers are often unaware of9. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), high salt consumption is often associated with discretionary salt usage in cooking and condiments like fish sauce and soy sauce10. Street vendors and food establishments also offer high-salt foods as evidenced through the food analyses of street food11. Encouraging the food industry to reduce salt content in food through targets or standards may effectively decrease population salt consumption12. These initiatives can be mandatory (salt standards) or voluntary (salt targets). Most salt reduction initiatives are voluntary13, but some countries, like South Africa, have imposed mandatory limits14.

The United Kingdom (UK) led the way with comprehensive voluntary salt targets, reducing dietary salt intake by 1.4 g/day between 2003 and 2011, coinciding with a significant decrease in population blood pressure and mortality from stroke and ischemic heart disease (IHD)15. This highlights the impact of salt targets in advancing global objectives to reduce salt intake by 30% and mitigate diet-related NCDs. South Africa’s 2016 legislation mandating maximum sodium levels in processed foods has resulted in a decline in salt intake16.

LMICs face challenges in setting targets due to a lack of accessible data and limited capacity for implementation, enforcement, and monitoring. A practical approach is needed to establish country- or region-specific salt targets. Malaysia, as an upper middle-income country also, struggled with strategy implementation due to the lack of mandatory sodium content declarations on packaged foods7. Despite continuous efforts since 2016, mandatory sodium labelling was enforced only in January 2024. Encouraging voluntary salt reduction has been part of the strategy, but the absence of specific targets for reformulation poses a potential gap in its effectiveness. Our previous supplementary document also proposed maximum salt target for 14 food categories8. Besides, proposals for maximum salt targets for major contributors to salt intake, identified through previous surveys17,18,19,20, require updated market survey data after the mandatory sodium labelling enforcement and robust justifications, especially concerning international trade and public health objectives. Thus, this study aimed to propose maximum salt targets of selected food groups as part of the salt reduction strategies for Malaysia.

Methods

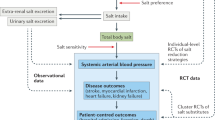

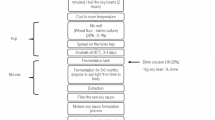

The step-wise approach to set national salt targets as suggested by Downs et al.21 was adopted to systematically propose maximum salt targets for 14 food categories under the Food Regulation 1985 (Fig. 1). This approach comprised of five steps (Step 1: identify sources of salt in the diet; Step 2: select foods for target setting; Step 3: select targets; Step 4: engage with stakeholders and Step 5: monitor progress) and this paper has focused on Step 1 through 3. Table 1 illustrates the types of foods proposed for maximum salt targets under this classification. Two of the 14 categories had already been included in a reformulation project (salty soy sauce & fish keropok)24,33.

The sources of dietary salt were identified in Step 1 by reviewing data on dietary intake (Step 1 A) from MyCoSS3. Further information about the salt levels in foods (Step 1B) were obtained from previous market surveys on specific food categories and street food analysis11. Secondary data was retrieved from previous market surveys on bread, processed food, sauces and instant noodles conducted between 2017 and 202117,18,19,20 to build a comprehensive food database. It is important to note that the mandatory Nutrition Information Panel labelling for sodium was only enforced in January 2024, leading to small sample sizes (i.e. fewer than 20 products) for some food categories. To increase the sample sizes, an additional market survey was conducted in February 2024 to update the data on sodium content in food products. Surveys involved supermarkets and retailers in Central Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur and the corresponding brand’s official websites. These supermarkets were selected based on the previous market surveys mentioned beforehand. The headquarters of these companies, usually located in Kuala Lumpur, produce the product and distribute it to the rest of Malaysia, making it representative of the Malaysian market.

Data was collected using the nutrition labels found on product packaging. For each product, a photo of the nutrition information panel was taken and the manufacturer (local or imported), brand, product name, and amount of sodium per 100 g were recorded. This information was extracted and entered into a spreadsheet to build a database. To ensure data accuracy, our research team conducted random checks during multiple meetings, resulting in a 0% error rate. Mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values of sodium content (mg per 100 g) were calculated using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0.

Salt level targets in foods prioritize categories that significantly contribute to dietary salt intake (Step 2). The selection of 14 food categories identified under the Food Regulation 1985 was informed by previous surveys conducted in Step 1 and the ongoing revision of Malaysia Food Act 1983 since 2020 (Step 2 A). Step 3 involved setting salt targets by assessing the current range of products and their existing salt levels, and comparing them to targets from other countries (Step 3 A). In Step 3B, a literature review was conducted to understand how maximum salt levels have been established globally (Table 2). Following discussion with research teams, the 75th percentile of sodium levels of each food category was proposed as the maximum salt target (Step 3)22. The chosen cut-off point was based on Canada’s guidelines. Health Canada’s guidelines specify sodium limits for various processed food categories, aiming to guide the food industry in reducing sodium content22. The values were subsequently adjusted based on sales data from a reputable source (unpublished data) of which mean sodium level of the top five brands was examined. If the mean sodium level of the top five brands within a food category was lower than the 75th percentile, the proposed maximum salt target was reduced accordingly. A reduction of 10–20% from the 75th percentile of sodium levels was used as a guide23 in consultation with food technologists in our research team. This adjustment was intended to ensure that the maximum salt target would have an impact on reducing population salt intakes.

However, for the sweet, dark, and salty soy sauce, the proposed maximum target is set at 4400 mg, lower than the 75th percentile value of 5400 mg, based on successful reformulation efforts achieving this sodium content24. Consumer acceptance favored soy sauce with 4400 mg of sodium over higher sodium alternatives. These targets aim to challenge manufacturers while promoting public health25. Scatter plots were used to visualize each category’s sodium content (Appendix A-D), benchmarking them against international standards and practices.

Results

Step 1 involved identifying the sources of salt in the Malaysian diet. Dietary intake data was obtained from MyCoSS, a cross-sectional, population-based household survey conducted by the Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia31. Salt intake was estimated using a single 24-hour urine collection from 960 participants, revealing a mean urinary sodium excretion of 3167 mg/day (95% CI: 2987, 3346). This corresponds to approximately 7.9 g/day of salt, with 4 out of 5 Malaysian adults consuming salt levels above the WHO recommendation3. Factors associated with high salt intake included obesity, large waist circumference, male gender, urban living, and younger adulthood31.

The MyCoSS study identified the primary sources of dietary salt through a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) completed by 1032 participants. The top 10 contributors to salt intake included Mee kolok/Kampua (savoury dry noodle dish), light soy sauce, curry noodle, vegetable with salted fish, fried vegetables, roti canai (Malaysian flatbread) and fried rice. Overall, cooked food emerged as the major contributor to salt in the Malaysian diet. It shows that Malaysian use excessive salt during food preparation, even for meals prepared outside of the home. This is because many ingredients used in home cooking, such as sauces, seasonings, and ready-made products, come from processed and packaged foods which are often a hidden source of salt32. In 2021, a food sampling and analysis of street foods across Malaysia found that snacks (such as fried fish ball, fried sausage, fried chicken, chicken nuggets etc.) contained the highest salt levels (1.1 g/100 g), followed by main meals (0.8 g/100 g). Fried noodles and noodle soup were particularly high in salt (> 5 g salt per serving) due to the incorporation of various high-salt sauces11.

The understanding of sources of dietary salt was further refined through market surveys conducted between 2017 and 2021, prior to the enforcement of mandatory sodium labelling. A cross-sectional market survey in 2017, involving 233 sauces sold in Malaysian supermarkets, found that 49.8% did not display salt content information. The highest salt content was found in fish/prawn sauce (budu/cencalok) (13.0 g/100 g), light/thin soy sauce (12.8 g/100 g), and salty soy sauce (11.9 g/100 g)18. Another 2017 survey of 707 instant noodles products revealed that only 62.1% provided salt content information, with a mean salt content of 4.3 ± 1.5 g/100 g. A total of 11.8% of the instant noodles exceeded WHO’s recommended daily salt intake17. Another market survey on processed foods revealed that the category with the highest average salt content was gravy and sauce (3.97 g/100 g), followed by soup (2.95 g/100 g) and cheese (2.14 g/100 g)19. Table 3 provides a summary of the information discussed earlier.

Based on the salt sources identified in Step 1, we prioritized specific food categories for target setting in Step 2. Additionally, since 2020, the Food Safety and Quality (FSQ) Division of the MOH has been revising certain food categories under the Malaysia Food Act 1983, including soy sauce, fish products, meat products, cereals and cheese. These food categories were therefore prioritized for target establishment. Consequently, the selected food categories for setting salt targets were the 14 categories under the Food Regulation 1985, identified as major contributors to salt intake based on extensive previous surveys. For Regulation 149 and Regulation 151, we separated them into two categories: Regulation 149 for canned meat with more than 90% meat and Regulation 151 for canned meat with more than 45% but below 90% meat. Additionally, for soya sauce, soya bean sauce or kicap(e.g., light/salty/sweet) under Regulation 340 and Regulation 341, we separated them into two categories1: sweet, salty, and dark soy sauce, and2 light soy sauce. This separation is necessary because light soy sauce has a slightly higher sodium content, making it less suitable to group with other soy sauces for establishing the same maximum salt target.

Table 4 presents a comprehensive overview of sodium labelling and sample collection in 14 food categories in Malaysia, encompassing a total of 1431 food items. The largest sample size was observed in instant noodles. Meanwhile processed cheese, which was entirely imported, was consistently labelled. However, locally produced products like manufactured meat and fish keropok often lacked sodium labelling, indicating the need for enhanced labelling practices. In contrast, canned fish, breakfast cereals, butter, margarine, and soups demonstrated a mix of local and imported sources, with varying degrees of sodium labelling. Following the gazettement of mandatory sodium labelling on January 1, 2024 in Malaysia, there has been a notable increase in sodium labelling practices in locally produced products over the years. The data collection spanned multiple years, primarily from 2017 to 2024, reflecting continuous efforts to monitor sodium content in the market. This data highlights the variability in sodium labelling across different food categories and emphasizes the need for continued monitoring to ensure compliance.

In Table 5, the sodium content across the 14 food categories in the Malaysian market is compared between local and imported products. Instant noodles, processed cheese, soup stock, chilli sauces and soy sauces were found to have sodium contents exceeding 1000 mg/100 g, with soup stock exhibiting the highest sodium content. Imported products including instant noodles, prepared cereal food, canned meat (> 90% meat), chilli sauces, tomato sauces and soy sauces, generally demonstrated higher sodium content compared to local products, indicating the necessity for more stringent control over the import of high-sodium food products. The boxplot for each food category, depicting their respective mean and proposed maximum salt target was illustrated (Appendix A to D). The number of food products which exceeded the proposed maximum salt target was indicated together with their percentage in brackets.

Table 6a and 6b show the sodium content in 14 food categories in Malaysia, focusing on the proposed maximum salt target and comparing them with international sodium reduction targets (Step 3). While a notable proportion of products exceeded the proposed maximum salt targets, all remained below 60%, ranging from 16.3 to 57.1%. The analysis shows that instant noodles (49.6%), margarine (55.9%), and chilli sauce (57.1%) need to be reformulated to achieve the proposed sodium targets. Whilst, a lower proportion of products for food category butter (14.3%), canned meat (> 45% meat) (23.8%), and fish keropok (25.0%) were found to be above the proposed sodium target and need to be reformulated. The proposed maximum sodium targets for selected food categories in Malaysia are generally higher than those set by South Africa, Argentina, and the UK. Specifically, all Malaysian food categories, except for manufactured meat, have higher sodium targets than South Africa’s mandatory maximum levels. Similarly, the proposed target for manufactured meat aligns with Argentina’s mandatory and regional standards as well as the UK’s voluntary targets. Furthermore, when compared to the WHO global benchmark, the proposed sodium targets for all 14 Malaysian food categories are higher than the target levels except for sweet, salty and dark soy sauce. Notably, the proposed targets for tomato sauce, as well as sweet, salty, and dark soy sauce, are below the WHO South-East Asian Regional Sodium Benchmark; however, the remaining categories exceed these regional standards. Additionally, Malaysia’s proposed sodium target for instant noodles, soup, soup stock, tomato sauces and light soy sauces are higher than Canada’s voluntary maximum targets. Moreover, the reformulation target set by Australia indicates that the prepared cereal food targets in Malaysia are higher. Finally, the target values for all Malaysian food categories are comparable to the USA’s voluntary maximum targets. In summary, the feasibility of Malaysia’s proposed maximum sodium targets is supported by the fact that most of these targets are higher than the WHO benchmarks and those of other countries.

Discussions

This study has proposed maximum salt targets for 14 food categories under the Food Regulation 1985. These targets were determined using a systematic approach outlined by Downs et al.21, which takes into account the dietary salt intake of the Malaysian population and market surveys identifying the food categories contributing the most salt to population diet. In addition to these methods, the targets were further validated by sodium analysis from food sampling of popular street foods, ensuring that the targets are aligned with actual consumption patterns. The interests of policymakers were also considered to ensure that the targets are both practical and implementable. This comprehensive, evidence-based approach not only sets realistic maximum salt targets but also provides a sustainable framework for reducing salt consumption in Malaysia. By considering both market data and actual sodium intake, this method offers a balanced strategy that supports public health goals while being mindful of industry and regulatory perspectives. This study has also produced a complete database of salt content of leading contributors of salt to the Malaysian diet which provides a baseline against the national law standards. This will be essential for future comparisons and monitoring purposes. The database will be updated regularly in order to better evaluate the progress of the current reformulation policy in Malaysia41.

The high variability of sodium content found within each category also shows the technical feasibility of reducing sodium levels within these food groups, given similar food products with much lower sodium levels are already on the market42, as has been found in other studies around the world43,44. As compared with other standards22,34,35,36,37,39,40, a significant finding of this study is the notable diversity in sodium levels within the same food groups and categories. However, this variation could be attributed to the different processing methods used for each food category across countries, which should be taken into consideration. These findings underscore that a significant proportion of food products in Malaysia contain sodium levels exceeding international targets, highlighting the urgent need for Malaysia to implement stringent sodium reduction policies and enforcement mechanisms to align with global standards. This highlights the practical possibility of introducing lower sodium food items into the market by reformulating the existing food products and indicates that gradual, step-by-step reductions are achievable41. The study can independently monitor changes in sodium levels across the 14 selected food categories available in the Malaysian market. Our data will not only allow for long-term analysis but also provide valuable insights for comparing sodium content across different countries. The findings also indicate that most of the products in the 14 categories are produced locally, thereby suggesting that reformulation efforts are a possible and tangible target for the reduction of sodium intake in Malaysia18.

When determining the appropriate levels of salt in foods, it is important to consider various factors. These factors include assessing the current salt levels in products, their contribution to the population’s salt intake, comparing the targets with those set by other countries, evaluating the technical feasibility and safety implications of changing salt levels, as well as considering consumer acceptability and the origin of the products25. Thus, this study set the maximum salt target at the 75 th percentile of sodium levels to balance public health goals with industry feasibility22. By encouraging gradual salt reduction, this approach helps manufacturers lower the salt content of their products without making drastic changes that could affect taste and consumer acceptance. The 75 th percentile serves as a realistic and achievable benchmark, fostering compliance and cooperation within the food industry while promoting gradual reformulation. This strategy not only aligns with successful international practices but also aims to significantly reduce excessive salt consumption, thereby improving public health outcomes without imposing unrealistic demands on food producers.

For Malaysia, it is valuable to reference existing targets from other nations and conduct surveys to identify the range of available products in the local market. Countries such as the UK, US, Canada, Australia, and those endorsed by the WHO have established voluntary targets through extensive consultation processes. These targets can be adopted or modified to suit specific country or regional needs22,36,37,39,40. Additionally, mandatory salt standards implemented in Argentina and South Africa could serve as useful benchmarks34,35. Salt targets can be established as either mandatory or voluntary, depending on the country’s regulatory framework and industry dynamics. Developed countries like the US, UK, Australia, and Canada have implemented voluntary salt targets, which have been effective due to strong adherence from the food industry. However, in LMICs such as Argentina, mandatory targets have been set to ensure compliance, given the different market conditions and public health challenges. Following this approach, Malaysia plans to propose mandatory maximum salt targets to effectively reduce sodium intake. Moving forward, this will involve engaging stakeholders, including local food industry representatives, to ensure the targets are practical and enforceable. Additionally, establishing a robust monitoring mechanism will be crucial for tracking progress and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the salt reduction strategy. This includes developing an algorithm to regularly assess compliance and make necessary adjustments to the targets, ensuring that the initiative remains effective in improving public health outcomes.

A key strength of this study is its collaborative approach, involving a wide range of stakeholders, including experts from academia, public health and policymakers. Representatives from the food industry and officers from the FSQ, will be engaged in a later phase for implementation, including preparations for regulatory amendments. This inclusive strategy ensured that the proposed maximum salt targets were scientifically sound, realistic, and aligned with national health objectives and regulatory frameworks. By seeking broad consensus, the study increased the likelihood of successful implementation and compliance, promoting shared responsibility in reducing salt intake for improved public health. This study focuses not only on processed food but also on the seasoning and sauces used in cooked food, which will further contribute to the sodium reduction efforts. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the limitation of our study in not including the sodium content of cooked food and meals eaten outside the home directly, as obtaining reliable data on their sodium levels is challenging. More laboratory analyses are needed for accurate sodium level assessment, which would provide a more comprehensive understanding of dietary sodium intake. Future research should focus on conducting such analyses to strengthen sodium reduction strategies.

Apart from that, not all food categories met the required sample size criteria. However, the data collection process was conducted systematically, and the smaller sample sizes indicate either the availability of products in the market or the lack of nutrient labelling. Another limitation is that the sodium content that was considered for the analyses relied on food labelling and assumed that the manufacturers provided it accurately, without chemical analysis verification. Moreover, some local products produced from SMEs in certain states such as Sabah and Sarawak were not included. However, data collection in different regions of Malaysia will be conducted in the future to include these products.

Last but not least, the sales data provided by the reputable source (unpublished data), categorized according to their own food classifications, did not align exactly with the food categories as defined in the Food Regulation 1985. As a result, sales data for the top five brands in certain categories may not fully reflect the categories specified under the Food Regulation 1985. Additionally, variations in comparison of maximum salt targets across countries may be influenced by differences in how food categories are defined and variations in food processing methods.

Conclusions

This study proposed maximum salt targets for 14 food categories in Malaysia, which are major contributors of salt intake, identified via population consumption data, market surveys and food analysis. Future research should prioritize planning for stakeholder engagement and developing monitoring mechanisms to support the implementation of maximum salt targets as well as evaluating consumer behaviour changes. While successful implementation of the proposed sodium targets is expected to support Malaysia’s salt reduction initiatives, additional strategies addressing sodium levels in cooked food and meals eaten outside the home is deemed necessary to be outlined for a more comprehensive approach. It can ultimately improve public health outcomes and reduce the risk of salt-related diseases among the population.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request from our corresponding and main author: SS (suzana.shahar@ukm.edu.my) and YQO (ongyingqian@ukm.edu.my).

Abbreviations

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- FSQ:

-

Food Safety and Quality Division

- WTO:

-

World Trade Organization

References

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). (2021). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds). Accessed 14 Mar 2024.

Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: NCDs - non-communicable diseases: Risk factors and other health problems. (2019). http://www.iku.gov.my/nhms-2019

Ambak, R. et al. Salt intake was higher among males and those with high BMI and waist circumference: introduction to the Malaysian community salt survey (MyCoSS), a population-based salt intake survey in Malaysia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 40(Suppl 1), 23 (2021).

World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. (2012). http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77985%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Sodium%5BTitle%5D. Accessed 14 Mar 2024.

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. (2013). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892415062362013. Accessed 14 Mar 2024.

Santos, J. A. et al. A systematic review of salt reduction initiatives around the world: A midterm evaluation of progress towards the 2025 global non-communicable diseases salt reduction target. Adv. Nutr. 12(5), 1768–1780 (2021).

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Salt reduction strategy to prevent and control NCD for Malaysia 2021–2025. Putrajaya, Malaysia. (2021). https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Rujukan/NCD/Garam/Salt_Reduction_Strategy_To_Prevent_And_Control_NCD_For_Malaysia_2021-2025_26082021.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2024.

Harun, Z. et al. Salt reduction policy for out of home sectors: a supplementary document for the salt reduction strategy to prevent and control non-communicable diseases (NCDS) in Malaysia 2021–2025. Health Res. Policy Syst. 22(1), 49 (2024).

He, F. J., Campbell, N. R. C. & MacGregor, G. A. Reducing salt intake to prevent hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica. 32(4), 293–300 (2012).

World Health Organization. Salt intake. (2024). https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/salt-intake Accessed 14 Mar 2024.

Haron, H. et al. Str. Food Malaysia: What Are Sodium Levels?? Foods ;11(23):3791. (2022).

Vos, T. et al. Assessing cost-effectiveness in prevention (ACE-prevention). University of Queensland, Brisbane and Deakin University, Melbourne. (2010). http://www.sph.uq.edu.au/docs/BODCE/ACE-P/ACE-Prevention_final_report.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2024.

Webster, J. L., Dunford, E. K., Hawkes, C. & Neal, B. C. Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J. Hypertens. 29(6), 1043–1050 (2011).

Webster, J., Trieu, K., Dunford, E. & Hawkes, C. Target salt 2025: A global overview of National programs to encourage the food industry to reduce salt in foods. Nutrients 6(8), 3274 (2014).

He, F. J., Pombo-Rodrigues, S. & MacGregor, G. A. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open. 4(4), e004549 (2014).

Charlton, K. E. et al. Effect of South Africa’s interim mandatory salt reduction programme on urinary sodium excretion and blood pressure. Prev. Med. Rep. 23, 101469 (2021).

Tan, C. H. et al. Salt content of instant noodles in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 9(4), 1–10 (2019).

Shahar, S. et al. Sodium content in sauces-a major contributor of sodium intake in Malaysia: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. ;9(5). (2019).

Haron, H., Hiew, I., Shahar, S., Michael, V. & Ambak, R. A survey on salt content labeling of the processed food available in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health ;17(7). (2020).

Chow, J. Y., Shahar, S., Haron, H. & Ong, Y. Q. Market survey of the food additive–Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) in savoury processed foods in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nutritional Science. Submitted. (2024).

Downs, S. M. et al. Setting targets for salt levels in foods: A five-step approach for low- and middle-income countries. Food Policy. 55, 101–108 (2015).

Health Canada. Guidance for the food industry on reducing sodium in processed foods. (2012). https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/legislation-guidelines/guidance-documents/guidance-food-industry-reducing-sodium-processed-foods-2012.html. Accessed 19 Apr 2024.

WHO SAERO Salt Reduction Toolkit. Setting Salt Reduction Targets. (2023).

Harun, Z. et al. Reformulating soy sauce to lower sodium content: a mixed methods study to assess scope for reformulation, manufacturer readiness, consumer acceptability and shelf-life stability. PLoS One. Submitted. (2024).

Charlton, K., Webster, J. & Kowal, P. To legislate or not to legislate? A comparison of the UK and South African approaches to the development and implementation of salt reduction programs. Nutrients 6(9), 3672–3695 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. Setting sodium targets for pre-packaged foods in China — an exploratory study. Front. Nutr. 10, 1231979 (2023).

Campbell, N. et al. Targets and timelines for reducing salt in processed food in the Americas. J. Clin. Hypertens. 16(9), 619–623 (2014).

He, F. J., Brinsden, H. C. & Macgregor, G. A. Salt reduction in the united Kingdom: A successful experiment in public health. J. Hum. Hypertens. 28(6), 345–352 (2014).

Charlton, K. E., MacGregor, E., Vorster, N. H., Levitt, N. S. & Steyn, K. Partial replacement of NaCl can be achieved with potassium, magnesium and calcium salts in brown bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 58(7), 508–521 (2007).

Charlton, K. The development of a dietary intervention to modify cation content of foods and the evaluation of its effects on blood pressure in hypertensive Black South Africans [Ph.D. Thesis]. University of Cape Town, South Africa. (2006).

Abdul Aziz, N. S. et al. Risk factors related with high sodium intake among Malaysian adults: findings from the Malaysian community salt survey (MyCoSS) 2017–2018. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 40(Suppl 1), 14 (2021).

Institute for Public Health. Population-based salt intake survey to support the national salt reduction programme for Malaysia (Malaysian Community Salt Survey-MyCoSS). (2019).

Faizi Faizul, Q. A., Shahar, S., Harun, Z. & Haron, H. Survey on the salt usage among fish cracker (Keropok lekor) manufacturers in several districts of Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia. Malays Appl. Biol. 53(3), 71–82 (2024).

Charlton, K. E. et al. Compliance of the food industry with mandated salt target levels in South Africa: towards development of a monitoring and surveillance framework. J. Food Compos. Anal. 126(3), 105908 (2024).

Allemandi, L., Tiscornia, M., Guarnieri, L., Castronuovo, L. & Martins, E. Monitoring sodium content in processed foods in Argentina 2017–2018: Compliance with national legislation and regional targets. Nutrients. ;11(7). (2019).

Food Standards Agency. UK salt reduction targets for 2017. (2017). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a75653fe5274a1baf95e3d6/Salt_reduction_targets_for_2017.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2024.

World Health Organization. WHO global sodium benchmarks for different food categories. (2021). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025097. Accessed 20 Apr 2024.

World Health Organization. WHO South-East Asia Region Sodium Benchmarks for Packaged Foods. (2023). https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375596/9789290210818-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 22 Oct 2024.

Australian Division of World Action on Salt and Health. Interim Australian targets for sodium levels in 85 food categories. (2011). https://issuu.com/emmastirling/docs/interim_salt_targets_for_australia. Accessed 20 Apr 2024.

The New York City Department Of Health and Mental Hygiene. National salt reduction initiative. www.MenuStat.org. Accessed 20 Apr 2024. (2014).

Allemandi, L. et al. Sodium content in processed foods in Argentina compliance with the National law. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 5, 197–206 (2015).

Ashford, R. et al. Assessment of salt intake from urinary sodium in adults (aged 19 to 64 years) in England, 2018 to 2019. National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Public Health England, London. (2020). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e7cd9cdd3bf7f133ed1b6a1/Report_England_Sodium_Survey_2018-to-2019__3_.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2024.

Dunford, E. et al. The variability of reported salt levels in fast foods across six countries: opportunities for salt reduction. CMAJ 184(9), 1023 (2012).

Webster, J. L., Dunford, E. K. & Neal, B. C. A systematic survey of the sodium contents of processed foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91(2), 413–420 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Mrs. Yen Nee Tan, Mrs Kasumawaty Sudin, Mrs. Rosmaniza Abd Samad and Dr. Norlen Mohamed from MOH by providing valuable inputs throughout the process of establishing the maximum salt targets. We would also like to thank the research team led by Prof Datin Dr Chia Yook Chin for providing market survey data on instant noodles, which contributed to our instant noodles databese. Also, special thanks to the fieldworkers in assisting in market survey.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Resolve to Save Lives (NN-2024-021). Resolve to Save Lives is funded by grants from Bloomberg Philanthropies; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and Gates Philanthropy Partners, which is funded with support from the Chan Zuckerberg Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have participated in the process of establishing maximum salt targets. YQO prepared the manuscript under supervision of SS. All authors have read, edited and approved the final draft of this manuscript by providing critical revision of the manuscript for optimum intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SP-R is employee of Consensus Action on Salt, Sugar & Health (CASSH), a non-profit charitable organization. FJH is an unpaid member of Action on Salt and World Action on Salt, Sugar and Health (WASSH). GAM is the unpaid chairman of Action on Salt, and WASSH. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, Y.Q., Shahar, S., Haron, H. et al. Strengthening salt reduction policy for Malaysia through proposed maximum salt targets of selected processed food groups. Sci Rep 15, 17385 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00296-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00296-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Reformulation of soy sauce to reduce sodium content and assessment of manufacturer readiness, consumer acceptance, and shelf life

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Survey on the availability, labeling, and pricing of salt-free/reduced packaged foods and table salt alternatives in Klang Valley, Malaysia

Discover Food (2025)