Abstract

Dentists encounter a variety of occupational hazards in the practice of dentistry, with the potential to impact their general well-being and the quality of service provided to patients. This study aimed to validate an instrument for measuring the perception of occupational safety and health among Peruvian dentists. This was an instrumental study in which 379 Peruvian dentists participated. The instrument on the perception of occupational safety and health in dentists was adapted and validated using the NTP 182 (Self-assessment survey of working conditions) as a reference. Content validity was assessed by means of the Aiken V. The internal structure was assessed by exploratory factor analysis (EFA), principal component analysis (PCA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The internal consistency of the instrument was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha. The content analysis by expert judges supports the representativeness of the items related to the construct. Four dimensions were established by means of the EFA, PCA and CFA: work demands and well-being, ergonomics and physical conditions of the environment, safety and risk prevention, and working conditions and worker protection. Regarding the AFC, adequate fit indices were evidenced: Chi-square (χ2) = 321.071, degrees of freedom (df) = 206, χ2/df = 1.559 (p < 0.001), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.047, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.974, Tucker and Lewis index (TLI) = 0.963, weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) = 0.045 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.038. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha was very good (α = 0.846). The simplified questionnaire to assess dentists’ perceptions of occupational safety and health has been demonstrated to be both valid and reliable. Its utilization for research purposes is recommended, with a focus on the following four dimensions: work demands and well-being, ergonomics and physical conditions of the environment, safety and risk prevention, and working conditions and worker protection. To ensure the validity of the findings, it is advised that the questionnaire be administered to a larger sample in a range of social and geographical contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) is considered an inalienable right of all workers whose purpose is to prevent accidents and occupational diseases in the workplace. Therefore, organizations must implement measures to enhance working conditions with a view to avoiding physical and psychological problems among workers1.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that approximately 317 million people worldwide experience occupational accidents annually, with 2.34 million fatalities resulting from occupational accidents or diseases2. This shows that safety and health issues at work happen a lot, and they’re much worse in developing countries. This is because many workers can be physically and mentally hurt by being exposed to different risks at work, which can have personal, family, and social effects3.

However, significant progress has been made in the field of occupational safety and health due to the existence of laws, directives, decrees, and guidelines adopted by various countries to regulate the issue. Nevertheless, the absence of clearly delineated and standardized roles for diverse professional categories remains a salient concern4. The laws in Peru that cover health and safety at work are set out in Law No. 29,783 and the rules that go with it, which were made official by Decree No. 005-2012-TR. This legislative apparatus is applicable to all services and economic sectors, as well as to all employers and public servants nationwide1.

An occupational hazard is defined as an injury or ailment resulting from work or the work environment, which can result in trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), loss of dignity, anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, low self-esteem, lack of trust in people, aging, loss of autonomy, absenteeism, physical injuries, musculoskeletal disorders, among others3,5,6. Research indicates that the primary biological hazards to which health professionals are exposed are needlestick injuries, affecting 80% of workers, and exposure to contaminated substances, present in 75% of cases. With regard to non-biological risks, the most prevalent are back pain, affecting 79% of professionals, and overtime, affecting 72% of them3,7.

Occupational safety and health are pivotal to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as it relates directly to several of its goals, in particular the 3rd Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), which aims to reduce pollution-related mortality; the 8th SDG, which promotes labor rights in safe environments; and the 16th SDG, which calls for effective and transparent institutions8. These goals underscore the imperative to establish safe working conditions as an integral component of sustainable development8.

Dentistry is widely regarded as a high-risk profession. This is due to the exposure of dentists to a variety of harmful factors, including radiation, percutaneous exposure incidents, exposure to dental materials, noise and vibrations, as well as allergic problems, vision problems, musculoskeletal disorders, occupational violence, and sedentary work9,10,11,12. Furthermore, in comparison with other health professionals, dentists are in constant contact with patients and utilize high-speed rotating instruments, which generate contaminated bioaerosols and expose them to various infectious diseases3,10,13. Conversely, stress arising from interactions with patients, daily routine, and compliance with stringent healthcare procedures contributes to the development of psychological problems, thus classifying them as one of the most susceptible work groups in healthcare3,10,13. It is therefore vital to recognize, monitor, and properly manage occupational risks in order to mitigate their consequences3,13.

A literature review reveals the existence of some validated instruments related to occupational safety and health for dentists. One such instrument is the Interdisciplinary Worker Health Approach Instrument (IWHAI), which, as its name suggests, is interdisciplinary in approach and not exclusively designed for dentists, but rather for the general assessment of health aspects14. In contrast, Garcia’s study15 utilized the Nordic Workplace Safety Questionnaire to assess dental center workers’ perceptions of safety in their work environment. However, this questionnaire primarily focuses on employees’ perceptions of general safety management policies and practices, neglecting to address the specific risks and health-related aspects that are pertinent to dentists. Furthermore, the study by Ramaswami et al.16 utilized a validated questionnaire to evaluate knowledge regarding risks and preventive measures; however, it did not assess workers’ perceptions of safety and health in their workplace. Finally, the research by Reddy et al.17 employed a validated questionnaire to assess dentists’ perceptions of occupational hazards and preventive measures. Nevertheless, it did not encompass significant aspects of physical environmental conditions and work demands that may influence dentists’ health.

It is imperative that companies or organizations adhere to the prevailing protocols concerning occupational safety and health. The repercussions of occupational diseases and accidents on the lives of workers are manifold, encompassing not only human suffering for employees and their families but also substantial economic losses for organizations. These losses manifest in the form of elevated healthcare expenditures, compensation costs, diminished production, productivity, and reduced work participation2. This study aimed to validate an instrument for measuring the perception of occupational safety and health among Peruvian dentists.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The present study respected the bioethical principles of confidentiality, freedom, justice, respect and non-maleficence set out in the Declaration of Helsinki18. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Dentistry of the Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal with opinion number 006-2024-COMITE-DE-ETICA dated 13 March 2024. In addition, participants gave their voluntary informed consent on the first page of the questionnaire.

Study design

An analytical, prospective, observational, cross-sectional, analytical study with instrumental design was conducted. The manuscript was written according to the guidelines of strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE)19.

Sample size and participant selection

The study was conducted in the Peruvian capital between July and November 2024. The population consisted of 24,856 dentists in the Peruvian capital. The minimum sample size was calculated on the basis of Lloret-Segura et al.20, who recommended a minimum sample size of 200 cases, even under optimal conditions of high communalities and well-determined factors to perform exploratory factor analysis. Therefore, in Epidat 4.2 (N = 24,856), a formula for estimating a proportion with a finite population was taken into account, considering a significance level (α) = 0.05, a precision error of 5% and p = 0.5; therefore, we worked with a sample size of 379 participants (n = 379). Purposive sampling was used, which facilitated the selection of participants and allowed for more agile and efficient data collection.

Inclusion criteria.

-

Dentists who voluntarily give their informed consent.

-

Dentists affiliated to the Lima Dental Association.

-

General and specialist dentists.

-

Dentists who work in at least one establishment and report to a chief.

Exclusion criteria.

-

Dentists who did not complete the questionnaire.

Instrument preparation

The instrument for measuring the perception of occupational safety and health in dentists was adapted from Nogareda’s NTP 182 (Self-assessment survey of working conditions)21. This questionnaire in its original form was divided into 8 dimensions: D1 (Safety conditions), D2 (Environmental pollutants), D3 (Working environment), D4 (Job requirements), D5 (Work organization), D6 (Organization of prevention). D7 (Personal protection) and D8 (Warning symptoms) with a total of 188 items with Yes / No / Don’t know. Scoring was 1 point (correct) and 0 (incorrect). Sociodemographic characteristics of the dentists (age, gender, origin, marital status, academic degree and years of professional experience) were also included in the questionnaire.

Procedure

The content of the questionnaire was reviewed and adapted by three experts in the field of dental research and validated by five experts with more than 15 years of professional experience (two researchers with a doctoral degree in public health, one researcher with a doctoral degree in education, one statistician, and one master’s degree in dentistry). Expert judgement carried out the validation in two stages. In the first stage, the experts indicated that the instrument could be applicable once the relevant corrections had been made to the observations made; after these observations were made, a first version of the instrument was obtained, divided into 7 dimensions: D1 (Safety conditions), D2 (Environmental conditions), D3 (Job requirements), D4 (Work organization), D5 (Prevention and health), D6 (Personal protection), and D7 (Warning symptoms), with a total of 114 items [see supplementary material]. Subsequently, in the second stage, the experts, in accordance with the Cosmin Guide22, carried out a validation for each item considering the criteria of relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility.

The questionnaire on the perception of occupational safety and health in dentists was transferred to Google Form® and distributed using the self-administered survey technique by means of a link via social networks, WhatsApp® and e-mails of the registered dentists in the Peruvian capital. Participants were automatically directed to the objective of the research and to the informed consent page by clicking on the link. Once they accepted, they were directed to the questionnaire with the instructions for completing it. Participants were free to opt out of the study at any point. Personal data such as name, telephone number, and address were not requested. The study was designed to be a one-time survey. Data were collected and stored in a Microsoft® Excel 2019 spreadsheet and stored in a password-protected digital folder to which only the principal investigator had access. To avoid duplication of participation, participants were asked to initial their name along with their age (e.g., MILC42). The statistical package SPSS v.24.0 and the software Factor Analysis were used for data analysis.

Statistical analysis

In order to ascertain content validity, the items were subjected to evaluation by five expert judges. The scores thus obtained were then used to calculate Aiken’s V coefficient, together with its 95% confidence interval, in accordance with the criteria of relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility. In this way, the critical point of Aiken’s V = 0.5 was taken into consideration22.

In order to validate the construct, a descriptive analysis was conducted in order to calculate the mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis of the questionnaire items. The value ± 1.5 was considered for skewness and kurtosis. In addition, item-total response was assessed using tetrachoric correlation, as the responses to the questions were dichotomous23. Subsequently, an EFA was performed on the instrument, with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of adequacy (KMO > 0.5) and Bartlett’s sphericity (p < 0.05) being considered acceptable. The number of dimensions of the questionnaire was determined according to principal component analysis in order to group and reduce the items24,25, after verification of the multivariate normality assumption (Mardia kurtosis).

CFA was then carried out, with parallel analysis of the variance explained by the items and the goodness of fit indices, e.g. χ2 (adjusted robust chi-square), WRMR, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. The reliability of the questionnaire as a whole and of each of its dimensions was then analysed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Results

Of the total number of participants, 52.5% were women, and 78.4% were originally from the Peruvian capital. In addition, the majority, 59.1%, were single. On the other hand, 52% were professional dentists with only a bachelor’s degree. Finally, the mean years of experience was 14.4 ± 13.2 years, and the mean age was 41.5 ± 14.5 years (Table 1).

For the evaluation of the 114 items, the critical point of Aiken’s V (V) = 0.5 was considered. To eliminate an item, it was taken into account that the confidence interval does not contain such a critical value26. Therefore, after the evaluation of the five experiential judges, no item was removed, as the confidence interval did not pass the critical value according to the criteria of relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility22 (Table 2).

For the EFA, the skewness and kurtosis of the 114 items were calculated so that items with skewness and kurtosis > 1.5 had to be eliminated27. According to the excess of the skewness range, items 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 11, 14, 18, 18, 25, 25, 30, 30, 31, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 46, 49, 50, 52, 55, 57, 59, 63, 68, 69, 70, 71, 76, 77, 81, 85, 99, 104, 105, 112 were eliminated. Then, according to the excess of the kurtosis range, items 3, 9, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 44, 54, 60, 65, 72, 80, 82, 83, 86, 89, 90, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 98, 100, 101, 102, 103, 107, 1113, 114 were eliminated (Table 3).

After eliminating items according to excess skewness and kurtosis, 38 items remained. On the other hand, it was verified that the items did not meet the requirement of multivariate normality according to Mardia’s kurtosis = 1450.72 (p < 0.001), so instead of using Pearson’s correlation for the item-total correlation28, it was decided to use the tetrachoric correlation. Furthermore, this correlation is appropriate when item responses are dichotomous23. Then, according to the item-total tetrachoric correlation, those values that were < 0.3020 were eliminated, so items 108, 109, 110, and 111 were removed, leaving 34 items. Next, the communality of each remaining item was calculated, so it was decided to remove items 29, 43, 78, and 88, since they presented values lower than the minimum required (h2 = 0.30)20, leaving the questionnaire with 30 items (Table 4).

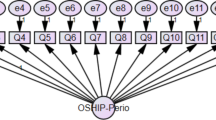

The internal structure validity test yielded a KMO measure of 0.829, which was considered to be satisfactory. Furthermore, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was found to be significant (p < 0.001) for the questionnaire comprising all 30 items. Conversely, the parallel analysis based on principal components indicated the extraction of four factors that explained 42.3% of the variance. However, given that the multivariate normality of kurtosis was not met, and in order to group and reduce the number of items24,25, the factor extraction method PCA was chosen. This resulted in the elimination of factor loadings lower than 0.4 (items 19, 34, 75, 84, and 87), leaving 25 items. Furthermore, as the correlations between factors were found to be low (< 0.4), it can be deduced that there was no multicollinearity29,30, thereby ensuring that the dimensions formed do not depend on a higher factor (Table 5).

For the final 25-item questionnaire [see supplementary material], the parallel analysis was re-run and it was confirmed that it would be appropriate to consider four factors explaining 45.4% of the variance (Table 6).

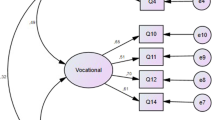

The CFA showed adequate fit indices: Chi-square (χ2) = 321.071, df = 206, χ2/df = 1.559 (p < 0.001), SRMR = 0.047 (acceptable < 0. 08), CFI = 0.974 (good > 0.9), TLI = 0.963 (good > 0.9), WRMR = 0.045 (good fit < 1.0) and RMSEA = 0.038 (90% CI = 0.010–0.050)31.

Regarding the reliability of the overall instrument, Cronbach’s α was 0.846 (excellent), and according to its four dimensions, Cronbach’s α was 0.797, 0.773, 0.666, and 0.628, respectively, being these values acceptable.

Discussion

The current literature identifies several instruments developed for evaluating occupational health and safety in dentists14,15,16,17. However, it is important to note that one of the instruments is interdisciplinary and not exclusively designed for dentists14, another does not address profession-specific risks or health-related aspects15, another assesses knowledge rather than the perception of risks and preventive measures16, and the last one omits important aspects, such as the physical conditions of the environment and work demands17,32. Consequently, this study aimed to validate an instrument for measuring the perception of occupational safety and health among Peruvian dentists.

The original instrument comprised 188 items, which were divided into eight dimensions21. Subsequently, an item-by‐item validation was undertaken in accordance with the COSMIN guidelines22, with particular attention given to the relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility of the 114 items. However, following a thorough evaluation, it was determined that no items required removal. Whilst these findings reinforced the content validity of the instrument and ensured that each item contributed significantly to the intended measurement, it is important to note that the Aiken V focuses solely on content validity; consequently, other forms of validation are essential for a comprehensive evaluation of the instrument26.

In accordance with methodological recommendations to prevent such extreme values from distorting the interpretation of the underlying factor structure, 76 items with skewness and kurtosis values higher than 1.5 were eliminated during the exploratory factor analysis33,34,35. High kurtosis is indicative of heavy tails in the data distribution, which can result in over or underestimation of factor loadings by assigning excessive weight to extreme values, thereby compromising the stability and validity of the factor model34. Similarly, high skewness indicates a substantial deviation from normality which complicates the accurate extraction of factors and the representation of latent dimensions35. Consequently, it was essential to remove these items to ensure that the analysis accurately reflects the underlying construct and to guarantee the integrity and robustness of the measurement instrument. Furthermore, such deviations from normality may lead to either an underestimation or an overestimation of factor loadings, making it challenging to accurately identify the latent dimensions. Accordingly, we employed analytical methods designed specifically for categorical items such as tetrachoric correlations, which align with the inherent distribution of dichotomous items and facilitate a more precise interpretation of the model36. Therefore, for the item total correlation, we opted to use tetrachoric correlations23 instead of Pearson’s correlation, which is appropriate for normally distributed items, eliminating items with values below 0.30 and retaining a total of 34 items. This approach minimizes distortions and ensures a more robust and reliable assessment of the questionnaire’s internal structure and psychometric validity23. Furthermore, the communality of each remaining item was calculated, and it was decided to remove 4 items as they had scores lower than the minimum required, indicating that the items did not contribute adequately to the construct being measured, so that only items that provided relevant information were retained20,37.

The KMO measure was adequate enough for the internal structure validity test. This means that the data can be used for factor analysis and that the questionnaire items are significantly linked to each other. It also found the Bartlett’s test of sphericity significant for the questionnaire containing all 30 items. This indicated that the item correlations are significantly different from zero and that a latent structure can be explored. This supports the suitability of the questionnaire to measure the proposed theoretical construct20,38. Moreover, the parallel analysis of the items indicated that it would be expedient to extract four factors that explained 42.3% of the variance, signifying that the four identified factors represent the most salient underlying dimensions in the data, thereby providing a simplified and understandable structure for further interpretation and analysis20,38. However, the multivariate normality of kurtosis wasn’t met, so PCA was used. Items with factor loadings of less than 0.4 were thrown out, leaving only 25 items that were representative. The loadings indicated that the items exhibited a weak relationship with the extracted factors, suggesting that they did not contribute significantly to the representation of the theoretical construct. Meanwhile, low inter-factor correlations (< 0.4) indicated the absence of multicollinearity, suggesting that the dimensions formed were independent and reflected distinct constructs without relying on a common underlying factor29,39. The final 25-item questionnaire was subjected to parallel principal component analysis, which confirmed that it would be appropriate to consider four factors explaining 45.4% of the variance. This finding suggests that a substantial proportion of the variability in responses can be attributed to these four factors, thereby validating their relevance in measuring the proposed theoretical construct40.

The CFA demonstrated adequate fit indices, thereby indicating that the proposed model reasonably fits the observed data and possesses sufficient flexibility to accommodate it without overfitting. This is imperative to ensure the validity and reliability of the inferences and conclusions derived from the analysis41. Furthermore, we observed an acceptable SRMR, which indicates minimal discrepancies between the observed covariances and the model predictions. Additionally, we identified a favorable CFI, indicating a robust model fit compared to a null model, thus validating the model41. It was found that the TLI worked well, which means that the model can clearly show the variance and covariance of the data. This observation suggests that the instrument is reliable and valid for quantifying the variables of interest. Finally, a WRMR and RMSEA were found to be low. These results show a good fit, which means that the model is good enough to show how the population’s covariance structure works. This makes us more confident in the proposed model’s validity41.

Concerning the reliability of the overall instrument, Cronbach’s α was determined to be 0.846, classifying it as excellent. For its four dimensions, Cronbach’s α was recorded as 0.797, 0.773, 0.666, and 0.628, respectively, which are considered acceptable values. According to these results, the instrument’s internal consistency is good enough for each dimension to be used in research. The instrument as a whole is good for measuring the concept being studied and gathering data in different areas of professional dental practice42. Although the Cronbach’s alpha value was slightly lower than 0.7 in the third and fourth dimensions of the present instrument, this can be considered justifiable, given the complexity or multidimensionality of the construct assessed. In this sense, the interpretation of alpha should be framed within the theoretical and empirical context of the construct43,44. Furthermore, in dimensions with few dichotomous items, the alpha value may be lower, as dichotomous responses tend to have less variability, which slightly reduces the internal consistency of these dimensions. This is because dichotomous items limit variability compared to Likert-type items44,45.

The research’s most significant contribution is the simplification of a general instrument for safety at work in the dental field. The original NTP-182 quiz had 188 questions spread out over eight dimensions. The simplified version has just 25 questions spread out over four dimensions: F1 (work demands and well-being), F2 (ergonomics and physical conditions of the environment), F3 (safety and risk prevention), and F4 (working conditions and worker protection). The dimensions of this new version have been reformulated according to the content of the items and the literature related to dentistry, offering a simplified version of the instrument while preserving the validity of the questionnaire by including representative items, thus ensuring the relevance of the questions. In addition, it improved the psychometric properties by increasing reliability and validity after the removal of irrelevant items46. It also reduces the time needed and improves comprehension for the development and application of the questionnaire, thus facilitating its use in time-critical situations with a more agile interpretation of the results47. Dimension F1 (work demands and well-being) assesses how work demands impact employees’ health, including adequate sleep, recovery from fatigue, sufficient breaks, flexibility in work rhythm and schedule, as well as the possibility of short absences48. The F2 dimension (ergonomics and physical conditions of the environment) is concerned with the prevention of injuries through the adequate design of the workspace. This includes the adequate protection of cables and plugs, as well as the necessary safety measures for the use of electrical instruments. It also covers aspects such as the lighting and temperature of the workspace, the maintenance of clean and disinfected areas, and the availability of ergonomic seating that ensures sufficient space to vary the position of the legs and perform the work comfortably49,50. Dimension F3 (safety and risk prevention) emphasizes the establishment of protocols and safety measures that minimize occupational risks. Such measures include the evaluation of warning signs for hazards, the availability of fire-fighting equipment such as fire extinguishers and hoses, the existence of rules for the handling and transport of dental materials and supplies, and regular equipment checks and consultation with staff in occupational decisions9,51. Finally, dimension F4 (working conditions and worker protection) assesses a fair and safe working environment, which includes the existence of adequate spaces for handling chemical supplies, the availability of staff trained in first aid, and the presence of posters indicating the mandatory use of personal protective equipment (PPE)52. The present 25-item instrument has been designed to facilitate a rapid diagnosis of the occupational safety and health situation, thereby encouraging greater staff participation. The results obtained from this study will facilitate dentists’ understanding of the risks associated with their practice, thus fostering a culture of self-care and responsibility that will, in turn, improve their health and, consequently, the quality of service provided to patients32.

Among the limitations of the present study, a stability analysis of the instrument was not performed, as it was not possible to measure the precision and accuracy of the instrument over time in various contexts. In addition, the survey was conducted virtually, as the geographical extension of Metropolitan Lima made it difficult to access dentists in person according to their available schedules. It is imperative to acknowledge the inherent limitations of virtual administration, including reduced participation and the potential for item misinterpretation due to the absence of direct interaction. Consequently, subsequent pilot testing or cognitive interviews will be essential for identifying and resolving any potential issues with online administration. Another limitation was that the present study was conducted only in the Peruvian capital. Nevertheless, the study provides a basis for further research to validate or improve the applicability of the instrument in various contexts and geographic regions. It is important to recognise that the process of validating an instrument is a continuous one, as it is not feasible to assess all psychometric properties for every aspect of validity and reliability in all potential applications.

In view of the findings, it is recommended that future research should investigate convergent validity when comparing this instrument with others that measure analogous constructs, and discriminant validity when comparing this instrument with others that measure constructs unrelated to the construct of interest in this study. In addition, it is recommended that structural invariance between genders be assessed. Additionally, it is recommended to test and retest this questionnaire by altering the order of the questions on two separate occasions and to evaluate the concordance of the scores53. It is recommended that the scope of the questionnaire be expanded to include dimensions such as work-life balance, institutional policies, and socioeconomic influences, as these may indirectly affect perceptions of occupational safety and health, thereby enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of the construct. Therefore, it is recommended that qualitative methods (e.g. interviews, focus groups) be incorporated to complement and contextualize the quantitative findings. This broader approach would facilitate a more comprehensive evaluation of the underlying construct and potentially enhance the instrument’s explanatory power in terms of variance54,55. Finally, to effectively implement an occupational safety and health measurement instrument in dental practice and enhance workplace safety standards, it is recommended that professional associations incorporate it into routine safety audits and training programs. The data collected should be used to identify critical areas for improvement and to design interventions that address the identified risks. In addition, establishing a continuous monitoring system will facilitate tracking changes over time and adjusting safety protocols in response to new challenges. This approach will foster a culture of continuous improvement in occupational safety and health within dental practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, recognizing the limitations of the present study, the simplified questionnaire to assess dentists’ perceptions of occupational safety and health has been demonstrated to be both valid and reliable. Its utilization for research purposes is recommended, with a focus on the following four dimensions: work demands and well-being, ergonomics and physical conditions of the environment, safety and risk prevention, and working conditions and worker protection. To ensure the validity of the findings, it is advised that the questionnaire be administered to a larger sample in a range of social and geographical contexts.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for Measuring INstruments

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- ILO:

-

International Labour Organization

- IWHAI:

-

Interdisciplinary Worker Health Approach Instrument

- OSH:

-

Occupational Safety and Health

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- URSULA:

-

Union of Latin American University Social Responsibility

- USR:

-

University Social Responsibility

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

- TLI:

-

Tucker and Lewis index

- WRMR:

-

Weighted root mean square residual

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

References

Autoridad Nacional del Servicio Civil. Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo (SST) en el sector público. [Accessed Apr 25, 2024]. (2024). Available from: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/servir/campa%C3%B1as/14946-seguridad-y-salud-en-el-trabajo-sst-en-el-sector-publico.

Organización Internacional del Trabajo. Fomentar el diálogo Social para una cultura de seguridad y salud. [Accessed Apr 25, 2024]. (2022). Available from: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_842509.pdf.

AlDhaen, E. Awareness of occupational health hazards and occupational stress among dental care professionals: evidence from the GCC region. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.922748 (2022).

Akpinar-Elci, M. et al. Assessment of current occupational safety and health regulations and legislation in the Caribbean. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica. 41, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2017.26 (2017).

Anderson, G. S., Di Nota, P. M., Groll, D. & Carleton, R. N. Peer support and Crisis-Focused psychological interventions designed to mitigate Post-Traumatic stress injuries among public safety and frontline healthcare personnel: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (20), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207645 (2020).

Petereit-Haack, G., Bolm-Audorff, U., Romero Starke, K. & Seidler, A. Occupational risk for Post-Traumatic stress disorder and Trauma-Related depression: A systematic review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (24), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249369 (2020).

Bin-Ghouth, A. S. et al. Occupational Hazards among Health Workers in Hospitals of Mukalla City, Yemen. J Community Med Health Care. ; 6(1):1–5. [Accessed May 21, 2024]. (2021). Available from: https://austinpublishinggroup.com/community-medicine/fulltext/jcmhc-v6-id1045.php

Organización Internacional del Trabajo. Metas de los ODS pertinentes vinculados con la seguridad y la salud en el lugar de trabajo.2024.[Accessed May 28, 2024]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/dw4sd/themes/osh/WCMS_620646/lang--es/index.htm.

Alamri, A., ElSharkawy, M. F. & Alafandi, D. Occupational physical hazards and safety practices at dental clinics. Eur. J. Dent. 17 (2), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1745769 (2023).

Federation Dental International. Health and safety in the dental workplace. 2021.[Accessed May 30, 2024] Available from: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/hsdw.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Dentistry. [Accessed Jun 10, 2024] (2024). Available from: https://www.osha.gov/dentistry.

Vázquez-Alcaraz, S., Rodríguez-Soto, M. C., Monroy-Salcedo, R. A. & Cárdenas-Delgado, R. K. Development and validation of an instrument to assess adherence to occupational health protocols in dentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 85(3), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12454 (2021).

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hazard Recognition, Control and Prevention. [Accessed Jun 25, 2024] (2024). Available from: https://www.osha.gov/dentistry/hazard-control-prevention

Viterbo, L. M. F., Dinis, M. A. P., Costa, A. S. & Vidal, D. G. Development and validation of an interdisciplinary worker’s health approach instrument (IWHAI). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (15), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152803 (2019).

García, S. & Percepción de la seguridad y salud en el trabajo en una población perteneciente a 11 clínicas odontológicas particulares de Bogotá, D.C,2016. [DDS thesis]. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario Colombia; (2016). https://doi.org/10.48713/10336_12743.

Ramaswami, E. et al. Assessment of occupational hazards among dentists practicing in Mumbai. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 9 (4), 2016–2021. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1180_19 (2020).

Reddy, V., Bennadi, D., Satish, G. & Kura, U. Occupational hazards among dentists: A descriptive study. J. Oral Hyg. Health. 3 (5), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-0702.1000185 (2015).

World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. JAMA 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.21972 (2024).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63 (7), 737–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 (2010).

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A. & Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de Los ítems: Una Guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. psicol. 30 (3), 1151–1169. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361 (2014).

Nogareda, C. N. T. P. 182:Encuesta de autovaloración de las condiciones de trabajo.1986.[Accessed Jun 28, 2024]. Available from: https://www.insst.es/documentacion/colecciones-tecnicas/ntp-notas-tecnicas-de-prevencion/5-serie-ntp-numeros-156-a-190-ano-1986/ntp-182-encuesta-de-autovaloracion-de-las-condiciones-de-trabajo.

Mokkink, L. B. et al. COSMIN Study Design checklist for Patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. [Accessed Jun 28, 2024]. (2019). Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf

El-Hashash, E. F. & El-Absy, K. M. Methods for determining the tetrachoric correlation coefficient for binary variables. Asian J. Prob Stat. 2 (3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajpas/2018/v2i328782 (2018).

Hamed Taherdoost, S., Sahibuddin, N. & Jalaliyoon Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Jerzy Balicki. Adv. Appl. Pure Math. 27, 375–382 (2014). https://hal.science/hal-02557344v1

Williams, B., Onsman, A. & Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A Five-Step guide for novices. Australasian J. Paramedicine. 8, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.8.3.93 (2010).

Penfield, R. D. & Giacobbi, P. R. Applying a score confidence interval to Aiken’s item content-relevance index. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 8 (4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327841mpee0804_3 (2004).

Pérez, E. R. & Medrano, L. Análisis factorial exploratorio: bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Rev Argentina Cienc Comport (RACC). ;2(1):58–66. [Accessed Jun 28, 2024]. (2010). Available from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3161108.

Muthen, B. & Kaplan D A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal likert variables: A note on the size of the model. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 45 (1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1992.tb00975.x (1992).

Mason, C. H. & Perreault, W. D. Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. J. Mark. Res. 28 (3), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379102800302 (1991).

Eignor, D. R. The standards for educational and psychological testing. APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology 2013; 1. Test theory and testing and assessment in industrial and organizational psychology: 245–50.https://doi.org/10.1037/14047-013.

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ Model. 6 (1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Yasaswi, C. S. N. et al. Occupational hazards in dentistry and preventing them. Int. J. Med. Rev. 5 (2), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.29252/IJMR-050204 (2018).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. & Tatham, R. L. Multivariate Data Analysis 7th edn (Pearson, 2010).

Wulandari, D., Sutrisno, S. & Nirwana, M. B. Mardia’s skewness and kurtosis for assessing normality assumption in multivariate regression. Enthusiastic 1 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.20885/enthusiastic.vol1.iss1.art1 (2021).

Hanusz, Z., Tarasińska, J. & Osypiuk, Z. On the small sample properties of variants of Mardia’s and Srivastava’s kurtosis-based tests for multivariate normality. Biometrical Lett. 49 (2), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.2478/bile-2013-0012 (2012).

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. E. & Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM Estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods. 17 (3), 354–373 (2012).

Costello, A. B. & Osborne, J. W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. PARE 10 (7), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868 (2005).

Ferrando, P. J., & Anguiano-Carrasco, C. El análisis factorial Como técnica de investigación En psicología. Pap Psicol. 31 (1), 18–33 (2010). https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/778/77812441003.pdf [Accessed Jul 2, 2024]. Available from: .

Rios, J. & Wells, C. Validity evidence based on internal structure. Psicothema 26 (1), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.260 (2014).

Crawford, A. V. et al. Evaluation of parallel analysis methods for determining the number of factors. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 70 (6), 885–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164410379332 (2010).

Morata-Ramírez, M. A., Holgado, F. P. & Barbero-GarcíaMI, Méndez, G. Confirmatory factor analysis. Recommendations for unweighted least squares method related to Chi-Square and RMSEA. Acción Psicol. 12 (1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.5944/ap.12.1.14362 (2015).

Taber, K. S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 48, 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 (2018).

Nunnally, J. C. & Bernstein, I. H. Psychometric Theory 3rd edn (McGraw-Hill, 1994).

DeVellis, R. F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications 3rd edn (Sage, 2012).

Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55 (2011).

Chukwu, S. & Chidinma, I. Psychometric properties of a test. Overv. 5 (2), 2217. https://doi.org/10.55248/gengpi.5.0224.0539 (2024).

Sharma, H. How short or long should be a questionnaire for any research? Researchers dilemma in deciding the appropriate questionnaire length. Saudi J. Anaesth. 16 (1), 65–68. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.sja_163_21 (2022).

Olivera-Arones, E., Mattos-Vela, M. A., Evaristo-Chiyong, T. A. & Tuesta-Orbe, L. V. General occupational Well-being of dentists working in the ministry of health and regional governments of Peru during the COVID-19 pandemic. Iatreia 37 (3), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iatreia.229 (2023).

Quinzo, F. Ergonomía En La práctica odontológica. Cienc. Lat. 7 (3), 2396–2305. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v7i3.6355 (2023).

Pasha, Z., Prasanna, P. S., Kshirsagar, J. S., Shenoy, S. & Shah, R. R. Unlocking the potential of ergonomics in dentistry: current insights and future directions: A review. J. Dent. Panacea. 5 (3), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.jdp.2023.025 (2023).

Choi, E. M., Mun, S. J., Chung, W. G. & Noh, H. J. Relationships between dental hygienists’ work environment and patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4136-8 (2019).

Goetz, K., Schuldei, R. & Steinhäuser, J. Working conditions, job satisfaction and challenging encounters in dentistry: a cross-sectional study. Int. Dent. J. 69 (1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12414 (2019).

Cayo-Rojas, C. F. et al. Psychometric evidence of a perception scale about covid-19 vaccination process in Peruvian dentists: a preliminary validation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22 (1), 1296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08677-w (2022).

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A. & Creswell, J. W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 48 (6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117 (2013).

Palinkas, L. A. et al. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment Health. 38 (1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the School of Stomatology of the Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista and the Faculty of Dentistry of the Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal for their constant support in the development of this research.

Funding

Self-financed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.C. and C.C.R conceived the research idea; M.L.C., M.C.R., J.C.B., and C.C.R elaborated the manuscript; M.L.C., J.C.B., J.E.D. and A.C.P., collected and tabulated the information; M.L.C., J.C.B., M.C.R., A.C.P., C.L.G., and C.C.R. carried out the bibliographic search; C.C.R. interpreted the statistical results; M.L.C., M.C.R., C.L.G., and C.C.R. helped in the development from the discussion; M.L.C., A.C.P, C.L.G., M.C.R., J.E.D., and C.C.R. performed the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic approval and consent to participate

The present study respected the bioethical principles of confidentiality, freedom, justice, respect and non-maleficence set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Dentistry of the Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal with opinion number 006-2024-COMITE-DE-ETICA dated 13 March 2024. In addition, participants gave their voluntary informed consent on the first page of the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ladera-Castañeda, M., Escobedo-Dios, J., Cornejo-Pinto, A. et al. Validation of an instrument to measure the perception of occupational safety and health among Peruvian dentists. Sci Rep 15, 15357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00395-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00395-7