Abstract

The forecasting of a patient’s response to radiotherapy and the likelihood of experiencing harmful long-term health impacts would considerably enhance individual treatment plans. Due to the continuous exposure to radiation, cardiovascular disease and pulmonary fibrosis might occur. For forecasting the response of patients to chemotherapy, the Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) technique is widely used. With the help of radiotherapy, cancer diseases are diagnosed, but some patients suffer from side effects. The toxicity of radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be estimated. For validating the patient’s improvement in treatments, a patient response prediction system is essential. In this paper, a Deep Learning (DL) based patient response prediction system is developed to effectively predict the response of patients, predict prognosis and inform the treatment plans in the early stage. The necessary data for the response prediction are collected manually. The collected data are then processed through the feature selection segment. The Repeated Exploration and Exploitation-based Coati Optimization Algorithm (REE-COA) is employed to select the features. The selected weight features are input into the prediction process. Here, the prediction is performed by Multi-scale Dilated Ensemble Network (MDEN), where we integrated Long-Short term Memory (LSTM), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and One-dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1DCNN). The final prediction scores are averaged to develop an effective MDEN-based model to predict the patient’s response. The proposed MDEN-based patient’s response prediction scheme is 0.79%, 2.98%, 2.21% and 1.40% finer than RAN, RNN, LSTM and 1DCNN, respectively. Hence, the proposed system minimizes error rates and enhances accuracy using a weight optimization technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secondary malignancies, bone fractures, cognitive deficits, arterial fibrosis and cardiovascular disease are some of the effects of radiation. They are a broad category of unfavorable and frequently irreversible health effects that cancer patients face after radiation therapy1. These late effects are especially concerning for pediatric patients, and the likelihood of radiation late effects is greatly influenced by patient-intrinsic factors such as lifestyle, sex, age and genetics2. So, to enhance the diagnosis process for patients, it is crucial to determine the risks for patients because of the radiation late effects prior to radiotherapy3. Several methods have been developed for estimating the likelihood of radiation late effects, which typically involve irradiating patient-derived samples to monitor in vivo cellular effects and biomarkers during radiation exposure. Examples include assessing the apoptosis in normal blood cells, the frequency of chromosomal aberrations, and the dynamics of H2AX foci4. Moreover, potential putative markers show better results in terms of identifying risks for late effects of radiation that have been discovered by means of imaging studies and Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). Because of less predictive capacity, throughput, and cost-effectiveness, it remains challenging to accurately predict each patient’s response and their likelihood of experiencing adverse late health effects. Thus, new strategies are required for predicting the patient’s response effectively5. For retrieving useful information from medical images, DL mechanisms are more helpful than Machine Learning (ML) methods. Also, it is useful for real time implementations.

To minimize the size of tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is utilized. Adjuvant chemotherapy is used to improve the survival rate of breast cancer patients. Similarly, for controlling the growth of tumors and eliminating cancer cells, chemotherapy is utilized. Telomeres at chromosome termini serve as safeguards against genome deterioration and improper activation of DNA Damage Responses (DDRs)6. Because of cell division, oxidative stress, and aging, the telomeres become short. Environmental exposures and numerous lifestyle choices can cause telomere shortening7. Telomere length regulation and telomere length are strongly heritable traits that support independent variation in telomeric responsiveness to stresses. The lengthening and shortening of telomeres have been found by Ionizing Radiation (IR) exposure. Similarly, radio sensitivity could be used for identifying short telomeres8. A number of aging-related diseases, such as aplastic anemia, pulmonary fibrosis, and Cardio Vascular Disease (CVD), which are also the chronic diseases considered as radiation late effects. The above diseases are the effectors of short telomeres. Longer telomeres are associated with a higher risk of cancer, particularly leukemia, which may develop after IR exposure9. Therefore, patients with shorter telomeres are more likely to suffer from various diseases after radiation therapy, whereas those with longer telomeres are mostly affected by cancer.

Esophagitis, pneumonitis, fibrosis, and hematologic toxicities are some of the late side effects of concurrent chemoradiotherapy10. Some of these adverse effects have a major impact on survival as well as quality of life. Radiation biology has recently given a lot of attention to radiosensitivity prediction11. For radiation therapy, radiation sensitivity prediction is very valuable since it minimizes adverse effects and enhances the results12. Overall survival and local control (LC) techniques are used to assess the prognosis and effectiveness of radiation. Acute secondary cancer risk, treatment planning and radiation toxicity forecasts, following radiation therapy that is done by—models in current days13. A ML approach that uses an ensemble of gradient-boosted decision trees to learn complex relationships inside data is known as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). Numerous translational techniques are used in XGBoost, including the ability to treat radiation-induced fibrosis, forecast the likelihood of developing stomach cancer, and identify lung cancer14. The need for exceptionally huge volumes of data to build reliable, generalizable models is one of the drawbacks of ML. A cell-by-cell15 imaging-based method for telomere length assessment is Telomere Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (Telo-FISH), which can produce enough data to build ML models16. Telomere length measurements are required for the accurate prediction of a patient’s response using ML models17. Thus, a DL-based patient response prediction scheme is proposed.

The following points describe the supreme contribution of the established patient response prediction approach using DL:

-

To implement a DL-based patient response prediction framework to improve the treatment process by forecasting the patient’s response to specific therapies.

-

To improve the prediction performance, an optimization approach, REE-COA, is developed. It helps to increase the correlation coefficient and to minimize the variance of the same classes.

-

To acquire the weighted features, the weights are optimized by the proposed REE-COA and the features are selected based on the updated optimal solution.

-

To predict the patient’s response to the treatments, a DL approach named MDEN is suggested. It is the combination of RNN, LSTM and 1DCNN. It helps to see the benefits of the treatment given to patients.

-

To evaluate the efficiency of the recommended REE-COA model for predicting patient’s response, different DL techniques as well as heuristic approaches are used.

Organization of paper

The rest of the paper is organized as: Section “Literature survey” provides details about the existing patient’s response prediction strategies. Moreover, this segment explains the features and flaws of those methods. In “Structural illustration of proposed patient’s response prediction system using optimization-based ensemble learning”, the proposed concept, challenges in patient response prediction models and the structural illustration of investigated mechanism are given. The proposed optimization strategy for the optimization of features and weights are described along with the pseudocode and flowchart. Furthermore, the weighted feature selection process is also described in “Proposed optimization strategy-based optimal weighted feature selection for improving performance over prediction”. Section “Ensemble learning-based deep network for patient’s response prediction during radiotherapy” explains the developed DL strategy for patient’s response prediction. Each of the utilized DL techniques is explained individually. The empirical results of the investigated model are given in “Results and discussions”. Finally, “Conclusion and future works” concludes the paper with future scope.

Literature survey

Related works

In 2015, Hu et al.18 created a new technique for the detection of tumor patients. If a specific chemotherapy was useful for the patient or not was determined using molecular data collected from the patient’s tumor. The hormonal therapy choices could be influenced by the estrogen receptor status. Moreover, a predictor of response to cancer treatments could be developed using the gene expression data that reveal minute variations in tumors. The researchers aimed to predict who could respond favorably to sequential anthracycline-paclitaxel preoperative chemotherapy using gene expression data. They sought to identify a single gene signature that might be used to create predictors of pCR to neoadjuvant chemotherapy that potentially has practical uses, and they were considerably more accurate than DLDA-30. Furthermore, the developed mechanism could be useful for clinics. SLR and genetic algorithms were some of the multivariable techniques that could recognize a greater number of gene interactions.

In 2015, Bernchou et al.19 discovered that typical Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) images could be used to extract pre-treatment variables. Furthermore, they found that the response indicators could be used to anticipate how radiation will affect a patient’s lung density. In addition, they utilized CT scans to analyze the density changes caused by radiotherapy in lung cancer affected patients. They examined changes in lung density using CT scans taken during the treatment process to acquire early response signals. The capacity of CBCT indicators and pre-treatment variables to forecast lung density using radiotherapy was also analyzed.

In 2020, Defraene et al.20 offered a technique for forecasting the responses of lung cancer affected patients after chemo radiotherapy. The heart dose, dosimetric and clinical factors were considered for this research. fivefold cross-validation was done to estimate the performance of the prediction models. Moreover, 3 databases were utilized in this study. Finally, calibration and discrimination assessments were conducted to evaluate the performance of the investigated mechanism.

In 2021, Kim et al.21 developed an approach to identify individuals with Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy (SABR)treated lung cancer with clinical stage T1-2N0M0. Using time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, the model’s discriminating performance was validated. The developed approach obtained quantitative scores for the cumulative risk for 900 days. To explore the independent predictive significance of the model after changing the clinical parameters such as clinical T category, smoking status, sex and age, a multivariable Cox regression was used.

In 2022, Cozzarini et al.22 utilized a Pelvic Nodes Irradiation (PNI) to forecast the after-effects of SRT because of biochemical failures. For this purpose, a Poisson-based equation was used. They categorized the patients’ data into two groups. For analyzing various risks, unique fit methods were utilized. But the least square fit method was used for training the cohort data. Finally, calibration plots were used to evaluate the potential of the designed approach.

In 2023, Kim et al.23 utilized a Neural Network (NN) technique to predict the occurrence of RIL at the end of diagnosis process by combining Differential Dose Volume Histograms (dDVH) of heart and lungs, treatment-related factors, and patient characteristics. To train and validate their proposed model, 139 LA-NSCLC patients from different hospital’s multi-institutional data were gathered. The model was stabilized using a bootstrap approach and ensemble learning, and internal cross validation was done to assess the model’s performance. Using the Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves, the efficiency of their suggested model was compared to that of conventional models like Random Forests (RF) and Logistic Regression (LR).

In 2023, Chen et al.24 developed a polygenic risk scoring strategy for forecasting the uses of Radio Sensitivity (RS) in breast cancer affected patients. B0reast cancer affected patients were involved in this research. They identified the genes that were related to key prognostics with the help of LASSO regression. Using those genes, they developed a risk regression approach. Moreover, they detected the genes that were related to prognosis using Cox regression and differential expression analysis by conducting the Bayes differential technique. In adjuvant therapies, the drug sensitivity of Radio Resistance (RR) and (RS) were analyzed using the pRRophetic function.

In 2023, Wilkins et al.25 utilized immunohistochemical markers to assist the diagnosis process and enhance the prediction of patient’s responses. According to the prescribed fractionation plan, patients with clinical failure after Radiotherapy were matched without regularity. Diagnostic biopsy sections were evaluated with Immunohistochemical and scored a better PTEN, p-chk1, p53, HIF1, p16, Bcl-2, Geminin and Ki67. Each IHC biomarker’s prognostic value was assessed using multivariate and univariate conditional logistic regression models with matching age and strata.

In 2023, Pati et al.26 proposed CanDiag, an approach that utilized transfer DL for cancer diagnosis. CanDiag is an automated, real-time approach for diagnosing breast cancer using DL and mammography pictures from the Mammographic Image Analysis Society library. Additionally, feature reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) are also applied. The proposed approach achieved an accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score and Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 99.01%, 99%, 98.89%, 99.86%, 95.85%, 99.37% and 97.02%, outperforming some previous studies.

In 2024, Sahoo et al.27 utilized ML and Ensemble Learning (EL) techniques to enhance relapse and metastasis prediction. The developed framework is analyzed using The Cancer Gerome Atlas (TCGA) data and applied six basic ML models such as support vector machine, logistic regression, decision tree, random forest, adaptive boosting and extreme gradient boosting, then ensembled these models using weighted averaging, soft voting and hard voting techniques. The proposed approach achieved 88.46% accuracy, 9.74% precision, 94.59% sensitivity, 73.33% specificity, 92.11% F-score, 71.07% MCC and an AUC of 0.903. This provides better decision-making treatment.

Problem statement

Most conventional patient’s response prediction system increases the mortality rate. It is hard to predict the patient’s response because of the high similarity in patient responses. Traditional techniques for detecting patient responses have disadvantages such as time consuming and computational complexity. Therefore, many DL techniques have been developed for the patient’s response prediction system and advantages as well as disadvantages are listed in Table 1. XGBoost18 enhances the predictions for individual patient risk. Also, it effectively improves personalized treatment regimens and individual outcomes. But it provides instability outcomes, and it suffers from overfitting issues. SLR21 gives high accuracy, specificity and sensitivity values. Also, it effectively identifies the robust gene signatures of clinical relevance. Yet, it does not support early diagnosis treatment, and it does not identify the younger patient’s symptoms. RM19 effectively identifies patients with low risk of symptomatic toxic. Also, it reduces the multicollinearity in the genome to effectively identify the affected genome. Yet, it suffers from minimal radiation issues and it slightly decreases the survival rates. LR23 avoids the application of ineffective drugs and to improve the treatment efficacy. Also, it increases the risk prediction score. But it takes a lot of time to train the model, and it struggles to predict the time complexity. GSEA24 improves the prediction of prognosis and assists treatment stratification. Also, it effectively improves the treatment of cancer patients who have mild symptoms. Yet, it does not reinforce the concept for automatic prediction, and it increases the error rates. BCR25 effectively gives the warning of individual mortality risk. Also, it provides dose reductions to organs at risk. But it takes a lot of power to train the model, and the implementation cost is high. CNN22 increases the precision of delivery of the radiation dose. Also, it gives accurate prediction response for patients. But it struggles to train the model with large datasets, and it is hard to predict the matched patient’s response. ANN20 gives high dimensional dose distribution information in early stages. Also, it gives reliability and flexibility outcomes. Yet, it increases the throughput and predictive power, and it is unstable and more complicated. Hence, these drawbacks are the motivation for us to DL-based effective patient’s response prediction system.

Structural illustration of proposed patient’s response prediction system using optimization-based ensemble learning

Proposed patient’s response prediction scheme

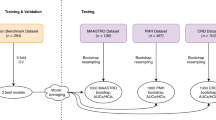

DL-based patient’s response prediction models require more amounts of data like the details about patient, their disease, treatment plans and the final outcomes. Gathering enough information is a challenge. As the collected data are said to be medical data, the quality of data should be high, otherwise the resultant outcomes will be inaccurate. To predict the response for chemotherapy of liver Metastases (mts), manual segmentation is done by the radiologists. It results in inter-reader variations in outputs and takes more time for segmenting. This method also causes more errors, so deep usage of DL approaches for forecasting the response of cancer patients is crucial. Most conventional models lack generalizability, so it is complicated to predict the response of patients from different regions and patients taking different kinds of therapies. Checking the volume of tumors is also a necessary factor while checking the side effects of radiotherapies. Furthermore, analyzing the benefits of medicine given to the patient during therapies could be useful for obtaining accurate response prediction results. The computational power and resource requirements of the conventional patient’s response prediction models are high. To solve these issues, a DL-based patient’s response prediction framework is recommended. The architectural view of the designed patient’s response prediction model is given in Fig. 1.

A DL-based patient’s response prediction system is developed to effectively predict the responses of cancer affected patients for various therapies. The required data to implement this model is gathered manually. An REE-COA is proposed to optimize features and weights to minimize variance and maximize the correlation coefficient of data of the same class. The optimized features and weights are multiplied to generate the weighted features. Those weighted features are passed to the prediction stage. For performing the prediction, an MDEN approach is proposed. MDEN is created by combining the DL techniques named LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN. The weighted features are given separately to these mechanisms. Prediction scores from these three models are averaged to obtain a final prediction result. Various optimization approaches and DL models are considered to check the performance of the investigated patient’s response prediction model using DL.

Dataset collection

In this research, the data collection process is done manually. The dataset comprises 10,000 instances and includes 16 key columns related to patient health and treatment outcomes. The attributes in the dataset are illustrated in Table 2. The dataset was split into 3 subsets which are the training set, validation set and testing set. The training set contains 70% (7,000) instances. Similarly, the validation set contains 20% and the testing set contains 10%. This split ensures a balanced utilization of data for model development, evaluation and testing, providing an accurate and reliable predictive system.

Proposed optimization strategy-based optimal weighted feature selection for improving performance over prediction

Traditional COA

COA28 is a meta-heuristic algorithm developed based on the escaping and hunting behaviors of the coati. They belong to the family Procyonidae. The size of the female coati is so small when compared to male coati. Male coatis have large and sharp teeth. Bird eggs, crocodile eggs, rodents, lizards, small vertebrate prey are some of the foods eaten by coatis. But green iguana is their favorite food. It is occasionally seen in trees. A group of coatis join and hunt these iguanas. To hunt iguanas, one or two coatis climb trees to scare them. If the iguana is scared, it falls from the tree. At that time, the other coatis attacked the iguana.

The positions of coatis are allocated in a random manner. The members of this COA approach are coatis. The decision variables are estimated by the coati’s position. The initialization of COA is given in Eq. (1).

Here, the expression \(a\) defines the random number. The upper and lower limits are specified as \(pb_{l}\) and \(eb_{l}\), concurrently. Total count of coatis is represented as \(C\). The total number of decision variables is indicated as \(r\). The \(l^{th}\) decision variable’s value is denoted as \(t_{k,l}\). The population matrix in Eq. (2) displays the allotment of coatis in the search space.

Various objective functions are obtained because of assigning candidate solutions. For \(k^{th}\) coati, the objective function is indicated as \(N_{k}\) and its vector value is mentioned as \(N\). The escaping and hunting are the two phases present in the COA.

Hunting phase: The coatis form a group and attack the prey by climbing the tree. So, the positions of the coatis are changed in the search area. The position of iguana is also the position of best coati. The positions of coatis, which are on the trees, are evaluated using Eq. (3).

In the above expression, the new position of coati is termed as \(t_{k,l}^{ps1}\). The terms \(G_{l}\) and \(v\) refers the iguana and an integer value, simultaneously. The iguana’s position changes when it falls from the tree, and the positions of the coatis change when they come to the ground. This process is expressed in Eqs. (4) and (5).

In Eq. (5), the iguana’s position on the ground is indicated as \(G_{l}^{S}\). If the new position of coati provides a better objective value, then the position of coati is updated based on Eq. (6).

In the above equation, the term \(T_{k}^{pos1}\) specifies the new position of coati. The objective function value is symbolized as \(N_{k}^{pos1}\). The greatest integer function is given as \(\left\lfloor . \right\rfloor\).

Escaping phase: This phase mathematically models the coatis’ ability to escape from attackers. They try to find a safe place to hide from the predator. The numerical expression of the escaping phase is provided in Eqs. (7) and (8).

Here, the local upper limit and the local lower limit is referred as \(pb_{l}^{LO}\) and \(eb_{l}^{LO}\), correspondingly. The number of iterations is characterized as \(f\). The new position of coati is given in the below Eq. (9).

In Eq. (9), the coati’s new position in the exploitation phase is mentioned as \(T_{k}^{pos2}\). The pseudocode of the traditional COA is given in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 COA

Implemented REE-COA

A REE-COA is developed by improving the conventional COA to progress the effectiveness of the investigated patient’s response prediction model. Furthermore, it is optimizing features and weights to maximize the correlation coefficient and reduce the variance of data of the same class. COA can solve optimization problems without control parameters, however it has a lower convergence rate. So, the new algorithm REE-COA is proposed by enhancing the exploration and exploitation phase of COA. At first, the exploration and exploitation phases of COA are executed; then again, these stages are performed for improving the performance of the optimization approach. With the help of optimization using the developed REE-COA, the prediction performance is highly improved. Thus, the capability of the global search phase is improved in the REE-COA. The pseudocode and the flowchart of the implemented REE-COA are displayed in Algorithm 2 and Fig. 2.

The primary objective of selecting REE-COA optimization algorithm was for chosen feature extraction due to its enhanced performance compared to traditional methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Genetic Algorithms (GA). Unlike PCA, which assumes linear relationships and does not consider class labels. Additionally, PCA can lead to a loss of interpretability, where as REE-COA selects a minimal, interpretable set of features, making it more suitable for medical applications. Similarly, GA can be computationally expensive, while REE-COA offers faster convergence and better balance of exploration and exploitation. This ability of the REE-COA allows to find an accurate and optimal feature subset. Hence, the combination of its efficiency, interpretability and ability to select relevant features based on class labels makes REE-COA the optimal choice for the feature selection task in this study.

Algorithm 2 REE-COA

Optimal weighted feature selection

The optimal solution obtained using the proposed REE-COA selects the necessary features. Then the weights are optimized using the recommended REE-COA. The selected features are multiplied with the optimized weights to acquire the weighted features. The optimized weights and features are indicated as \(T_{R}^{WE}\) and \(A_{R}^{FE}\), correspondingly. Weighted features are obtained via Eq. (10).

In the above equation, the obtained weighted feature is represented as \(CO_{R}^{WF}\). By selecting the features using the updated solution, the unwanted features as well as the noise are removed from the input data. Thus, the weighted feature selection process improves the prediction phase by reducing overfitting. The objective of the weighted feature selection is to improve the correlation coefficient and decrease the variance of data of the same class by optimizing the weights and features. Below Eq. (11), provides the objective of the weighted feature selection.

Here, the variance is denoted as \(D\). The correlation coefficient is specified by the term \(SL\). The term \(TH\) expresses the objective function. The features \(A_{R}^{FE}\) are selected in the range of \(\left[ {1,56} \right]\). The optimized weight lies in the interval of \(\left[ {0.01,0.09} \right]\). The following Eqs. (12) and (13) present the calculations of correlation coefficient and variance.

Here, the variable samples are mentioned as \(k\) and \(l\). The mean value is referred as \(\overline{k}\) and \(\overline{l}\). The total count of data points is represented as \(d\).

The mutual information scores for selected features are provided in Table 3. These indicate the strength of the relationship between each feature and the target variable. Higher values suggest a stronger correlation with the target, showing their significance in the prediction. The features are selected on the basis of mutual information scores and threshold which helps to filter out irrelevant or weak features and ensure that model is trained with most informative attributes, leading to improved model performance.

Ensemble learning-based deep network for patient’s response prediction during radiotherapy

Basic LSTM

The LSTM network predicts cancer patients to the therapies. The input-weighted features \(CO_{R}^{WF}\) are given to the LSTM. LSTM29 can control long term dependencies. It consists of four neural networks, and the structure of LSTM is a little complicated. The output, input and forget gates carefully regulate the LSTM to add data in the cell state. The unnecessary data from the previous step is eliminated by the forget gate. This step is expressed in Eq. (14).

Here, the input is symbolized as \(b_{k}\), and the forget gate is specified as \(A_{k}\). The output at time \(k\) is indicated as \(g_{k - 1}\). The bias and weight matrix are characterized as \(l_{a}\) and \(Y_{a}\), simultaneously. The new data are added to the cell state by the input gate. In the input gate, a tanh layer and a sigmoid layer are presented. The role of the input gate is given in Eq. (15).

Here, the input gate is symbolized as \(R_{k}\). For the new candidates, a new vector value is generated by the \(\tanh\) layer, is shown in Eq. (16).

In Eq. (16), the vector value is represented as \(\tilde{V}_{k}\). The process of cell state is computed using Eq. (17).

From the cell state, the correct output is decided by the output gate, and it is mathematically expressed in below Eq. (18).

In the above expression, the output gate is specified as \(E_{k}\). The output value is determined using Eq. (19).

Here, the output obtained from cell state is mentioned as \(g_{k}\). The predicted score from LSTM is termed as \(R_{M}^{LS}\). The pictorial view of LSTM is shown in Fig. 3.

Basic RNN

The RNN mechanism predicts patient’s responses to treatments. The RNN30 approach receives the input weighted features \(CO_{R}^{WF}\) for obtaining prediction results. The RNN can forecast the symbol of next sequence by learning the probability distribution. The function of RNN is expressed in the following Eq. (20).

Here, the term \(p\) specifies the time; the non-linear activation function is expressed by the term \(A\). The term \(u\) represents the hidden state. The variable length sequence is estimated using Eq. (21).

The output at a time \(p\) is computed by the below Eq. (22).

Here, the weight matrix is denoted as \(R\). The value of S is estimated using EQ. (23).

Therefore, new samples are created using this learned distribution. The final prediction scores obtained using RNN is indicated as \(P_{Y}^{RN}\). Figure 4 visualizes the structure of RNN.

Basic 1DCNN

The weighted features \(CO_{R}^{WF}\) are given to 1DCNN31 for obtaining another prediction score. The activation functions, dropout layers, pooling layers, convolution layers and 1-dimensional convolution layers are presented in the 1d-CNN. The 1D data are handled by these layers. The subsampling elements filter size, neurons of each layer and the CNN layers are some of the hyper-parameters used for configuring the 1DCNN. The input to the 1DCNN is processed by the convolutional layers. The inputs are multiplied with weights by the convolution operation. Then the feature maps are created using filtering operations. Specific values are generated at the end of the convolution operation to form the feature maps.

ReLU activation is used to obtain the values of feature maps after the computation. If the resultant value is a negative integer, then the ReLU function provides output as zero. If it’s a positive integer, the ReLU function does not make any changes to the output. The process of the RELU function is given in Eq. (24).

In the above equation, the positive output is termed as \(L(i)\) and the input is mentioned as \(i\). Then, the feature maps are positioned by the subsampling technique in the pooling layer. It is used to eliminate overfitting problems. Mapped pooled features are obtained after the pooling process in 1DCNN. Based on the type of pooling, the mapped pooled features are selected. If the applied pooling type is average pooling, the values of the feature set are averaged. But, in maximum pooling, a maximum value is assigned to the features. Dropout layers are utilized in 1DCNN to maximize the overall performance of the network. The processed active inputs are estimated via Eq. (25).

To avoid the network burden, the dropout rate is chosen by the scaling process. Finally, the results are mapped by the activation function, fully connected layer and dense layers. The final prediction result from 1DCNN is termed as \(S_{Z}^{DC}\). The diagrammatic representation of the 1DCNN is displayed in Fig. 5.

Implemented MDEN for patient response prediction

An MDEN prediction model is developed to predict the response of the patients who are taking treatments for cancer. For curing the cancer disease, the chemotherapy is given to the patients. But if the patient is really getting benefited by this treatment should be ensured. So, predicting the response of the patient’s helps to plan the further diagnosis process. This structure is formed by combining the LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN architectures. The weighted features are given as input to the DL models for obtaining separate prediction scores. The prediction scores from LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN are averaged to attain the final prediction results.

For increasing the prediction performance, enlarging the receptive field, the multi-scale approach is utilized. More number of kernel filters is used in the multi-scale mechanisms. The dilation process is expressed in Eq. (26).

Here, the dilation rate is specified as \(l\). The width and length of the filter is represented as \(B\) and \(A\), simultaneously. The input and output of the dilation is mentioned as \(y\left( {a,b} \right)\) and \(d\left( {a,b} \right)\), concurrently. The receptive fields are expanded by large filters. By using the MDEN, performance degradation, more amounts of trainable parameter and the gradient vanishing problems are solved. Moreover, it helps to learn the data faster and the performance of the response prediction is increased by the integration of DL approaches. The schematic view of the suggested MDEN-based patient’s response prediction model is shown in Fig. 6.

The combination of LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN within the MDEN was chosen to utilize the unique strengths of each component to improve the overall predictive performance for patient response prediction. LSTM is included for its ability to capture long-term dependencies and temporal relationships within sequential data, which is essential for medical predictions where historical patient data, such as previous treatments or clinical history, plays a significant role in predicting future outcomes. RNN, on the other hand is valuable for processing sequential data and capturing short-term dependencies. While RNNs are more expected to cause vanishing gradient issue than LSTM, they still provide important insights into more intermediate, short-term or patterns in patient data, such as fluctuation in biomarkers or recent clinical events. 1DCNN is employed to capture local patterns and hierarchical features within sequential data. Convolutional layers are effective in extracting spatial relationships from data, even when the input is essential, such as time-series or temporal data. The model can identify essential features such as abrupt changes or local trends, which are crucial for accurate response prediction. These components are combined into an ensemble network with multi-scale dilated convolutions, they collectively benefit from their individual strengths. LSTM’s ability to capture long-term dependencies, RNN’s focus on short-term patterns and 1DCNN’s ability to learn spatial hierarchies in sequential data. This approach ensures that the model can extract both global and local features, providing a more comprehensive and representation of the patient’s data, which significantly enhances prediction accuracy.

The MDEN with its multi-scale architecture comprising LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN, offers significant predictive power by capturing long-term dependencies, short-term patterns and hierarchical features. The feasibility of implementing MEDN depends on factors like dataset size, available hardware and optimization techniques for real-time or near real-time clinical applications. However, larger medical datasets require higher processing time and more memory usage. Despite the computational demand of the MDEN model, its enhanced performance is outperformed over existing solutions is demonstrated through its evaluation metrics. While computational resources are a consideration, the model’s reliability in delivering accurate predictions justify this trade-off, particularly in critical scenarios where misdiagnoses could lead to several consequences.

Results and discussions

Experimental setup

The proposed patient’s response prediction model using DL was implemented via Python. For examining the efficiency of the suggested patient’s response prediction mechanism, various DL techniques and heuristic approaches were considered. To implement this method, the total population, iterations and chromosome length utilized was 10, 50 and 200, concurrently. The Tomtit Flock Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm (TFMOA)32, Eurasian Oystercatcher Optimizer (EOO), Dingo Optimizer (DO)33 and COA28 were the heuristic approaches used for the validation purpose. Likewise, the DL techniques, including Residual Attention Network (RAN)34, LSTM29, RNN30 and 1DCNN31 were also used for the validation process of investigated patient’s response prediction model.

Computations of negative measures

Some of the negative measures are considered for this research to evaluate the prediction performance of the investigated approach.

The “Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error” (SMAPE) is used for estimating the error percentage between the forecasted and actual value. It is computed using Eq. (27).

The variations between calculated and actual values are estimated by the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measure, and it is calculated via Eq. (28)

The prediction accuracy is verified by the Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE) measure. The formula for MASE is given in Eq. (29).

The one-norm measure is used to evaluate the sum of the absolute actual values. It is estimated to be using Eq. (30).

The standard deviation between data points and the regression line is estimated using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). The computation for RMSE is provided below Eq. (31).

The square of the vector elements is evaluated using the measure named two-norm. The two-norm is evaluated via Eq. (32).

The variances between data are calculated using the Mean Percentage Error (MEP) and it is estimated by Eq. (33).

In the above expressions, the predicted value is mentioned as \(P_{j}\). The total count of observations is indicated as \(b\). The term \(U\left( j \right)\) specifies the actual value.

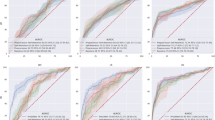

Prediction performance evaluation

The patient’s response prediction approach using the developed REE-COA-MDEN is verified with other DL techniques to make sure the effectiveness of the forecasting performance. The pictorial representation of the result comparison among various DL mechanisms is shown in Fig. 7 and the tabular representation is shown in Table 4. The RMSE of the developed REE-COA-MDEN is 8.10%, 7.60%, 5.55% and 5.02% enhanced than RAN, LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN at a learning percentage of 55. Therefore, the prediction performance of the presented REE-COA-MDEN is greater than other DL approaches.

Table 4 presents the SMAPE values for all the models which are RAN, LSTM, RNN, 1DCNN and MDEN across six learning rates ranging from 35 to 85%. SMAPE measures the prediction error with the lower values indicating better performance. Among the models, MDEN and 1DCNN consistently indicate lower SMAPE values, highlighting their performance across varying learning rates. In comparison, RAN and LSTM shows relatively higher error values, especially at 75% and 85%.

Convergence determination

The convergence of the proposed REE-COA-MDEN-based response prediction of cancer patient’s model is evaluated among different heuristic approaches to validate the ability of the investigated algorithm. Figure 8 provides the cost function assessment of the offered REE-COA-MDEN. At an iteration of 30, the convergence of the REE-COA-MDEN is 14.28%, 16.27%, 21.73% and 20% superior to DO-MDEN, EOO-MDEN, TFMOA-MDEN and COA-MDEN. Thus, the resultant outcomes showed that the cost requirements of the recommended REE-COA-MDEN-based patient’s response prediction framework are not higher like other algorithms.

Performance comparison before and after feature selection

Statistical tests for validating the impact of the feature selection process are conducted and the results are provided in Table 5. The RMSE value of the proposed method after feature selection is improved by 3.46%, SMAPE by 8.01%, MAE by 4.50%, MASE by 2.56%, ONE-NORM by 3.64% and TWO-NORM by 1.51%, when compared to the values before feature selection. These results confirm that the feature selection process significantly improves the model’s predictive performance, ensuring low error rates.

Statistical report over various conventional algorithms

Statistical tests for ensuring the efficacy of the suggested algorithm are conducted, and the results are provided in the below Table 6. The MEAN value of the proposed REE-COA-MDEN-based patient’s response prediction technique is better than DO-MDEN, EOO-MDEN, TFMOA-MDEN and COA-MDEN with 19.58%, 16.63%, 18.23% and 9.58%, simultaneously. Thus, the performance of the offered algorithm is progressed than many other optimization approaches.

Performance validation of developed MDEN

The overall performance in predicting the response of patients using DL is evaluated by contrasting the results with various deep learning techniques. The simulation outcomes of the proposed mechanism are given in Table 7. The MASE of the developed MDEN-based patient’s response prediction scheme is 0.79%, 2.98%, 2.21% and 1.40% finer than RAN, RNN, LSTM and 1DCNN, respectively. Hence, the investigated MDEN-based patient’s response prediction approach minimized the error rates and obtained accurate outcomes.

Performance evaluation over algorithms based on feature selection

The features and weights from the data are selected with the help of the proposed REE-COA-MDEN to get the optimal weighted features. These features are given to the prediction process for forecasting the patient’s response. Therefore, the performance of the prediction process is compared among traditional optimization strategies that are depicted in Table 8. The selected features are multiplied with optimized weights to attain the weighted features. Therefore, the prediction performance is enhanced by the weighted features that are shown clearly in Table 6. The SMAPE of the presented REE-COA-MDEN is 6.50%, 4.73%, 3.59% and 2.88% better than DO-MDEN, EOO-MDEN, TFMOA-MDEN and COA-MDEN. Hence, the results proved that the patient’s response prediction performance is enhanced by the weighted feature selection process using the proposed REE-COA-MDEN.

Conclusion and future works

A patient response prediction technique using DL was executed to effectively predict the responses of cancer affected patients for their therapies. Essential data for this research was gathered manually. An REE-COA was proposed to optimize the features and weights for reducing the variance and increasing the correlation coefficient of data of the same class. The optimized features and weights were multiplied to generate the weighted features for further prediction process. For performing the prediction, an MDEN approach was proposed. MDEN was developed by integrating the DL techniques named LSTM, RNN and 1DCNN. The weighted features were given separately to these techniques for obtaining prediction scores. Prediction scores from these three models were averaged to obtain a final prediction result. The empirical results were examined with various optimization approaches and DL models to verify the performance of the investigated patient’s response prediction model using DL. In Fig. 7 the SMAPE of the designed REE-COA-MDEN-based patient’s response prediction scheme was 8%, 5.84%, 4.16% and 2.42% more desirable than RAN, RNN, LSTM and 1DCNN at a learning percentage of 75. Therefore, the suggested patient’s response prediction framework, with the help of DL algorithms, obtained more precise results. Soon, we plan to extend the work and experimentation with more algorithms.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural networks

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- REE-COA:

-

Repeated exploration and exploitation-based coati optimization algorithm

- RCOA:

-

Coati optimization algorithm

- MDEN:

-

Multi-scale dilated ensemble network

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- RNN:

-

Recurrent neural network

- 1DCNN:

-

One-dimensional convolutional neural network

- GWAS:

-

Denome-wide association studies

- DDRs:

-

Dna damage responses

- CVD:

-

Cardio vascular disease

- IR:

-

Ionizing radiation

- LC:

-

Local control

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

- Tele-FISH:

-

Telemere fluorescence in situ hybridization

- SABR:

-

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CBCT:

-

Cone-beam computed tomography

- NN:

-

Neural network

- DDVH:

-

Differential dose volume histograms

- RF:

-

Random forest

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- ROC:

-

Receiver operatying characteristics

- RS:

-

Radio sensitivity

- RR:

-

Radio resistance

- PNI:

-

Pelvic nodes irradiation

- TFMOA:

-

Tommit flock metaheuristic optimization algorithm

- EOO:

-

Eurasian oystercatcher optimizer

- DO:

-

Dingo optimizer

- RAN:

-

Residual attention network

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- MCC:

-

Matthew’s correlation coefficient

References

Shao, Y. Prediction of three-dimensional radiotherapy optimal dose distributions for lung cancer patients with asymmetric network. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 25(4), 1120–1127 (2021).

Belfatto, A. Adaptive mathematical model of tumor response to radiotherapy based on CBCT data. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 20(3), 802–809 (2016).

Renzhi, Lu. Learning the relationship between patient geometry and beam intensity in breast intensity-modulated radiotherapy. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53(5), 908–920 (2006).

Maemoto, H. et al. Predictive factors of uterine movement during definitive radiotherapy for cervical cancer. J. Radiat. Res. 58(3), 397–404 (2017).

Jalalifar, S. A., Soliman, H., Sahgal, A. & Sadeghi-Naini, A. A self-attention-guided 3d deep residual network with big transfer to predict local failure in brain metastasis after radiotherapy using multi-channel MRI. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 11, 13–22 (2023).

Jia, Q. et al. OAR dose distribution prediction and gEUD based automatic treatment planning optimization for intensity modulated radiotherapy. IEEE Access 7, 141426–141437 (2019).

Elhaminia, B. Toxicity prediction in pelvic radiotherapy using multiple instance learning and cascaded attention layers. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27(4), 1958–1966 (2023).

Sosa-Marrero, C. Towards a reduced in silico model predicting biochemical recurrence after radiotherapy in prostate cancer. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68(9), 2718–2729 (2021).

Wang, C.-Y., Lee, T.-F., Fang, C.-H. & Chou, J.-H. Fuzzy logic-based prognostic score for outcome prediction in esophageal cancer. IEEE Trans. Inf Technol. Biomed. 16(6), 1224–1230 (2012).

Kai, Y. Semi-automated prediction approach of target shifts using machine learning with anatomical features between planning and pretreatment CT images in prostate radiotherapy. J. Radiat. Res. 61(1), 285–297 (2019).

Luo, Y. Development of a fully cross-validated bayesian network approach for local control prediction in lung cancer. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 3(2), 232–241 (2019).

Cui, S., Luo, Y., Tseng, H.-H., Haken, R. K. T. & El Naqa, I. Artificial neural network with composite architectures for prediction of local control in radiotherapy. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 3(2), 242–249 (2019).

Pham, T. D., Ravi, V., Fan, C., Luo, B. & Sun, X.-F. Classification of IHC images of NATs with ResNet-FRP-LSTM for predicting survival rates of rectal cancer patients. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 11, 87–95 (2023).

McIntosh, C. & Purdie, T. G. Contextual atlas regression forests: multiple-atlas-based automated dose prediction in radiation therapy. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35(4), 1000–1012 (2016).

Wang, R., Liang, X., Zhu, X. & Xie, Y. A feasibility of respiration prediction based on deep Bi-LSTM for real-time tumor tracking. IEEE Access 6, 51262–51268 (2018).

Park, S., Lee, S. J., Weiss, E. & Motai, Y. Intra- and inter-fractional variation prediction of lung tumors using fuzzy deep learning. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 4, 1–12 (2016).

Liao, W. & Pu, Y. Dose-conditioned synthesis of radiotherapy dose with auxiliary classifier generative adversarial network. IEEE Access 9, 87972–87981 (2021).

Hu, W. High accuracy gene signature for chemosensitivity prediction in breast cancer. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 20(5), 530–536 (2015).

Bernchou, U., Hansen, O. & Schytte, T. Prediction of lung density changes after radiotherapy by cone beam computed tomography response markers and pre-treatment factors for non-small cell lung cancer patients. Radiother. Oncol. 117(1), 17–22 (2015).

Defraene, G., Dankers, F. J. W. M. & Price, G. Multifactorial risk factors for mortality after chemotherapy and radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 152, 117–125 (2020).

Kim, H., Lee, J. H. & Kim, H. J. Extended application of a CT-based artificial intelligence prognostication model in patients with primary lung cancer undergoing stereotactic ablative radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 165, 166–173 (2021).

Cozzarini, C. & Olivieri, M. Accurate prediction of long-term risk of biochemical failure after salvage radiotherapy including the impact of pelvic node irradiation. Radiother. Oncol. 175, 1 (2022).

Kim, Y., Chamseddine, I. & Cho, Y. Neural network based ensemble model to predict radiation induced lymphopenia after concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer from two institutions. Neoplasia 39, 100889 (2023).

Chen, H., Huang, Li., Wan, X. & Ren, S. Polygenic risk score for prediction of radiotherapy efficacy and radiosensitivity in patients with non-metastatic breast cancer. Radiat. Med. Protect. 4(1), 33–42 (2023).

Wilkins, A., Gusterson, B., & Tovey, H. Multi-candidate immunohistochemical markers to assess radiation response and prognosis in prostate cancer: Results from the CHHiP trial of radiotherapy fractionation. eBioMedicine 88 (2023).

Sahoo, G. et al. Predicting breast cancer relapse from histopathological images with ensemble machine learning models. Curr. Oncol. 31(11), 6577–6597 (2024).

Pati, A., Parhi, M., Pattanayak, B. K., Sahu, B. & Khasim, S. CanDiag: Fog empowered transfer deep learning based approach for cancer diagnosis. Designs 7(3), 57 (2023).

Dehghani, M., & Montazeri, Z. Coati optimization algorithm: A new bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl. Based Syst. 259, 110011 (2023).

Huang, R., Wei, C., Wang, B., Yang, J., Xu, X., Wu, S., & Huang, S. Well performance prediction based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 208 (2022).

Cho, K., Merrienboer, B. V., Gulcehre, C., Bahdanau, D., Bougares, F., Schwenk, H., & Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. Comput. Lang. (2014).

Qazi, E. U. H., Almorjan, A., & Zia, T. A one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) based deep learning system for network intrusion detection. Appl. Sci. 12 (2022).

Panteleev, A. V., & Kolessa, A. A. Application of the tomtit flock metaheuristic optimization algorithm to the optimal discrete time deterministic dynamical control problem. vol.15 (2022).

Bairwa, A. K., Joshi, S., & Singh, D. Dingo Optimizer: A nature-inspired metaheuristic approach for engineering problems. Math. Probl. Eng. (2021).

Ganesan, S., Ravi, V., Krichen, M., & Alroobaea, S. V. R. Robust malware detection using residual attention network. In IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), pp. 1–6 (2021).

Salim, A. & Jummar, W. K. Farah Maath Jasim and Mohammed Yousif, "Eurasian oystercatcher optimiser: New meta-heuristic algorithm. J. Intell. Syst. 31(1), 1 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manogaran, N., Panabakam, N., Selvaraj, D. et al. An efficient patient’s response predicting system using multi-scale dilated ensemble network framework with optimization strategy. Sci Rep 15, 15713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00401-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00401-y