Abstract

In this paper, we investigate the newly formulated (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation, highlighting its utility in describing the dynamics of nonlinear waves. This novel equation effectively incorporates increased dispersion and nonlinear effects, thereby enhancing its applicability across various physical scenarios. This model especially useful when modeling nonlinear phenomena in materials that simpler linear models would not accurately describe. Also serve as a founding model for numerical simulations in computational fluid dynamics and solid mechanics. We deploy both the Sardar Sub-Equation Method (SSEM) and the Simple Equation Method (SEM) to derive a broad spectrum of unique traveling wave solutions. These solutions have been thoroughly verified with Mathematica and include a wide variety of mathematical functions such as trigonometric hyperbolic and exponential forms. To provide a comprehensive visual representation of these solutions, we generate 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs by meticulously setting the relevant parameters in Wolfram Mathematica. The solutions obtained illustrate various phenomena, such as dark, bright, kink, singular, periodic, periodic singular, and compacton solitons. The innovation of this work is in the systematic investigation and description of several types of soliton solution over a wide variety of nonlinear equations. Not only does this thorough study advance theoretical insight but also increase practical applications in areas like optical fiber communication and engineering. Additionally, we investigate the modulation instability (MI) of the proposed model, further elucidating its significance in the context of nonlinear wave propagation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs) are essential tools for explaining a broad range of intricate phenomena in the fields of engineering, physics, and biology1,2. Their importance rests in their ability to capture complex behaviors that linear equations are frequently unable to adequately model. A vital class of NLPDEs are nonlinear evolution equations (NLEEs). Research on NLEEs has become popular and important because of the extensive applications of NLEEs in the fields of engineering, physics, and mathematical sciences. Nonlinear sciences, including optical engineering, condensed matter physics, fluid dynamics, electromagnetic theory, particle diffusion, nuclear physics, plasma physics, and many more, can benefit from the application of mathematical models based on NLEEs3,4. To enhance our understanding of nonlinear phenomena and their practical applications, it is imperative to precisely solve the relevant NLEEs. Some essential components of all NLEEs are lump waves, multi-soliton, rogue waves, breathers, and their dynamical features5,6,7. It is worthwhile to carry out additional research on these equations or their different kinds because of their potential applications in water, Bose-Einstein condensates, the ocean, nonlinear optics, and other fields.

In the field of nonlinear science, NLPDEs have gained popularity and have been utilized to characterize issues in numerous domains. NLPDEs find applications in the fields of medical imaging, population modeling, electrical nerve communication, and the appropriate delivery of oxygen to healing tissues8,9,10. NLPDEs are widely used in various physical applications. They play a crucial role in areas such as wave propagation and scattering, magnetic resonance imaging, modeling traffic congestion, fluid dynamics, and the study of ultrasonic and turbulent flows. Additionally, they are important in understanding magnetohydrodynamic movements in pipelines and acoustic transmission. Their adaptability and capacity to model intricate behaviors make them essential resources in both theoretical and practical physics11. A variety of techniques have been developed to obtain precise solutions for NLPDEs. These include the extended and modified tanh-function method12, the Hirota bilinear method13, the modified Sardar sub-equation method14, Hirota’s direct method15, the newly enhanced modified generalized sub-ODE method16, the Lie symmetry method17, the He-Laplace variational iteration method18, the homotopy perturbation method19, the exp\((-\Phi (\eta ))\)-expansion method20,21,22,23, the Jacobi elliptic function expansion method24, the tanh method25, the extended tanh method26, the modified generalized exponential rational function method27, the sine-Gordon expansion method28, the modified simple equation method29, the modified extended tanh method30, the improved F-expansion method31, the extended hyperbolic functions technique32,33, the unified tanh approach34, the new Kudryashov method35, the modified extended auxiliary equation mapping approach36,37, the new auxiliary equation technique38,39, the modified Khater (MK) method40, the \((\frac{w}{g})\)-expansion approach,41, the extended hyperbolic function technique42, the variational iteration method43, the Backlund transform method44, the extended auxiliary mapping method45 among others. These diverse approaches offer specialized methods for analyzing the complex structure of nonlinear equations, greatly enhancing our understanding of intricate wave interactions in various scientific fields.

Optical solitons are a type of electromagnetic wave that maintain a stable propagation pattern in nonlinear media. This stability arises from a strong balance between the linear effects of diffraction or dispersion and the nonlinear effects of the medium. In the realm of optical fiber communications, solitons are particularly significant as they enhance the efficiency and capacity of communication networks. They achieve this by maintaining their shape and speed over long distances, which is essential for effective data transmission46,47. Furthermore, one can conceptualize the genetic system of living organisms as a tripartite unity that encompasses both structural and functional components. This system includes holographic structures that are capable of transmitting information via solitons, which can operate similarly to magnetic and sound waves. In acupuncture, solitons manifest as high-amplitude, nonlinear solitary pulses that efficiently compress and direct the body’s energy48. Their mechanism resembles shock waves, particularly due to their hydrophilic jumps, which enable them to influence the environments of nearby smaller waves. As solitons propagate, they draw in these smaller waves, assimilating them into their larger potential waves, thereby allowing them to harness and utilize this energy. This complex interaction highlights the multifaceted role of solitons in both communication technologies and biological systems49. The investigation of NLEEs is important because it gives information on a broad array of physical phenomena, ranging from fluid dynamics to optical communications. This paper points out different types of exact solutions, such as solitary and periodic waves, that are important in the understanding of these systems. We present strong methods such as the Sardar sub equation method and the simple equation method, which are renowned for their effectiveness in revealing exact solutions. By placing our research within the framework of previous literature, we highlight its novelty and importance. Sakovich equation is a NLPDE formulated by Sakovich in 1996. It is characterized by having Korteweg-de Vries (KdV)-type solitons and has been a focus of major research work due to its utility in many applications. This equation is Painlevé integrable, i.e., it can satisfy the Painlevé test, which is a test for whether a nonlinear partial differential equation is integrable. This equation is applied to the study of solitary waves, specifically in nonlinear dispersive systems. Some examples include the examination of rogue waves in oceanography, in which it is utilized to model sudden large waves. This model find applications in wide areas of physics, mathematics, and other sciences, especially in the theory of waves, soliton theory, plasma physics, biology and chemistry, and nonlinear phenomena. In various disciplines, the (2 + 1)-dimensional second-order Sakovich equation is an essential mathematical model that helps to investigate the behavior of water waves within a long, narrow, hollow tube. A notable study conducted by Wazwaz et al. in 2020 introduced two innovative Painlevé-integrable extended Sakovich equations across both (2 + 1) and (3 + 1) dimensions. This research effectively derived a variety of soliton solutions, as well as multiple complex soliton solutions corresponding to these models50. Subsequently, in 2022, Sachin Kumar et al. expanded on this work by examining different analytical wave solutions and analyzing the dynamic behaviors of the newly formulated (2 + 1)-dimensional Sakovich equation. In a 2025, Aly R. Seadway et al. focused on solitary wave solutions of the extended Sakovich equation, obtained various types of analytical solutions, including trigonometric, hyperbolic, exponential, and rational function forms. They established several standard forms of novel and unique closed-form solutions through the application of two relatively recent techniques: the extended Jacobian elliptic function expansion method and Lie symmetry analysis. In this context, Lie vectors were employed to construct an optimal arrangement of the one-dimensional subalgebras, thereby enhancing the understanding of the solutions in relation to the underlying symmetries of the equations51. The major purpose of employing the Sakovich equation is to gain a better insight into nonlinear dynamics through investigation of the complicated behavior of nonlinear systems, especially wave propagation phenomena. This is about creating sound mathematical models that accurately describe a variety of physical systems like fluid mechanics and applications in optical fibers.

Both the Sardar Sub-Equation Method (SSEM) and the Simple Equation Method (SEM) are recognized as effective approaches for deriving solutions to nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs). One of the key advantages of these two methods over existing techniques is their ability to generate a wider array of exact soliton solutions, including novel solutions with additional parameters, in a straightforward and intuitive manner. In 2022, Melih Cinar et al. employed the SSEM to extract a variety of optical solitons from the dimensionless Fokas-Lenells equation, which included a perturbation term52. This research led to the identification of several types of solitons, such as periodic solitons, dark solitons, singular periodic solitons, and combined bright-dark solitons. The following year, Khalida Faisal et al. utilized the same SSEM to derive pure-cubic optical solitons for the Schrödinger equation that featured three different types of nonlinearities. By imposing specific constraints on certain parameters related to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE), they successfully obtained both bright and dark optical soliton solutions53. In 2024, Hamood Ur Rehman et al. applied the SSEM to analyze optical solitons within the (2 + 1)-dimensional coupled integrable NLSE. Their study concentrated particularly on the propagation and interaction of optical solitons across various media, such as multi-mode fibers and fiber arrays54. Previously, in 2016, Taher A. Nofal investigated the application of the SEM for solving NLPDEs and explored its practical implications. This research focused on deriving exact solutions for several prominent NLPDEs, including the Kadomtsev-Petviashvili (KP) equation, the (2 + 1)-dimensional breaking soliton equation, and the modified generalized Vakhnenko equation, using the SEM. Within the framework of SEM, the Bernoulli equation or the Riccati equation is utilized as a trial condition, allowing for the systematic derivation of exact solutions55.

We would like to point out that our SSEM and SEM has a number of benefits compared to other existing methods employed in solving nonlinear equations. First, they are more computationally efficient and allows for faster solutions. Second, it yields higher accuracy, particularly in problems involving strong nonlinearities. Finally, the approaches are more flexible in modeling various physical phenomena, and hence particularly useful in applications within areas like quantum mechanics and nonlinear optics57. Both the SSEM and the SEM are recognized as effective analytical techniques for solving NLPDEs, yet they exhibit significant differences in complexity, applicability, and methodology56. However, its complexity necessitates greater computational resources and a more sophisticated level of mathematical expertise from users. On the other hand, the SEM is defined by its straightforward and versatile nature. It utilizes basic functions, such as exponentials or trigonometric functions, which allows it to address a wider range of NLPDEs that exhibit moderate levels of nonlinearity. This characteristic makes the SEM particularly effective for solving problems related to heat transfer and wave propagation. Although the SSEM provides higher accuracy and greater flexibility for modeling complex systems, the SEM is generally simpler to implement and places fewer demands on computational resources58. Ultimately, the decision to use either the SSEM or the SEM is determined by factors including the complexity of the problem at hand, the desired precision of the solution, and the ease of implementation for the analyst. In this context, a novel three-dimensional, second-order nonlinear wave equation was introduced by Sakovich59, which can be expressed as follows:

The nonlinear wave equation has multisoliton solutions that simultaneously satisfy the fifth-order KdV equation and the KdV equation. Eq.(1) was extended by Wazwaz to produce the subsequent equation60:

Wazwaz et al. developed a brand-new (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation to explain the propagation of nonlinear waves. The Painlevé integrability of the recently determined equation was verified by using the truncation expansion method61.

where two new terms, \(f_{zz}\) and \(ff_{xx}\), have been introduced. The term \(f_{zz}\) represents the second-order dispersion effect in the \(z\)-direction, capturing the dispersion dynamics that occur as waves propagate along this axis. Meanwhile, the term \(ff_{xx}\) signifies the second-order dispersion along the \(x\)-axis, while also accounting for the nonlinear effects represented by the function \(f\). This inclusion allows for a more comprehensive modeling of wave behavior, incorporating both dispersive and nonlinear characteristics in different spatial directions.

The (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation models the dynamics of nonlinear wave propagation in diverse physical systems such as nonlinear media, plasma, and fluid mechanics. With its nonlinear nature, it facilitates investigation into effects such as solitons and shock waves that propagate without changing shape. The equation models the balance between nonlinearity and dispersion, providing insight into wave stability and interaction processes within a four-dimensional space time context.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section "Introduction" provides a detailed introduction to the paper. Section "Analysis of the methods" outlines the analysis for both the SSEM and the SEM. In Section "Applications", we discuss the applications of both methods. Section "Modulation instability (MI)" analyzes the modulation instability associated with the proposed model. Section "Results and discussion" presents the results along with graphical representations. Finally, we conclude the paper in Section "Conclusion".

Analysis of the methods

In this article, we aim to examine the soliton solution of Eq. (3) by employing the following two effective techniques: the SSEM62,63 and the SEM64. Let us introduce the NLPDEs that follows

where \(H\) be a polynomial that depends on the unknown function \(f(x, y, z, t)\) and its partial derivatives. In this context, \(f\) represents a function that varies with respect to the spatial variables \(x, y, z\) and the time variable \(t\). Additionally, we can consider a wave transformation to analyze the propagation of this function.

Eq. (4) is transformed into the following ODE using the transformation.

where \(F'\) represents \(\frac{dF}{d\xi }\).

The Sardar sub-equation method

The conditions governing the operation of the SSEM are outlined as follows. One approach to solving Eq. (3) is to reformulate it as follows:

where

here \(\theta\) and \(\rho\) are real constants. Eq. (8) displays the solutions as

Case-1:

If \(\rho >0\) and \(\theta =0\), we have

where \(sech_{mn}(\xi )=\frac{2}{m e^{\xi }+n e^{-\xi }},~csch_{mn}(\xi )=\frac{2}{m e^{\xi }-n e^{-\xi }}\).

Case-2:

If \(\rho <0\) and \(\theta =0\), we have

where \(\sec _{mn}(\xi )=\frac{2}{m e^{\iota \xi }+n e^{-\iota \xi }},~\csc _{mn}(\xi )=\frac{2\iota }{m e^{\iota \xi }-n e^{-\iota \xi }}\).

Case-3:

If \(\rho <0\) and \(\theta =\frac{\rho ^2}{4}\), we have

where \(tanh_{mn}=\frac{{me}^{\xi }-{ne}^{-\xi }}{{me}^{\xi }+{ne}^{-\xi }},~coth_{mn}=\frac{{me}^{\xi }+{ne}^{-\xi }}{{me}^{\xi }-{ne}^{-\xi }}\).

Case-4:

If \(\rho >0\) and \(\theta =\frac{{\rho }^2}{4}\), we have

where \(tan_{mn}=-\iota \frac{{me}^{\iota \xi }-{ne}^{-\iota \xi }}{{me}^{\iota \xi }+{ne}^{-\iota \xi }},~cot_{{mn}}=\iota \frac{{me}^{\iota \xi }+{ne}^{-\iota \xi }}{{me}^{\iota \xi }-{ne}^{-\iota \xi }}\).

The simple equation method

Suppose the solution of the NLODE of Eq. (3) that can be expanded in series as follows55:

In this context, the constants \(b_i\) take on values from \(0\) to \(N\) (where \(i = 0, 1, 2, \ldots , N\)) and will be defined in a future stage of our work. The integer \(N\) is a positive quantity that will be determined through the application of the balancing principle to Eq. (3). The function \(G(\xi )\) represents a category of functions that satisfy the governing equations. For our analysis, we will focus on the Bernoulli and Riccati equations, which will serve as the foundational equations for our study. These equations are well-recognized as NLPDEs, and their solutions can be expressed using elementary functions. Specifically, the Bernoulli equation can be formulated as follows:

where \(c_0,~c_1\), and \(c_2\) are constants and when \(c_0=0\) Eq. (30) converts into a Bernoulli Equation and solutions are:

when \(c_1=0\) Eq. (30) changes into a Riccati Equation and has following exact solutions:

Applications

By applying the transformation presented in Eq. (5), Eq. (3) is converted to

Application of Sardar sub-equation method

By applying the balancing principle to Eq. (29), we find that for \(N=2\), Eq. (7) simplifies to:

By substituting Eq. (30) into Eq. (29) while utilizing the information provided in Eq. (8), we establish an algebraic system. This is accomplished by equating each of the coefficients derived from the resulting expression to zero. This process ensures that we capture the necessary conditions for the equations to hold true, ultimately leading to a solvable system of equations based on the coefficients involved.

where

\(\begin{array}{l}{D_0} = 8{\alpha ^4}\delta _2^2{\theta ^2} + 12{\alpha ^2}\delta _0^2{\delta _2}\theta + 2{\alpha ^2}{\delta _2}\theta + 2{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _2}\theta + 2\alpha \beta {\delta _2}\theta \\+ 4\alpha \beta {\delta _0}{\delta _2}\theta + 2\alpha \gamma {\delta _2}\theta - 2\alpha {\delta _2}\theta \kappa + 2{\beta ^2}{\delta _2}\theta + 2\beta \gamma {\delta _2}\theta + 2{\gamma ^2}{\delta _2}\theta \end{array}\),

\(\begin{array}{l}{D_1} = 8{\alpha ^4}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\theta \rho + 2{\alpha ^2}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\theta + 24{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\theta + 6{\alpha ^2}\delta _0^2{\delta _1}\rho + {\alpha ^2}{\delta _1}\rho \\+ {\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _1}\rho + 4\alpha \beta {\delta _1}{\delta _2}\theta + \alpha \beta {\delta _1}\rho + 2\alpha \beta {\delta _0}{\delta _1}\rho + \alpha \gamma {\delta _1}\rho - \alpha {\delta _1}\kappa \rho \\+ {\beta ^2}{\delta _1}\rho + \beta \gamma {\delta _1}\rho + {\gamma ^2}{\delta _1}\rho ,\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{D_2} = 32{\alpha ^4}\delta _2^2\theta \rho + 2{\alpha ^4}\delta _1^2{\rho ^2} + 2{\alpha ^2}\delta _2^2\theta + 24{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}\delta _2^2\theta + 12{\alpha ^2}\delta _1^2{\delta _2}\theta \\+ {\alpha ^2}\delta _1^2\rho + 12{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}\delta _1^2\rho + 24{\alpha ^2}\delta _0^2{\delta _2}\rho + 4{\alpha ^2}{\delta _2}\rho + 4{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _2}\rho \\+ 4\alpha \beta \delta _2^2\theta + 2\alpha \beta \delta _1^2\rho + 4\alpha \beta {\delta _2}\rho + 8\alpha \beta {\delta _0}{\delta _2}\rho + 4\alpha \gamma {\delta _2}\rho \\- 4\alpha {\delta _2}\kappa \rho + 4{\beta ^2}{\delta _2}\rho + 4\beta \gamma {\delta _2}\rho + 4{\gamma ^2}{\delta _2}\rho ,\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{D_3} = 16{\alpha ^4}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\theta + 16{\alpha ^4}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}{\rho ^2} + 24{\alpha ^2}{\delta _1}\delta _2^2\theta + 6{\alpha ^2}\delta _1^3\rho + 5{\alpha ^2}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\rho \\+ 60{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _1}{\delta _2}\rho + 12{\alpha ^2}\delta _0^2{\delta _1} + 2{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _1} + 2{\alpha ^2}{\delta _1} + 10\alpha \beta {\delta _1}{\delta _2}\rho \\+ 2\alpha \beta {\delta _1} + 4\alpha \beta {\delta _0}{\delta _1} + 2\alpha \gamma {\delta _1} - 2\alpha {\delta _1}\kappa + 2{\beta ^2}{\delta _1} + 2\beta \gamma {\delta _1} + 2{\gamma ^2}{\delta _1},\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{D_4} = 48{\alpha ^4}\delta _2^2\theta + 32{\alpha ^4}\delta _2^2{\rho ^2} + 8{\alpha ^4}\delta _1^2\rho + 12{\alpha ^2}\delta _2^3\theta + 4{\alpha ^2}\delta _2^2\rho \\+ 48{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}\delta _2^2\rho + 36{\alpha ^2}\delta _1^2{\delta _2}\rho + 24{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}\delta _1^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}\delta _1^2 + 36{\alpha ^2}\delta _0^2{\delta _2}\\+ 6{\alpha ^2}{\delta _0}{\delta _2} + 6{\alpha ^2}{\delta _2} + 8\alpha \beta \delta _2^2\rho + 4\alpha \beta \delta _1^2 + 6\alpha \beta {\delta _2} + 12\alpha \beta {\delta _0}{\delta _2}\\+ 6\alpha \gamma {\delta _2} - 6\alpha {\delta _2}\kappa + 6{\beta ^2}{\delta _2} + 6\beta \gamma {\delta _2} + 6{\gamma ^2}{\delta _2},\end{array}\)

\(D_5=56 \alpha ^4 \delta _1 \delta _2 \rho +54 \alpha ^2 \delta _1 \delta _2^2 \rho +12 \alpha ^2 \delta _1^3+96 \alpha ^2 \delta _0 \delta _1 \delta _2+8 \alpha ^2 \delta _1 \delta _2+16 \alpha \beta \delta _1 \delta _2,\)

\(D_6=96 \alpha ^4 \delta _2^2 \rho +8 \alpha ^4 \delta _1^2+24 \alpha ^2 \delta _2^3 \rho +72 \alpha ^2 \delta _0 \delta _2^2+6 \alpha ^2 \delta _2^2+60 \alpha ^2 \delta _1^2 \delta _2+12 \alpha \beta \delta _2^2,\)

\(D_7=48 \alpha ^4 \delta _1 \delta _2+84 \alpha ^2 \delta _1 \delta _2^2,\)

\(D_8=72 \alpha ^4 \delta _2^2+36 \alpha ^2 \delta _2^3.\)

By setting all coefficients equal to zero

When these algebraic equations are solved, we obtain

Using the cases described in Eqs. (9-22), we obtain distinct solutions, and the results are as follows:

Case-1:

If \(\rho >0\) and \(\theta =0\), we have

Case-2:

If \(\rho <0\) and \(\theta =0\), we have

Case-3:

If \(\rho <0\) and \(\theta =\frac{\rho ^2}{4}\), we have

Case-4:

If \(\rho >0\) and \(\theta =\frac{{\rho }^2}{4}\), we have

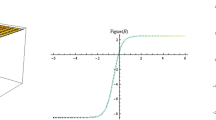

Visual representation of the bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (33) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.9,~\alpha =0.8,~\gamma =1.5,\)\(\,~\delta _0=0.5,~\theta =2.8,~m=1.3,~n=0.99,~y=0.9\)\(\,~m=1.3,~n=0.99,~y=0.9\), and \(z=0.3\).

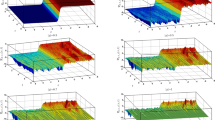

Visual representation of the dark soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (34) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.5,~\alpha =0.66,~\gamma =1.9,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.2,~\theta =1.8,\)\(\,~m=1.5,~n=0.6,~y=1.1\), and \(z=1.2\).

Visual representation of the singular soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (37) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.4,~\alpha =1.3,~\gamma =0.9,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.7,~\theta =0.55,\)\(\,~m=0.8,~n=0.7,~y=1.9\), and \(z=2.3\).

Visual representation of the periodic bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (38) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.4,~\alpha =0.55,~\gamma =0.77,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.5,~\theta =2.1,\)\(\,~m=2.3,~n=1.9,~y=0.9\), and \(z=0.3\).

Visual representation of the periodic bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (39) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.3,~\alpha =0.2,~\gamma =0.5,\)\(\,~\delta _0=0.9,~\theta =0.2,\)\(\,~m=0.5,~n=0.8,~y=0.3\), and \(z=0.6\).

Visual representation of the singular periodic soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (40) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.9,~\alpha =1.2,~\gamma =0.7,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.1,~\theta =1.2,\)\(\,~m=0.9,~n=0.8,~y=1.6\), and \(z=1.4\).

Visual representation of the bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (41) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.1,~\alpha =0.3,~\gamma =0.8,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.3,~\theta =0.2,\)\(\,~m=1.2,~n=1.5,~y=0.6\), and \(z=0.4\).

Visual representation of the cuspons soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (42) using the SSEM at \(\rho =1.4,~\alpha =0.5,~\gamma =0.6,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.1,~\theta =0.6,\)\(\,~m=1.1,~n=1.3,~y=1.1\), and \(z=0.4\).

Visual representation of the bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (44) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.4,~\alpha =0.6,~\gamma =0.8,\)\(\,~\delta _0=0.5,~\theta =0.2,\)\(\,~m=0.1,~n=0.3,~y=0.8\), and \(z=0.7\).

Visual representation of the periodic soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (45) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.1,~\alpha =0.9,~\gamma =1.2,\)\(\,~\delta _0=2.7,~\theta =0.2,\)\(\,~m=1.8,~n=2.7,~y=0.6\), and \(z=0.7\).

Visual representation of the periodic bright soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (46) using the SSEM at \(\rho =0.2,~\alpha =0.5,~\gamma =1.5,\)\(\,~\delta _0=1.5,~\theta =1.5,\)\(\,~m=2.5,~n=1.8,~y=0.4\), and \(z=0.9\).

Application of simple equation method

By applying the balancing principle to Eq. (29), we find that for \(N=2\), Eq. (23) simplifies to:

By substituting Eq. (47) into Eq. (29) and utilizing Eq. (24), we form an algebraic system by setting all coefficients equal to zero.

where

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_0} = 8{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_0^4 + 2{\alpha ^4}b_1^2c_0^2c_1^2 + 8{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^3{c_1} + 12{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_2}c_0^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_2}c_0^2\\+ 2{\alpha ^2}{b_2}c_0^2 + 6{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + {\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + {\alpha ^2}{b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + 2\alpha \beta {b_2}c_0^2\\+ 4\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_2}c_0^2 + \alpha \beta {b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + 2\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + 2\alpha {b_2}\gamma c_0^2 + \alpha {b_1}\gamma {c_0}{c_1}\\- 2\alpha {b_2}c_0^2\kappa - \alpha {b_1}{c_0}{c_1}\kappa + 2{\beta ^2}{b_2}c_0^2 + {\beta ^2}{b_1}{c_0}{c_1} + 2\beta {b_2}\gamma c_0^2 + \beta {b_1}\gamma {c_0}{c_1}\\+ 2{b_2}{\gamma ^2}c_0^2 + {b_1}{\gamma ^2}{c_0}{c_1}\end{array}\),

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_1} = 4{\alpha ^4}b_1^2{c_0}c_1^3 + 32{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^2c_1^2 + 48{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_0^3{c_1} + 16{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^3{c_2} + 8{\alpha ^4}b_1^2c_0^2{c_1}{c_2}\\+ 24{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^2 + 6{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_1}c_1^2 + {\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}c_1^2 + {\alpha ^2}{b_1}c_1^2 + 12{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_1^2{c_0}{c_1}\\+ {\alpha ^2}b_1^2{c_0}{c_1} + 36{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 6{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 6{\alpha ^2}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 12{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_1}{c_0}{c_2}\\+ 2{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{c_0}{c_2} + 2{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{c_0}{c_2} + 4\alpha \beta {b_1}{b_2}c_0^2 + \alpha \beta {b_1}c_1^2 + 2\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_1}c_1^2 + 2\alpha \beta b_1^2{c_0}{c_1}\\+ 6\alpha \beta {b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 12\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 2\alpha \beta {b_1}{c_0}{c_2} + 4\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_1}{c_0}{c_2} + \alpha {b_1}\gamma c_1^2 + 6\alpha {b_2}\gamma {c_0}{c_1}\\+ 2\alpha {b_1}\gamma {c_0}{c_2} - \alpha {b_1}c_1^2\kappa - 6\alpha {b_2}{c_0}{c_1}\kappa - 2\alpha {b_1}{c_0}{c_2}\kappa + {\beta ^2}{b_1}c_1^2 + 6{\beta ^2}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1}\\+ 2{\beta ^2}{b_1}{c_0}{c_2} + \beta {b_1}\gamma c_1^2 + 6\beta {b_2}\gamma {c_0}{c_1} + 2\beta {b_1}\gamma {c_0}{c_2} + {b_1}{\gamma ^2}c_1^2 + 6{b_2}{\gamma ^2}{c_0}{c_1}\\+ 2{b_1}{\gamma ^2}{c_0}{c_2},\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_2} = 2b_1^2c_1^4{\alpha ^4} + 40{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}c_1^3{\alpha ^4} + 104b_2^2c_0^2c_1^2{\alpha ^4} + 8b_1^2c_0^2c_2^2{\alpha ^4} + 64b_2^2c_0^3{c_2}{\alpha ^4}\\+ 20b_1^2{c_0}c_1^2{c_2}{\alpha ^4} + 104{b_1}{b_2}c_0^2{c_1}{c_2}{\alpha ^4} + 24{b_0}b_2^2c_0^2{\alpha ^2} + 2b_2^2c_0^2{\alpha ^2} + 12b_1^2{b_2}c_0^2{\alpha ^2}\\+ 12{b_0}b_1^2c_1^2{\alpha ^2} + b_1^2c_1^2{\alpha ^2} + 24b_0^2{b_2}c_1^2{\alpha ^2} + 4{b_0}{b_2}c_1^2{\alpha ^2} + 4{b_2}c_1^2{\alpha ^2} + 6b_1^3{c_0}{c_1}{\alpha ^2}\\+ 84{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1}{\alpha ^2} + 7{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1}{\alpha ^2} + 24{b_0}b_1^2{c_0}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 2b_1^2{c_0}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 48b_0^2{b_2}{c_0}{c_2}{\alpha ^2}\\+ 8{b_0}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 8{b_2}{c_0}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 18b_0^2{b_1}{c_1}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 3{b_0}{b_1}{c_1}{c_2}{\alpha ^2} + 3{b_1}{c_1}{c_2}{\alpha ^2}\\+ 4\beta b_2^2c_0^2\alpha + 2\beta b_1^2c_1^2\alpha + 4\beta {b_2}c_1^2\alpha + 4\gamma {b_2}c_1^2\alpha - 4\kappa {b_2}c_1^2\alpha + 8\beta {b_0}{b_2}c_1^2\alpha \\+ 14\beta {b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1}\alpha + 4\beta b_1^2{c_0}{c_2}\alpha + 8\beta {b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\alpha + 8\gamma {b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\alpha - 8\kappa {b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\alpha \\+ 16\beta {b_0}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\alpha + 3\beta {b_1}{c_1}{c_2}\alpha + 3\gamma {b_1}{c_1}{c_2}\alpha - 3\kappa {b_1}{c_1}{c_2}\alpha + 6\beta {b_0}{b_1}{c_1}{c_2}\alpha \\+ 4{\beta ^2}{b_2}c_1^2 + 4{\gamma ^2}{b_2}c_1^2 + 4\beta \gamma {b_2}c_1^2 + 8{\beta ^2}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2} + 8{\gamma ^2}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2} + 8\beta \gamma {b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\\+ 3{\beta ^2}{b_1}{c_1}{c_2} + 3{\gamma ^2}{b_1}{c_1}{c_2} + 3\beta \gamma {b_1}{c_1}{c_2},\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_3} = 16{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_1^4 + 96{\alpha ^4}b_2^2{c_0}c_1^3 + 80{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_0^2c_2^2 + 32{\alpha ^4}b_1^2{c_0}{c_1}c_2^2 + 12{\alpha ^4}b_1^2c_1^3{c_2}\\+ 176{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}c_1^2{c_2} + 272{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_0^2{c_1}{c_2} + 24{\alpha ^2}{b_1}b_2^2c_0^2 + 6{\alpha ^2}b_1^3c_1^2 + 60{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}c_1^2\\+ 5{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{b_2}c_1^2 + 12{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_1}c_2^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}c_2^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}{b_1}c_2^2 + 72{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_2^2{c_0}{c_1} + 6{\alpha ^2}b_2^2{c_0}{c_1}\\+ 48{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{b_2}{c_0}{c_1} + 12{\alpha ^2}b_1^3{c_0}{c_2} + 120{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2} + 10{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2} + 36{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_1^2{c_1}{c_2}\\+ 3{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{c_1}{c_2} + 60{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 10{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 10{\alpha ^2}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 10\alpha \beta {b_1}{b_2}c_1^2\\+ 2\alpha \beta {b_1}c_2^2 + 4\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_1}c_2^2 + 12\alpha \beta b_2^2{c_0}{c_1} + 20\alpha \beta {b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_2} + 6\alpha \beta b_1^2{c_1}{c_2}\\+ 10\alpha \beta {b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 20\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 2\alpha {b_1}\gamma c_2^2 + 10\alpha {b_2}\gamma {c_1}{c_2} - 2\alpha {b_1}c_2^2\kappa \\- 10\alpha {b_2}{c_1}{c_2}\kappa + 2{\beta ^2}{b_1}c_2^2 + 10{\beta ^2}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 2\beta {b_1}\gamma c_2^2 + 10\beta {b_2}\gamma {c_1}{c_2} + 2{b_1}{\gamma ^2}c_2^2\\+ 10{b_2}{\gamma ^2}{c_1}{c_2},\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_4} = 32{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_1^4 + 16{\alpha ^4}b_1^2{c_0}c_2^3 + 176{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_0^2c_2^2 + 26{\alpha ^4}b_1^2c_1^2c_2^2 + 248{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}{c_1}c_2^2\\+ 88{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_1^3{c_2} + 368{\alpha ^4}b_2^2{c_0}c_1^2{c_2} + 12{\alpha ^2}b_2^3c_0^2 + 48{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_2^2c_1^2 + 4{\alpha ^2}b_2^2c_1^2\\+ 36{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{b_2}c_1^2 + 24{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_1^2c_2^2 + 2{\alpha ^2}b_1^2c_2^2 + 36{\alpha ^2}b_0^2{b_2}c_2^2 + 6{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_2}c_2^2\\+ 6{\alpha ^2}{b_2}c_2^2 + 78{\alpha ^2}{b_1}b_2^2{c_0}{c_1} + 96{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_2^2{c_0}{c_2} + 8{\alpha ^2}b_2^2{c_0}{c_2} + 72{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{b_2}{c_0}{c_2}\\+ 18{\alpha ^2}b_1^3{c_1}{c_2} + 156{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 13{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 8\alpha \beta b_2^2c_1^2 + 4\alpha \beta b_1^2c_2^2\\+ 6\alpha \beta {b_2}c_2^2 + 12\alpha \beta {b_0}{b_2}c_2^2 + 16\alpha \beta b_2^2{c_0}{c_2} + 26\alpha \beta {b_1}{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 6\alpha {b_2}\gamma c_2^2\\- 6\alpha {b_2}c_2^2\kappa + 6{\beta ^2}{b_2}c_2^2 + 6\beta {b_2}\gamma c_2^2 + 6{b_2}{\gamma ^2}c_2^2,\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_5} = 112{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}{c_0}c_2^3 + 24{\alpha ^4}b_1^2{c_1}c_2^3 + 176{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}c_1^2c_2^2 + 464{\alpha ^4}b_2^2{c_0}{c_1}c_2^2\\+ 160{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_1^3{c_2} + 54{\alpha ^2}{b_1}b_2^2c_1^2 + 12{\alpha ^2}b_1^3c_2^2 + 96{\alpha ^2}{b_0}{b_1}{b_2}c_2^2 + 8{\alpha ^2}{b_1}{b_2}c_2^2\\+ 36{\alpha ^2}b_2^3{c_0}{c_1} + 108{\alpha ^2}{b_1}b_2^2{c_0}{c_2} + 120{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_2^2{c_1}{c_2} + 10{\alpha ^2}b_2^2{c_1}{c_2}\\+ 96{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{b_2}{c_1}{c_2} + 16\alpha \beta {b_1}{b_2}c_2^2 + 20\alpha \beta b_2^2{c_1}{c_2},\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{E_6} = 8{\alpha ^4}b_1^2c_2^4 + 192{\alpha ^4}b_2^2{c_0}c_2^3 + 152{\alpha ^4}{b_1}{b_2}{c_1}c_2^3 + 296{\alpha ^4}b_2^2c_1^2c_2^2\\+ 24{\alpha ^2}b_2^3c_1^2 + 72{\alpha ^2}{b_0}b_2^2c_2^2 + 6{\alpha ^2}b_2^2c_2^2 + 60{\alpha ^2}b_1^2{b_2}c_2^2 + 48{\alpha ^2}b_2^3{c_0}{c_2}\\+ 138{\alpha ^2}{b_1}b_2^2{c_1}{c_2} + 12\alpha \beta b_2^2c_2^2,\end{array}\)

\(E_7=48 \alpha ^4 b_1 b_2 c_2^4+240 \alpha ^4 b_2^2 c_1 c_2^3+84 \alpha ^2 b_1 b_2^2 c_2^2+60 \alpha ^2 b_2^3 c_1 c_2,\)

\(E_8=72 \alpha ^4 b_2^2 c_2^4+36 \alpha ^2 b_2^3 c_2^2.\)

By setting all coefficients equal to zero

The solution set we obtain is

For Bernoulli Equation when \(c_0=0\)

Case-1:

Case-2:

When \(p<0\)

For Riccati equation, when \(c_1=0\) the solutions we obtain are

Case-3:

Case-4:

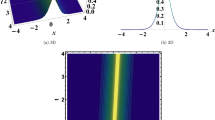

Visual representation of the compacton soliton by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (50) using the SEM at \(b_0=0.6,~c_1=1.1,~c_2=0.7,~b_2=1.5,\)\(\,~\xi _0=0.8,~\alpha =0.5,~\beta =1.2,\)\(\,~\gamma =2.2,~\kappa =0.9,~z=0.5\), and \(y=0.8\).

Visual representation of the dark soliton solution by using 3D, contour, density, and 2D graphs respectively, that correspond to Eq. (53) using the SEM at \(b_0=0.8,~c_2=1.7,~b_2=0.1,~\xi _0=0.8,\)\(\,~c_0=0.78,~\alpha =0.66,~\beta =1.2,\)\(\,~\gamma =0.7,~\kappa =1.4,~z=1.5,~y=0.55\), and \(s=1.0\).

Modulation instability (MI)

modulation instability (MI) refers to the tendency of a steady-state solution to become unstable in the presence of small perturbations. In essence, while the system may initially appear to be in a stable state, any small disturbance can grow exponentially over time, leading to significant changes in the system’s behavior. This instability arises when the dispersion, which tends to smooth out disturbances, is counteracted by the nonlinearities present in the system, which can amplify these disturbances. In analyzing the governing equation through linear stability methods, we examine how disturbances evolve and identify conditions under which MI occurs. By studying eigenvalues and the associated growth rates of perturbations, we can ascertain the stability of the steady-state solutions and understand the critical roles that nonlinearity and dispersion play in instigating modulation instability. This detailed exploration of MI enables us to predict the potential development of complex structures and patterns within the system, further enriching our understanding of nonlinear dynamics. In the context of steady-state modulation, certain nonlinear systems can demonstrate instability as a result of the interaction between nonlinearity and dispersive effects. This section of the analysis utilizes a linear stability approach to investigate the phenomenon of MI associated with the governing equation65.

Here P denotes the normalized optical power. Now, putting Eq. (54) in Eq. (3), we get,

Assume that the solution to Eq. (55) has the following form

In this context, \(\kappa\) denotes the frequency of the perturbation, while \(p\) represents the normalized wave number. By substituting Eq. (56) into Eq. (55), we derive the following dispersion relation.

By analyzing the dispersion relation for the variable \(\kappa\), Eq. (57) produces

The dispersion relation obtained is expected to predict the stable steady state solution. In case of a real value for \(\kappa\), the influence of small perturbation makes the steady state stable. However, in case \(\kappa\) is not real, the steady state becomes unstable and gradually grows the perturbation.

Results and discussion

In this research, we have utilized two novel approaches, namely the SSEM and the SEM, to address the (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation. This section provides visual representations of a range of soliton solutions that emerge within the system under investigation. 3D, 2D, contour, and density plots have been used to graphically present the outcomes, offering a detailed visualization of the data. Every type of plot is used for a different purpose: 3D plots show relationships in a spatial manner, while 2D plots make intricate data easier to interpret. Contour plots depict the interactions and gradients between variables, while density plots highlight the distribution and density of data. Together, these plots give a better and more complete picture of the data by presenting both value interactions and underlying patterns. The newly formulated (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation has been the subject of extensive examination through various methodologies. In this segment, we aim to compare our results with those obtained from previous studies that employed different techniques. Specifically, we juxtapose our findings with those derived from the exp\((-\psi (\eta ))\) expansion method66 and the New Modified Extended Direct Algebraic (NMEDA) technique. This comparison will highlight the effectiveness and insights provided by our approaches in relation to these alternative methods in solving the Sakovich equation67.

-

Khalid K. Ali et al.68 investigated soliton solutions for the (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation, utilizing the exp\((- \psi (\eta ))\) expansion method in conjunction with the Bernoulli sub-ODE method. Their analysis resulted in a diverse array of solution types, encompassing bright solitons, dark solitons, periodic solitons, exponential solitons, and singular solitons. Furthermore, they provided visual representations of these soliton solutions, which are depicted in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional formats. These graphical illustrations facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the different behaviors and characteristics of the solitons identified in their study.

-

Muhammad Younis et al.69 conducted a comprehensive investigation into various wave structures associated with the Sakovich equation. Their research uncovered a range of wave configurations, including singular solitary waves and their combinations such as shock waves, shock-singular waves, complex solitary-shock waves, and periodic-singular waves. Notably, the derivation process also revealed rational solutions, which further contributed to the breadth of solutions identified. These findings were achieved through the application of the NMEDA technique, demonstrating the method’s versatility and effectiveness in tackling the intricate nature of the Sakovich equation. The results underscore the ability of the NMEDA technique to yield a diverse spectrum of wave solutions, thereby enhancing the understanding of the dynamics described by the Sakovich equation.

-

In this research paper, we have successfully derived a broad spectrum of soliton solutions encompassing various forms, including bright solitons, dark solitons, kink solitons, cuspon solitons, singular solitons, singular periodic solitons, and periodic solitons. These solutions are effectively illustrated through a variety of visual representations, including three-dimensional plots, contour plots, density plots, and two-dimensional plots. The methodologies employed in this study include both the SSEM and SEM techniques. Notably, while some of our findings exhibit differences compared to those documented in52, we discovered that modifications to certain parameters could yield results that are more consistent with the previous study. It is important to highlight that the contributions presented in this article are not only practical and succinct but are also articulated in a clear manner. This clarity enhances their understanding, particularly in the context of applications involving nonlinear waves. The comprehensive approach taken in this study facilitates a deeper insight into the behavior of soliton solutions within the framework of nonlinear dynamics.

The soliton solutions are illustrated in Figs. (1-14). Fig. (1) displays the bright soliton derived from Eq. (33). Fig. (2) showcases the dark soliton resulting from Eq. (34). In Fig. (3), the singular soliton originating from Eq. (37) is presented. Figs (4) and (5) illustrate the periodic bright soliton resulting from Eqs. (38) and (39), respectively. Fig. (15) reveals the singular periodic soliton derived from Eq. (40). Fig. (7) displays another bright soliton originating from Eq. (41). Fig. (8) depicts the cuspons that arise from Eq. (42). Fig. (9) shows the bright soliton that emerges from Eq. (44), while Fig. (10) illustrates the periodic from the same equation. Fig. (11) showcases another bright soliton resulting from Eq. (46). Fig. (12) presents the compacton soliton originating from Eq. (50). Fig. (13) depicts the anti-kink waves arising from Eq. (51), and finally, Fig. (14) illustrates the dark soliton derived from Eq. (53).

Solitons are remarkable for their unique capability to maintain their amplitude, velocity, and shape as they propagate through a medium. The solutions discussed in this study hold considerable physical significance and exhibit a variety of characteristics. For example, a dark soliton is defined by having an intensity that is lower than that of the surrounding background. In contrast to conventional pulses, which carry energy, a dark soliton represents a localized area within a continuous temporal beam where energy density is effectively reduced to zero70. On the other hand, periodic wave solutions are characterized by their repetitive and continuous waveform patterns, which define key properties such as wavelength and frequency71. Specifically, the period of a waveform refers to the duration required to complete a full cycle, while frequency describes the number of cycles that occur in a given time frame, typically measured in cycles per second. The concept of singular solitons is intrinsically linked to solitary waves, especially when the peak of the solitary wave is situated at an imaginary position72. This makes the investigation of singular solitons particularly significant, as these solutions, characterized by pronounced spikes, may offer valuable insights into the mechanisms that contribute to the formation of rogue waves. Dark solitons are particularly distinctive due to their localized dips within a stable continuous-wave background, demonstrating a unique interplay between energy levels. In comparison to bright solitons, dark solitons generated in fiber lasers are noted for their enhanced stability against noise and exhibit a lower sensitivity to energy losses. Kink waves, by contrast, are defined by their transitions between specific asymptotic states. These waves can either ascend or descend and ultimately reach a steady value as they extend to infinitely large distances73. Moreover, cuspon solutions are identified by the presence of sharp cusps at their peaks74. Compactons, on the other hand, are characterized by having finite spatial support; each compacton behaves as a soliton that is confined within a specific spatial core75. Given these characteristics, the various soliton solutions highlighted in this study not only showcase the diversity of wave behavior but also underscore their potential relevance in understanding complex nonlinear phenomena.

Advantages and limitations of the methods presented in this paper

Sardar Sub Equation Method (SSEM) and Simple Equation Method (SEM) are both useful tools to tackle nonlinear evolution equations (NLEEs). SSEM is effective in producing various solutions such as solitary and periodic waves, while SEM is simple and easy to use for scientists at all levels. They provide a potent method for investigation of complicated physical phenomena, the deepening of knowledge on nonlinear dynamics.

Advantages

Unlike the generalized projective Riccati and improved tan\((\frac{\varphi (\eta )}{2})\)-expansion methods, which are effective only for ODEs of order three or lower, the SSEM handles equations up to fourth order by introducing more arbitrary constants. This overcomes the issue of having more equations than unknowns, simplifies computation, and ensures consistency. The method’s efficiency is demonstrated by obtaining new soliton solutions for higher-order nonlinear models, with potential applications in optical fiber technology. The SEM has a number of advantages, such as simplicity, allowing researchers of any proficiency to use it successfully. SEM gives precise solutions to nonlinear evolution equations with minimal computational effort, making it easily applicable for regular use. SEM can also distinguish between various forms of solutions, like solitary waves, making it useful in different fields.

Limitations

Analytical approaches may become difficult or unfeasible when FCNLSEs exhibit significant nonlinearities or intricate boundary conditions. Numerical methods may be more suitable in these situations. The choice of parameters and starting conditions can have a significant impact on the methods’ efficacy; therefore, careful adjustment is necessary because the outcomes may differ depending on these decisions.

Conclusion

In this paper, we investigate the application of the SSEM and the SEM to extract soliton solutions from the novel three-and-a-half-dimensional Sakovich equation. Our aim is to evaluate the equation’s effectiveness in capturing additional dispersion and nonlinear phenomena that can be applied in various practical contexts. By utilizing these methodologies, we have successfully identified a diverse array of solitary wave solutions, which include exponential, trigonometric, and hyperbolic forms. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the nonlinear dynamics associated with this newly formulated equation. The transformation of this significant physical model into an ODE is achieved through a wave transformation, which facilitates further analytical exploration. The techniques we used have several advantages, such as ease of use, accuracy, and ability to reduce computational requirements, showing their utility in various areas. By applying these methods, we were able to produce many new soliton solutions through symbolic computation using Mathematica. The solutions exhibit various wave patterns, i.e., dark solitons, bright solitons, singular solitons, compactons, periodic solitons, kink solitons, cuspons, and singular periodic solitons76. To analyze the dynamics of these solutions, we conducted comprehensive examinations utilizing three-dimensional, two-dimensional, contour, and density plots. Additionally, we assessed the MI of the governing model to provide insights into the stability characteristics of the wave solutions. The groundbreaking discoveries presented in this study offer substantial motivation for future research that explores a wide range of advanced nonlinear concepts. This methodological approach not only demonstrates its reliability but also significantly reduces computational complexity, thereby enhancing its applicability across diverse domains. The implementation of these techniques has uncovered a rich variety of solitonic wave structures, which function as traveling wave solutions, and opens avenues for further investigations into the intricate nature of nonlinear wave phenomena.

Soliton theory has found broad application in many areas of science and engineering, including fluid mechanics, plasma physics, nonlinear optics, astrophysics, and molecular biology, where it plays a crucial role in solving sophisticated real-world issues. In fiber optics, for example, solitons play a key role in guaranteeing the long-distance, distortion-free transmission of digital information77. Dark solitons, which are intensity dips localized on a continuous wave background, are finding more and more applications in fields such as optical sensing, high-speed optical communication, and nonlinear optical systems, testifying to their versatility and technological importance78. Bright soliton solutions, which are intensity peaks localized, have been found to be crucial in physical systems like plasma environments and Bose-Einstein condensates. Specifically, periodic bright solitons play a critical role in oceanography and coastal engineering by assisting in rogue wave formation modeling and shallow water wave dynamics analysis79. Our study is valuable because it can help guide future investigations, particularly when applying these soliton solutions to enhance more effective communication systems and gain a better understanding of complex wave dynamics. Future studies will focus on examining these soliton forms in practical settings, such as enhancing data reliability in nonlinear optical devices and optical networks. This study contributes to the body of theory and opens up new avenues for creative engineering ideas in nonlinear dynamics. Based on our present results, our future work will investigate some specific issues to further reveal the dynamics of solitons. First, we will study the stability and dynamics of solitons in the framework of dispersive hydrodynamics, specially with emphasis on rogue waves and their applications to ocean engineering and safety of navigation. This entails exploring collisions of multi-solitons and how they might produce sudden changes in amplitude that could be harmful in aquatic ecosystems. We also intend to explore interactions between solitons in higher dimensions with the focus on applications in nonlinear optics where propagation of light in intricate media may cause emergent behavior to compromise signal integrity. We will also discuss the effects of external disturbances on soliton stability in Bose-Einstein condensates, especially under the influence of temperature fluctuations or external potentials, and these are particularly important for improvements in quantum technologies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Simpson, M. J. et al. Modelling count data with partial differential equation models in biology. J. Theor. Biol. 580, 111732 (2024).

Ganie, A. H. et al. New investigation of the analytical behaviors for some nonlinear PDEs in mathematical physics and modern engineering. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 9, 100608 (2024).

Khater, M. M. et al. On the interaction between (low & high) frequency of (ion-acoustic & Langmuir) waves in plasma via some recent computational schemes. Results in Physics 19, 103684 (2020).

Rezazadeh, H., Batool, F., Inc, M., Akinyemi, L. & Hashemi, M. S. Exact traveling wave solutions of generalized fractional Tzitz ica-type nonlinear evolution equations in nonlinear optics. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 55(6), 485 (2023).

Chen, S. J., Yin, Y. H. & Lü, X. Elastic collision between one lump wave and multiple stripe waves of nonlinear evolution equations. Commun. Nonlinear. Sci. Numer. Simul. 130, 107205 (2024).

Kumar, S. & Mohan, B. A direct symbolic computation of center-controlled rogue waves to a new Painlevé-integrable (3+ 1)-D generalized nonlinear evolution equation in plasmas. Nonlinear Dyn. 111(17), 16395–16405 (2023).

Ahmad, J., & Mustafa, Z. Multi soliton solutions and their wave propagation insights to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation via two expansion methods. Quantum Stud.: Math. Found. 1-17 (2024).

Ibrahim, R. W., Jalab, H. A., Karim, F. K., Alabdulkreem, E. & Ayub, M. N. A medical image enhancement based on generalized class of fractional partial differential equations. Quant. Imaging. Med. Surg. 12(1), 172 (2022).

Harris, P. J. The mathematical modelling of the motion of biological cells in response to chemical signals. Computational and Analytic Methods in Science and Engineering, 151-171 (2020).

Tazgan, T., Celik, E., Gülnur, Y. E. L., & Bulut, H. On Survey of the Some Wave Solutions of the Non-Linear Schrödinger Equation (NLSE) in Infinite Water Depth. Gazi University Journal of Science, 1-1 (2023).

Zhang, X., Zhu, H. & Kuo, L. H. A comparison study of the LMAPS method and the LDQ method for time-dependent problems. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 37(11), 1408–1415 (2013).

Hussain, R., Murtaza, J., Ahmad, J., Alkarni, S., & Shah, N. A. Dynamical perspective of sensitivity analysis and optical soliton solutions to the fractional Benjamin-Ono model. Results in Physics. 58 107453 (2024).

Akram, S. & Ahmad, J. Dynamical behaviors of analytical and localized solutions to the generalized Bogoyavlvensky-Konopelchenko equation arising in mathematical physics. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(3), 380 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Mustafa, Z., Hameed, M., Alkarni, S., & Shah, N. A. Dynamics characteristics of soliton structures of the new (3+ 1) dimensional integrable wave equations with stability analysis. Results in Physics, 107434 (2024).

Hossain, A. K. S. & Akbar, M. A. Multi-soliton solutions of the Sawada-Kotera equation using the Hirota direct method: Novel insights into nonlinear evolution equations. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100572 (2023).

El-Ganaini, S. & Kumar, S. Symbolic computation to construct new soliton solutions and dynamical behaviors of various wave structures for two different extended and generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equations using the new improved modified generalized sub-ODE proposed method. Math. Comput. Simul. 208, 28–56 (2023).

Hashemi, M. S. & Mirzazadeh, M. Optical solitons of the perturbed nonlinear Schrödinger equation using Lie symmetry method. Optik 281, 170816 (2023).

Nadeem, M. & He, J. H. He-Laplace variational iteration method for solving the nonlinear equations arising in chemical kinetics and population dynamics. J. Math. Chem. 59, 1234–1245 (2021).

Aziz, A., Das, A. & Ray, S. Scalar Perturbations of Gravitational Collapse under Homotopy Perturbation Method: A Critical Study on the Rectangular and Price Potential. Fortschritte der Physik 72(1), 2300029 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Mustafa, Z. & Habib, J. Analyzing dispersive optical solitons in nonlinear models using an analytical technique and its applications. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(1), 77 (2024).

Hossain, S., Rahman, M. M., Bashar, M. H., Biswas, S. & Roshid, M. M. Dynamical Structure of the Soliton Solution of M?Fractional (2+ 1)?Dimensional Heisenberg Ferromagnetic Spin Chain Model Through Advanced exp (- \(\phi\) (\(\xi\)))?Expansion Schemes in Mathematical Physics. J. Appl. Math. 2025(1), 5535543 (2025).

Bashar, M. H., Ghosh, S. & Rahman, M. M. Dynamical exploration of optical soliton solutions for M-fractional Paraxial wave equation. Plos one 19(2), e0299573 (2024).

Mawa, H. Z. et al. Soliton Solutions to the BA Model and (3+ 1)?Dimensional KP Equation Using Advanced exp (- \(\phi\) (\(\xi\)))?Expansion Scheme in Mathematical Physics. Math. Probl. Eng. 2023(1), 5564509 (2023).

Farooq, A., Khan, M. I. & Ma, W. X. Exact solutions for the improved mKdv equation with conformable derivative by using the Jacobi elliptic function expansion method. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(4), 542 (2024).

Ahmad, J. & Rani, S. Study of soliton solutions with different wave formations to model of nonlinear Schrödinger equation with mixed derivative and applications. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 55(13), 1195 (2023).

Mannaf, M. A., Islam, M. E., Bashar, H., Basak, U. S. & Akbar, M. A. Dynamic behavior of optical self-control soliton in a liquid crystal model. Results in Physics 57, 107324 (2024).

Rehman, S. U., Ahmad, J. & Muhammad, T. Dynamics of novel exact soliton solutions to Stochastic Chiral Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation. Alexandria Engineering Journal 79, 568–580 (2023).

Ananna, S. N., An, T., Asaduzzaman, M. & Rana, M. S. Sine-Gordon expansion method to construct the solitary wave solutions of a family of 3D fractional WBBM equations. Results in Physics 40, 105845 (2022).

Bashar, M. & Islam, S. M. R. Exact solutions to the (2+ 1)-dimensional Heisenberg ferromagnetic spin chain equation by using modified simple equation and improve F-expansion methods. Phys. Open 5(2020), 100027 (2020).

Bashar, M. H., Mawa, H. Z., Biswas, A., Rahman, M., Roshid, M. M., & Islam, J. The modified extended tanh technique ruled to exploration of soliton solutions and fractional effects to the time fractional couple Drinfel’d-Sokolov-Wilson equation. Heliyon. 9(5) e15662 (2023).

Bashar, M. H. & Roshid, M. Exact travelling wave solutions of the nonlinear evolution equations by improved F-expansion in mathematical physics. Communications in Advanced Mathematical Sciences 3(3), 115–123 (2020).

Arafat, S. Y. & Islam, S. R. Bifurcation analysis and soliton structures of the truncated M-fractional Kuralay-II equation with two analytical techniques. Alexandria Engineering Journal 105, 70–87 (2024).

Islam, S. R. & Basak, U. S. On traveling wave solutions with bifurcation analysis for the nonlinear potential Kadomtsev-Petviashvili and Calogero-Degasperis equations. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 8, 100561 (2023).

Islam, S. R., Islam, M. E., Akbar, M. A., & Kumar, D. The stretch coordinate effect, bifurcation, and stability analysis of the nonlinear Hamiltonian amplitude equation. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 13 101126 (2025).

Arafat, S. M., Saklayen, M. A., & Islam, S. M. Analyzing diverse soliton wave profiles and bifurcation analysis of the (3+ 1)-dimensional mKdV-ZK model via two analytical schemes. AIP Advances, 15(1) (2025).

Islam, S. R., Arafat, S. Y., Alotaibi, H. & Inc, M. Some optical soliton solutions with bifurcation analysis of the paraxial nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(3), 379 (2024).

Islam, S. R., Khan, K. & Akbar, M. A. Optical soliton solutions, bifurcation, and stability analysis of the Chen-Lee-Liu model. Results in Physics 51, 106620 (2023).

Yiasir, A. S., Asif, M., Rayhanul, I. S., Saklayen, M. A. & Rahman, M. M. Investigating travelling wave solutions of the (2+ 1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation through the two analytical techniques. Physica Scripta 100(1), 015285 (2024).

Islam, S. R. et al. Stability analysis, phase plane analysis, and isolated soliton solution to the LGH equation in mathematical physics. Open Physics 21(1), 20230104 (2023).

Islam, S. R. Bifurcation analysis and soliton solutions to the doubly dispersive equation in elastic inhomogeneous Murnaghan’s rod. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 11428 (2024).

Rayhanul Islam, S. M., Yiasir Arafat, S. M. & Inc, M. Exploring novel optical soliton solutions for the stochastic chiral nonlinear Schrödinger equation: Stability analysis and impact of parameters. Journal of Nonlinear Optical Physics & Materials 34(05), 2450009 (2025).

Islam, S. R. Bifurcation analysis and exact wave solutions of the nano-ionic currents equation: Via two analytical techniques. Results in Physics 58, 107536 (2024).

He, J. H. & Latifizadeh, H. A general numerical algorithm for nonlinear differential equations by the variational iteration method. Int. J. Numer. Methods. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 30(11), 4797–4810 (2020).

Han, P. F. & Bao, T. Bäcklund transformation and some different types of N-soliton solutions to the (3+ 1)-dimensional generalized nonlinear evolution equation for the shallow-water waves. Math. Methods. Appl. Sci. 44(14), 11307–11323 (2021).

Bashar, M. H., Mannaf, M. A., Rahman, M. M. & Khatun, M. T. Optical soliton solutions of the M-fractional paraxial wave equation. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1416 (2025).

AlQahtani, S. A., Alngar, M. E., Shohib, R., & Alawwad, A. M. Enhancing the performance and efficiency of optical communications through soliton solutions in birefringent fibers. J. Opt. 1-11 (2024).

Younas, U., Sulaiman, T. A. & Ren, J. On the study of optical soliton solutions to the three-component coupled nonlinear Schrödinger equation: applications in fiber optics. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 55(1), 72 (2023).

Inchauspe, A. Á. Solitons: A Cutting-Edge scientific proposal explaining the mechanisms of acupuntural action. Chinese Medicine 9(01), 7 (2018).

Christiansen, P. L., & Scott, A. C. (Eds.). Davydov’s soliton revisited: self-trapping of vibrational energy in protein (Vol. 243). Springer Science & Business Media (2013).

Wazwaz, A. M. Two new Painlevé-integrable extended Sakovich equations with (2+ 1) and (3+ 1) dimensions. Int. J. Numer. Methods. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 30(3), 1379–1387 (2020).

Kumar, S., Rani, S. & Mann, N. Diverse analytical wave solutions and dynamical behaviors of the new (2+ 1)-dimensional Sakovich equation emerging in fluid dynamics. The European Physical Journal Plus 137(11), 1226 (2022).

Cinar, M., Secer, A., Ozisik, M. & Bayram, M. Derivation of optical solitons of dimensionless Fokas-Lenells equation with perturbation term using Sardar sub-equation method. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 54(7), 402 (2022).

Faisal, K. et al. Pure-cubic optical solitons to the Schrödinger equation with three forms of nonlinearities by Sardar subequation method. Results in Physics 48, 106412 (2023).

Rehman, H. U., Yasin, S. & Iqbal, I. Optical soliton for (2+ 1)-dimensional coupled integrable NLSE using Sardar-subequation method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 38(10), 2450044 (2024).

Nofal, T. A. Simple equation method for nonlinear partial differential equations and its applications. Journal of the Egyptian Mathematical Society 24(2), 204–209 (2016).

Cinar, M., Secer, A., Ozisik, M. & Bayram, M. Derivation of optical solitons of dimensionless Fokas-Lenells equation with perturbation term using Sardar sub-equation method. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 54(7), 402 (2022).

Murad, M. A. S., Ismael, H. F. & Sulaiman, T. A. Various exact solutions to the time-fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation via the new modified Sardar sub-equation method. Physica Scripta 99(8), 085252 (2024).

Kayum, M. A., Barman, H. K., & Akbar, M. A. Exact soliton solutions to the nano-bioscience and biophysics equations through the modified simple equation method. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Mathematics and Computing: ICMC 2020, Springer Singapore (pp. 469-482) (2021).

Sakovich, S. A new Painlevé-integrable equation possessing KdV-type solitons. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.01324 (2019).

Wazwaz, A. M. A new (3+ 1)-dimensional Painlevé-integrable Sakovich equation: multiple soliton solutions. Int. J. Numer. Methods. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 31(9), 3030–3035 (2021).

Ma, Y. L., Wazwaz, A. M. & Li, B. Q. A new (3+ 1)-dimensional Sakovich equation in nonlinear wave motion: Painlevé integrability, multiple solitons and soliton molecules. Qual. Theory. Dyn. Syst. 21(4), 158 (2022).

Cinar, M., Secer, A., Ozisik, M. & Bayram, M. Derivation of optical solitons of dimensionless Fokas-Lenells equation with perturbation term using Sardar sub-equation method. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 54(7), 402 (2022).

Rehman, H. U., Akber, R., Wazwaz, A. M., Alshehri, H. M. & Osman, M. S. Analysis of Brownian motion in stochastic Schrödinger wave equation using Sardar sub-equation method. Optik 289, 171305 (2023).

Nofal, T. A. Simple equation method for nonlinear partial differential equations and its applications. Journal of the Egyptian Mathematical Society 24(2), 204–209 (2016).

Ahmad, J. Dynamics of optical and other soliton solutions in fiber Bragg gratings with Kerr law and stability analysis. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48(1), 803–819 (2023).

Ali, K. K., AlQahtani, S. A., Mehanna, M. S., & Wazwaz, A. M. Novel soliton solutions for the (3+ 1)-dimensional Sakovich equation using different analytical methods. Journal of Mathematics, 2023 (2023).

Younis, M., Seadawy, A. R., Baber, M. Z., Yasin, M. W., Rizvi, S. T., & Iqbal, M. S. Abundant solitary wave structures of the higher dimensional Sakovich dynamical model. Math. Methods. Appl. Sci. (2021).

Zhang, T. & Li, J. Exact solitons, periodic peakons and compactons in an optical soliton model. Nonlinear Dyn. 91, 1371–1381 (2018).

Manukure, S. & Booker, T. A short overview of solitons and applications. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 4, 100140 (2021).

Zhu, Y., Huang, C., Li, J. & Zhang, R. Lump solitions, fractal soliton solutions, superposed periodic wave solutions and bright-dark soliton solutions of the generalized (3+ 1)-dimensional KP equation via BNNM. Nonlinear Dynamics 112(19), 17345–17361 (2024).

Wang, K. J., Li, S., Shi, F. & Xu, P. Novel soliton molecules, periodic wave and other diverse wave solutions to the new (2+ 1)-dimensional shallow water wave equation. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 63(2), 53 (2024).

Alam, B. E. & Javid, A. Optical dark, singular and bright soliton solutions with dual-mode fourth-order nonlinear Schrödinger equation involving different nonlinearities. Alexandria Engineering Journal 87, 329–339 (2024).

Wang, K. J. & Li, S. Complexiton, complex multiple kink soliton and the rational wave solutions to the generalized (3+ 1)-dimensional kadomtsev-petviashvili equation. Physica Scripta 99(7), 075214 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Mustafa, Z. & Habib, J. Analyzing dispersive optical solitons in nonlinear models using an analytical technique and its applications. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(1), 77 (2024).

Anco, S. C. & Gandarias, M. L. Nonlinearly dispersive KP equations with new compacton solutions. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications 75, 103964 (2024).

Singh, P. & Senthilnathan, K. Evolution of a solitary wave: optical soliton, soliton molecule and soliton crystal. Discover Applied Sciences 6(9), 464 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Mustafa, Z. & Habib, J. Analyzing dispersive optical solitons in nonlinear models using an analytical technique and its applications. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 56(1), 77 (2024).

Che, W. J., Liu, C. & Akhmediev, N. Fundamental and second-order dark soliton solutions of two-and three-component Manakov equations in the defocusing regime. Physical Review E 107(5), 054206 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Recent advances and challenges on dark solitons in fiber lasers. Optics & Laser Technology, 152, 108116 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jamshad Ahmad: Resources and Supervision. Maham Hameed: Methodology and Writing - original draft. Zulaikha Mustafa: Writing - review and editing, and Investigation. Farah Pervaiz: Conceptualization and Software. Muhammad Nadeem: Visualization and Validation. Yahya Alsayaad: Formal analysis and Funding Project. This paper has been read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, J., Hameed, M., Mustafa, Z. et al. A study of traveling wave solutions and modulation instability in the (3+1)-dimensional Sakovich equation employing advanced analytical techniques. Sci Rep 15, 23332 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00503-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00503-7