Abstract

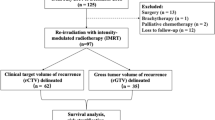

Advancements in surgical and radiotherapy techniques have enhanced locoregional control (LRC) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), yet 30–40% of patients still experience recurrence within 2–3 years. Salvage surgery can result in significant morbidity and often fails to achieve optimal LRC as a standalone treatment. Modern radiotherapy (RT) techniques support highly conformal re-irradiation for small local recurrences with acceptable toxicity. The role of positron emission tomography (PET-CT) based contouring is under evaluation for re-irradiation settings. This retrospective study included patients treated with re-irradiation at a tertiary care center, focusing on those with prior HNSCC in the oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx, who had received radical or adjuvant RT and presented with biopsy-confirmed recurrences or second primary tumors. PET-CT was used for metastatic workup, with rigid image registration on planning CT scan employing a significant 40% SUVmax cut-off for tumor delineation. From January 2019 to June 2022, 85 patients underwent re-irradiation, with a median RT dose of 60 Gy (range: 44–66 Gy); 32 patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT). Treatment planning used the volumetric modulated arc technique (VMAT), with the median Dmax for critical structures ranging from 7 Gy to 63 Gy. Acute grade 3 or higher mucositis, dysphagia, and odynophagia were observed in up to 23.5% of cases. At a median follow-up of 23 months, the 2-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 55.2% and 63.5%, respectively. These promising results support PET-CT contouring-based planning as a potential standard of care in re-irradiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) accounts for approximately 0.9 million cases and results in around 0.4 million deaths annually. Despite advanced radiotherapy and chemotherapy, local recurrence and second primaries in previously irradiated areas remain significant challenges1. Randomized trials show a locoregional recurrence rate of 16–25% in high-risk postoperative HNSCC patients receiving adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT)2. Up to half of those treated with definitive CRT for locally advanced HNSCC experience recurrence, and up to 40% of long-term survivors develop a second primary, with 15% occurring within five years post-treatment3.

Traditionally, salvage surgery has been the preferred option for recurrence, but it often involves extensive resection and risks of post-radiotherapy complications. It is effective in select cases with small recurrences, particularly in the tongue and buccal mucosa. Alternatives include palliative chemotherapy and re-irradiation (RERT). For localized recurrences with poor prognostic factors, re-recurrence rates are high without adjuvant RERT. When surgery is not feasible, definitive RERT with concurrent chemotherapy remains viable, showing good locoregional control with manageable toxicity.

Critical to RERT is managing doses to organs at risk (OARs) like the spinal cord and carotids. Traditional imaging methods like CECT or MRI often fail to distinguish recurrence from post-RT changes, particularly in post-RT and postoperative settings. Modern techniques such as 18-FDG PET-CT provide better sensitivity and specificity in demarcating recurrences4, aiding in reducing gross tumor volume (GTV) and clinical tumor volume (CTV), thereby minimizing toxicity5. PET-CT for radiotherapy planning has been applied in initial diagnoses6, but its role in recurrent settings is still under investigation.

Delivering optimal doses while sparing OARs is challenging. Advanced methods like intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) mitigate RERT-related morbidities. IMRT, as shown by Vargo et al., is viable for large volume disease7, with multi-institutional series demonstrating its dosimetric and clinical benefits8,9,10,11.

In our study, PET-CT was used for contouring patients, and radiotherapy was delivered using VMAT to evaluate progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and report acute and delayed toxicities.

Materials and methods

The study is a retrospective analysis of recurrent HNSCC cases treated at a tertiary care center between January 2019 and June 2022, with approval from the institutional ethics committee (IEC no:11000552). The study adhered to ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and institutional ethics committee protocols. Since the patients were treated with standard institutional protocol and there was no direct contact between the researcher and the patients for the purpose of this study, the need of informed consent was waived. The data has been extracted from the electronic medical records of the institute. It included patients with HNSCC of the oral cavity, oropharynx, or larynx who were treated with curative radiation and presented with biopsy-proven recurrence or a second primary tumor in the head and neck region. Patients were eligible if they were between 18 and 80 years old, had a KPS ≥ 80, at least a 1-year gap from previous radiation, and were suitable for a dose of > 50 Gy in both radical and adjuvant settings.

In line with institutional policy, patients were required to have PET-CT-confirmed nonmetastatic disease to be considered for RERT. PET-CT was used exclusively for local tumor mapping and to rule out metastatic disease, not taken in the treatment position with immobilization setup. For oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx tumors at recurrence, definitive chemoradiotherapy was administered. Oral cavity tumors received surgery followed by adjuvant RT or CRT. Adjuvant CRT was provided in cases of T3-4 tumors, or where the margins were close/positive, or nodes showed positivity with or without extranodal extension. Concurrent chemotherapy included weekly injection of cisplatin at 35 mg/m^2, with carboplatin (AUC-2) used for patients who were ineligible for cisplatin. Patients with lymphovascular space extension (LVE), perineural invasion (PNI), or tumors with a depth of invasion > 5 mm received adjuvant radiotherapy alone. Excluded from the analysis were patients with metastatic disease, extensive local recurrence unsuitable for radical intent CRT, a history of prolonged > grade 3 acute reactions during the first RT, and those who received < 50 Gy in the RERT setting. Patients dependent on gastrostomy tube or ryle’s tube with or without functional larynx were included and these factors were taken into consideration for Recursive Partitioning Analysis (RPA) classification of the patients.

Following dental prophylaxis, patients underwent RT planning, including a contrast-enhanced CT scan in the treatment position with laser alignment to the markers. Head and neck CT scans, with 2.5–3 mm slices, were taken using a helical CT scanner up to the carina level after intravenous contrast injection. CT images were transferred as DICOM files to the contouring workstation, Eclipse planning system. The OARs were contoured per Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) contouring guidelines. For definitive RERT, gross tumor volume (GTV) was mapped based on clinical findings, radiological imaging, and direct/indirect laryngoscopy findings, with PET CT assisting in GTV delineation. The PET CT, initially used for disease diagnosis, guided target delineation (Fig. 1). The DICOM files underwent rigid registration with CTsim as the target image and CTpet as the source image, initially auto-matched and manually refined. Using the PET adaptive threshold technique, the SUVmax of the tumor is set for contouring purpose. Now the PET components were overlaid on CTsim to define disease, using a 40% SUVmax threshold algorithm for GTV delineation, followed by slice-by-slice validation to include suspicious, contrast-enhancing regions. A 5 mm planning target volume (PTV) margin was standardly added to the GTV in re-irradiation.

For adjuvant RERT, the preoperative PET CT was similarly fused with CTsim, involving the same matching procedure (Fig. 2). The auto-contoured GTV volume was compared to the post-operative bed (CTV) contour on CTsim to ensure inclusion of suspicious volumes, subsequently receiving a 5 mm PTV margin.

The prescribed dose was 66 Gy/33 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction over 6.5 weeks for definitive CTRT, and 60 Gy/30 fractions at 2 Gy per fraction over 6 weeks for the adjuvant setting, observing OAR limits. Dosimetric constraints were met without significant PTV compromise, as detailed in Table 1. Planning was conducted using VMAT with single or double arc depending on plan complexity and critical OAR proximity. RT delivery utilized a Varian TrueBeam system (Palo Alto, California) with a 5 mm MLC width at the isocenter. Treatment verification involved online cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) for every alternate fraction.

During treatment, patients were assessed weekly in the outpatient department (OPD), with acute toxicities graded per RTOG acute toxicity criteria. Follow-up protocols post-radiotherapy complied with institutional policy: monthly visits for the initial 3 months, bi-monthly for the next 6 months, and quarterly thereafter. Late toxicities were assessed as per RTOG late morbidity criteria12, and trismus grading according to criteria by Dijkstra et al.13. In radical RERT with chemotherapy, response assessment was conducted 3 months after radiotherapy completion using PET-CT. Adjuvant RERT follow-up involved clinical examination and imaging for suspected locoregional or distant failure, with biopsy for suspected lesions deemed necessary for disease-free survival (DFS) evaluation if deemed positive. To assess outcomes based on RPA class as proposed by the MIRI collaborative group, patients were categorized into class I, II, and III8.

Patients with a disease-free interval (DFI) of more than two years between the previous RT and current histopathologically confirmed recurrence and who underwent resection were categorized as class (I) Patients with a DFI greater than two years but who were unresected, or a DFI of less than two years without organ dysfunction, were considered class (II) Those with a DFI of less than two years and with organ dysfunction were categorized as class III.

This classification helped in stratifying patients for outcome analysis, potentially guiding treatment decisions and predicting prognosis based on the RPA class they belonged to, thus customizing therapeutic approaches more effectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis utilized SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM). OS was calculated from biopsy-confirmed recurrence to death from any cause, DFS from reirradiation initiation to disease progression or death, and DMFS from RERT initiation to distant progression or death. Survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with log-rank tests comparing outcomes. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 85 patients received reirradiation during the study period. Out of these, 4 patients had a second primary tumor within the previously irradiated area, and the rest were recurrences. The baseline patient and disease characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The most common site was the buccal mucosa (70.5%), followed by the tongue (16.4%). All patients were treated with VMAT. The median PTV volume was 207 cc (ranging from 21 to 786 cc). The dosimetric constraints and median parameters achieved are shown in Table 1. Twelve patients were lost to follow-up, and in conservative assessments, all of them were censored for DFS and OS events.

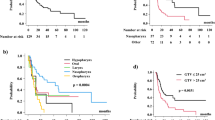

Efficacy outcomes

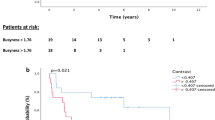

At a median follow-up of 23 months (ranging from 4 to 54 months), the 2-year DFS rate was 55.2% ±7.1% (95% CI) (Fig. 3), while the 2-year OS rate was 63.5% ±7.6% (95% CI) (Fig. 4). Further analysis based on RPA class showed median 2-year OS with 95% CI rates of 74.5% ±9.4%, 45.6% ±14%, and 50% ±23.8% for classes I, II, and III, respectively, with a p-value of 0.09 (Fig. 5). Combined, the OS for RPA class I was significantly better than for classes II and III (p = 0.045). When comparing adjuvant RERT to definitive RERT, the 2-year OS was better in the resected subgroup [68.8% ±8% (95% CI) vs. 53.9% ±14.3%(95% CI)], but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.15). Similarly, there was no significant difference in median DFS between adjuvant and radical RERT patients (36 months vs. 31 months, p = 0.72).

Pattern of failure

At the time of analysis, 27 patients had biopsy and/or radiologically confirmed recurrences after RERT. Of these, 18 were in the adjuvant RERT subgroup, and 9 in the radical RERT group. Additionally, 2 patients in each group developed a second malignancy in the head and neck region. In the adjuvant RERT group, local, locoregional, and distant recurrences were observed in 11, 5, and 2 patients, respectively. Among the local recurrences, the most common site was at the upper margin of the post-operative region adjoining the low infratemporal region (6/11 patients). For tumors in anatomically complex and functionally critical regions like the oral cavity, the use of only PET-based imaging might lead to underestimation of the required margins. This discrepancy underscores the importance of tailoring margin settings based on tumor type, location, and imaging findings, with a focus on including adjacent anatomical structures at risk of subclinical disease involvement. In the radical RERT group, local and locoregional recurrences were established in 5 and 2 patients, with no distant metastasis. Among these, 2 out of 5 patients experienced recurrence within 1 cm of the reirradiation region.

Toxicity

Acute

Acute grade 3 or higher mucositis, dysphagia, and odynophagia were observed in 14.1%, 21.1%, and 23.5% of cases, respectively. Only 5 out of 85 patients required treatment interruption due to grade 3 odynophagia. Nasogastric tube insertion was necessary for 37 out of 85 patients. Treatment compliance was generally good; however, one patient in the adjuvant CRT group, with a planned dose of 60 Gy, required RT stoppage at 50 Gy due to grade 4 mucositis. Two other patients in the radical CRT group, planned for 66 Gy, were stopped at 60 Gy due to persistent grade 3 odynophagia and mucositis lasting more than 7 days.

Late

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) was observed in 3 patients (median duration from RT was 5 months), with 2 developing palatal necrosis and 3 experiencing orocutaneous fistulas, managed conservatively. Of these 8 patients, 6 were from the adjuvant RERT group. The median cumulative mandibular dose (physical summation of Dmax from both RT plans) in patients developing ORN was 120 Gy (ranging from 118 to 122 Gy). The median gap between initial RT and RERT was 1.6 years (ranging from 1 to 2.8 years). No patient reported late spinal cord toxicity. Late toxicity manifested as Grade 2 or higher subcutaneous tissue toxicity in 49% of patients, with no cases of subcutaneous necrosis. However, 8.2% had grade 3 subcutaneous tissue toxicity, all in the adjuvant RT group. Moderate (grade 2) xerostomia was present in 52 out of 85 patients even before RERT, possibly due to prior RT. Post RERT, grade 3 xerostomia was observed in 22 patients.

Trismus of grade 2 or higher was observed in 56 out of 85 patients. It was more prevalent in postoperative patients compared to those receiving radical CTRT. This condition likely resulted from the treatment’s effects on the masticatory muscles or associated tissues in the irradiated area, impacting patients’ quality of life (QOL) by limiting mouth opening and potentially affecting nutrition and oral hygiene.

The comprehensive analysis of patient characteristics, treatment efficacy, patterns of failure, and acute and late toxicities provides crucial insights into the management of recurrent HNSCC, tailoring reirradiation strategies to optimize outcomes while minimizing adverse effects. Continued follow-up and further studies will be essential to refine these approaches and improve long-term patient care.

Discussion

Three pivotal trials—RTOG 9610, RTOG 9911, and French Groupe d’étude—have demonstrated re-irradiation’s value in treating local recurrences or second primary HNSCC tumors and significantly influence current practices14,15,16. Typically, salvage surgery serves small-volume recurrences, with Institut Gustave Roussy’s Phase II study showing that concurrent chemoradiotherapy post-surgery can enhance locoregional control (LRC)17. Janot et al. corroborated this with improved disease-free survival (DFS) through adjuvant RERT post-surgery, even though it didn’t enhance overall survival (OS)16. In our study, 68.2% of patients received adjuvant RT, which benefited resected patients over those treated radically, albeit not to a statistically significant degree.

Patient selection for RERT is challenging. RTOG 9911 and 9610 set prerequisites like a one-year gap since prior RT, unsuitability for surgery, and specific health parameters (ECOG 0–1 or KPS > 60%)2,18. Janot et al. focused on cases with significant infiltration or nodal recurrence, excluding those with serious post-RT complications16. Their selection approach was directed by findings highlighting factors like time between therapies, salvage surgery, and organ function impact on re-irradiation outcomes, aligning our patient group toward a favorable RPA classification8,9,19.

Fractionation, RT techniques, and chemotherapy regimens were critically assessed in RTOG studies. Like the MIRI collaborative findings reporting 80.1% success with once-daily fractions, we opted for this dosing due to proven advantages and practical considerations. The development of IMRT has shown promising results, as seen in a study by Lee et al. where IMRT significantly reduced locoregional failure compared to conventional RT20. Kharofa et al. found IMRT superior in minimizing late toxicities compared to 3D-CRT21, encouraging our full adoption of VMAT, a refined IMRT form.

SBRT presents precise radiation delivery, offering potential benefits for re-irradiation, as indicated by studies reporting promising survival outcomes and reduced late toxicity22,23,24. However, a comparison by Vargo et al. highlighted a better toxicity profile but poorer OS for SBRT compared to IMRT7. Based on tumor volume assessments and prior research, we used conventional fractionation and VMAT for treatment.

Controversy persists around RT doses and re-irradiation volumes. Caudell et al.‘s analysis emphasized doses ≥ 66 Gy in radical contexts for optimal results9. Table 3 summarises all the studies which utilised reirradiation in HNSCC. Our study maintained GTV and CTV to primary sites without elective nodal irradiation, using reduced margins justified by PET-CT contouring accuracy5,25. This technique provided effective volume optimization, resulting in fewer acute and late complications, notably lower rates of Grade 3 subcutaneous fibrosis and osteoradionecrosis than other studies report26. The ALARA principle aided in effectively controlling doses to critical OARs, as seen in our lower morbidity rates.

In our study cohort, there was a trend towards improvement in OS in adjuvant RERT group vis a vis definitive RERT group, but it failed to meet statistical significance level (p = 0.15) and thus warrants cautious interpretation. This might be attributed to smaller sample size and potentially a larger cohort of each group might have shed more insight into it. Adjuvant RERT is mostly limited to relatively earlier stage tumors, mostly limited to oral cavity region. Definitive RERT on the other hand is mostly used in oropharynx, hypopharynx and larynx subsites. Given the closer proximity of pharyngeal and laryngeal tumor to spinal cord and carotids making the planning more challenging and need of higher BED in definitive RERT coupled with need of concurrent chemotherapy, the outcomes are expected differently. There is an inherent patient selection and more intense treatment bias inbuilt into this subgroup analysis, and these factors need to be considered while interpreting this result.

The choice of imaging for tumor delineation on RERT setting remains critical in optimising RERT outcomes. Contouring of GTV and CTV for atypical tumor location like retromolar trigone or parapharyngeal space tumors with extensive perineural spread to infratemporal region remain challenging. PET imaging is a valuable tool for defining target volumes, its limitations in accurately delineating microscopic tumor extension should be carefully considered. PET-CT alone underestimates these atypical radiological finding and also at time fails to detect recurrence from post treatment non tumorous changes. The role of complementary diagnostic modalities, such as clinical palpation and MRI, is crucial in ensuring comprehensive coverage of potential tumor spread. Over the time the introduction of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and T1 contrast dynamic perfusion imaging (DCE-MRI) which are known as functional MRI, has evolved as alternative imaging technique in characterising tumor recurrence in HNC. Both DWI, and post-contrast DCE-MRI have better potential in detecting as well as differentiating tumour recurrence from post-therapy non-tumorous changes which are very important for accurate delineation in RERT patients27. However, in case of recurrent disease with cervical node as the primary recurrent site the utility of diffusion weighted MRI lack adequate sensitivity and specificity28. This has been attributed to reactive nodal changes with multiple germinal centres and stromal fibrosis which results in microstructural barriers within lymph node, thus reducing apparent diffusion coefficient. Therefore, a more nuanced, multimodal approach that integrates PET-CT, functional MRI, and clinical examination is warranted for CTV margin definition, especially in cases of oral cancer and this multimodal approach for contouring can be looked into for future studies. Several studies have evaluated the role of PET-CT, functional MRI, and other imaging modalities, both pre- and post-treatment, in combination with clinicopathological factors as part of radiomics approaches to predict overall survival in HNC. However, there is a notable paucity of radiomics-based data in the context of re-irradiation, highlighting a critical gap and paving the way for future research in this area29,30.

On analyzing the pattern of recurrence in our patient cohort, a few cases demonstrated failure near the upper margin of the postoperative region. This may be attributed to the underestimation of CTV expansion in areas of PNI extending toward the infratemporal region, which might have been missed on preoperative PET-CT imaging. Incorporating functional MRI and careful delineation of the infratemporal region may help optimize CTV volumes. Additionally, marginal recurrences may arise due to changes in CT anatomy during radiotherapy, influenced by postoperative edema and seroma evolution. Close monitoring with daily CBCT and judicious application of adaptive radiotherapy could potentially mitigate the risk of such marginal failures.

Our retrospective analysis, despite inherent limitations such as smaller sample size and challenges with PET/CT acquisition, is pioneering in evaluating PET-CT-based contouring’s impact on RERT. We accept that including larger number of patients of only one subgroup that is either definitive RERT or only adjuvant RERT could have allowed more generalizability of our data.

The large number of buccal mucosa patients in our study can be attributed to the high prevalence of buccal mucosa tumors in India and especially in our region as well as the rampant use of oral chewable tobacco. In view of noted acute and late sequelae, it would have been useful to assess QOL for patients undergoing RERT. This would have helped correlate effect of these sequelae on the QOL of the patients and perhaps even correlation between QOL and survival. This was not done as study is retrospective and we will consider this for future prospective studies. Therefore, large prospective study with possible incorporation of QOL data at various time points and organ function outcomes could establish this PET-CT based approach as a standard, potentially improving recurrent HNSCC outcomes. Limited follow up period for some patients is another limitation of our study which can influence the reported outcomes. Given the high number of censored cases in the Kaplan-Meier analysis a formal sensitivity analysis would have been useful. However, it was not feasible due to smaller sample size, and it remains a limitation of our study. A registry-based prospective follow-up with extended follow up duration is required to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the efficacy of PET based contouring and its impact on patient outcomes in future research.

Conclusion

PET-CT-based contouring for RERT offers encouraging clinical results and should be considered alongside CT/MRI-based contouring. Careful patient selection and advanced imaging and radiotherapy techniques could significantly improve outcomes in recurrent HNSCC, addressing historically challenging prognoses.

Data availability

The deidentified data can be made available to the readers by contacting the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Global Cancer Observatory. International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. Accessed on January 23, (2023). Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/

Cooper, J. S. et al. Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/intergroup phase III trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 84, 1198–1205 (2012).

Brockstein, B. et al. Patterns of failure, prognostic factors and survival in locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy: a 9-year, 337-patient, multi-institutional experience. Ann. Oncol. 15, 1179–1186 (2004).

Gupta, T. et al. Diagnostic performance of post-treatment FDG PET or FDG PET/CT imaging in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 38 (11), 2083–2095 (2011).

Wang, K. et al. Target delineation in stereotactic body radiation therapy for recurrent head and neck cancer: a retrospective analysis of the impact of margins and automated PET-CT segmentation. Radiother. Oncol. 106 (1), 90–95 (2013).

Grégoire, V. & Chiti, A. Molecular imaging in radiotherapy planning for head and neck tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 52 (3), 331–334 (2011).

Vargo, J. A. et al. A multi-institutional comparison of SBRT and IMRT for definitive reirradiation of recurrent or second primary head and neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 100, 595–605 (2018).

Ward, M. C. et al. Refining patient selection for reirradiation of head and neck squamous carcinoma in the IMRT era: A multi-institution cohort study by the MIRI collaborative. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 100, 586–594 (2018).

Caudell, J. J. et al. Volume, dose, and fractionation considerations for IMRT-based reirradiation in head and neck cancer: A multi-institution analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 100, 606–617 (2018).

Bush, K., Townson, R. & Zavgorodni, S. Monte Carlo simulation of RapidArc radiotherapy delivery. Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 359–370 (2008).

Tsai, C. L., Wu, J. K., Chao, H. L., Tsai, Y. C. & Cheng, J. C. Treatment and dosimetric advantages between VMAT, IMRT, and helical tomotherapy in prostate cancer. Med. Dosim. 36 (3), 264–271 (2011).

Cox, J. D., Stetz, J. & Pajak, T. F. Toxicity criteria of the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) and the European organization for research and treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 31 (5), 1341–1346 (1995).

Dijkstra, P. U., Huisman, P. M. & Roodenburg, J. L. Criteria for trismus in head and neck oncology. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 35 (4), 337–342 (2006).

Spencer, S. A. et al. Final report of RTOG 9610, a multi-institutional trial of reirradiation and chemotherapy for unresectable recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 30, 281–288 (2008).

Langer, C. J. et al. Phase II study of low-dose Paclitaxel and cisplatin in combination with split-course concomitant twice-daily reirradiation in recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of radiation therapy oncology group protocol 9911. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 4800–4805 (2007).

Janot, F. et al. Randomized trial of postoperative reirradiation combined with chemotherapy after salvage surgery compared with salvage surgery alone in head and neck carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 5518–5523 (2008).

De Crevoisier, R. et al. Full dose reirradiation combined with chemotherapy after salvage surgery in head and neck carcinoma. Cancer 91::20712001–20712076

Bernier, J. et al. Defining risk levels in locally advanced head and neck cancers: a comparative analysis of concurrent postoperative radiation plus chemotherapy trials of the EORTC (#22931) and RTOG (# 9501). Head Neck. 27 (10), 843–850 (2005).

Margalit, D. N. et al. Patient-oriented toxicity endpoints after head and neck reirradiation with intensity modulated radiation therapy. Oral Oncol. 73, 160–165 (2017).

Lee, N. et al. Salvage re-irradiation for recurrent head and neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 68, 731–740 (2007).

Kharofa, J. et al. Continuous-course reirradiation with concurrent carboplatin and Paclitaxel for locally recurrent, nonmetastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head-and-neck. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 83, 690–695 (2012).

Heron, D. E. et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of a phase I dose-escalation trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 75, 1493–1500 (2009).

Diao, K. et al. Stereotactic body ablative radiotherapy for reirradiation of small volume head and neck cancers is associated with prolonged survival: large, single-institution, modern cohort study. Head Neck. 43 (11), 3331–3344 (2021).

Rudzianskas, V. et al. Reirradiation of recurrent head and neck cancer using high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 32 (5), 297–303 (2012).

Skjøtskift, T. et al. Dose painting for re-irradiation of head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol. 57 (12), 1693–1699 (2018).

Das, S., Patro, K. C. & Mukherji, A. Recovery and tolerance of the organs at risk during re-irradiation. J. Curr. Oncol. 1, 23–28 (2018).

El Beltagi, A. H. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of head and neck cancer: performance and potential. Neuroradiol. J. 32 (1), 36–52 (2019).

Holzapfel, K. et al. Value of diffusion weighted MR imaging in the differentiation between benign and malignant cervical lymph nodes. Eur. J. Radiol. 72, 381–387 (2009).

Liu, Z. et al. Radiomics-based prediction of survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma based on pre- and post-treatment 18F-PET/CT. Aging 12, 14593–14619 (2020).

Bogowicz, M. et al. Perfusion CT radiomics as potential prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 58, 1514–1518 (2019).

Bhalavat, R. et al. High-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy in recurrent head and neck cancer: an effective salvage option. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 10 (5), 425–430 (2018).

Lee, A. et al. Evaluation of proton therapy reirradiation for patients with recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (1), e2250607 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Ms. Ankita Pal, Department of Biostatistics for her help in statistical analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing.ARK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing.AM: Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing.AKC: Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing.AK: Data Collection, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.AJK: Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing.NHP: Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing.AM: Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing.SP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nanda, S.S., Kapoor, A.R., Mukherji, A. et al. Positron emission tomography directed re-irradiation using volumetric modulated arc technique in recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 18721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00557-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00557-7