Abstract

A Conduction cooled superconducting magnet (SM) for human magnetic resonance imaging, made of Nb3Sn superconducting coils, has been designed. The magnet features a warm bore with a diameter of 850 mm and a central field strength of 7 T. The size and positioning of a bundle of seven epoxy-impregnated coils were determined using both linear and nonlinear optimization methods. These methods ensured that the superconducting coils achieved a magnetic field uniformity of 10 ppm within a 400 mm diameter spherical volume (DSV). The magnet was designed to operate at a current of 250 A in a cryogenic system, and its temperature will be maintained below 8 K through conduction cooling provided by a Gifford-McMahon (G-M) cryocooler at its second-stage cooling capacity. The SM and its cryogenic system were designed according to a comprehensive analysis of the mechanical and thermal features of the magnet system. The design was evaluated and validated by Finite Elements simulations. The results confirmed that the magnet is capable of stable and reliable operation at low temperatures, effectively achieving conduction cooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a radiation-free and non-harmful diagnostic tool widely used for detecting diseases in the human body. The clarity of MRI scans is directly influenced by the strength of the magnetic field, stronger fields result in higher imaging resolution1. At present, most commercial MRI systems operate at magnetic flux densities of 1.5 T or 3.0 T2. However, these are generally insufficient for obtaining detailed images of brain and orthopedic structures within a short time frame. High-field superconducting magnets (SM), such as those operating at 7 T, 9.4 T3,4,5 and 11.7 T6,7 provide superior imaging clarity, while are challenging to manufacture. In the future, 7 T magnets will become the standard for full-body human imaging8. To meet these evolving demands, companies such as Siemens and GE have developed superconducting magnets designed for 7 T imaging. These systems use NbTi coils immersed in liquid helium and incorporate cryocoolers to re-condense evaporated helium, which ensure that the temperature of the magnet remains below 4.2 K to stabilize the magnetic flux densities of the magnet above 7 T. Similarly, Bruker’s 7 T animal imaging systems also rely on liquid helium immersion. Given helium’s status as a non-renewable resource, alternative approaches are being explored to improve sustainability. For instance, a 7 T magnet system can utilize conduction-cooled to maintain the operating temperature necessary for the magnet. However, a fully conduction-cooled 7 T magnet system has not been publicly reported.

To achieve the aforementioned objectives, this study presented the design of a superconducting magnet system with active shielding and conduction cooling9 for 7 T human imaging. The superconducting magnet is composed of Nb3Sn10,11, which have a higher critical temperature12,13. This material enables superconducting conditions at elevated temperatures, facilitating conduction cooling without liquid helium. Nb3Sn coils are also smaller and lighter, allowing for a more compact and efficient magnet design. The magnet was placed in a cryogenic system (CS) and conduction cooling was provided using two G-M second-stage cryocoolers. Section 2 detailed the design of the magnet and its mechanical structure, along with a comprehensive analysis of the system’s heat leakage (HL). In Sect. 3, finite element-based simulations were conducted to evaluate the magnetic field strength, field uniformity, circumferential stress of the magnet, the stress distribution within the mechanical structure, and the system’s heat leakage during normal operation. These simulations could verify the reliability of the magnet system in terms of electromagnetic performance, mechanical stability, and cryogenic operation.

Magnet system design

When designing the Nb3Sn magnet system for 7 T body imaging, careful consideration must be given to the distribution of the superconducting magnet coils. This ensures that the magnet achieves an optimal balance among aperture size, magnetic field uniformity, field strength, electromagnetic stress, and cost constraints14,15,16. The magnet’s quench protection system must also be taken into account to prevent damage caused by the loss of superconductivity, which could result in total failure. Additionally, the mechanical strength of the cryogenic system’s structural components must be thoroughly evaluated to ensure the stability of the magnet’s mechanical properties. Furthermore, concerning the magnet’s temperature, as regulated by the G-M second-stage cryocooler, less than the operating temperature of the superconductor (~ 8 K) to ensure that the magnetic flux density is stabilized at 7 T. The design workflow for the magnet system, as proposed in this study, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Magnet design

In order to accurately describe the geometry of the Nb3Sn superconducting windings, the design as displayed in Fig. 2(a), included the diameter of spherical volume (DSV), coil regions, and the 5 Gauss stray field boundary in the solving space, where 1 coil regions were predefined in the figure to minimize both the length of the coils and the budgetary cost. Each coil region was uniformly divided in axial and radial directions to form a two-dimensional (2D) grid, and each grid point was regarded as an ideal energized circular ring. As the superconducting magnets were symmetrically distributed around the z-axis, the magnetic induction intensity could be described using the cylindrical coordinate system (z, r) where z represents the axial direction and r is the radial direction. The radial and axial magnetic field components (Br, Bz) at the i-th target point, with spatial coordinates (Ri, Zi), generated by the j-th rectangular grid at (rj, zj), can be mathematically expressed as:

where k is defined as:

where K(k) and E(k) are elliptic integrals of the first and second kinds, respectively. The equations are described below:

To determine the coil distribution, the design requirements of the Nb₃Sn MRI superconducting magnets, as listed in Table 1, were used as a basis. For the #1 coils within the solving space, a linear optimization method17 was initially employed. This method optimized the coil weight as the objective function while using the magnetic field uniformity and shielding as constraints, resulting in the initial conductor concentration blocks and the current density distribution of the coils. To further refine the conductor distribution and achieve a more compact arrangement, a nonlinear programming (NLP) calculation method18 was applied across the entire current-carrying area. The NLP method optimized the coil’s minimum length and volume as objective functions while imposing constraints, such as the central field, DSV inhomogeneity, 5 Gauss lines, coil relative positions, coil boundaries, conductor load lines, and hoop stresses. The magnet coil was divided into seven coil blocks, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b), by the above mentioned optimization analysis, where the blue rectangular block represents the main coil and the red rectangular block is the shielded coil. The main coils carried forward currents, while the shielding coils carried reverse currents. Both the main and shield coils were fabricated using rectangular cross-section multifilamentary Nb3Sn/Cu superconducting wires with a 50:50 Cu to non-Cu ratio, insulated dimensions of 2.25 mm × 1.55 mm, and the superconductor cross-sectional area of 1.47 mm2. The current-sharing temperature of the conductor was 11.6 K at 8 K and 8.35 T, and the critical current density was 697 A/mm2.

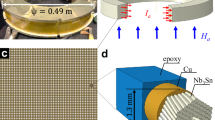

The 7 T MRI superconducting magnet designed in this study adopted the dry winding method. The superconducting wire was first wound onto the stainless-steel skeleton without adhesives or resin, ensuring precise alignment and minimizing strain on the conductor. After being shaped, the coils undergo heat treatment at approximately 700 °C to facilitate the formation of the superconducting phase, ultimately resulting in Nb3Sn superconducting coils. To prevent the softening of the stainless steel skeleton during heat treatment, end plate flanges are welded to the exterior of the stainless steel skeleton. Following heat treatment, the coil is placed in a vacuum environment and impregnated with epoxy resin. This epoxy resin, commonly utilized as an electrical insulation and filler material in superconducting magnets, could mitigate coil expansion caused by the Lorentz force and enhance the mechanical stability between the magnet coil and the skeleton19, and it was also infused with aluminum nitride, which was both an insulator and possesses high thermal conductivity, thereby enhancing the cooling capacity of the coil.

Quench protection is a crucial aspect of the magnet design. For this paper, we present a preliminary design of a quench protection system for a 7 T MRI magnet. The magnet quenching system comprises quench detection and protection circuits. When the voltage taps and temperature sensors embedded within the coils detect a magnetic quench, the heaters in the protection circuits are activated to prompt the superconducting coils to lose their superconducting state in advance. This action ensures that the coils are not over-stressed. Subsequently, the diodes are triggered to shunt the current, allowing the energy to be released through energy dissipation resistors. This process guarantees that the energy is not absorbed by the magnets, thereby preventing a significant temperature rise.The detailed design of the protection circuitry will be finalized in a later stage of the magnet design process. In this study, the field uniformity and magnetic field strength of the magnet are simulated and verified by finite element analysis in Sect. 3.2, and the electromagnetic stress of the magnet is analyzed using finite element simulations in Sect. 3.3.

Mechanical design of cryogenic systems

-

The 7 T MRI SM system consisted of a SM and a conduction-cooled CS, and a schematic diagram of the magnet system is illustrates in Fig. 3. To ensure the stable operation of the SM, the CS must account for both the mechanical and thermal stability of the magnet. The SM was directly connected to the second-stage cold head of RDE-418D4 through a conduction-cooled copper ring, and the temperature was stabilized at 8 K. To achieve minimization of heat leakage caused by the obvious temperature difference between the external environment and the magnet, the system employed vacuum sealing in a room-temperature Dewar and incorporated a thermal radiation shield between the superconducting magnet and the Dewar. The thermal radiation shield was connected to the first-stage cold head of the RDE-418D4 through a cooling mechanism, and the temperature of the thermal radiation shield was stabilized at 60 K. To minimize HL from radiation, the surface of the thermal radiation shield was wrapped with 20 multi-insulated layers consisting of highly reflective aluminum foil. As a residual temperature difference existed between the magnet and the thermal radiation shield, additional measures were required to prevent heat transfer to the coils. A thin layer of stainless steel was therefore applied to the coil skeleton, effectively reducing radiant heat leakage and enhancing the system’s thermal efficiency.

-

The system primarily comprised superconducting magnets, cryocoolers, Dewars, thermal radiation shield, current leads, service towers, suspension structures, cold-conducting copper rings, and other components. To maintain mechanical stability and ensure that the individual containers remain coaxially aligned, the magnet and the thermal radiation shield were connected to a reinforcing ring on the room-temperature Dewar via a suspension structure. This structure was made of carbon fiber composite material (T700)20, with low thermal conductivity and high mechanical strength at low temperatures. In addition, materials with high thermal resistance, e.g., stainless-steel, were used for the Dewar, while materials with high thermal conductivity, such as aluminum alloy, are employed for the thermal radiation shield, ensuring optimal thermal performance of the system.

-

During magnet normal operation, it is essential to consider not only the thickness of the inner and outer cylinders of the room-temperature Dewar to withstand the vacuum pressure, but also the shape and cross-sectional area of the suspension structure to ensure sufficient mechanical strength.This consideration was vital for maintaining the mechanical stability of the system. Consequently, we designed the thermal radiation shield’s suspension structure consisting of an eight cylindrical tie-rod configuration, each with a diameter of 20 mm and a length of 774 mm. For heavier magnets, the suspension structure utilizes eight sets of runway-type rods, each with a cross-sectional area of 160 mm² and a length of 1080 mm. The arrangement of the suspension structure was illustrated in Fig. 3(b). The inner cylinder of the room-temperature Dewar was designed with a wall thickness of 5 mm, and the outer cylinder was constructed with a wall thickness of 10 mm.The solid mechanic simulation and validation of the mechanical structure in the cryogenic system are presented in Sect. 3.3.

Thermal design of cryogenic systems

The key to design a SM system is the ability of the cryogenic system to offer a cryogenic environment stable enough for the SM to remain below the critical temperature. In this section, the thermal design of the CS is described and the HL of the CS is fully analyzed. By optimizing material selection, refining the design of key components, minimizing HL and enhancing thermal conductivity, the system achieves a low-temperature environment with high thermal uniformity. These measures ensure reliable operation of the SM in a conduction-cooled CS.

HL analysis

The heat transfer in the 7 T conduction cooling cryogenic system primarily involves heat conduction and heat radiation. During normal operation of the magnet, the HL in the CS and the cold power of the cryocooler must maintain a dynamic balance. As the system stabilizes, the initial heat leakage is mainly due to the conduction of heat through the thermal radiation shield suspension structure and the magnet suspension structure. The conduction heat leakage follows the Fourier equation:

where ΔT/ΔL is the temperature gradient along the heat flow direction, A[m2] is the cross-sectional area of the suspension structure, and k[W/(m.K] is the thermal conductivity of the material dependent on temperature.

In order to maintain low thermal conductivity and high mechanical strength, the two types of suspension structures attached to the reinforcement ring need sufficient tensile strength, as well as a large thermal resistance, and we constructed the suspension structures at different locations in the system by T700 and stainless-steel materials. In addition, heat sinks were installed on the magnet suspension structures to maintain the thermal uniformity. These heat sinks dissipate higher heat fluxes generated at room temperature, which are then cooled by the first stage of the G-M cryocooler’s cold head, providing a high cooling capacity.

The second source of HL in the system arises from radiant heat transfer. This includes radiant heat leakage from the room-temperature Dewar to the thermal radiation shield, as well as from the thermal radiation shield to the coil skeleton. The magnitude of radiant heat follows the Steffen-Boltzmann law:

As described in the following equations, where TH and TL denote the temperatures among the wrapped Dewar, the skeleton, and the shield, the radiant heat exchange21 can be expressed as:

In Eq. (8), σ represents the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.67 × 10⁻⁸ W/m²/K⁴), while AH and AL correspond to the surface areas aligned along the same axis. The parameters εL and εH refer to the emissivity of the radiating material’s surfaces, and N signifies the number of insulating layers. The emissivity values of 304 stainless-steel and aluminum alloy at low temperatures are 0.07 and 0.10, respectively22.

From the above-formulated equation, it is evident that the radiant heat leakage is proportional to the fourth power of the temperature difference. Thus, the thermal radiation shield effectively mitigates radiant heat exchange between the room-temperature Dewar and the magnet. Additionally, the outer wall of the coil skeleton remarkably decreases the radiant heat leakage from the shield to the coils. Utilizing materials with low surface emissivity further contributes to reducing the radiant heat leakage.

The third source of heat leakage in the system primarily arises from conduction heat leakage and Joule heat leakage through the copper leads and high-temperature superconductor current leads. This study employed an engineering calculation method, where the heat leakage for copper leads is 10 W per 100 A, and for high-temperature superconductor current leads, it is 0.1 W per 150 A. The system utilized two sets of copper leads and high-temperature superconductor current leads. The design of the high-temperature superconductor current leads incorporated a single superconducting tape made of YBCO material, which welded on the two sides of a stainless-steel bracket (SSB) and sealed with Kapton. The ends of the SSB were hollow to minimize HL. In addition, considering that the conduction heat leakage from the copper lead and the Joule heat generated during operation will significantly increase HL to the thermal radiation shield. Based on the design experience in engineering, the length of the copper leads was designed to be 400 mm and the radius was designed to be 2 mm, which minimized the HL to a greater extent.

The conduction-cooled cryogenic system utilized two Sumitomo RDE-418D4 second stage G-M cryocoolers. The cryocoolers had a second-stage cold head of about 5 W at 8 K and a first-stage cold head of about 45 W at 60 K. Assuming that the heat shield temperature was 60 K when the system temperature was fully cooled, the heat shield temperature was 70 K when the magnet was operated at a current of 250 A, and the estimated temperature of the SM was 8 K. All sources of heat leakage were analyzed and evaluated, and the calculated HL of the heat shield and SM are presented in Table 2. The heat transfer simulation verification of the cryogenic system is detailed in Sect. 3.1.

Finite element analysis

Heat transfer simulation

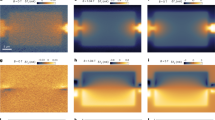

Using the solid heat transfer module of COMSOL finite element analysis software, we performed heat transfer analyses on the structures in the CS. The heat leakage from the high temperature leads was simulated using the COMSOL software by setting temperatures of both ends of the high-temperature superconductor current leads to 60 K and 8 K. The simulation results indicated that the HL for a single current lead was 0.035 W, with the corresponding temperature distribution demonstrated in Fig. 4(a).

Solid-state thermal simulation results. (a) Temperature distribution in the high-temperature superconductor current leads, (b) Temperature distribution in the tie rods supporting the thermal radiation shield, (c) Temperature distribution in the tie rods supporting the magnet, (d) Surface heat flux on the outer wall of the coil skeleton.

The heat leakage of the thermal radiation shield suspension structure and the magnet suspension structure was also simulated. The simulation results indicated that the heat leakage of a single tie rod in the thermal radiation shield suspension structure was 0.17 W, while the heat leakage for a single set of tie rods in the magnet suspension structure was 0.61 W in the normal temperature region and 0.014 W in the cold temperature region. The temperature distributions are illustrated in Figs. 4(b) and 4(c).

In the radiant heat simulation, as the thermal radiation shield was placed on the outside of the 20 multi-insulated layers, the complexity of the simulation was elevated. To simplify the calculation, the analysis concentrated only on the thermal radiation shield and the outer wall of the coil skeleton. For this simulation, the thermal radiation shield temperature was set to 60 K with a surface emissivity of 0.1, while the temperature of the outer wall of the coil skeleton was set to 8 K. The simulation revealed that the heat leakage through the coil skeleton was 1.03 W, and the average surface heat flux at the outer wall of the coil skeleton is displayed in Fig. 4(d).

Ideally, during the operation of the magnet, the temperature of the heat sink of the magnet suspension structure was kept at 60 K, the temperature of the magnet suspension structure was stabilized at 300 K at one end and at 8 K at the other end, and the temperature of the magnet was stabilized at 8 K. According to the finite element analysis, the simulated heat leakage was in close agreement with the estimated heat leakage, remaining within the power margin of the cryocooler. This confirms that the superconducting magnets could achieve conduction cooling.

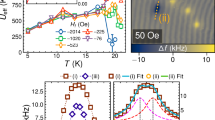

Magnetic field simulation

As illustrated in Fig. 5(a), the superconducting magnet achieves a field uniformity of 10 ppm over a 400 mm DSV. The corresponding magnetic field strength in this region is displayed in Fig. 5(b). Finite element analysis was utilized to simulate the intensity distribution of the magnetic field, as depicted in Fig. 5(c), confirming a strong and uniform field inside the magnet coils. The overall field strength for the 1–5 main coils was 7 T, with a peak of 8.35 T located between the 4th and 5th coils. These results demonstrate that the optimized coil design meets the requirements for both uniformity and strength.

Stress simulation

When the current flows through the coil, it induces corresponding electromagnetic stresses, with particular attention needed for the hoop stress in the magnet23. In order to prevent the magnet quenching due to excessive stress, finite element analysis was employed to determine the hoop electromagnetic stress distribution in the superconducting coil, as illustrated in Fig. 6(a). Under a 250 A working current, the maximum stress of 143 MPa was found in the 1–3 and 6–7 coils in the outer layers, while the stress in the 4–5 coils was uniformly distributed at 98 MPa. The modulus of elasticity of the Nb3Sn magnet is 162 GPa, and the maximum strain observed in coils 1–3 and 6–7 is 0.08%, which is well below the maximum strain limit of 0.2% for Nb3Sn. These results confirm that the electromagnetic stresses on the magnet meet the design specifications. Additionally, We must pay attention to the tension and bending stresses of the magnet to prevent the epoxy resin from rupturing and detaching, which would result in the loss of superconductivity in the coil. Finite element analysis allows for the determination of both the tension and bending stresses in superconducting coils, as illustrated in Fig. 6(b) and (c). The overall stress values for both types are below 60 MPa. The results indicate that the mechanical strength of the epoxy resin utilized in this study meets the specifications for the magnet design.

Stress distribution in the designed system. (a). Hoop stress in coils, (b). Tension stress in coils, (c). Bending stress in coils, (d). Room-temperature Dewar stress distribution, (e). Temperature distribution of the magnet suspension structure and the magnet, (f). Overall stress values of the magnet suspension structure.

The mechanical stability of the magnet is also closely linked to the pressure resistance of the room-temperature Dewar. To prevent deformation of the Dewar under internal vacuum, the stress distribution in the Dewar at the internal vacuum pressure was calculated. During normal operation, with an internal pressure of 0.1 MPa in the inner and outer Dewar barrels, the resulting stress values were 12 MPa for the inner barrel and 8 MPa for the outer barrel, as shown in Fig. 6(d).

The mechanical strength of the magnet suspension structure is critical for maintaining the magnet’s stability during operation. The suspension structure is subjected not only to its own cold shrinkage force, but also to the force induced by the cold shrinkage of the coil skeleton, driving the tie rod, as well as the gravitational force acting on the magnet. If the mechanical strength is insufficient, the entire system could fail, potentially damaging the magnet. This concern is especially important given that the coil is made of relatively brittle Nb3Sn, highlighting the importance of the mechanical strength of the magnetic suspension structure.

In the simulation, the end face of the magnet suspension structure was constrained to zero displacement. The normal stress and temperature distributions of the magnet suspension structure, considering its self-weight and the low-temperature environment during normal magnet operation, were calculated using thermo-mechanical coupling finite element analysis. The temperature at the tie rod end was stabilized at 300 K, while the coil skeleton temperature was maintained at 8 K, aligning with the predicted results. The temperature distribution is depicted in Fig. 6(e). The overall stress on the tie rod was 94 MPa, while the stress around the tie rod seat and its periphery remained below 100 MPa, ensuring that the stress levels remained within the material’s allowable limits. The stress results are shown in Fig. 6(f).

According to the results of finite element analysis, it could be concluded that the designed mechanical structure could meet the required mechanical strength for normal magnet operation.

Conclusions

This study presented the design of a 7.0 T conduction-cooled Nb3Sn magnet with a warm bore diameter of 850 mm. The seven coil bundles were sized and positioned using both linear and nonlinear optimization methods to ensure the uniformity of the magnetic field in the 400 mm imaging volume, achieving a field uniformity of 10 ppm. The mechanical behavior of the superconducting magnet was simulated using finite element analysis to ensure that both the stress and strain of the magnet met the design standards, thereby validating the accuracy of the magnet design. The mechanical properties of the cryogenic system’s structural components used to keep the magnet mechanical stability during magnet normal operation were also analyzed through finite element simulation. The simulations confirmed that the maximum stress in the mechanical structure remained within the permissible stress limits, verifying the structural integrity of the design. The HL of the cryogenic system was verified through calculations and finite element simulations, confirming that the HL of 65.64 W and 2.46 W of the system was within the 90 W and 10 W cooling capacity of cold heads (the first and second stage) of the two RDE-418D4 cryocoolers, ensuring the reliability of the cryogenic temperature. The superconducting magnet designed in this study could operate normally and stably at low temperatures, effectively achieving conduction cooling.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Hui Wang], upon reasonable request.

References

Ladd, M. E. et al. Pros and cons of ultra-high-field MRI/MRS for human application. Progress Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 109, 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnmrs.2018.06.001 (2018).

Schick, F. Whole-body MRI at high field: technical limits and clinical potential. Eur. Radiol. 15 (5), 946–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-005-2678-0 (2005).

Zhang, G. et al. A multiple layers superconducting magnet design for 9.4T magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 24 (3), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2013.2281371 (2014).

Dai, Y. et al. Structural design of a 9.4 T Whole-Body MRI superconducting magnet. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 22 (3), 4900404–4900404. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2012.2184509 (2012).

Cheng, J. et al. Progress of the 9.4-T Whole-Body MRI superconducting coils manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 28 (4), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2018.2817262 (2018).

Boulant, N. et al. In vivo imaging of the human brain with the Iseult 11.7-T MRI scanner. Nat. Methods. 21 (11), 2013–2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02472-7 (2024).

Eisenstein, M. Pushing the limits of MRI brain imaging. Nat. Methods. 21 (11), 1975–1979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02489-y (2024).

Warner, R. Ultra-high field magnets for whole-body MRI. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 29 (9), 094006. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/29/9/094006 (2016).

Cosmus, T. C. & Parizh, M. Advances in Whole-Body MRI magnets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21 (3), 2104–2109. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2010.2084981 (2011).

Hong, S. et al. Latest improvements of current carrying capability of Niobium Tin and its magnet applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 16 (2), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2005.864270 (2006).

Dietderich, D. R. & Godeke, A. Nb3Sn research and development in the USA – Wires and cables. Cryogenics 48 (7), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cryogenics.2008.05.004 (2008).

Baig, T. et al. Conduction cooled magnet design for 1.5 T, 3.0 T and 7.0 T MRI systems. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 27 (12), 125012. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/27/12/125012 (2014).

Godeke, A. A review of the properties of Nb3Sn and their variation with A15 composition, morphology and strain state. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 19 (8), R68. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/19/8/R02 (2006).

Wang, Y. et al. Electromagnetic design of a 1.5T open MRI superconducting magnet. Physica C: superconductivity and its applications, 570: p. 1353602. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2020.1353602

Wang, Y. et al. Highly shielded gradient coil design for a superconducting planar MRI system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 67 (8), 2328–2336. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2019.2959819 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. A superconducting magnet system for Whole-Body metabolism imaging. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 22 (3), 4400905–4400905. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2011.2175888 (2012).

Liang, Z. An optimal design of actively shielded MRI superconducting magnet. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 29 (2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2018.2883676 (2019).

Song, Y. et al. Globally optimal algorithm of superconducting magnet design for gyrotrons. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 32 (6), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2022.3152103 (2022).

Yin, S. et al. Epoxy resins for vacuum impregnating superconducting magnets: A review and tests of key properties. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 29 (5), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2019.2898124 (2019).

Wei, W. et al. Cryogenic performances of T700 and T800 carbon fibre- epoxy laminates. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 102 (1), 012016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/102/1/012016 (2015).

Choi, Y. S., Kim, D. L. & Shin, D. W. Cool-down characteristic of conduction-cooled superconducting magnet by a cryocooler. Physica C (Amsterdam, Neth.). 471 (21), 1440–1444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2011.05.212 (2011).

Zhu, C., Hobbs, M. J. & Willmott, J. R. An accurate instrument for emissivity measurements by direct and indirect methods. Meas. Sci. Technol. 31 (4), 044007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ab5e9b (2020).

Melville, D. & Mattocks, P. G. Stress calculations for high magnetic field coils. J. Phys. D. 5 (10), 1745. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/5/10/303 (1972).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hui Wang, Zhao Xu and Qi Chen wrote the main manuscript text and Zhichao Feng prepared figures 1, Junsheng Cheng prepared Table 1, Lei Wang prepared figures 2, Zhao Xu, Shuo Wang prepared figures 3, Jing Xiao prepared Table 2, Huafang Wu prepared figures 4, Yaohui Wang prepared figures 5, Jianhua Liu, Ce Xu prepared figures 6, Wang Qiuliang formulated the project plan and organized its implementation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Wang, H., Feng, Z. et al. Design and simulation of a 7.0 T conduction cooled superconducting magnet. Sci Rep 15, 15699 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00643-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00643-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A digital thermal protection system with data slicing

Radiation Detection Technology and Methods (2025)