Abstract

This work is a thorough investigation of mathematical modeling with an emphasis on efficiency and performance optimization. Our research is centered on the cubic–quartic nonlinear Schrödinger equation, specifically concerning birefringent fibers exhibiting nonlinearity in the cubic–quintic–septic–nonic continuum. This work makes a unique and significant addition to the field of science. We have obtained a wide range of soliton solutions for cubic–quintic optical solitons in birefringent fibers by using sophisticated mathematical techniques, most notably the modified extended mapping technique. The solitons that fall under these obtained solutions are dark, singular, bright, and combo bright-dark. Besides, we get other exact wave solutions such as singular periodic, exponential, rational, and Weierstrass elliptic doubly periodic solutions. The study presented in this publication is novel and creative, shedding light on how mathematical techniques might improve the functionality and architecture of fiber communication networks. These results are crucial for understanding pulse propagation in birefringent optical fibers governed by the cubic–quartic nonlinear Schrödinger equation, particularly when nonlinear effects extend into the cubic–quintic–septic–nonic continuum. It highlights the innovative nature of our work and highlights the relevance of our results in furthering the science of nonlinear optics and its possible applications in the real world. Graphical depictions of some of the extracted solutions are included to aid readers in physically understanding the obtained solutions’ behavior and characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The visualization of basic physical phenomena in fields like fluid mechanics, chemical reactions, electromagnetism, magneto-hydrodynamics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, optics, neuroscience, and elasticity is often achieved through the use of nonlinear partial differential equations, or NPDEs. Understanding the exact solutions to these equations is essential to comprehending the propagation of waves1,2. Chou et al.3 analyze heat conduction using Lie symmetry, solitons, and modulation instability. Kudryashov et al.4 studied cubic–quartic optical solitons under higher-order self-phase modulation. Gonzalez-Gaxiola et al.5 investigate highly dispersive solitons with a quadratic–cubic refractive index using the variational iteration method. Rehan Akber et al.6 explore Brownian motion in the stochastic Schrödinger equation via the Sardar sub-equation method. These works enhance understanding in nonlinear optics, stochastic waves, and thermal transport.

Thanks to its ability to carry massive amounts of data over long distances in a reliable and fast manner, fiber optic communications have become the backbone of the contemporary telecommunications network. The persistent advancement of fiber communication networks is propelled by the growing need for data-intensive applications, including cloud computing algorithms7, Internet of Things devices8, and video streaming programs9. Given this, understanding the complexities of these systems and optimising their performance are crucial tasks for which mathematical modelling and analysis must be used. Many models that involve NPDEs are investigated by many researchers for the seek of finding solitons by implementing several approaches and techniques such as the improved modified extended Tanh-Function method10, the sub ordinary differential equation11, the extended F-expansion method12 and many others (see13,14,15).

Ever since their discovery in the nineteenth century, solidions have been the subject of considerable investigation, revolutionizing a number of scientific and technological domains and resulting in groundbreaking discoveries in nonlinear dynamics, optics, communications, and other sectors16. Soliton solutions are one topic of special interest in mathematical fiber communications, especially in birefringent fibers. Because they can maintain their form and integrity throughout transmission, self-sustaining, non-dispersive optical pulses called soliton pulses are very attractive for long-distance communication. Birefringent fibers come with special benefits when it comes to controlling and preserving polarization because of their capacity to keep light signals polarized. Many types of soliton solutions, including single, combo-bright-dark, brilliant, and combo-singular solitons, may be studied by scientists in cubic–quintic (CQ) optical systems by using mathematical techniques17,18. Through the use of mathematical tools, scientists and engineers may develop a deeper understanding of the intricate dynamics related to light transmission, signal deterioration, interference, and other elements that affect the system’s overall performance. More dependable and effective fiber communication systems may be developed, thanks to mathematical models, which offer a quantitative foundation for system parameter design and optimization. Some valuable contributions to the study of nonlinear wave phenomena, soliton dynamics, mathematical modeling of complex physical systems, and fractional differential equations across various scientific disciplines are described briefly. Ismael et al.19 investigate autonomous multiple wave solutions and hybrid behaviors in a (3+1)-dimensional Boussinesq-type equation, which is significant for fluid mechanics. Muhammad et al.20 examine optical wave propagation in fiber optics using a nonlinear fractional Schrödinger equation, highlighting the influence of fractional derivatives on optical communication systems. Younas et al.21 focus on the solitary wave dynamics and interaction mechanisms in ultrasound imaging, modeled through a fractional nonlinear system, providing insights into medical wave applications. In22, Muhammad et al. analyze soliton solutions and their interaction properties in the Estevez-Mansfield-Clarkson equation, which appears in multiple physical fields. Their research in23 explores the propagation of fractional solitary waves in the modified Korteweg-de Vries-Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation, emphasizing parametric effects and qualitative wave characteristics. Furthermore, Muhammad et al.24 delve into the fractional impact on optical wave transmission in the extended Kairat-II equation, demonstrating how fractional-order derivatives affect nonlinear optical models. Raza et al.25 investigate complexiton and resonant multi-soliton solutions for a \((4+1)\)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation, providing insights into high-dimensional nonlinear wave interactions in optical and quantum systems. Javid et al.26 explore dual-wave resonant solutions of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation with varying nonlinearities, shedding light on wave dynamics in dispersive and nonlinear media. Kazmi et al.27 conduct a bifurcation analysis of soliton and quasi-periodic patterns in a generalized \(q\)-deformed Sinh-Gordon equation, emphasizing the role of symmetry and integrability in nonlinear systems. Finally, Raza et al.28 derive new exact periodic elliptic wave solutions for the extended quantum Zakharov-Kuznetsov equation, enhancing the understanding of nonlinear wave behavior in quantum plasmas. Together, these studies enhance the theoretical and applied understanding of nonlinear waves in diverse fields such as fluid dynamics, optics, and medical imaging.

Utilizing a powerful mathematical tool, the modified extended mapping technique (MEMT)13, these soliton solutions are found in this study. In this study, the dynamics and properties of solitons in birefringent fibers are investigated by using this approach on the cubic–quintic–septic–nonic nonlinear Schrödinger’s equation (CQSN-NLSE). For enhanced performance and efficiency, fiber communication system design and optimization can be guided by the soliton solutions generated, which offer insightful information on the behavior of the system. In addition to offering a thorough examination of the system under study and its results, the paper includes novel and unique research. This paper demonstrates the potential of mathematical modeling in fiber communications, laying the groundwork for further development and research in the design and optimization of fiber communication systems. It also contributes to the field’s ongoing development. Focusing on the CQ-NLSE in birefringent fibers with CQSN nonlinearity17,18, this study explores the intricate realm of nonlinear optical systems and is considered significant. In fields like optical signal processing, laser technology, and telecommunications, understanding this complex nonlinear behavior is crucial from a practical standpoint.

An important new concept is presented in this work. Literature that is currently accessible does not offer a thorough examination of soliton solutions inside the birefringent fibers CQSN nonlinearity model. This opens up new areas in the field of nonlinear optics. Here, we examine for the first time the effect of CQSN terms on the dynamic behavior of solitons in optical systems using the widely recognized MEMT.

A dimensionless variation of the CQ-NLSE with CQSN nonlinearity has recently been written as4:

where \(\mathcal {H}(z,t)\) defines the complex-valued wave packet’s amplitude and z, t symbolizes the the spatial and temporal variables, respectively. The first term is the evolution term, while the a and b are the 3rd and 4th order dispersion coefficients, in the given sequence. Additionally, the self-phase modulation (SPM) influences are represented by \(c_j,\ (1\le j\le 4)\).

In this article, since we treat birefringent fibers, we can split Eq. (1) into the following coupled NLSEs (CNLSEs)17:

where the functions \(\phi = \phi (z, t)\) and \(\psi = \psi (z, t)\) describe wave profiles, whereas the first terms relate to linear temporal evolutions. The coefficients \(\alpha _i\) and \(\beta _i,\ (i = 1, 2)\) reflect the 3rd and 4th order dispersions, respectively. The constants \(a_{i2},\ b_{i2},\ b_{i3},\ c_{i2},\ c_{i3},\ c_{i4}, d_{i2},\ d_{i3},\ d_{i4},\) and \(d_{i5},\ (i = 1, 2)\) represent the coefficients of the cross-phase modulation (XPM) terms. The coefficients of the SPM terms are \(a_{i1},\ b_{i1},\ c_{i1}\), and \(d_{i1}, \ (i = 1, 2)\).

The novelty of this work lies in deriving a broader class of solutions than previously reported, including singular, periodic, and elliptic function solutions, expanding the known solution space. Unlike earlier studies limited to cubic–quintic or cubic–septic models, this research incorporates ninth-order nonlinearities, providing a more complete understanding of extreme nonlinear regimes in birefringent fibers, which is essential for advanced optical communication and fiber laser technologies. Each solution is substituted back into the original cubic–quartic nonlinear Schrödinger equation to confirm that it satisfies the equation exactly.

Below is the structure of this paper: The exact solutions for the suggested coupled system in Eqs. (2)–(3) are derived after a brief discussion of the concept’s mathematical underpinnings and recent application. Mathematical preliminaries for the proposed method” section provides a summary of the main elements of the suggested strategy. In addition to displaying all of the data, “Novel solutions extraction for the proposed coupled system” section explains the many dynamic wave shapes that make up the novel soliton solutions when implementing the MEMT. In “Graphical simulation of some retrieved solutions” section, graphical 2D, 3D, and contour drawings of several obtained solutions are shown. “Conclusion” section presents some inferences drawn from the data acquired and some conclusive remarks.

Mathematical preliminaries for the proposed method

This section is divided into two parts. General detailed steps of the proposed technique are presented in the first part. Finally, we mention the advantages of the applied technique compared to some other methods in the literature in the last subsection.

General algorithm of the MEMT

The key components of the MEMT that will be used in section 3 are presented in this section13.

If we assume to have an NPDE of the following form :

where \({\mathfrak {Z}}\) denotes a polynomial function of \({\mathfrak {R}}(x,t)\) and its corresponding partial derivatives with respect to the two-dimensional time and space.

Algorithm-(I): The next travelling wave transformation will be used to solve Eq. (4):

where \(\kappa\) denotes the speed of the wave.

The transformation of Eq. (5) into Eq. (4) yields the following nonlinear ordinary differential equation (NODE):

Algorithm-(II): We suggest that the general solution of Eq. (6) is:

where \(\mathbb {A}_j,\mathbb {B}_{-j},\theta _j,\mathbb {C}_{-j}\) represent real-valued constants that will be estimated and the function \(\mathcal {W}(\zeta )\) obeys the following constraint:

where \(\tau _i,\ (i = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6)\) are constants. Many types of solutions can be extracted from Eq. (8) by putting \(\tau _0,\tau _1,\tau _2,\tau _3,\tau _4,\tau _6\) with differnt values as follows:

Case 1: When \(\tau _0=\tau _1=\tau _3=\tau _6=0\), the following solutions are raised:

Case 2: When \(\tau _1=\tau _3=\tau _6=0, \tau _0=\dfrac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), the following solutions are raised:

Case 3: When \(\tau _3=\tau _4=\tau _6=0\), the following solutions are raised:

Case 4: When \(\tau _0=\tau _1=\tau _2=\tau _6=0\), the following solution is raised:

Case 5: When \(\tau _0=\tau _1=\tau _6=0\), the following solutions are raised:

Case 6: When \(\tau _2=\tau _4=\tau _6=0\), the following solution is raised:

Case 7: When \(\tau _1=\tau _3=\tau _6=0\), the following solutions are raised:

No. | \(\tau _0\) | \(\tau _2\) | \(\tau _4\) | \(\mathcal {W}(\zeta )\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 1 | \(-(1+m^2)\) | \(m^2\) | \(\text {cd}(\zeta ,m)\) or \({{\,\text{sn}\,}}(\zeta ,m)\) |

2 | \(m^2-1\) | \(-m^2+2\) | \(-1\) | \({{\,\text{dn}\,}}(\zeta ,m)\) |

3 | \(-m^2\) | \(2m^2-1\) | \(-m^2+1\) | \({{\,\text{nc}\,}}(\zeta ,m)\) |

4 | \(-1\) | \(-m^2+2\) | \(m^2-1\) | \({{\,\text{nd}\,}}(\zeta ,m)\) |

5 | \(m^2-2m^3+m^4\) | \(-\dfrac{4}{m}\) | \(-1+6m-m^2\) | \(\dfrac{m \text {dn}(\zeta |m) \text {cn}(\zeta |m)}{1+m \text {sn}(\zeta |m)^2}\) |

6 | \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) | \(\frac{1}{2} m^2-1\) | \(\dfrac{m^4}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{\text {sn}(\zeta |m)}{1+\text {dn}(\zeta |m)}\) or \(\dfrac{\text {cn}(\zeta |m)}{\sqrt{1-m^2}+\text {dn}(\zeta |m)}\) |

Algorithm-(III): Equation (6) may be utilised to compute the integer \(\mathbb {M}\), utilising the idea of homogeneous balancing the nonlinearity and the dispersion in the resultant ODE.

Algorithm-(IV): After plugging the suggested solution into Eq. (5) using Eq. (8) into Eq. (6), we equalize the coefficients of \(\mathcal {W}^{'j}(\zeta )\mathcal {W}^{i}(\zeta )\) (\(j=0,1\); \(i=0,\pm 1,\pm 2,...\)) to zero and obtain a set of nonlinear algebraic equations (NLAEs) for \(\mathbb {A}_j,\mathbb {B}_{-j},\theta _j,\mathbb {C}_{-j} ~\text {and}~\kappa\), which will be solved using the Wolfram Mathematica program. From there, we can estimate the used unknowns \(\mathbb {A}_j,\mathbb {B}_{-j},\theta _j,~\text {and}~\mathbb {C}_{-j}\). Following that, it is possible to derive many precise solutions for Eq. (4).

Advantages of the applied technique

The MEMT has several advantages over traditional methods for solving nonlinear differential equations. Unlike the Inverse Scattering Transform29, which is limited to integrable equations and requires intricate spectral analysis, MEMT provides a more direct and adaptable approach. Compared to Hirota’s Bilinear Method30, which involves tedious bilinear transformations and perturbative expansions, MEMT simplifies the derivation of exact solutions. Unlike Lie Symmetry Analysis31, which demands extensive group-theoretic computations and is often limited to finding symmetry-invariant solutions, MEMT systematically generates multiple types of solutions, including solitons, periodic, and elliptic function solutions. Its efficiency and versatility make it a valuable tool in nonlinear wave analysis.

Novel solutions extraction for the proposed coupled system

The solutions of Eqs. (2)–(3) may be obtained by assuming the following wave transformation:

and

where \(\mathcal {P}_1(\zeta )\) and \(\mathcal {P}_2(\zeta )\) denote the wave’s solution amplitude, and \(\mathcal {K},\ \rho ,\ \Delta\) and \(\omega\) denote the frequency, velocity of the soliton, phase shift constant and wave number in the mentioned sequence.

Using the transformation described by Eqs. (9)–(11), after that, Eqs. (2)–(3) will be transformed into the subsequent system of NODEs, then separating the real and imaginary parts yield:

Real parts:

and the imaginary parts are:

By integrating Eqs. (14)–(15) with respect to \(\zeta\) once with neglecting the constant of integration, and then inserting them in Eqs. (12)–(13), respectively, we get:

Now, let’s set

Then, Eqs. (16)–(17) can be written as:

So, by comparing the coefficients of Eqs. (19)–(20), they are equivalent by providing the following constraints:

Then, we can find the wave number from Eq. (21) to be

Then Eq. (19) can be expressed as follows:

where \(\mathcal {L}_i\), \((i=1,3,5,7,9)\) represent constants and expressed as:

At this stage, we have to assume that

then, we can write Eq. (27) as:

According to the proposed technique discussed in section 2, by applying the balance between \(\mathcal {X}^3 \mathcal {X}^{(4)}\) and \(\mathcal {X}^8\), we find that \(\mathbb {M}=1\). From Eq. (7), the solution of Eq. (30) can be formulated as:

assuming that \(\mathbb {A}_1\), \(\mathbb {B}_1\), and \(\mathbb {C}_1\) are all unknown constants, they may be estimated by concurrently applying the restrictions \(\mathbb {A}_1\), \(\mathbb {B}_1\), and \(\mathbb {C}_1\ne 0\).

The following results may be obtained by solving the system of NLAEs created by inserting Eqs. (31) and (8) into Eq. (30) with the help of the Wolfram Mathematica program, grouping coefficients of comparable powers and setting them all to zero:

Result-(1): When \(\tau _0 =\tau _1 = \tau _3 =\tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), these are the sets of solutions that we discovered:

-

Set (1.1):

\(\mathbb {B}_1=\mathcal {L}_7=\mathcal {L}_3= 0,\ \mathbb {A}_1= \frac{\root 4 \of {-105} \sqrt{-\tau _4}}{2 \root 4 \of {\mathcal {L}_9}},\) \(\mathcal {L}_5= \frac{-13\tau _2}{2} \sqrt{-\frac{3 \mathcal {L}_9}{35}},\ \mathcal {L}_1= -\frac{\tau _2^2}{16}.\)

-

Set (1.2):

\(\displaystyle \mathbb {B}_1=\mathcal {L}_7=\mathcal {L}_3= 0,\ \mathbb {A}_1= \frac{\root 4 \of {-105} \sqrt{\tau _4}}{2 \root 4 \of {\mathcal {L}_9}},\) \(\mathcal {L}_5= \frac{13\tau _2}{2} \sqrt{-\frac{3 \mathcal {L}_9}{35}},\ \mathcal {L}_1= -\frac{\tau _2^2}{16}.\)

According to set (1.1), the solutions of Eqs. (2)–(3) can be stated as:

-

(1.1)

If \(\tau _2 > 0,\ \tau _4 < 0\) and \(\mathcal {L}_9<0\), then:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{1.1}(z,t)= \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \text {sech}\left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(32)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{1.1}(z,t)= \Omega \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \text {sech}\left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(33)these solutions represent bright soliton solutions.

According to set (1.2), the solutions of Eqs. (2)–(3) can be stated as:

-

(1.2)

If \(\tau _2 < 0,\ \tau _4 > 0\) and \(\mathcal {L}_9<0\), the solutions will be:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{1.2,1}(z,t)=\left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{-\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \sec \left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(34)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{1.2,1}(z,t)=\Omega \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{-\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \sec \left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(35)or

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{1.2,2}(z,t)=\left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{-\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \csc \left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(36)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{1.2,2}(z,t)=\Omega \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{-\tau _2} \root 4 \of {-\frac{105}{\mathcal {L}_9}} \csc \left[ (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(37)these solutions represent the singular periodic solutions.

Result-(2): When \(\tau _1 = \tau _3 = \tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\) and \(\tau _0 = \frac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), this is the set of solutions that we gained:

Based on the recovered solutions’ set, we may state the following solutions:

If \(\tau _2> 0,\ \tau _4 > 0\) and \(\mathcal {L}_9<0\), we get singular periodic solutions:

Result-(3): When \(\tau _3=\tau _4 = \tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), this is the set of solutions that we gained:

If \(\tau _2 > 0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _1^2}{4 \tau _2},\ \mathcal {L}_9<0,\ \tau _1 \tau _2 \mathcal {L}_7<0\) and \(\tau _1\ne 2 \tau _2 e^{\sqrt{\tau _2} (z-\rho t)}\), then, the solutions are:

these solutions are exponential ones.

Result-(4): When \(\tau _0 = \tau _1 = \tau _2 = \tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), then, we obtain:

Then, the solutions are:

which provide rational wave solutions in the constraints that \(\mathcal {L}_9<0,\ \tau _4<0\) and \(\tau _3^2 (z-\rho t)^2-4 \tau _4\ne 0\).

Result-(5): When \(\tau _0 = \tau _1 = \tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), then, we discover:

Then, the solutions will be:

-

(5.1)

If \(\tau _2 > 0,\ \tau _3^2=4 \tau _2 \tau _4\) and \(\mathcal {L}_3>0\), then, the solutions are:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{5.1}(z,t)=\frac{1}{2} \tau _2 \left( \frac{5 \left( \tanh \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] +1\right) }{\mathcal {L}_3}\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(44)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{5.1}(z,t)=\frac{\Omega }{2} \tau _2 \left( \frac{5 \left( \tanh \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] +1\right) }{\mathcal {L}_3}\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(45)these solutions are the dark solitons, or we can obtain singular soliton solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{5.2}(z,t)=\frac{1}{2} \tau _2 \left( \frac{5 \left( \coth \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] +1\right) }{\mathcal {L}_3}\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(46)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{5.2}(z,t)=\frac{\Omega }{2} \tau _2 \left( \frac{5 \left( \coth \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] +1\right) }{\mathcal {L}_3}\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}. \end{aligned}$$(47) -

(5.2)

If \(\tau _2> 0,\ \tau _4> 0,\ \tau _3^2\ne 4 \tau _2 \tau _4,\ \tau _3 \mathcal {L}_3>0\) and \(\tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tanh \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\tau _2} (z-\rho t)\right) \ne 0\), then, the solutions are:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{5.3}(z,t)=\frac{1}{2} \tau _2 \sqrt{\frac{5 \tau _3 \text {sech}^2\left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] }{\mathcal {L}_3 \left( \tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tanh \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] \right) }}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(48)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{5.3}(z,t)=\frac{\Omega }{2} \tau _2 \sqrt{\frac{5 \tau _3 \text {sech}^2\left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] }{\mathcal {L}_3 \left( \tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tanh \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{\tau _2}\right] \right) }}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(49)these solutions represent combo bright-dark soliton solutions.

-

(5.3)

If \(\tau _2 < 0,\ \tau _4> 0,\ \tau _3^2\ne 4 \tau _2 \tau _4,\ \tau _3 \mathcal {L}_3>0\) and \(\tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tan \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{-\tau _2} (z-\rho t)\right) \ne 0\), then:

$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \phi _{5.4}(z,t)=\frac{1}{2} \tau _2 \sqrt{\frac{5 \tau _3 \text {sec}^2\left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] }{\mathcal {L}_3 \left( \tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tan \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) }}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(50)$$\begin{aligned} \displaystyle \psi _{5.4}(z,t)=\frac{\Omega }{2} \tau _2 \sqrt{\frac{5 \tau _3 \text {sec}^2\left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] }{\mathcal {L}_3 \left( \tau _3-2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _4} \tan \left[ \frac{1}{2} (z-\rho t)\sqrt{-\tau _2}\right] \right) }}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(51)these solutions represent singular periodic solutions.

Result-(6): When \(\tau _2=\tau _4=\tau _6 = \mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), then, we gain:

So, we can have the following Weierstrass elliptic doubly periodic solutions:

where \(\mathcal {L}_9<0\) and \(\mathcal {L}_3\tau _3 >0\).

Result-(7): When \(\tau _1 = \tau _3 =\tau _6 =\mathbb {A}_0=\mathbb {C}_1= 0\), then, these are the sets of solutions that we discovered:

-

Set (7.1):

\(\displaystyle \mathbb {B}_1=\mathcal {L}_3=\mathcal {L}_7=\tau _0=0,\ \mathbb {A}_1= \sqrt{-\frac{39 \tau _2 \tau _4}{8 \mathcal {L}_5}},\ \mathcal {L}_1= -\frac{\tau _2^2}{16},\ \mathcal {L}_9= -\frac{140 \mathcal {L}_5^2}{507 \tau _2^2}.\)

-

Set (7.2):

\(\displaystyle \mathcal {L}_3=\mathcal {L}_7= 0,\ \mathbb {A}_1= -\sqrt{\frac{39 \tau _2 \tau _4}{4 \mathcal {L}_5}},\ \mathbb {B}_1= -\tau _2 \sqrt{\frac{39 \tau _2}{16 \tau _4 \mathcal {L}_5}},\ \mathcal {L}_1= -\frac{\tau _2^2}{4},\ \mathcal {L}_9= -\frac{35 \mathcal {L}_5^2}{507 \tau _2^2},,\tau _0= \frac{\tau _2^2}{4 \tau _4}.\)

As per the solution set (7.1), the solutions can be expressed as follows:

-

(7.1,1)

If \(\tau _0=m^2-1,\ \tau _2=2-m^2,\ \tau _4=-1,\) and \(\mathcal {L}_5>0\), then, the solutions are:

$$\begin{aligned} \phi _{7.1,1}(z,t)= \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{39}{2 \mathcal {L}_5}} \text {sech}[z-\rho t]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(54)$$\begin{aligned} \psi _{7.1,1}(z,t)= \Omega \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{39}{2 \mathcal {L}_5}} \text {sech}[z-\rho t]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(55)these solutions represent bright soliton solutions.

-

(7.1,2)

If \(\tau _0=-m^2,\ \tau _2=2 m^2-1,\ \tau _4=1-m^2,\) and \(\mathcal {L}_5>0\), then, the solutions are:

$$\begin{aligned} \phi _{7.1,2}(z,t)= \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{39}{2 \mathcal {L}_5}} \text {sec}[z-\rho t]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(56)$$\begin{aligned} \psi _{7.1,2}(z,t)= \Omega \left( \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\frac{39}{2 \mathcal {L}_5}} \text {sec}[z-\rho t]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(57)these solutions are singular periodic solutions.

As per the solution set (7.2), the solutions can be expressed as follows:

-

(7.2,1)

If \(\tau _0=1,\ \tau _2=-m^2-1,\ \tau _4=m^2,\) and \(\mathcal {L}_5<0\), then, we raise singular soliton solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} \phi _{7.2,1}(z,t)=\root 4 \of {78} \left( \sqrt{-\frac{1}{\mathcal {L}_5}} \text {csch}[2 (z-\rho t)]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}, \end{aligned}$$(58)$$\begin{aligned} \psi _{7.2,1}(z,t)=\Omega \root 4 \of {78} \left( \sqrt{-\frac{1}{\mathcal {L}_5}} \text {csch}[2 (z-\rho t)]\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}}e^{i (-\mathcal {K} z+\omega t +\Delta )}. \end{aligned}$$(59)

Graphical simulation of some retrieved solutions

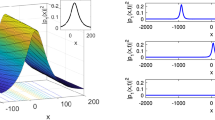

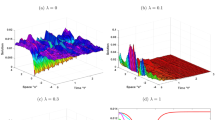

Equations (2)–(3) yielded many families of solutions when specific values were assigned to the parameters. This investigation has, therefore, led to several previously unpublished original and revised results. The 3D, contour, and 2D figures of certain specific solutions are displayed in order to let the reader fully understand the physical structures of some extracted solutions that will be provided. The bright soliton solution of Eq. (32) is plotted in Fig. 1 where the parameter’s values are \(\alpha _1=0.7,\ \mathcal {K}=0.5,\ \beta _1=-0.6,\ \beta _2=0.8,\ \alpha _2=0.7,\ \rho =0.5,\ \Omega =0.6,\ d_{11}=0.5,\ d_{12}=0.75,\ d_{13}=0.6,\ d_{14}=0.7,\ d_{15}=0.8,\ \Delta =0.7,\) and \(-15<x<15\). This solution depicts a bright soliton propagating over a nonlinear medium while keeping its localised form over time. The absence of oscillatory tails points to a basic soliton rather than a higher-order or periodic structure. This behaviour has applications in nonlinear optics, optical fibre communications, and wave dynamics. Eq.(34) shows a singular periodic solution which is drawn in Fig. 2 with \(\alpha _1=0.7,\ \mathcal {K}=0.6,\ \beta _1=-0.7,\ \beta _2=0.9,\) \(\alpha _2=0.8,\ \rho =0.6,\ \Omega =0.7,\ d_{11}=0.85,\ d_{12}=0.7,\ d_{13}=0.7,\) \(d_{14}=0.6,\ d_{15}=0.7,\ \Delta =0.8,\) and \(-8<x<8\). This solution is a periodic wave train rather than a single soliton, with steady and repeating oscillations. Such solutions occur in birefringent fibres and nonlinear media where energy distribution is periodic rather than localised, making them useful for optical signal processing, waveguides, and nonlinear wave interactions. Figure 3 displays a dark soliton solution of Eq. (44) with \(\alpha _1=-0.5,\ \mathcal {K}=0.7,\ \beta _1=0.8,\) \(\beta _2=-0.7,\ \alpha _2=-0.8,\ \rho =0.7,\) \(\Omega =0.7,\) \(a_{11}=0.5,\) \(a_{12}=0.7,\) \(\Delta =0.8,\) and \(-15<x<15\). This solution is a dark soliton solution, which is an important structure in nonlinear optics, fluid mechanics, and phase transition models. The sudden shift in amplitude indicates shock-wave dynamics, which are common in fibre optics, plasma physics, and condensed matter systems. Additionally, Eq.(48) is a combo bright-dark soliton solution that is plotted in Fig. 4 when \(\alpha _1=-0.7,\ \mathcal {K}=0.7,\ \beta _1=0.6,\) \(\beta _2=-0.8,\ \alpha _2=0.6,\) \(\rho =0.7,\) \(\Omega =0.8,\) \(a_{11}=0.5,\) \(a_{12}=0.7,\)\(\rho =0.7,\ \Omega =0.8,\ a_{11}=0.5,\ a_{12}=0.7,\) \(\Delta =0.85,\ \tau _4=0.7,\ \tau _3=0.9,\) and \(-15<x<15\).

Simulation of the solution of Eq. (32).

Simulation of the solution of Eq. (34).

Simulation of the solution of Eq. (44).

Simulation of the solution of Eq. (48).

Conclusion

We take on a leading position in the field of nonlinear optics with our study. Our main goal is to thoroughly investigate soliton solutions as they relate to birefringent fibers with CQSN nonlinearity, using the framework of the CQ-NLSE model. This unexplored field adds something unique and important to the body of knowledge in science. In order to understand the complexities of fiber communication networks and optimize their performance, we emphasize repeatedly in this study how crucial mathematical modeling and analysis are. Researchers and engineers may comprehend the dynamics and properties of optical systems by skillfully applying mathematical tools. These discoveries promise improved performance and efficiency and have practical implications for the development of fiber communication networks. Key conclusions include the impact of higher-order self-phase modulation on soliton structure, the role of non-Kerr nonlinearities in shaping pulse dynamics, and the conditions for stable propagation. We found a large number of new soliton solutions. The retrieved solutions include singular, dark, bright, and combo bright-dark solitons. Also, we get numerous exact wave solutions, including rational, exponential, singular periodic, and Weierstrass elliptic double periodic solutions. With the fiber optic communications business developing so quickly, it is impossible to exaggerate the value of mathematical modelling and analysis. This dynamic interaction fosters creativity, maximizes system efficiency, and effectively handles the ever-increasing demands of contemporary telecommunications. More sophisticated fiber communication technologies are made possible by the combination of practical technical solutions and mathematical methodologies, which effectively meet the demands of our data-driven society. In order to clarify the physical nature of some solutions, graphic representations were also added. Since this model has never been examined using the suggested method, the answers we retrieved for our study report are unique. The method’s aptitude for handling NPDEs and its ease of use, efficacy, and success rate are further indications of its trustworthiness.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

Kukkar, A. et al. Optical solitons for the concatenation model with Kurdryashov’s approaches. Ukrain. J. Phys. Opt. 24(2), 56 (2023).

Ahmed, K. K., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Unveiling optical solitons and other solutions for fourth-order (2+ 1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger equation by modified extended direct algebraic method. J. Opt. 7, 1–13 (2024).

Chou, D., Ifrah, I., Rehman, H. U., Khalil, O. H. & Osman, M. S. Heat Conduction Dynamics: A Study of Lie Symmetry, Solitons, and Modulation Instability (Rendiconti Lincei, Scienze Fisiche e Naturali, 2025).

Kudryashov, N. A., Biswas, A., Kara, A. H. & Yıldırım, Y. Cubic-quartic optical solitons and conservation laws having cubic–quintic–septic–nonic self-phase modulation. Optik 269, 169834 (2022).

Gonzalez-Gaxiola, O., Biswas, A., Ekici, M. & Khan, S. Highly dispersive optical solitons with quadratic-cubic law of refractive index by the variational iteration method. J. Opt. 7, 1–8 (2022).

Rehan Akber, H. U., Wazwaz, A. M., Alshehri, H. M. & Osman, M. S. Analysis of Brownian motion in stochastic Schrödinger wave equation using Sardar sub-equation method. Optik 289, 171305 (2023).

Ogundipe, D. O. Conceptualizing cloud computing in financial services: Opportunities and challenges in Africa-US contexts. Comput. Sci. IT Res. J. 5(4), 757–767 (2024).

Hasan, M. K., Weichen, Z., Safie, N., Ahmed, F. R. A. & Ghazal, T. M. A survey on key agreement and authentication protocol for Internet of Things application. IEEE Access (2024).

Evens, T., Henderickx, A. & Conradie, P. Technological affordances of video streaming platforms: Why people prefer video streaming platforms over television. Eur. J. Commun. 39(1), 3–21 (2024).

Khalifa, A. S., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Retrieval of optical solitons in fiber Bragg gratings for high-order coupled system with arbitrary refractive index. Optik 287, 171116 (2023).

Osman, M. S., Machado, J. & Baleanu, D. On nonautonomous complex wave solutions described by the coupled Schrödinger–Boussinesq equation with variable-coefficients. Opt. Quant. Electron. 50, 73 (2018).

Khalifa, A. S., Ahmed, H. M., Badra, N. M. & Rabie, W. B. Exploring solitons in optical twin-core couplers with Kerr law of nonlinear refractive index using the modified extended direct algebraic method. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(6), 1060 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K. et al. Diverse exact solutions to Davey–Stewartson model using modified extended mapping method. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 29(5), 983–1002 (2024).

Nithyanandan, K. Soliton physics in India: A tribute to the late K. Porsezian. Opt. Commun. 553, 130078 (2024).

Martel, Y. Asymptotic stability of small standing solitary waves of the one-dimensional cubic–quintic Schrödinger equation. Inventiones Mathematicae 8, 1–76 (2024).

Zhong, Y., Triki, H. & Zhou, Q. Bright and kink solitons of time-modulated cubic–quintic–septic–nonic nonlinear Schrödinger equation under space-time rotated pt-symmetric potentials. Nonlinear Dyn. 112(2), 1349–1364 (2024).

AlQahtani, S. A., Alngar, M. E., Shohib, R. & Alawwad, A. M. Enhancing the performance and efficiency of optical communications through soliton solutions in birefringent fibers. J. Opt. 6, 1–11 (2024).

Yıldırım, Y., Biswas, A., Khan, S., Mahmood, M. F. & Alshehri, H. M. Highly dispersive optical soliton perturbation with Kudryashov’s sextic-power law of nonlinear refractive index. Ukr. J. Phys. Opt. 23(1), 24–29 (2022).

Ismael, H. F., Sulaiman, T. A., Younas, U. & Nabi, H. R. On the autonomous multiple wave solutions and hybrid phenomena to a (3+1)-dimensional Boussinesq-type equation in fluid mediums. Chaos Solitons Fractals 187, 115374 (2024).

Muhammad, J., Younas, U., Nasreen, N., Khan, A. & Abdeljawad, T. Multicomponent nonlinear fractional Schrödinger equation: On the study of optical wave propagation in the fiber optics. Part. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 11, 100805 (2024).

Younas, U. et al. On the study of solitary wave dynamics and interaction phenomena in the ultrasound imaging modelled by the fractional nonlinear system. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 26080 (2024).

Muhammad, J., Nasreen, N., Hussain, E., Younas, U. & Alsubaie, A. S. On the study of analytical soliton solutions and interaction aspects to the Estevez–Mansfield–Clarkson equation arising in diversity of fields. Phys. Scr. 99(11), 115221 (2024).

Muhammad, J. et al. Analysis of fractional solitary wave propagation with parametric effects and qualitative analysis of the modified Korteweg-de Vries-Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 19736 (2024).

Muhammad, J., Rehman, S. U., Nasreen, N., Bilal, M. & Younas, U. Exploring the fractional effect to the optical wave propagation for the extended Kairat-II equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 6, 1–12 (2024).

Raza, N., Kaplan, M., Javid, A. & Inc, M. Complexiton and resonant multi-solitons of a (4+ 1)-dimensional Boiti–Leon–Manna–Pempinelli equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54, 1–16 (2022).

Javid, A., Seadawy, A. R. & Raza, N. Dual-wave of resonant nonlinear Schrödinger’s dynamical equation with different nonlinearities. Phys. Lett. A 407, 127446 (2021).

Kazmi, S. S. et al. The analysis of bifurcation, quasi-periodic and solitons patterns to the new form of the generalized q-deformed Sinh–Gordon equation. Symmetry 15(7), 1324 (2023).

Raza, N., Abdullah, M., Butt, A. R., Murtaza, I. G. & Sial, S. New exact periodic elliptic wave solutions for extended quantum Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 50, 1–17 (2018).

Xu, C., Xu, T., Li, M. & Huang, Y. Inverse scattering transform for the focusing PT-symmetric nonlinear Schrödinger equation with nonzero boundary conditions: Higher-order poles and multi-soliton solutions. Physica D 472, 134466 (2025).

Yang, L. & Gao, B. Multiple solitons solutions, lump solutions and rogue wave solutions of the complex cubic Ginzburg–Landau equation with the Hirota bilinear method. Indian J. Phys. 99(1), 221–228 (2025).

Mandal, S., Sil, S. & Ghosh, S. On the Lie symmetry analysis of three-dimensional perturbed shear flows. Chaos Solitons Fractals 191, 115875 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K and N.A: Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. H.M.: Writing-original draft, Software, Conceptualization. S.B.: Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. M.S.: Supervision, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, K.K., Alsahafi, N.A., Ahmed, H.M. et al. Diverse solitons wave structures for coupled NLSEs in birefringent fibers with higher nonlinearities using the modified extended mapping algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 17047 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00668-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00668-1