Abstract

Influenza poses a global health threat. With drug-resistant strains emerging, there is an urgent need for effective antiviral drugs. This study explores antiviral potential of flavonoids against influenza A virus (IAV) and their mechanism of action. By utilizing in silico docking as a screening approach, diosmin, orientin, and fisetin were identified as flavonoids with the strongest interactions with viral proteins. Out of them, diosmin was found to effectively inhibit IAV replication in vitro, particularly at the attachment and post-entry stages, with significant inhibition observed at 0-h post-infection (hpi) and 2 hpi, while also demonstrated prophylactic activity, peaking at − 2 hpi. Following that, diosmin significantly increases the expression of antiviral genes, which may relate to the discovery of its prophylactic activity. Proteomics analysis showed that diosmin treatment during the post-entry stage of IAV replication reduced viral protein levels, confirming its antiviral activity at this point. Additionally, diosmin also modulated host proteins related to innate immunity, inducing type I interferon and anti-inflammatory responses during the infection. These findings provide preliminary evidence of diosmin’s antiviral and prophylactic activity against IAV, paving the way for further research on its mechanism of action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) is the most common influenza virus infecting humans and animals compared to other strains such as B, C and D, in which IAV also has the highest potential to cause global pandemics1. During the pandemic influenza of 1918–1919, it is estimated that there were about 50–100 million deaths worldwide2. Subsequent pandemics caused by the new IAV subtypes in 1957–1958, 1968–1969 and 2009–2010 resulted in 1–4 million, 1–4 million and 100 000 to 400 000 deaths, respectively3. Meanwhile, a study by Iuliano et al.4 from 1999 to 2015 suggested that there will be 3–5 million serious seasonal influenza cases globally each year, leading to an estimated 290 000–650 000 deaths yearly. Among the subtypes of IAV, H1N1 is responsible for pandemic and seasonal epidemic outbreaks and poses a continuous threat to public health1. Generally, IAV is an enveloped, single-stranded, and negative-sense RNA virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae. IAV has eight RNA segmented genome encoding 11 viral proteins: hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), two matrix proteins (M1 and M2), RNA polymerases (PA, PB1, PB2 and PB-F2), nucleoprotein (NP) and two nonstructural proteins (NS1 and NS2)5. Every single IAV protein is essential for viral replication. For this reason, antiviral strategies target these viral proteins to reduce the impact of IAV infection6. Amantadine, rimantadine, oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir and laninamivir are among the anti-influenza drugs that have been commercialized. However, IAVs have developed drug-resistant ability, and the drugs have caused side effects on the health of experimental subjects1. Recently, there was a new FDA-approved antiviral drug for influenza named baloxavir marboxil (BAM) in 2018. Still, its use in clinical practice is complicated by its higher cost than oseltamivir, and there has been evidence of BAM resistance in Japan after its introduction6. Therefore, searching for safe and effective antiviral candidates against IAV remains an urgent priority.

Flavonoids, which are plant-derived natural products, possess potent antiviral properties7. Notably, apigenin8, baicalein9, catechin10, kaempferol11, luteolin12, and quercetin1,13 are among the flavonoids that have been reported to exhibit antiviral effects against IAV. Diosmin, a flavone glycoside found in citric fruits, has demonstrated potent antiviral activity against rotavirus14. This antiviral effect is thought to be related to the specific structure of the sugar moiety present in diosmin. Furthermore, unpublished data suggests that diosmin also exhibits antiviral activity against dengue virus type 2 (DENV-2) through the inhibition of the E glycoprotein of DENV-215. Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to assess the antiviral potential of diosmin and other selected flavonoids against H1N1 of IAV. Through a docking platform screening, we identified diosmin, fisetin, and orientin as the top three flavonoids with the highest probability of binding to the viral proteins of H1N1. Moreover, our findings indicate that diosmin exhibits superior antiviral activity compared to fisetin and orientin, likely by interfering with the attachment of H1N1 to A549 cells and the subsequent post-entry phase. This is as effective as vitexin16 and 8-prenylnaringenin17, which are known to inhibit both the attachment and post-entry phases of IAV replication, as observed in prior in vitro studies. Furthermore, this study provides insights into the possible antiviral mechanisms of diosmin, as highlighted by LCMS-based proteomics analysis. To the best of our knowledge, the anti-influenza potential of diosmin is still unknown, indicating a valuable opportunity for future research to extensively explore and evaluate its effectiveness against influenza.

Results

Molecular docking screening

The cavity-detection guided blind docking using the CB-Dock2 webserver was used as the screening strategy for evaluating flavonoids as potential antiviral candidates against the H1N1 influenza A virus. A flavonoid compound library provided by Selleckchem (USA) was selected for the screening process. From a total of 240 flavonoids in the library, 14 flavonoids without rotatable bond, 21 flavonoids with less than two hydrogen bond acceptors and 97 flavonoids with less than four hydrogen bond donors were removed. Of the 108 flavonoids qualified for further screening, 98 flavonoids dealing with influenza virus or no antiviral against other viruses were removed from the list. Ultimately, 10 flavonoids with antiviral potential against viruses except influenza virus were chosen and subsequently subjected to molecular docking. The docking simulations involved the binding of flavonoids to the IAV structural and non-structural proteins, namely HA (4EDB), NA (3NSS), and NS1 (3RVC). These viral proteins were selected based on their significant role in IAV virulence18,19,20,21 and evasion of host immunity22,23,24,25,26. The results presenting the binding affinity (kcal/mol) between each flavonoid and IAV proteins are tabulated in Table 1.

The findings revealed that diosmin, orientin and fisetin exhibited stronger binding against IAV proteins compared to the other flavonoids tested. In comparison between diosmin, orientin and fisetin, diosmin demonstrated stronger binding against NS1, HA and NA proteins than orientin and fisetin. Both orientin and fisetin exhibited approximately the same binding affinity of − 6.6 kcal/mol and − 6.4 kcal/mol, respectively, when docked against NS1 protein. In contrast, diosmin exhibited the strongest binding with a value of − 8.4 kcal/mol against NS1. For docking against HA, the diosmin-HA conformation showed a highest binding affinity of − 10.6 kcal/mol compared to the orientin-HA conformation (− 9.2 kcal/mol) and fisetin-HA conformation (− 8.1 kcal/mol). Similar trends were observed for the binding of these ligands against NA, with diosmin, orientin and fisetin exhibiting binding affinities of − 10.0 kcal/mol, − 8.3 kcal/mol and − 7.7 kcal/mol, respectively. Due to their strong binding affinity with NS1 and HA viral proteins, diosmin, orientin and fisetin were selected for further in vitro assays. To understand the reasons for the high binding affinity of these selected flavonoids, we examined the 3D structures of the complexes formed between the flavonoids and viral proteins as shown in Table 2.

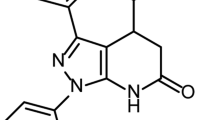

Based on the flavonoid structures in Table 2, it is shown that diosmin has more of hydroxyl group (OH) and embedded oxygen (O) compared to orientin and fisetin. Interestingly, diosmin exhibits this structural component that interacts with many viral residues (NS1: R88, L90, V136, D139, R140, L141, E142, T143, H169, T170, A171, E172, K175, R200, F201, A202, W203; HA: N71, K72, L73, E74, G93, H94, F95, A96, D97, Y98, E99, Q104, S202, H204, Y205, S206, R207, F209, Y229, W230, T231, L232, L233; NA: A180, I222, R224, T225, E227, S246, E276, E277, R292, N294, N325, N347, S370, R371, N372, W403, S404, Y406, I427, R430, P431, K432) via hydrogen bonds and other interactions such as van der Waals, Pi-Pi interactions and other polar interactions (as shown in Fig. 1), thus indicating its potential importance in IAV inhibition. The results of the protein-ligand docking analysis identified diosmin as the highest-scoring ligand, along with orientin and fisetin, as the three flavonoids exhibiting the strongest binding to IAV proteins. Consequently, these flavonoids were selected to undergo further in vitro cytotoxicity and antiviral assays against H1N1 of IAV.

Cytotoxicity assay of flavonoids in A549 cells

Diosmin, orientin and fisetin were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against A549 cells using the MTS reagent. Table 3 shows the CC50 and MNTD values of diosmin, fisetin, and orientin against A549 cells. According to the findings, all tested flavonoids exhibited no significant cytotoxicity on A549 cells, even after 48 h of incubation at concentrations of up to 5000 μM for diosmin and 1000 μM for both fisetin and orientin (Fig. 2). The CC50 and MNTD values of diosmin were determined to be 11320.23 ± 2.29 μM and 1710.46 ± 2.11 μM, respectively, which were higher than those of both orientin and fisetin. Additionally, the CC50 values of orientin and fisetin were found to be approximately the same, at 1043.05 ± 3.41 μM and 1190.30 ± 3.52 μM, respectively. Moreover, the MNTD values for orientin and fisetin were recorded as 180.31 ± 0.92 μM and 121.89 ± 0.99 μM, respectively. Building on these findings, a standardized highest concentration of 25 μM for diosmin, fisetin, and orientin was chosen for the primary antiviral screening. This concentration corresponds with previous in vitro studies investigating the biological effects of flavonoids on human cells27,28,29 and it remains below their MNTD values, thus ensuring the safety of A549 cells in this study.

Cytotoxic effects of (a) diosmin, (b) orientin, and (c) fisetin in A549 cells. Serial dilutions of flavonoids were prepared in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, and A549 cells were exposed to these diluted flavonoids for a duration of 72 h. The cytotoxicity of each flavonoid was assessed using the MTS assay, and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The presented data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with error bars indicating the range of values obtained from three independent experiments.

Primary antiviral screening of flavonoids against IAV

Using non-cytotoxic concentrations of flavonoids, ranging up to 25 μM, we conducted an in vitro primary screening to assess the potential antiviral activity of diosmin, orientin and fisetin. The viral H1N1 RNA copy number was quantified using qRT-PCR prior to the screening process. The concentration of flavonoids that resulted in a half-maximal inhibition of the viral RNA copy number (IC50) was utilized to rank the inhibition activity of the flavonoids (Table 4). Among the tested flavonoids, diosmin displayed the highest inhibition activity, exhibiting an IC50 value of 2.91 ± 3.22 μM, followed by orientin and fisetin with IC50 values of 8.98 ± 2.03 μM and 142.60 ± 6.19 μM respectively. Based on Fig. 3, diosmin and orientin exhibited significant inhibitory activity across all tested concentrations, leading to a lower percentage of IAV RNA copy number compared to the infected A549 cells without treatment (virus control). In contrast, fisetin showed significant inhibition activity only at its highest concentration, with a lower percentage of inhibition compared to diosmin and orientin. Moreover, exposure to diosmin at concentrations of 6.25, 12.5, and 25 μM led to a decrease in viral RNA levels to less than 20%, aligning with the performance of oseltamivir, the positive control. Given diosmin’s highest inhibitory activity among the flavonoids tested and its level of inhibition on par with oseltamivir, diosmin was selected for further assessment using specific antiviral assays.

The percentage of H1N1 RNA copy number from virus control (infected A549 cells without treatment), fisetin, orientin, diosmin and oseltamivir (positive control) treatment groups obtained from primary antiviral screening. The data is presented as mean ± SEM, with error bars indicating the range of values observed in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 indicate a significant difference compared to the virus control, while “ns” represents a non-significant difference, analyzed by the t-test.

Diosmin displayed prophylactic and antiviral activity at the early and later stages of viral replication

Next, diosmin was subjected to a time-of-addition antiviral assay to assess its effects on various stages of viral replication based on the addition of treatment at different time points during infection. The results of the time-of-addition assay are presented in Fig. 4, showcasing the percentage of H1N1 RNA copy numbers for both the virus control (infected A549 cells without treatment) and infected A549 cells treated with 25 μM of diosmin across different time intervals. The addition of diosmin at each time point led to a significant reduction (p < 0.0001) in the percentage of viral RNA copy numbers. Among the time points examined, the highest viral inhibition was observed at − 2 h post-infection (hpi), followed by 0 hpi and 2 hpi. After 4 hpi, a notable increasing trend in viral RNA copy numbers was observed, indicating a diminishing antiviral activity of diosmin over time or an escalation in viral replication rates (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). It can be inferred that diosmin displays antiviral properties at the early (0 hpi) and later (2 hpi) stages of viral replication, while also exhibiting a prophylactic activity (− 2 hpi) against the virus.

The percentage of H1N1 RNA copy number from virus control (infected A549 cells without treatment) and diosmin-treated samples obtained from the time-of-addition assay. The data is presented as mean ± SEM, with error bars indicating the range of values observed in three independent experiments. “hpi” represents hour/hours post-infection, while ****p < 0.0001 indicates a significant difference compared to virus control, analyzed by the t-test.

Induction of host antiviral genes by diosmin

Building on the initial findings of the prophylactic potential of diosmin, as observed in the time-of-addition assay (treatment of diosmin at − 2 hpi), our research aimed to investigate the cellular changes that occur post-treatment with diosmin before an infection takes place. We hypothesized that diosmin might induce the expression of host antiviral genes prior to an infection, thereby enhancing immune defenses against the virus. This investigation focused on the impact of diosmin treatment before infection on the expression of host antiviral genes. IFN-α was used as a positive control due to its strong antiviral and immune-modulatory properties30. The selected host antiviral genes, including IFITM-1, ISG15, ISG20, Mx-A, OAS-1, RSAD2, and SHFL, have been intricately involved in the innate immune system, showcasing diverse antiviral strategies that inhibit IAV replication31,32. Figure 5 presents the relative quantification analysis of expressed genes from cells treated with diosmin and IFN-α, compared to the untreated cells (control). The results indicate that diosmin treatment enhances the expression of nearly all antiviral genes, except for RSAD2. Noteworthy fold changes were observed in ISG15 (6.774), SHFL (4.148), Mx-A (2.163), and OAS-1 (2.035), signifying their significant upregulation. These findings suggest that diosmin-mediated induction of antiviral genes may be related to the inhibition of IAV replication.

The relative quantification of expressed genes from cells treated with diosmin and IFN-α (positive control) in comparison with cell control (cells without treatment). The levels of gene expression were normalized to the cell control. β-actin was used as the reference gene. The data is presented as mean ± SEM, with error bars indicating the range of values observed in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 indicate a significant difference compared to the cell control, while “ns” represents a non-significant difference, analyzed by the t-test.

Diosmin interfered with the attachment and post-entry stages of IAV replication

The antiviral activity of flavonoids was investigated at different viral replication stages using targeted assays, including the virucidal, attachment, entry, and post-entry assays. The virucidal assay aimed to evaluate the flavonoid’s potential for directly inactivating viral infectivity. The attachment and entry assays were conducted to assess the antiviral activity of the flavonoid at the stages of IAV hemagglutinin attachment to host receptor and viral particle internalization through endocytosis. Additionally, the post-entry assay was carried out to determine the flavonoid’s antiviral activity after the entry stage, encompassing virus-host cell membrane fusion, replication and transcription of viral RNA, translation of viral proteins, and other associated steps. Three different categories of samples were involved: virus control (infected A549 cells without compound treatment), positive control (infected A549 cells treated with 10 μM of oseltamivir) and infected cells treated with diosmin at concentration of 3.123 μM, 6.25 μM, 12.5 μM and 25 μM. The data presented in Fig. 6 demonstrate that diosmin’s inhibitory activity was dose-dependent in each of the targeted assays. According to Table 5, diosmin displayed the highest inhibition activity at post-entry stage with IC50 values of 12.17 ± 1.55 μM, followed by attachment, entry and virucidal with IC50 values of 13.35 ± 2.37 μM, 39.18 ± 0.63 μM, and 41.27 ± 4.56 μM respectively. At the highest diosmin concentration, 25 μM, mild inhibitory activity was observed with a reduction of viral RNA by just under 40% during the entry assay. However, significant inhibition exceeding 40% in viral RNA reduction was evident in the virucidal, attachment, and post-entry assays. Notably, at the post-entry assay, the percentage of viral RNA copies with diosmin at 25 μM was comparable to the positive control (oseltamivir-treated samples). These results underscore the potential of diosmin to effectively inhibit virus attachment and exert antiviral effects primarily following viral entry into the host membrane, likely during viral mRNA transcription, genome replication, and protein synthesis. These findings align with data from the time-of-addition assay, demonstrating diosmin’s effectiveness in inhibiting IAV replication at 0- and 2-h post-infection.

The percentage of H1N1 RNA copy number from virus control (infected A549 cells without treatment), diosmin and oseltamivir (positive control) treatment groups obtained from (a) virucidal, (b) attachment, (c) entry and (d) post-entry assays. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 indicate a significant difference compared to the virus control.

Downregulation of IAV NS1, NP, M1 and HA proteins in infected diosmin-treated cells

To elucidate the mechanism of action through which diosmin exerts its antiviral effects, a proteomics analysis utilizing liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) was employed. Diosmin treatment was directed towards the post-entry stage of viral replication, as it showed the highest level of inhibition at this point compared to stages like attachment and entry. Both uninfected and infected A549 cells were either left untreated or treated with 25 μM diosmin, creating four distinct groups: uninfected untreated cells (CC), uninfected diosmin-treated cells (CD), infected untreated cells (VC), and infected diosmin-treated cells (D), each replicated independently three times. After 48 h, cells were harvested, and total proteins were extracted, prepared, and subjected to in-solution tryptic digestion followed by tandem mass spectrometry analysis. MetaMorpheus identified and analyzed over 1400 peptides from both the virus and the human host, revealing seven hundred and forty-four peptides with differential presence and a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 1%. Final protein identification relied on the presence of at least 1 unique peptide per protein. Using this criterion, a total of 4 differentially expressed proteins were identified from the IAV (strain A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1) database. Specifically, NS1, NP, M1, and HA proteins were identified in both the VC and D groups. The findings in Table 6 revealed a substantial reduction in all the identified IAV proteins in infected cells treated with diosmin (D) compared to VC. HA, M1, and NP exhibited a decrease of more than two-fold (log2FC values of − 1.07, − 1.32, and − 1.45, respectively), whereas NS1 displayed the most substantial reduction, surpassing a four-fold decrease (log2FC = − 2.76).

Host proteins of IAV-diosmin play roles in signal transduction, gene expression regulation, and protein metabolism

Applying the same protein identification criteria of at least 1 unique peptide per protein, a total of 266 proteins were identified by MetaMorpheus. As illustrated in Fig. 7a, the uninfected groups CC and CD presented over 170 identified proteins, with 214 and 175 proteins, respectively. In contrast, the infected groups VC and D displayed a smaller count of identified proteins, each comprising 132 proteins. Additionally, 100 proteins were consistently found in all groups, showing a similarity, while there were also differences in the proteins identified between the groups. These shared and different protein expressions could suggest similar and varying functions and interactions within the host cells of each group. Subsequently, all 266 identified proteins underwent gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis via clusterProfiler to assign their potential functions. As shown in Fig. 7b–d, the enrichment analysis highlighted the most statistically significant biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions associated with the expressed proteins. The significantly enriched biological processes were linked with protein localization and the regulation of gene expression, as demonstrated by RNA degradation and translation initiation. Additionally, the most significantly enriched cellular components included focal adhesion, cell-substrate junction, ribosome, and vesicle lumen. The analysis of molecular function revealed that the enriched proteins were involved in nucleic acid and protein binding (such as double-stranded RNA binding, cadherin binding, ubiquitin protein ligase binding, and unfolded protein binding), catalytic activity (specifically ATPase and oxidoreductase activity), and protein folding (like protein folding chaperone and unfolded protein binding). Collectively, these GO findings suggest that the host proteins affected by IAV infection and diosmin treatment likely play roles in signal transduction, the regulation of gene expression, and protein metabolism across various cellular compartments relevant to viral replication stages.

Host proteins (a) identified in the untreated cells (CC), cells treated with diosmin (CD), IAV-infected cells (VC) and IAV-infected cells treated with diosmin (D). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of 266 proteins identified in all groups; encompassing analysis of (b) biological processes, (c) cellular components, and (d) molecular functions.

Diosmin affects protein metabolism and the immune system

To obtain insights into the antiviral effect of diosmin against IAV, the differential protein expression was determined in diosmin-treated and untreated groups. In this study, 50 significant differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were determined in both VC/CC and D/VC groups, followed by visualization of the protein expression in a heat map (Fig. 8). During IAV infection, 30 downregulated DEPs and 7 upregulated DEPs were discovered in the untreated group (VC/CC). Interestingly, the diosmin-treated group (D/VC) exhibited an opposite expression pattern of the proteins. Together, these 37 DEPs were identified as potentially linked to the inhibition of influenza virus replication by diosmin. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was subsequently developed to observe the interplay between the 37 DEPs. The constructed PPI network of DEPs consisted of 29 nodes (DEPs) and 87 edges (interactions), with eight proteins identified as single nodes that do not interact with any of the other DEPs. Using the MCL algorithm, the PPI network clustering resulted in eight highly interconnected clusters, as shown in Fig. 9 and Table 7. Cluster 1 encompassed ribosomal proteins (RPLP1, RPL14, RPL22, RPS4X, RPS25, RPS15A and RPS18), RNA helicase DDX49, and scaffold protein GCN1, all associated with protein translation. Cluster 2 included proteases (PSMA7 and PSMC2), ubiquitin-protein ligase UBE2N, transport protein VCP, and protein kinase MAP3K14, linked to immune response. Cluster 3 comprised chaperonins (CCT8, CCT6A and TCP1) involved in protein folding. Cluster 4 featured transport protein IPO4 and scaffold proteins (YWHAH and YWHAQ) contributing to vesicle-mediated transport. Additionally, cluster 5 highlighted the presence of transferase GSTP1 and actin-binding proteins (FLNC and VCL) engaged in actin-related activities. Finally, clusters 6, 7 and 8 were characterized by proteins playing a role in stress response, mRNA stability, and mitochondrial redox regulation, respectively33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

PPI network of all DEPs between D and VC retrieved from STRING and visualized using Cytoscape. In this network, nodes represented DEPs, wherein the nodes in the same cluster demonstrated the same color, except nodes with grey color represented proteins that did not belong to any cluster. Edges indicated the interactions between the DEPs, with line thickness signifying the confidence level of the interactions. A thicker line indicates a greater level of confidence in predicting the interaction.

This study shows two prominent clusters in the network, cluster 1 and cluster 2, each consisting of five or more proteins within the cluster. Cluster 1, which is associated with protein translation, stands out with the highest number of proteins with nine densely interconnected proteins within the cluster: RPLP1, RPL14, RPL22, RPS4X, RPS25, RPS15A, RPS18, DDX49, and GCN1. The cluster has close interactions with three neighboring clusters: cluster 2 (immune response), cluster 3 (protein folding), and cluster 7 (mRNA stability). Meanwhile, cluster 2, linked to immune response, features five tightly connected proteins within the cluster; PSMA7, PSMC2, UBE2N, VCP, and MAP3K14. This cluster is the central hub in the network, with the highest number of interactions with other clusters. It closely interacts with five neighboring clusters: cluster 1, focusing on protein translation; cluster 3, specializing in protein folding; cluster 4, dedicated to vesicle-mediated transport; cluster 6, involved in response to stress; and cluster 8, regulating mitochondrial redox. Taken together at this point, diosmin potentially interferes with IAV by targeting essential host functions involved in regulating protein translation and immune response.

We expanded our grasp of the network cluster by conducting Reactome pathway analysis and merging the outcomes with our network cluster data. We focused on pathways enriched with a minimum of 3 significant genes, having a p-value below 0.01 and FDR under 0.05. Enriched pathways included those concerning disease (viral and influenza infections), protein metabolism (viral mRNA translation and chaperonin-mediated protein folding), the innate immune system, cell cycle checkpoints, and cellular stress response (Table 8). The pathways associated with infectious diseases, particularly those induced by the influenza virus, were notably predominant in clusters 1, 2, and 4, indicating alterations in host proteins due to IAV infection and interference by diosmin. The inhibition of IAV by diosmin also had implications on host protein metabolism, affecting processes like protein translation and folding machinery, exemplified by clusters 1 and 3. The tug-of-war between IAV and diosmin further impacted the innate immune response, cell cycle checkpoints, and cellular reactions to stimuli. Cluster 2, primarily representing immune responses, exhibited active participation in the innate immune system pathway, along with contributions from clusters 3 and 5. The involvement of clusters 2 and 4 in the cell cycle checkpoints pathway was notable. In addition, all clusters, except for clusters 3, 4, and 7, played roles in cellular stress responses. Examining the overlap between the clusters and pathways revealed that cluster 2 was extensively engaged in vital pathways related to viral infections, innate immune responses, cell cycle regulation, and responses to cellular stress, underscoring its pivotal role in anti-IAV functions.

Diosmin inhibits IAV replication by modulating the innate immune response

Given the significant presence of proteins from cluster 2 in the innate immune system pathway and the potential impact of this immune response cluster on various pathways, our interest is piqued by the mechanisms at play within the host’s innate immune system during the interaction between IAV and diosmin. To delve deeper into the anti-IAV mechanisms mediated by diosmin through the innate immune system, we performed a comprehensive analysis by mapping all proteins in the cluster network to the InnateDB database and enhancing interaction identification in STRING/Cytoscape. Nine DEPs (UBE2N, MAP3K14, PSMA7, PSMC2, HSPB1, VCP, YWHAQ, YWHAH, and GSTP1) were identified to have functional interactions with a network comprising 20 innate immune proteins from InnateDB, as depicted in Fig. 10.

Interaction between DEPs of D/VC and proteins involved in innate immune system retrieved from STRING and InnateDB, before visualized in CYTOSCAPE. The nodes represent proteins, where the nodes with turquoise color represent D/VC DEPs and the nodes with orange color represent proteins involved in innate immune system (InnateDB interactors). The lines connecting the nodes indicate the association between the proteins. The thicker the line, the higher the degree of confidence prediction of the interaction.

InnateDB interactors primarily engage with UBE2N and MAP3K14, followed by VCP, PSMA7, GSTP1, HSPB1, PSMC2, YWHAH, and YWHAQ. These interactor proteins are recognized for their roles in stimulating type I interferon production and regulating anti-inflammatory pathways, suggesting that the nine DEPs primarily operate within the same pathways in innate immunity. Specifically, UBE2N, MAP3K14, PSMA7, YWHAH, YWHAQ, and VCP are involved in promoting type I interferon, while GSTP1, HSPB1, and PSMC2 contribute to anti-inflammatory actions (Table 9).

Discussion

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a prevalent strain impacting both humans and animals, known for causing global pandemics and significant morbidity and mortality, with seasonal influenza resulting in a notable burden of severe cases and deaths each year4. While several antiviral drugs are used to treat different types of IAV, reports indicate that some strains have developed resistance to these treatments53. Flavonoids, as a potential candidate for influenza antiviral drugs, have the ability to target both viral proteins and host factors involved in virus replication. Among the flavonoids, diosmin is a promising candidate. Diosmin (diosmetin 7-O-rutinoside) was first isolated from leaves of Scrophularia nodosa L. (Scrophulariaceae) in 192554. Based on previous reports, diosmin is effective against several diseases associated with chronic inflammation such as cardiovascular disease55, cancer56 and neurodegenerative disease57. It also has medical benefits against hyperglycemia and diabetes58. Most of the bioactivities of diosmin are based on strong antioxidant effects of its free radical scavenger activity that reduce oxidative stress54. Diosmin also has a protective effect against lung and pulmonary injury induced by high oxidative stress and inflammation condition59, and these characteristics make diosmin a good candidate for treating serious influenza complications. In terms of antiviral activity, diosmin was reported to inhibit human rotavirus60 and dengue virus15 replication.

This study assessed the efficacy of diosmin and other selected flavonoids as antiviral against IAV. Diosmin was found to be the ligand with the strongest binding to the IAV proteins (NS1, HA and NA) compared to other flavonoids during in silico molecular docking screening. This docking study utilized CB-Dock2 to accurately detect protein binding cavities before proceeding with the ligand docking. The identified binding cavities on IAV proteins by CB-Dock2 were considered druggable pockets, as supported by previous studies on NS161, HA62 and NA63 proteins. It was observed that viral residues interacting with diosmin in the NS1 binding cavity are highly conserved61 and crucial for NS1 functions, particularly in anti-apoptotic signaling responses via PI3K activation (L14164 and F20165), inhibition of pre-mRNA processing through CPSF30 interaction (H16966 and K17567,68), and modulation of antiviral responses (A17169 and A20270). Moreover, diosmin was engaged with a highly conserved residue Y98 at the host receptor binding site of HA, which anchors the host cell surface receptor during viral attachment62,71. Diosmin also interacted with key HA residues for membrane fusion (A9672) and for maintaining HA stability (L7373, E7474, and Q10473). In the case of NA, diosmin was in contact with residues in both the catalytic63 (R224, E276, R292, R371, and Y406) and non-catalytic75 (S370, N372, T403, and K432) binding sites, as well as framework residues76 (I222, E227, E277, and N294) that are essential for NA activities. Furthermore, comparing our findings and previous docking studies, diosmin performed as effectively or even better than flavonoids with known anti-influenza activity13,77,78,79,80. Diosmin demonstrated stronger binding interactions with NS1 compared to baicalein77, and higher binding affinities than apigenin78 and catechin79 with the HA protein. In NA docking, diosmin outperformed kaempferol and luteolin80, while standing on par with quercetin13.

This in silico docking analysis aligns with results from in vitro antiviral screening, where diosmin emerged as the most potent inhibitor of IAV replication in A549 cells when compared to fisetin and orientin. This correlation suggests a link between the structure of flavonoids and their anti-influenza activity. Diosmin’s strong binding to IAV proteins during in silico docking may be explained by the abundance of hydroxyl groups (OH) and oxygen (O) embedded within its aglycone structure, as these groups have the potential to form hydrogen bonds with viral residues, thereby interfering with the viral replication7,81. Additionally, the positioning of hydroxyl groups in flavonoid structures plays a critical role in their antiviral efficacy82. Building on the study by Morimoto et al.83, having hydroxyl or methoxy groups at the 3′- and 4′-positions of the B ring enhances the anti-influenza properties of flavonoids, while a modified hydroxyl group at the 3-position of the C ring, as observed in flavonols, diminishes their antiviral activity. This sheds light on the reduced antiviral activity of fisetin as a flavonol, compared to flavones like diosmin and orientin, as supported by in vitro antiviral study. Furthermore, the presence of a prenyl moiety with additional hydroxyl groups enhances the binding affinity of flavonoids84. This feature is demonstrated by the rutinoside component in diosmin, leading to an increase in the number of hydrogen bonds and other interactions, potentially explaining its superior anti-influenza activity in comparison to orientin.

To delve deeper into the specific stages of IAV replication affected by diosmin, we employ a time-of-addition assay85,86 to pinpoint the best timing for drug treatment to efficiently inhibit viral replication. Based on this assay, diosmin displayed prophylactic activity against IAV. The prophylactic potential of diosmin against IAV aligns with results from Oo et al.15, wherein over 50% suppression of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) RNA was observed when cells were treated with diosmin 2 h before viral infection (− 2 h). Given the consistent results observed alongside Oo et al.15, we are intrigued by the underlying mechanisms of diosmin’s prophylactic activity against viruses and the changes occurring in the cells treated with diosmin prior to infection. In response to the inquiries, we analyzed the changes of host antiviral gene expression in A549 cells post-diosmin treatment. Our study found that diosmin enhances the expression of nearly all antiviral genes, IFITM-1, ISG15, ISG20, Mx-A, OAS-1, and SHFL, except for RSAD2. We hypothesized that the induction of these ISGs by diosmin could be a key factor contributing to its preventive effects against IAV, affecting each stage of the viral life cycle either directly or indirectly87. Interferon-induced transmembrane (IFITM) protein encoded by ISGs interferes with viral-host membrane fusion88,89, concurrently murine myxovirus resistance 1 (Mx1) protein restrains viral components in the cytoplasm, blocking the nuclear import of vRNP90. Meanwhile, host antiviral effectors including oligoadenylate synthase 1 (OAS-1), and interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) target viral genome replication, and translation stages. OAS-1 halts viral protein synthesis by destroying viral RNA in the cytoplasm91, while ISG15 covalently attaching to IAV NS1 (a process termed ISGylation) causes a loss of NS1 function92, with NS1 playing a role in selective translation of viral mRNA93. Moreover, ISG20 prevents IAV replication by interacting with the viral nucleoprotein (NP) and suppressing viral polymerase activity94, while SHFL escape host shut off mediated by PA of IAV95.

Diosmin also displayed antiviral activity at the early and later stages of IAV replication in time-of-addition assay. To confirm these findings, we conducted specific antiviral assays focusing on the early (virucidal96, attachment96, and entry97 assays) and late (post-entry assay98) stages of viral replication. Notably, diosmin was observed to interfere with the attachment and post-entry stages of IAV replication, aligning with the results of the time-of-addition assay, which showed the efficacy of diosmin in inhibiting IAV replication at 0- and 2-h post-infection. Following this, we want to understand how diosmin exerts its anti-influenza A virus effects, specifically during attachment and post-entry, and whether it involves direct interaction with viral components like viral proteins or indirect mechanisms targeting host factors. To address these, we investigate the expressions and interactions of viral and host proteins during IAV-diosmin battle using LCMS-based proteomics analysis. By examining the protein expression profiles in response to antiviral treatment during viral infection, a comprehensive understanding can be achieved regarding the underlying mechanisms driving viral pathogenicity and the specific modes of action through which antiviral agents exert their effects99. Based on proteomics analysis, treatment with diosmin that targeting the post-entry stage of viral replication, resulted in reduced levels of NS1, NP, M1, and HA proteins of IAV in the infected A549 cells. This finding is consistent with antiviral assays showing diosmin’s effectiveness against IAV by downregulating viral proteins post-treatment. However, it remains unclear whether the decrease in viral proteins is a direct interaction of diosmin or an indirect effect. Although molecular docking and the virucidal assay support the theory of direct interaction between diosmin and viral proteins, potentially binding to IAV proteins and directly inactivating viral infectivity respectively, additional specific assays are crucial to increase confidence in this theory, probably utilizing in vitro structural analyses like NMR spectroscopy100.

Rather than direct intervention, we delve into the indirect anti-influenza mechanisms of diosmin by examining host factors, given the virus’s dependency on host cellular machinery for replication. The strategic targeting of host factors in antiviral approaches presents advantages, including reducing the risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), as these factors are typically evolutionarily preserved101. Furthermore, this strategy offers potential applicability against viruses with common molecular pathways102. All 266 identified host proteins in this study likely play roles in signal transduction, the regulation of gene expression and protein metabolism, revealed by gene ontology analysis via clusterProfiler. Previous studies reveal changes in cellular signalling subsequent to influenza infection, including NF-kB103,104, PI3K/Akt105,106, MAPK107, PKC/PKR108,109, and TLR/RIG-I110 signalling cascades. These cellular signalling cascades further impact on the host regulation of gene expression and protein metabolism111,112. Of all identified proteins, there were thirty-seven significant upregulated and downregulated host proteins linked with the inhibition of IAV replication by diosmin. These significantly differential expressed proteins (DEPs) were analyzed for their protein-protein interaction (PPI) in STRING-Cytoscape platform with the integration of PANTHER, Reactome and InnateDB. The DEPs in PPI network were grouped into eight clusters, with cluster 2 linked with immune response has the most number of interactions with other clusters, suggesting immune response has a central role in the DEPs network. The Reactome pathway analysis supports the clustering findings by showing that the DEPs network was associated with innate immune system pathways. Subsequently, we mapped the DEPs into innate immunity interactions and pathways database, InnateDB, to identify specific roles of our DEPs in innate immune system. The findings revealed eight upregulated proteins - UBE2N, MAP3K14, PSMC2, HSPB1, VCP, YWHAQ, YWHAH, and GSTP1, as well as one downregulated protein, PSMA7, which have functional interactions within an innate immune protein network. Specifically, UBE2N, PSMA7, YWHAH, YWHAQ and MAP3K14 are linked to type I interferon induction, while GSTP1, HSPB1, PSMC2, and VCP contribute to anti-inflammatory effects within innate immunity.

Induction of type I interferon is highly related to the first discovered protein associating the mitochondria to antiviral type I interferon signals, MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signalling protein; previously known as IPS-1/VISA/Cardif)113,114,115. RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene-I protein or known as DDX58) and MDA5 (melanoma-differentiation-associated gene 5) pathogen recognition receptors (PRR) that detect ssRNA and dsRNA of IAV in cytoplasm116, interact with MAVS in retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLR) signalling, through caspase-recruitment domains (CARDs) interaction117. In our study, at least four proteins are potentially involved in this RLR signalling: UBE2N, PSMA7, YWHAH and YWHAQ. UBE2N and PSMA7 are associated with the regulation of MAVS by ubiquitination, whereas in this study, upregulation of UBE2N and downregulation of PSMA7 were observed in IAV-infected cells after treatment of diosmin. It has been reported that UBE2N, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, is required for RIG-I-mediated MAVS aggregation, triggering IFN-α/β production in response to virus infection45. Conversely, Jia et al.46 discovered that overexpression of the proteasome PSMA7 led to MAVS ubiquitination, indicating PSMA7-mediated proteasomal degradation of MAVS, significantly inhibiting IFN-β promoter activity. Decreasing PSMA7 expression using small interference RNA enhanced virus-induced type I interferon production, subsequently reducing virus replication. Next, YWHAH and YWHAQ are both 14-3-3 proteins with tightly close interactions and activities that serve as an important regulator in the type I IFN induction pathway47. A study by Lin et al.47 indicated the vital role of YWHAH as a crucial accessory protein in MDA5-dependent type I interferon induction. When YWHAH was knocked down, it impaired MDA5 activation, resulting in a decrease in MDA5-dependent IFN-β promoter activities and the level of IFN-β mRNA expression. Similarly, Li et al.48 showcased that YWHAQ significantly boosted IFN-β promoter activity and had the capacity to inhibit H5N1 replication. Apart from cytoplasm, IAV genome is also being detected in the endosome by toll-like receptors (TLR) such as TLR3118, TLR7119,120, TLR8121 and TLR9122. In the case of our study, MAP3K14 (also known as NIK) may induce type I interferon production through TLR. Wang et al.36 discovered that MAP3K14 serves as a kinase upstream in the IKKα-mediated activation of IRF7, playing a pivotal role in the TLR7-MyD88-TRAF6-IKKα-mediated induction of IFN-α. Knocking down MAP3K14 inhibited the activation of the IFN-α4 promoter mediated by TLR7, TRAF6, or MyD88. Moreover, the activation of the IFN-α4 promoter through TRAF6 was notably diminished in MAP3K14-deficient cells.

While type I interferon is crucial for the antiviral defense, excessive production of IFN-α/β leading to an uncontrolled cytokine storm with pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-18 could exacerbate inflammation and harm the host123. Antiviral treatments that can effectively decrease both viral replication and lung inflammation would be highly valuable in this context124. In our study, four proteins were observed to be upregulated: GSTP1, HSPB1, PSMC2, and VCP, potentially playing roles in the anti-inflammatory response. GSTP1, for instance, is known to regulate TNF-α-induced signalling by engaging in ligand-binding interactions with TRAF249, with reported inhibitory effects on acute inflammation in vitro and in vivo125. HSPB1 has been shown by Ogbodo et al.50 to be capable of activating cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10, thereby modulating the inflammatory response. Study by Bouwmeester et al.51 highlighted the involvement of PSMC2 in the TNF-α/NF-κB signal transduction pathway. Meanwhile, inhibiting VCP can delay the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and accentuate lysosomal damage126. Our proteomics results suggest that the anti-influenza mechanism of diosmin may involve both RLR and TLR pathways, since the IAV genome can be presence in both cytoplasmic and endosome for the viral recognition that induces antiviral signalling. Furthermore, this potential antiviral effect is in balance with the anti-inflammatory effect that protects the host from damage by the immune system.

In conclusion, by integrating in silico, in vitro, and proteomics analyses in this study, we suggest that diosmin’s prophylactic and antiviral activity against influenza A virus could be attributed to its interactions with viral components such as NS1 and HA, along with its impact on host factors by regulating proteins involved in RLR and TLR-related host defense and anti-inflammatory pathways. Further detailed evaluations of diosmin’s anti-IAV effects and the pathways involved are needed, potentially in an in vivo setting, to strengthen the reliability and confidence of the findings. These initial results underscore the importance of continued research in exploring the full potential of diosmin as a therapeutic agent against influenza viruses.

Methods

Ligand and protein structure preparation

The molecular docking analysis utilized 3D crystal structures of IAV structural and non-structural proteins, hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA) and non-structural protein 1 (NS1), which were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) (with PDB ID of 4EDB, 3NSS and 3RVC, respectively). These viral proteins were selected due to their role in escaping the host’s immunity87 and escalating the pathogenicity20,21,127,128. A flavonoid compound library consists of 260 compounds provided by Selleckchem (USA), with catalog number of L7700, was selected for the screening process and the list was filtered according to several criteria, such as (i) the flavonoids must have at least one rotatable bond, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and four hydrogen bond donors; (ii) Flavonoids have been reported to possess known antiviral potential against various viruses, but their antiviral activity against IAV has not been previously documented. The keywords ‘viruses’, or ‘influenza virus’, or ‘influenza A virus’, or ‘IAV’, or ‘flu virus’ in association with the name of filtered flavonoids such as ‘rutin’, or ‘kaempferol’ or ‘quercetin’ were used in the database search against Web of Science, PubMed and Google Scholar. The flavonoids filtering and shortlisting protocol is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2. The ligands examined in this study include astilbin, calycosin 7-O-glucoside, diosmin, engeletin, fisetin, orientin, pectolinarin, quercetagetin, schaftoside, and trilobatin (Supplementary Table 1). Ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database and both the proteins and ligands were prepared in Discovery Studio. The software was used to remove water molecules and add polar hydrogen before undergoing docking via CB-Dock2 webserver (https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/php/index.php) 129.

Molecular docking

CB-Dock2 utilizes a protein-surface-curvature-based cavity detection approach named CurPocket to guide blind molecular docking with AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2). After prepared proteins and ligands input were submitted, CB-Dock checked the input files and converted them to pdbqt formatted files using OpenBabel and MGLTools130. Subsequently, CB-Dock predicted the cavities of the protein and calculated the centers and sizes of the cavity. The detected major cavity volume and center point axis of the proteins were NS1 (PDB ID: 3RVC, cavity volume: 285 Å3, center_x: − 5, center_y: 2, center_z: − 10), HA (PDB ID: 4EDB, cavity volume 1069 Å3, center_x: − 2, center_y: 58, center_z: 44) and NA (PDB ID: 3NSS, cavity volume: 415 Å3, center_x: 11, center_y: 16, center_z: 60). Meanwhile, the cavity size for each protein along the x, y, and z axes was calculated as 31. The cavity information, together with the pdbqt files, was submitted to AutoDock Vina for docking. The results were visualized and analyzed after the computation of the fifth round using interactive NGL Viewers and Discovery Studio Visualization tools to explore the 3D structures, 2D sequences, and comprehensive information about binding sites, binding scores, contact residues, docking center, and cavity volume. CBDock2 reached about 70% similarity in the top-ranking positions and was within a 2 Å root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from X-ray crystallography.

Cell and virus

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were purchased from iCell Bioscience Inc (Shanghai, China). Carcinomic human alveolar epithelial (A549) cells were a kind gift from Dr. Lim Yat Yuen (Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya). MDCK cells and A549 cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The IAV H1N1 strain A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (ATCC, USA) was propagated in MDCK cells supplemented with maintaining medium (medium with 2% FBS and 1 mM l-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin from Sigma-Aldrich). After propagation, the virus supernatant (virus stock) was aliquoted, and stored at − 80 °C.

Virus titer determination

The virus stock was titrated in MDCK monolayer cells through the foci forming unit assay (FFUA). MDCK cells were seeded into a 24-well tissue culture plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. On the following day, the virus stock underwent ten-fold serial dilution using maintaining medium. The previous culture medium was removed from the wells, and the cells were then infected with the diluted viruses and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, the overlay medium (composed of maintaining medium and 1% high viscosity carboxymethyl cellulose at a ratio of 1:1) was added, and the plates were further incubated for 48 h in the same condition. After incubation, the overlay medium was discarded, and the cells were washed with PBS. The cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 1 h, washed again with PBS, and incubated with the primary antibody against H1N1, which was diluted in 4% skim milk at a ratio of 1:500, for 1.5 h at 37 °C. After washing the primary antibody with PBS, the cells were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in skim milk at a ratio of 1:500 for 1 h at 37 °C. The secondary antibody was then washed away, and the DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) substrate (Thermo Fisher, UK) was added to each well in the dark. Subsequently, the foci in each well were quantified, and the titer of the virus was assessed in terms of foci forming units per microliter (FFU/mL).

Compounds

Diosmin, fisetin, orientin and oseltamivir phosphate (was used as a positive control) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA) with a purity level exceeding 98%. Each compound was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare a stock solution of 50 mM and stored at a temperature of − 20 °C until use. To obtain a working solution, the stock solution underwent dilution to the appropriate concentration in maintaining medium. Filtration through a 0.2 mm pore size syringe filter was performed to ensure the sterility of the solution.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the compound against A549 cells was assessed using MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) assay kit (Promega, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay relies on the conversion of MTS to a formazan product by NADPH-dependent dehydrogenase enzymes present in viable cells, as previously described131. The resulting formazan product is then quantified by measuring the absorbance at 490–500 nm132. By determining the concentration of each flavonoid that causes a 50% reduction of cell viability (half maximal cytotoxic concentration; CC50) and the dose at which 90% of the cells remain viable (maximum non-toxic dose; MNTD), the cytotoxicity of flavonoids against A549 cells can be assessed. A monolayer of cells was grown in a 96-well cell culture plate, followed by the addition of the compound in maintaining medium at varying concentrations in triplicate. After 3 days incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, the MTS reagent was added, and the cells were further incubated for 2 h at the same condition. The absorbance of each well was measured at a 490 nm wavelength using an Infinite 200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland). The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) and the maximum non-toxic dose (MNTD) for the compound were determined by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism 9 software (USA). Cell viability was compared to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated controls.

Primary antiviral screening

The assay protocol was adapted and conducted based on the methodology introduced by Moghaddam et al.133, where this screening assay assesses compounds antiviral potentials at pre- and post-virus adsorption stages. A confluent monolayer of A549 cells underwent cultivation in a 24-well plate and was exposed to increasing concentrations of the compound. Simultaneously, the cells were infected with H1N1 virus at a MOI of 0.1 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. In this antiviral assay, a concentration of 10 μM of oseltamivir was employed as the positive control134. After the incubation period, the supernatants were removed, and the newly prepared compound was added to the respective wells at the same concentrations as previously. The plate underwent incubation for 2 days, and the supernatants were harvested for virus yield evaluation using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) method.

Virus yield evaluation using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Following the manufacturer’s protocol, viral RNA from the antiviral assay supernatant was extracted using QIAamp® Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The extracted viral RNA was then amplified and quantified through quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Using Quantstudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) with SensiFAST™ SYBR® Hi-ROX One-Step Kit (Bioline Meridian Bioscience, UK) and serially diluted standards of known H1N1 concentrations, qRT-PCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol; 45 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 2 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 5 s. Melting curve analysis was used to verify the amplified cDNA products. The primers specific to the NA gene of H1N1 were designed using Primer-BLAST (NCBI) as follows: NA-F (5′-GCA GCT GTG GTC CAG TGT AT-3′) and NA-R (5′-GCC ACA ACA TCT TGC CTC AC-3′).

Time-of-addition assay

This assay was modified and performed according to Albeshri et al.86. A dilution of virus inoculum (MOI 0.1) was prepared, followed by the preparation of a single concentration of 25 μM (the highest concentration of compound, but below the MNTD value). For the pre-treatment assay, the A549 cell monolayers were treated with the compound for 1 and 2 h before infection with the virus. In the co-treatment assay, at 0 h, both the virus inoculum and the compounds (including positive control: 10 μM oseltamivir) were introduced together. The virus inoculum was also administered at the same time in the pre-treatment, post-treatment and positive control wells. For the post-treatment assay, the compound was added at 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after infection. The treated plate was then incubated at 37 °C ± 5% CO2 for 48 h. After 48 h, the supernatant from each well was harvested for virus yield evaluation using qRT-PCR method.

Host antiviral gene expression study using qRT-PCR

A549 cells were cultured as a monolayer in a 24-well plate and treated with diosmin (100 μM) and interferon α (IFN-α) at a concentration of 100 mU/mL (positive control). The cells were then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After incubation, RNA was extracted from the cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germany) and subsequently synthesized into cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). The qRT-PCR was performed on the cDNA using the Luna Universal qRT-PCR kit (New England Biolabs) in the Quantstudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). Supplementary Table 2 presents the primers, previously described by Tsuji et al.135, that were used for targeting the reference gene β-actin (ACTB) as well as host antiviral genes including interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM-1), interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), interferon-stimulated gene 20 (ISG20), myxovirus resistance protein A (Mx-A), 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS-1), radical S-adenosyl methionine domain-containing 2 (RSAD2), and shiftless antiviral inhibitor of ribosomal frameshifting (SHFL). All primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (USA). We adopted the relative quantification (RQ) method developed by Livak and Schmittgen136 to calculate the fold change of each sample relative to the calibrator (cell control). A minimum two-fold change in RQ is considered significant.

Virucidal assay

This assay was modified and performed according to Garozzo et al.96. To assess the virucidal activity, a dilution of the virus inoculum (MOI = 1) and a serial dilution of the compound were prepared in maintaining medium. Next, a 1:1 mixture of the virus inoculum and each compound concentration (including positive control: 10 μM oseltamivir) was prepared in a 1.5 mL tube, which was then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, A549 cells were infected with the diluted treated viral suspension (dilution to MOI 0.1) to exclude any potential effects of the compounds on virus adsorption. Following this step, the plate was incubated at 37 °C ± 5% CO2 for 1 h. After the incubation period, the cells were washed once with sterile PBS before adding the maintaining medium. The plate was further incubated for 48 h at 37 °C ± 5% CO2. After 48 h, the supernatant from each well was collected for virus yield evaluation using qRT-PCR method.

Attachment assay

This assay was modified and performed according to Garozzo et al.96. For the attachment assay, a dilution of the virus inoculum (MOI 0.1) was prepared and treated with 10 μM oseltamivir as positive control and increasing concentrations of the compound in separate 1.5 mL tubes at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the virus-compound mixtures were incubated on ice for 15 min. Simultaneously, A549 monolayer cells were pre-chilled at 4 °C for 1 h. After that, the virus-compound mixtures were added to the A549 cells and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h to allow virus attachment137. After the incubation period, the treatment was removed from each well, and maintaining medium were added before incubating the plate for 48 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 48 h, the supernatant from each well was collected to evaluate virus yield using qRT-PCR method.

Entry assay

This assay was modified and performed according to Hsieh et al.97. The entry assay commenced by preparing a dilution of the virus inoculum (MOI 0.1), alongside serial dilutions of the compound in maintaining medium. Following pre-chilling of the virus inoculum and A549 monolayer cells at 4 °C for 15 min and 1 h, respectively, the growth medium (medium with 10% FBS) was replaced with the virus inoculum in each well, allowing for a 1-h incubation at 4 °C to facilitate virus attachment137. Subsequently, the virus inoculum was removed, and the corresponding serially diluted compound and 10 μM oseltamivir was added to each well for a 1-h incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to promote virus entry137. After this period, cells were gently washed with sterile PBS and treated with citrate buffer (pH 3) to neutralize absorbed but non-internalized viruses. After immediate removal of citrate buffer, a further wash with sterile PBS was performed, followed by the addition of maintaining medium to the wells. Then, the plate was incubated for 48 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Finally, supernatant from each well was collected for virus yield evaluation using qRT-PCR method.

Post-entry assay

This assay was modified and performed according to An et al.98. The post-entry assay started by preparing a dilution of the virus inoculum with an MOI of 0.1, alongside serial dilutions of the compound in maintaining medium. Oseltamivir at a concentration of 10 μM was used as positive control. The growth medium was removed from the wells, and the newly prepared virus inoculum was added to each well before incubating at 37 °C ± 5% CO2 for 1 h. Following the incubation period, the virus inoculum was removed from the wells, and the serially diluted compound was added to each well, followed by further incubation at 37 °C ± 5% CO2 for 48 h. After the 48-h incubation, the supernatant from each well was collected for evaluating virus yield using qRT-PCR method.

Diosmin treatment for proteomics analysis

A monolayer of A549 cells was cultured in a 24-well plate. The cells are either infected or uninfected, and treated with diosmin or untreated, creating four distinct groups: uninfected untreated cells (CC), uninfected diosmin-treated cells (CD), infected untreated cells (VC), and infected diosmin-treated cells (D). For VC and D groups, the cells were infected with H1N1 virus at a MOI of 0.1 and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. Following the incubation period, the supernatants were removed from each well. At this point, CD and D groups were exposed to maintaining medium supplemented with 25 μM diosmin, whereas untreated groups VC and CC received the maintaining medium without diosmin. The plate was then incubated for 2 days, and subsequently, all the groups were subjected to protein extraction and lysis using ice-cold Triton X-100 (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) supplemented with EDTA-free Halt™ protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). The experiment was conducted in three biological replicates.

In-solution digestion and cleanup

Each sample, containing 100 μg of protein lysate, was processed using in-solution digestion. The procedure involved adding 25 μL of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) (BioBasic Inc., Ontario, Canada), 25 μL of tetrafluoroethylene (TFE) (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), and 1 μL of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (BioBasic Inc., Ontario, Canada) to the protein mix. After a vortex and heat treatment at 60 °C for an hour, the sample was cooled and 4 μL of 200 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was introduced, and the mixture incubated in the dark at room temperature. Following this, 1 uL of DTT was added, mixed, and incubated in the dark to deactivate excess IAM. Dilution steps with MilliQ water and ABC were carried out before adding 1 μL of MS Grade Pierce Trypsin Protease (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and incubating at 37 °C for 18 h. The trypsin reaction was stopped with 1 μL of formic acid. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the sample underwent desalting using the Pierce C-18 Spin Columns (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and subsequent drying was achieved using the Savant DNA 120 SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA).

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) analysis

After desalting and drying, the peptide samples were dissolved in 20 µL of 0.1% formic acid and subjected to analysis using nano-ESI-QTOF (Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF LC/MS) with an Agilent Large Capacity Chip (G4240-62010 300Å-C18) previously equilibrated with 0.1% formic acid (solution A). Injection of a 10 µL peptide sample initiated elution from the column at a flow rate of 500 nL/min, with a gradient elution of 5–70% of solution B (acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid) over 60 min. Positive polarity was maintained on the QTOF system with capillary and fragmenter voltages adjusted to 1900 V and 360 V, respectively. The drying gas flowed at 5.0 L/min and 325 °C through the column. Spectra were acquired using auto MS/MS mode within mass ranges of 110–3000 m/z for MS scan and 50–3000 m/z for MS/MS scan.

Label-free protein quantification and identification

Following this, the spectral files were analyzed using default parameters of MetaMorpheus138 software version 1.0.5 (Lloyd M. Smith Group, WI, USA). This software utilized an upgraded version of Morpheus139 for protein identification and FlashLFQ140 for protein quantification. We began by uploading .raw files and a FASTA file with the UniProt reference proteomes of influenza A virus strain A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) and Homo sapiens into MetaMorpheus. Each file had a single protein sequence per gene. We then calibrated the system for each MS run and searched for post-translational modifications (PTMs) like common biological changes, artifacts, and metal modifications using the PTM discovery tool. Our identification and quantification process allowed for up to two missed cleavages, two modifications per peptide, and required peptides to be at least 7 amino acids long. Specific modifications like carbamidomethylation for cysteine and selenocysteine were fixed, while methionine oxidation was a variable change. All protein sequences obtained from the searched databases were reversed to create the decoy database for calculating the false discovery rate (FDR). Valid peptide-spectrum matches had an FDR-adjusted p-value (known as q-value) of less than 0.01 and a minimum MetaMorpheus score of 5. Quantification was carried out with matching between runs, and results were normalized by FlashLFQ.

Differential protein expression, functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction analyses

Based on MetaMorpheus data, proteins identified with less than one unique peptide were excluded, along with proteins that matched peptides in the decoy database. Next. the total count of identified host proteins was visualized using the web-based tool InteractiVenn (https://www.interactivenn.net/). To elucidate the potential functions of identified host proteins, we utilized the clusterProfiler141 package for conducting functional enrichment analyses on Gene Ontology (GO). The three GO categories biological process, and cellular component, and molecular function were analyzed using the gseGO functions within the clusterProfiler package. Significantly enriched ontologies were identified with an adjusted p-value < 0.05. Additional parameters, such as a minimum number of genes in the set (minGSSize) = 3, a maximum number of genes in the set (maxGSSize) = 800, and the p-adjusted Method = Bonferroni, were also considered in this study. The proteins were then mapped to Reactome142 (https://reactome.org/) pathways, undergoing an overrepresentation test with an FDR < 0.05 threshold to select enriched Reactome pathways. Following that, the relative ratio of each protein (fold change represented as log2) between the two conditions (VC/CC, CD/CC, and D/VC) was assessed for reproducibility by analyzing the p-value (or –log10 p-value) based on the protocol outlined by Aguilan et al.143. Proteins exceeding the thresholds of p < 0.05 (or − log10 p > 1.3) and log2FC ≥ 1.0 or ≤ − 1.0 were identified as significantly differentially expressed proteins (DEPs)144. DEPs were visualized through VolcaNoseR145 (https://huygens.science.uva.nl/VolcaNoseR/) for the volcano plot and GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) for the heatmap. Subsequently, these DEPs were categorized into PANTHER146 (https://www.pantherdb.org/) protein classes and protein-protein interactions (PPIs) were retrieved from STRING database147 (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) (https://string-db.org/) with the confidence score of 0.40. The PPI network was further clustered to detect highly connected proteins within the network by utilizing Markov Clustering (MCL) algorithm148 at inflation value of 4.0 using a plugin (clusterMaker) in Cytoscape149. To investigate the network’s role in innate immunity, InnateDB150 (https://www.innatedb.com/) pathways analysis was conducted and visualized using the Cytoscape platform.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The half maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50), maximum non-toxic dose (MNTD) and half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of flavonoids in A549 cells were determined using non-linear regression curve fitting and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All CC50, MNTD and IC50 values were calculated as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from triplicate assays conducted in three independent experiments. Groups were considered statistically significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are accessible from the corresponding authors upon a reasonable request.

References

Vaidya, B. et al. Effectiveness of periodic treatment of quercetin against influenza A virus H1N1 through modulation of protein expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 4416–4425. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00148 (2016).

Spreeuwenberg, P., Kroneman, M. & Paget, J. Reassessing the global mortality burden of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 2561–2567. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy191 (2018).

Eccleston-Turner, M., Phelan, A. & Katz, R. Preparing for the next pandemic—The WHO’s global influenza strategy. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2192–2194. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1905224 (2019).

Iuliano, A. D. et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: A modelling study. Lancet 391, 1285–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33293-2 (2018).

James, S. H. & Whitley, R. J. in Infectious Diseases. 4th edn (eds Jonathan Cohen, William G. Powderly, & Steven M. Opal) 1465–1471.e1461 (Elsevier, 2017).

Principi, N. et al. Drugs for influenza treatment: Is there significant news? Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2019.00109 (2019).

Badshah, S. L. et al. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 140, 111596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111596 (2021).

Xu, X., Miao, J., Shao, Q., Gao, Y. & Hong, L. Apigenin suppresses influenza A virus-induced RIG-I activation and viral replication. J. Med. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26403 (2020).

Sithisarn, P., Michaelis, M., Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. & Cinatl, J. Differential antiviral and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of the flavonoids biochanin A and baicalein in H5N1 influenza A virus-infected cells. Antiviral Res. 97, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.004 (2013).

Song, J.-M., Lee, K.-H. & Seong, B.-L. Antiviral effect of catechins in green tea on influenza virus. Antiviral Res. 68, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.010 (2005).

Zhang, R. et al. Kaempferol ameliorates H9N2 swine influenza virus-induced acute lung injury by inactivation of TLR4/MyD88-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 89, 660–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.081 (2017).

Yan, H. et al. Luteolin decreases the yield of influenza A virus in vitro by interfering with the coat protein I complex expression. J. Nat. Med. 73, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-019-01287-7 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Computational screen and experimental validation of anti-influenza effects of quercetin and chlorogenic acid from traditional Chinese medicine. Sci. Rep. 6, 19095. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19095 (2016).

Bae, E.-A., Han, M. J., Lee, M. & Kim, D.-H. In vitro inhibitory effect of some flavonoids on rotavirus infectivity. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 23, 1122–1124 (2000).

Oo, A., Aziz, F-Z., Hassandarvish, P., Azman, A-S., Khairat, J-E., Tiong, V., Zandi, K., AbuBakar, S. Diosmin: A potential entry inhibitor of dengue virus (2019).

Lo, C. W., Pi, C. C., Chen, Y. T. & Chen, H. W. Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek extract inhibits influenza a virus by targeting viral attachment, penetration, assembly, and release. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 584973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.584973 (2020).

Hanada, A. et al. Influenza virus entry and replication inhibited by 8-prenylnaringenin from Citrullus lanatus var. citroides (wild watermelon). Food Sci. Nutr. 10, 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2725 (2022).

Jackson, D., Hossain, M. J., Hickman, D., Perez, D. R. & Lamb, R. A. A new influenza virus virulence determinant: The NS1 protein four C-terminal residues modulate pathogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 4381–4386 (2008).

Noah, D. L. & Krug, R. M. Influenza virus virulence and its molecular determinants. Adv. Virus Res. 65, 121–145 (2005).

Böttcher-Friebertshäuser, E., Garten, W., Matrosovich, M. & Klenk, H. D. in Influenza Pathogenesis and Control (eds Richard W. Compans & Michael B. A. Oldstone) 3–34 (Springer International Publishing, 2014).

Goto, H., Wells, K., Takada, A. & Kawaoka, Y. Plasminogen-binding activity of neuraminidase determines the pathogenicity of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 75, 9297–9301 (2001).

Fernandez-Sesma, A. et al. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J. Virol. 80, 6295–6304. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02381-05 (2006).

Xia, C. et al. Hemagglutinin of influenza A virus antagonizes type I interferon (IFN) responses by inducing degradation of type I IFN receptor 1. J. Virol. 90, 2403–2417. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02749-15 (2016).

Peacock, T. et al. Antigenic mapping of an H9N2 avian influenza virus reveals two discrete antigenic sites and a novel mechanism of immune escape. Sci. Rep. 6, 18745. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18745 (2016).

Hervé, P. L., Lorin, V., Jouvion, G., Da Costa, B. & Escriou, N. Addition of N-glycosylation sites on the globular head of the H5 hemagglutinin induces the escape of highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 viruses from vaccine-induced immunity. Virology 486, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.033 (2015).

Bar-On, Y., Seidel, E., Tsukerman, P., Mandelboim, M. & Mandelboim, O. Influenza virus uses its neuraminidase protein to evade the recognition of two activating NK cell receptors. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu094 (2014).

Deng, J. et al. Diosmin mitigates high glucose-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress through PI3K/AKT pathway in HK-2 cells. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 22, 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-022-03597-y (2022).

Funakoshi-Tago, M., Nakamura, K., Tago, K., Mashino, T. & Kasahara, T. Anti-inflammatory activity of structurally related flavonoids, Apigenin Luteolin and Fisetin. Int. Immunopharmacol. 11, 1150–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2011.03.012 (2011).

Khalil, H. E., Ibrahim, H.-I.M., Ahmed, E. A., Emeka, P. M. & Alhaider, I. A. Orientin, a bio-flavonoid from Trigonella hamosa L., regulates COX-2/PGE-2 in A549 cell lines via miR-26b and miR-146a. Pharmaceuticals 15(2), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020154 (2022).

Matos, A. D. R. et al. Antiviral potential of human IFN-α subtypes against influenza A H3N2 infection in human lung explants reveals subtype-specific activities. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 8, 1763–1776. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2019.1698271 (2019).

Nakayama, M. et al. Quantitative proteomics of differentiated primary bronchial epithelial cells from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and control identifies potential novel host factors post-influenza A virus infection. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.957830 (2023).

Zhou, A., Dong, X., Liu, M. & Tang, B. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis identifies novel antiviral factors against influenza A virus infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 632798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.632798 (2021).

Ishii, K. et al. Characteristics and clustering of human ribosomal protein genes. BMC Genom. 7, 1–16 (2006).

Müller, M. B. D., Kasturi, P., Jayaraj, G. G. & Ulrich Hartl, F. Mechanisms of readthrough mitigation reveal principles of GCN1-mediated translational quality control. Cell 186(15), 3227–3244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.035 (2023).