Abstract

Constructing damage constitutive model for cracked rock masses can reveal the mechanisms by which cracks influence the mechanical behavior of rock masses, providing a more scientific theoretical basis for engineering design. Damage constitutive equations for T-shaped cracked rocks were constructed based on different models in this study. Uniaxial and triaxial compression tests were conducted on rock specimens with T-shaped cracks at different angles. The applicability of the constructed constitutive model to T-shaped cracked rock and the relationship between model parameters and the angles of T-shaped cracks were investigated. The experimental data were compared and verified with the theoretical value of the power function distribution model. The results indicate that the peak strength of the specimens increases with rising confining pressure when the crack angle was identical. When the primary crack angle was 0°, parameter m decreases as the angle between the primary and secondary cracks increases, while parameter ε0 increases with the same angle. When the primary crack angle was 45° or 90°, the trend was opposite to that observed at 0°. The power function distribution model was more suitable for T-shaped cracked rock. The verification results prove the rationality and correctness of the power function distribution model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock masses with cracks are widely distributed in the Earth’s crust and constitute a common medium in engineering geology. The mechanical properties of cracked rock masses exhibit significant nonlinearity and anisotropy compared to intact rock masses. The deformation and failure behavior of cracked rock masses directly impacts the stability and safety of engineering projects1. Therefore, the damage constitutive model of cracked rock masses can be studied to characterize their mechanical behavior, predict deformation and failure processes, and provide a theoretical basis for the safety evaluation and optimized design of tunnels, slopes, dams, and other engineering projects2,3,4.

The existence of cracks has an important impact on the mechanical properties of rocks. Therefore, a large number of researchers have studied the characteristics of rock masses containing fractures5,6,7,8,9. Liu et al.10 conducted a series of uniaxial compression tests on sandstone specimens containing elliptical holes and cracks to study the strength and fracture mechanism of fractured rocks. The results indicated that the ligament angle is a critical factor affecting the strength and deformation of pre-fractured sandstone specimens. Wang et al.11 investigated the mechanical properties, acoustic emission (AE) characteristics, dynamic crack propagation, failure modes, and failure evolution of pre-fractured rock specimens with varying fissure inclination angles under uniaxial compression. The results revealed that as the fissure angle increases, the peak strength and elastic modulus first decrease and then increase. Additionally, AE exhibited distinct characteristics corresponding to changes in stress levels. Cheng et al.12 conducted compression tests to simulate the rockburst process on specimens with pre-existing, unfilled cracks in perforated circular blocks. The strength characteristics of cracked specimens, the evolution of rockburst phenomena, and the microscopic features of fracture surfaces were the focus of the study. Xue et al.13 investigated the influence of cross-jointed rock masses with different primary joint angles on the mechanical parameters of rock through mechanical testing and acoustic emission monitoring. The results indicate that the presence of cross joints significantly reduces the strength and elastic modulus of the rock mass, with smaller joint angles exerting a more adverse effect on its mechanical integrity. The methods used in the aforementioned studies of fractured rock masses typically rely on macro mechanical parameters, which struggle to accurately reflect the microstructure of fractures, their distribution characteristics, and their impact on mechanical behavior. In contrast, constructing a damage constitutive model can effectively describe the evolution of fractures and the degradation of mechanical properties, providing a comprehensive reflection of the rock mass’s mechanical behavior under complex conditions and offering a scientific basis for the precise prediction of its deformation and failure14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

The constitutive model of rock describes its mechanical behavior and deformation patterns under external forces. Numerous scholars have conducted extensive research on rock constitutive models. However, numerous damage constitutive models for rock masses have been developed with the advancement of damage mechanics4,21,22,23,24,25. The construction of damage constitutive models for cracked rock masses enables the elucidation of the mechanisms by which fractures influence the mechanical behavior of rock masses14,15,19,22,26. Kyoya et al.27 were the first to apply damage mechanics theory to the study of jointed rock masses, and a damage constitutive model based on the effective stress method was established, opening up a new perspective for research in this field. Subsequently, the study of damage constitutive models of cracked rock masses has become a hot topic in engineering and academia. Cai et al.28 proposed a constitutive model that can handle various joint distributions in rock mass. The results show that the interaction effect between joints is considered in the model using the homogenization method proposed in this study. The connection coefficient is used in the model to handle the effect of joint connectivity, which leads to a reduction in the stiffness of the system. Wang et al.29 proposed a constitutive model based on the concept of limit to predict the behavior of rock interfaces and joints. Using normalized plastic work and the limit concept, the equivalent relative displacement was obtained. The results showed that the validity of the proposed constitutive model was verified by data obtained from experimental studies on natural and artificial rock joints. Deng and Cu30 combining the theory of continuous damage mechanics with the statistical mesoscopic strength theory based on the maximum entropy distribution, proposed a statistical damage constitutive model for rocks with strain-softening characteristics. The results showed that the model was validated through conventional triaxial tests and dynamic tests on rock specimens. Afterwards, Wang et al.31 proposed a thermomechanical-mechanical-water transport coupled constitutive model to simulate the mechanical degradation of rocks after freeze-thaw cycles. Based on the internal state variable theory, the model was proposed in a generalized incremental form within the thermodynamic framework. The results showed that the model can well simulate the mechanical response of rocks after freeze-thaw cycles. Xie et al.32 considered the failure characteristics and laws of rock under strong dynamic loads and proposed the JHR damage model. Numerical simulation results show that the model can simulate the failure process of rock under blasting loads, and the simulation results are in good agreement with the experimental results. A new constitutive model was proposed and validated by Zhou et al.33, capable of simulating the cyclic behavior of rock materials under cyclic loading. The results indicated that this model effectively captures the cumulative plastic deformation, hysteresis loops, and damage of rock materials under triaxial cyclic loading. Yu et al.34 conducted triaxial compression tests on semi-penetrating jointed mudstone under different confining pressures and inclination angles, and proposed a binary constitutive model for semi-penetrating jointed mudstone samples. The results showed that the model shows the influence of inclination angle and confining pressure on the deformation characteristics of jointed mudstone. Chang et al.35 conducted biaxial compression tests on pre-cracked sandstone specimens with different ligament angles to investigate their failure modes. Additionally, a rock damage constitutive model was developed, which exhibited good agreement with experimental data during the compaction and elastic deformation stages of loading. In summary, a series of studies on the constitutive equations of cracked rock masses has been conducted by most scholars33,36,37,38,39,40,41. However, limited research has been conducted on the relationship between the damage equations of constitutive models for T-shaped cracked rock masses and their parameters with crack angles. Therefore, the damage evolution characteristics of T-shaped cracked rock masses are considered to hold significant importance for investigation.

The damage constitutive model of T-shaped fractured rock mass is established, which is of great significance to the safety and stability analysis of geotechnical engineering. Herein, damage constitutive models for T-shaped cracked rock masses based on different models were established. Uniaxial compression and triaxial compression tests were performed to examine their deformation characteristics and explore the relationship between model parameters and the angles of T-shaped cracks.

Experimental equipment and methodology

Selection of materials for T-shaped cracked rock specimens

The sand from Chanhe River in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province was selected, and the fineness modulus µf of the sand was 1.81. Before the experiment, the sand was thoroughly washed to remove impurities and then placed in an oven for 24 h at a temperature of 105 °C to dry. After drying, the sand was sieved using a 0.315 mm mesh, retaining fine sand with a particle size of 0.315 mm for specimen preparation. The cement grade used is ordinary Portland cement with P.O.32.5R (GB175-2007), and distilled water was selected as the mixing water. The parameters of the rock material are listed in Table 1.

Preparation of T-shaped cracked rock specimens

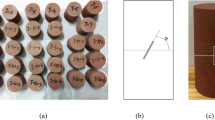

Cylindrical acrylic molds with an inner diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm were selected as the experimental molds, as shown in Fig. 1(a). After multiple trials the water-to-cement ratio was finalized as 0.45:1 and the mass ratio of cement to sand as 1:2. The prepared cement mortar was poured into the molds and then vibrated and compacted to ensure uniformity. Copper sheets measuring 0.3 mm in thickness, 20 mm in length, and 10 mm in width were then inserted into custom molds. The copper sheets were removed after standing for 8 h, and the samples were demolded 24 h later to obtain single crack and T-shaped crack specimens with varying crack inclination angles.

The prepared specimens were placed in a curing chamber maintained at a temperature of 20 °C and a humidity of 90%. The samples were cured for 28 days, they were taken out and dried naturally. According to the Standard for Engineering Rock Test Methods, a grinding machine was used to polish the two end faces of the sample so that the parallel error of the two end faces was less than 0.05 mm, the height-to-diameter ratio error was less than 0.3 mm, the end face of the sample was perpendicular to the axis with the deviation was less than 0.25°. The prepared specimens are shown in Fig. 1(b).

The specimens used in this study include intact specimens, single-crack specimens, and T-shaped crack specimens. The crack in the single-crack specimens is positioned at the center of the specimen with a length of 20 mm and angles of 0° 45° and 90° relative to the horizontal direction. The T-shaped crack specimens contain secondary cracks, with the angles between the secondary and primary cracks measured counterclockwise as 30° 60° and 90°, as shown in Fig. 2.

Test equipment

The WDT-1500 multifunctional material testing machine, jointly developed by the Geotechnical Engineering Research Institute of Xi’an University of Technology and Changchun Chaoyang Test Instrument Limited Liability Company, was used in this experiment. The equipment consists of five components: an axial loading system, a confining pressure loading system, a lateral shear system, an acoustic detection system, and a computer control and measurement system, as shown in Fig. 3. The control system adopts the DOLI fully digital servo control system imported from Germany This testing machine is a rigid servo dynamic mechanical equipment developed for testing high-strength materials such as rocks and concrete. It has the advantages of multiple functions and strong stability, providing indispensable technical support for the conduct of the test. The various indicators of the testing machine are shown in Table 2. The testing machine can record experimental parameters such as displacement, stress, strain, and time in real time. It can also generate and save the relationship curves between any two parameters.

Experimental plan

Uniaxial and triaxial compression tests were conducted in this study to determine the mechanical properties of the specimens. The loading rate was set to 0.5 mm/min, and the confining pressure in the triaxial compression test was set to 4 MPa, 8 MPa, and 12 MPa. The specific mechanical testing schemes for different combinations of crack inclination angles are presented in Table 3.

A contact force of 2 kN was set to make the sample contact the upper and lower plates of the testing machine during test. The control method adopted displacement loading and the loading rate was set to 0.5 mm/min. The uniaxial compression test is shown in Fig. 4 (a) and the triaxial compression test is shown in Fig. 4 (b).

Analysis of damage evolution characteristics in rock masses

Damage model

Damage variables

When cracks are present in the rock mass, they alter its macroscopic structural characteristics, thereby causing irreversible changes in its mechanical properties42. This study considers T-shaped cracks as an initial damage to the rock mass. The damage variable can be assumed as follows43:

where, Dφ represents the damage variable of the rock mass with T-shaped cracks under load, Eφ is the elastic modulus of the rock mass with T-shaped cracks, E0 is the elastic modulus of the intact rock mass, φ denotes the fracture inclination angle.

Establishing the damage model

According to the strain equivalence hypothesis proposed by Lemaitre44, “any strain constitutive equation established for damaged materials can be derived in the same form for undamaged materials, provided that effective stress is substituted in the equation.” Based on this, the constitutive relationship for loading-induced damage in intact rock mass is derived as follows:

where, E is the elastic modulus of the intact material, D is the damage variable under loading.

The damaged state of the fractured rock mass is considered as the first damage state, and the total damage state caused by loading is regarded as the second damage state35. The constitutive relationship for internal damage of T-shaped cracked rock material is expressed as:

Combining Eqs. (1) and (3), the constitutive relationship for rock with T-shaped cracks under loading conditions is obtained as45:

where, Ds represents the total damage variable of T-shaped fractured rock under loading45 and is calculated as follows:

Equation (5) indicates that the combined effect of fractures and loading intensifies the total damage of T-shaped cracked rock, exhibiting significant nonlinear characteristics. There is initial damage inside the rock caused by T-shaped cracks, which causes the rock to slip and dislocate under load. This coupling effect between the T-shaped cracks and the loading results in a weakening of the total damage, where DDϕ represents the coupling term in the equation.

Micro-element strength probability model of rock

Weibull distribution model

Assuming the rock microelement follows the Weibull distribution model, its probability density function is expressed as46,47:

where, m and ε0 are the parameters of the Weibull distribution.

When the rock is loaded to stress level ε, its load damage variable can be expressed as:

Power function distribution model

Assuming the microelement strength of the rock follows a power function distribution, the probability density function is given as48,49:

where, m and ε0 are the distribution parameters of the power function.

When the rock is loaded to stress level ε, its load damage variable can be expressed as:

Normal distribution model

Assuming the microelement strength of the rock follows a normal distribution, the probability density function is expressed as50:

where, σ and µ are the distribution parameters of the normal distribution.

When the rock is loaded to stress level ε, its load damage variable can be expressed as:

Constitutive equation of rock crack damage

Constitutive equation based on the Weibull distribution model

Substituting Eqs. (1) and (7) into Eq. (5) yields the total damage evolution equation for the rock with T-shaped cracks, where strain serves as the damage evolution control variable under loading conditions:

The constitutive equation for the rock mass with T-shaped cracks is obtained by substituting Eq. (12) into Eq. (4) as:

The complete stress-strain curve of the rock mass with T-shaped cracks under loading satisfies the following geometric condition at the peak stress:

(1) when \(\varepsilon ={\varepsilon _f}\), \(\sigma ={\sigma _f}\)

(2) when \(\varepsilon ={\varepsilon _f}\), \(\frac{{\partial \sigma }}{{\partial \varepsilon }}=0\)

where, σf and εf are the stress and strain of the full stress-strain curve of the cracked specimen at the peak stress.

The partial derivative is taken on both sides of Eq. (13), resulting in:

Substituting the geometric condition (1) into Eq. (13), the following is obtained:

Geometric condition (1) substituted into Eq. (14) yields:

Solving Eq. (16), we can get:

Geometric condition (1) is substituted into Eq. (17), leading to:

Equations (15) and (17) are combined, yielding:

Constitutive equation based on the power function distribution model

Substituting Eqs. (1) and (9) into Eq. (5), the total damage evolution equation is derived for rock with T-shaped cracks under loading conditions, where strain serves as the control variable for damage evolution.

Substituting Eq. (20) into Eq. (4) provides the constitutive equation for the rock mass with T-shaped cracks as:

Taking the partial derivative of both sides of Eq. (21) yields:

Substituting geometric condition (1) into Eq. (21) gives:

Substituting geometric condition (1) into Eqs. (5–24) results in:

Equation (24) is solved to yield:

Geometric condition (1) is substituted into Eq. (25), and we obtain:

Equations (25) and (27) are combined, yielding:

Constitutive equation based on the normal distribution model

Equations (1) and (11) are substituted into Eq. (5), the total damage evolution equation of T-shaped cracked rock mass under load with strain as the damage evolution control variable can be obtained: \({D_S}=1 - \frac{{{E_\phi }}}{{{E_0}}}+\frac{{{E_\phi }}}{{{E_0}}}\varphi \left( \varepsilon \right)\) (28)

Equation (28) is substituted into Eq. (4), resulting in the constitutive equation for the rock mass with T-shaped cracks as:

The partial derivative of both sides of Eq. (29) is taken, yielding:

Geometric condition (1) is incorporated into Eq. (29), yielding:

Geometric condition (2) is substituted into Eq. (30), producing:

Equation (32) is solved to get:

Geometric condition (1) is applied to Eq. (33), resulting in:

Equations (5–31), (5–35) and (5–36) are combined, we can get:

Results

Experimental results

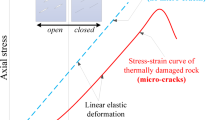

Figure 5 illustrates the stress-strain curves of single-crack and T-shaped crack specimens under triaxial compression conditions. The stress-strain relationship curve reflects the effect of crack inclination on the strength and deformation of the specimen, which is divided into four stages: compaction, elasticity, yield, and failure. Taking Fig. 5(a) as an example, during the initial compaction phase the stress-strain curve exhibits a concave-upward shape. The curve shifts leftward as the confining pressure increases, which can be attributed to the confining pressure restricting the deformation of the rock and enhancing its stiffness. In the elastic phase, the stress-strain curve exhibits a linear relationship and shifts upward as the confining pressure increases. This is attributed to the increased resistance of the rock to deformation under higher confining pressure, leading to a steeper stress-strain curve and a higher elastic modulus. The stress-strain curve exhibits a concave-down shape and shifts to the right during the yielding phase. This can be explained by the confining pressure restricting the initiation and propagation of internal cracks in the specimen, thereby enhancing the rock’s resistance to deformation and increasing its peak strength. In the failure phase, the curve gradually extends and moves upward due to the enhanced internal bonding force of the rock with higher confining pressure, leading to an increase in residual strength.

The failure modes of specimens with different crack angles are shown in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7. The peak strength of all single-crack specimens rises as confining pressure increases, though at a diminishing rate. Lower pressures primarily constrain deformation, while higher pressures induce distinct failure modes: shear failure at 0° inclination, tensile failure along the crack direction at 45°, and a combination of tensile and shear failure at 90°, all driven by stress concentration at crack tips. Through-going failure occurs in intact specimens at higher pressures. For T-shaped cracked specimens, when the primary crack inclination is 0° and the confining pressure increases from 0 MPa to 4 MPa, specimens with a primary-secondary crack angle of 30° and 60° experience shear failure at both ends of the primary crack and one end of the secondary crack due to stress concentration at the crack tips. Shear failure occurs at both ends of the primary crack in specimens with a 90° crack angle, while tensile failure develops along the secondary crack direction at one end of the secondary crack and the primary-secondary crack intersection. When the confining pressure increases from 4 MPa to 8 MPa, the failure modes remain the same as those observed at 4 MPa, but the peak strength exhibits a more pronounced increase. When the primary crack inclination is 45° and the confining pressure increases from 0 MPa to 4 MPa, specimens with a 30° primary-secondary crack angle undergo shear failure at both ends of the primary crack and one end of the secondary crack. Shear failure occurs at both ends of the primary crack due to stress concentration. For specimens with a 60° crack angle. In specimens with a 90° crack angle, shear failure occurs at both ends of the primary crack and one end of the secondary crack, while tensile failure extends along the secondary crack direction at the crack intersection. The failure modes remain consistent with those at 4 MPa as the confining pressure increases from 4 MPa to 8 MPa. However, for specimens with a 90° crack angle, no failure occurs at either end of the secondary crack, with shear failure confined to both ends of the primary crack. The peak strength increases more gradually compared to the 4 MPa condition.

In summary, in Under uniaxial compression conditions, single-fracture rock masses and T-shaped cracked rock masses fail upon reaching peak strength, indicating that the cracked rock specimens exhibit brittle elastic characteristics. When the confining pressure is between 0 MPa and 12 MPa, the decrease rate of the sample in the post-peak softening stage gradually slows down with the increase of strain, and then reaches a certain value. For both single crack and T-shaped crack specimens, when the crack angle is the same, the peak strength increases with rising confining pressure. This is because the increased confining pressure restricts the deformation of the rock. For single-fracture specimens, when the primary crack angle is 30° or 90°, shear failure occurs along a direction perpendicular to the primary crack. When the principal fracture angle is 45° and the confining pressure is 4 MPa, single crack specimens undergo tensile failure along the crack direction. When the confining pressure reaches 8 MPa or 12 MPa, single crack specimens experience shear failure perpendicular to the crack angle direction. For T-shaped crack specimens, when the primary crack inclination angle is 0° or 45°, the specimen generally expands in a direction perpendicular to the crack and undergoes shear failure. Except for the primary crack with an inclination angle of 90°, the T-shaped crack specimens undergo tensile failure in the secondary crack direction. When the primary crack angle is 90°, shear failure occurs at both ends of the primary crack of the T-shaped crack specimen due to the stress concentration at the tip. At the intersection of the primary and secondary cracks of the specimen, tensile failure occurred along the secondary crack direction of the specimen. Although the failure mode of the T-shaped crack specimen is different from that of the single crack specimen, its peak strength shows an upward trend compared to the peak strength of the T-shaped crack specimen at 0 MPa. The peak strength of T-shaped crack specimens increased by 4.28%, 2.24%, and 5.84% compared to single-crack specimens. This is attributed to the presence of the secondary crack, which bears part of the stress, thereby resulting in an increase in the peak strength of the T-shaped crack specimens. When the confining pressure is constant, the larger the angle between a single crack and the axial compressive stress, the smaller the peak strength of the specimen. However, the shapes of the pre-peak curves of different cracks are basically the same. For specimens with the same crack angle, the peak strength increases with rising confining pressure. This can be explained by the fact that at 0 MPa confining pressure, the specimens exhibit brittle behavior, whereas with an increase in confining pressure, the specimens transition from brittle to ductile.

Comparative study of damage constitutive models

Fitting was performed for the Weibull distribution model, power function distribution model, and normal distribution model, revealing that the power function distribution model is more suitable for T-shaped fractured rock. Subsequently, further analysis of the power function constitutive model, Weibull model, and normal distribution model is carried out using Origin software.

The stress-strain relationships of different single-crack specimens and T-shaped crack specimens under various conditions are shown in Fig. 6. Experimental data for single-crack and T-shaped crack specimens under uniaxial compression were compared with theoretical values from the power function distribution model, Weibull distribution model, and normal distribution model. Taking Fig. 6(a) as an example, the theoretical values of the power function model, Weibull model, and normal distribution model deviate from the experimental data by 0.56%, 16.4%, and 16.2%, respectively. This indicates a high degree of fit between the theoretical values of the power function model and the experimental data.

This indicates that the macroscopic damage, failure behavior, and damage evolution patterns of single-crack and T-shaped crack rocks under uniaxial compression can be effectively described by the power function distribution model. This is because the damage constitutive relationship established based on the power function distribution involves fewer unknown parameters and simpler relationships, allowing the peak strengths of single-crack and T-shaped crack rocks to be represented clearly and straightforwardly. However, the data fitting accuracy of the Weibull distribution model and the normal distribution model is lower than that of the power function distribution model. This is because the constitutive models established by the Weibull and normal distribution models involve more complex parameters and higher computational demands51, leading to greater errors.

The fitting of loading parameters across different models

The parameters m and ε0 are defined in Sect. 2.2, where m reflects the distribution concentration of the micro-element strength of the rock52,53, and ε0 reflects the macroscopic average strength of the rock54. The applicability of different models to single-crack and T-shaped crack rocks can be evaluated through the fitting of these two parameters. The damage constitutive equations of different models contain two unknown parameters, which can only be obtained by fitting the test data. After the mechanical parameters in Sect. 4.1 are processed, the parameters for the constitutive relations can be obtained. The mechanical parameters of T-shaped crack rocks are shown in Table 8.

The mechanical parameters in Table 8 were substituted into the damage constitutive models of the Weibull distribution function, the power distribution function and the normal distribution function. The fitting relationships for parameters m and ε0 under uniaxial compression conditions were obtained as shown in Fig. 7. The fitting correction coefficients were 0.90114, 0.95626 and 0.93416, respectively.

According to the above analysis, after the parameters m and ε0 of the three models are fitted, the fitting correction coefficients of the parameters m and a can be obtained. Finally, according to the degree of fit with the experimental data, it was concluded that the power function distribution model aligns most closely with the experimental data of the specimens. This indicates that the power function distribution model is more suitable for T-shaped cracked rock.

The relationship between parameter sensitivity and T-shaped crack inclination angles

The relationship between parameters m and the inclination angles of T-shaped cracks is illustrated in Fig. 8. When the primary crack inclination angle is 0°, parameter m decreases as the angle between the primary and secondary cracks increases. This is because parameter m reflects the concentration of the micro-element strength distribution in the rock55. Therefore, a larger m value indicates a more concentrated distribution of microelement strength and greater rock brittleness52,53. When the primary crack inclination is 0°, the crack inclination is perpendicular to the axial tensile stress, causing stress concentration at both ends of the crack. This leads to brittle failure of the rock and results in the lowest peak strength. As the angle between the primary and secondary cracks in T-shaped crack specimens increases, part of the stress field of the primary crack is redistributed, reducing the rock’s brittleness and gradually increasing its peak strength. When the inclination of the primary crack is 45° and 90°, the parameter m increases with the angle between the primary and secondary cracks. This is because the primary crack forms an angle with the axial stress. When the inclination angle is 45°, the crack surface bears part of the axial pressure. However, when the inclination angle is 90°, the crack surface does not bear axial pressure, leading to less pronounced brittle failure.

The relationship between parameter ε0 and the inclination angles of T-shaped cracks is shown in Fig. 9. When the primary crack inclination angle is 0°, parameter ε0 increases with the rise in the primary-secondary crack angle. However, when the primary crack inclination angles are 45° and 90°, parameter ε0 decreases as the primary-secondary crack angle increases. This can be explained by the fact that parameter ε0 represents the macroscopic average strength of the rock56. As ε0 increases, both the peak stress and strain of the rock increase.

Conclusion

-

(1)

Constitutive equations for crack damage in rocks were established for Weibull distribution model, the power function distribution model and the normal distribution model. Comparison results indicate that the power function distribution model is more suitable for T-shaped crack rocks.

-

(2)

The experimental data of single fissure and T-shaped fissure rocks under uniaxial compression conditions exhibit an excellent fit with the theoretical values of the power function distribution constitutive model. The rationality and suitability of this constitutive model are demonstrated.

-

(3)

When the primary fracture inclination is 0°, parameter m decreases while parameter ε0 increases with the increase in the angle between the primary and secondary fractures. When the primary fracture inclinations are 45° and 90°, parameter m increases while parameter ε0 decreases as the angle between the primary and secondary fractures increases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmed, Z., Wang, S., Hashmi, M. Z., Zhang, Z. & Zhu, C. Causes, characterization, damage models, and constitutive modes for rock damage analysis: a review. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 806 (2020).

Babanouri, N. & Fattahi, H. Constitutive modeling of rock fractures by improved support vector regression. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 243 (2018).

Sun, B., Yang, P., Luo, Y., Deng, B. & Zeng, S. Damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering structural features and load effect. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 62, 20230129 (2023).

Du, K. et al. Novel damage constitutive models and new quantitative identification method for stress thresholds of rocks under uniaxial compression. J. Cent. South. Univ. 31, 2658–2675 (2024).

Xu, J. & Li, Z. Damage evolution and crack propagation in rocks with dual elliptic flaws in compression. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 30, 573–582 (2017).

Xi, X., Wu, X., Guo, Q. & Cai, M. Experimental investigation and numerical simulation on the crack initiation and propagation of rock with Pre-Existing cracks. IEEE Access. 8, 129636–129644 (2020).

Taheri, A., Zhang, Y. & Munoz, H. Performance of rock crack stress thresholds determination criteria and investigating strength and confining pressure effects. Constr. Build. Mater. 243, 118263 (2020).

Liu, G. et al. Investigation of microcrack propagation and energy evolution in brittle rocks based on the Voronoi model. Materials 14, 2108 (2021).

Cheng, T. et al. Correlational fractal characteristics and damage progression of granite with different grain sizes based on acoustic emission monitoring. Eng. Geol. 327, 107358 (2023).

Liu, X. R., Yang, S. Q., Huang, Y. H. & Cheng, J. L. Experimental study on the strength and fracture mechanism of sandstone containing elliptical holes and fissures under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 205, 205–217 (2019).

Wang, Y., Deng, H., Deng, Y., Chen, K. & He, J. Study on crack dynamic evolution and damage-fracture mechanism of rock with pre-existing cracks based on acoustic emission location. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 201, 108420 (2021).

Cheng, T. et al. Experimental investigation on the influence of a single structural plane on rockburst. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 132, 104914 (2023).

Xue, F. et al. Experimental study on anchorage mechanical effect of rock bolts on cross-jointed rock mass using DIC and AE. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 137, 104875 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Strength criterion of rock mass considering the damage and effect of joint dip angle. Sci. Rep. 12, 2601 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Evaluation method of rock brittleness based on statistical constitutive relations for rock damage. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 153, 123–132 (2017).

Liu, H. Y., Lv, S. R., Zhang, L. M. & Yuan, X. P. A dynamic damage constitutive model for a rock mass with persistent joints. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 75, 132–139 (2015).

Liu, X. S., Ning, J. G., Tan, Y. L. & Gu, Q. H. Damage constitutive model based on energy dissipation for intact rock subjected to Cyclic loading. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 85, 27–32 (2016).

Yan, B. et al. Damage constitutive model and mechanical properties of jointed rock mass under hydro-mechanical coupling. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 123, 103735 (2023).

Yan, J. et al. Mechanical behavior and damage constitutive model of granodiorite in a deep buried tunnel. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 118 (2022).

Lu, T., Wu, H., Yin, S. & Xu, X. Study of rock damage constitutive model considering temperature effect based on Weibull distribution. Appl. Sci. -Basel. 14, 3766 (2024).

Xu, P. & Yang, S. Q. A fracture damage constitutive model for fissured rock mass and its experimental verification. Arab. J. Geosci. 10, 164 (2017).

Ji, M., Chen, K. & Guo, H. J. Constitutive Model of Rock Uniaxial Damage Based on Rock Strength Statistics. Adv. Civ. Eng. 5047834 (2018). (2018).

Lv, S., Wang, W. & Liu, H. A. Creep Damage Constitutive Model for a Rock Mass with Nonpersistent Joints under Uniaxial Compression. Math. Probl. Eng. 4361458 (2019). (2019).

Wu, L. et al. A continuous damage statistical constitutive model for sandstone and mudstone based on triaxial compression tests. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 55, 4963–4978 (2022).

Feng, T., Yu, X. & Cheng, G. Damage constitutive model of rock and application based on strength theory. J. Mech. 40, 336–353 (2024).

Gong, F., Zhang, P., Du, K. A. & Novel Staged Cyclic damage constitutive model for brittle rock based on linear energy dissipation law: modelling and validation. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 55, 6249–6262 (2022).

Kyoya, T., Ichikawa, Y. & Kawamoto, T. DAMAGE MECHANICS THEORY FOR DISCONTINUOUS ROCK MASS. Unkn. Host Publication Title 469–480 (1985).

Cai, M. & Horii, H. A constitutive model of highly jointed rock masses. Mech. Mater. 13, 217–246 (1992).

Wang, J. G., Ichikawa, Y. & Leung, C. F. A constitutive model for rock interfaces and joints. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 40, 41–53 (2003).

Deng, J. & Cu, D. On a statistical damage constitutive model for rock materials. Comput. Geosci. 37, 122–128 (2011).

Wang, Z., Zhu, Z. & Zhu, S. Thermo-mechanical-water migration coupled plastic constitutive model of rock subjected to freeze-thaw. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 161, 71–80 (2019).

Xie, L. X. et al. JHR constitutive model for rock under dynamic loads. Comput. Geotech. 108, 161–172 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. A constitutive model for rock materials subjected to triaxial Cyclic compression. Mech. Mater. 144, 103341 (2020).

Yu, D., Liu, E., Sun, P., Xiang, B. & Zheng, Q. Mechanical properties and binary-medium constitutive model for semi-through jointed mudstone samples. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 132, 104376 (2020).

Chang, L. et al. Analysis of failure characteristics and constitutive model development for sandstone with different ligament angles under biaxial loading based on infrared radiation. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 136, 104856 (2025).

Gengye, C., Lin & Yunmei, & Stress–strain–electrical resistance effects and associated state equations for uniaxial rock compression. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(03)00092-3 (2004).

Wu, Q. & Kulatilake, P. H. S. W. REV and its properties on fracture system and mechanical properties, and an orthotropic constitutive model for a jointed rock mass in a dam site in China. Comput. Geotech. 43, 124–142 (2012).

Wang, Y., Tang, J., Dai, Z. & Yi, T. Experimental study on mechanical properties and failure modes of low-strength rock samples containing different fissures under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 197, 1–20 (2018).

Wu, J., Feng, M., Han, G., Yao, B. & Ni, X. Loading rate and confining pressure effect on dilatancy, acoustic emission, and failure characteristics of fissured rock with two pre-existing flaws. C R Mec. 347, 62–89 (2019).

Han, W. et al. Numerical investigation on the shear behavior of rock-like materials containing fissure-holes with FEM-CZM method. Comput. Geotech. 125, 103670 (2020).

Castro-Filgueira, U., Alejano, L. R. & Ivars, D. M. Particle flow code simulation of intact and fissured granitic rock samples. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 12, 960–974 (2020).

Wang, Z., Fu, J., Wang, J., Li, S. & Feng, C. Numerical study on dynamic behavior and microscopic damage mechanism of 3D printed rock-like materials. Comput. Geotech. 173, 106495 (2024).

Liu, X., Li, D. & Han, C. Nonlinear damage creep model based on fractional theory for rock materials. Mech. Time-Depend Mater. 25, 341–352 (2021).

Lemaitre, J. How to use damage mechanics. Nucl. Eng. Des. 80, 233–245 (1984).

Chen, S. & Qiao, C. Composite damage constitutive model of jointed rock mass considering crack propagation length and joint friction effect. Arab. J. Geosci. 11, 283 (2018).

Wang, Z., Li, Y. & Wang, J. G. A damage-softening statistical constitutive model considering rock residual strength. Comput. Geosci. 33, 1–9 (2007).

Huang, S., Liu, Q., Cheng, A. & Liu, Y. A statistical damage constitutive model under freeze-thaw and loading for rock and its engineering application. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 145, 142–150 (2018).

Chen, K., Cudmani, R. & Pena, A. Assessment method for determining rock brittleness based on statistical damage constitutive relations. Geomech. Energy Environ. 37, 100517 (2024).

Chen, S., Qiao, C., Ye, Q. & Khan, M. U. Comparative study on three-dimensional statistical damage constitutive modified model of rock based on power function and Weibull distribution. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 108 (2018).

Zhu, Z. et al. A statistical thermal damage constitutive model for rock considering characteristics of the void compaction stage based on normal distribution. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 306 (2022).

Li, S., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Yang, J. & Lu, Z. Analysis on mechanical behavior and progressive failure of deep-buried marble based on complete stress-strain curves. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, 133 (2023).

Cao, H. et al. Applicability of rock damage model based on power law distribution. Acta Geophys. 72, 3021–3036 (2024).

Song, Z., Wang, T., Wang, J., Xiao, K. & Yang, T. Uniaxial compression mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of limestone under osmotic pressure. Int. J. Damage Mech. 31, 557–581 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. A study on the mechanical behavior and statistical damage constitutive model of sandstone. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 43, 5179–5192 (2018).

Feng, C., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Lu, Z. & Li, S. A thermo-mechanical damage constitutive model for deep rock considering brittleness-ductility transition characteristics. J. Cent. South. Univ. 31, 2379–2392 (2024).

Xie, S. et al. Constitutive modeling of rock materials considering the void compaction characteristics. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 22, 60 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202303021221042), the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202403021221119), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51504220).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. Conducted the experiments, analyzed the experimental data, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.S. N . Conceived and designed the study, supervised the research process, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content (corresponding author).J. W. Contributed to data interpretation, theoretical modeling, and validation of the damage constitutive models.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions statement

Miao Sun: Conducted the experiments, analyzed the experimental data, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. Shaoqing Niu: Conceived and designed the study, supervised the research process, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content (corresponding author). Jinwen Wu: Contributed to data interpretation, theoretical modeling, and validation of the damage constitutive models. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, M., Niu, S. & Wu, J. Deformation characteristics and damage model of T-shaped fractured rock mass with different inclination angles. Sci Rep 15, 15717 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00807-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00807-8