Abstract

LAP (lipid accumulation products) is a new indicator that estimates lipid overaccumulation and central obesity in our bodies. Nevertheless, the relationship of LAP with bone mineral density (BMD) has not been well established. This study aims to assess the association of LAP with BMD in U.S. adults. Multivariate linear regression was employed to detect the relationship of LAP with lumbar BMD in adult Americans. Subgroup and interaction tests were employed to detect the robustness of our findings. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) and threshold effect analysis were used to assess the nonlinear correlation of LAP with lumbar BMD. A total of 3883 participants consisted of 2117 (54.52%) men and 1766 (45.48%) women. The mean age of participants was 39.33 ± 11.53 years. After adjusting all covariates, we found a negative association of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD (β= -0.011, 95% CI: -0.019, -0.004). Threshold effect analysis identified the inflection points of 2.846. The results showed no correlation to the left of the saturation point but a significant negative correlation to the right. Interaction analyses indicated that all subgroups have no effect on this association (P > 0.05). Our study reported a nonlinear negative association of LAP with lumbar BMD. A large LAP may be associated with reduced BMD in American adults. These findings support the clinical utility of LAP as a predictor of osteoporosis and provide valuable insights into developing early intervention strategies for osteoporosis populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, one-fifth of the world’s population over the age of 50 have osteoporosis, causing a huge health and economic burden on society1. Characterized by low bone mass, osteoporosis patients have a higher risk of fragility fractures and their complications. The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) shows that globally, 158 million people aged 50 and over are at risk of osteoporotic fracture, which is estimated to double by 20402. The key determinants involving the development of osteoporosis include insufficient accumulation of peak bone mass during adolescence and excess bone loss during middle and old age3,4. Although many medications have been used for osteoporosis treatment, the side effects of medications still limit their use5,6. Therefore, recognizing and managing modifiable factors contributing to osteoporosis is essential for its prevention.

LAP (lipid accumulation products) is an assessment of the degree of lipid overaccumulation and central obesity, which is determined by serum triglyceride (TG) levels and waist circumference (WC)7. Recently, evidence showed that LAP was associated with many health conditions, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, osteoarthritis, and others8,9,10,11. For instance, Huang et al.9 found a nonlinear correlation between LAP and osteoarthritis in U.S. adults. They found a positive association between LAP and osteoarthritis when LAP < 120 cm × mmol/L, but no association when LAP > 120 cm × mmol/L. Ebrahimi et al.12found that LAP was a sensitive indicator to detect nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Obesity has been regarded as a significant risk factor for osteoporosis13. However, increasing evidence showed that WC and body mass index (BMI) are insufficient to accurately measure obesity because they do not differentiate between lean tissues, adipose tissue14.

To our knowledge, the association between LAP and BMD has not been well established. Examining the relationship between LAP and BMD may facilitate the recognition and prevention of osteoporosis. Thus, the objective of the study is to assess the relationship of LAP with lumbar BMD in American adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018.

Methods

Study design

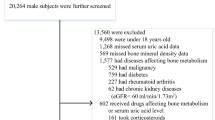

NHANES program is a national health and nutrition survey that carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NHANES utilizes a stratified, multi-stage, and complex design that recruits a demographically representative sample of the population in the United States. The use of data was approved by the ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics. Written consent was obtained from each participant. The survey included demographic, dietary, examination, dietary laboratory, and questionnaire data. In the present study, we enrolled four periods in NHANES: 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018. At first, we enrolled 39,156 subjects from NHANES 2011–2018. Then, we excluded individuals who were younger than 20 years (n = 16,539), individuals who lost information on lumbar BMD (11,086), LAP (6,402), and other covariates (1,246). Finally, 3,883 subjects were enrolled in our study (Fig. 1).

LAP index calculation

LAP was an exposure variable in the present study, which is calculated in accordance with previous literature12. [WC (cm)−65] × [TG (mmol/l)] for men and [WC (cm)−58] × [TG (mmol/l)] for women12. For WC assessment, a measuring tape was positioned at the point where the horizontal line above the top of the right kneecap intersects with the midaxillary line. Concentration of triglyceride was measured using the Roche Modular P and Roche Cobas 6000 chemistry analyzers.

Assessment of lumbar spine BMD

The lumbar spine BMD was the outcome variable in our study. Between 1999 and March 2020, BMD measurements were performed using a Hologic QDR-4500 A fan-beam densitometer (Hologic Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts). BMD information was analyzed using Hologic software version 8.26 and Hologic Discovery v12.4. More recently, beginning in 2017, spine scans were acquired on a Hologic Horizon Model A densitometer using software version Apex version 5.6.0.5, and BMD data were analyzed using Hologic APEX version 4.0 software. All scans conformed to the guidelines of the International Society for Clinical Bone Densitometry (ISCD). Detailed information on the DXA exam can be found on the NHANES website15.

Covariates

In the present study, covariates covered age, race, gender, education level, BMI, poverty income ratio (PIR), total protein, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, cholesterol, serum vitamin D, drinking and smoking behaviors, high blood pressure, diabetes, physical activity, and Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015). Drinking and smoking behaviors, high blood pressure, diabetes, and physical activity were measured by a questionnaire: Have you ever had 5 or more drinks every day? Did you smoke at least 100 cigarettes in life? Ever told you had high blood pressure? The doctor told you had high blood diabetes? Did you have vigorous work activity in a typical week? HEI-2015 is a density-based index calculated based on dietary nutrient intake per 1,000 kcal rather than absolute amounts16. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better dietary quality16. More detailed information can be found on the NHANES website.

Statistical analysis

The participants’ characteristics were expressed by LAP quartile. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation with weighted linear regression models. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages with weighted χ2 tests. Multivariate linear regression was employed to analyze the linear association of Ln-LAP with lumbar BMD. We use ln-LAP rather than LAP because the LAP range is so large that it is difficult to make an impact on the outcome through a one-unit change. Model 1 adjusted no covariate. Model 2 adjusted for variables of age, race, and gender. Model 3 adjusted for variables of age, race, gender, education level, BMI, PIR, total protein, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, cholesterol, serum vitamin D, drinking and smoking behaviors, high blood pressure, diabetes, physical activity, and HEI-2015. Subgroup and interaction analyses were conducted by gender (men and women), age (< 35, 35–50 and > 50), race (Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, and Other Race), and BMI (< 25, 25–30, > 30), education level (College degree or above, Under high school, and High school graduate), PIR (< 1.3, 1.3–3.5, > 3.5), Hypertension (Yes, No), Diabetes (Yes, No, Borderline), drinking and smoking behaviors, physical activity. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) with three knots located at the 5 th, 50 th and 95 th were conducted to explore the nonlinear relationship of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD. Threshold effect analyses were conducted by a two-segment linear regression model with both parts of the infection point using a recursive algorithm. P-values less than 0.05 were deemed as statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 3,883 participants, consisting of 2117 (54.52%) men and 1766 (45.48%) women. The mean age of participants was 39.33 ± 11.53 years. The population consists of 1528 (39.35%) Non-Hispanic White, 794 (20.45%) Non-Hispanic Black,

649 (16.71%) Other Race, 533 (13.73%) Mexican American, and 379 (9.76%) Other Hispanic. Moreover, in comparison to participants with lower LAP, participants with higher LAP showed a larger likelihood of being older, men, Mexican American, Non-Hispanic White, less educated, and more frequently drinking and smoking. They have higher BMI, cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, and HEI-2015 values and lower PIR, serum vitamin D, serum phosphorus, and lumbar BMD. They are more likely to have diabetes, high blood pressure, and more physical activity (Table 1).

Associations between LAP and lumbar spine BMD

The relationship of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD is illustrated in Table 2. We reported a negative association of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD in model 1 (β= −0.012, 95% CI: −0.017, −0.007) and model 2 (β= −0.005, 95% CI: −0.009, −0.002). In the fully adjusted model (model 3), we found a negative association of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD (β= −0.011, 95% CI: −0.019, −0.004). Participants in the fourth quartile of ln-LAP have a significantly reduced lumbar BMD than participants in the first quarter (β= −0.038, 95% CI: −0.057, −0.021) (P for trend < 0.001). The RCS indicated a nonlinear negative correlation of ln-LAP with lumbar BMD (P for nonlinear < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Analyzing the images, no significant association was found between ln-LAP and lumbar spine BMD within a certain range. When exceeding a certain value, a significant negative correlation was found between ln-LAP and lumbar BMD. Then, threshold effect analysis identified the inflection points of 2.838 (Table 3). When ln-LAP < 2.838, no association was found between ln-LAP and lumbar BMD (β = 0.011, 95% CI: −0.007, 0.029). When ln-LAP > 2.846, a significant negative association was detected between ln-LAP and lumbar BMD (β= −0.029, 95% CI: −0.050, −0.006).

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis with multivariate-adjusted associations between ln-LAP and lumbar spine BMD. Age, race, gender, education level, BMI, PIR, total protein, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, cholesterol, serum vitamin D, drinking and smoking behaviors, high blood pressure, diabetes, physical activity, and HEI-2015 were adjusted. Abbreviation: PIR: poverty income ratio. BMI: body mass index. Lipid accumulation products: LAP. HEI-2015: Healthy Eating Index-2015.

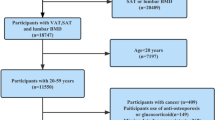

Subgroup and interaction analyses

Subgroup and interaction analyses were performed by age, race, gender, BMI, education level, PIR, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and drinking behaviors, and physical activity (Fig. 3). The results indicated that all subgroups have no significant effect on this correlation (P for interaction > 0.05).

Subgroup and interaction analyses of the association between LAP and lumbar BMD. Age, race, gender, education level, BMI, PIR, total protein, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, cholesterol, serum vitamin D, drinking and smoking behaviors, high blood pressure, diabetes, physical activity, and HEI-2015 were adjusted. Abbreviation: PIR: poverty income ratio. BMI: body mass index. LAP: Lipid accumulation products. HEI-2015: Healthy Eating Index-2015.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the correlation of ln-LAP with lumbar spine BMD in a large, nationally representative American population. After adjusting covariates, we observed a nonlinear negative relationship between ln-LAP and lumbar spine BMD. Furthermore, we found that the subgroups had no interactive effects on this association. These findings support the clinical utility of LAP as a predictor of osteoporosis and provide valuable insights into the development of early intervention strategies for osteoporosis populations.

This is a large-scale study to explore the possible relationship of LAP with bone health. Previously, obesity has been recognized as a key factor in bone health and fragility fractures17. BMI and WC are two recognized parameters for identifying obesity17. Many studies have investigated the relationship of BMI and WC with BMD but report conflicting results. In a study of 2218 participants from NHANES 2011–2018, Li et al.18 found that BMI was positively related to lumbar BMD after adjusting covariates. Ma et al.19 indicated a positive association between BMI and BMD by a Mendelian randomization approach. In another study by Pan et al.20, they found that a higher WC was positively associated with femur and spinal BMD in U.S. adults. In a study of 5084 adults aged 40–59 years, Hua et al.21 found a negative relationship between WC and lumbar BMD, and this relationship was independent of BMI. In a study by Chen et al.22, they concluded an inverted U-shape relationship of WC with femur BMD in individuals aged 60 years or older, and the inflection point is 95 cm for both men and women. An increasing number of specialists believe that WC and BMI are insufficient to accurately measure obesity because they do not differentiate between lean tissues and adipose tissue23. Compared to traditional indicators, LAP is an indicator determined by WC and TG that accurately reflects visceral fat accumulation24. Studies have shown that LAP is more likely to identify the risk of diabetes or cardiovascular disease than BMI or WC12,25,26. In addition, many papers recently present evidence that LAP may also serve as a potential marker for a variety of other health conditions. Huang et al.9 found a positive association between LAP and risk of OA when LAP < 120.00 cm × mmol/L, while no association when LAP > 120 cm × mmol/L in NHANES 2017–2020. In a study of 9781 U.S. adults, Zhang et al.27 indicated that LAP was positively related to psoriasis after adjusting a large of covariates. Recently, a study by chen et al.28, they found a significant saturation effect between LAP and total femoral BMD in 3223 adults aged 20 years and older. However, the study was not adjusted for BMI and could not get rid of the interference of BMI on the results. Our study found a nonlinear negative association between LAP and BMD in U.S. adults after adjusting a large number of covariates including BMI. Thus, our results suggested that a nonlinear negative association between LAP and BMD exists independently of BMI. This is important because usually BMI does not accurately distinguish between lean tissues and adipose tissue, and thus our study could better reflect the relationship between LAP and BMD. Specifically speaking, the RCS and threshold analyses indicated that there are no significant association between ln-LAP and lumbar BMD when ln-LAP < 2.846 and a significant negative association when ln-LAP > 2.846. This result is similar to a previous study exploring the relationship between WC and BMD21. Hua et al.21 found no association of WC with lumbar BMD in premenopausal women when WC < 80 cm and a negative association with WC > 80 cm. Similarly, there is a threshold association between LAP and total spine BMD, with no correlation LAP and BMD before the threshold is reached and a negative correlation between LAP and BMD after the threshold is exceeded.

The specific mechanisms of LAP with bone health and BMD are unclear and complex. The effect of obesity on BMD involves mechanical effects, endocrine alterations, and increased inflammatory factors29. First, the accumulation of excess body fat and increased levels of obesity lead to an increase in static mechanical compliance, which imposes a variety of static mechanical stresses on the skeleton and induces changes in bone structure(30,31). Second, osteoblasts and adipocytes in bone marrow originate from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). Obesity leads to decreased differentiation of BMSCs to osteoblasts and increased differentiation to adipocytes32. Third, the expansion of adipocytes in the bone marrow microenvironment suppresses osteoblast differentiation and accelerates the release and activation of inflammatory and immunomodulatory factors that promote osteoclast formation and inhibit osteoprotegerin secretion33. In obesity, adipocyte hypertrophy is accompanied by adipose tissue expansion, which causes adipose tissue to release more leptin and less adiponectin33. These alterations contribute to systemic inflammation, insulin resistance and skeletal disorders in obesity34. Furthermore, it has been shown that enhanced insulin signaling leading to obesity-induced hypermetabolism accelerates metabolic senescence of BMSCs35. These mechanisms may explain the nonlinear negative correlation between LAP and lumbar BMD. It is worth noting that we adjusted for BMI in the final analysis, so this relationship existed independently of BMI. Therefore, LAP could be a new indicator to predict bone health. However, further research is needed to elucidate the specific mechanism of LAP in BMD.

Our results have some advantages. First, this cross-sectional survey used a large sample, and all analyses were adjusted by MEC weight, which could represent the general American population. Second, we adjusted for many confounders to ensure the reliability of our findings. Third, there is a nonlinear correlation between LAP and BMD, further demonstrating the existence of the threshold phenomenon. Fourth, another noteworthy point is that all subgroups have no interactive effect on this relationship, so the results have applicability to different populations. Our study also has some limitations. First, causal inferences cannot be inferred because of the nature of the cross-sectional study. Second, we did not analyze the relationship of LAP with femur BMD because of relevant data in NHANES cycles were missing. Thus, further studies are need to explore the association between LAP and femur BMD. Third, other potential confounders not adjusted for in the present research may still affect the results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study reported a nonlinear negative correlation between LAP and lumbar BMD in U.S. adults. A large LAP may be associated with reduced BMD. These findings support the clinical utility of LAP as a predictor of osteoporosis and provide valuable insights into the development of early intervention strategies for osteoporosis populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NHANES] repository, [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/].

Abbreviations

- LAP:

-

(lipid accumulation products)

- (BMD):

-

Bone mineral density

- (RCS):

-

Restricted cubic spline

- (IOF):

-

International Osteoporosis Foundation

- (TG):

-

Triglyceride

- (WC):

-

Waist circumference

- (NAFLD):

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- (BMI):

-

Body mass index

- (NHANES):

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- (NCHS):

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- (DXA):

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- (BMSCs):

-

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- (HEI-2015):

-

Healthy Eating Index-2015

References

Xiao, P. L. et al. Global, regional prevalence, and risk factors of osteoporosis according to the world health organization diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 2137–2153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-022-06454-3 (2022).

Hsu, C. Y. et al. Regular exercise and Weight-Control behavior are protective factors against osteoporosis for general population: A propensity Score-Matched analysis from Taiwan biobank participants. Nutrients 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030641 (2022).

Akhiiarova, K., Khusainova, R., Minniakhmetov, I., Mokrysheva, N. & Tyurin, A. Peak Bone Mass. Formation: Mod. View Problem Biomedicines ;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11112982 (2023).

Lo, J. C., Yang, W., Park-Sigal, J. J. & Ott, S. M. Osteoporosis and fracture risk among older US Asian adults. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 21, 592–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-023-00805-7 (2023).

Nashi, M. et al. Incidence of antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A multicenter retrospective epidemiological study in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. J. Dent. Sci. 18, 1156–1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2022.10.030 (2023).

Srivastava, A. et al. Prevalence of medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with sequential antiresorptive drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 29, 2305–2317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05882-3 (2021).

Yang, S. H., Yoon, J., Lee, Y. J., Park, B. & Jung, D. H. Lipid accumulation product index predicts New-Onset type 2 diabetes among Non-Obese Koreans: A 12-Year longitudinal study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 15, 3729–3737. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S389889 (2022).

Qiu, J. et al. The predictive significance of lipid accumulation products for future diabetes in a non-diabetic population from a gender perspective: an analysis using time-dependent receiver operating characteristics. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1285637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1285637 (2023).

Huang, J. et al. Association between lipid accumulation products and osteoarthritis among adults in the united States: A cross-sectional study, NHANES 2017–2020. Prev. Med. 180, 107861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2024.107861 (2024).

Huang, Q. et al. Lipid accumulation product is a valid predictor of hepatic steatosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomark. Med. 18, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2023-0725 (2024).

Liu, Q., Huang, Y., Wang, M., Jiang, H. & Zhang, X. Association of lipid accumulation products with testosterone deficiency in adult American men: A cross-sectional study. Andrology 11, 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.13355 (2023).

Ebrahimi, M. et al. Lipid accumulation product (LAP) index for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 22, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01802-6 (2023).

Martiniakova, M. et al. Links among obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis: bone as a target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25094827 (2024).

Jackson, A. S. et al. The effect of sex, age and race on estimating percentage body fat from body mass index: the heritage family study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 26, 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802006 (2002).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 1591–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.021 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. The effect of overweight or obesity on osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 42, 2457–2467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2023.10.013 (2023).

Li, Y. Association between obesity and bone mineral density in middle-aged adults. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17, 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03161-x (2022).

Ma, W., Zhou, X., Huang, X. & Xiong, Y. Causal relationship between body mass index, type 2 diabetes and bone mineral density: Mendelian randomization. PLoS One. 18, e0290530. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290530 (2023).

Pan, R. et al. The association of waist circumference with bone mineral density and risk of osteoporosis in US adult: National health and nutrition examination survey. Bone 185, 117134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2024.117134 (2024).

Hua, Y., Fang, J., Yao, X. & Zhu, Z. Can waist circumference be a predictor of bone mineral density independent of BMI in middle-aged adults? Endocr. Connect. 10, 1307–1314. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-21-0352 (2021).

Chen, J., Zhu, L., Yao, X. & Zhu, Z. The association between abdominal obesity and femoral neck bone mineral density in older adults. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03654-3 (2023).

Lam, B. C., Koh, G. C., Chen, C., Wong, M. T. & Fallows, S. J. Comparison of body mass index (BMI), body adiposity index (BAI), waist circumference (WC), waist-To-Hip ratio (WHR) and waist-To-Height ratio (WHtR) as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in an adult population in Singapore. PLoS One. 10, e0122985. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122985 (2015).

Lwow, F., Jedrzejuk, D., Milewicz, A. & Szmigiero, L. Lipid accumulation product (LAP) as a criterion for the identification of the healthy obesity phenotype in postmenopausal women. Exp. Gerontol. 82, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.06.007 (2016).

Kahn, H. S. The lipid accumulation product performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: a population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-5-26 (2005).

Ma, C. M. et al. Three novel obese indicators perform better in monitoring management of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 7, 9843. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10446-3 (2017).

Zhang, C., Dong, X., Chen, J. & Liu, F. Association between lipid accumulation product and psoriasis among adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02123-y (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Lipid accumulation product, poverty income ratio, and bone mineral density in U.S. Adults: a mediation analysis based on NHANES (2009–2020). Front. Nutr. 11, 1466288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1466288 (2024).

Rinonapoli, G. et al. Obesity and bone: A complex relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413662 (2021).

Hla, M. M. et al. A multicenter study of the influence of fat and lean mass on bone mineral content: evidence for differences in their relative influence at major fracture sites. Early postmenopausal intervention cohort (EPIC) study group. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/64.3.345 (1996).

Lanyon, L. E. Control of bone architecture by functional load bearing. J. Bone Min. Res. 7 (Suppl 2), S369–S375. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650071403 (1992).

Khan, A. U., Qu, R., Fan, T., Ouyang, J. & Dai, J. A glance on the role of actin in osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 11, 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-020-01789-2 (2020).

Forte, Y. S., Renovato-Martins, M. & Barja-Fidalgo, C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms associating obesity to bone loss. Cells 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12040521 (2023).

Fasshauer, M. & Blüher, M. Adipokines in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36, 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.014 (2015).

Tencerova, M. et al. Obesity-Associated hypermetabolism and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal stem cells suggest a potential mechanism for bone fragility. Cell. Rep. 27, 2050–2062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.066 (2019). e6.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, Aiyong Cui, Yan Zhuang; Data curation, Aiyong Cui, Xing Wei; Formal analysis, Xing Wei, Yan Zhuang, Shuang Han; Investigation, Aiyong Cui, Yan Zhuang; Methodology, Aiyong Cui, Shuang Han; Project administration, Aiyong Cui Software, Aiyong Cui Visualization, Aiyong Cui, Xing Wei; Writing – original draft, Aiyong Cui, Xing Wei Writing – review & editing, Aiyong Cui, Yan Zhuang, Shuang Han. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

Aiyong Cui, Xing Wei, Hu Wang, Yan Zhuang, and Jing He declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, A., Zhuang, Y., Wei, X. et al. The association between lipid accumulation products and bone mineral density in U.S. Adults, a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 16373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00833-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00833-6