Abstract

The visible light vegetation indices (VIs) derived from the red, green, and blue spectral bands of UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) imagery play a vital role in precision agriculture applications. Nevertheless, the effects of solar elevation angle variations across different flight times remain poorly understood. The DJI Phantom 4 RTK high-precision positioning aerial survey UAV was used to conduct a timed flight over cotton plots with both weak growth without nitrogen application and strong growth with nitrogen application. The visible light VIs for 13 UAVs at 12 different flight times were extracted, and a one-dimensional linear regression model established. By comparing the difference significance and slope values of the models, to evaluate the influence degree of solar elevation angle and cotton growth on the visible light VIs of 13 kinds of UAV, so as to provide a reference for the reasonable planning of UAV flight time under the background of precision agriculture. The results show that: (1) No matter in the test plots with relatively weak or prosperous cotton growth, Solar elevation angle was always significantly positively correlated with the excess red vegetation index (ExR) and red-green ratio index (RGRI). There was a significant linear negative correlation with the excess green minus excess red vegetation index (ExGR), excess green vegetation index (ExG), red-green-blue vegetation index (RGBVI), modified green-red vegetation index (MGRVI), green leaf index (GLI), normalized green-red difference index (NGRDI), and visible atmospherically resistant index (VARI), but there was no significant linear regression relationship with the Kawashima index (IKAW). (2) In the test plot without nitrogen application with relatively weak cotton growth, the linear regression model of visible light vegetation index (green-blue ratio index GBRI, excess blue vegetation ExB, normalized green-blue difference index NGBDI) and Solar elevation angle of cotton field is more likely to reach a significant level. (3) The effect of the solar elevation angle on ExG, ExGR, GLI, ExB, RGBVI, NGBDI and GBRI can be reduced in the test plot with nitrogen application with relatively strong cotton growth, and the effect on ExR, NGRDI and MGRVI can be increased. (4) Solar elevation angle had the greatest influence on ExGR, RGBVI, and MGRVI, and IKAW was the least influential. Therefore, it is suggested in this study that when the visible light VIs of ExGR, RGBVI, MGRVI are applied to the growth monitoring and evaluation of cotton fields, the flight time (or solar elevation angle) of UAVs should be as consistent as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The vegetation index (VI) is a dimensionless, unique spectral signal extracted from the optical parameters of the leaf canopy. It is an empirical or semi-empirical vegetation observation method applicable to most biological groups. It is widely used in dryland detection, vegetation coverage, crop changes, productivity analyses, and other fields1,2. According to the division of UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) camera sensors, it can be divided into visible light VIs (visible-range camera), multispectral VIs (multispectral camera) and hyperspectral VIs (hyperspectral camera). Although multispectral VIs is the most widely used, considering the sensor cost and to meet the demand of a low consumer market, the visible light VIs based on RGB image is still widely used3,4. Visible light VI is also called visible spectrum/band vegetation index5,6, visible vegetation index7,8, RGB-based vegetation index or RGB vegetation index9,10,11,12,13,14,15, and color index16,17,18.

Hammond et al.7 used the visible light camera of a UAV to extract a variety of visible light VIs, such as ExG, ExR, ExGR, and MGRVI, and evaluated the correlation between them and the leaf area index. Among them, the prediction accuracy of visible light VIs such as MGRVI, NGRDI, and ExR reached good levels. Yuefeng et al.19 used the visible vegetation indices ExG, NGRDI, VDVI, MGRVI, and RGBVI obtained using a UAV to extract desert vegetation data and compared the results with the vegetation index L2AVI (L-a-a vegetation index) of the Lab color space. The results showed that the extraction accuracy of the vegetation based on the visible light VIs was more than 70%. Roth et al.5 used the visible vegetation indices VARI, GLI, MGRVI, RGBVI, and ExG obtained using UAVs to predict the accumulation of cereal rye biomass, C, N, P, K, and S. The results showed that different visible light VIs had different forecasting effects on these indicators.

Cotton is an important cash crop in Xinjiang, as it has the largest planting area and output in China. In 2022, the cotton planting area of Xinjiang was 3.5 × 106 hm2, accounting for 83.2% of China’s cotton planting area, and the output was 5.391 million tons, accounting for 90.2% of China’s total cotton production. Xinjiang has a superior geographical environment due to its long sunshine durations, sufficient light source, short frost-free period, and high accumulated temperature, which makes it suitable for cotton cultivation20,21,22. A stable and high cotton yield is thus key to ensuring China’s economic development23. Healthy development of the cotton industry is related to the development of the local agricultural industry and is an important source of economic income for local farmers24. The growth conditions of cotton in the early stages are key factors in determining its healthy growth and achieving stable and high yields. UAV remote sensing technology has been increasingly applied to cotton production and scientific research in Xinjiang25,26,27. The UAV visible light VIs has been successfully used in cotton yield inversion28, cotton leaf area monitoring29, nitrogen and chlorophyll inversion30, and seedling monitoring31. The data shows that the visible light VI plays an important role in the application of cotton.

When the VI is extracted from the visible images produced by the UAV, the extraction accuracy and effects have been found to be impacted by many factors, such as flight height, solar elevation angle (time), and weather changes. These results indicate that reasonable flight plans will help to improve the accuracy of crop information acquisition and have an important role in the significance of research to help optimize flight strategies, improve flight efficiencies, and reduce operating costs. The solar elevation angle changes with time during the day.

However, most studies on the influence of the solar elevation angle on VIs have focused on multispectral and hyperspectral VIs. For example, the influence of zenith angle and EVI (enhanced vegetation index) was studied by Brede et al.32 using UAV hyperspectral imager. Under the lowest observation conditions, the linear trend of EVI with solar zenith angle is − 0.003, and the change of solar elevation angle directly causes the change of vegetation shadow, compared with NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index), EVI is more sensitive to vegetation shadow. Therefore, the change of solar elevation angle will undoubtedly have different effects on NDVI and EVI. The relationship between solar elevation angles was studied by Yang et al.33 using multi-spectral vegetation index NDVI and EVI. They found that NDVI increased and EVI decreased with the increase of solar elevation angle. Jiang et al.34 using the multi-spectral camera of the drone in the paddy field also confirmed that NDVI will indeed be affected by the solar elevation angle. They found that with the increase of the solar elevation angle, NDVI will gradually increase.

There are few reports on the relationship between solar elevation angle and the visible light VIs, and in-depth and systematic studies on various visible light VIs are still lacking. To address this, this study has used a DJI Phantom 4 RTK multi-rotor small UAV to acquire visible light remote sensing images of UAV under different solar elevation angles and growth levels cotton without or with nitrogen application. The influence of different solar elevation angles on the visible light VIs and its relationship were studied to provide a reference for the rational and efficient use of UAV in precision agriculture.

Materials and methods

Field experiment design

This study was conducted at the Alar Experimental Station of the Cotton Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Alar 10th Regiment, 1st Division, Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, 40.605 °N, 81.313 °E). The soil type at the experiment station was forest irrigated meadow soil, and the organic matter, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, total potassium, alkali-hydrolytic nitrogen, and available phosphorus content were 11.54 g/kg, 0.65 g/kg, 0.93 g/kg, 21.26 g/kg, 50.17 mg/kg, and 55.70 mg/kg, respectively.

For this study, Tahe No. 2 upland cotton was used. The field trial consisted of five treatments: treatment 1 was the control (no nitrogen fertilizer application); treatment 2 used the conventional nitrogen fertilizer application rate (total nitrogen application rate of 400 kg N/hm2); treatment 3 used a nitrogen reduction rate of 20% (320 kg N/hm2); treatment 4 used a nitrogen reduction rate of 20% + chitosan oligosaccharide type 1; and treatment 5 used a nitrogen reduction rate of 20% + chitosan oligosaccharide type 2.

Chitosan oligosaccharides type 1 and type 2 were provided by Dalian Zhongkegelaike Biotechnology Co. Ltd. and Qingdao Songtian Biotechnology Co. Ltd., respectively. The polymerization degrees were 2–6 and 2–20, respectively, and the application amounts were 450 g/hm2 each time for a total of eight times. The Annual total usage for the phosphate and potassium fertilizers were 140 kg/hm2 and 130 kg/hm2, respectively. Each treatment was repeated six times, and 30 plots were arranged in random blocks with lengths, widths, and areas of 8 m, 6.84 m, and 54.72 m2, respectively. Seeds were sown on 12 April 2023, using the wide-narrow row planting mode for machine-picked cotton, with a row spacing of 65 cm + 10 cm and plant spacing of 10 cm. Each plastic film had six rows, and the theoretical density was 2.58 × 105 plants/hm2. Fertilizer and chitooligosaccharides were applied using integrated water and fertilizer facilities, and each plot was irrigated and fertilized, and chitooligosaccharides were applied separately. One plot without fertilization treatment (No: plot I-1) had poor or weak cotton growth (average plant height of 69.3 cm/plant), and one plot with treatment 5 (No: plot I-5) had vigorous or strong cotton growth (average plant height of 71.7 cm/plant). These areas represented cotton fields with low and high coverage, respectively.

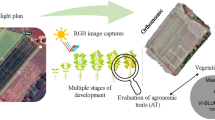

Acquisition of UAV remote sensing data

A DJI Phantom 4 RTK small multi-rotor high-precision aerial survey UAV (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to build maps and capture aerial photos of the cotton experimental field. Phantom 4 RTK integrates a new RTK module, with more powerful precision positioning capabilities, providing real-time centimeter-level positioning data, significantly improving the absolute accuracy of image metadata. The horizontal positioning accuracy can reach 1 cm + 1 ppm, and the vertical positioning accuracy can reach 1.5 cm + 1 ppm. The Phantom 4 RTK have high-precision optical imaging systems, and a 1 inch 2 × 107 megapixel CMOS sensorthat can capture high-definition videos and images (https://enterprise.dji.com/cn/phantom-4-rtk).

Flight missions were programmed using DJI Pilot software with the following parameters: 13 m altitude on 26 August and 31 August, and 39 m altitude on 1 September, 80% course and side overlap rates, and 1 m/s route speed. Photography mode was set to equal time intervals, and shooting parameters were set as follows: ISO = 100, shutter = 1/240, EV = 0, and auto focus was used. The aerial photography of the whole cotton experimnetal field is 0.31 hm2, with a flight length of 16 min, a route length of 904 m, 35 waypoints, and 383 photos.

Three cloudless days (26 August, 31 August, and 1 September 2023) with wind speeds of < 2.5 m/s were selected and the identified route was flown over the cotton experimental field with the Phantom 4 RTK every hour from 8:30 to 21:00. Each day involved 12 flights and approximately 13,800 photos were obtained.

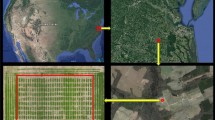

Aerial photography of the Phantom 4 RTK drone prepares photos and Phantom 4 RTK multirotor UAV visible light image of the cooton experimental field on 14 July 2023. From left to right (west to east) the columns are numbered I, II, III, IV, V, and VI. The upper left corner (northwest) is plot I-1 (I repeat treatment 1 without nitrogen fertilization), and the lower left corner (southwest) is plot I-5 (I repeat treatment 5 with nitrogen fertilization).

Processing of digital orthophoto data

After aerial shooting, the original photos taken by the Phantom 4 RTK camera were input to the DJI Terra software, farmland scenes were selected, visible light 2D reconstruction tasks were performed, and an ultra-high-resolution digital orthographic map (DOM) with an average pixel size of 0.36 cm/pixel was produced. Figure 1 shows the aerial preparation photos of the Phantom 4 RTK UAV and the visible light remote sensing image of the UAV at the cotton experimental field acquired on 14 July 2023.

Lite RTK (Wuhan Hengshen Engineering Technology Co., Ltd. see Fig. 2) was used to obtain 12 ground control points in the cotton experimental field, and an ultrahigh-resolution digital orthophoto image of the Phantom 4 RTK UAV was calibrated with geometric precision. As the Lite RTK and Phantom 4 RTK drones both use the RTK high-precision positioning service of QIANXUN Location Service, the ground control points almost coincide with the corresponding points on the UAV digital orthophoto map, so there is no need to perform geometric precision correction on the digital orthophoto map.

The DOM file was input into ArcMap 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., ESRI), and two sub-regions with the same shape and area were cut out from the 1st repeat treatment 1 (No. plot I-1) and treatment 5 (No. plot I-5), representing cotton fields with relatively weak and prosperous growth, respectively. The visible images from the UAV for the cotton field sub-regions I-1 and I-5 were input into ArcMap 10.8 software, and a Python program was written using the ArcPy library to normalize the gray level or radiation brightness value (digital number, DN) of the red, green, and blue channels of the UAV-visible images, expressed by R, G, and B, respectively.

Calculation of the visible light VIs

At present, there are three main methods to calculate the visible light VIs. Let’s take ExG as an example to illustrate these three calculation methods.

Method (1): Calculate visible light VIs directly from the DN values of the R, G, and B bands15,35,36:

Method (2): First, normalize the DN values of the R, G, and B bands, then use the normalized values to calculate visible light VIs10,12,14,37,38,39:

Where, r, g and b are normalized DN values of R, G and B bands, respectively. The values for r, g, and b, each range from 0 to 1.

Method (3): Calculate visible light VIs using the reflectance values of R, G, and B bands14:

Where, r*, g* and b* are normalized spectral reflectance of the R, G, and B bands, respectively. Spectral reflectance was the result of the radiometric calibration40.

Among the three methods for calculating the visible light VIs mentioned above, method (1) is the most convenient to calculate; The visible light VIs calculated by method (2) can reduce the influence of light and shadow10,16, and have many applications; In theory, method (3) may be the most accurate, but it requires the use of a calibrated solar diffuser reflectance panel to convert DN values. This experiment did not place calibrated solar diffuser reflectance panels in the cotton field, therefore, the method (2) was chosen to calculate the visible light VIs. In this study, the visible light VIs of the 13 types of UAVs, shown in Table 1, were calculated.

Results

Solar elevation angles and meteorological indicators at different flight times

Adopting the global monitoring laboratory of the NOAA Solar Calculator online Solar Elevation Angle Calculator (https://gml.noaa.gov/grad/solcalc/), the solar elevation angle was determined for each of the three days. The test site was the local solar elevation angle at each time the UAV began taking aerial photos of the first field trial plot.

The wind direction and speed, air pressure, temperature and humidity measured during the flight on 26 August 2023 are listed in Table 2. (See Appendix A for meteorological indicators measured on 31 August and 1 September 2023), and the solar elevation angles at different flight times on 26 and 31 of August and 1 September 2023 are shown in Fig. 3.

Influence of solar elevation angles on the red, green, and blue pixel values of the UAV visible remote sensing images

The visible light images for field plots I-1 and I-5 are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. These plots were selected from 30 test plots on 26 August that were used to evaluate whether there were differences in the influence of the solar elevation angle on the visible VIs of the cotton field, with two cotton growth conditions. Visible light images for field plots I-1 and I-5 on 31 August and 1 September are shown in Appendix B.

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the distinct canopy coverage characteristics between the fertilized (I-5) and unfertilized (I-1) plots, with the latter exhibiting visible soil gaps and shadow patterns. These 72 images for three days were used for the extraction and calculation of VIs in visible remote sensing images of UAVs.

Histograms showing the red, green, and blue channels in remote sensing images with different solar elevation angles

The three-band (R, G, and B) histograms of the visible light images for plots I-1 and I-5 on 26 August are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. On 26 August, three peaks in the histogram for plot I-5 appeared at 18:26, and there were double peaks for the three bands at 20:23 (Fig. 7).

Changes in the mean and median R, G, and B bands of the UAV images at different solar elevation angles

For plots I-1 and I-5 the mean and median values for the R, G, and B at different solar elevation angles on 26 and 31 of August and 1 September 2023, are shown in Figs. 8, 9 and 10. On 26 August 2023, the average variation trends for the pixel values in the R, G, and B bands for plots I-1 and I-5 were essentially the same (Fig. 8). Similarly, the average pixel values for the R, G, and B bands from plots I-1 and I-5 on 31 August and 1 September were also essentially the same (Figs. 9 and 10). This is the main reason for the changing trend in the visible light VIs.

Effects of different solar elevation angles (flight time) on the visible light VIs

The effects of the solar elevation angle on the visible light VIs on 26 and 31 of August and 1 September were analyzed. The average results of the visible light VIs on 26 August 2023 are shown in Fig. 11. The average values of the visible light VIs for ExG, ExGR, NGRDI, VARI, GLI, IKAW, MGRVI, RGBVI, and NGBDI decreased first and then increased with the change in solar elevation angle. For these indices, the average value for plot I-5 was higher than that of plot I-1, whereas for the values of IKAW and NGBDI the average for plot I-5 was lower than that of plot I-1. ExR, ExB, RGRI, and GBRI showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the change in solar elevation angle. For plot I-1 the mean ExR and RGRI for the four indices was generally found to be higher than that of plot I-5, and the mean ExB and GBRI for plot I-5 were generally higher than those of plot I-1.

The average value for each visible light VIs on 31 August 2023 is shown in Fig. 12. On the same day, the average values of ExG, ExGR, NGRDI, VARI, GLI, IKAW, MGRVI, RGBVI, and NGBDI initially decreased and then increased. Similarly, the average values of I-5 were higher than those of I-1, whereas the values of IKAW and NGBDI were the opposite. ExR, ExB, RGRI, and GBRI showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the change in the solar elevation angle. Among these four indices, the mean ExR and RGRI for plot I-1 were generally higher than those for plot I-5, while the mean ExB and GBRI for plot I-5 were generally higher than those of plotI-1. The conclusions for the 26 August 2023 were the same.

The average value for each visible VIs on 1 September 2023 is shown on Fig. 13. On this day, ExG, ExGR, NGRDI, VARI, GLI, IKAW, MGRVI, RGBVI, NGBDI, and other indices first decreased and then increased, and the average values for plot I-5 were higher than those for plot I-1, except for IKAW and NGBDI. For ExR, ExB, RGRI, and GBRI, the trend first increased and then decreased. The mean ExR and RGRI values for plot I-1 were higher than those for plot I-5, whereas the opposite was true for ExB and GBRI. This is consistent with the conclusions drawn on 26 and 31 of August 2023. The visible light VIs have a significant correlation with the change in solar elevation angle, with some indices being positively correlated while others are negatively correlated.

Correlation between solar elevation angle and visible light VIs

To further understand the correlation between solar elevation angle and visible light VIs, a correlation analysis between solar elevation angle and visible light VIs was conducted. On 26 August 2023, each visible VIs was correlated with the solar elevation angle, as shown in Fig. 14. The solar elevation angle was positively correlated with the visible VIs of ExB, ExR, GBRI, and RGRI for plots I-1 and I-5, and negatively correlated with ExG, ExGR, GLI, MGRVI, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGBVI, and VARI. There is a negative correlation with IKAW for plot I-1 and a positive correlation with IKAW for plot I-5.

The correlation between the solar elevation angle and visible light VIs on 31 August 2023 is shown in Fig. 15. The solar elevation angle was positively correlated with ExB, ExR, GBRI, and RGRI for plots I-1 and I-5 and negatively correlated with ExG, ExGR, GLI, MGRVI, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGBVI, and VARI. There is a negative correlation with IKAW for plot I-1, while there was a positive correlation with IKAW for plot I-5.

The correlation between the solar elevation angle and visible light VIs on 1 September 2023 is shown on Fig. 16. The solar elevation angle on 1 September 2023 was positively correlated with ExB, ExR, GBRI, and RGRI for plots I-1 and I-5, and negatively correlated with ExG, ExGR, GLI, MGRVI, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGBVI, and VARI. Furthermore, plot I-1 was negatively correlated with IKAW, while there was a positive correlation for plot I-5. These results show that there is a correlation between the solar elevation angle and visible light VIs, but the specific correlation is also related to the type of visible light VIs.

According to the results for the 26 and 31of August and 1 September 2023, the solar elevation angle had a positive correlation with ExB, ExR, GBRI, and RGRI in regions with low and high growth levels and a negative correlation with ExG, ExGR, GLI, MGRVI, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGBVI, and VARI. Specifically, the solar elevation angle in the region with a high growth level was positively correlated with the effect of IKAW, whereas the solar elevation angle in the region with a low growth level was negatively correlated with IKAW.

Regardless of whether cotton growth is relatively strong or weak due to different nitrogen fertilizer application rates, with the increase in solar elevation angle, the ExR and RGRI for the cotton fields both showed significant increasing trends, while ExGR, ExG, RGBVI, MGRVI, GLI, NGRDI, and VARI showed significant decreasing trends (Table 3). Furthermore, there is no significant linear regression relationship between IKAW and the solar elevation angle. When cotton growth was relatively weak, the linear regression model of the visible light VIs (GBRI, ExB, and NGBDI) and the solar elevation angle of the cotton field were more likely to reach a significant level. From the slope in the table, the solar elevation angle was found to have the greatest influence on ExGR, followed by RGBVI and MGRVI, while IKAW had the smallest influence.

Range of the average visible light VIs at different solar elevation angles

To investigate the trends related to each exponential growth level, the average range of the mean values for each VIs under different solar elevation angles were calculated and the results shown in Figs. 17, 18 and 19.

The average range of the mean values for ExG, ExGR, GLI, ExB, RGBVI, NGBDI, and GBRI decreased with an increase in cotton growth (Figs. 17, 18 and 19.). This indicates that improved growth will reduce the influence of the solar elevation angle on these visible light VIs. The index with the largest mean range was ExGR, while GLI and ExB had the smallest ranges. The average range of the mean values for ExR, NGRDI, and MGRVI increased with the increase in cotton growth level, indicating that an improved growth level would increase the influence of the solar height angle, in which the average range of the mean values was the maximum MGRVI and minimum ExR. For VARI, IKAW, RGRI, and other visible light VIs, the influence rules were not consistent. It is possible that the growth level is not sensitive to the influence of some visible light VIs; however, other influencing factors cannot be excluded.

Discussion

Effects of the solar elevation angle on the visible light VIs

The results showed a positive correlation between solar elevation angle and ExB, ExR, GBRI, and RGRI, but there was no significant correlation with the cotton growth level, indicating that these visible light VIs are increased with an increase in solar elevation angle and had a negative correlation with ExG, ExGR, GLI, MGRVI, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGBVI, and VARI. Among the many factors that cause the change of VIs, the essence is that the change of pixel value leads to the change of VIs, and the change of solar elevation Angle leads to the change of pixel value and thus causes the change of VIs53. The magnitude of the solar elevation angle varies with the date, moment, latitude, and longitude54, and it can affect an object’s reflectance ρ(λ), which is calculated as follows:

Where L(λ) is the reflected light radiance at wavelength λ, θs is the solar elevation angle, and ES (λ) is the incident light radiance on the plane perpendicular to the sunlight.

Surface radiance, exo-atmospheric irradiance, and π are consistent for objects at the same location, and the reflectivity is only affected by the θS solar elevation angle (time). Yang33 showed that the NDVI decreased with an increase in the solar elevation angle (negative correlation). While Milton53 noted that the VIs at different latitudes were affected by the solar elevation angle. For example, NDVI, GNDVI, and NDRI, whereas the simple ratio index (SR) shows that the solar elevation angle has little influence. Hashimoto et al.55 showed that SR is most sensitive to solar elevation angles of 45° and 30°, and NDVI is the most reliable for solar radiation conditions. However, the use of high and low solar elevation angles should avoid the collection of UAV multi-spectral aerial images and have a greater impact on the reflectance of the canopy. When the solar elevation angle is small, dew may occur in the cotton field in the morning or evening, and this results in wet and dry vegetation having different reflectance values, which affects the visible light VIs56. In addition, when the solar elevation angle is low, the solar illumination intensity is also low, and the shadow area for vegetation is larger. When the solar elevation angle is high, the shadow area is smaller, and the presence of shadows leads to a reduction in vegetation reflectivity, which affects the extraction of the VIs57. For vegetation with good growth, the solar elevation angle was larger and the shadow area was smaller, while the opposite was true for weak vegetation. In addition, temperature influences the extraction of the VIs. When the temperature is low in the morning and evening, the leaf water content of plants may be higher and the leaves will spread out completely. While when the temperature is high at noon, the leaves will curl owing to water shortage, thus reducing the leaf area58 and this changes the reflectivity, thus affecting the VIs.

Ishihara59 found that the GRVI vegetation index decreases as the solar elevation angle increases, and this was confirmed on sunny days. The VIs at a small solar elevation angle, however, is not affected by growth conditions or diffuse reflected light, and this suggests that the value of NDVI should be obtained at a solar elevation angle of 30°. At this angle, the camera was always positioned vertically downward in the flight plan. If the camera angle is unchanged, a smaller solar elevation angle may lead to less reflected light entering the camera, and a shadow may be generated in the cotton field; the larger the solar elevation angle, however, the higher the relative reflectivity, which may produce a reliable visible light VIs. According to the bidirectional reflection distribution function (BRDF) effect60, the reflection from the surface of an object varies with changes in the incidence angle of the sunlight and the observation angle. The reflected light intensity obtained with an unchanged observation angle of the camera was proportional to the incident light intensity of the sun, and the incident light intensity of the surface of the object increased with an increase in solar elevation angle. However, in the flight plan for this study, the camera angle was always fixed. Therefore, the larger the solar elevation angle, the stronger the reflected light obtained by the camera, and the more reliable the results.

Some scholars believe that drone flights can be conducted between 14:00 and 16:00, without considering the exact flight time. However, we believe that even between 14:00 and 16:00, some visible light VIs showed large changes. The flight time of 14:00, 15:00, and 16:00 on August 26 were used as examples, and the solar elevation angles were found to be 1.04, 1.02, and 0.9, respectively. UAV aerial photography was carried out at these three moments, using the one-dimensional regression equation y = − 0.1756x + 0.191. The results showed that the ExGR values for plot I-1 were 0.009, 0.012, and 0.033, respectively. This indicates that from 14:00, the ExGR index value extracted by UAV aerial photography every hour (15:00 and 16:00) will increase by 33.3% and 266.7%, respectively, when compared with the value at 14:00. This is evidenced by the data even one hour before and after noon, owing to the different solar elevation angles. It will also cause the visible VIs, ExGR, of the UAV to change significantly.

The results of this study show that when the solar elevation angle is close to 60° (13:00–14:00), the average of each visible light VIs is relatively stable, whereas ExB, ExR, GBRI, RGRI, and other indices are positively correlated with the solar elevation angle. We speculate that such results may be related to the type of visible light VIs, although these indices are contrary to the above results. It is also suggested that to obtain reliable values, we should follow our existing results of aerial photography at high solar elevation angles to obtain the identified visible light VIs values.

Influence of growth level on the VIs

The results show that the influence of the growth level and visible light VIs has a strong correlation with the type of visible light VIs. The higher the growth level, the better the vegetation coverage. For example, the higher the growth level the greater the NDVI, as it has a strong correlation with green biomass. Moreover, SAVI and DVI were found to be significantly related to above-ground biomass61. The growth level directly affects the VIs. This is similar to our research results, but not all visible light VIs show such a phenomenon, as it depends on the correlation between the visible light VIs and biomass, and some visible light VIs have a strong correlation with biomass, while others have a weak correlation.

Numerous visible light VIs showed different changes under different crop growth levels, as some visible VIs was directly proportional to biomass, while others were inversely proportional. The better the growth level, the higher the vegetation coverage. For indices that are highly related to vegetation coverage, greater vegetation reflectivity was obtained by the drones. However, in areas with poor growth levels, these visible light VIs are affected by soil and water conditions, thereby diluting the average value62. Furthermore, the application scope differs for each visible light VIs. With different solar elevation angles, the growth levels had different effects with the visible light VIs, and this effect was not absolute as it was found to completely depend on the type of visible light VIs.

Conclusions

In this study, the effects of solar elevation angle and growth level under different nitrogen applications were evaluated for 13 visible light VIs obtained using UAV. Solar elevation angles vary depending on the flight time, while the height angle of the sun affects the VIs value of the visible light images of the UAVs, and the degree of influence is related to the category of the visible light VIs. (1) Regardless of whether the cotton growth was relatively strong or weak, with an increase in the solar elevation angle, ExR and RGRI in the cotton field showed a significant linear increasing trend, while ExGR, RGBVI, ExG, MGRVI, GLI, NGRDI, and VARI showed a significant linear decreasing trend, and there was no significant linear regression relationship between IKAW and the solar elevation angle. (2) With relatively weak cotton growth under no nitrogen application, the linear regression model for the visible light VIs (GBRI, ExB, NGBDI) and the solar elevation angle of the cotton field were both more likely to reach a significance level. (3) Under the condition of relatively prosperous cotton growth with nitrogen application, the influence of the solar elevation angle on ExG, ExGR, GLI, ExB, RGBVI, NGBDI, and GBRI can be reduced, and the influence on ExR, NGRDI, and MGRVI can be increased. (4) The solar elevation angle was found to have the largest influence on the ExGR, followed by the RGBVI, MGRVI, and IKAW. Consequently, when applying visible light VIs such as ExG, RGBVI and MGRVI to evaluate different cotton fields, it is advisable to maintain a consistent UAV flight time (solar elevation angle).

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript and further queries about sharing date can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Everitt, J. H. & Huaishun, C. Evaluation of grassland biomass using near-infrared and mid-infrared spectral parameters. Sichuan Grassland 1, 61–64 (1992).

Shihuang, Z., Gongbing, P. & Mei, H. Surface vegetation feature parameter inversion based on remote sensing and geographic information system. Climat. Environ. Res. 1, 80–91 (2004).

Wanxin, C. et al. Research on extraction method of desert shrub coverage based on UAV visible light data. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 28(6), 175–182+189 (2021).

Weiwei, Z. et al. Extraction of non-agricultural habitat in agricultural landscape based on visible light remote sensing images from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Ecol. Mag. 11–25, 1–17 (2023).

Roth, R. T. et al. Prediction of cereal rye cover crop biomass and nutrient accumulation using multi-temporal unmanned aerial vehicle based visible-spectrum vegetation indices. Remote Sens. 15(3), 580–580 (2023).

Guilherme, G. C. et al. Utilizing visible band vegetation indices from unmanned aerial vehicle images for maize phenotyping. Remote Sens. 16(16), 3015–3015 (2024).

Hammond, K. et al. Assessing within-field variation in alfalfa leaf area index using UAV visible vegetation indices. Agronomy 13(5), 1289 (2023).

Bendig, J. et al. Combining UAV-based plant height from crop surface models, visible, and near infrared vegetation indices for biomass monitoring in barley. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 39, 79–87 (2015).

Falco, N. et al. Influence of soil heterogeneity on soybean plant development and crop yield evaluated using time-series of UAV and ground-based geophysical imagery. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 7046 (2021).

Du, L. et al. Estimating leaf area index of maize using UAV-based digital imagery and machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15937 (2022).

Tom, D. S. et al. Applying RGB- and thermal-based vegetation indices from UAVs for high-throughput field phenotyping of drought tolerance in forage grasses. Remote Sens. 13(1), 147–147 (2021).

Guo, Z. et al. Biomass and vegetation coverage survey in the Mu Us sandy land-based on unmanned aerial vehicle RGB images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 94, 102239 (2021).

Bakacsy, L. et al. Drone-based identification and monitoring of two invasive alien plant species in open sand grasslands by six RGB vegetation indices. Drones 7(3), 207–207 (2023).

Torres-Sanchez, J., Lopez-Granados, F. & Pena, J. M. An automatic object-based method for optimal thresholding in UAV images: Application for vegetation detection in herbaceous crops. Comput. Electron. Agric. 114, 43–52 (2015).

Hasan, U., Sawut, M. & Chen, S. Estimating the leaf area index of winter wheat based on unmanned aerial vehicle RGB-image parameters. Sustainability 11(23), 6829 (2019).

Saberioon, M. M. et al. Assessment of rice leaf chlorophyll content using visible bands at different growth stages at both the leaf and canopy scale. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 32, 35–45 (2014).

Bassine, F. Z., Errami, A. & Khaldoun, M. Vegetation recognition based on UAV image color index. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2019 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Genova, Italy, 2019. IEEE 2019, 1–4 (2019).

Jiang, J. et al. Using digital cameras on an unmanned aerial vehicle to derive optimum color vegetation indices for leaf nitrogen concentration monitoring in winter wheat. Remote Sens. 11(22), 2667 (2019).

Yuefeng, L. et al. A novel desert vegetation extraction and shadow separation method based on visible light images from unmanned aerial vehicles. Sustainability 15(4), 2954–2954 (2023).

Jiale, J. et al. Estimation of the quantity of drip-irrigated cotton seedlings based on color and morphological features of UAV captured RGB images. Cotton J. 34(6), 508–522 (2022).

Announcement of the National Bureau of Statistics on Cotton Production in 2022. China Information News 2022–12–27(001).

Hong, C., Lei, Y. & Fenghua, Z. Effects of continuous cotton monocropping on soil physicochemical properties and nematode community in Xinjiang. China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 32(12), 4263–4271 (2021).

Yuting, W. Research on cotton growth parameter monitoring model based on UAV remote sensing images. 2023. Shandong University of Technology, MA thesis.

Hexuan, Z. & Aiwu, X. Analysis of cotton production status in Xinjiang. Cotton Process China 4, 4–7 (2020).

Maoguang, C. Evaluation of plastic film degradation and residue and cotton yield in cotton fields based on UAV images. 2023. Xinjiang Agricultural University, MA thesis.

Chen, Z. Study on rapid diagnosis method of cotton nitrogen based on UAV remote sensing. 2023. Xinjiang Agricultural University, MA thesis.

Nan, J. et al. Cotton growth parameter monitoring based on UAS visible light images and Convolutional neural networks. J Shihezi University 39(3), 282–288 (2021).

Huanbo, Y. Research on cotton yield inversion method based on visible light images of UAV. Shandong University of Technology, MA thesis (2021).

Yaping, L. et al. Monitoring leaf area index of cotton using UAV-acquired digital images. Chinese Agricultural Society Cotton Branch. China Cotton Mag. 1, 34346 (2018).

Zhuanchao, M. Research on retrieval method of cotton nitrogen and chlorophyll based on UAV visible light image. Shandong University of Technology, MA thesis (2022).

Jinli, X. Cotton seedling monitoring based on visible light image of UAV. Shihezi University, MA thesis (2020).

Brede, B. et al. Influence of solar zenith angle on the enhanced vegetation index of a Guyanese rainforest. Remote Sens. Lett. 6(12), 972–981 (2015).

Yang, L. et al. Influence of varying solar zenith angles on land surface phenology derived from vegetation indices: A case study in the Harvard forest. Remote Sens. 13(20), 4126–4126 (2021).

Jiang, R. et al. Assessing the operation parameters of a low-altitude UAV for the collection of NDVI values over a paddy rice field. Remote Sens. 12(11), 1850–1850 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. New method for cotton fractional vegetation cover extraction based on UAV RGB images. Int. J. Agric. Bil Eng. 15(4), 172–180 (2022).

Ning, W. et al. UAV-based remote sensing using visible and multispectral indices for the estimation of vegetation cover in an oasis of a desert. Ecol. Indic. 141, 109155 (2022).

Yiguang, F. et al. Estimation of the nitrogen content of potato plants based on morphological parameters and visible light vegetation indices. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1012070–1012070 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. Predicting grain yield in rice using multi-temporal vegetation indices from UAV-based multispectral and digital imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 130, 246–255 (2017).

Lopez-Garcia, P. et al. Assessment of vineyard water status by multispectral and RGB imagery obtained from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 72(4), 285–297 (2021).

Gerardo, R. & De Lima, I. P. Applying RGB-based vegetation indices obtained from UAS imagery for monitoring the rice crop at the field scale: A case study in Portugal. Agriculture 2023, 13 (1916).

Sebastian, V. et al. Understanding growth dynamics and yield prediction of sorghum using high temporal resolution UAV imagery time series and machine learning. Remote Sens. 13(9), 1763–1763 (2021).

Jie, J. et al. Use of digital camera mounted on a consumer-grade unmanned aerial vehicle to monitor the growth status of wheat. J. Nanjing Agricult. Univ. 42(04), 622–631 (2019).

Neto, J. C. A combined statistical-soft computing approach for classification and mapping weed species in minimum -tillage systems. The University of Nebraska Lincoln, (2004).

Hunt, E. R. et al. Evaluation of digital photography from model aircraft for remote sensing of crop biomass and nitrogen status. Precision Agricult. 6(4), 359–378 (2005).

Gitelson, A. A. et al. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 80(1), 76–87 (2002).

Louhaichi, M. et al. Spatially located platform and aerial photography for documentation of grazing impacts on wheat. Geocarto Int. 16(1), 65–70 (2001).

Wenhua, M.; Yiming, W.; Yueqing, W. Real-time detection of between-row weeds using machine vision. 2003 ASAE Annual Meeting. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (2003).

Kawashima, S. & Awashima, M. N. An algorithm for estimating chlorophyll content in leaves using a video camera. Ann. Bot. 81(1), 49–54 (1998).

Bareth, G. et al. Comparison of uncalibrated RGBVI with spectrometer-based NDVI derived from UAV sensing systems on field scale. Int. Arch. Photogram. Remote Sens. Spatial Inform. Sci. 8, 837–843 (2016).

Woebbecke, D. M. et al. Plant species identification, size, and enumeration using machine vision techniques on near-binary images. Opt. Agricult. For. 1836, 208–219 (1993).

Gamon, J. A. & Surfus, J. S. Assessing leaf pigment content and activity with a reflectometer. New Phytol. 143(1), 105–117 (1999).

Sellaro, R. et al. Cryptochrome as a sensor of the blue/green ratio of natural radiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154(1), 401–409 (2010).

Valencia-Ortiz, M. et al. Effect of the solar zenith angles at different latitudes on estimated crop vegetation indices. Drones 5(3), 80 (2021).

Wei, S. & Hongliang, F. Estimation of canopy clum** index from MISR and MODIS sensors using the normalized difference hotspot and darkspot (NDHD) method: The influence of BRDF models and solar zenith angle. Remote Sens. Environ. 187, 476–491 (2016).

Hashimoto, N. et al. Simulation of reflectance and vegetation indices for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) monitoring of paddy fields. Remote Sens. 11(18), 2119 (2019).

Zhang, F. & Zhou, G. Estimation of vegetation water content using hyperspectral vegetation indices: A comparison of crop water indicators in response to water stress treatments for summer maize. BMC Ecol. 19(1), 18 (2019).

Ying, Z. et al. Extracting methods for forestry and grass coverage based on UAV visible light data and multispectral data. China Soil Water Conserv. Sci. 21(5), 120–128 (2023).

Shuangtao, X. Effects of high temperature on biological and physiological characteristics of cotton. Shihezi University, MA thesis (2018).

Ishihara, M. et al. The impact of sunlight conditions on the consistency of vegetation indices in croplands—effective usage of vegetation indices from continuous ground-based spectral measurements. Remote Sens. 7(10), 14079–14098 (2015).

Kuusk, A. The hot spot effect in plant canopy reflectance. Photon-vegetation interactions: Applications in optical remote sensing and plant ecology 139–159 (Springer, 1991).

Salman, A. K.; Wheib. K. A. The relationship between the above-ground biomass and the vegetation cover indices at different salinity levels. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1158 (2). (2023).

Burns, B. W. et al. Determining nitrogen deficiencies for maize using various remote sensing indices. Precision Agricult. 23(3), 1–21 (2022).

Funding

This project received funding from the Key Research and Development Program Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (2022B02053-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. completed all relevant tests and formal identification of plant materials. The material is not stored in the public herbarium.J.L. M.Y. Y.T. and G.A. completed all the model analysis, J.L. and W.W. participated in the drawing up of the manuscript, designed the experment, and wrote the frist draft of the manuscript.J.Z. supervised the research and reviewed the manuscript.X.B. and H.D. depicted and discussed. L.D. and C.Z participated in mechanism discussions and provided language editing.All authors have red and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Statement

The site of this experiment is in the Alar Experimental Station of Cotton Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The cotton crop tested is Tahe No. 2, which is held by Xinjiang Tarim Seed Co., LTD., and the variety source is 07–49×K531. Permission to collect cotton has been obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wu, W., Zhao, C. et al. Effects of solar elevation angle on the visible light vegetation index of a cotton field when extracted from the UAV. Sci Rep 15, 18497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00992-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00992-6